1-s2.0-S1936879817306453-main

Anuncio

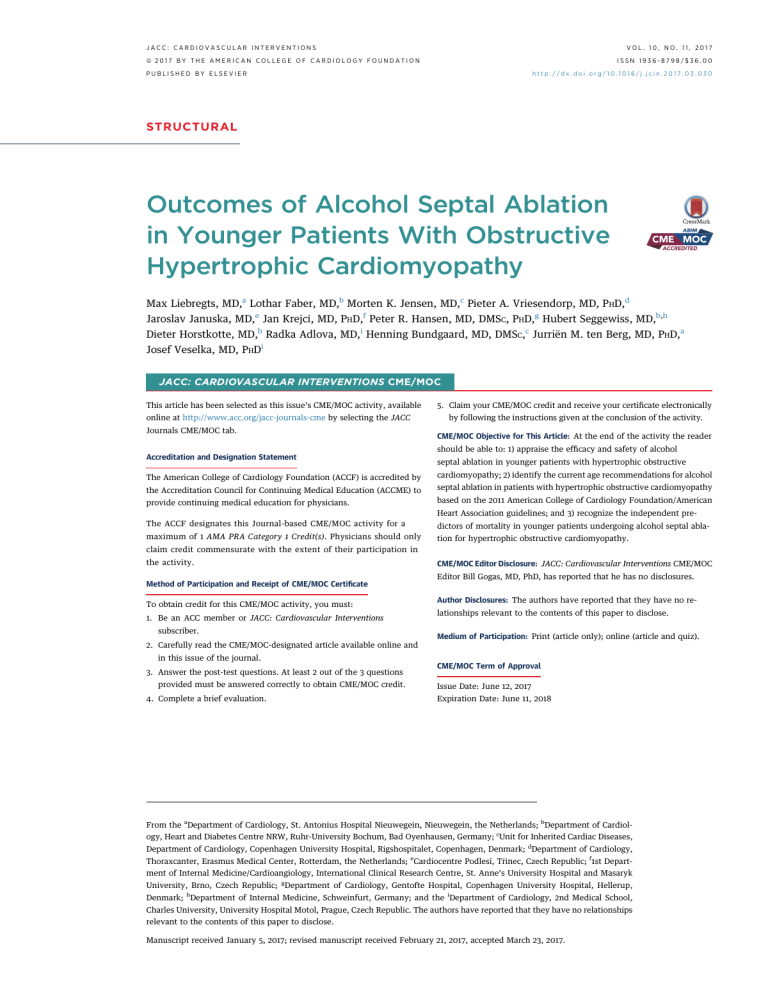

JACC: CARDIOVASCULAR INTERVENTIONS VOL. 10, NO. 11, 2017 ª 2017 BY THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY FOUNDATION ISSN 1936-8798/$36.00 PUBLISHED BY ELSEVIER http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2017.03.030 STRUCTURAL Outcomes of Alcohol Septal Ablation in Younger Patients With Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Max Liebregts, MD,a Lothar Faber, MD,b Morten K. Jensen, MD,c Pieter A. Vriesendorp, MD, PHD,d Jaroslav Januska, MD,e Jan Krejci, MD, PHD,f Peter R. Hansen, MD, DMSC, PHD,g Hubert Seggewiss, MD,b,h Dieter Horstkotte, MD,b Radka Adlova, MD,i Henning Bundgaard, MD, DMSC,c Jurriën M. ten Berg, MD, PHD,a Josef Veselka, MD, PHDi JACC: CARDIOVASCULAR INTERVENTIONS CME/MOC This article has been selected as this issue’s CME/MOC activity, available online at http://www.acc.org/jacc-journals-cme by selecting the JACC Journals CME/MOC tab. 5. Claim your CME/MOC credit and receive your certificate electronically by following the instructions given at the conclusion of the activity. CME/MOC Objective for This Article: At the end of the activity the reader should be able to: 1) appraise the efficacy and safety of alcohol Accreditation and Designation Statement septal ablation in younger patients with hypertrophic obstructive The American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF) is accredited by cardiomyopathy; 2) identify the current age recommendations for alcohol the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) to septal ablation in patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy provide continuing medical education for physicians. based on the 2011 American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association guidelines; and 3) recognize the independent pre- The ACCF designates this Journal-based CME/MOC activity for a dictors of mortality in younger patients undergoing alcohol septal abla- maximum of 1 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s). Physicians should only tion for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. claim credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity. Method of Participation and Receipt of CME/MOC Certificate To obtain credit for this CME/MOC activity, you must: 1. Be an ACC member or JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions subscriber. CME/MOC Editor Disclosure: JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions CME/MOC Editor Bill Gogas, MD, PhD, has reported that he has no disclosures. Author Disclosures: The authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose. Medium of Participation: Print (article only); online (article and quiz). 2. Carefully read the CME/MOC-designated article available online and in this issue of the journal. 3. Answer the post-test questions. At least 2 out of the 3 questions provided must be answered correctly to obtain CME/MOC credit. 4. Complete a brief evaluation. CME/MOC Term of Approval Issue Date: June 12, 2017 Expiration Date: June 11, 2018 From the aDepartment of Cardiology, St. Antonius Hospital Nieuwegein, Nieuwegein, the Netherlands; bDepartment of Cardiology, Heart and Diabetes Centre NRW, Ruhr-University Bochum, Bad Oyenhausen, Germany; cUnit for Inherited Cardiac Diseases, Department of Cardiology, Copenhagen University Hospital, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark; dDepartment of Cardiology, Thoraxcanter, Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands; eCardiocentre Podlesí, Trinec, Czech Republic; f1st Department of Internal Medicine/Cardioangiology, International Clinical Research Centre, St. Anne’s University Hospital and Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic; gDepartment of Cardiology, Gentofte Hospital, Copenhagen University Hospital, Hellerup, Denmark; hDepartment of Internal Medicine, Schweinfurt, Germany; and the iDepartment of Cardiology, 2nd Medical School, Charles University, University Hospital Motol, Prague, Czech Republic. The authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose. Manuscript received January 5, 2017; revised manuscript received February 21, 2017, accepted March 23, 2017. Liebregts et al. JACC: CARDIOVASCULAR INTERVENTIONS VOL. 10, NO. 11, 2017 JUNE 12, 2017:1134–43 Age-Specific Outcomes of ASA for Obstructive HCM Outcomes of Alcohol Septal Ablation in Younger Patients With Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Max Liebregts, MD,a Lothar Faber, MD,b Morten K. Jensen, MD,c Pieter A. Vriesendorp, MD, PHD,d Jaroslav Januska, MD,e Jan Krejci, MD, PHD,f Peter R. Hansen, MD, DMSC, PHD,g Hubert Seggewiss, MD,b,,h Dieter Horstkotte, MD,b Radka Adlova, MD,i Henning Bundgaard, MD, DMSC,c Jurriën M. ten Berg, MD, PHD,a Josef Veselka, MD, PHDi ABSTRACT OBJECTIVES The aim of this study was to describe the safety and outcomes of alcohol septal ablation (ASA) in younger patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. BACKGROUND The American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association guidelines reserve ASA for older patients and patients with serious comorbidities. Data on long-term age-specific outcomes after ASA are scarce. METHODS A total of 1,197 patients (mean age 58 14 years) underwent ASA for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Patients were divided into young (#50 years), middle-age (51 to 64 years), and older ($65 years) groups. RESULTS Thirty-day mortality and pacemaker implantation rates were lower in young compared with older patients (0.3% vs. 2% [p ¼ 0.03] and 8% vs. 16% [p < 0.001], respectively). Ninety-five percent of young patients were in New York Heart Association functional class I or II at last follow-up. During a mean follow-up period of 5.4 4.2 years, 165 patients (14%) died. Annual mortality rates of young, middle-age, and older patients were 1%, 2%, and 5%, respectively (p < 0.01). Annual adverse arrhythmic event rates were similar in the 3 age groups at about 1% (p ¼ 0.90). Independent predictors of mortality in young patients were age, female sex, and residual left ventricular outflow tract gradient. Additionally, young patients treated with $2.5 ml alcohol had a higher all-cause mortality rate (0.6% vs. 1.4% per year in patients treated with <2.5 ml, p ¼ 0.03). CONCLUSIONS ASA in younger patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy was safe and effective for relief of symptoms at long-term follow-up. The authors propose that the indication for ASA can be broadened to younger patients. (J Am Coll Cardiol Intv 2017;10:1134–43) © 2017 by the American College of Cardiology Foundation. A lcohol septal ablation (ASA) for the treatment A recent smaller study (n ¼ 217) showed that ASA in of obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients #55 years of age was effective for reduction (HCM) was introduced in 1995 as a percuta- of symptoms at short-term follow-up and had low neous alternative to surgical myectomy (1). The mortality and adverse arrhythmic event (AAE) rates American College of Cardiology Foundation/Amer- at long-term follow-up, comparable with patients ican Heart Association guidelines on HCM state that with nonobstructive HCM (7). The aim of the present ASA should be reserved for older patients and pa- study was to further assess if ASA is safe and effective tients with serious comorbidities and give a Class III for younger patients by comparing complication recommendation (Level of Evidence: C) for ASA in rates, treatment effects, and long-term outcome of younger patients if myectomy is a viable option (2). young, middle-age, and older patients after ASA. These recommendations reflected the lack of ASA studies with long-term follow-up, whereas myectomy METHODS had already been proved to be safe and effective. As a result, most studies comparing long-term outcomes STUDY DESIGN AND PATIENT POPULATION. An in- of ASA and myectomy have significant age differ- ternational multicenter observational cohort design ences (3–5). Thus, in a recent meta-analysis of long- was used. The study population consisted of 1,197 term outcomes following septal reduction therapy, consecutive patients with HCM (mean age 58 14 the ASA patients (n ¼ 2,013) were 9 years older than years; range 13 to 88 years; 49% female) who under- the myectomy patients (n ¼ 2,791) (6). Studies on went ASA because of highly symptomatic left ven- long-term outcome of young ASA patients are scarce. tricular outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction despite 1135 1136 Liebregts et al. JACC: CARDIOVASCULAR INTERVENTIONS VOL. 10, NO. 11, 2017 JUNE 12, 2017:1134–43 Age-Specific Outcomes of ASA for Obstructive HCM ABBREVIATIONS optimal medical therapy. Procedures were AND ACRONYMS performed at 7 tertiary invasive centers from sex-, and country-specific mortality rates obtained 4 European countries (Germany–Bad Oyen- from the respective national registries (http://www. hausen; Czech Republic–Prague, Trinec, and destatis.de [Germany]; http://www.czso.cz [Czech Brno; Republic]; http://www.cbs.nl [the Netherlands]; http:// AAE = adverse arrhythmic event ASA = alcohol septal ablation CI = confidence interval HCM = hypertrophic cardiomyopathy HR = hazard ratio the Netherlands–Nieuwegein; Denmark–Copenhagen and Gentofte) compared with the general population using age-, be- www.dst.dk [Denmark]). Because of the controversy tween January 1996 and August 2015. Studies regarding the use of ASA in very young patients, the reporting outcomes of subsets of this cohort subgroup #35 years of age was also subjected to a have been published before (8–11). separate descriptive analysis. FOLLOW-UP AND ENDPOINTS. Follow-up started at the ICD = implantable SEE PAGE 1144 time of ASA. There were some differences in post-ASA cardioverter-defibrillator Patients met the criteria for invasive treat- LVOT = left ventricular outflow tract ment, NYHA = New York Heart including: 1) ventricular septal thickness $15 mm; 2) (provocable) LVOT Association SCD = sudden cardiac death VT = ventricular tachycardia gradient $50 mm Hg; and 3) persistent New follow-up among the centers. Conventionally, all patients had first clinical checkups 3 to 6 months after the procedure and annual routine checkups after that. Adverse events were retrieved from national patient York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class registries, from hospital patient records at the center at III or IV dyspnea or Canadian Cardiovascular which follow-up occurred, and from information Society class III or IV angina (2,12). In exceptional cases, provided patients with documented exertional syncope were general practitioners. All implantable cardioverter- by patients themselves and/or their also included. The choice of ASA instead of surgical defibrillator (ICD) shocks were evaluated by an myectomy was based on patient profile (age, comor- experienced electrophysiologist, unaware and inde- bidities, and so on) and patient preference. All patients pendent of the study purpose and endpoints. gave informed consent before the procedure. Details of The primary endpoints of this study were all-cause the ASA technique have been published before (1,10). mortality and AAEs during long-term follow-up. AAEs All procedures were performed by experienced inter- consisted of sudden cardiac death (SCD), resuscitated ventional cardiologists and guided by myocardial cardiac arrest due to ventricular fibrillation or ven- contrast echocardiography. tricular tachycardia (VT), and appropriate ICD Patients were divided into 3 age groups: young shock, respectively. Secondary endpoints were peri- (#50 years), middle-age (51 to 64 years), and older procedural (#30 days) atrioventricular block, cardiac ($65 years). Survival rates in the 3 groups were tamponade, AAEs and mortality; pacemaker implantation, ICD implantation, (provocable) LVOT gradient, NYHA functional class, and need for reintervention at last clinical checkup, respectively. The study was in T A B L E 1 Baseline Characteristics of 1,197 Patients Before compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Alcohol Septal Ablation STATISTICAL ANALYSIS. SPSS version 24 (IBM, #50 Years (n ¼ 369) 51–64 Years (n ¼ 423) $65 Years (n ¼ 405) Armonk, New York), R version 3.1.1 (R Foundation for 41.7 7.5 58.4 4.1† 72.6 5.0† soft Excel 2010 (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington) 114 (31) 190 (45)† 280 (69)† were used for all statistical analyses. Categorical 293 (80) 352 (83) 363 (90)† CCS class $III 79 (22) 95 (23) 78 (19) LVEF (%) 71 9 70 10 69 10* Left atrial diameter (mm) 47 7 46 7 47 7 SD and skewed data as median (interquartile range). LVEDD (mm) 43 6 44 6 43 7 To Basal septal thickness (mm) 21 5 20 4† 20 3† t test or Mann-Whitney U test was used, and to compare categorical variables, the chi-square test Age (yrs) Female NYHA functional class $III 110 39 111 44 121 47† Syncope 92 (25) 85 (20) 81 (20) $2 RFs 57 (22) 31 (12) 11 (5)† Pacemaker 14 (4) 17 (4) 16 (4) ICD 31 (8) 12 (3)* 4 (1)† LVOT gradient (mm Hg) Values are mean SD or n (%). *p < 0.01. †p < 0.001 compared with patients #50 years of age. CCS ¼ Canadian Cardiovascular Society; ICD ¼ implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; LVEDD ¼ left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LVEF ¼ left ventricular ejection fraction; LVOT ¼ left ventricular outflow tract; NYHA ¼ New York Heart Association; RF ¼ conventional risk factor for sudden cardiac death. Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), and Micro- variables are summarized as percentages. Normally distributed continuous data are expressed as mean compare continuous variables, the Student was used. Cox proportional hazard regression was used to identify predictors of all-cause mortality and AAEs during long-term (>30 days) follow-up. The following variables with a potential impact on primary endpoint rates were evaluated, first in a univariate model: age, sex, baseline and residual NYHA functional class, baseline and residual LVOT gradient, conventional risk factors for SCD (family history of SCD, history of Liebregts et al. JACC: CARDIOVASCULAR INTERVENTIONS VOL. 10, NO. 11, 2017 JUNE 12, 2017:1134–43 Age-Specific Outcomes of ASA for Obstructive HCM unexplained syncope, maximum left ventricular wall thickness $30 mm, nonsustained VT on Holter F I G U R E 1 Distribution of Age at Alcohol Septal Ablation in 82 Very Young, 369 Young, 423 Middle-Age, and 405 Older Patients monitoring, abnormal blood pressure response to exercise), volume of alcohol injected during ASA, and need for reintervention. Variables with p values <0.15 were then entered into a multivariate analysis, which was performed using backward stepwise multiple Cox regression. Predictors of the primary endpoints are expressed as hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Kaplan-Meier graphs were used to show survival rates, and differences in survival were assessed using the log-rank test. All tests were 2 sided, and p values <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. RESULTS CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS. The baseline charac- teristics of the young (n ¼ 369, mean age 42 8 Blue ¼ very young; green ¼ young; purple ¼ middle age; red ¼ older. ASA ¼ alcohol septal ablation. years), middle-age (n ¼ 423, mean age 58 4 years), and older (n ¼ 405, mean age 73 5 years) patients are shown in Table 1. Figure 1 depicts the distribution kinase-MB of age at ASA within the different age groups. More kinase-MB 77 IU/l vs. 82 IU/l, respectively, p < 0.01). older patients were in NYHA functional class III or IV Complete (transient) atrioventricular block occurred before ASA compared with young patients (90% vs. in 32% of patients #50 years, compared with 42% of 80%, p < 0.001). More young patients had at least 2 patients $65 years (p < 0.01), resulting in permanent conventional risk factors for SCD (22% vs. 5% of pacemaker implantation after ASA in 8% and 16%, older patients, p < 0.001), and more young patients respectively (p < 0.001), at last follow-up visit. had ICDs implanted (8% vs. 1% of older patients, p < 0.001). In 456 patients (38%), <60% of the conventional risk factors for SCD were available. These patients were therefore considered not to be risk stratified at all. During the study period, 210 patients were sent primarily to surgical myectomy. measurements TREATMENT (maximum EFFECTS. Long-term creatinine outcomes are shown in Table 3. At last checkup, 95% of the young patients were in NYHA functional class I or II, compared with 81% of the older patients (p < 0.001). Likewise, 89% of the young patients had improved at least 1 NYHA functional class, compared with 80% of PROCEDURAL OUTCOMES. Periprocedural (#30 days) older patients (p < 0.001). Residual LVOT gradient, outcomes in the 3 age groups are shown in Table 2. reduction in LVOT gradient, and number of Periprocedural mortality was higher in older patients compared with younger patients (2% vs. 0.3%, p ¼ 0.03), and the incidence of AAEs was similar T A B L E 2 Periprocedural (#30 Days) Outcomes of 1,197 Patients (p ¼ 0.45). The AAEs within the first month all Following Alcohol Septal Ablation occurred in-hospital: 2 patients died of ventricular #50 Years (n ¼ 369) fibrillation (day 2 in a 42-year-old man, day 9 in an 86-year-old woman), and 22 patients received suc- Alcohol (ml) cessful electric cardioversion for VT or ventricular Maximum CK-MB (IU/l) fibrillation (16 within 48 h and 2 on the 2nd, 4th, and Complete heart block 10th days, respectively). Cardiac tamponade complicated the procedure in 3% of the older patients, compared with 0.3% of the young patients (p < 0.01). All cases of cardiac tamponade were thought to be related to temporary pacing. In young patients, more alcohol was used, compared with older patients (mean 2.4 ml vs. 2.1 ml, p < 0.01), which did not result in larger infarcts as assessed by creatinine $65 Years (n ¼ 405) 51–64 Years (n ¼ 423) 2.0 (2.0-3.0) 2.0 (1.5-2.5)‡ 2.0 (1.5-2.5)‡ 77 (52-127) 73 (54-140) 82 (55-164)* 119 (32) 161 (39) 169 (42)† Cardiac tamponade 1 (0.3) 2 (0.5) 12 (3.0)† AAE 7 (1.9) 6 (1.4) 11 (2.7) Mortality 1 (0.3) 2 (0.5) 8 (2.0)* Values are median (interquartile range) or n (%). Maximum CK-MB activity concentration was available in 72% of patients, whereas CK-MB mass concentration measurements obtained in patients from the Czech Republic were excluded from the analysis. *p < 0.05. †p < 0.01. ‡p < 0.001 compared with patients #50 years of age. AAE ¼ adverse arrhythmic event; CK-MB ¼ creatine kinase-MB. 1137 1138 Liebregts et al. JACC: CARDIOVASCULAR INTERVENTIONS VOL. 10, NO. 11, 2017 JUNE 12, 2017:1134–43 Age-Specific Outcomes of ASA for Obstructive HCM T A B L E 3 Long-Term (>30 Days) Outcomes of 1,197 Patients Following Alcohol Septal Ablation reinterventions during follow-up were similar between the different age groups. #50 Years (n ¼ 369) 51–64 Years (n ¼ 423) $65 Years (n ¼ 405) 6.2 4.6 5.3 4.1* 4.6 3.6‡ Pacemaker implantation 29 (8) 53 (13)* 65 (16)‡ rates following ASA in young, middle-age, and older ICD implantation 21 (6) 18 (4) 11 (3)* patients were 0.8%, 0.8%, and 1.0% per year, NYHA functional class $III 19 (5) 36 (9) 73 (19)‡ respectively (p ¼ 0.90) (Figure 2). Approximately Improvement of $1 NYHA functional class 322 (89) 359 (87) 315 (80)‡ two-thirds of the AAEs were fatal in both young Follow-up (yrs) LONG-TERM OUTCOMES. Follow-up was complete in 99.6% of patients. The long-term (>30 days) AAE and older patients (Table 3). No independent pre- LVOT gradient (mm Hg) 26 31 27 35 26 33 LVOT gradient reduction (%) 76 27 75 29 77 27 Reintervention 39 (11) 44 (10) 30 (7) Repeat ASA 77% 82% 67% factors Myectomy 23% 18% 33% term follow-up (HR: 5.26; 95% CI: 1.13 to 24.51; p ¼ 0.03). ICD implantation following ASA was 5% 11% 3% AAE 19 (5.1) 18 (4.3) 18 (4.4) SCD 63% 56% 72% Myectomy after repeat ASA dictors of AAEs in young and middle-age patients were found. In older patients, $2 conventional risk for SCD predicted AAEs during long- more common in young compared with older patients (6% vs. 3%, p ¼ 0.04). Aborted SCD 5% 6% 6% ICD discharge 32% 39% 22% During a mean follow-up of 5.4 4.2 years, there Annual AAE rate >30 days 0.8% 0.8% 1.0% were 165 deaths in total, which translates into mor- 23 (6.2) 44 (10.4)* 87 (21.5)‡ tality rates of 1% per year in young, 2% per year in HCM-related death 70% 55% 31% middle-age, and 5% per year in older patients Noncardiac death 17% 43% 51% (Table 3). The 1-, 5-, and 10-year survival rates of all Unknown cause of death 13% 2% 18% Annual mortality rate 1.0% 2.1%† 5.1%‡ 1-yr survival 99% 98% 94% 5-yr survival 95% 92% 79% 10-yr survival 91% 80% 55% Mortality ASA patients were 97% (95% CI: 96% to 98%), 89% (95% CI: 89% to 91%), and 76% (95% CI: 73% to 80%), compared with 98%, 92%, and 80%, respectively, in the age- and sex-matched general population (p < 0.05) (Figure 3A). The 1-, 5-, and 10-year survival Values are mean SD, n (%), or %. Values in italics are relative percentages. *p < 0.05. †p < 0.01. ‡p < 0.001 compared with patients #50 years of age. HCM ¼ hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; SCD ¼ sudden cardiac death; other abbreviations as in Tables 1 and 2. rates of patients #50 years were 99% (95% CI: 98% to 100%), 95% (95% CI: 92% to 97%), and 91% (95% CI: 88% to 95%), compared with 100%, 99%, and 97%, respectively, in the age- and sex-matched general population (p < 0.05) (Figure 3B). The 1-, 5-, and 10- F I G U R E 2 Kaplan-Meier Graph of Survival Free of Adverse Arrhythmic Events Following Alcohol Septal Ablation in 369 Patients #50 Years of Age, 423 Patients 51 to 64 Years of Age, and 405 Patients $65 Years of Age year survival rates of patients 51 to 64 years were 98% (95% CI: 97% to 99%), 92% (95% CI: 89% to 95%), and 80% (95% CI: 74% to 86%), compared with 99%, 96%, and 89%, respectively, in the age- and sexmatched general population (p < 0.05) (Figure 3C). The 1-, 5-, and 10-year survival rates of patients $65 years were 94% (95% CI: 92% to 97%), 79% (95% CI: 74% to 84%), and 55% (95% CI: 47% to 64%), compared with 97%, 85%, and 64%, respectively, in the age- and sex-matched general population (p < 0.05) (Figure 3D). The cause of death was HCM related (SCD, heart failure, or stroke) in 70% of the young, 55% of the middle-age, and 31% of the older patients. The opposite pattern was the case for noncardiac deaths (17%, 43%, and 51%, respectively). According to multivariate analyses, independent predictors of all-cause mortality in young patients were age at ASA (HR: 1.09; 95% CI: 1.02 to 1.17; p ¼ 0.02), female sex (HR: 3.03; 95% CI: 1.28 to 7.18; p ¼ 0.01), volume of alcohol injected during ASA (HR: AAE ¼ adverse arrhythmic event; ASA ¼ alcohol septal ablation. 1.55; 95% CI: 1.04 to 2.30; p ¼ 0.03), and LVOT gradient at last checkup (HR: 1.01; 95% CI: 1.00 to Liebregts et al. JACC: CARDIOVASCULAR INTERVENTIONS VOL. 10, NO. 11, 2017 JUNE 12, 2017:1134–43 Age-Specific Outcomes of ASA for Obstructive HCM F I G U R E 3 Kaplan-Meier Graphs of Survival Following Alcohol Septal Ablation in All 1,197 Patients, in 369 Patients #50 Years of Age, in 423 Patients 51 to 64 Years of Age, and in 405 Patients $65 Years of Age, Compared With the Age- and Sex-Matched General Population (A) All patients; (B) patients #50 years of age; (C) patients 51 to 64 years of age; (D) patients $65 years of age. Dotted lines ¼ 95% confidence intervals. ASA ¼ alcohol septal ablation. 1.02; p ¼ 0.02). No independent predictors of mor- patients who received <2.5 ml (n ¼ 213). The 1-, 5-, and tality in middle-age patients were found. Indepen- 10-year survival rates of patients who received <2.5 ml dent predictors of all-cause mortality in older alcohol were 99% (95% CI: 99% to 100%), 98% (95% CI: patients were age at ASA (HR: 1.14; 95% CI: 1.07 to 95% to 100%), and 94% (95% CI: 90% to 99%), 2.21; p < 0.001), and $2 conventional risk factors for compared with 98% (95% CI: 96% to 100%), 91% (95% SCD (HR: 3.13; 95% CI: 1.40 to 7.00; p < 0.01). CI: 86% to 96%), and 89% (95% CI: 83% to 94%), The role of alcohol volume in young ASA patients respectively, in patients who received a higher alcohol was further explored by dividing the cohort into a high volume (p ¼ 0.03) (Figure 4). The annual HCM-related and low alcohol dose groups. A cutoff of 2.5 ml was mortality rate was found to be 0.2% in the <2.5 ml chosen because in a previous analysis, a volume be- alcohol group, compared with 1.2% in the higher tween 1.5 and 2.5 ml was found to be well balanced in alcohol volume group (p < 0.01). Furthermore, pa- terms of efficacy and risk for conduction disturbances tients who received the higher volume of alcohol (11). Six patients (1.6%) were excluded from this anal- developed ysis because data regarding the volume of alcohol kinase-MB 89 IU/l vs. 69 IU/l, p < 0.001), whereas there could not be retrieved. Patients who received $2.5 ml were no differences in LVOT gradient or NYHA func- alcohol (n ¼ 150) had a significantly higher all-cause tional class at long-term follow-up between the 2 and HCM-related mortality rate compared with groups (Table 4). larger infarcts (maximum creatinine 1139 1140 Liebregts et al. JACC: CARDIOVASCULAR INTERVENTIONS VOL. 10, NO. 11, 2017 JUNE 12, 2017:1134–43 Age-Specific Outcomes of ASA for Obstructive HCM patients (16%) underwent repeat ASA, and only 1 F I G U R E 4 Kaplan-Meier Graph of Survival Following Alcohol Septal Ablation in 213 Young (#50 Years) Patients Treated With <2.5 ml of Alcohol Compared With patient (1%) remained in NYHA functional class III or IV at last follow-up. Nine patients had received 150 Young Patients Treated With $2.5 ml of Alcohol ICDs before ASA, and 6 patients were implanted with ICDs after the ASA procedure. Of these 15 patients (18%), 3 received an appropriate ICD shocks during follow-up. Combined with 2 SCDs (4 years after ASA in a 25-year-old man, 10 years after ASA in a 24-year-old woman) and 1 resuscitated cardiac arrest (9 years after ASA in a 35-year-old man), this translated to an AAE rate of 1.0% per year during long-term follow-up. With no other deaths in the very young, this made for an all-cause mortality rate of 0.3% per year. DISCUSSION With almost 1,200 patients from 4 European countries, this is the largest ASA cohort to date. The principal findings of this 5.4-year follow-up study were that: 1) young (#50 years) patients had OUTCOMES IN THE VERY YOUNG. Of the young pa- tients, 82 (21%) were #35 years of age and therefore considered to be “very young” (Figure 1). None of these patients died in relation to the procedure or within the first 30 days post-ASA. One patient (1.2%) experienced in-hospital VT requiring electric cardioversion. Twenty-one patients (26%) developed (transient) complete atrioventricular block, resulting in permanent pacemaker implantation in 4 patients (5%) at last follow-up visit. Thirteen favorable long-term survival following ASA, with an all-cause mortality rate of 1% per year; 2) despite more risk factors for SCD, young patients had a similar AAE rate (0.8% per year) compared with middle-age and older patients; 3) symptom alleviation following ASA in young patients was excellent, with 95% of patients functioning in NYHA functional class I or II at long-term follow-up; 4) the 30day mortality rate in young patients undergoing ASA was very low (0.3%); 5) young patients had one-half the risk for permanent pacemaker implantation compared with older patients; 6) the use of <2.5 ml alcohol for ASA was associated with an T A B L E 4 Outcomes of 363 Patients #50 Years of Age Following Alcohol Septal Ablation improved survival rate in young patients; and 7) ASA in very young (#35 years) patients was safe <2.5 ml (n ¼ 213) $2.5 ml (n ¼ 150) and effective as well. 5.0 4.1 8.0 4.8† Maximum CK-MB (IU/l) 69 (52) 89 (93)† Pacemaker implantation 18 (8%) 11 (7%) NYHA functional class $III 10 (5%) 9 (6%) LVOT gradient (mm Hg) 28 31 23 32 Mortality 6 (2.8) 17 (11.3)† with a median follow-up of 5 years (13). Survival free Follow-up (yrs) PREVIOUS AGE-SPECIFIC ASA STUDIES. Studies reporting on long-term outcomes of young patients following ASA are scarce. In 2014, a study was conducted that included 75 patients #50 years of age Periprocedural mortality 17% 0% of all-cause mortality following ASA at 10 years was HCM-related death 17% 82% found to be 94%. In 2016, a study was reported that Noncardiac death 33% 12% included 217 ASA patients who were divided into Unknown cause of death 33% 6% young (#55 years) and older (>55 years) groups and Annual mortality rate 0.6% 1.4%* 1-yr survival 99% 98% 5-yr survival 98% 91% 10-yr survival 94% 89% followed for 7.6 4.6 years (7). ASA was similarly effective in both age groups for reduction of symptoms at short-term follow-up, and young patients were found to have a lower risk for procedure- Values are mean SD, n (%), or %. Values in italics are relative percentages. *p < 0.05. †p < 0.001 compared with patients receiving <2.5 ml alcohol. Abbreviations as in Table 1. related atrioventricular conduction disturbances. The 5- and 10-year survival of young patients was 95% and 90%, respectively, which was comparable Liebregts et al. JACC: CARDIOVASCULAR INTERVENTIONS VOL. 10, NO. 11, 2017 JUNE 12, 2017:1134–43 Age-Specific Outcomes of ASA for Obstructive HCM with age- and sex-matched patients with non- (6). Of the 50 studies examined in the systematic re- obstructive HCM. These results are in line with those view that accompanied this meta-analysis, only 7 of the present study, except that along with a dif- compared survival rates of their patients with HCM ference in (transient) atrioventricular block, we also with the sex- and age-matched general population: found a 50% lower need for pacemaker implantation Smedira et al. (17) (n ¼ 323, Cleveland Clinic) and in young patients (8% vs. 16% in older patients). Ommen et al. (18) (n ¼ 289, Mayo Clinic) found sur- Furthermore, periprocedural cardiac tamponade and vival rates following myectomy to be comparable death were less frequent in young patients compared with the general population; Schaff et al. (19) with older patients (0.3% vs. 3% and 0.3% vs. 2%, (n ¼ 749, Mayo Clinic), Woo et al. (20) (n ¼ 388, respectively). Symptom alleviation was excellent in Toronto General Hospital), and Sedehi et al. (5) young patients, with improvement of at least 1 NYHA (n ¼ 171, Stanford University Medical Center) found functional class in 89% of patients to an NYHA survival rates following myectomy to be worse than functional class of I or II in 95% of patients at long- the general population; Jensen et al. (8) (n ¼ 279, 4 term follow-up. Of the older patients, only 81% Scandinavian centers), Veselka et al. (9) (n ¼ 178, 2 were in NYHA functional class I or II at last checkup. Czech centers), and Sedehi et al. (5) (n ¼ 52, Stanford However, residual LVOT gradient, reduction in LVOT University Medical Center) found survival rates gradient, and number of reinterventions were com- following ASA to be comparable with the general parable in both groups, and clearly other factors population; and Sorajja et al. (16) (n ¼ 342, Mayo can cause exertional dyspnea, especially in older Clinic) found post-ASA survival to be comparable patients. with the general population and with sex- and Outcomes of very young patients following ASA age-matched myectomy patients. What primarily were favorable as well, with 99% of them functioning differentiates these studies is that the ones with post- in NYHA functional class I or II at last checkup and a intervention survival rates comparable with the further decline in the need for permanent pacemaker general population had <1,700 patient-years of implantation to 5%. Moreover, the AAE rate was follow-up, whereas the studies with a significant similar to the other age groups, and the all-cause survival difference had follow-up of >2,300 patient- mortality rate was only 0.3% per year. years. The present study, with about 6,500 patientyears of follow-up, belongs to the second category. ASA AND SURGICAL MYECTOMY. The American Col- Consequently, our results support that irrespective of lege of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Asso- septal ciation guidelines on HCM from 2011 state that ASA symptomatic obstructive HCM have reduced long- should be reserved for older patients and patients term survival compared with the general popula- with serious comorbidities and give a class III tion. Apart from comparisons with the general reduction therapy, patients with severe recommendation (Level of Evidence: C) for ASA in population, Ommen et al. (18) also reported specif- younger patients if myectomy is a viable option (2). ically on survival of patients #45 years of age and These recommendations reflected the lack of ASA found 92% of these to be alive 10 years post- studies with long-term follow-up, whereas myectomy myectomy. Woo et al. (20) did the same for had been proved to be safe and effective. Despite patients <50 years of age and found a 10-year survival these recommendations, recent reports show that of about 90% following myectomy. These results about 43% of U.S. patients undergo ASA instead of correlate well with the 91% 10-year survival of young myectomy (14), and these numbers are known to be ASA patients found in the present study. Because even higher in Europe (15). Most of the studies symptom improvement was excellent and long- comparing long-term outcomes of ASA and myectomy lasting in young ASA patients as well, we therefore were reported after publication of the 2011 HCM propose that the indication for ASA can be broadened guidelines (3–5,10,16). These more recent studies all to younger patients. showed similar mortality rates following ASA and myectomy, which clearly supports the long-term ASA AND ALCOHOL VOLUME. To date, there has safety of ASA, especially considering that most of been only 1 other study that showed a significant the ASA cohorts were on average older than their survival benefit from the use of a lower alcohol vol- surgical counterparts. A recent meta-analysis of long- ume for ASA. This study, by Kuhn et al. (21), term outcomes of septal reduction therapy found an comprised 2 series: 329 patients treated in a dose- all-cause mortality rate of 1.5% per year following finding study with decreasing amounts of alcohol ASA compared with 1.4% per year following myec- until 2001 (on average 2.9 to 0.9 ml) and 315 patients tomy, and similar annual (aborted) SCD rates as well in the subsequent “low alcohol dose era” treated until 1141 1142 Liebregts et al. JACC: CARDIOVASCULAR INTERVENTIONS VOL. 10, NO. 11, 2017 JUNE 12, 2017:1134–43 Age-Specific Outcomes of ASA for Obstructive HCM 2005 (mean volume 0.8 ml). In the first group, pa- has no complicating factors, the advice should be that tients treated with >2 ml of alcohol showed a higher ASA and surgical myectomy are both safe and effec- mortality rate than patients treated with #2 ml. The tive for relief of symptoms. However, ASA has a 5% to mean follow-up period for this cohort was only 2 16% (depending on the patient’s age) risk for perma- years, however, and the patients treated with a higher nent pacemaker implantation, compared with about alcohol volume were by definition the first patients to 4% after myectomy (6). Furthermore, there is a higher undergo ASA at this center. risk for the need for reintervention following ASA (9% In the present study, the use of a higher volume of in the present study) compared with myectomy (6). alcohol was found to predict all-cause mortality in Patients can subsequently weigh these higher risks young patients. In a recent analysis, alcohol volume following ASA against the somewhat higher burden of of 1.5 to 2.5 ml was found to be well balanced in (rehabilitation from) open heart surgery and make a terms of efficacy and risk for conduction distur- measured decision. bances (11). After we divided our young cohort accordingly, the patients who received <2.5 ml STUDY alcohol were found to have a significantly lower randomized nature of the present study has several all-cause and HCM-related mortality rate compared limitations. In the analysis concerning the role of with patients who received $2.5 ml (Figure 4). alcohol volume in young patients, there was a Furthermore, group potential for bias by indication, because patients who developed larger infarcts, the LVOT gradient and received a higher alcohol volume for ASA might have NYHA functional class at last checkup were compa- had different coronary artery anatomy and/or septal rable between the 2 groups. Of note, patients who pathology received $2.5 ml alcohol were treated on average 5 patients who received less alcohol. However, a Cox years earlier than those treated with <2.5 ml. This proportional regression analysis in young patients trend of decreasing volumes of alcohol over the years with use of basal septal thickness data in millimeters is seen in most ASA studies and may thus further (as opposed to the binary conventional risk factor of improve survival rates in young patients following maximum left ventricular wall thickness $30 mm) ASA in the future. found the same results (not shown). Similar to other PATIENT SELECTION AND SPECIALIZED CARE. In a in the very young patients and young patients treated previous analysis, a higher residual LVOT gradient with <2.5 ml of alcohol were underpowered. There- after ASA was found to predict long-term mortality fore, no comparisons with the general population (11). The present study documented the same asso- were made, and the results of these analyses should ciation, but only in young patients, with an approxi- be interpreted with caution. Finally, we did not cor- mate 1% increase in all-cause mortality for each rect for individual or local alterations of percutaneous millimeter of mercury residual LVOT gradient. This technique. However, all procedures were performed emphasizes the importance of proper selection by experienced interventional cardiologists, and this of patients suitable for ASA, especially in patients implies that our findings are more generalizable than #50 years of age. those of single-center investigations. although the high-volume LIMITATIONS. The (e.g., more retrospective, fibrosis) compared non- with reported studies (5,8,9,16–18), the survival analyses In line with the 2011 American College of Cardiology and 2014 European Society of Cardiology HCM guidelines (1,12), we recommend that all patients CONCLUSIONS undergoing septal reduction therapy should be dis- ASA in young patients with obstructive HCM is safe cussed by a multidisciplinary heart team (consisting and effective for relief of symptoms at long-term of an imaging cardiologist, an interventional cardiol- follow-up. We propose that the indication for ASA ogist experienced with ASA, and a surgeon experi- can be broadened to younger patients. enced with myectomy) to determine the optimal therapy, by taking into account not only age but also ACKNOWLEDGMENT The authors thank J. C. Kelder, factors such as mitral valve anatomy, coronary anat- MD, PhD, Department of Cardiology, St. Antonius omy, existing conduction disturbances, septal thick- Hospital Nieuwegein, for his statistical assistance. ness, comorbidities, and so on. When all of these factors have been weighted against one another, the ADDRESS FOR CORRESPONDENCE: Dr. Max Liebregts, heart team can provide optimal advice, leaving the St. Antonius Hospital, Koekoekslaan 1,3430 EM, Nieuwegein, final decision up to the patient. When an adult patient the Netherlands. E-mail: maxliebregts@gmail.com. Liebregts et al. JACC: CARDIOVASCULAR INTERVENTIONS VOL. 10, NO. 11, 2017 JUNE 12, 2017:1134–43 Age-Specific Outcomes of ASA for Obstructive HCM PERSPECTIVES WHAT IS KNOWN? The American College of Cardiology we propose that the indication for ASA can be broadened Foundation/American Heart Association guidelines to younger patients. reserve ASA for older patients and patients with serious comorbidities. Data on long-term age-specific outcomes WHAT IS NEXT? In the smaller subgroup of very young (#35 years) patients, ASA was found to be safe and effec- after ASA are scarce. tive as well. However, more studies with long-term followWHAT IS NEW? We found that ASA in younger (#50 up of very young patients with HCM undergoing ASA are years) patients with obstructive HCM is safe and effective warranted to confirm these findings. for relief of symptoms at long-term follow-up. Therefore, REFERENCES 1. Sigwart U. Non-surgical myocardial reduction for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. 9. Veselka J, Krejci J, Tomasov P, Zemánek D. Long-term survival after alcohol septal ablation 16. Sorajja P, Ommen SR, Holmes DR Jr., et al. Survival after alcohol septal ablation for obstruc- Lancet 1995;346:211–4. for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy: a comparison with general population. Eur Heart J 2014;35:2040–5. tive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2012;126:2374–80. 2. Gersh BJ, Maron BJ, Bonow RO, et al. 2011 ACCF/ AHA guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:212–60. 3. Vriesendorp PA, Liebregts M, Steggerda RC, et al. Long-term outcomes after medical and invasive treatment in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol HF 2014;2:630–6. 4. Samardhi H, Walters DL, Raffel C, et al. The long-term outcomes of transcoronary ablation of septal hypertrophy compared to surgical myectomy in patients with symptomatic hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2014;83:270–7. 5. Sedehi D, Finocchiaro G, Tibayan Y, et al. Longterm outcomes of septal reduction for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Cardiol 2015;66: 57–62. 6. Liebregts M, Vriesendorp PA, Mahmoodi BK, Schinkel AFL, Michels M, ten Berg JM. A systematic review and meta-analysis of longterm outcomes after septal reduction therapy in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol HF 2015;3:896–905. 7. Liebregts M, Steggerda RC, Vriesendorp PA, et al. Long-term outcome of alcohol septal abla- 10. Steggerda RC, Damman K, Balt JC, Liebregts M, ten Berg JM, van den Berg MP. Periprocedural complications and long-term outcome after alcohol septal ablation versus surgical myectomy in hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy: a single-centre experience. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv 2014;7:1227–34. 11. Veselka J, Jensen MK, Liebregts M, et al. Longterm clinical outcome after alcohol septal ablation for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: results from the Euro-ASA registry. Eur Heart J 2016;37:1517–23. 12. Elliott PM, Anastasakis A, Borger MA, et al. 2014 ESC guidelines on diagnosis and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2014;35: 2733–79. 13. Veselka J, Krejci J, Tomasov P, et al. Survival of patients #50 years of age after alcohol septal ablation for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Can J Cardiol 2014;30:634–8. 17. Smedira NG, Lytle BW, Lever HM, et al. Current effectiveness and risks of isolated septal myectomy for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Ann Thorac Surg 2008;85:127–33. 18. Ommen SR, Maron BJ, Olivotto I, et al. Longterm effects of surgical septal myectomy on survival in patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;46: 470–6. 19. Schaff HV, Dearani JA, Ommen SR, Sorajja P, Nishimura RA. Expanding the indication for septal myectomy in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: results of operation in patients with latent obstruction. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012; 143:303–9. 20. Woo A, Williams WG, Choi R, et al. Clinical and echocardiographic determinants of long-term survival after surgical myectomy in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2005; 111:2033–41. 21. Kuhn H, Lorenz T, Lieder F, et al. Survival after transcoronary ablation of septal hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (TASH): a 10 year experience. Clin Res Cardiol 2008;97:234–43. 14. Kim LK, Swaminathan RV, Looser P, et al. Hospital volume outcomes after septal myectomy tion for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in the young and the elderly. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv 2016;9:463–9. and alcohol septal ablation for treatment of obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: US Nationwide Inpatient Database 2003–2011. JAMA Cardiol 2016;1:324–32. 8. Jensen MK, Almaas VM, Jacobsson L, et al. Long- 15. Maron BJ, Yacoub M, Dearani JA. Controversies term outcome of percutaneous transluminal septal myocardial ablation in hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy: a Scandinavian multicenter study. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2011;4:256–65. in cardiovascular medicine. Benefits of surgery in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: bring myectomy back for European patients. Eur Heart J 2011;32:1055–8. KEY WORDS alcohol septal ablation, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, septal reduction therapy Go to http://www.acc. org/jacc-journals-cme to take the CME/MOC quiz for this article. 1143