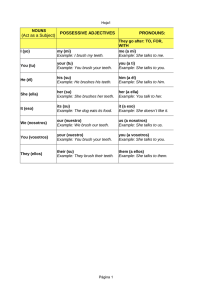

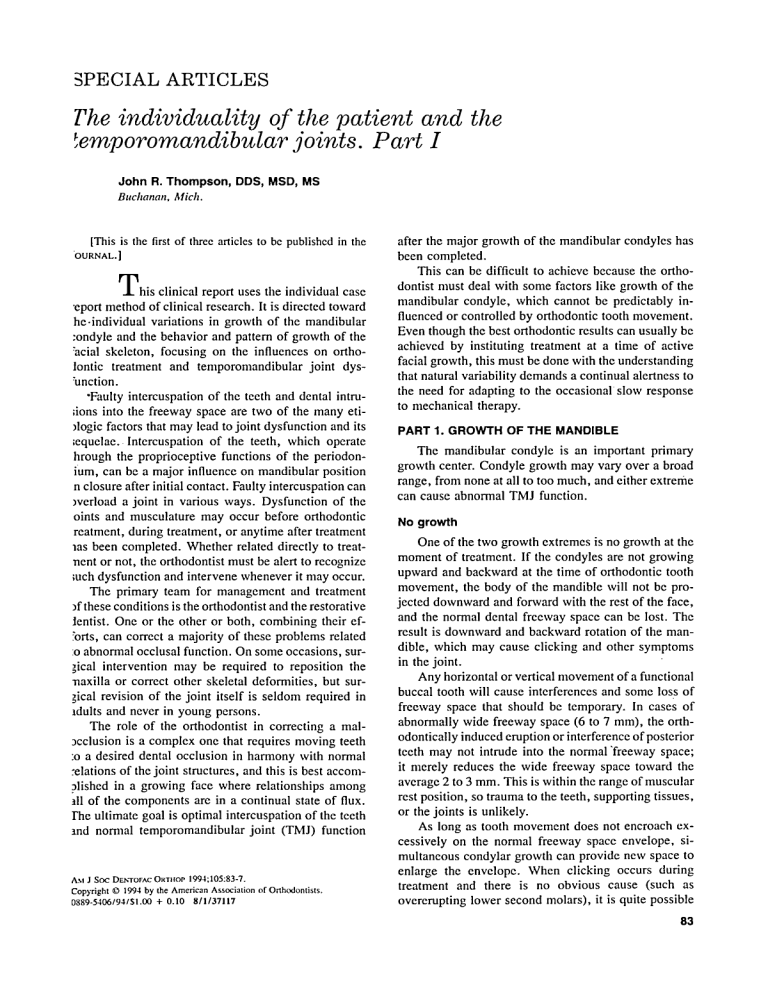

PECIAL ARTICLES The individuality of the patient and the emporomandibular joints. Part I John R. Thompson, DDS, MSD, MS Buchanan, Mich. [This is the first of three articles to be published in the 'OURNAL. ] T h i s clinical report uses the individual case 9eport method of clinical research. It is directed toward he-individual variations in growth of the mandibular :ondyle and the behavior and pattern of growth of the 'acial skeleton, focusing on the influences on ortholontic treatment and temporomandibular joint dys'unction. 9Faulty intercuspation of the teeth and dental intru;ions into the freeway space are two of the many eti)logic factors that may lead to joint dysfunction and its ;equelae. lntercuspation of the teeth, which operate hrough the proprioceptive functions of the periodonium, can be a major influence on mandibular position n closure after initial contact. Faulty intercuspation can )verload a joint in various ways. Dysfunction of the oints and musculature may occur before orthodontic reatment, during treatment, or anytime after treatment aas been completed. Whether related directly to treatnent or not, the orthodontist must be alert to recognize ;uch dysfunction and intervene whenever it may occur. The primary team for management and treatment ffthese conditions is the orthodontist and the restorative tentist. One or the other or both, combining their ef:'orts, can correct a majority of these problems related :o abnormal occlusal function. On some occasions, sur;ical intervention may be required to reposition the naxilla or correct other skeletal deformities, but surgical revision of the joint itself is seldom required in ldults and never in young persons. The role of the orthodontist in correcting a mal9cclusion is a complex one that requires moving teeth :o a desired dental occlusion in harmony with normal :elations of the joint structures, and this is best accomalished in a growing face where relationships among ill of the components are in a continual state of flux. rhe ultimate goal is optimal intercuspation of the teeth tnd normal temporomandibular joint (TMJ) function AM J St-x: Dr~,-ror^c OwnloP 1994;105:83-7. Copyright 9 1994 by the American Association of Orthodontists. 0889-5406194151.00 + 0.10 811137117 after the major growth of the mandibular condyles has been completed. This can be difficult to achieve because the orthodontist must deal with some factors like growth of the mandibular condyle, which cannot be predictably influenced or controlled by orthodontic tooth movement. Even though the best orthodontic results can usually be achieved by instituting treatment at a time of active facial growth, this must be done with the understanding that natural variability demands a continual alertness to the need for adapting to the occasional slow response to mechanical therapy. PART 1. GROWTH OF THE MANDIBLE The mandibular condyle is an important primary growth center. Condyle growth may vary over a broad range, from none at all to too much, and either extreme can cause abnormal TMJ function. No growth One of the two growth extremes is no growth at the moment of treatment. If the condyles are not growing upward and backward at the time of orthodontic tooth movement, the body of the mandible will not be projected downward and forward with the rest of the face, and the normal dental freeway space can be lost. The result is downward and backward rotation of the mandible, which may cause clicking and other symptoms in the joint. Any horizontal or vertical movement of a functional buccal tooth will cause interferences and some loss of freeway space that should be temporary. In cases of abnormally wide freeway space (6 to 7 mm), the orthodontically induced eruption or interference of posterior teeth may not intrude into the normal "freeway space; it merely reduces the wide freeway space toward the average 2 to 3 mm. This is within the range of muscular rest position, so trauma to the teeth, supporting tissues, or the joints is unlikely. As long as tooth movement does not encroach excessively on the nomlal freeway space envelope, simultaneous condylar growth can provide new space to enlarge the envelope. When clicking occurs during treatment and there is no obvious cause (such as overerupting lower second molars), it is quite possible 83 Zhottlpson that either facial growth is inadequate or the orthodontic changes have been too rapid for compensation. A new lateral cephalometrie radiograph will probably show the current mandibular position and any rotation or posterior displacement that may have occurred since an earlier film. The no growth problem is demonstrated in the case reports in part 3 of this series (to be published at a later date). Protracted condyle growth Too much growth can be just as serious as too little. Additional condyle growth after other facial growth has stopped is a special concern because it can alter the occlusion and joint function. There may be no joint clicking or other symptoms at 12 or 14 years of age, yet pronounced symptoms 5 years later. Every patient should be checked regularly, especially through the years immediately after other growth has essentially ceased. The orthodontist should continue to be responsible for this supervision of orthodontic patients. Continuing observation at least once or twice a year is an additional professional service not entirely related to treatment that should be explained before treatment is started. The orthodontist should be the first to detect any clicking or dysfunction, understand the problem, and know how to control it. The temporomandibular joints are the only joints in the body under such precise discipline as that imposed by two rigidly attached, separate but interdependent articulations, and these must also coordinate with the dental occlusion. Every movement of one joint imposes movements and loads on its contralaterai antimere. As the jaw closes and teeth come into contact, the third articulation of this triumvirate becomes dominant. Proprioceptive feedback from the intercuspation of the teeth can then become the primary influence on the position of the condyles in their fossae from initial contact to full closure. Control over jaw movement, however, does not extend to control over condyle growth. Continuing condyle growth will alter occlusal relationships, which in turn will alter joint relationships, but most occlusal relationships cannot be expected to influence condyle growth. Weinmann and Sicher state: "While the dependence of bone growth upon the development of teeth is slight, the reverse relation, that is, the dependence of tooth development and especially, tooth eruption upon growth of bone and bones is considerable.'" That statement remains true. This unique three-way articulation makes the temporomandibular joints the only joints in the body that can grow into an internal displacement (Fig. 1). Com- American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics January 1994 parable growth in an elbow or a knee would simply result in a longer arm or leg, because those joints do not have to content with restricture feedback from another articulation such as the teeth. The cartilage growth centers of the long bones can abut against each other with no problem, but there are compressible, nonarticulatory soft tissues behind and above the cartilage growth centers of the mandibular condyles. These tissues provide a limited measure of adaptability, but they are also subject to injury from excessive functional loads. To fully appreciate the growth pattern of the face, one can refer to the classical studies of Broadbent, 2. 3 Brodie, 4 and Weinmann and Sicher, I which remain the foundation pillars of scientific orthodontics. Broadbent,s 2. 3 study and compilation of the cephalometric radiographs of a large group of children in the Bolton Study showed th e unfolding of a stable growth pattern. From his composite tracings he created an average face for the various ages (Fig. 2). Brodie4 followed with his serial cephalometdc radiographic studies, and he too demonstrated the basic stability of the normal enlarging facial pattern (Fig. 3). At the same time, anatomist and histologist SicheP explained the biologic mechanisms of facial growth. This was an epochal blending of research to explain how the face grows, and his explanation of cartilage growth in the mandibular condyle is particularly appropriate to this report (Fig. 4). Figure 1, A shows the direction of normal condyle growth at ages 8, 10, and 12 years. Fig. 1, B shows normal repositioning of the body of the mandible in response to the growth at the condyle. Fig. 1, C illustrates this normal condyle growth at ages 17 and 18 years and the resulting mandibular repositioning, and Fig. 1, D shows how such condyle growth can produce posterior displacement with resultant clicking when the dental occlusion restricts the normal downward and forward repositioning of the body of the mandible (Thompsonr-S). In considering condyle growth, great care is required in the interpretation of temporomandibular joint radiographs taken before and after a protrusive type of orthodontic treatment of Class II malocclusions, as with a functional appliance. Before treatment radiographs taken with the appliances in place will typically show the condyles to be downward and forward of their normal relation to the articular eminences. After treatment radiographs may show the condyles to be again in their normal positions in the fossae. It is my opinion that this is essentially growth that would also have occurred without treatment of the dental malocclusion; radiographs made with a new protrusive appliance fitted at rnerican Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics ~lume I05, No. l Thompson 85 12Y lOY 8Y ! 8, IOY B A 12u clir / 17y 18jY " ~ - ~ - - - \ ! -\'1 tl 17Y 18Y Fig. 1. Growth of mandible. A, The direction of normal condyle growth at ages 8, 10, and 12 years. B, Repositioning of the body of the mandible in response to the condyle growth. C, Normal condyle growth at ages 17 and 1B years, with normal repositioning of the mandible. D, Condyle growth producing posterior condyle displacement (clicking) should the dental occlusion prevent the normal downward and forward repositioning of the mandible. This repositioning occurs as normal at rest position, but now there would be an abnormal upward and backward path of closure from rest position to the occlusal position. his stage would present a picture similar to the original ~retreatment film. Cephalometric radiographs show imilar progressive downward and forward positioning if the mandibular body in a normal growth pattern. The ontroversy exists over the magnitude of potential :rowth enhancement during therapy. It is my opinion that correction of occlusion with hese appliances is accomplished through disengagenent of the occlusion, which allows the growth changes o alter interocclusal relationships that would otherwise ~e carried along unchanged with growth. This same :ffect is seen with a broad spectrum of treatment ap- proaches; the significant factor is occlusal disengagement, not the particular means by which it may have been achieved. Growth is the essential component. If there is little or no condyle growth during treatment with appliances that displace the mandible, the result will be some degree of dual bite, with possible joint dysfunction. No growth during treatment with appliances that disclude but do not displace the mandible will result in little or no skeletal change, but with lingual tipping of the maxillary incisors and proclination of the mandibular incisors. 86 Thotllpso/l American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics January 1994 Fig, 2. Bolton standards from 1 to 18 years old. Taken from Bolton Standards, Kirtland Enterprises, Kirtland, Ohio. S t \ I a., 6 Fig. 4. Sicher's diagrammatic illustration of normal mandibular growth. I BRODIE Fig. 3. Brodie's illustration of enlarging facial pattern, with tracings of films made at birth, 3 years, and 8 years superimposed on the sella-nasion line. s My clinical research involving personal tracing of annual cephalometric radiographs on all orthodontically treated cases over a 40-year period has clearly shown that orthodontic treatment with either fixed or removable appliances will not cause the condyles to grow significantly. The inescapable conclusion is that despite often spectacular changes in the course of treatment by various means, treatment can neither start nor stop the growth of a mandible. Individual variability in timing and rate of growth. was very apparent in these studies. It must be concluded in the majority of cases that growth and treatment were independent, with concurrent changes the result of coincidence rather than cause and effect. Those cases with the better results had the benefit of good mandibular growth at the time of treatment, but orthodontic judgments must not be influenced only by these cases. Creekmore and Radney 9 make some significant merican Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 105,No. I Thompson 87 "olume tatements in their study of orthodontically treated cases nd untreated control cases. I. --individual growth responses were not prediclable. 2. --but looking at individual changes, we see tremeri'.ous variation. These are normal ANB angle changes that ,ccur in untreated persons. Is it no wonder, then, that the ame orthodontic treatment d6es not elici! the same response or all individuals since individuals do not grow the same vithout treatment?'6 Poulton I~ states~ "Upper faci.41 growth (S to N) was tot critical to treatment speed, but the fast ti'eating ~roup. averaged twice as much mandibular growth as he slow. This simply reconfirms what has been said :ountless times regarding the beneficial effects Of manlibular growth during thetreatment of Class II malocclusion. From the data recorded here, it would not De possible to predict When this growth would occur. f the study of various maturation criteria eventually eads to the prediction of facial growth, the efficiency if orthodontia treatment can be greatly increased." In 1956 Wylie H stated: "Growth, the best friend the irthodontist ever had, was all but driven out of the louse in the forties. Nineteen fifty-five would be an ,ppropriate yeai" to put a light in the window. Maybe he lady Growth will see it and come home again-his time to stay." Long-range cephalometric radio~raphic evaluation of orthodontically treated cases :learly sho,;vs that growth has "returned" in its proper ole of supporting treatment rather than as a variable esponsive to treatment. Weitimann and Sicher t have clearlyexplained the ,,rowth mechanisms of the facial structures. The maxIlary and mandibular teeth erupt vertically by growth ff the alveolar processes. This is appositional growth of bone tissue. The mandible and maxilla grow in size by appositional growth of bone tissue. The mandibular te6th are carried downward and forward with the body of the mandible by the upward and backward appositional growth Of the condylar cartilage tissue. This growth mechanism is uniquely characteristic of the mandible; long bones grow by the different mechanism of interstitial growth of cartilage. The maxillai'y teeth are concurrently carried downward and for~vard by sutural growth and alveolar bone growth. These two different mechanisms of growth, appoSitional cartilage growth in the mandibular condyle and sut/aral growth in the maxilla, are the basis for many disproportional relationships between the mandible and the maxilla. Overretraction of maXillary incisors can alter the occlusal position of the mandible, initially creating a functional retrusion and forcing the condyle to grow into posterior displacement. The rest position is not altered, so the normal rotary hinge closure from rest to occlusion becomes a translatory, bodily upward and backward path of closure because of incisal guidance, with clicking of the joints. It is often a matter of the relative timing of growth of the condyles and orthodontic treatment that determines the extent o f such lingual incisal movement. It is the interaction of the spatial relationships (position of the incisors) and time (growth of the condyle) that ultimately produces either conformity or disharmony (incisal interference). (This article will be continued in subsequent issues. References for tlre entire article will appear at the end of tlre third article.) Reprint requests to: Dr. John R. Thompson 3000 White Oaks Ln. Buchanan, MI 49107