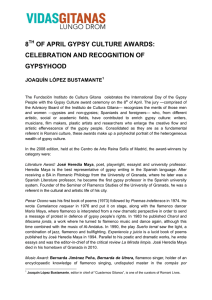

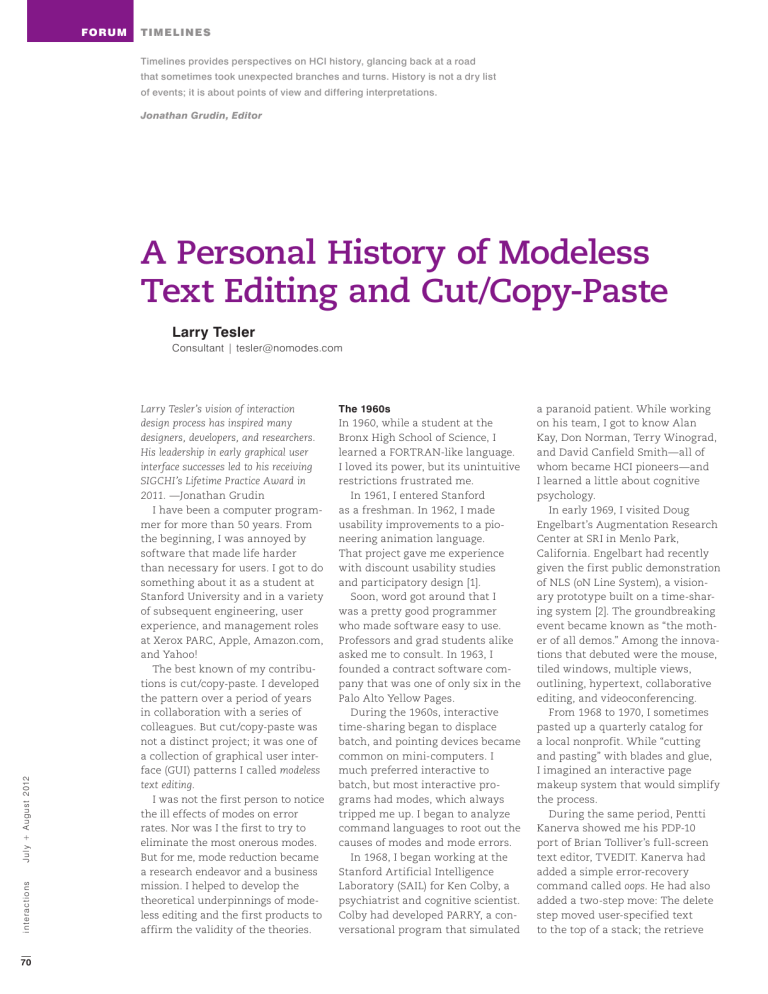

FORUM timelines Timelines provides perspectives on HCI history, glancing back at a road that sometimes took unexpected branches and turns. History is not a dry list of events; it is about points of view and differing interpretations. Jonathan Grudin, Editor A Personal History of Modeless Text Editing and Cut/Copy-Paste Larry Tesler i n t e r a c t i o n s J u l y + A u g u s t 2 0 12 Consultant | tesler@nomodes.com 70 Larry Tesler’s vision of interaction design process has inspired many designers, developers, and researchers. His leadership in early graphical user interface successes led to his receiving SIGCHI’s Lifetime Practice Award in 2011. —Jonathan Grudin I have been a computer programmer for more than 50 years. From the beginning, I was annoyed by software that made life harder than necessary for users. I got to do something about it as a student at Stanford University and in a variety of subsequent engineering, user experience, and management roles at Xerox PARC, Apple, Amazon.com, and Yahoo! The best known of my contributions is cut/copy-paste. I developed the pattern over a period of years in collaboration with a series of colleagues. But cut/copy-paste was not a distinct project; it was one of a collection of graphical user interface (GUI) patterns I called modeless text editing. I was not the first person to notice the ill effects of modes on error rates. Nor was I the first to try to eliminate the most onerous modes. But for me, mode reduction became a research endeavor and a business mission. I helped to develop the theoretical underpinnings of modeless editing and the first products to affirm the validity of the theories. The 1960s In 1960, while a student at the Bronx High School of Science, I learned a FORTRAN-like language. I loved its power, but its unintuitive restrictions frustrated me. In 1961, I entered Stanford as a freshman. In 1962, I made usability improvements to a pioneering animation language. That project gave me experience with discount usability studies and participatory design [1]. Soon, word got around that I was a pretty good programmer who made software easy to use. Professors and grad students alike asked me to consult. In 1963, I founded a contract software company that was one of only six in the Palo Alto Yellow Pages. During the 1960s, interactive time-sharing began to displace batch, and pointing devices became common on mini-computers. I much preferred interactive to batch, but most interactive programs had modes, which always tripped me up. I began to analyze command languages to root out the causes of modes and mode errors. In 1968, I began working at the Stanford Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (SAIL) for Ken Colby, a psychiatrist and cognitive scientist. Colby had developed PARRY, a conversational program that simulated a paranoid patient. While working on his team, I got to know Alan Kay, Don Norman, Terry Winograd, and David Canfield Smith—all of whom became HCI pioneers—and I learned a little about cognitive psychology. In early 1969, I visited Doug Engelbart’s Augmentation Research Center at SRI in Menlo Park, California. Engelbart had recently given the first public demonstration of NLS (oN Line System), a visionary prototype built on a time-sharing system [2]. The groundbreaking event became known as “the mother of all demos.” Among the innovations that debuted were the mouse, tiled windows, multiple views, outlining, hypertext, collaborative editing, and videoconferencing. From 1968 to 1970, I sometimes pasted up a quarterly catalog for a local nonprofit. While “cutting and pasting” with blades and glue, I imagined an interactive page makeup system that would simplify the process. During the same period, Pentti Kanerva showed me his PDP-10 port of Brian Tolliver’s full-screen text editor, TVEDIT. Kanerva had added a simple error-recovery command called oops. He had also added a two-step move: The delete step moved user-specified text to the top of a stack; the retrieve Timelines FORUM How Modes Degrade Usability The 1970s In 1971, Les Earnest, director of the A.I. Lab, asked me to design and implement a page-makeup language that could number sections and generate an index, table of contents, footnotes, crossreferences, and so on. I proposed to make it interactive, but he wanted a batch system, which I admitted would be easier. In a few months of intense work, I created PUB: The Document Compiler [3]. PUB was a markup language with embedded tags and scripting. It became popular among graduate students at ARPANETconnected universities. In 1973, I joined Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) as a member of the PARC Online Office System (POLOS) team but spent some of my time working on Smalltalk with Alan Kay’s Learning Research Group. One reason I was interested in working with Kay was that his invention of overlapping windows was motivated by a desire to find alternatives to modes. Most members of the POLOS team had come to Xerox from Engelbart’s group at SRI. My manager, Bill English, had been involved in the design of the mouse, co-authored Engelbart’s 1968 paper, and managed the famous NLS demo. From its inception, NLS was used mainly to construct and revise technical specifications, source code, and other indented outlines. Its regular users found it a good fit for that. But I felt that it would not gain public acceptance as a tool for editing common documents such as letters, memos, and forms. Its command language had numerous modes. Outside text-entry mode, virtually every keystroke and click changed the mode. The syntax of the NLS command language evolved over time, but it was always prefix, in which the verb is specified before its object (see Figure 1 and sidebar: “How Modes Degrade Usability”). To delete a paragraph, you told NLS to delete before you told it what paragraph it should delete. Clicking the mouse button when the pointer was over something was called marking. Three frequently used NLS commands that required marking were: In a 1981 article about Smalltalk [9], I defined a mode as “a state of the user interface that lasts for a period of time, is not associated with any particular object, and has no role other than to place an interpretation on operator input.” Three properties of a command language that cause mode-related problems are: • Verbs precede their objects. The most frequently used commands in many interactive systems involve a verb and one object. If the language has any consistency at all, there is prevalent command syntax, which is usually either prefix or suffix. The distinction is whether the user specifies the verb before or after its object. Suffix syntax has a usability advantage: When the user specifies the verb last, its object has already been specified, and the command can be executed immediately. Systems that use prefix syntax must enter a mode to wait for the user to specify the object. Keeping track of mode changes can distract a user from the task at hand. • Key meanings are mode-dependent. Languages that use unmodified letter keys to do anything but enter those letters as text need at least two modes: text and command. If unmodified letter keys are typed in command mode but the user thinks the system is in text mode, D(elete) W(ord) <mark affected word> <ok> unintended and sometimes disastrous results ensue. M(ove) T(ext) <mark source text start> <mark source text end> <mark destination> <ok> in a mode. An oft-heard question is, “How do I get out of I(nsert) S(tatement) <mark destination> <type text to insert> <ok> The command-accept action, symbolized here by <ok>, could be invoked from either the keyboard or the mouse. Text was an arbitrary span of text. A statement was usually a paragraph. As the user typed and clicked, pieces of a command line accumulated in a visible window. The user could remove the newest piece of the command line from the window or erase the whole line and start over. When the user invoked <ok>, NLS erased the whole line, preventing further modification. • Mode escapes are inconsistent. Users often get “stuck” this mode?” Then it performed the command. Because move was a single command, both the destination and the source had to be visible onscreen before typing “M.” The same restriction applied to copy and replace. Features such as collapsible outlines provided ways to circumvent the restriction, but the user had to learn more syntax and plan ahead. I believed that competitors would surpass Xerox in speed of learning and ease of use if we stayed with NLS syntax. Most of my colleagues were unconcerned. They considered NLS intuitive because of its English-like verb-object grammar. The syntax allowed a i n t e r a c t i o n s J u l y + A u g u s t 2 0 12 step moved the top element of the stack to a user-designated location. Between steps, the user could do anything that left the stack intact, including filing, searching, typing, and moving other text. Although TVEDIT had modes, it seemed to me that a two-step move and an oops-like error-recovery command could help to make a suitably designed editor modeless. 71 FORUM •F igure 1. NLS prefix syntax, simplified. Timelines verb Delete Move Insert Replace noun mark Character Word Statement Text (2 marks) mark type •F igure 2. Modeless suffix syntax. Click Click & Drag •F igure 3. Error recovery with NLS prefix syntax. verb verb object noun mark verb select i n t e r a c t i o n s J u l y + A u g u s t 2 0 12 type 72 Cut Paste typing Backspace backs up one step. Command Delete starts over. •F igure 4. Error recovery with modeless suffix syntax. OK lot of room for growth. And the command line made it possible to use NLS from older terminals. During my first week on the job, Bill English asked me to work with another new hire, Jeff Rulifson, to develop a vision of the future of editing. Rulifson and I met several times to brainstorm. When OK mark type Selection error? Reselect. Command error? Undo. I confided my concerns about the NLS command language, he revealed that he had designed it. He had meant it to serve as a temporary tool for software testing. Engelbart’s team had run usability studies and made incremental improvements, but they had not seriously considered suffix syntax, in which the verb is specified after its object (see Figure 2 and sidebar: “How Modes Degrade Usability”). I told Rulifson about the errorrecovery advantages of suffix syntax (see Figures 3 and 4), namely: • If the user made a selection mistake while specifying the object, she could simply select again. There was no need to back up in the command line. There was no need to display a command line. • If the user chose the wrong verb, the consequences became immediately visible. To correct the mistake, she could invoke an operation that undid the command. I had not previously seen an error-recovery command more general than TVEDIT’s oops. Rulifson told me about one that our PARC colleague, Warren Teitelman, had introduced in his user-friendly LISP shell. It was aptly named undo. And it became our model. Rulifson and I also discussed the use of graphics in interfaces. He had recently read a book about semiotics that defined an icon as a labeled pictogram and mentioned its potential relevance to interactive computing. We circulated a few versions of a white paper around PARC. It was entitled “OGDEN: An Overly General Display Editor for Non-programmers.” We proposed iconic user interfaces with desks and file cabinets. We also proposed modeless postfix syntax with cut and paste. Rulifson’s willingness to turn the user interface he had designed for NLS on its head made it much easier to get the rest of the POLOS team to consider my proposals. With the help of Barbara Grosz, I ran user studies, including blankscreen studies, which laid bare the problems that modes caused [4]. Then, using a very early version of Timelines FORUM Objections to Modeless Editing and Cut/Copy-Paste the Smalltalk language, I developed a simple, typewriter-like editor with very few modes. People who had never touched a computer were able to learn the simple editor in five minutes. Objection 1. User mistakes. After performing a cut, the user might forget that important text was in what we now call the clipboard. She could lose it by cutting or copying something else without an intervening paste or undo. Response: The ability to do other things between cut and paste entails more benefits than risks. Response: A suitable undoing or versioning facility will allow recovery of accidentally deleted data. Objection 2. Implementation cost. When the user invokes cut or copy, then closes the source document before specifying the destination, the software has to retain a copy of the cut or copied material in the clipboard along with fonts, graphics, and so on, just in case a subsequent paste required it. Response: This was a major concern from 1975 to 1982 because early personal computers had so little DRAM and disk space. But we knew that Moore’s Law would soon provide us with enough memory and processing speed to hold on to most clipboards. Response: It is better to burden the developer than the user. A decade later, I turned this argument into the Law of Conservation of Complexity: Every system has an irreducible amount of complexity; the only question is, who is going to have to deal with it? The user? The application programmer? Or the platform developer? Objection 3. Speed. If you were to watch an NLS expert edit a document, you’d see his fingers blazing and hear a drumroll of strokes (mouse clicks and key presses). Observe an expert user of a modeless editor and you’ll hear fewer strokes per unit time. Staccato versus legato. Citing Fitts’s Law, some NLS advocates claimed a speed advantage and attributed it to less hand motion. Response: Stu Card and Tom Moran showed that the command syntax of NLS required more strokes than that of Gypsy, sometimes twice as many, and in some cases, more mental preparation time. A 1981 study by Terry Roberts and Moran compared experienced users of Gypsy to experienced users of NLS and six other well-known editors [13]. The authors found that experienced Gypsy users, on average, performed a benchmark set of tasks in less time than users of the other editors and twothirds the time of NLS. Fewer key and button presses were required. Objection 4: Lack of extensibility. Modes can be removed from text editors, but it is hard to remove the modes from other types of software, such as graphics. Response: In the study cited above, the one measure by which Gypsy trailed other text editors was functionality. But that finding didn’t prove that the modeless model could not be extended, only that it had not been extended. Another decade elapsed before Apple’s Macintosh entered the market and attracted enough applications to prove the model extensible. As for graphics editors, I agree with the common wisdom that modes can be good when they support a metaphor like picking up a brush, and when feedback identifying the current mode is displayed where the user is almost certain to be looking. filing system that supported versions and drafts. The software took a few months to complete. Gypsy introduced several modeless user interface features that are now standard [7]. The user could: • click between characters, see a blinking insertion point appear, and start typing; • down-drag-up to select text; • double-click a word to select it; • move text in two steps called cut and paste; • copy text in two steps called copy and paste; and • to search, type or paste the search text into an editable field. When we began implementa- i n t e r a c t i o n s J u l y + A u g u s t 2 0 12 Gypsy English commended my work but asked me to turn my attention to the POLOS system. I had barely started to do that when serendipity struck. Ginn and Company, a textbook publisher owned by Xerox, asked PARC to build two applications, one for galley editing and one for page layout. English knew I’d be interested and asked me to run the project. He assigned Dan Swinehart to advise me. Swinehart, whom I had worked with at SAIL, was a passionate opponent of modes and a fount of wisdom. My suggestion to use cut and paste in both the page-makeup system and the galley editor delighted Ginn management. I now had a receptive audience for my experiments. In another welcome turn of events, Ginn hired a software engineer named Tim Mott to conduct an ethnographic study at their facility near Boston. In 1974, after completing the study, Mott came to PARC to help me implement the galley editor, which he dubbed Gypsy. By the time he arrived, several Xerox Alto personal computers were in operation. Charles Simonyi and Tom Malloy had gotten an early version of the Bravo text editor running on Alto. Bravo was a pioneering WYSIWYG application, the brainchild of Butler Lampson and Simonyi [5,6,7]. To implement Gypsy, we took Bravo’s source code and replaced the modal user interface with a modeless one. At Ginn’s request, we added bold, italic, and underline type and a 73 FORUM Timelines Gypsy Smalltalk BravoX* i n t e r a c t i o n s J u l y + A u g u s t 2 0 12 •F igure 5. The path to ubiquity. 74 Woodstock Star* LisaWrite MS Word Mac Windows Bus. Week iOS * Modeless insert but no cut/copy-paste tion, I didn’t have all the details of the interface worked out. I figured we would iterate as we developed. What I didn’t count on was Mott’s creativity and how attuned he was to the target users he had observed at Ginn. For example, when none of my proposals for word selection panned out, it was he who came up with the idea of double click. Lesson learned: You don’t have all the answers. Team up. During the development of Gypsy, PARC hired Tom Moran, Stu Card, and Beverly McHugh. They observed me running a usability study and offered to run future studies for us. The studies Beverly ran were invaluable in refining the user interface of Gypsy. Lesson learned: Some people can do what you do better than you can. Team up. When Gypsy was finished in early 1975, Mott brought it to Ginn. The users loved its strengths. But they disliked its weaknesses, especially the almost complete absence of code maintenance, an engineering requirement we researchers had neglected. Lesson learned: If you are going to give your research prototype to users who may grow to depend on it, be sure that someone has planned for maintenance. Influences In June of 1975, Businessweek published a feature article called “The Office of the Future” that mentioned Gypsy. It also mentioned cut and paste, but only in the context of Woodstock, an office-system prototype that Swinehart had developed as he advised us on Gypsy. Other PARC colleagues built on our work. Mott and I had used dedicated keys for cut, copy, paste, and undo. Inspired partly by William Newman’s use of pop-up icon grids in his Markup painting program [8], Dan Ingalls implemented a delightfully simple pop-up menu in Smalltalk that contained a column listing the four command names [9]. That menu evolved into the right-click contextual menus that are commonplace today. Lesson learned: When you think it’s as simple as it can be, there is probably a way to make it even simpler. Gypsy also influenced BravoX and the Xerox Star. BravoX was a successor to Bravo that Simonyi developed at PARC. Star was the first commercial office system with a mouse, bitmapped display, windows, and file servers. Star had a thoroughly consistent and nearly modeless user interface [10]. Both BravoX and Star supported modeless “click and type” insertion, but neither used a two-step cut/copy-paste. The user could perform a move or copy with fewer strokes than Gypsy—two in one version of BravoX and three in Star, versus four in Gypsy. But the trade-off to achieve fewer strokes was a mode that limited what the user could do between source and destination selection. In the early 1980s, Xerox’s modeless editors influenced Apple’s Lisa and Macintosh as well as Microsoft Word, Office, and Windows. The popularity of Microsoft and Apple products made cut/copy-paste and modeless text editing ubiquitous, even reaching smartphones with multitouch screens (see Figure 5). There are still some modes in modern word processors, such as the format paintbrush in Microsoft Word. And designers still experiment with alternative ways to move text, such as drag-and-drop in Word. But these are shortcuts that uninterested users can usually ignore. Post-Gypsy After Mott returned to PARC from Ginn, he joined a different project. Next up for me was the page-makeup system that Ginn had requested. I used Smalltalk to build a prototype called Cypress. After the user made a selection, an edit menu would pop up automatically nearby, as on today’s iPhone. Timelines The 1980s By 1980, Xerox’s copier patents had expired, and the company was fighting for survival. It became clear that we were not going to bring much PARC work to market except the laser printer and the STAR, both aimed at business users. I went to Apple to work on the Lisa user interface and applications. To develop the Lisa User Interface Standards [11], I teamed up with the multitalented Bill Atkinson, who shared my insistence on simplicity. For a few weeks that summer, he would build a prototype almost every night, and I’d run a usability study the next morning. Jef Raskin, who was beginning work on a concept he called Macintosh, was skeptical about the mouse but generously offered suggestions and support. The Lisa software engineers internalized modeless editing principles and found clever ways to make their applications modeless. My job was to manage them and make evidence-based decisions about the design of the interface [12]. One of many contributions the Lisa made to the GUI was the dialog box, a vehicle for providing parameters to a modeless command. Rod Perkins designed Lisa dialog boxes. The typical dialog prevented the user from continuing work while it was open. That made it modal. But the widgets within the dialog could be operated in any order, making it locally modeless. And the mode escape was performed in a consistent way, by clicking dismissal buttons that were consistently located and labeled. At Apple, as at PARC, the new user interface had its skeptics, some of whom preferred the NLS style of interface. But Apple wanted products. “Religious wars” did break out, but they couldn’t last more than a few days. Lesson learned: If you need to fight an uphill battle, choose a short hill. Acknowledgements I am grateful to William Newman, Bill Duvall, Stuart Card, Charles Simonyi, Jeff Rulifson, Terry Roberts, Charles Irby, and Tom Malloy for reviewing drafts and providing factual corrections and insightful perspectives. Any remaining errors are mine. Today In the 1970s, move and copy were edits that users wanted to perform and cut/copy-paste was a new way for users to perform them. Now these terms have reversed roles. Users don’t say they want to “move” things; they say they want to “cut and paste” them. Even scholarly writings about Star, NLS, and other systems with modal moves often refer to their move/copy operations as cut/copy-paste. Before the computer age, the term cut and paste was publishingindustry jargon. The term copy and paste appears to have originated in Gypsy. Both terms are widely understood today. I don’t know who coined copy-paste job or copy-paste error. But when I make a copy-paste error, unlike most people, I have nobody else to blame. 9. Tesler, L. The Smalltalk environment. Byte 6, 8 (Aug. 1981), 90-147. EndNotes: 1. For more information on this project see my 2011 CHI Lifetime Practice Award talk (particularly minutes 6-12); http://dmcc.acm.org/pres/?query=/dmcc/// confdata/chi2011/220-221-222/2011-05-11_09h02 2. Engelbart, D.C. and English, W.K. A research center for augmenting human intellect. Proc. AFIPS Conference (Dec. 1968), 395-410. 3. The manual is on my website: www.nomodes. com/pub_manual.html. 4. For study notes, please see http://nomodes. com/Larry_Tesler_Consulting/1973_User_Study_ Notes.html 5. Lampson, B. Bravo Manual. Alto User’s Handbook. Xerox Palo Alto Research Center, 1976, 26-60. 6. Newman, W. Design case study: The Bravo text editor. interactions 19, 1 (Jan. + Feb. 2012), 75-80. 7. Lampson, B. Personal distributed computing: The Alto and Ethernet Software. Proc. of the ACM Conference on the History of Personal Workstations (Jan. 1986). 8. Newman, W.M. Markup Manual. Alto User’s Handbook. Xerox Palo Alto Research Center 1979, 85-96. 10. Smith, D.C., Irby, C., Kimball, R., Verplank, W., and Harslem, E. Designing the Star user interface. Byte 7, 4 (Apr. 1982), 242-282. 11. Atkinson, B. Lisa User Interface Standards. Apple Computer, Inc., 1980. 12. Perkins, R., Keller, D.S. and Ludolph, F. Inventing the Lisa user interface. interactions 4, 1 (Jan. 1997), 40-53. 13. Roberts, T.L. and Moran, T.P. The evaluation of text editors: Methodology and empirical results. Communications of the ACM 26, 4 (Apr. 1983), 265-283. About the Author Larry Tesler is a freelance consultant in Silicon Valley. He was formerly a member of the research staff at PARC, the chief scientist of Apple, and a user experience vice president at Amazon and Yahoo! This article is based on the Lifetime Practice Award talk he delivered at CHI 2011. DOI: 10.1145/2212877.2212896 © 2012 ACM 1072-5220/12/07 $15.00 i n t e r a c t i o n s J u l y + A u g u s t 2 0 12 Implemented in Smalltalk-76, the Cypress prototype ran so slowly that to demonstrate it, we shot video at three frames per second and played it back at 30fps. By then, Xerox’s priorities had changed, as had my personal interests. Ginn agreed to wait a few years until they could do page layout on a well-maintained commercial system. I developed the Smalltalk Browser, an ancestor of today’s IDE’s (integrated development environments). Outside work hours, I dabbled in hobby computers and developed educational applications for the Commodore PET. Then, in December of 1979, Steve Jobs paid a world-changing visit to PARC and I began rethinking my career. FORUM 75