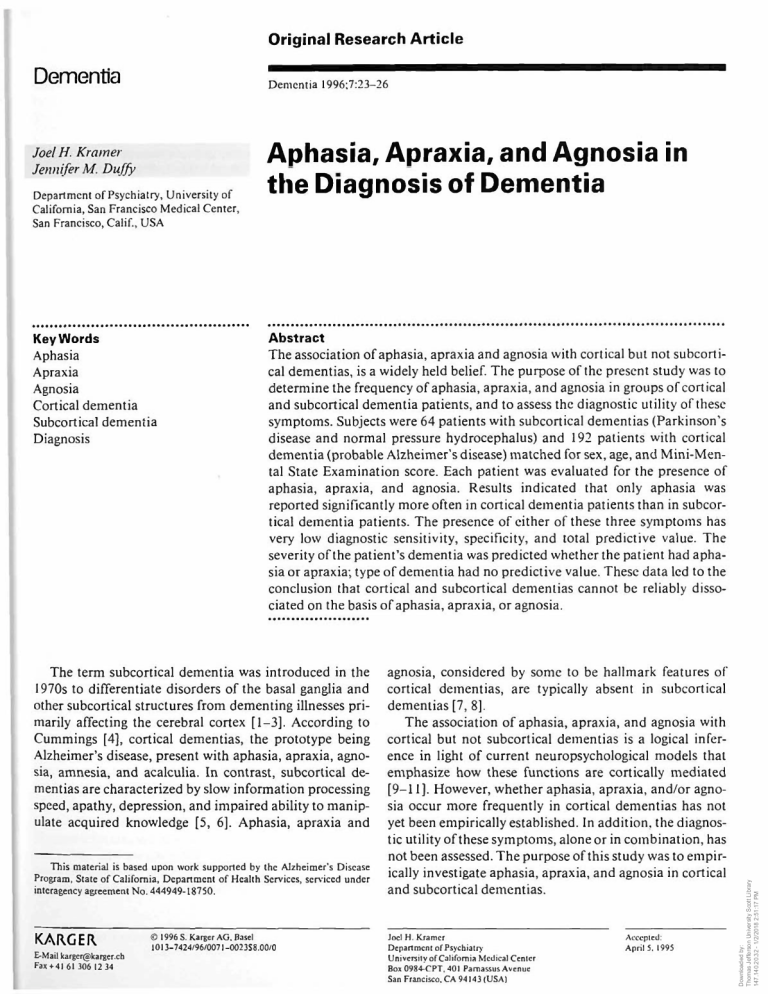

Original Research Article Dementia Dementia 1996;7:23-26 Aphasia, Apraxia, and Agnosia in , „ . Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Francisco Medical Center, San Francisco, Calif., USA tllC D lS g n O S I S KeyVUords Abstract Aphasia Apraxia Agnosia Cortical dementia Subcortical dementia Diagnosis The association of aphasia, apraxia and agnosia with cortical but not subcorti­ cal dementias, is a widely held belief. The purpose of the present study was to determine the frequency of aphasia, apraxia, and agnosia in groups of cortical and subcortical dementia patients, and to assess the diagnostic utility of these symptoms. Subjects were 64 patients with subcortical dementias (Parkinson's disease and normal pressure hydrocephalus) and 192 patients with cortical dementia (probable Alzheimer’s disease) matched for sex, age, and Mini-Men­ tal State Examination score. Each patient was evaluated for the presence of aphasia, apraxia, and agnosia. Results indicated that only aphasia was reported significantly more often in cortical dementia patients than in subcor­ tical dementia patients. The presence of either of these three symptoms has very low diagnostic sensitivity, specificity, and total predictive value. The severity of the patient’s dementia was predicted whether the patient had apha­ sia or apraxia; type of dementia had no predictive value. These data led to the conclusion that cortical and subcortical dementias cannot be reliably disso­ ciated on the basis of aphasia, apraxia, or agnosia. The term subcortical dementia was introduced in the 1970s to differentiate disorders of the basal ganglia and other subcortical structures from dementing illnesses pri­ marily affecting the cerebral cortex [1-3]. According to Cummings [4], cortical dementias, the prototype being Alzheimer’s disease, present with aphasia, apraxia, agno­ sia, amnesia, and acalculia. In contrast, subcortical de­ mentias are characterized by slow information processing speed, apathy, depression, and impaired ability to manip­ ulate acquired knowledge [5, 6], Aphasia, apraxia and This material is based upon work supported by the Alzheimer’s Disease Program, State of California, Department of Health Services, serviced under interagency agreement No. 444949-18750. K A R G E R v r u VVJ L i \ E-Mail karger@karger.ch Fax+ 41 61 306 12 34 @ 1996 S. Karger AG. Basel 1013-7424/96/0071 -0023S8.00/0 O f D e m d l t i a agnosia, considered by some to be hallmark features of cortical dementias, are typically absent in subcortical dementias [7, 8]. The association of aphasia, apraxia, and agnosia with cortical but not subcortical dementias is a logical infer­ ence in light of current neuropsychological models that emphasize how these functions are cortically mediated [9-11], However, whether aphasia, apraxia, and/or agno­ sia occur more frequently in cortical dementias has not yet been empirically established. In addition, the diagnos­ tic utility of these symptoms, alone or in combination, has not been assessed. The purpose of this study was to empir­ ically investigate aphasia, apraxia, and agnosia in cortical and subcortical dementias. Joel H. Kramer Department of Psychiatry University of California Medical Center Box 0984-CPT. 401 Parnassus Avenue San Francisco, CA 94143 (USA) Accepted: April 5.1995 Downloaded by: Thomas Jefferson University Scott Library 147.140.20.32 - 1/2/2018 2:51:17 PM joeih . Kramer Jennifer M. Duffy Table 1. Demographic characteristics of sample (mean ± SD) Diagnosis Age MMSE pAD PD NPH 75.73 ±6.79 76.05 ± 7.88 75.00 ±3.54 19.01 ±5.57 19.28 ±6.08 19.62 ±5.12 Table 2. Number of patients displaying aphasia, apraxia, and agnosia Diagnosis Aphasia Apraxia Agnosia pAD PD NPH 55 (35.5) 8(21.1) 1(13.7) 36 (23.7) 6(15.8) 4(5.3) 21 (13.7) 2(33.3) 0 sia. Aphasia was defined as impairment in the patient’s expressive or receptive language. Expressive language deficits included impair­ ments in the patient’s ability to express him- or herself orally or in writing, and could include empty speech, circumlocutions, paraphasic errors, paragrammaticisms, or impairments in repetition, fluency, and intonation. Receptive language deficits were coded whenever the patient’s ability to understand spoken or written verbal material was compromised. Aphasia was not rated as present if the patient’s lan­ guage deficits were attributable to motor output problems (e.g., dysarthria), apraxia of speech, impaired hearing, inattention, or memory impairment. Apraxia was defined as an inability to carry out purposeful, skilled, and voluntary motor acts. Apraxia was not coded when the patient’s inability to execute a movement was considered due to failure to comprehend the command, primary motor impair­ ment, or sensory loss. An agnosia was coded as present whenever the patient displayed an inability to recognize familiar objects or people in the absence of sensory impairment, attentional disorder, or impaired confrontation naming ability. For each patient, aphasia, apraxia, and agnosia were rated as present, absent, or undeter­ mined. Percentage of group for whom data were available and who dis­ played symptom is in parentheses. M ethods Patients Selection Records from 4,320 patients evaluated by the nine State of Cali­ fornia Alzheimer Centers between 1985 and 1991 were reviewed to identify patients with subcortical dementia. Each patient received a comprehensive and multidisciplinary diagnostic evaluation and was assessed on several medical, neuropsychological, psychiatric, and psychosocial variables. Laboratory and neuroimaging studies was routinely performed. The range of diagnoses within this sample was quite broad, and included probable and possible Alzheimer’s disease, psychiatric disorders, frontal lobe syndromes, movement disorders, and treatable medical conditions. Two disorders with primary sub­ cortical involvement were identified: Parkinson’s disease (PD) and normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH). A search through the sample of 4,320 patients located 87 patients with PD and 29 with NPH, for a total of 116 patients with subcortical disorders. From this group, 36 PD patients were excluded because Alzheimer’s disease could not be ruled out as a diagnostic possibility. Thirteen NPH patients were excluded because Alzheimer’s disease was not ruled out, 2 were excluded because of probable cerebrovascular disease, and 1 was excluded because of a history of significant head trauma. Sixty-four patients with subcortical dementia remained in the sample, 51 with PD and 13 with NPH. For each patient with a diagnosis of subcortical dementia, 3 patients with probable Alzheimer’s disease (pAD) were selected, matched on age, sex, and Mini-Mental State Examination score (MMSE) [12], All patients with pAD met ADRDA-NINCDS criteria [13]. Descriptive statistics for each group are summarized in table 1. Procedure Each patient was evaluated by the Alzheimer’s Center’s physician or ncuropsychologist for the presence of aphasia, apraxia and agno­ 24 Dementia 1996;7:23-26 The percentage of patients within each diagnostic group that displayed aphasia, apraxia, and agnosia is pre­ sented in table 2. Group differences in the frequency of each symptom were analyzed with the x2statistic. Only patients for whom the symptom was rated as present or absent were included in the analyses. The first set of analyses compared patients with PD and NPH. No significant differences were found in the frequency of aphasia, apraxia or agnosia between these groups. Data from these two diagnostic categories were therefore combined into a single subcortical dementia group for subsequent analyses. Aphasia was reported significantly more often in pa­ tients with cortical dementia than in patients with subcor­ tical dementia (x2 = 5.01; p < 0.05). Cortical dementia patients were almost twice as likely as subcortical demen­ tia patients to be characterized as aphasic. Despite this significant group difference, the majority of cortical de­ mentia patients (63.3%) were coded as not having apha­ sia. There were no significant group differences in the fre­ quency of apraxia. A trend in the predicted direction was found for the frequency of agnosia (x2= 3.42; p = 06), with agnosia appearing more often in the pAD patients than in the subcortical patients. The diagnostic utility of aphasia, apraxia, and agnosia was assessed several ways. First, patients who had either aphasia, apraxia, or agnosia were given a predicted diag­ nosis of cortical dementia. The accuracy of the predicted Kramer/Duffy Downloaded by: Thomas Jefferson University Scott Library 147.140.20.32 - 1/2/2018 2:51:17 PM Results The results of this study indicate that when welldefined and matched samples of cortical and subcortical dementia patients are compared, there are no significant group differences in the prevalence of apraxia. Aphasia occurred more frequently in the cortical group than in the subcortical group and there was a nonsignificant trend for agnosia to occur more often in the cortical group than in the subcortical group. Although group differences in symptom frequency may occur, information about the presence of aphasia, apraxia, and agnosia contributes very little toward diag­ nosis. The majority of pAD patients had none of the three symptoms, whereas almost a quarter of the subcortical dementia patients displayed at least one of the symptoms. The total predictive value of these ‘cortical dementia’ symptoms was at chance levels. In addition, knowledge about aphasia and agnosia contributed less than 3% of the variance in diagnosis. Finally, aphasia and apraxia were most highly correlated with the overall degree of dementia and, when dementia severity was controlled for, this symptoms were not predictive of dementia type. Current notions about dementias hold that subcortical dementias lack the symptoms of aphasia, apraxia, or agnosia, and that these symptoms are common in patients with cortical dementia. This study, however, argues that this distinction is not empirically supported. Results are consistent with growing evidence that many of the distin­ guishing characteristics used to classify the cortical and subcortical dementias overlap [15, 16]. Other studies have also indicated that significant numbers of demented patients with aphasia, apraxia, or agnosia did not exhibit enough other evidence for the diagnosis of cortical de­ mentia [17, 18]. Huber et al. [ 19] reported aphasia, aprax­ ia, and agnosia in patients who developed PD and whose pathology did not support a diagnosis of pAD. The blur­ red distinctions between cortical and subcortical demen­ tias is consonant with the pathologic overlap between commonly accepted cortical and subcortical disorders. Neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic plaques have been found in demented patients with PD [20, 21] and some researchers have found nigral degenerative changes, in­ cluding Lewy bodies, in patients with pAD [22]. The present study was based on data from nine demen­ tia diagnostic centers. The resulting large sample adds credence to the results and represents a strength of this study. A potential disadvantage of a multicenter database, however, is that despite uniform diagnostic criteria, some variability between centers in how diagnoses were made Aphasia, Apraxia and Agnosia Dementia 1996;7:23-26 25 Downloaded by: Thomas Jefferson University Scott Library 147.140.20.32 - 1/2/2018 2:51:17 PM D iscu ssio n diagnosis was evaluated for sensitivity, specificity, and total predictive value [14]. Sensitivity is the probability that the correct diagnosis is cortical dementia whenever aphasia, apraxia or agnosia are present. Specificity is the probability that the correct diagnosis is subcortical de­ mentia whenever aphasia, apraxia, or agnosia are absent. Finally, total predicted value is the total proportion of patients whose diagnosis is accurately predicted. Predicting a cortical dementia on the basis of aphasia, apraxia, or agnosia being present had a sensitivity of only 45.28%. The majority of pAD patients did not present with aphasia, apraxia, or agnosia. This resulted in most pAD patients misclassified as belonging to the subcortical group. Specificity was also poor (75,47%). Almost a quar­ ter of the subcortical group presented with one of the three ‘cortical’ symptoms. The total predictive value was 52.83%, which is at chance levels. The diagnostic utility of aphasia, apraxia and agnosia was also assessed using multiple regression. The question was framed as follows: What proportion of the variance in diagnosis can be attributed to the presence of aphasia, apraxia, and agnosia. The degree of dementia was con­ trolled for by virtue of the fact that the subcortical and cortical dementia groups were originally matched for MMSE score. Results indicated significant relationships for aphasia (F = 5.71, p < 0.05) and agnosia (F = 4.05, p < 0.05). The proportion of variance explained was quite small, however; approximately 2% for agnosia and 2.7% for aphasia. Apraxia did not contribute a significant pro­ portion of variance in diagnosis (less than 1%). The low predictive value of aphasia, apraxia, and agno­ sia indicated that these symptoms were only weakly asso­ ciated with the cortical vs subcortical locus of the dement­ ing disorder. This findings raised the question of whether these symptoms were more strongly associated with vari­ ables other than diagnosis. To address this issue, multiple regression analyses were carried out to identify patient characteristics that predicted the presence of the three symptoms. MMSE score, sex, and diagnosis were entered into the multiple regression in a stepwise fashion as pre­ dictor variables. None of these patient characteristics pre­ dicted the presence of agnosia. MMSE score explained a significant proportion of the variance for apraxia (F = 5.54; p < 0.05); no other variables contributed to the vari­ ance. For aphasia, MMSE was also the only variable remaining in the regression equation (F = 9.14; p < 0.005). Thus, degree of dementia was significantly correlated with the presence of aphasia and apraxia and, once dementia severity was accounted for, diagnosis did not explain a significant proportion of the variance. cannot be ruled out. Similarly, although a uniform set of operational criteria were used, different centers, and dif­ ferent clinicians within a center, may have had different thresholds for when they coded a patient as having apha­ sia, apraxia, or agnosia. It is unlikely, however, that this variability affected the results of this study. Any variabili­ ty in coding symptoms should have been equally true for both cortical and subcortical syndromes and had little effect on the weak relationship between clinical symptom and dementia subtype. Finally, although this study argues that distinctions between cortical and subcortical dementias cannot be reli­ ably made on the basis of aphasia, apraxia, and agnosia, it is possible that dissociations can be made according to other neuropsychological Findings. Some investigators have pointed to distinctive patterns of memory impair­ ment. Whereas both types of dementia syndromes are associated with impaired immediate recall, pAD patients, relative to subcortical patients, have been found to have more rapid forgetting over time, greater deficits in recog­ nition memory, and a greater tendency to make intrusion errors [23], Clear distinctions have also been reported on measures of nondeclarative memory. Patients with pAD generally show deficits on lexical priming tasks but not motor skill learning [24], whereas patients with Hunting­ ton’s disease show the opposite pattern. Several studies have also reported differences in verbal fluency. Because of their presumed breakdown in semantic structures, pAD patients are even more impaired in their category fluency than in their letter fluency. Subcortical patients, on the other hand, often display the opposite pattern because their underlying impairment is presumed to be one of initiation and retrieval [25,26]. Finally, subcortical syndromes are more strongly associated with deficits in executive functioning, that is, attention, conceptual rea­ soning, and self-regulation [8]. References 26 Dementia 1996;7:23-26 12 Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: ‘Minimental state’. A practical method for grading the cognitive stale of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189-190. 13 McKann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadia E: Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: Report of the N1NCDSADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 1984;34:939-944. 14 Mossman D, Somoza E: Ncuropsychiatric de­ cision making: The role of disorder prevalence in diagnostic testing. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Ncurosci 1991:84-88. 15 Kramer JH, Levin BE, Brandt J, Delis DC: Dif­ ferentiation of Alzheimer’s, Huntington's, and Parkinson's disease patients on the basis of ver­ bal learning characteristics. Neuropsychology 1989;3:111-120. 16 Levin BE, Tomer R, Rey G: Cognitive impair­ ments in Parkinson’s disease. Neurol Clin 1992;10:471-485. 17 Sulkava R, IJaltia M, Paetau A, Wikstrom J, Palo J: Accuracy of clinical diagnosis in prima­ ry degenerative dementia: Correlation with neuropathological findings. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1983;46:9-13. 18 Molsa PK, Paljarvi L, Rinne JO, Rinne UK, Sako E: Validity of clinical diagnosis in demen­ tia: A prospective clinicopathological study. J Neurol, Neurosurg Psychiatry 1985:48:1085— 1090. 19 Huber SJ, Edwin C, Shuttleworth EC, Donald L, Frcidenberg DC: Neuropsychological differ­ ences between the dementias of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson's disease. Arch Neurol 1989:46: 1287-1291. 20 Hakim AM, Mathieson G: Dementia in Par­ kinson's disease; a neuropathologic study. Neu­ rology 1979:29:1209-1214. 21 Boiler F, Passafiume D, Keefe NC, Rogers K, Morrow L, Kim Y: Visuospatial impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Role of perceptual and motor factors. Arch Neurol 1984:41:485-490. 22 Joachim CL, Morris JH, Selkoe DJ: Clinically diagnosed Alzheimer's disease: Autopsy results in 150 cases. Ann Neurol 1988;24:50-56. 23 Massman PJ, Delis DC, Butters N, Levin BE, Salmon DP: Are all subcortical dementias al­ ike? Verbal learning and memory in Parkin­ son's and Huntington’s disease patients. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 1990;12:729-744. 24 Hcindcl WC, Salmon DP, Shults CW, Walicke PA, Butters N: Neuropsychological evidence for multiple implicit memory systems: A com­ parison of Alzheimer's, Huntington’s, and Par­ kinson’s disease patients. J Neurosci 1989:9: 582-587. 25 Monsch AU, Bondi MW, Butters N, Salmon DP, Katzman R, Thai LJ: Comparison of ver­ bal fluency tasks in the detection of dementia of the Alzheimer type. Arch Neurol 1992:49: 1253-1258. 26 Monsch AU, Bondi MW, Butters N, Paulsen JS, Salmon DP, Bruggcr P. Swenson MR: A comparison of category and letter fluency in Alzheimer’s disease and Huntington’s disease. Neuropsychology 1994;8:25-30. Kramer/DufTy Downloaded by: Thomas Jefferson University Scott Library 147.140.20.32 - 1/2/2018 2:51:17 PM 1 Albert ML, Feldman RG, Willis AG: The ‘sub­ cortical dementia- of progressive supranuclear palsy. J Neurol Ncurosurg Psychiatry 1974;37: 121-130. 2 Cummings JL. Benson DF: Psychological dys­ function accompanying subcortical dementias. AnnuRevMcd 1988:39:53-61. 3 Whitehousc PJ: The concept of subcortical and cortical dementia: Another look. Ann Neurol 1986;19:1-6. 4 Cummings JL: Subcortical dementia. Neuro­ psychology, neuropsychiatry, and pathophysi­ ology. Br J Psychiatry 1986;149:682-697. 5 Cummings JL, Benson DF: Subcortical demen­ tia. Review of an emerging concept. Arch Neu­ rol 1984;41:874-879. 6 Huber SJ, Shultleworlh EC, Paulson GW, Bellchambers MJ, Clapp LE: Cortical vs. subcorti­ cal dementia. Neuropsychological differences. Arch Neurol 1986:43:392-394. 7 Huber SJ, Paulson GW: The concept of subcor­ tical dementia. Am J Psychiatry 1985;142: 1312-1317. 8 Huber SJ, Shuttleworth EC: Neuropsychologi­ cal assessment of subcortical dementia; in Cummings JL (ed): Subcortical Dementia. New York, Oxford University Press, 1990. 9 Benson DF: Aphasia; in Heilman KM, Valenstein EV (eds): Clinical Neuropsychology, ed 3, New York, Oxford Press, 1993. 10 Heilman KM, Gonzalez Rothi LJ: Apraxia; in Heilman KM, Valenstein EV (eds): Clinical Neuropsychology, ed 3. New York, Oxford University Press, 1993. 11 Bauer R: Agnosia; in Heilman KM, Valenstein EV (eds): Clinical Neuropsychology, cd 3. New York, Oxford University Press, 1993.