Rodriguez Araujo et al 2019 - Germinación de Ephedra ochreata

Anuncio

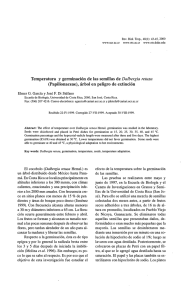

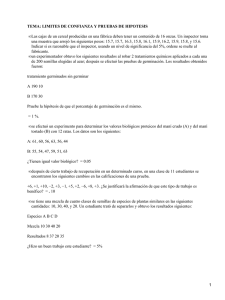

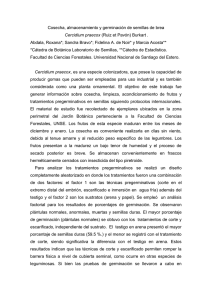

GERMINACIÓN DE Ephedra ochreata Miers PARA LA RESTAURACIÓN DE AMBIENTES ÁRIDOS EN ARGENTINA GERMINATION OF Ephedra ochreata Miers: CONTRIBUTION FOR PRODUCTIVE RESTORATION OF ARID ENVIRONMENTS IN ARGENTINA María E. Rodríguez-Araujo1*, Clara Milano2, Daniel R. Pérez3 Universidad Nacional del Comahue, CONICET, Facultad de Ciencias del Ambiente y la Salud, Laboratorio de Rehabilitación y Restauración de Ecosistemas Áridos y Semiáridos. Buenos Aires 1400, Neuquén, Argentina (CP 8300). (emilia_araujo08@yahoo.com.ar). 2Universidad Nacional del Sur, Departamento de Agronomía, Laboratorio de Pastizales Naturales. San Andrés 800, Bahía Blanca, Buenos Aires, Argentina (CP 8000). 1y3 RESUMEN ABSTRACT Ephedra ochreata Miers es un arbusto nativo de zonas áridas de Argentina con usos actuales y potenciales, para las comunidades rurales por sus conos comestibles y su valor forrajero. Ademas se adapta, a áreas afectadas por desertificación severa. Estos dos rasgos permiten plantear su posible uso para la restauración productiva, una actividad que propone la recuperación de la estructura y función de ecosistemas degradados, simultáneamente con el uso productivo de la tierra. Para ello, se requiere primero determinar los tratamientos pregerminativos que permitan la producción de plántulas o su siembra en grandes cantidades. La hipótesis del estudio fue que los tratamientos eficientes para germinar otras Ephedraceae son efectivos para esta especie y que la procedencia de las semillas afecta las características seminales tales como germinación, tamaño y peso. El objetivo de la investigación fue comparar el tamaño y peso de las semillas y el efecto sobre la germinación de cuatro tratamientos pregerminativos: remojo (RE), frío-húmedo (FH), escarificación química (EQ), y testigo (T), en semillas procedentes del extremo oeste (Monte Neuquino: MN) y este (Dunas Costeras: DC) de la distribución patagónica de la especie. El diseño experimental fue de bloques completamente aleatorizados con tres réplicas de 30 semillas por tratamiento. Los resultados se analizaron con ANDEVA (p£0.05). Las semillas de MN fueron más grandes y pesadas que las de DC y presentaron mayor germinación. El tratamiento FH aceleró la germinación de las semillas de MN y produjo 98.9 % de germinación a los 14 d de comenzado el experimento. Las semillas de DC tuvieron menor tiempo de germinación con FH y RE comparadas con los tratamientos. Estos resultados aportan información relevante para la producción en viveros o para la siembra directa de E. Ephedra ochreata Miers is a shrub native to arid areas of Argentina that is useful for rural communities because its edible cones provide food and livestock forage. Besides it is able to inhabit areas affected by severe desertification. Given these two features, it is considered a potentially useful species for productive restoration, a type of ecological restoration that proposes the recovery of the structure and function of degraded ecosystems, while at the same time using the land for productive purposes. For this goal, it is necessary determine the simplest way to achieve high and homogeneous seed germination to optimize the production of seedlings in nursery gardens or direct seeding in the field. The hypothesis of this study was that germination treatments that are effective in other Ephedraceae will also improve germination in this species and that the provenance of the seeds will affect characteristics such as size, weight, and germination rate. The objective of this research was to compare the size and weight of the seeds from two areas of the Patagonian distribution of the species: the extreme west (Monte Neuquino: MN) and east (Coastal Dunes: CD). Then, we compared the effects of four pregerminative treatments: soaking (SO), cold-wet (CW), chemical scarification (CE) and control (C) on germination rates. The experimental design was completely randomized with three replicates of 30 seeds per treatment. The results were analyzed with ANOVA (p£0.05). The seeds from MN were larger and heavier than those of CD and had higher germination rates overall. The CW treatment accelerated the germination of MN seeds and produced 98.9 % of germination at 14 d after treatment. The seeds from CD had shorter germination time with CW and SO compared to the other treatments. These results provide relevant information for nursery production for outplantings or direct seeding of E. ochreata for use in productive restoration of arid zones of Argentina. * Autor responsable v Author for correspondence. Recibido: junio, 2018. Aprobado: agosto, 2018. Publicado como ARTÍCULO en Agrociencia 53: 617-629. 2019. 617 AGROCIENCIA, 16 de mayo - 30 de junio, 2019 ochreata y su uso en restauración productiva de zonas áridas de Argentina. Key words: desertificación, Ephedra ochreata, Monte Austral, Patagonia Argentina, tratamientos pregerminativos. Palabras claves: desertificación, Ephedra ochreata, Monte Austral, Patagonia Argentina, tratamientos pregerminativos. INTRODUCTION INTRODUCCIÓN L as zonas áridas, semiáridas y subhúmedas se caracterizan por precipitaciones escasas y poco predecibles y tasas de evapotranspiración altas (Reynolds et al., 2007). Estas condiciones generan estrés en las especies vegetales y limitan la productividad primaria y el reciclaje de nutrientes (Safriel y Adeel, 2005). El 69 % de los ecosistemas áridos del mundo presentan algún grado de degradación (Dregne et al., 1991); de ellos, 10 a 20 % muestran degradación severa (Zika y Erb, 2009). La Patagonia Argentina tiene 78.5 millones ha de ecosistemas áridos y semiáridos, de las cuales 93.6 % están desertificadas (Mazzonia y Vázquez, 2009). La restauración ecológica es una herramienta para afrontar los problemas derivados de la desertificación a escala global y de las zonas áridas y semiáridas de la Argentina (Reynolds et al., 2005; Pérez et al., 2011; Pérez et al., 2017). La combinación de los conceptos de restauración ecológica y producción agropecuaria sostenible, a través de técnicas agroforestales y agroecológicas para la restauración productiva (Ceccon, 2013), es una alternativa para la recuperación de ambientes degradados que combina beneficios sociales y ecológicos (MartínezRomero y Ceccon, 2016). Ephedra ochreata se puede utilizar en la restauración productiva por: 1) su aptitud para crecer en suelos pobres y con baja cobertura vegetal, en zonas con precipitaciones escasas y vientos intensos; 2) su calidad nutricional como recurso forrajero para el ganado (Gandullo et al., 2004); 3) sus conos comestibles que se pueden utilizar en la producción artesanal de dulces, licores y otros productos regionales (Rapoport et al., 2011); y 4) sus propiedades medicinales reconocidas por los pueblos mapuches originarios del sur argentino y corroboradas por Ricco et al. (2003). Un obstáculo para el uso de especies nativas en la restauración radica en la imposibilidad de obtener una germinación alta debido a las formas complejas de dormición seminal que poseen muchas plantas silvestres, en especial las de zonas áridas (Baskin y Baskin, 2014). Las estrategias para interrumpirla son 618 VOLUMEN 53, NÚMERO 4 T he arid, semi-arid and sub-humid zones are characterized by scarce and unpredictable rainfall and high evapotranspiration rates (Reynolds et al., 2007). These conditions generate stress in plant species and limit primary productivity and nutrient cycling (Safriel and Adeel, 2005). Sixty nine percent of the arid ecosystems of the world present some degree of degradation (Dregne et al., 1991); of those, 10 to 20 % show severe degradation (Zika and Erb, 2009). Argentinian Patagonia comprises 78.5 million ha of arid and semi-arid ecosystems, of which 93.6 % are desertified (Mazzonia and Vázquez, 2009). Ecological restoration is a tool to address the problems arising from desertification, both globally and in the arid and semi-arid zones of Argentina (Reynolds et al., 2005; Busso and Pérez 2018; Pérez et al. 2019a; Pérez et al. 2019b). Productive restoration is a combination of the concepts of ecological restoration and sustainable agricultural production using agroforestry and agroecology (Ceccon, 2013) that combines social and ecological benefits as an option for the recovery of degraded environments (Martinez-Romero and Ceccon, 2016). Ephedra ochreata is a potentially useful plant for productive restoration due to its: 1) ability to grow in poor soils and with little plant cover, in areas with low rainfall and intense winds; 2) nutritional value as a forage resource for livestock (Gandullo et al., 2004); 3) edible cones, which may be used in the artisanal production of sweets, liqueurs and other regional products (Rapoport et al., 2011); and 4) medicinal properties, recognized by the native Mapuche people of southern Argentina and corroborated by Ricco et al. (2003). An obstacle to the use of native species in restoration lies in the difficulty of obtaining high germination due to the complex forms of seminal dormancy that many wild plants possess, especially those of arid zones (Baskin and Baskin, 2014). There are many strategies for interrupting dormancy and they vary among species and geographic areas; therefore, species-specific studies are needed (PérezDomínguez et al., 2013). Germination has been studied in some Ephedra species (Williams et al., 1974; GERMINACIÓN DE Ephedra ochreata Miers PARA LA RESTAURACIÓN DE AMBIENTES ÁRIDOS EN ARGENTINA múltiples y varían con las especies y áreas geográficas, por lo cual es necesario un estudio para cada especie (Pérez-Domínguez et al., 2013). La germinación se ha estudiado en algunas especies de Ephedra (Williams et al., 1974; Anderson, 2006) como E. alata ssp. alenda que habita biotopos extremadamente secos y se evaluó para utilizarse en la restauración de ambientes desérticos del Sahara (Derbel et al., 2010). Sin embargo, no hay estudios sobre la germinación de E. ochreata y se desconoce su respuesta ante tratamientos pregerminativos en semillas con diferente procedencia. Tanto para su producción en viveros como para su potencial aplicación en siembra directa y restauración productiva, se requiere información sobre estas características agronómicas y biológicas básicas (Pérez et al. 2017; Pérez et al. 2019a; Pérez et al. 2019b). Por lo tanto el objetivo de este estudio fue aportar conocimientos sobre la efectividad de cuatro tratamientos pregerminativos en semillas de E. ochreata, provenientes de los extremos este y oeste de la Patagonia Argentina, con el fin de establecer las bases para su uso en restauración productiva. La hipótesis fue que los tratamientos eficientes para germinar otras Ephedraceae son efectivos para esta especie y que la procedencia de las semillas afecta las características seminales tales como germinación, tamaño y peso. MATERIALES Y MÉTODOS Características de Ephedra ochreata Miers El género Ephedra L., de la familia Ephedraceae (Gnetales) incluye 60 especies distribuidas en desiertos y regiones áridas del mundo. Éste es uno de los pocos taxa de gimnospermas con una estructura vegetativa altamente reducida y adaptado a la extrema aridez (Ickert-Bond y Wojciechowski, 2004). Ephedra ochreata se conoce en Argentina como “solupe”, “pico de loro”, “efedra” o “fruta del pichi” y habita en la entidad bioclimática diagonal árida del país (Gandullo et al., 2004; Martínez, 2013). Fuera del territorio argentino solo hay registros de ejemplares aislados en Chile, restringidos a una única zona de recolección (Saldivia et al., 2008). La especie es de hábito arbustivo, dioica, perenne y puede alcanzar hasta 1.5 m de altura. Los tallos son fotosintéticos, de 1.5 a 3 mm de diámetro, sus hojas están dispuestas en verticilos Anderson, 2006), such as E. alata ssp. alenda, which inhabits extremely dry biotopes and was evaluated for use in the restoration of desert environments of the Sahara (Derbel et al., 2010). However, there are no studies of the germination of E. ochreata and the response to pregerminative treatments of seeds of different geographic origins is unknown. This basic agronomic and biological information is needed, both for production in nurseries and for potential application in direct seeding (Pérez et al. 2017; Pérez et al. 2019a; Pérez et al. 2019b). Therefore, the objective of this study was to test the effectiveness of four pregerminative treatments in seeds of E. ochreata, from the eastern and western extremes of its distribution in Patagonia Argentina, in order to establish the bases for their use in productive restoration. The hypothesis was treatments that have been effective in improving germination of other Ephedraceae (such as soaking, cold-wet, chemical scarification) would be effective for this species, and that seed characteristics such as germination rate, size and weight would vary between the two origins. MATHERIALS AND METHODS Characteristics of Ephedra ochreata Miers The genus Ephedra L., of the family Ephedraceae (Gnetales) includes 60 species distributed in the deserts and arid regions of the world. This is one of the few gymnosperm taxa that has a highly reduced vegetative structure and is adapted to extreme aridity (Ickert-Bond and Wojciechowski, 2004). Ephedra ochreata is known in Argentina as “solupe”, “pico de loro”, “ephedra” or “pichi fruit” and lives in the arid diagonal bioclimatic entity of Argentina (Gandullo et al., 2004, Martínez, 2013). This species is distributed almost exclusively in Argentina; the only records outside the country are of isolated specimens in a single collection area in Chile (Saldivia et al., 2008). The species has a shrub habit, is rhizomatous, perennial, and can reach up to 1.5 m in height. The stems are photosynthetic, 1.5 to 3 mm in diameter, their leaves are arranged in whorls on the stems and are persistent, but they are reduced to small nonphotosynthetic scales. The species is dioecious and the female strobili are red when ripe, fleshy, 8 to 10 mm long and typically have three seeds covered by bracts (Hunziker, 1998). In Patagonia it flowers at the beginning of October and begins to bear fruit at the end of November (LADYOT, 2017) (Figure 1). RODRÍGUEZ-ARAUJO et al. 619 AGROCIENCIA, 16 de mayo - 30 de junio, 2019 en los tallos y son persistentes, pero están reducidas a escamas pequeñas no fotosintéticas. Es dioica y los estróbilos femeninos son rojos al madurar, carnosos, de 8 a 10 mm de largo y típicamente tienen tres semillas cubiertas por las brácteas (Hunziker, 1998). En la Patagonia florece a principios de octubre y comienza a fructificar a fines de noviembre (LADYOT, 2017) (Figura 1). Recolección y caracterización de semillas Las semillas se recolectaron en dos sitios: MN- cercanías a la localidad de Añelo (Departamento Añelo, Neuquén, Argentina), y DC- médanos costeros del Balneario Playas Doradas (Departamento de San Antonio, Río Negro, Argentina). Ambos sitios se ubican en la provincia fitogeográfica del Monte, distrito Austral, región que constituye uno de los territorios más áridos de Argentina (Busso y Fernández, 2017). Los sitios distan entre sí aproximadamente 500 km y representan los extremos oeste-este de la distribución de la especie en la Patagonia (Figura 2). En Seed collection and characterization The seeds were collected in two localities: “Monte Neuquino” (MN), neighborhoods of the town of Añelo (Department Añelo, Neuquén, Argentina), and “Coastal Dunes” (CD), coastal dunes of the Playas Doradas beach (Department of San Antonio, Río Negro, Argentina). Both sites are located in the Monte phytogeographic province, a region that constitutes one of the most arid areas of Argentina (Busso and Fernández, 2017). The sites are approximately 500 km apart and represent the western and eastern extremes of the distribution of the species in Patagonia (Figure 2). In the western site, MN has an average annual temperature of 14.2 ° C and average annual rainfall is 137.2 mm. Maximum rainfall occurs during winter and spring (Busso and Bonvissuto, 2009). In the eastern site, CD, the average annual temperature is 15.4 ° C and the average annual rainfall is 260 mm. Maximum rainfall occurs in the fall (Genchi, 2012). Figura 1. A) Ephedra ochreata, B) estróbilo femenino, C) semillas, D) estróbilo femenino maduro, E) E. ochreata con estróbilos maduros, y F) estróbilo masculino. Figure 1. A) Ephedra ochreata bush in the field , B) female strobilus, C) seeds, D) mature female strobilus, E) E. ochreata with mature strobili, and F) male strobili. 620 VOLUMEN 53, NÚMERO 4 GERMINACIÓN DE Ephedra ochreata Miers PARA LA RESTAURACIÓN DE AMBIENTES ÁRIDOS EN ARGENTINA Figura 2. Ubicación de los sitios de recolección de semillas en las provincias de Neuquén y Río Negro, Argentina (en negro en el mapa pequeño). MN: Monte Neuquino; DC: Dunas Costeras. Sistema de referencia: coordenadas planas Gauss-Krüger, Posgar 94 faja 2. Figure 2. Location of seed collection sites in the provinces of Neuquén and Río Negro, Argentina (provinces shaded black in the inset map). MN: Monte Neuquino; CD: Coastal Dunes. Reference system: flat coordinates Gauss-Krüger, Posgar 94 strip 2. el Monte Austral Neuquino la temperatura media anual es 14.2 °C y la precipitación media anual es 137.2 mm. Las precipitaciones máximas ocurren durante invierno y primavera (Busso y Bonvissuto, 2009). En las Dunas Costeras la temperatura media anual es 15.4 °C y la precipitación media anual es 260 mm. Las precipitaciones máximas ocurren en el otoño. La recolección se realizó directamente de las plantas alcanzaron la madurez (diciembre de 2012 en MN y enero de 2014 en DC). Los criterios usados fueron los propuestos por Gold et al. (2004): recolectar frutos provenientes de al menos 30 plantas y no más del 20 % de los frutos maduros al momento de la recolección, con la finalidad de no afectar la planta al sustraer un alto número de semillas, así como asegurar una variabilidad genética representativa. Por ser una especie rizomatosa se eligieron las unidades de vegetación típicas del ecosistema (“parches de vegetación”, Busso y Bonvissuto, 2009) distanciados por al menos 30 m entre sí. Las semillas se secaron a temperatura ambiente, Cones were harvested directly from the plants when they reached maturity (December 2012 in MN and January 2014 in CD). The criteria used were those proposed by Gold et al. (2004): we collected fruits from at least 30 plants and no more than 20% of the ripe fruits at the time of harvest; by following these guidelines we avoided affecting the plant by extracting a large number of seeds and ensured that the sample was representative of the genetic variability. As a rhizomatous species, the vegetation units typical of the ecosystem (“vegetation patches” Busso and Bonvissuto, 2009) were chosen, spaced at least 30 m apart. The seeds were dried at 20 °C and cleaned by hand, discarding damaged or empty seeds. Once conditioned, they were stored in paper envelopes in the Banco del Árido germplasm bank (Rodríguez et al., 2015) until germination tests (five months for MN seeds and one month for CD seeds). Ten batches of 100 seeds from each provenance were weighed using a Traveler® balance (model TA 302) to the nearest 0.01 g. The length (mm), RODRÍGUEZ-ARAUJO et al. 621 AGROCIENCIA, 16 de mayo - 30 de junio, 2019 se limpiaron con la mano y se descartaron las dañadas o vanas. Una vez acondicionadas se almacenaron en sobres de papel en el banco de germoplasma Banco del Árido (Rodríguez et al., 2015) hasta iniciar las pruebas (cinco meses para las semillas de MN y un mes para las de DC). Luego se obtuvo el peso (g) de 10 lotes de 100 semillas de cada procedencia mediante una balanza marca Traveler® modelo TA 302, con una sensibilidad de 0.01 g. La longitud (mm), anchura (mm) y espesor (mm) se determinaron en 30 semillas con un calibre vernier marca Digital Caliper®, que tiene un rango de medición de 0 a 150 mm. Pruebas de germinación Un experimento distinto se realizó para cada procedencia, peUn experimento distinto se realizó para semillas de cada procedencia, pero se evaluaron los mismos tratamientos: testigo (T) escarificación química durante 5 min (EQ); remojo por 3 d (RE), y 4 frío-húmedo por 7 d (FH). El tratamiento T fue semillas sin tratamiento pregerminativo. En el tratamiento EQ las semillas se sumergieron 5 min en ácido sulfúrico (95-98 %, Laboratorios Cicarelli), la mezcla se agitó periódicamente para que el ácido se mantuviera en contacto con todas las semillas, las cuales se retiraron con un colador, se lavaron con agua corriente, se remojaron el tiempo necesario hasta alcanzar un pH neutro lo que se monitoreó mediante tiras reactivas, y se secaron sobre papel. En el tratamiento RE las semillas se colocaron en una bolsa de tela porosa, se sumergieron en agua en un frasco de vidrio y se cambió el agua cada 12 h durante 3 d. En el tratamiento FH se colocó una bandeja de poliestireno expandido sobre una capa de algodón cubierta con servilletas de papel humedecida con agua, sobre esta capa se distribuyeron las semillas, se cubrieron con una segunda capa de algodón y papel húmedos y otra bandeja, y se introdujo a una heladera a 4 °C por 7 d. Después de los tratamientos pregerminativos, las semillas se colocaron en cajas Petri con un disco de papel de filtro humedecido y se llevaron a una cámara de germinación marca Servicios Mecatrónicos® con condiciones controladas. La temperatura mínima fue 10 °C ± 1 °C por 12 h en oscuridad y la máxima fue 20 °C ± 1 °C por 12 h, correspondientes al periodo de luz. Estas características representan las condiciones en las que se encontrarían las semillas durante la germinación de otoño (Páez et al., 2005). La germinación se evaluó cada 2 d durante 42 d y el criterio de germinación fue la emergencia de la radícula. Para evaluar la respuesta de las semillas a los tratamientos pregerminativos se determinó el porcentaje de germinación (PG) al final de los 42 d de prueba, y el tiempo medio de germinación (TMG) en días para cada tratamiento, según la ecuación de Ranal y Santana (2006): 622 VOLUMEN 53, NÚMERO 4 width (mm) and thickness (mm) of 30 seeds of each provenance were measured with a Digital Caliper, which has a measurement range of 0 to 150 mm. Germination tests Seeds from each location were tested in a different experiment, but with the same treatments: control (C); chemical scarification for 5 min (CE); soaking for 3 d (SO), and cold-wet for 7 d (CW). Treatment C was seeds with no pregerminative treatment. In the CE treatment, the seeds were immersed for 5 min in sulfuric acid (95-98 %, Cicarelli Laboratories), the mixture was agitated periodically so that the acid remained in contact with all the seeds, the seeds were removed with a strainer, washed with running water, soaked in water as long as necessary to reach a neutral pH (monitored using test strips), and dried on paper. In the SO treatment, the seeds were placed in a porous cloth bag, immersed in water in a glass jar and the water changed every 12 h for a period of 3 d. In the CW treatment, an expanded polystyrene tray was lined with a layer of cotton covered with paper napkins moistened with water, seeds were distributed in a single layer, and covered with a second layer of wet cotton and paper, and another tray. The trays were placed in a refrigerator at 4 °C for 7 d. After the pregerminative treatments, the seeds were placed in Petri dishes lined with a moistened filter paper disc and placed in a Mechatronics Services® brand germination chamber with controlled conditions. The minimum temperature was 10 °C ± 1 °C for 12 h in darkness and the maximum temperature was 20 °C ± 1 °C for 12 h, corresponding to the light period. These characteristics are similar to the conditions in which the seeds would be found during the autumn germination (Páez et al., 2005). Germination was evaluated every 2 d for 42 d; the criterion for germination was the emergence of the radicle. To evaluate the response of the seeds to the pregerminative treatments, the germination percentage (GP) was determined at the end of the 42 d test, and the mean germination time (AGT) in days for each treatment, according to the Ranal and Santana equation (2006): ∑ TMG = ∑ n i =1 n i =1 f i ⋅ xi xi where AGT: is the average number of days it takes for a single seed to germinate, ƒi: is the number of days elapsed since the start of the germination test, and xi: is the number of seeds that germinated within consecutive time intervals. GERMINACIÓN DE Ephedra ochreata Miers PARA LA RESTAURACIÓN DE AMBIENTES ÁRIDOS EN ARGENTINA ∑ TMG = ∑ n i =1 n i =1 f i ⋅ xi xi donde TMG: indica el número promedio de días que tarda una única semilla en germinar, ƒi: es el número de días transcurridos desde el inicio de la prueba de germinación, y xi: es el número de semillas que germinaron dentro de intervalos de tiempo consecutivos. El diseño experimental fue completamente aleatorizado con tres tratamientos pregerminativos por procedencia y un testigo, cada uno con tres repeticiones de 30 semillas tomadas al azar. La unidad experimental fue cada semilla. Los datos de tamaño, peso y PG de las semillas de las dos procedencias y el TMG de las semillas de Dunas Costeras se analizaron con un análisis de varianza, luego de corroborar que los datos cumplieran con los supuestos de normalidad (prueba de Shapiro-Wilks modificada) y homogeneidad de varianzas (prueba de Levene). La diferencia entre medias se analizó con la prueba de Tukey (p£0.05). El TMG de las semillas de Monte Neuquino se analizó con el test no paramétrico de Kruskal-Wallis ya que no se cumplió el supuesto de homogeneidad de la varianza. El análisis estadístico se realizó con INFOSTAT versión 2014 (Di Rienzo et al., 2014) con un nivel de significancia del 0.05. RESULTADOS Y DISCUSIÓN Tamaño y peso de las semillas Las semillas provenientes del Monte Neuquino resultaron en promedio más largas, anchas y pesadas que las de Dunas Costeras, pero similares estadísticamente en grosor (Cuadro 1). En otras especies se han descrito diferencias en el tamaño de las semillas (lbrahim et al., 1997; Dangasuk et al., 1997; Loha et al., 2006; Hathurusingha et al., 2011) y en la capacidad germinativa (Loha et al., 2006; Rawat y Bakshi, 2011) dependiendo de la procedencia. Estas diferencias pueden deberse a la influencia de la variabilidad en las condiciones ambientales y genéticas de las procedencias, en las características las semillas (Ibrahim et al., 1997), lo cual daría lugar a la formación de ecotipos localmente adaptados con óptimo desarrollo y límites de tolerancia a las condiciones de cada lugar (Begon et al., 2006). Además, la variabilidad climática puede afectar la adquisición de nutrientes y determinar la producción de semillas con mayor o menor almacenamiento de The experimental design was completely randomized with three pregerminative treatments and one control for each seed origin, each with three repetitions of 30 seeds taken at random. The experimental unit was the seed. The data on size and weight of the seeds were analyzed with a t test. The GP of the seeds of the two provenances and the AGT of the Coastal Dune seeds were analyzed using an analysis of variance (ANOVA), after corroborating that the data fulfilled the assumptions of normality (modified Shapiro-Wilks test) and homogeneity of variances (Levene test). Differences between means were analyzed with the Tukey test (p£0.05). The AGT of Monte Neuquino seeds was analyzed with the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test, since the assumption of variance homogeneity was not met. The statistical analysis was performed with INFOSTAT version 2014 (Di Rienzo et al., 2014) with the level of significance of 0.05. RESULTS AND DISCUSION Size and weight of the seeds Seeds from Monte Neuquino were on average longer, wider and heavier than those from Coastal Dunes, but statistically similar in thickness (Table 1). Differences have been reported in several species among geographic locations in seed size (lbrahim et al., 1997; Dangasuk et al., 1997; Loha et al., 2006; Hathurusingha et al., 2011), as well as germination rates (Loha et al., 2006; Rawat and Bakshi, 2011). These differences may be due to the influence of the variability on environmental and genetic conditions Cuadro 1. Dimensiones y peso de las semillas (media ± DE) de Ephedra ochreata provenientes de Monte Neuquino (MN) y Dunas Costeras (DC). Table 1. Dimensions and weight of seeds (average ± SD) of Ephedra ochreata from Monte Neuquino (MN) and Coastal dunes (CD). Variable Largo (mm) Ancho (mm) Grosor (mm) Peso 100 semillas (g) N 30 30 30 10 MN Sitio 7.37 ± 0.58a 3.84 ± 0.30a 2.05 ± 0.18a 1.94 ± 0.04a DC 6.44 ± 0.50b 3.26 ± 0.37b 2.00 ± 0.24a 1.32 ± 0.05b a,b: Medias con letra diferente en una hilera son estadísticamente diferentes (p£0.05) v Different letters in a row indicate statistically significant differences (p£0.05). RODRÍGUEZ-ARAUJO et al. 623 AGROCIENCIA, 16 de mayo - 30 de junio, 2019 reserva (Walck et al., 2011). En ambientes mediterráneos se debe considerar que las plántulas de especies con semillas más grandes tienen una mayor supervivencia en condiciones naturales, lo cual puede estar relacionado con una mayor dedicación de biomasa a raíces para una mayor adquisición de recursos (Lloret et al., 1999). Los resultados de nuestro estudio son importantes para el uso de semillas de esta especie en proyectos de restauración porque el peso de las semillas es crucial en el tamaño que alcanzarán las plántulas en las primeras etapas de su crecimiento (Villar et al., 2004), y las diferencias entre las semillas de dos procedencias podrían indicar que corresponden a dos ecotipos diferentes con adaptaciones particulares a las condiciones climáticas propias de los extremos este y oeste de la distribución. Porcentaje y tiempo medio de germinación La germinación fue muy alta (> 80 %) para todos los tratamientos en las dos procedencias. No se encontraron diferencias en los porcentajes de germinación entre los tratamientos pregerminativos. Sin embargo, las semillas provenientes del Monte Neuquino tuvieron mayor germinación que las de Dunas Costeras con porcentajes promedio de 95.11 % ± 2.78 y 85.61 % ± 6.21, respectivamente (Figura 3 A y B). Baskin y Baskin (2014) mencionan la latencia fisiológica en especies del género Ephedra y la necesidad de aplicar tratamientos de estratificación fría. Si bien nuestros resultados muestran que el tratamiento frío-húmedo no produce diferencias respecto de los demás tratamientos, es posible que el periodo de almacenamiento a bajas temperaturas (4 °C) pudo haber propiciado la germinación. La alternancia de temperaturas (10-20 °C) usadas en nuestro estudio parecen ser óptimas para E. ochreata ya que se alcanzaron porcentajes altos de germinación. Para la especie norteamericana E. viridis, Young et al. (1977) también reportan un óptimo de germinación (7787 %) con alternancia de temperaturas frías (2-5 °C) y cálidas (15-25 °C). Sin embargo otras especies del genero Ephedra requieren temperatura constante como E. nevadensis cuya germinación es mayor (63-78 %) en un rango de temperaturas constantes entre 5 y 20 °C (Young et al., 1977), y E. alata cuya temperatura óptima de germinación es 20 °C (Derbel et al., 2010). Las temperaturas óptimas de germinación en las plantas del desierto corresponden con la temperatura de su 624 VOLUMEN 53, NÚMERO 4 upon seeds characteristics (Ibrahim et al., 1997), which would lead to the formation of locally adapted ecotypes with optimum development depending on the limiting environmental conditions of each place (Begon et al., 2006). In addition, climate variability can affect the acquisition of nutrients and determine the production of seeds with more or less reserve storage (Walck et al., 2011). In Mediterranean environments, it must be taken into account that, seedlings of species with larger seeds have greater survival under natural conditions, which may be related to a greater allocation of biomass to root, in order to reach a higher resources acquisition (Lloret et al., 1999). The results of our study are important for the use of seeds of this species in restoration projects because the differences between seeds from the two procedences could indicate that they correspond to two different ecotypes with particular adaptations to the climatic conditions typical of the extreme east and west of the species’ geographical distribution. Germination percentage and average germination time Germination was very high (> 80 %) for all treatments from both sites of origin. No differences were found in the percentages of germination among the pre-germination treatments. However, the seeds from Monte Neuquino had higher germination than those from Coastal Dunes with average percentages of 95.11 % ± 2.78 and 85.61 % ± 6.21, respectively (Figure 3 A and B). Baskin and Baskin (2014) have mentioned physiological dormancy in species of the genus Ephedra and the need to apply cold stratification treatments. Although our results show that the cold-wet treatment did not increase germination percentage compared to the other treatments, it is possible that the storage period at low temperatures (4 °C) prior to the experimental treatments could have favored germination in all of the groups (i.e. the storage conditions applied to all seeds used in the experiment between collection and the germination experiment effectively acted as a cold treatment). The alternation of temperatures (10-20 °C) used in our study seem to be optimal for E. ochreata since high percentages of germination were reached. For the North American species E. viridis, Young et al. (1977) also report optimal germination (77-87 %) GERMINACIÓN DE Ephedra ochreata Miers PARA LA RESTAURACIÓN DE AMBIENTES ÁRIDOS EN ARGENTINA 100 a MN a a a 120 A Germinación (%) Germinación (%) 120 80 60 40 20 T RE FH Tratamiento TMG (días) 20 a a a B 60 40 bc 0 EQ MN 15 c ab a 5 T RE FH Tratamiento 20 C 10 0 80 a 20 TMG (días) 0 100 CD 15 EQ DC D bc c 10 a ab 5 T RE FH Tratamiento EQ 0 T RE FH Tratamiento EQ Figura 3. Porcentaje de germinación (A y B) y tiempo medio de germinación, TMG (T y D) de Ephedra ochreata por procedencia (MN: Monte Neuquino; DC: Dunas Costeras) según tratamiento (T: testigo; RE: remojo durante 3 d; FH: estratificación húmeda durante 7 d; EQ: escarificación química durante 5 min). Medias con letra diferente en un renglón son estadísticamente diferentes (p£0.05). Figure 3. Germination percentage (A and B) and average germination time, AGT (C and D) of Ephedra ochreat from Monte Neuquino (MN) and Coastal Dunes (CD) according to treatments (C: control; SO: soaking for 3 d; CW: wet stratification for 7 d; CE: chemical scarification for 5 min). Means with different letter are significantly different (p£0.05). normal desarrollo (Batanouny y Zieglers, 1971). Los resultados de nuestro estudio indican que la ventana temporal óptima para germinación de esta especie en la naturaleza ocurre entre el otoño, el invierno y los primeros periodos de la primavera (abril-septiembre). No se observaron diferencias en tiempo medio de germinación de las semillas de E. ochreata dependiendo de la procedencia; sin embargo, para cada procedencia hubo diferencias según el tratamiento pregerminativo. Las semillas provenientes del Monte Neuquino tuvieron menor TMG con el tratamiento FH (5.55 ± 0.49 d), mientras que la respuesta más lenta se observó con el tratamiento RE (13.01 ± 1.70 d). Las semillas de Dunas Costeras presentaron menor TMG con los tratamientos FH (9.31 ± 1.24 d) y RE (9.25 ± 0.46 d) y mayor en testigo (13.81 ± 2.29) (Figura 3 C y D). with alternating cold (2-5 °C) and warm (15-25 °C) temperatures. However, other species of the genus Ephedra require constant temperature; for example E. nevadensis has its highest germination rates (6378 %) at a constant temperature range between 5 and 20 °C (Young et al., 1977), and E. alata’s optimal temperature for germination is 20 °C (Derbel et al., 2010). The optimal germination temperatures in desert plants correspond to the temperature of their normal development (Batanouny and Zieglers, 1971). The results of our study indicate that the optimal “temporal window” for germination of this species in nature occurs between autumn, winter and the first periods of spring in the southern hemisphere (april-september). No differences were observed in the average germination time of E. ochreata depending on RODRÍGUEZ-ARAUJO et al. 625 AGROCIENCIA, 16 de mayo - 30 de junio, 2019 Para las semillas provenientes del Monte Neuquino el tratamiento FH produjo la mayor cantidad de semillas germinadas (98.9 %) a los 14 d (Figura 4). Esto coincide con resultados en pruebas de laboratorio con E. viridis y E. nevadensis, donde la máxima germinación (≈ 60 % sin tratamiento) se alcanzó a los 14 d y 10 d, respectivamente (Young et al., 1977; Anderson, 2006). En las semillas de Dunas Costeras todos los tratamientos pregerminativos y el testigo tuvieron germinación similar, aunque el testigo exhibió mayor lentitud en la respuesta (Figura 4). El tratamiento mediante RE produjo una germinación más rápida en las semillas de Dunas Costeras, mientras que en las de Monte Neuquino la respuesta fue más provenance; however, for each seed origin there were differences among pre-germination treatments. The seeds from Monte Neuquino had its lowest average germination time under the CW treatment (5.55 ± 0.49 d), while the longest germination time was under the SO treatment (13.01 ± 1.70 d). The seeds of Coastal Dunes presented shorter germination time under the treatments CW (9.31 ± 1.24 d) and SO (9.25 ± 0.46 d) and longer time to germination under the control treatment (13.81 ± 2.29) (Figure 3C, 3D) For the seeds from Monte Neuquino, the CW treatment produced the highest percentage of germinated seeds (98.9 %) by day 14 (Figure 4A). MN 100 A Germinación (%) 80 60 C RE FH EQ 40 20 0 0 2 4 7 9 11 14 16 18 21 23 25 28 30 32 35 37 39 42 Tiempo del experimento (d) B DC 100 Germinación (%) 80 60 C RE FH EQ 40 20 0 0 2 4 7 9 11 14 16 18 21 23 25 28 30 32 35 37 39 42 Tiempo del experimento (d) Figura 4. Curvas de germinación de Ephedra ochreata por procedencia (MN: Monte Neuquino; DC: Dunas Costeras) según tratamiento (T: testigo; RE: remojo durante 3 d; FH: estratificación húmeda durante 7 d; EQ: escarificación química durante 5 min). Figure 4. Germination curves of Ephedra ochreata by provenance (A: Monte Neuquino, B: Coastal Dunes) according to treatment (C: control, SO: soaking for 3 d, CW: wet stratification for 7 d, CE: chemical scarification for 5 min). 626 VOLUMEN 53, NÚMERO 4 GERMINACIÓN DE Ephedra ochreata Miers PARA LA RESTAURACIÓN DE AMBIENTES ÁRIDOS EN ARGENTINA lenta con menor porcentaje de germinación. Como ya se mencionó, las diferencias entre las procedencias pueden deberse a que pertenecen a ecotipos distintos con rasgos morfológicos y requerimientos pregerminativos particulares. A diferencia de lo mencionado para las semillas de Monte Neuquino, la especie nativa de China E. sinica, presentó mayor germinación (79.9 %) con 12 h de remojo respecto de las semillas sin remojo (44 %), lo cual indicó la presencia de inhibidores químicos en las semillas (Seqinbateer et al., 2009). Para el género Atriplex también se ha descrito que los tratamientos pregerminativos efectivos difieren entre especies (Meyer, 2008). CONCLUSIONES Ephedra ochreata, de ambas procedencias, tiene aptitud para restauración ecológica por su germinación alta y homogénea, lo que facilita su producción en viveros. Las semillas producidas y dispersadas por los plantines reintroducidos a campo propiciarían la regeneración natural, ya que germinan sin tratamiento pregerminativo. Además E. ochreata tiene buena aptitud para restauración en gran escala porque se establecería en campo a partir de la siembra directa de semillas durante otoño, invierno y comienzos de primavera como se ha probado para otras especies en el monte austral. La germinación de E. ochreata no requiere escarificación química para su germinación, por lo cual sería producida por pobladores locales en los viveros comunitarios de plantas nativas en la región y la siembra directa. Las diferencias en tamaños y peso, así como en las respuestas de las semillas a los tratamientos pregerminativos según la procedencia, muestran la importancia de registrar con detalle el origen de las semillas y estudiar las relaciones de los rasgos con el crecimiento y supervivencia de los plantines en los proyectos de restauración ecológica. Este estudio da las bases para evaluar el uso de esta especie en restauración ecológica y productiva de zonas desertificadas de la Patagonia, pero se debe avanzar en investigaciones sobre producción de plántulas de calidad en vivero, sobrevivencia en campo y efectividad de la siembra directa. AGRADECIMIENTOS Agradecemos al Proyecto de Investigación 04/U007, a la Fundación de la Universidad Nacional del Comahue para el De- This coincides with results in laboratory testswith E. viridis and E. nevadensis, where maximum germination (≈ 60% without treatment) was reached at 14 d and 10 d, respectively (Young et al., 1977; Anderson, 2006). In the seeds of Coastal Dunes, all the pre-germination treatments and the control had similar germination rates, but the average germination time was longer under the control treatment (Figure 4B). The SO treatment produced more rapid germination in the seeds of Coastal Dunes, while in those of Monte Neuquino the response was slower with lower percentage of germination. As already mentioned, the differences between the seeds of different origins may be due to the fact that they belong to different ecotypes with morphological features and particular pre-germination requirements. Unlike what was mentioned for Monte Neuquino seeds, the species E. sinica, from China, presented higher germination (79.9 %) with 12 h of soaking compared to seeds without soaking (44 %), which indicated the presence of chemical inhibitors in seeds (Seqinbateer et al., 2009). For species of the genus Atriplex the effectiveness of different pre-germination treatments differs between species (Meyer, 2008). CONCLUSIONS It is important to consider that germination issues are not only important for nursery production; seeds of native species that germinate quickly and easily may have a better chance of becoming wellestablished. In addition, these seeds produced and dispersed from seedlings planted in the field would favor natural regeneration, since they germinate without pre-germination treatment. Ephedra ochreata, from both provenances, showed aptitude for ecological restoration due to its high and homogeneous germination without pretreatments. In addition, E. ochreata could potentially establish in the field from direct seeding during autumn, winter, and early spring of the southern hemisphere. The lack of need for pre-germination treatments or the use of a simple pre-treatment such as cold-wet for germination make it easier for the local residents of arid lands to cultivate this species in nurseries for outplantings or carry out direct seeding in the field. The differences in size and weight, as well as in the responses of the seeds to the pre-germination treatments according to the origin, show the importance of recording in detail the origin of the RODRÍGUEZ-ARAUJO et al. 627 AGROCIENCIA, 16 de mayo - 30 de junio, 2019 sarrollo Regional (FUNYDER) y a la Universidad Nacional del Sur que a través de acuerdos de colaboración proporcionaron el apoyo financiero para el trabajo de campo. A los voluntarios y a los colaboradores de la comunidad de Playas Doradas que participaron en trabajo de campo. Parte de este estudio se desarrolló como parte de la tesis doctoral de M. Emilia R. Araujo en el marco de una beca de doctorado del CONICET. LITERATURA CITADA Anderson, M. K. 2006. Green Ephedra. Ephedra viridis Cov. USDA NRCS National Plant Data. http://Plant Materials. nrcs.usda.gov (Consulta: septiembre 2017). Baskin, C., and J. Baskin. 2014. Seeds. Ecology, Biogeography, and Evolution of Dormancy and Germination. Academic Press. San Diego, USA. 1,586 p. Batanouny, K. H., and H. Ziegler. 1971. Eco-physiological studies on desert plants. II. Germination of Zygophyllum coccineum L. seeds under different conditions. Oecologia 52-63. Begon, M., C. R. Townsend, and J. L. Harper. 2006. Ecology, from Individuals to Ecosystems. 4a Edition. Blackell Publishing Ltd, Oxford, UK. pp: 5-6. Busso, C. A., and G. L. Bonvissuto. 2009. Structure of vegetation patches in northwestern Patagonia, Argentina. Biodivers. Conserv. 18: 3017-3041. Busso, C. A., and O. A. Fernández. 2017. Arid and semiarid rangelands of Argentina. In: Gaur, M. K., and V. R. Squires (eds). Climate Variability Impacts on Land Use and Livelihoods in Drylands. Springer International Publishing. pp: 261-291. Ceccon, E. 2013. Restauración en Bosques Tropicales Fundamentos Ecológicos Prácticos y Sociales. Díaz de Santos Editorial. México. 288 p. Dangasuk, O. G., P. Seurei, and S. Gudu. 1997. Genetic variation in seed and seedling traits in 12 African provenances of Faidherbia albida (Del.) A. Chev. at Lodwar, Kenya. Agroforest. Syst. 37: 133-141. Derbel, S., B. Touzard, M. A. Triki, and M. Chaieb. 2010. Seed germination responses of the Saharan plant species Ephedra alata ssp. alenda to fungicide seed treatments in the laboratory and the field. Flora 205: 471–474. Di Rienzo J. A., F. Casanoves, M. G. Balzarini, L. Gonzalez, M. Tablada, y C. W. Robledo. 2014. InfoStat versión 2014. Grupo InfoStat, FCA, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina. URL http://www.infostat.com.ar Dregne, H., M. Kassas, and B. Razonov. 1991. A new assessment of the world status of desertification. Desertification Control Bull. 20: 6-18. Gandullo, R., J. Gastiazoro, A. Bünzli, y C. Coscaron Arias. 2004. Flora Típica de las Bardas de Neuquén y sus Alrededores. Petrobras. 246 p. Gold, K., P. León-Lobos, y M. Way. 2004. Manual de Recolección de Semillas de Plantas Silvestres para Conservación a largo Plazo y Restauración Ecológica. Editorial Altamirano. La Serena, Chile. 62 p. Hathurusingha, S., N. Ashwath, and D. Midmore. 2011. Provenance variations in seed-related characters and oil content 628 VOLUMEN 53, NÚMERO 4 seeds and study the relationship between germination, survival and site of origin. This study provides a test of the first of several important criteria for the use of this species in ecological and productive restoration of desertified areas of Patagonia, but progress must be made in researching the quality of seedling production in nurseries, survival in the field and production of edible cones and other potential benefits to the inhabitants of the arid lands. —End of the English version— pppvPPP of Calophyllum inophyllum L. in northern Australia and Sri Lanka. New Forests. 41: 89-94. Hunziker, J. H. 1998. Ephedraceae. In: Correa, M. N. (ed). Flora Patagónica. Colecciones Científicas del Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria (INTA). Buenos Aires (Argentina). Tomo 8. Parte 1: 384-391. Ibrahim, A. M., C. W Fagg, and S. A. Harris. 1997. Seed and seedling variation amongst provenances in Faidherbia albida. For. Ecol. Manage. 97: 197-205. LADYOT (Laboratorio de Desertificación y Ordenamiento Territorial). 2017. Ephedra ochreata. Herbario digital. Instituto Argentino de Investigación en Zonas Áridas (IADIZA). http://www.mendoza-conicet.gob.ar/ladyot/herba_digital/ fichas_especies/solupe.htm (Consulta: septiembre 2017). Lloret, F., C. Casanovas, and J. Peñuelas. 1999. Seedling survival of Mediterranean shrubland species in relation to root: shoot ratio, seed size and water and nitrogen use. Funct. Ecol. 13: 210-216. Loha, A., M. Tigabu, D. Teketay, K. Lundkvis, and A. Fries. 2006. Provenance variation in seed morphometric traits, germination, and seedling growth of Cordia africana Lam. New Forests. 32: 71-86. Martínez C., E. 2013. La diagonal árida argentina: entidad bioclimática. In: Pérez, D. R., A. E. Rovere, y M. E Rodriguez A. (eds). Rehabilitación y Restauración en la Diagonal Árida de la Argentina. Vázquez Mazzini Editores. pp: 14-31. Martínez-Romero, P., y E. Ceccon. 2016. Criterios socio-ecológicos para la selección de especies nativas arbóreas en la restauración productiva de la Selva Baja Caducifolia de Santa Ana del Valle, Oaxaca, México. In: Ceccon, E., y D. R. Pérez (coords). Más allá de la Ecología de la Restauración: Perspectivas Sociales en América Latina y el Caribe. Vázquez Mazzini Editores. Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires. Argentina. pp: 277-292. Mazzonia, E., and M. Vázquez 2009. Desertification in Patagonia. In: Latrubesse, E. (ed). Geomorphology of Natural and Human-induced Disasters in South America. Developments in Earth Surface Processes. Elsevier. pp: 351-377. GERMINACIÓN DE Ephedra ochreata Miers PARA LA RESTAURACIÓN DE AMBIENTES ÁRIDOS EN ARGENTINA Meyer, S. 2008. Chenopodiaceae - Goosefoot family. Atriplex L. Saltbush. In: Bonner, F. T., and R. P. Karrfalt (eds). The Woody Plant Seed Manual. US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service Agriculture Handbook. pp: 727, 283-289. Páez, A., C. A. Busso, O. A. Montenegro, G. D. Rodríguez, and H. D. Giorgetti. 2005. Seed weight variation and its effects on germination in Stipa species. Phyton – Rev. Int. Bot. Exp. 54: 1-14. Pérez, D. R., F. M. Farinaccio, F. M. González, J. L. Lagos, A. Rovere, and M. Díaz. 2011. Rehabilitation and restoration to combat desertification in arid and semi-arid ecosystems of Patagonia. Understanding Desertification and Land Degradation Trends. Proceedings of the UNCCD First Scientific Conference, 22–24 September 2009. Publications Office of the European Union. Luxembourg. pp: 124-125. Pérez, D. R., F. M. González, M. E. Rodríguez A., D. A. Paredes, F. M. Farinaccio, R. Chrobak, and E. Meinardi. 2017. Ecological restoration based on environmental education in arid regions of the Argentinean Patagonia. In: Ceccon, E., and D. R. Pérez (coords). Beyond Restoration Ecology. Social Perspectives in Latin America and Caribbean. Vázquez Mazzini Editores. Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires. Argentina. pp: 43-54. Pérez-Domínguez, R., E. Jurado, M. A. González-Tagle, J. Flores, O. A. Aguirre-Calderón, y M. Pando-Moreno. 2013. Germinación de especies del matorral espinoso tamaulipeco en un gradiente de altitud. Rev. Mex. Cien. Forest. 4: 156163. Ranal, M. A. and D. G. Santana. 2006. How and why to measure the germination process? Braz. J. Bot. 29: 1-11. Rapoport, E. H., E. H. Sanz, y A. H. Ladio. 2011. Plantas Nativas Comestibles de la Patagonia Andina Argentino-Chilena. Parte II. Ediciones Imaginaria. San Carlos de Bariloche, Argentina. 81 p. Rawat, K., and M. Bakshi. 2011. Provenance variation in cone, seed and seedling characteristics in natural populations of Pinus wallichiana AB Jacks (Blue Pine) in India. Ann. For. Res. 54: 39-55. Reynolds J. F., F. T. Maestre, E. Huber-Sannwald, J. Herrick, y P. R. Kemp. 2005. Aspectos socioeconómicos y biofísicos de la desertificación. Ecosistemas 14: 3-21 Reynolds, J. F., D. M. Stafford Smith, E. F. Lambin, B. L. Turner II, M. Mortimore, S. P. J. Batterbury, T. E. Downing, H. Dowlatabadi, R. J. Fernández, J. E. Herrick, E. HuberSannwald, H. Jiang, R. Leemans, T. Lynam, F. T. Maestre, M. Ayarza, and B. Walker. 2007. Global desertification: Building a science for dryland development. Science 316: 847-851. Ricco, R. A., V. M. Vai, G. A. Sena, M. L. Wagner, y A. A. Gurni. 2003. Taninos condensados de Ephedra ochreata Miers (Ephedraceae). Acta Farm. Bonaerense 22: 33-38. Rodríguez A., M. E., N. M. Turuelo, y D. R. Pérez. 2015. Banco de semillas de especies nativas de Monte y Payunia para restauración ecológica. Multequina 24: 75-82. Safriel, U., and Z. Adeel. 2005. Dryland systems. In: Hassan, R., R. Scholes and N. Ash (eds). Ecosystems and Human Wellbeing: Current State and Trends: Findings of the Condition and Trends Working Group. Island Press, Washington. pp: 623-662. Saldivia, P., L. Faúndez, y G. Rojas. 2008. Ephedra ochreata (Ephedraceae), nuevo registro para la flora vascular de Chile, en la región de Aisén. Noticiario Mensual Museo Nacional de Historia Natural 360: 4-7. Seqinbateer, A., X. Khasbagan, B. Wurina, and X. J. Wei. 2009. Study on physiological characteristics of seed germination of Ephedra sinica. J. Chin. Medic. Mat. 32: 656-659. Villar, R., J. Ruiz-Robleto, J. L. Quero, H. Poorter, F. Valladares, y T. Marañón. 2004. Tasas de crecimiento en especies leñosas: aspectos funcionales e implicaciones ecológicas. In: Ecología del Bosque Mediterráneo en un Mundo Cambiante. Valladares, F. Ministerio de Medio Ambiente. EGRAF, S. A. Madrid. pp: 191-227. Walck, J. L., S. N. Hidayati, K. W. Dixon, K. E. N. Thompson, and P. Poschlod. 2011. Climate change and plant regeneration from seed. Global Change Biol. 17: 2145-2161. Williams, W., O. Cook, and B. Kay. 1974. Germination of native desert shrubs. Calif. Agric. 28: 13-13. Young, J. A., R. A. Evans, and B. L. Kay. 1977. Ephedra seed germination. Agron. J. 69: 209-211. Zika, M., and K. H. Erb. 2009. The global loss of net primary production resulting from human-induced soil degradation in drylands. Ecol. Econ. 69: 310-318. RODRÍGUEZ-ARAUJO et al. 629 AGROCIENCIA, 16 de mayo - 30 de junio, 2019 630 VOLUMEN 53, NÚMERO 4