Strategic Management

Anuncio

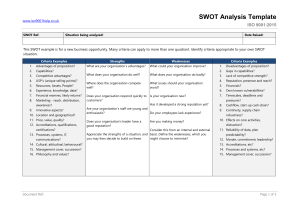

What is strategic planning? Defining such term is not an easy task, nor is the action which it involves, but most organisations are aware of its importance. So what is strategic planning? Most definitions given to it provide a good understanding of what it involves, and since there is always a favourite to everything, I have chosen the one given by the Oxford Pocket Dictionary, a very simple, yet self explanatory definition: STRATEGY: The art of war, specially planning of movements of troops and ships etc. into favourable positions; plan of action or policy in business or politics etc. Running a business is an everyday battle, and just like no good military officer would undertake even a small scale attack on a limited objective without a clear understanding of his strategy, no business manager (or management board) would ever tackle a new venture without first deciding on what it is to be done in order to be successful, i.e. without planning a strategy. However, this is seldom the case, as in the business management field it is often seen men deploying resources on a large scale without any clear understanding of what their strategy is. So what differentiates a successful strategy from a bad one? Or in other words: What are the Strengths and Limitations of Strategic Managent? J.C. Craig in his book Strategic Management proposes the following four points for a successful strategy: • Long term, simple goals, i.e. do we have a clear understanding of what we are aiming for? • Thorough analysis of the competitive environment, i.e. have we identified and analysed the needs which are common to the consumers of our sector across society? • Objective appraisal of resources, i.e. have we recognised our key resources and capabilities? • Effective implementation, i.e. the most brilliant strategy is useless if it is not implemented effectively. The literature suggesting successful criteria for a useful strategy is extensive, if not infinite. Different schools suggest different theories, and over the years there have been some changes in the way strategic planners think. The reason for this is obvious: the rules are different and always changing. Technology, for instance, is changing the way companies approach their work, and decentralised organisational structures are affecting managerial decisions more and more every day. Perhaps it would be too premature to conclude this work at the stage of its introduction, but I do not believe strategies can be bad for organisations − it is their planning and implementation what can cause the detrimental effects often observed. Strategies may not always produce the expected results. However, even the worst of all strategies will teach something new. We all learn from our mistakes, and by analysing some of these [mistakes] we can stand up again and try and correct them. Sure the second time we will take more time and effort to develop our plan, and implement our strategy. In this essay I plan to give an outline of some of the most common mistakes organisations have made when involved in the task of strategic planning. I analyse each of the criteria for success J.C. Craig has given in his text Strategic Management. Common pitfalls of strategic planning. 1. Long−term, simple goals: Seymour Tilles in his paper How to Evaluate Corporate Strategy defines the first problem in a very neat way: Goals give an indication on what the company is trying to achieve and to become. Both parts are equally important for a full understanding of the company's objectives. Achieving. What a company wishes to do with respect to its environment. It would be impossible to define 1 this with one sentence. This is specially true for managers who perceive that their firm is not only part of the market but also of an industry, the community, the economy, and other systems. In each case there are unique relationships to observe (e.g. with competitors, municipal leaders, Congress and so on) (Tilles, 1963). Indeed, thinking strategically requires a fresh and open perspective of the world. Becoming. If one asks a child what he/she would like to accomplish when they grow up, answers will fall into two distinct categories: Those who hope to have (e.g. loads of cash) and those who hope to be, i.e. the ones with a clear idea of where they are going. It is the same with many companies: Most strategic plans are no more than financial hopes filled with nice numbers. These hopes then turn into inexorable demands that operating managers feel compelled to attain at any cost (Paul, 1978). Moreover, there is the growth fad. What happens when a manager sees the company's future in a very similar way as a child's view of himself? Most reply bigger when asked what they want their companies to become over the next few years, without realising that bigger is not a synonym of profitable. Indeed, bigger is not always better. A company which is at present highly profitable may grow into bankruptcy if it tries to increase its sales growth, rather than seeking survival in say, cost reduction. Having said this, let's accept it. The most common goal of most companies is to increase in profitability, now and in the future. So what goes wrong when management sets optimistic goals for an organisation? The answer relies on the creation of flawed assumptions, i.e. having the right strategy for the wrong problem. If the managers' predictions are not realistic, the result may be highly detrimental for the company. The best laid strategies go awry when management fails to chart the realities of the business situation − when one or more of management's assumptions, premises or beliefs are incorrect, or when internal inconsistencies among them render the overall `theory of the business' no longer valid (Picken, 1998). Gary Hamel and C.K. Prahalad, in their book Competing for the Future explain this theory by explaining how every manager has his own set of biases and assumptions about the structure of their own industry, about how to make money in such industry, about who they are competing against and who the customers are and aren't, and so on Even more worrying is the fact that over time, this set of management's beliefs and assumptions about the organisation and its industry, become broadly shared among the individuals which form the organisation. Adding to this, many organisations now look for people with similar education backgrounds, put them through the same indoctrination and teach them the set of rules they believe are best for survival in that particular industry. This phenomenon is given the name of `the Dominant Logic of an organisation', and it is a clear strategic trap. As Hamel and Prahalad state, any company that defines itself solely in terms of its current industry may well miss opportunities created by technologies or market forces that will ultimately replace or redefine the current segment, in other words, having a narrow−minded perspective will tie a company's fate to that of its particular market. Dominant logic is linked, in most cases, with manager's mental representations of the world based on historical information rather than on expectations about the future. It is also grouped with blind spots in competitor analysis, but these are part of the analysis of the second criteria, i.e. the thorough analysis of the competitive environment. The take−home−message is: Have a clear understanding of what the company is aiming for is a crucial step in the process of strategic planning. Management has to be careful with the development of plans based on flawed assumptions and have a clear vision of what it wants to achieve. The next step is to analyse the external environment, i.e. is the mission we have just proposed feasible considering the environment around us? 2. Thorough analysis of the competitive environment Michael Porter of Harvard Graduate School of Business, in his paper What is Strategy?, says that in any 2 industry, whether it is domestic or international or produces a product or a service, the rules of competition are embodied in five competitive forces: the entry of new competitors, the bargaining power of buyers, the bargaining power of suppliers, the threat of substitutes, and the rivalry among the existing suppliers (See figure 1 below). Figure 1. The five competitive Forces that determine industry profitability. When management fails to evaluate or recognize the implications of events and changing conditions in the competitive environment, even the best mission can collapse before it is even implemented. The concept of `blind spots' in competitor analysis has called researcher's attention: organisations frequently misjudge the boundaries of their industries, do poorly in identifying who their competitors are, and make erroneous assumptions about them. It can be even worse when strategic `planners' anticipate competitors' moves based on their past behaviour, rather than interpreting their true strategic intentions. In other words, they think competitors will follow historical patterns of behaviour, and/or think in a very similar strategic way. Analysing the environment using the five forces framework is not an easy task. However, it is one of strategic management pros, since it allows a firm to see through the complexity and pinpoint those factors that are critical to competition in its industry, as well as to identify those strategic innovations that would most improve the industry's and it's own profitability. Illustrating these forces is not part of this essay, but I feel obliged to at least, give a short description of each. Suppliers: Raw materials, labour, machinery and capital are necessary inputs to a firm's production process. However, these are supplied by various interest groups within the industry. The strength of these suppliers can significantly affect an industry's potential profit, if they can exert a major influence on firms for their goods and services. Buyers: Powerful customers can also exert a competitive influence over suppliers and can bargain away any potential profits from the firms in the industry. Moreover, if the number of buyers for the outputs of an industry are small, they can affect the profit that can be derived. New entrants: They bring new production capacity, the desire to establish a secure place in the market, and sometimes substantial resources with which to compete. As a new organisation enters the market, they have the potential to extract the profit unless the demand grows faster than new entrants to a market. Substitution: It represents the buyer's propensity to substitute one firm's product for another product. The strength of competition from substitutes is affected by the ease with which buyer can change over the substitute. If the substitute becomes more attractive in terms of price, performance or both, then some buyers will be tempted to move their custom to a competing firm. Substitution can also represent an offensive opportunity for a firm to increase its own market by offering its products as substitutes to another buyer. Rivalry among competitors: Market growth and number of competing firms in the industry are just some of the factors which effect rivalry among competitors. Each firm can employ its own style of competitive strategy in an effort to jockey for better position and gain competitive edge. Offering something that competitors cannot duplicate easily or cheaply gives a firm not only market edge but also a unique competitive capability. At this point through the analysis, it is difficult to see why the above model − Porter's Five Forces Model− would be bad for an organisation. However, the quality of strategic management decisions is not only dependent on this model, but also, to a large extent, on how valid and reliable is the understanding by an organisation of its internal environment, including its trends. This is the subject of the third point in my discussion. 3 3. Objective appraisal of resources: Understanding the environment is all very well, but knowing what differentiates one company from another is what really shows why some firms consistently outperform others within the same industry. The key differences between firms are in resources and capabilities, i.e. its tools and personality. As J.C. Craig points out: one consequence of the recent emphasis on resources has been to redirect the firm's attention to what it is truly capable of supplying. In addition to giving a realistic point of view to the firm, the resource based sight has other values. When, for instance, the firms' market environment is subject to a rapid change, then a strategy based on resources and capabilities may provide a more stable, long−term focus. Last but not least, the fact that profits are a return on the resources owned by a firm. Once there is a good understanding by an organisation of its external and internal environment, a SWOT analysis can be used in the preliminary stage of strategic decision making. SWOT provides the basic framework for strategic analysis. It generates lists, or inventories, of Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats. Adam J. Koch, of the Faculty of the School of Business, University of Technology, Hawthorn, Victoria, Australia, argues on the validity and reliability of this tool of strategic analysis. He says that it is often the poor quality of input and inadequate skills of those who use SWOT, rather than the properties of this tool, that are to blame for most cases of its less than successful implementation. His two basic criticisms of the SWOT usage are as follows: On the one hand, most of the reported usage of SWOT accounts for no more than a poorly structured, very general, hastily conducted exercise that produces unverified, vague and inconsistent inventories of factors regarded by the proposing individuals as most important components of their organisation's strategic situation. On the other hand, Mintzberg (1994) suggests that SWOT is the main cause of what is considered an excessive formalisation of the strategy making process. While it is true that many organisations develop an excessively formalised approach to strategic management, the blame for this over−formalisation should be laid on those who misconceive the role of this tool, misapply it, or substantially misinterpret SWOT results. As I said earlier, there are various schools of strategic thinking, and Adam J. Koch, based in these two misconceptions, has his own where he proposes a corresponding model of this analytical process in order to help organisations enhance their SWOT analysis. I believe it is enough for the purpose of this essay to outline the limitations he proposes, and to focus now on the limitations of the final stage of strategic management: The implementation of the plan. 4. Effective implementation of a strategy: The most brilliant strategy is useless unless it is implemented effectively (J.C. Craig). For an implementation to be effective, certain criteria must be met: There must be an establishment of the leadership, an organisational structure and management systems which induce the commitment and co−ordination of employees, and the effective mobilisation of resources to fulfil such strategy. Note however that all this goes in accordance with all of the above points, i.e. a flawed strategy, no matter how good the leadership is, no matter how clear the goal, is doomed to failure. Managing a strategy is clearly a serious problem, one that should not be taken lightly. It is often the case that the same management that creates the plan ends up with the responsibility for accomplishing its financial goals without any control over the events on which the plan is based (Paul et al, 1978). Management may also spend too much time talking about say, how the off−site meeting facilitated team building. They document the plan by going to the expense of publishing and distributing it, but with no explanation about how the plan was derived, who is accountable, or what it means to the firm's future. Another serious problem about implementing a strategy is to consider such task as an event, and not a process. A strategy has to be evaluated constantly. The ever changing environment may affect the way the plan is 4 implemented and a review of the goals has to be considered. This allows me to conclude this essay by asking the question Is strategic planning a bad thing then? If we review strategic planning from a scientific perspective, it is not possible to say whether strategic planning has helped organisations that have adopted it, because nobody knows what kind of decisions would have been made without strategic planning. It is true however, that there is a growing list of companies that have become entangled in financial misfortunes after following decisions made in accordance with the principles of strategic planning. Surely they, and the companies around them, have learnt valuable lessons from it. Nevertheless, it would be difficult to say that strategic planning is a bad thing: the sole analysis made of the external environment and internal resources and capabilities benefits the company by providing a perspective not seen without it. The take−home message is that a sound strategy, implemented without error, is far more likely to come home a winner than the most brilliant and innovative of strategies, poorly implemented. Bibliography: • Strategic Management (1993). Craig, J.C. and Grant R.M. Kogan−Page. • How to evaluate corporate strategy. Tylles, S. Harvard Business Review, July/August 1963. • SWOT does not need to be recalled: It needs to be enhanced. Koch, A.J. (akoch@swin.edu.au) • The reality gap in Strategic planning. Paul, R.N. et al. Harvard Business Review, May/June 1978. • Right StrategyWrong Problem. Picken, J.C. and Dess, G.G. Organizational Dynamics, 1998 v27 n1 p35(15). • Competing for the Future. Hamel, G. and Prahalad, C.K. (Boston, Harvard University School Press, 1994). • What is Strategy? Porter, M. Harvard Business Review, November/December 1996. • The rise and fall of strategic planning. 1994. Prentice Hall. Hemel. Hempstead. Buyers Potential Entrants Substitutes 5 Suppliers Industry Competitors Threat of new entrants Threat of Substitutes Bargaining Power of Buyers Bargaining Power of Suppliers 6