Religious involvement and dispositional characteristics as predictors of work attitudes and behaviors BAJADO POR JAIRO PUCHE

Anuncio

INFORMATION TO USERS

This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the

text directly from the original or copy submitted.

Thus, some thesis and

dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of

computer printer.

The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy

submitted. Broken or indistinct print colored or poor quality illustrations and

photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment

can adversely affect reproduction.

In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and

there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright

material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion.

Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning

the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to

right in equal sections with small overlaps.

Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced

xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6“ x 9” black and white photographic

prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for

an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order.

Bell & Howell Information and Learning

300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA

UMI’

800-521-0600

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

RELIGIOUS INVOLVEMENT AND DISPOSITIONAL CHARACTERISTICS

AS PREDICTORS OF

WORK ATTITUDES AND BEHAVIORS

by

Tami L. Knotts, B.S., M.B.A.

A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment

of the Requirements for the Degree

Doctor of Business Administration

COLLEGE OF ADMINISTRATION AND BUSINESS

LOUISIANA TECH UNIVERSITY

July 2000

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

UMI Number 9970998

__

_®

UMI

UMI Microform9970998

Copyright 2000 by Bell & Howell Information and Learning Company.

All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against

unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code.

Bell & Howell Information and Learning Company

300 North Zeeb Road

P.O. Box 1346

Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

LOUISIANA TECH UNIVERSITY

THE GRADUATE SCHOOL

August 17. 2000__________

Date

We

hereby

recommend

b y ________________________

that

the dissertation

prepared

under

our

supervision

TamiLeigh Knotts________________________________

entitled______________ Religious Involvement and Dispositional_____________________

_________ Characteristics as Predictors o f W ork Attitudes and Behaviors_____________

be

accepted

in

partial

fulfillment

of

Doctor of Busini

the

requirements

for

the

Degree

of

minBtration

Supervisor o f Dii

O: M U

ition Ri

Head o f Department

Management

Department

Recommendation concurred in:

Advisory Committee

Approvi

Director o f Graduate Studies

Approvej:

Director o f the Graduate School

Dean o f the College

GS Form 13

( 1/00)

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this dissertation was to empirically

examine the effects of

attitudes,

(2)

(1)

religious

dispositions

on

job

involvement on job

attitudes,

religious involvement on workplace behaviors.

and

(3)

This study

also assessed whether job attitudes mediated theeffect of

religious

involvement

interaction

effect

on

of

workplace

religious

behaviors

or

involvement

the

and

dispositional characteristics on workplace behaviors.

Higher

levels

of

religious

involvement

were

hypothesized to lead to more positive work attitudes and

behaviors.

Conservative

and

self-transcendent

values

along with positive well-being were expected to lead to

positive

attitudes

at

work.

The

effect

of

religious

involvement on work behaviors and the interactive effect

of

religious

behaviors

involvement

were

and

hypothesized

dispositions

to

be

on

mediated

by

work

job

attitudes.

The sample for this dissertation was drawn from two

organizations

automotive

including a rehabilitation hospital and an

parts

distributor.

Employee

and

i

Reproduced with permission o f the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

supervisor

questionnaires

were

distributed

in

conjunction

with

payroll checks and were returned through the mail.

Two

waves of questionnaires produced a total of 113 employee

and 22 supervisor surveys.

The response rates were

30

percent for the non-supervisory employees and 55 percent

for the supervisors.

Hierarchical

regression

analysis

and

mediated

regression analysis were employed to test the hypotheses.

The results provided partial support

for the hypotheses.

An extrinsic-personal religious orientation was positively

associated with job

direction

values

involvement

positive

job

involvement.

were

and

negatively

organizational

relationship

involvement,

Stimulation and

was

and

associated

commitment.

found between

an

self-

with

job

Also,

a

benevolence

extrinsic-personal

and

religious

orientation was found to be positively associated with in­

role

and

extra-role

organization.

mediation

behavior

Finally,

effect.

some

An

that

support

benefited

was

found

extrinsic-personal

the

for

a

religious

orientation interacted with both positive affect and life

satisfaction

satisfaction,

to

lessen

turnover

organizational

intentions

commitment,

involvement.

ii

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

through

job

and

job

Managerial implications of these findings along with

contributions to the management literature are discussed.

Suggestions

for

future

research

are

also

academicians.

iii

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

provided

for

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to express my gratitude to everyone who

contributed to the completion of this dissertation.

Dr.

Tim Barnett, my dissertation chairman, deserves a special

thanks.

Dr.

Throughout my doctoral program at Louisiana Tech,

Barnett

has

spent

countless

reviewing and revising my work.

made

the

rewarding

completion

experience.

dissertation

my

(and

red pens!)

His guidance and support

degree

a

I am also

grateful

my

comments

and

suggestions.

A specialthanks also goes to Dr. Inman

for

providing me

with the opportunity

of this

for

their

Tony

to

and

Dr.

Richard,

members, Dr.

meaningful

Inman and

Orlando

committee

of

hours

valuable

to become a part

doctoral program.

In

addition

to the professional

would like to thank my parents,

acknowledgments,

I

Mack and JoNell Knotts,

and the rest of my family for their constant support and

encouragement in all of my endeavors.

Their unconditional

love and belief in me has made my dream of achieving my

doctorate a reality.

iv

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

P age

ABSTRACT ..........................................

i

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS..................................

iv

TABLE OF CONTENTS..................................

v

LIST OF T A B L E S ....................................

ix

LIST OF FIGURES....................................

xi

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION..........................

Definitions of Study Variables................

Religious Variable ......................

Religious Involvement ..............

Dispositional Variables..................

Value T y p e s ........................

Personality ........................

Subjective Well-Being ..............

Attitudinal Variables....................

Job Satisfaction....................

Organizational Commitment ..........

Job Involvement....................

Behavioral Variables ....................

Turnover Intentions ................

Job Performance . . . . .

The Importance of Religious Involvement . . . .

Statement of the Problem......................

Objectives of the S t u d y ......................

Plan of the S t u d y ............................

Research Purpose ........................

Hypotheses Development..................

Religious Involvement and Job

Attitudes..........................

Religious Involvement and Workplace

Behaviors..........................

Dispositions and Job Attitudes. . . .

The Mediating Role of Job Attitudes .

Research Methodology....................

Sample Methodology..................

1

3

3

4

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

7

7

7

3

3

10

12

12

12

I4

v

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

I4

I4

I3

I3

I3

I3

Data Collection Procedures............

Statistical Techniques................

Contributions of the Study......................

Overview of the S t u d y ..........................

CHAPTER 2: REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE................

Theory of Planned Behavior......................

Religion........................................

Western Religions..........................

Christianity..........................

J udaism..............................

Religious Involvement Conceptualizations........

Religiosity................................

Religiousness..............................

Religious Orientation......................

Religious Involvement ..........................

Potential Consequences of Religious Involvement .

Dispositions..............................

Value T y p e s ..........................

Cognitive Dissonance Theory. . . .

Religious Socialization..........

Reinforcement Theory ............

Personality..........................

Subjective Well-Being ................

Job Attitudes..............................

Job Satisfaction......................

Organizational Commitment ............

Job Involvement......................

Workplace Behaviors........................

Absenteeism..........................

Turnover Intentions..................

Job Performance......................

In-role Behavior ................

Extra-role Behavior..............

Unethical Behavior....................

Problems with Research on Religious Involvement .

Unidimensional Approach....................

Multidimensional Approach..................

Potential Outcomes of Dispositions..............

Job Attitudes..............................

Job Satisfaction......................

Organizational Commitment............

Job Involvement......................

Problems with Dispositional Research............

Interactions Between Religious Involvement and

Dispositions....................................

Potential Outcomes of Job Attitudes............

vi

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

16

I*7

I"7

19

20

21

26

27

28

30

31

32

36

37

44

45

46

46

52

53

55

57

61

64

65

66

67

69

69

79

72

72

74

76

79

80

80

81

81

84

87

89

90

92

93

Workplace Behaviors.......................

Absenteeism..........................

Turnover Intentions ..................

Job Performance......................

Unethical Behavior....................

Religious Expression in the Workplace .

Chapter Summary..................................

94

94

98

98

99

100

101

CHAPTER 3: RESEARCH METHODOLOGY...................... 103

Research Hypotheses.............................. 103

Religious Involvement and Job Attitudes. . . 103

Job Satisfaction........................ 105

Organizational Commitment.............. 106

Job Involvement........................ 107

Religious Involvement and Workplace

Behaviors.................................... 108

Turnover Intentions ..................

109

Job Performance........................ Ill

In-role Behavior.................. Ill

Extra-role Behavior................ 113

Dispositions and Job Attitudes.............. 115

Value T y p e s ............................ 115

Subjective Well-Being.................. H 8

The Mediating Role of Job Attitudes.......... 120

Religious Involvement.................. 120

Religious Involvement and Dispositions. 123

Religious involvement and Value

Types............................ 123

Religious involvement and

Subjective Well-Being............ 124

Operationalization of Variables ................

125

Religious Involvement........................ 125

Religiosity and Religiousness ........

126

Religious Orientation.................. 128

Dispositions .............................. 131

Value T y p e s ............................ 132

136

Subjective Well-Being ................

Job Attitudes................................ 141

Job Satisfaction........................ 141

Organizational Commitment ............

143

Job Involvement........................ 145

Workplace Behaviors.......................... 147

Turnover Intentions ..................

147

Job Performance........................ 149

Social Desirability.......................... 152

Research Instrument.......................... 154

Research Design ................................

154

vii

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

Sample Methodology..........................

Data Collection Procedures..................

Statistical Techniques......................

Chapter Summary ................................

154

155

155

157

CHAPTER 4: PRESENTATION OF DATA ANALYSIS.............. 159

Characteristics of the S a m p l e .................... 159

Assessment of Potential Non-Response Bias . . . .

167

Reliability of Measurement Instruments............ 168

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations of Study

Variables........................................ 172

Tests of Hypotheses.............................. 179

HI: Religious Involvement and Job Attitudes. 180

H2a-2c: Religious Involvement and Workplace

Behaviors.................................... 182

H3a-3e: Dispositions and Job Attitudes . . . 185

H4a-4c: The Mediating Role of Job Attitudes. 188

Chapter Summary ................................

191

CHAPTER 5: DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS................ 192

Research Findings................................ 192

Religious Involvement and Job Attitudes. . . 193

Religious Involvement and Workplace

Behaviors.................................... 195

Dispositions and Job Attitudes.............. 197

The Mediating Role of Job Attitudes.......... 200

201

Managerial Implications ........................

Limitations of the Study.......................... 207

Contributions of the Study........................ 208

Suggestions for Future Re se a r c h .................. 210

APPENDIX A ............................................ 213

Research Instrument ............................

214

APPENDIX B ............................................ 222

Employee Cover L e t t e r ............................ 223

APPENDIX C ............................................ 224

Supervisor Cover Letter ........................

225

REFERENCES............................................226

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

LIST OF TABLES

P age

Table 2.1

Similarities and Differences of

Religious Involvement

Conceptualizations.................

33

Table 2.2

Components and Modes of Religiosity

. .

35

Table 2.3

Religious Involvement and

Dispositional Characteristics ........

47

Table 2.4

Instrumental and Terminal Values. . . .

48

Table 2.5

Motivationally Distinct Value Types

50

Table 2.6

Dimensions of Personality.........

Table 2.7

Dimensions of Subjective Well-Being

Table 2.8

Dispositional Characteristics and Job

Attitudes.........................

. .

58

. .

62

82

Table 2.9

Job Attitudes and Workplace Behaviors

Table 3.1

Personal Involvement Inventory....... 127

Table 3.2

Religiosity S c a l e ................... 129

Table 3.3

Intrinsic/Extrinsic-Revised Scale .

Table 3.4

Schwartz Value S u r v e y ...............134

Table 3.5

Satisfaction With Life Scale......... 138

Table 3.6

Positive Affect Negative Affect

Schedule............................ 139

Table 3.7

Global Measure of Job Satisfaction.

ix

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

.

. .

. .

95

130

142

Table 3.8

Organizational Commitment

Questionnaire ........................

144

Table 3.9

Job Involvement S c a l e .................. 146

Table 3.10

Intention to T u r n o v e r...................148

Table 3.11

Job Performance S c a l e ...................151

Table 3.12

Social Desirability S c a l e ...............153

Table 4.1

Sample Characteristics by Company . . .

Table 4.2

Sample Characteristics...................166

Table 4.3

Comparison of Early and Late

Respondents on Demographic and Study

Variables.............................. 169

Table 4.4

Reliability Analysis of Dissertation

Scales.................................. 171

Table 4.5

Descriptive Statistics and

Correlation Coefficients................ 173

Table 4.6

Hierarchical Regression Results:

Religious Involvement and

Dispositional Characteristics ........

181

Hierarchical Regression Results:

Workplace Behaviors ..................

184

Table 4.7

163

Table 4.8

Results of Mediated Regression

Analysis................................ 189

Table 5.1

Summary Table of Results and

Implications............................ 202

x

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

LIST OF FIGURES

Page

Figure 1.1

Theoretical Framework ..............

2

Figure 1.2

Research Process....................

13

Figure 2.1

Theory of Planned Behavior..........

22

Figure 2.2

Individual and Social Determinants.

of Work Quality....................

25

Dimensions and Categories of

Motivationally Distinct Value Types .

51

Research Framework..................

104

Figure 2.3

Figure 3.1

xi

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

This

dissertation

religious

Figure

involvement

1.1# based

behavior

(Ajzen#

investigates

on

in

job

part

the

attitudes

on

the

impact

and

theory

its

effect

involvement

including values,

According

to

planned

1988), represents a useful framework for

potential

religious

behaviors.

of

understanding the relationships of interest.

to

of

on

may

attitudes

also

personality,

Stone-Romero

In addition

and

influence

behavior,

dispositions

and subjective well-being.

and

Stone

(1998),

religion

specifies virtuous characteristics that individuals should

possess

in

attitudes.

appropriate

the

form

of dispositions,

behavior

several

personality,

behavior

and

Furthermore, religion defines for individuals

under

(Stone-Romero & Stone, 1998).

affect

traits,

circumstances

Thus, religion may directly

individual

subjective

particular

factors

well-being,

(Stone-Romero

&

including

values,

attitudes,

Stone,

1

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

and

1998).

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

RKLIQIOOS

INVOLVEMENT

Religiosity

‘Cognition

‘Affect

‘Behavior

IMlflOUMMf

‘Substantive

•Functional

JOB ATTXTUD1S

Religious Orientation

‘Intrinsic

‘Extrinsic

------ j----

Nasenteelsa

Job Satisfaction

Turnover Intentions

Organisational

Ferfonaanoo

Job Invol'

♦ ______

DISPOSITIONS

*In-Role

•Extra-Role

Unethical lehavlor

Rellgloue

■spreselon

Value Types

•Openness to Change

versus Conservation

*3elf-Enhancement

versus SelfTranscendence

Personality

•Extroversion

‘Agreeableness

•Conscientiousness

‘Openness to Experience

‘Neuroticlsm

Subjective Well-Suing

‘Life Satisfaction

•Positive Affect

•Negative Affect

Figure 1.1

Theoretical Framework

3

This chapter presents definitions of study variables

and discusses the importance of religious involvement in

the workplace.

Following this discussion,

the statement

of the problem and objectives of the study are provided.

Finally,

the chapter concludes by outlining the plan of

the study and its important contributions.

Definitions of Study Variables

To provide a common understanding of the terminology

used in this dissertation,

the following section provides

definitions of the major study variables.

Religious Variable

Although there is no generally accepted definition of

religion,

and

it typically

practices

Romero

symbolic

&

associated

Stone,

with

1998).

membership.

individuals

who

necessarily

religious.

alternative

involves

the

being

Religion

Symbolic

simply

definitions

claim

To

of

thoughts,

religious

may

also

membership

a

feelings,

is

religion

differentiate

but

(Stoneencompass

held

are

between

religion,

dissertation focuses on religious involvement.

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

the

by

not

these

present

Religious Involvement

Religious

feelings,

with

and

involvement

behaviors

one's motivation

al.,

1986;

Allport

refers

to

the

associated with

for being

&

religion

religious

Ross,

beliefs,

(Cornwall

1967).

religiosity,

orientation.

and

religiousness,

Religiosity refers

affiliation with a particular

Burnett,

1990).

Generally,

religiosity-cognition,

affect,

approaches to religion.

These

religious

commitment

religion

three

Religiousness, on the other hand,

and

to one's

et

Various

conceptualizations of religious involvement exist.

include

along

to

(McDaniel

concepts

and

&

describe

behavior.

focuses on two separate

One approach involves beliefs and

practices directed towards a higher power while the other

approach

focuses

1997).

Finally,

on existential

religious

concerns

(Pargament,

orientation represents

one's

motivation for being religious, which can be classified as

either

intrinsic

intrinsic

or extrinsic.Individuals

orientation

individuals

with

truly

an extrinsic

live

Because

each of these

while

simply

use

(Allport & Ross,

terms describes

degree what it means to be religious,

an

religion

orientation

religion to satisfy their basic needs

1967).

with

this

to

dissertation

uses a collective term called religious involvement.

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

some

5

Dispositional Variables

For the purposes of this dissertation,

dispositions

represent psychological tendencies to react in a certain

way

(House,

Shane,

& Herold,

1996).

Examples

include

value types, personality, and subjective well-being.

Value Typas

A personal value is an enduring belief about present

conduct or future existence

(Rokeach, 1968) while a value

type represents an enduring belief about a primary goal.

According to Schwartz and Bilsky (1987, 1990), ten primary

goals or value types exist:

stimulation,

self-direction,

power, achievement, hedonism,

universalism,

benevolence,

tradition, conformity, and security.

Personality

Personality

refers

people to feel, think,

Five

Personality

Model

to

individual

traits

that

and act in certain ways.

(Digman,

1990;

Goldberg,

cause

The Big

1990)

identifies five personality traits including extroversion,

agreeableness,

conscientiousness,

neuroticism,

openness to experience.

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

and

6

Subjective Well-Being

Subjective well-being represents the extent to which

an

individual

feels

good

about

his/her

experiences positive or negative moods.

define subjective well-being:

life

and

Three components

life satisfaction, positive

affect, and negative affect (Diener, 1984).

Atti tudinal Variables

This

dissertation

satisfaction,

commitment,

satisfaction and

commitment

examines

and

involvement

pertains

to

three

work

involvement.

are primarily

one's

attitudes—

While

task-related,

relationship

with

the

organization.

Job Satisfaction

Job

satisfaction

refers

to

the

feelings one experiences on the job

job satisfaction

suggests

that an

degree

(Locke,

of

1976).

individual

about specific work responsibilities

positive

High

feels

good

and his/her ability

to accomplish them.

Organizational Commitment

An

identification

with

and

involvement

particular

organization

characterize

commitment.

Three factors comprise its definition:

in

a

organizational

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

(1) an

7

acceptance

of

organizational

goals

and

values,

(2)

a

willingness

to act in the interest of the organization.,

and

desire

(3)

a

to

remain

part of the

organization

(Mowday, Steers, and Porter, 1979).

Job Involvement

Job involvement refers to one's

the job itself

mean

that

an

(Locke,

1976) .

individual

identification with

High job involvement may

places

importance

on work

and

views his/her job as a meaningful assignment.

Behavioral

Behavioral variables

in this dissertation relate to

important individual and organizational outcomes.

These

outcomes include turnover intentions and job performance.

Furthermore,

job performance refers to both

in-role and

extra-role behavior.

Turnover Intentions

Voluntary

turnover

refers

termination of employment

Meyer,

1993).

capture,

surrogate

Because

to

with a given

actual

turnover

an

individual's

company

(Tett

is difficult

&

to

this dissertation uses turnover intentions as a

measure.

Turnover

intentions

individual's desire to leave an organization.

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

describe

an

8

Job Performance

Job performance typically occurs

role or extra-role behavior

through either in­

(Williams & Anderson,

1991) .

In-role performance refers to behaviors that are part of

the

job

description

functioning

behaviors

while

that

and

necessary

extra-role

are

not

for

effective

performance

includes

prescribed

by

the

job

but

do

contribute to organizational effectiveness.

The Importance of Religious Involvement

Recently,

tremendous

the

topic

attention

in

of

the

religion

popular

has

press.

received

Articles

focusing on religious expression, religious accommodation,

and

spirituality

magazines

Ferguson

have

(Christian

& Lee,

printed

1997;

Workplace."

major

cover

the

Century,

Business Week (Conlin,

have

graced

Flynn,

pages

1997;

1998).

numerous

Pouliot,

1996;

For example,

1999) and HR Magazine

stories

of

entitled

both

(Digh, 1998)

'Religion

in

the

Several polls also show that religion is a

concern

for many

Americans.

A

1999

Gallup

Poll

found that 6 out of 10 Americans consider religion to be

an

important

addition,

part

Business

of

their

Week

life

reported

(Newport,

that

78

1999) .

In

percent

of

Americans felt a need for spiritual growth in 1999, which

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

9

was up

from 20 percent in 1994

(Conlin,

1999) .

Thus,

religion seems to be an increasingly important issue for

Americans in today's society.

While the interest in religion in the workplace may

be

on

the

rise,

effects is not.

involvement

the

empirical

Prior research suggests,

involved

characteristics

religiously involved

can

manifest

individuals

than

(Donahue,

themselves

in

tend

individuals

1985).

the

1974;

1980;

Donahue

Chamberlain

& Benson,

&

1995) .

possess

who

are

not

These differences

form

Zika,

however,

to

of

dispositions,

attitudes, and behaviors (Schwartz & Huismans,

& Fleck,

religion's

in religion affects his/her work environment

religiously

different

on

Questions concerning how an individual's

are still unanswered.

that

research

1992;

1995; Wiebe

Ruh

In addition,

& White,

religious

involvement offers some individuals a sense of direction

and

ultimate

meaning

in

life

(Allport,

1956) .

These

individuals often view work as a calling rather than a job

and

may

general

express

greater

(Davidson & Caddell,

religious

involvement

has

appreciation

toward

1994; Allport,

the

potential

life

1956).

to

in

Thus,

affect

the

workplace through its impact on individual value systems,

and ultimately job attitudes and behaviors.

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

10

Religious

involvement

can

impact

dispositional

characteristics,

particularly values such as forgiveness,

tradition,

and

conformity

Huismans,

1995).

(Rokeach,

Religious

conceptually

linked

involvement with

1994) .

affect

value

Finally,

workplace

religious

behaviors

of hard work

1998).

beliefs

involvement

(Weber,

1958;

In support of this view,

its

literature

and

& Caddell,

can

positively

emphasis

Stone-Romero

Weber's

&

also

commitment,

(Davidson

through

may

Previous

satisfaction,

religious

Schwartz

involvement

positively influence job attitudes.

has

1969;

on

the

& Stone,

(1958)

classic

thesis suggests that religious beliefs shape the everyday

conduct of individuals as well as their approach to work.

Weber's belief is summarized in the following passage:

The magical and religious forces, and the ethical

ideas of duty based upon them have in the past

always been among the most important formative

influences on conduct (Weber, 1958: 27).

Statement of the Problem

Previous

influence

behavior

of

in

research

religion

the

has

on

workplace

recognized

dispositions,

(Schwartz

&

Davidson & Caddell, 1994; Hunt & Vitell,

the actual impact of religious

empirically tested.

the

potential

attitudes,

Huismans,

1986).

and

1995;

However,

involvement has not been

For example,

Stone-Romero and Stone

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

11

(1998)

suggest

behavior

that

through

religion

values.

influences

Other

individual

research,

however,

suggests that religious involvement directly affects both

attitudes and behavior

White,

1974).

(Davidson & Caddell,

1994; Ruh &

Thus, while religious involvement has the

potential to affect workplace behaviors,

how that effect

manifests itself is uncertain.

Thus,

research

is

involvement and values

needed

to

explain how

religious

affect workplace behaviors.

The

present dissertation addresses this problem by examining

the following research questions:

1.

Is religious

attitudes?

involvement

associated

with

job

2.

Is

religious

involvement

associated

with

important individual and organizational outcomes?

3.

Are dispositional characteristics associated with

job attitudes?

4.

Do job attitudes mediate the relationship between

religious involvement and individual behaviors in

the workplace?

5.

Do job attitudes mediate the combined effect of

religious

involvement

and

dispositional

characteristics on individual behaviors in the

workplace?

Researchers have also struggled with the appropriate

method for measuring religious

studies

Religious

have

relied

Orientation

on

the

Scale,

involvement.

Allport

others

and

While some

Ross

have

Reproduced with permission o f the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

(1967)

developed

12

alternative unidimensional and multidimensional approaches

(Cornwall

However,

has

et

no

been

al.,

1986;

Gorsuch

consistent measure

used.

According

to

&

McPherson,

of religious

Kirkpatrick

1989).

involvement

(1989),

the

development or improvement of religious scales would be a

worthwhile venture for future research.

Objectives of the Study

The

purpose

of

the

present

dissertation

is

to

empirically examine the impact of religious involvement on

job attitudes and workplace behaviors.

In addition,

the

relationship between dispositions and attitudes along with

the potential mediating effect of job attitudes will be

investigated.

Figure 1.1 depicts these relationships.

Plan of the Study

Figure 1.2 provides an outline of the entire research

process for this dissertation.

Research Purpose

As

previously

dissertation

is

stated,

to

the

empirically

purpose

of

assess

the

the

present

effect

that

religious involvement has on job attitudes and behaviors.

Furthermore,

the

relationship

between

dispositions

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

and

13

Figure 1.2

Research Process

Research Purpose

To empirically examine the impact of religious

involvement on job attitudes and workplace behaviors.

To investigate the relationship between dispositions

and job attitudes. To determine the potential

mediating effect of job attitudes.

Hypotheses Development

Literature search to support hypotheses development.

Hypotheses relate to five research questions.

Research Methodology

Questionnaire sent to two local companies, comprised

of 375 employees and 40 supervisors. Surveys

attached to payroll check and returned via mail.

Sample Methodology

113 employees and 22 supervisors

Statistical Techniques

Descriptive Statistics

Hierarchical Regression Analysis

Mediated Regression Analysis

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

14

attitudes along with the potential mediating effect of job

attitudes will be examined.

Hypotheses Development

Several hypotheses were developed based on existing

theory

and

literature.

Each

category

of

corresponds to the five research questions.

hypotheses

The specific

hypotheses are listed below.

Religious Involvement

and Job Attitudes

HI:

Individuals who are highly involved in religion will

experience more

job

satisfaction,

organizational

commitment,

and

job

involvement

than

other

individuals.

Religious Involvement

and Workplace Behaviors

H2a: Individuals who are highly involved in religion will

have

lower

turnover

intentions

than

other

individuals.

H2b: Individuals who are highly involved in religion will

perform more positive in-role behaviors than other

individuals.

H2c: Individuals who are highly involved in religion will

perform more positive extra-role behaviors than other

individuals.

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

15

Dispositions and

Job Attitude*

H3a: Individuals who exhibit value types associated with

self-transcendence or conservation will experience

more job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and

job involvement than other individuals.

H3b: Individuals who exhibit value types associated with

change

will

or

openness

to

self-enhancement

organizational

job

satisfaction,

experience

less

than

other

job

invo 1vement

commi tment,

and

individuals.

exhibit

life

satisfaction

will

H3c: Individuals

who

job

satisfaction,

organizational

experience more

job

involvement

than

other

commitment,

and

individuals.

H3d: Individuals

who

exhibit

positive

job

satisfaction,

experience more

job

invo 1vement

commitment,

and

individuals.

affect

will

organizational

than

other

H3e: Individuals

who

exhibit

negative

experience

less

job

satisfaction,

commitment,

and

job

involvement

individuals.

affect

will

organizational

than

other

The Mediating Role

of Job Attitudes

H4a: Job attitudes will mediate the relationship between

religious involvement and workplace outcomes.

H4b: Job attitudes will mediate the interactive effect of

religious involvement and value types on workplace

outcomes.

H4c:

Job attitudes will mediate the interactive effect of

religious involvement an.d subjective well-being on

workplace outcomes.

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

16

Raaaarch Methodology

The following section briefly discusses the research

design used to investigate the hypotheses.

this

discussion

are

the

sample

Included in

methodology,

the

data

collection procedures, and the statistical techniques.

Sample Methodology

The

sample

for

this

dissertation

included

the

employees of two companies from the same geographic area.

The first company consisted of an auto parts distributor

with approximately 75

second company,

locations

a

with

employees and 3 supervisors.

rehabilitation hospital,

approximately

300

The

included

employees

and

two

37

supervisors.

Data Collection

Procedures

Two

questionnaires

supervisory

employees

were

and

administered—one

one

to

supervisors.

employee survey consisted of four sections:

information,

(2)

information,

and

supervisor

Both

survey

groups

questionnaire,

job

contained

received

and

information,

(4) demographic

a

a

only

cover

nonThe

(1) religious

(3)

background

information.

behavioral

letter,

postage-paid

to

a

envelope

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

The

questions.

copy

with

of the

their

17

payroll check.

A total of 113 non-supervisory surveys and

22 supervisor surveys were obtained# with. 100 employee and

21

supervisor

questionnaires

from

the

rehabilitation

hospital and 13 employee questionnaires and 1 supervisor

survey from the auto parts distributor.

Statistical Techniques

Several

statistical

dissertation.

used

to

methods

were

needed

in

this

Both reliability and factor analysis were

determine

unidimensionality

Hierarchical

the

of

internal

consistency

previously

regression

analysis

and

developed

scales.

used

examine

was

to

Hypotheses l-3d.

Hierarchical regression analysis depicts

changes

dependent

in

the

variables

are

added

mediated

regression

Hypotheses 4a-4c.

variable

(Cohen

&

as

Cohen,

analysis

was

new

independent

1975).

Finally,

employed

to

According to Baron and Kenny

test

(1986),

this approach is appropriate for assessing the linkages in

a mediation model.

Contributions of the Study

This

dissertation

contributions

clarifies

workplace

the

to

the

role

by placing

makes

study

of

several

of

religion.

religious

it within

significant

a

First,

involvement

theoretical

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

in

it

the

framework

18

that

is

grounded in previous

research.

The

theory of

planned behavior has been applied to numerous empirical

settings

from

voting

provide useful

religious

and

shoplifting

information

behavior relationship

incorporating

to

regarding the

(Stone-Romero

religion,

and

the

This

& Stone,

framework

dissertation

to

value-attitude1998).

By

suggests

involvement influences behavior

attitudes.

continues

that

through values

provides

the

first

empirical test of this relationship.

Second,

value

this

types.

individual

value

While previous

values,

types

types

dissertation

the present

(Schwartz

represent

examines

the

literature

has

study

& Huismans,

universal

Schwartz

and Huismans

of

focused on

concerned with

1995).

These

characteristics

individuals possess to some degree

1995).

is

impact

value

that

all

(Schwartz & Huismans,

(1995)

suggest

that

this

type of approach allows for the formulation of integrated

hypotheses that relate all of the value types to different

attitudes and behaviors.

Third,

this

dissertation

uses

several

measurement

scales that incorporate multiple dimensions of religious

involvement.

The

improves

likelihood

the

use

of

different

of

religious

capturing

the

religious involvement.

Reproduced with permission o f the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

measures

concept

of

19

Overview of the Study

Chapter 1 provides an outline of this dissertation by

presenting

the

religious

research

involvement,

problem,

the

the

theoretical

importance

framework,

objectives and plan of the present dissertation,

significant

presents

contributions

of

the

study.

a review of the relevant

involvement,

dispositions,

workplace

behaviors.

Chapter

methodology

data

including hypotheses

collection

Chapter

4

procedures,

presents

the

and

data

the

and the

Chapter

2

literature concerning

religious

3

of

job

attitudes,

outlines

the

and

research

development,

sample

statistical

techniques.

analysis,

and

Chapter

and

5

provides the conclusions, limitations, and recommendations

of the study.

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

CHAPTER 2

REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

This

chapter reviews

religious

involvement,

workplace

behaviors.

relevant

literature

dispositions,

The

first

job

concerning

attitudes,

section of

the

and

chapter

outlines the theoretical framework for this dissertation.

The

next

section

identifies

chapter

describes

specific religious

reviews

three

religion

in

general

and

affiliations.

Third,

the

conceptualizations

of

religious

involvement that encompass the characteristics associated

with

religious

individuals.

The

fourth

section of

the

chapter defines the concept of religious involvement,

and

the fifth section suggests possible relationships between

religious

involvement

and

attitudes,

and workplace

individuals'

behaviors.

identifies values, personality,

dispositions, job

The

sixth

section

and subjective well-being

as dispositional antecedents to job attitudes.

Finally,

the last section describes the impact of job attitudes on

workplace

behaviors such

as

absenteeism,

20

R eproduced with permission o f the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

turnover,

job

21

performance, unethical behavior, and religious expression.

The chapter concludes with a brief summary.

Theory of Planned Behavior

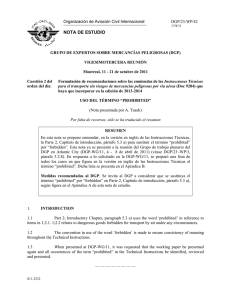

The theory of planned behavior, shown in Figure 2.1,

is

a

social

relationship

psychological

between

model

values,

explicating

attitudes,

and

the

behaviors.

The theory suggests that behavior is the end result of an

individual's

intentions

toward

conscious

are a

the

intentions

function of

behavior,

to

three

subjective

act.

Behavioral

antecedents— attitude

norms,

and

perceived

behavioral control.

Attitude

individual's

toward

perception

the

behavior

of positive

refers

or negative

associated with the act itself.

In general,

determine

a particular

one's

attitude

toward

to

an

aspects

two factors

behavioral beliefs and evaluation of outcomes.

behavior:

Behavioral

beliefs refer to the likelihood that a particular behavior

will

lead

to

certain

positive or negative.

outcomes,

which

are

evaluated

as

Thus, attitude toward the behavior

is a function of both behavioral beliefs and evaluation of

outcomes (Ajzen, 1988) .

Subjective

norms

develop

from

perceived

social

pressure to perform or not perform a particular behavior.

Reproduced with permission o f the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

22

Figure 2.1

The Theory of Planned Behavior

Behavioral

beliefs

Evaluation

of

outcomes

Attitude

toward the

behavior

Behavioral

intentions

Subjective

norms

Motivation

to comply

Perceived

behavioral

control

(Ajzen 1988, 1991)

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

Behavior

23

Two factors determine the level of social pressure that

individuals encounter: normative beliefs and motivation to

comply.

Normative beliefs reflect the social influence of

referent others while motivation to comply pertains to a

sense of obligation that individuals

feel. Both normative

beliefs and motivation to comply have an additive effect

on subjective norms (Ajzen, 1988) .

Finally, perceived control relates to the ability of

an

individual

to

engage

in

may

particular

individuals

behavior,

their perceived behavioral control may be

of

individuals

may

behavior.

emotional

disturbances

Third,

opportunity

First,

limit

particular

motivated

may

costs

ability

tragic

reduce

such

perform

as

to

on others

may

lead

low

to

perform

events

their

not

that

having

doubts

a

cause

capabilities.

equipment may prevent behavior performance.

dependence

a

the knowledge and skills

their

Second,

to

behavior.

Although

due to several factors.

be

a

the

right

And fourth,

about

actually

performing the behavior alone (Ajzen, 1988).

Thus,

the

theory of planned behavior suggests

behavioral intentions develop from several factors:

positive

attitude

consistency

confidence

with

in

toward

social

one's

the

behavior,

referents,

ability

to

that

(1) a

(2)

perceived

and (3)

perceived

perform

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

a

behavior.

24

Additionally,

individual

these

values

factors

that

are

serve

as

related

outcomes of

to

a

particular

behavior and referent others.

Although the

theory

of

planned

behavior

offers an

explanation for how values affect attitudes and behavior,

it does not directly stipulate how these values develop

(Stone-Romero & Stone, 1998) .

Thus, a major part of this

dissertation

development

values

focuses

and other

on

the

dispositional

of

individual

characteristics

that

may

influence the attitude-behavior relationship.

Prior work by Stone-Romero and Stone

work quality

provides

relationship

between

researchers

suggest

dedication

and

the

conceptual

religion

that

loyalty

and

personal

evolve

(1998) regarding

background for the

values.

These

values

from religious

such as

teachings.

In return, these values determine individual attitudes and

behavior.

Thus,

performance

through

religion

the

may

indirectly

formation

of

affect

personal

job

values.

Figure 2.2 depicts this relationship using the theory of

planned behavior as a conceptual framework (Stone-Romero &

Stone, 1998) .

Religion

may

also

affect

other

dispositions,

including personality and subjective well-being.

Although

the theory of planned behavior does not elaborate on these

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

25

Figure 2.2

Individual and Social Determinants of Work Quality

^

/

} Religious

! and Moral

Teachings

Behavioral

beliefs (e.g.,

concerning

high quality

work)

Evaluation of

outcomes

(e.g., from

doing high

quality work)

Normative

beliefs (e.g.,

concerning

high quality

work)

Motivation to

comply (e.g.,

with high

quality work

expectations)

Atti tude

toward the

behavior

(e.g., doing

high quality

work)

Moral beliefs

(e.g.,

concerning

high quality

work)

Subjective

norms (e.g.,

concerning

high quality

work)

J

Behavioral

| intentions

1 (e.g..

J intent to

^ do high

I quality

I work)

Perceived

behavioral

control

(e.g., to do

high quality

work)

(Stone-Romero & Stone, 1998)

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

Behavior

(e.g..

doing

high

quality

work)

26

factors, both personality and subjective well-being appear

to be influenced by religious involvement

1980;

Chamberlain

&

Zika,

1992) .

(Wiebe & Fleck,

Incorporating

both

personality and subjective well-being into the framework

suggests

that

these

and behaviors.

factors

indirectly

affect

attitudes

Thus, an expanded version of the theory of

planned behavior provides

religion, dispositions,

a model

for understanding how

attitudes, and behavior all relate

to one another.

Empirical

research

has

supported

the

planned behavior in a variety of settings

1991; Stone-Romero & Stone,

study

to

date

variables

has

such as

well-being.

involvement,

1998) .

examined

religion,

the

theory

(Ajzen,

of

1988,

However, no empirical

role

personality,

of

extraneous

and subjective

This dissertation focuses on how religious

dispositions,

and

job-related

attitudes

affect behavior in the workplace.

Religion

Although no universally accepted definition or theory

of religion exists in social scientific research (Guthrie,

1980),

two

characteristics.

beliefs

perspectives

identify

its

unique

The substantive view asserts that sacred

and practices

characterize

religion.

Reproduced with permission o f the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

In other

27

words,

religion

experiences

by

is

its

distinguished

association

supernatural forces

with

(Pargament,

from

all

higher

1997) .

other

beings

and

In contrast,

the

functional view suggests that religion's uniqueness comes

from its significance in society and defines religion in

terms of its ability to deal with fundamental problems of

existence.

beliefs,

itself

Thus,

the substantive perspective

feelings,

while

focuses on

and behaviors associated with religion

the

functional

perspective

relates

these religious elements are put into practice

to how

(Pargament,

1997).

Although

insight

each

into

of

the

these

perspectives

nature

of

offers

unique

the

general

religion,

conclusion is that an operational definition of religion

must

be

developed

for- each

Burnett,

1990).

For

religion

represents

research

the purpose

one's

study

of this

involvement

faith through religious beliefs,

(McDaniel

dissertation,

in a

feelings,

&

particular

and practices

(Pargament, 1997).

Western Religions

Various

practices

belief

systems,

characterize

(Stone-Romero

&

Eastern

Stone,

rituals,

and

1998).

doctrines,

Western

As

Reproduced with permission o f the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

and

societies

a

result,

28

generalizations

about

religion

and

comparisons

religion to another are extremely difficult.

the

problem,

this

dissertation

involvement

in

two

Christianity

and

Judaism.

on

personal

religions— specifically,

Both

of

these

religions

emphasize beliefs that relate to work in general

Romero & Stone,

the

following

1998; Davidson & Caddell,

sections

provide

one

To minimize

focuses

Western

of

a

(Stone-

1994).

description

Thus,

of

these

religions along with specific workplace implications.

Christianity

Three major divisions of Christianity exist:

Orthodoxy,

Roman

Catholicism,

Catholicism and Protestantism,

this dissertation

and

Protestantism.

faiths

(Stone-Romero & Stone,

teach mutual

unselfish behavior

Two,

are especially relevant to

1998).

similarities exist between these two faiths.

both

Eastern

respect,

(Stone-Romero

Several

For example,

the Golden Rule,

& Stone,

1998).

and

Thus,

individuals tend to feel responsible for the welfare of

others.

Both faiths view God as a Supreme Being with the

capability

of

Consequently,

responsible

religious

both

punishing

they teach

for

that

practicing

teachings.

and

rewarding

humans.

Christian individuals

behavior

Finally,

both

consistent

the

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

Catholic

are

with

and

29

Protestant

faiths

regard

religious matters.

moral

and

that

as

a guide

on

all

As a result# the Bible functions as a

spiritual

Christian

the Bible

handbook for

individuals

have

questions

or

(Stone-Romero

concerns

&

Stone#

1998).

The Christian religion also emphasizes the importance

of

work

(Stone-Romero

Thessalonians

(3:10)

& Stone,

1998).

For example,

2

states that mFor even when we were

with you, this we command you, that if any would not work,

neither should he eat."

Thus, Christian individuals may

work hard due to their belief in asceticism or the idea

that

hard

Stone,

work

1998).

is

As

a

moral

obligation

a result,

(Stone-Romero

&

followers of the Christian

religion tend to view work as a calling and encounter a

greater sense of responsibility toward its success (Weber,

1958; Davidson & Caddell, 1994).

Although

Catholicism

axe

obvious

and

Protestantism

differences

share

between

the

some

beliefs,

there

two

faiths.

One major difference is that Catholics recognize

an earthly authority (the Pope) on matters of faith while

Protestants reject the idea of sacred agents (Stone-Romero

& Stone,

1998) .

Another difference relates to salvation.

In Catholicism, the church and its associated rituals are

necessary

for attaining grace.

However,

the

Reproduced with permission o f the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

Protestant

30

faith views the church as an insignificant contributor to

this

process

(Stone-Romero

&

Stone,

1998) .

Finally,

Catholics and Protestants may differ regarding their work

ethic.

and

While Protestantism stresses a belief in hard work

self-denial,

work

as

a

contemporary Catholics

tool

for

maintaining

may

simply view

order.

Thus,

some

researchers argue that Protestants harbor a special work

ethic that causes them to take their job more seriously

(Hulin & Blood,

1968; Weber,

1958) .

ethic,

is

encourages

as

it

called,

The Protestant work

people

of

the

Protestant faith to view work as a worldly calling.

Despite

(1998)

these

suggest

arguments,

that

the

Stone-Romero

differences

between

and

Stone

the

work-

related beliefs of Protestants and Catholics are far less

significant

than

maintained

serves

by

as

previous

the

researchers.

Because

Christianity

foundation

for

both

faiths,

Protestants and Catholics tend to regard work as

an important part of everyday life.

Judaism

Judaism

Christianity.

well

as

teaches

belief

in

one

God,

as

does

For Jews, God represents love and mercy as

justice

and punishment.

In

addition,

Judaism

stresses several beliefs concerning human beings such as;

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

31

(1) Jews are God's children (2) Jews have immortal souls

but

mortal

guiding

bodies,

their

(3)

Jews

have

behavior,

and

(4)

moral

Jews

standards

value

justice,

knowledge, and change (Stone-Romero & Stone, 1998) .

with

these

beliefs,

importance of work.

sacred

result,

event

Jews

excellence

values

also

Along

stress

the

In fact, Jews believe that work is a

that

glorifies

strive

in

Consequently,

Judaic

for

hard

order

followers

God

to

in

every way.

achieve

a

to

meet

God's

of

Judaism

tend

high

As

level

a

of

expectations.

to

internalize

religion and view work as the key to their success (StoneRomero & Stone, 1998).

Although

each

major

religion

is

characterized

by

strong religious beliefs, individuals can claim membership

without

only

being overtly

occurs

when

religious beliefs,

being.

the

religious.

individual

Religious

involvement

personally

experiences

feelings, or practices toward a higher

Based on this understanding, religious involvement

serves as the main study variable of this dissertation.

Religious Involvement Conceptualizations

For over three

decades,

the

study of religion has

been a major topic in the fields of both psychology and

sociology.

Recently,

terms such as religiosity

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

(McDaniel

32

&

Burnett,

1990;

religiousness

orientation

Barnett,

(Clark

&

Bass,

Dawson,

&

Brovin,

1996),

(Davidson & Caddell,

1994)

and

1996) ,

religious

have appeared in

the business

literature in a few empirical studies that

attempt

explicate

to

involvement

in

the

the

consequences

workplace.

of

Although

religious

each

of

these

terms identifies an aspect of religious involvement, their

meanings are not identical (see Table 2.1) .

Religiosity

Alternative

Simmel

explanations

(1906)

defines

of

religiosity

religiosity

as

an

attitude toward or capacity for religion.

exist.

individual

In other words,

religiosity is a spiritual quality or characteristic that

varies

in

degree.

religiosity

Individuals

should

possess

religion (Trevino, 1998).

religiosity

is

a

a

with

a

positive

high

level

attitude

of

toward

Thus, an individual's degree of

strong

indicator

of

his/her

religious

involvement.

According to Cornwall et al.

basic

affect

components

(feeling),

component

of

orthodoxy

of

of

religiosity:

and behavior

religiosity

a

(1986), there are three

person

and

cognition

(doing).

refers

to

involves

(knowing),

The

the

the

cognitive

beliefs

acceptance

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

or

or

33

Table 2.1

Similarities and Differences of

Religious Involvement Conceptualizations

Raligiou

• Teem

Definitions

Religiosity

(Cognition,

Affect, and

Behavior)

Attitude

Personality

Need

Commitment

Affiliation

Religiousness

(Substantive

and

Functional)

Religious

Orientation

(Intrinsic

and

Extrinsic)

Belief

Practice !

Response

Motivation

Personality

Cognitive

style

Differences

Substantive

Religiousness

and Intrinsic

Religious

Orientation

Functional

Religiousness

and Extrinsic

Religious

Orientation

(Substantive)

Religiosity

and Intrinsic

Religious

Orientation

(Substantive)

Extrinsic

Religious

Orientation

(Functional)

Extrinsic

Religious

Orientation

(Functional)

Religiosity

and Intrinsic

Religious

Orientation

(Intrinsic)

Religiosity

and

Substantive

Religiousness

(Intrinsic)

Functional

Religiousness

(Extrinsic)

Functional

Religiousness

(Extrinsic)

Religiosity

and

Substantive

Religiousness

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

34

rejection

of

a

organization.

particular

doctrine

affective

component

The

or

religious

of

religiosity

involves an individual's feeling and commitment toward a

religion.

emotional

In

sense,

attachment

institution.

an

this

to

Finally#

religiosity

a

higher

such

as

attending

financial contributions,

being

or

in

a particular

worship

an

religious

the behavioral component

individual's participation

Practices

represents

includes

religion.

services,

making

or praying are examples

of

the

behavioral component of religiosity.

As shown in Table 2.2, each of these components can

be divided into two modes of religiosity (Cornwall et al.,

1986).

The personal mode consists of beliefs,

feelings,

and behaviors related to an individual's private practice

of religion.

faith