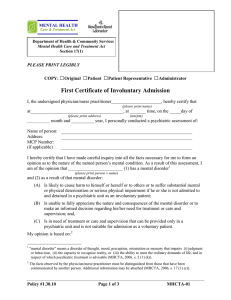

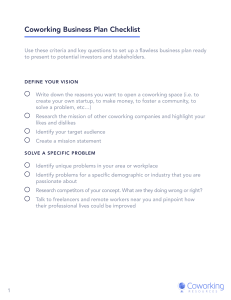

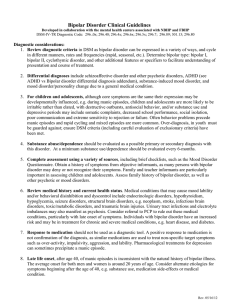

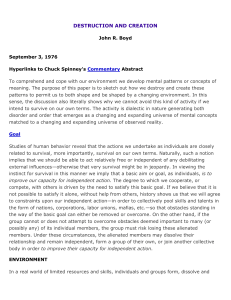

Original Research Reports Corticosteroid-Induced Psychotic and Mood Disorders Diagnosis Defined by DSM-IV and Clinical Pictures KEN WADA, M.D., NORIHITO YAMADA, M.D. TOSHIKI SATO, M.D., HIROSHI SUZUKI, M.D. MASAHITO MIKI, M.D., YOMEI LEE, M.D. KAZUFUMI AKIYAMA, M.D., SHIGETOSHI KURODA, M.D. The authors investigated long-term outcome and treatment strategy of corticosteroid-induced psychotic and mood disorders as defined by DSM-IV. Review of medical records of 2,069 referral patients revealed 18 applicable patients. Their clinical characteristics, longitudinal courses, and treatments were studied. The authors identified 15 patients with mood disorder and 3 patients with psychotic disorder. Increasing doses or resumption of corticosteroids had the strongest influence on the psychiatric course. These two corticosteroid-induced psychiatric disorders may have different pathophysiological substrates closely related to patient vulnerability. Effective psychopharmacological treatment options were indicated with consideration being given to the underlying diseases. (Psychosomatics 2001; 42:461–466) C orticosteroids often induce psychiatric syndromes, including depression, mania, psychosis, and delir1–8 ium. The syndromes are conventionally known as “steroid psychosis,” which is regarded to be a representative exogenous psychiatric disorder. However, steroid psychosis is not a specific clinical entity but consists of heterogeneous syndromes with obviously different pathophysiological mechanisms. Established diagnostic criteria such as those in DSM-IV have scarcely been used in previous studies to evaluate the psychiatric symptoms. Both the symptoms and the diagnosis of steroid psychosis are ambiguous. Corticosteroids can provoke both mania and depression that clinically appear opposite to each other. Conversely, it is suggested that abnormality of the hypothalamo-pituitaryadrenal axis is associated with pathophysiology in mood disorders.9 Thus, clinical studies of psychiatric syndromes induced by corticosteroid treatment are challenging and can shed some light on the pathomechanisms of endogenous psychiatric disorders. There is an urgent need for clinical research focused on the longitudinal course and therapeutic response of these cases. Psychosomatics 42:6, November-December 2001 Patients treated with corticosteroids should receive intensive or long-term maintenance treatment because of exacerbations of their underlying diseases. Recurrent psychiatric syndromes induced by corticosteroids can therefore be observed in clinical practice. When corticosteroidinduced psychiatric syndromes emerge, physicians have difficulty in treating the underlying medical diseases. Although convincing data on recurrence and prophylaxis are needed for psychiatric intervention, previous studies of “steroid psychosis” have directed little attention to longterm outcome and treatment strategy.10–16 This study of patients with corticosteroid-induced psychotic and mood disorder, as defined by DSM-IV, adReceived November 15, 2000; revised March 23, 2001; accepted March 12, 2001. From the Department of Neuropsychiatry, Okayama University Medical School 2-5-1, Shikata-cho, Okayama 700-8558, Japan, Department of Psychiatry, Hiroshima City Hospital, 7-33, Moto-machi, Naka-ku, Hiroshima 730-8518, Japan. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Wada Department of Psychiatry, Hiroshima City Hospital, 7-33, Moto-machi, Naka-ku, Hiroshima 730-8518, Japan. E-mail: kenwada@do3.enjoy.ne.jp Copyright 䉷 2001 The Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine. 461 Steroid Psychosis dressed the following questions. 1) Which is the more frequent manifestation, psychosis or mood disorder? 2) Are there any symptomatological characteristics in each patient group? 3) What influences the longitudinal course? 4) What is the appropriate therapeutic intervention? METHODS From 1990 to 1999, 2,069 patients were referred from other departments to the Department of Neuropsychiatry, Okayama University Medical School. Review of the records from our department revealed that 18 patients fulfilled the following criteria: 1) no previous psychiatric history and first referral to our department during the examination period; 2) DSM-IV criteria for corticosteroid-induced psychotic or mood disorder; and 3) psychiatric symptoms continuing for at least 1 week. Although DSM-IV criteria do not specify the duration of symptoms for substanceinduced psychotic or mood disorder, the third criterion was employed to exclude transient mood change. By reviewing notes and evaluations of these cases by consultant psychiatrists, we aimed to elucidate the clinical characteristics including the frequency of recurrence, psychiatric symptomatology, response to treatment, and outcome. The nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test was used for statistical analyses, with a significance level of P⬍0.05. RESULTS We identified 15 patients with mood disorder and 3 patients with psychotic disorder. The prevalence rate of these disorders among the referred cases was 0.87%. The sample consisted of 4 men and 14 women whose age at onset ranged from 18 to 68. Their first psychiatric episode occurred 1 to 20 weeks after commencement of corticosteroid treatment. Oral prednisolone was most frequently administered. Intravenous methylprednisolone was given to patients for corticosteroid pulse therapy at a dose of 500 mg or 1 g/day for 3 consecutive days. Eight of the mood disorder patients had a single episode and seven had recurrent episodes (Table 1). It is interesting that the first mood episode was manic or hypomanic in five patients each in both the single-episode and recurrent subgroups. All except two patients had their first mood episode after the first corticosteroid treatment. The average age of the recurrent subgroup was lower than that of the single-episode subgroup. Maximum prescribed doses of corticosteroid and latency to the onset were not different between the two patient subgroups. According to 462 underlying diseases and disease severity, doses equivalent to prednisone 30–60 mg/day were initially prescribed. Recurrent patients showed several interesting clinical features (Table 1).17 All seven patients presented bipolar disorder and none had recurrent depressive disorder. These patients presented 19 mood disorder episodes, 11 manic and 8 depressive. Five of the seven recurrent patients had manic episodes accompanied by psychotic features such as auditory hallucinations and persecutory delusions. During the follow-up period, five patients showed mood episodes (four depressive and one manic) that were not related to either alterations in dose or resumption of corticosteroids. Various psychosocial stressors, such as occupational difficulties and marital problems, preceded their mood episodes. Four of the five patients who received high doses of intravenous methylprednisolone rapidly became manic or hypomanic. Depressive stupor was observed in two patients and two other patients attempted suicide by self-mutilation. Six patients showed depressive episodes, four of whom were diagnosed as severe. No patient developed a depressive episode that coincided with psychotic features. Among the single-episode patients (n⳱8), one showed manic episode with psychotic features and two became rapidly depressive after steroid pulse therapy. Each of three depressive episodes was relatively mild, and no patient developed either depressive stupor or suicidality. Because underlying medical diseases of the eight patients were brought under control, corticosteroids were withdrawn or titrated to a low maintenance level. Neither increasing doses nor resumption of corticosteroids was indicated as the triggering factor in these patients except one patient who showed manic episodes after the second course of treatment. The mood disorder patients were treated with mood stabilizers, antipsychotics, and antidepressants (Table 2). Corticosteroids were simultaneously tapered as quickly as possible. Manic episodes were treated with antipsychotics alone or in combination with mood stabilizers. Carbamazepine and valproate were the preferred mood stabilizers. Antipsychotics were effective at relatively low doses. Depressive episodes were effectively treated with antidepressants (including tricyclics), except for one patient who exhibited drowsiness as an adverse effect. Intravenous clomipramine was very effective in two patients with depressive stupor. No patient became more depressed after receiving antidepressants for depressive symptoms. One patient with four previous mood episodes experienced no recurrence under maintenance treatment with carbamazepine (600 mg/day) despite receiving three additional Psychosomatics 42:6, November-December 2001 Wada et al. TABLE 1. Clinical characteristics of mood disorder patients Subgroup Gender Age at Onset (years) Underlying Disease Polarity Psychotic Features Pulse Therapy Recurrent Case 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 F F F F M M M 18 21 23 31 47 42 68 Nephrotic syndrome Polymyositis Ulcerative colitis SLE SLE Kidney transplant Nephrotic syndrome M-D*-D-M D-M-D* M-D* D-M M-M M-M-D-M* M-D* Ⳮ Ⳮ Ⳮ Ⳮ Ⳮ - Rapidly induced mania Rapidly induced mania Not done Induced depression Not done Rapidly induced mania Rapidly induced mania Single Episode Case 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 F F F F F F F M 43 46 47 50 54 58 63 65 Nephrotic syndrome Polymyositis SLE Pemphigus vulgaris Polyarteritis nodosa Dermatomyositis Bullous pemphigoid Nephrotic syndrome D D D M M M M M Ⳮ - Done without exacerbation Rapidly induced depression Rapidly induced depression Not done Not done Not done Not done Not done Note: M ⳱ manic and hypomanic episode; D ⳱ depressive episode; * ⳱ mood episode unrelated to steroid therapy; SLE ⳱ systemic lupus erythematosus. courses of corticosteroid pulse therapy. No severe adverse effects were observed except for rashes induced by carbamazepine. Each episode of these 15 patients had a relatively good outcome with full remission after 1–3 months. Two of the three psychotic disorder patients were recurrent. Underlying medical diseases of these three patients TABLE 2. Effective treatments for mood disorder patients Subgroup Mania Depression Prophylaxis Recurrent Case 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 CBZ AP AP AP AP VPA CBZ nTCAⳭCZP TCA TCA TCA No episodes nTCA nTCA CBZ Li Not done AP Not done VPA None No episodes No episodes No episodes AP VPA AP AP VPA TCA Steroid tapering only nTCA No episodes No episodes No episodes No episodes No episodes Not done Not done Not done Not done Not done Not done Not done Not done Single Episode Case 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Note: AP ⳱ antipsychotic; CBZ carbamazepine; CZP clonazepam; Li lithium carbonate; nTCA non-tricyclic antidepressant; TCA tricyclic antidepressant; VPA valproate. Psychosomatics 42:6, November-December 2001 were Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (two patients) and bullous pemphigoid. All three patients initially showed typical schizophrenic symptoms such as persecutory delusions, auditory hallucinations and disorganized behaviors. However, the two recurrent patients had atypical symptoms, including depressed mood, agitation, and progressive reduction in contact and reactivity, in the following episodes. Latency of onset ranged from 2 to 4 weeks. Maximum oral dosage of corticosteroid did not differ from that of mood disorder patients. Only one patient received corticosteroid pulse therapy without showing any exacerbation of psychotic symptoms. Every patient was effectively treated with a relatively low dose of haloperidol (ⱕ3 mg/day). DISCUSSION 1) Which is the more frequent manifestation, psychosis or mood disorder? It is widely accepted that affective symptoms are the most prominent clinical features in “steroid psychosis.”2–8 Lewis and Smith4 reported that there were seven mania, one depression and two psychoses in their original series. They also cited 60 mood disorders and 11 psychoses from their review of the literature. Ling et al.5 found 45 patients with mood disorder and 9 with acute psychosis. In keeping with these studies, we identified more mood disorders than psychotic disorders [15:3], as defined by DSM-IV. Of the 463 Steroid Psychosis 15 mood disorder patients, 6 (40%) had manic episodes with psychotic features, indicating a higher incidence of psychotic features in corticosteroid-induced mania than in primary mania. Goodwin and Jamison18 estimated that among patients with primary mania, 18% had auditory hallucinations and 28% had persecutory delusions. This research shows that corticosteroids tend to induce mood disorder, which is frequently accompanied by psychotic features and, at a lower incidence, psychotic disorder. Corticosteroids can affect various psychiatric functions, including mood, cognition, and thought, and can induce different psychiatric syndromes based on the patient’s vulnerability. Furthermore, we did not observe any recurrent patients who emerged into other types of disorder during the examination period. These two corticosteroidinduced psychiatric syndromes may have distinct pathophysiological substrates. 2) Are there any “symptomatological characteristics” in each patient group? Among 15 mood disorder patients, 10 were manic or hypomanic at onset and 12 presented with bipolar disorder. Although there is a possibility that not every patient with mild affective symptoms was referred to a psychiatrist, we identified no patient with recurrent monopolar depressive episodes. Therefore, it is quite plausible that corticosteroidinduced mood disorder and primary bipolar disorder have common biological substrates. In primary bipolar disorders, both manic and depressive episodes are considered to occur with equal frequency, and the latter are predominant in female patients in the longitudinal course.18 Although some previous reports of “steroid psychosis”4,5 demonstrated a higher incidence of depression than mania, recurrent cases were rarely included in these studies. Taken together, our findings from a predominantly female sample confirm a higher incidence of mania in corticosteroid-induced mood disorder.17 A number of previous studies reported that steroid psychosis often involves variable and atypical clinical features. This characteristic could have resulted from the heterogeneity of the study subjects who were not diagnosed according to established criteria. However, our findings suggest that it partially accounts for manic episodes, which are frequently accompanied by psychotic features. Our two psychotic disorder patients recurred with atypical symptoms, which is consistent with previous findings.2,4,5 It is of clinical interest that 16 of the 18 patients showed subacute onset ranging from 2 to 12 weeks in their first psychiatric episode. This may indicate that psychiatric episodes develop after a certain secondary intracerebral 464 change, such as gene expression and receptor sensitivity following corticosteroid treatment. Recurrent episodes did not occur sooner after corticosteroid resumption or escalation than did earlier episodes. Although rather acute onset has been reported previously,2,4,5 this is probably because acute heterogeneous syndromes such as delirium and transient mood change were included. 3) What influences the longitudinal course? Increased doses or resumption of corticosteroids, whether the underlying medical disease continues to be stable or not, had the strongest influence on the psychiatric course. In all nine patients with single episodes, corticosteroids were withdrawn or titrated to low maintenance doses during the examination period. However, five of the seven recurrent mood disorder patients became manic or depressive without altering the dosage of corticosteroids. This finding suggests that some patients could acquire susceptibility to mood disorders once corticosteroids are given. These patients would probably show recurrent course due equally to subsequent treatment and psychosocial stressors. In other words, this intrinsic susceptibility would not be specific to subsequent corticosteroid challenge. Despite our small number of subjects, we could not observe recurrences unrelated to corticosteroid treatment in psychotic disorder patients. It may be speculative that some differences exist in the tendency to acquire susceptibility after initial corticosteroid treatment between these two corticosteroid-induced psychiatric syndromes. A significant age difference was observed between two mood disorder patient subgroups. Our data could not fully explain why age at onset is lower in recurrent patients. There is a possibility that repeated corticosteroid treatment might be required for younger patients with onset of underlying medical diseases. Alternatively, younger patients may acquire the susceptibility mentioned above more easily than older patients. However, single-episode mood disorder patients might have had recurrences, with subsequent corticosteroid treatment or dose increases. 4) What is the appropriate therapeutic intervention? A few reports11,12,19 have suggested that lithium carbonate is effective for both mania and depression induced by corticosteroids. However, in clinical practice, diseases treated with corticosteroids, such as nephrotic syndromes or SLE, are often accompanied by renal dysfunction. Lithium carbonate is contraindicated and should be avoided in such patients. In our series, carbamazepine was effective in two patients and valproate was effective in three other patients. Carbamazepine also appeared to have prophylactic effect in one patient. The most beneficial mood stabiPsychosomatics 42:6, November-December 2001 Wada et al. lizer must be chosen, taking into consideration the underlying somatic dysfunction.14,15,20 Carbamazepine and valproate should be evaluated as alternative treatments and for prophylaxis. To treat manic episodes as quickly as possible, antipsychotics were used singly or in combination with mood stabilizers. Although some previous reports2,13,19 indicated the effectiveness of phenothiazines, in our series butyrophenones4 and zotepine, a thiepin derivative widely used as an antimanic agent in Japan, were very effective. Recent treatment guidelines for mania in primary bipolar disorders21 recommend adjuvant use of high-potency antipsychotics. If they are indicated, antipsychotics should be given for corticosteroid-induced mania. Some previous reports2,10 demonstrated that antidepressants were contraindicated for steroid psychosis. However, we experienced no exacerbated cases among the eight patients who received antidepressants. Even intravenous clomipramine was apparently effective in two patients who had deteriorated into depressive stupor. The four exacerbated cases reported by Hall et al.2 manifested some hypomanic or mixed symptoms for which antidepressants are not primarily recommended. Severe depressive episodes with suicidality often occur in corticosteroid-induced mood disorder.22 The indication for antidepressants, including newer agents such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors,16 must be re-examined in these patients. Good therapeutic response to low doses of haloperidol is a characteristic of corticosteroid-induced psychotic disorder.4,10 It may have pathophysiological substrates in common with some schizophrenia patients who show remarkable response to low doses of antidopaminergic agents. Further longitudinal investigations of corticosteroid-induced psychotic disorder patients seem warranted to clarify this hypothesis. Steroid pulse therapy, represented by high-dose methylprednisolone, is commonly used for more rapid effectiveness and less toxicity. To date, no study has shown that psychiatric complications occur more frequently with pulse therapy than with oral administration.23–25 In our series, four patients became rapidly manic or hypomanic and two became rapidly depressive after pulse therapy. These rapid exacerbations may indicate that extremely high doses of corticosteroids induce significant psychological and behavioral changes in susceptible subjects. We suggest that pulse therapy must be carefully prescribed for patients with corticosteroid-induced mood disorders. Continuous support by psychiatrists and their close cooperation with other physicians will contribute to the quality of life of patients undergoing long-term corticosteroid treatment. These patients often suffer from recurrence of underlying diseases and inevitably experience various psychosocial difficulties. Preventive strategies for psychiatric relapses from psychosocial stressors are strongly needed, since these episodes are not rare. Particular attention should be paid to younger patients with onset of corticosteroidinduced mood disorders, since they are more likely to have recurrences and psychotic features. Psychiatrists should advise other physicians on corticosteroid treatment plans, especially the indications of steroid pulse therapy. References 1. Wolkowitz OW, Reus VI, Canick J, e al: Glucocorticoid medication, memory and steroid psychosis in medical illness. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1997; 823:81–96 2. Hall RCW, Popkin MK, Stickney SK, et al: Presentation of the steroid psychoses. J Nerv Ment Dis 1979; 167:229–236 3. Kershner P, Cheng RW: Psychiatric side effects of steroid therapy. Psychosomatics 1989; 30:135–139 4. Lewis DA, Smith RE: Steroid induced psychiatric syndromes. J Affect Dis 1983; 5:319–332 5. Ling MHM, Perry PJ, Tsuang MT: Side effects of corticosteroid therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981; 18:471–477 6. Reckart MD, Eisendrath SJ: Exogenous corticosteroid effects on mood and cognition. Int J Psychosom 1990; 37:57–61 7. Naber D, Sand P, Heigl B: Psychopathological and neuropsychological effects of 8-days’ corticosteroid treatment. Psychoendocrinology 1996; 21:25–31 8. Brown ES, Suppes T: Mood symptoms during corticosteroid therapy: a review. Harv Rev Psychiatry 1998; 5:239–246 9. Ribeiro SCM, Tandon R, Grunhaus L, et al: The DST as a predictor of outcome in depression: a meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 150:1618–1629 Psychosomatics 42:6, November-December 2001 10. Davis JM, Leach A, Merk B, et al: Treatment of steroid psychosis. Psychiatr Ann 1992; 22:487–491 11. Falk WE, Mahnke MW, Poskanzer DC: Lithium prophylaxis of corticotropin-induced psychosis. JAMA 1979; 241:1011–1012 12. Terao T, Yoshimura R, Shiratsuchi T, et al: Effects of lithium on steroid-induced depression. Biol Psychiatry 1997; 41:1225–1226 13. Bloch M, Gur E, Shalev A: Chlorpromazine prophylaxis of steroid-induced psychosis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1994; 16:42–44 14. Lynn DJ: Lithium in steroid-induced depression (letter). Br J Psychiatry 1995; 166:264 15. Sechi G, Piras MR, Demurtas A, et al: Dexamethasone-induced schizoaffective-like state in multiple sclerosis: prophylaxis and treatment with carbamazepine. Clin Neuropharmacol 1987; 10:453–457 16. Beshay H, Pumariega AJ: Sertraline treatment of mood disorder associated with prednisone: a case report. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 1998; 8:187–193 17. Wada K, Yamada N, Suzuki H, et al: Recurrent cases of corticosteroid-induced mood disorder: clinical characteristics and treatment. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61:261–267 465 Steroid Psychosis 18. Goodwin FK, Jamison KR: Manic -Depressive Illness. New York, Oxford University Press, 1990 19. Blazer DG, Petrie WM, Wilson WP: Affective Psychoses following renal transplant. Dis Nerv Syst 1976; 128:1467–1473 20. Kahn D, Stevenson E, Douglas CG: Effect of sodium valproate in three patients with organic brain syndromes. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:1010–1011 21. Frances A, Docherty JP, Kahn DA: The Expert Consensus Guideline Series: treatment of bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57(suppl. 12A):1–88 466 22. Braunig P, Bleistein J, Rao ML: Suicidality and corticosteroidinduced psychosis. Biol Psychiatry 1989; 26:209–220 23. Wysenbeck AJ, Leibovici L, Zoldan J: Acute central nervous system complications of pulse steroid therapy in patients with SLE. J Rheumatol 1990; 17:1695–1696 24. Baethge BA, Lidsky MD, Goldberg JW: A study of adverse effects of high-dose intravenous (pulse) methylprednisolone therapy in patients with rheumatic disease. Ann Pharmacother 1992; 26:316– 320 25. Wolheim FA: Acute and long term complications of corticosteroid pulse therapy. Scand J Rheumatol 1984; 54:27–32 Psychosomatics 42:6, November-December 2001