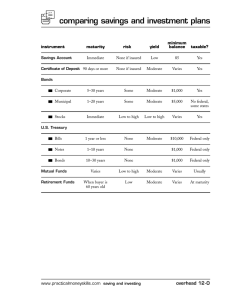

R E S E A R C H R E P O R T Pediatric Balance Scale: A Modified Version of the Berg Balance Scale for the School-Age Child with Mild to Moderate Motor Impairment Mary Rose Franjoine, MS, PT, PCS, Joan S. Gunther, PhD, PT, and Mary Jean Taylor, MA, PT, PCS Physical Therapy Program, Daemen College, Amherst, New York Purpose: The Pediatric Balance Scale (PBS), a modification of Berg’s Balance Scale, was developed as a balance measure for school-age children with mild to moderate motor impairments. The purpose of this study was to determine the test-retest and interrater reliability of the PBS. Methods: To determine test-retest reliability, 20 children (aged five to 15 years) with known balance impairments were tested by one examiner on the PBS. Ten pediatric physical therapists independently scored 10 randomly selected videotaped test sessions. Results: There was no significant difference in total test scores [intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) model 3,1 ⫽ 0.998] or individual items (Kappa Coefficients, k ⫽ 0.87 to 1.0; Spearman Rank Correlation Coefficients, r ⫽ 0.89 to 1.0) measured by one therapist on two occasions. No significant difference among ratings by different physical therapists was found on the PBS for total test score (ICC 3,1 ⫽ 0.997). Conclusion: The PBS has been demonstrated to have good test-retest and interrater reliability when used with school-age children with mild to moderate motor impairments. (Pediatr Phys Ther 2003;15:114 –128) Key words: child, posture, equilibrium, cerebral palsy, spinal dysraphism, mental retardation, activities of daily living, reproducibility of results, physical therapy techniques/methods INTRODUCTION AND PURPOSE Examination of balance is an important element of a physical therapy evaluation for a school-age child. The clinician must predict the ability of the child to safely and independently function in a variety of environments (ie, home, school, and community). Valid and reliable functional balance measures are of critical importance if the pediatric physical therapist is to justify that intervention is warranted and demonstrate that improved balance function has occurred as a result of intervention. Traditionally, pediatric physical therapists have examined balance through the observation of the underlying elements of the balance response, timed measures of static 0898-5669/03/1502-0114 Pediatric Physical Therapy Copyright © 2003 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Inc. Address correspondence to: Mary Rose Franjoine, MS, PT, PCS, Physical Therapy Program, Daemen College, 4380 Main St., Amherst, NY 14226. Email: mfranjoi@daemen.edu DOI: 10.1097/01.PEP.0000068117.48023.18 114 Franjoine et al postures, and standardized developmental measures of gross motor function.1– 4 The ability to describe the extent to which a child demonstrates righting reactions, protective responses, and equilibrium reactions in response to a therapist generated perturbation formed the foundation of the “classic” balance assessment.1,2 Traditional balance assessment also included timed measures of static sitting and standing balance including single limb stance.4 Standardized examination tools currently utilized by pediatric physical therapists for school-age children with mild to moderate motor impairment include the Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency,5 the Peabody Developmental Motor Scale,6 and the Gross Motor Function Measure.7 In addition, clinicians have developed their own non-standardized measures in an attempt to obtain information relative to the quality of performance during basic and instrumental activities of daily living, and higher-level gross motor tasks.4 The standardized and non-standardized measures that currently exist provide clinicians with valuable information, but may not fully meet their needs to assess a child’s functional balance abilities. Functional balance, for the purpose of this study, has been defined as the element(s) of postural control Pediatric Physical Therapy that allow a child to safely perform everyday tasks. A child of school age is expected to function independently within his/her home and school environment when performing self-help (basic activities of daily living), locomotor (mobility), and gross motor activities, including recreational activities/play (instrumental activities of daily living). As the child approaches adolescence and young adulthood increased proficiency in basic and instrumental activities of daily living is anticipated. Balance, the ability to maintain a state of equilibrium, is one of the critical underlying elements of movement that facilitates the performance of functional skills. Other critical elements for successful function include cognition, vision, vestibular function, muscle strength, and range of motion. The physical therapist must determine if the child possesses adequate functional balance to safely meet the demands of everyday life at home, in school, and within the community. School-age children with mild to moderate motor impairment pose unique challenges for the pediatric physical therapist. Generally, they have acquired basic motor abilities. At first glance, these children appear to possess the motor skills necessary for successful function within their homes, schools, and communities. They are able to ambulate independently with or without assistive devices. It is our observation, however, that a closer examination of their abilities reveals that they have a limited movement repertoire that allows for minimal variation of movement strategies within a given environment. Examples of such limitations include the ability to turn only in one direction in preparation to sit in a chair, or the ability to initiate single limb stance with only one limb in preparation for stepping onto a curb. Strong preferences or limited options may create movement strategies that are unique to given environments and appear slow, precarious, or impulsive. Children with mild to moderate motor impairment may appear to lack endurance for long duration/distance activities, such as standing still while waiting in a line. Standardized tests, such as the Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency,5 often reveal a significant delay in motor function for children with mild to moderate impairments compared to children of the same chronological age without impairments. Current standardized pediatric clinical measures may not provide the clinician with adequate information to fully assess a child with mild to moderate motor impairment’s functional balance. A review of balance in the literature suggested that the Berg Balance Scale (BBS) might be useful with the school-age population.8 –12 The 14 items contained within BBS (see Table 1) assess many of the functional activities a child must perform to safely and independently function within his/her home, school, or community: sitting balance, standing balance, sit to stand/ stand to sit, transfers, stepping, reaching forward, reaching to the floor, turning, and stepping on and off of an elevated surface. The test item “forward reaching” is conceptually similar to “functional reach,” which has been studied in the pediatric population.13 The purpose of this study was Pediatric Physical Therapy threefold: 1) to pilot test BBS for use with children; 2) to refine the instrument as needed for use with children; and 3) to determine test-retest and interrater reliability of the Balance Scale for school-age children with mild to moderate motor impairments. The BBS The BBS has undergone extensive reliability and validity testing within the geriatric patient population.8,10 The intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) for interrater and test-retest reliability for the test as a whole were 0.98 and 0.99, respectively. The ICC for individual test items ranged from 0.71 to 0.99. Berg has suggested that for older persons the Balance Scale is an appropriate screening tool with respect to functional balance, is predictive of future dysfunction, is sensitive to changes in functional balance skills, and may be used to monitor a patient’s status over time.9,10 The BBS is easy to administer, does not require specialized equipment, and can be completed in ⬍20 minutes. A 0 to 4 grading scale provides a quantitative and qualitative measure of performance. An overall numeric score is obtained at the conclusion of testing.10 METHODS Pilot Testing of the BBS with Children The BBS (see Table 1) was administered to 13 children who were typically developing who ranged in age from four to 12 years, on two separate occasions scheduled one week apart. A physical therapist (M.R.F.), a clinical specialist in pediatric physical therapy with 13 years of experience in school-based therapy, administered the BBS per test protocol to all 13 participants during both test sessions. The same test site was used for both test sessions. Preliminary results revealed unsatisfactory test-retest reliability. Formal statistical analysis of this data could not be completed as nine of the 13 participants (69%) had difficulty completing two or more of the test items that required prolonged maintenance of static postures. Marked variation within individual participant’s performance was noted from the initial test session to the follow-up test session with total test scores (TTS) decreasing by greater than six points in eight of the 13 (62%) participants. Issues associated with typical child behavior, attention span and following directions were consistently encountered throughout test administration during both sessions. On the basis of the results of pilot testing of the BBS with children who were typically developing, the 14 items contained within Berg’s scale were modified to create a pediatric version of this tool. The modifications were minor and included: 1) reordering of test items; 2) reducing time standards for maintenance of static postures; and 3) clarifying directions. Test items within the BBS are organized by increasing difficulty of task (see Table 1). In the pediatric version, items were reordered into functional sequences with novel tasks placed at the end of the scale (see Pediatric Balance Scale 115 Table 1). Time standards for BBS item 2, “standing unsupported,” item 3, “sitting unsupported,” and item 7, “standing unsupported feet together” were decreased to 30 seconds. In the BBS, a maximal score of “4” is earned in items 2 and 3 by maintaining a static posture for two minutes and in item 7 by maintaining a static posture for one minute. The scoring criteria to earn a “0” to “3” for each of these items were also modified. Directions and suggested equipment were modified throughout the balance scale. Examples include the use of footprints or a taped line to facilitate task completion in BBS items 2, 6 –10, 13, and 14. Equipment modification also included the use a child-size bench for BBS items 3–5, the use of a chalkboard eraser for BBS item 8, the use of a flash card for BBS item 10, and the use of a 6-inch step for BBS item 12. Care was taken to ensure that the intent of the items was not altered by the modifications. The Pediatric Balance Scale (PBS) and instructions for administration are presented in the Appendix. Pilot Testing of the PBS with Children The PBS, the revised version of the BBS, was administered per the protocol detailed in the Appendix, to 40 children aged five to seven years who were developing typically. They were recruited from two local elementary schools and participated in two separate test sessions scheduled two weeks apart for the purpose of determining test-retest reliability. Two entry-level physical therapy students (K.K. and J.L.) under the advisement of an experienced pediatric physical therapist (S.H.) administered and scored the test. Before test administration, the clinical specialist in pediatric physical therapy (M.R.F.) who participated in the initial pilot testing of the BBS with children who were typically developing and in the revision process to create the PBS, trained the two examiners. They participated in two three-hour training sessions, which concluded one week before their initial data collection session. Before the examiners completed their training, they demonstrated the ability to accurately administer and score the PBS for three children of varying ages. Their results revealed no significant difference for total test and retest scores of the 40 children who were developing typically on the PBS (p ⫽ 0.2489, Wilcoxon Matched Pairs Signed Ranks Test; r ⫽ 0.931, Spearman Signed Rank Correlation).14 The test-retest reliability was extremely high (ICC 3,1 ⫽ 0.850). Reliability of the PBS with Children with Mild to Moderate Motor Impairment Sample. Twenty children (12 boys and eight girls) ranging in age from five to 15 years (mean age nine years) with mild to moderate motor impairments were recruited for participation in this study from local elementary schools (see Table 2). The children were referred for participation in this study by their community-based physical therapist or their parent(s) or legal guardian(s). Informed consent was obtained before participation from the child’s parent(s) or legal guardian(s). A formal medical diagnosis was not considered essential for inclusion in this study. All children had a known functional limitation and/or disability that presented, clinically, as an impaired state of balance (disequilibrium). Etiologies of balance deficits varied among the participants and included neurological, musculoskeletal, and/or unknown causes (see Table 2). For inclusion in this sample, children had to be able to stand independently without upper extremity support for four seconds. All children who participated in this study were receiving physical therapy at the time of this study, although the amount of intervention varied from educational consult (one to three times per school year) to intensive outpatient physical therapy four times per week. (See Table 2) The children’s level of motor impairment also varied. Descriptions of the children provided by their physical therapists identified mobility skills, which ranged from independent community ambulation, without external assistive devices, to wheelchair dependent, able to ambulate for short distances. Children with a mental age of less than two years, attention deficit disorder, pervasive developmental delay, or a severe receptive language disorder were excluded from this study. The decision to exclude children from this study with significant cognitive, attention, behavioral, and/or language disorders was necessary because these disorders may severely compromise a child’s ability TABLE 1. The Berg Balance Scale and the Pediatric Balance Scale Berg’s Balance Scale Items 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 116 Franjoine et al Sitting to standing Standing unsupported Sitting unsupported Standing to sitting Transfers Standing with eyes closed Standing with feet together Reaching forward with outstretched arm Retrieving object from floor Turning to look behind Turning 360 degrees Placing alternate foot on stool Standing with one foot in front Standing on one foot Pediatric Balance Scale Items 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Sitting to standing Standing to sitting Transfers Standing unsupported Sitting unsupported Standing with eyes closed Standing with feet together Standing with one foot in front Standing on one foot Turning 360 degrees Turning to look behind Retrieving object from floor Placing alternate foot on stool Reaching forward with outstretched arm Pediatric Physical Therapy TABLE 2. Characteristics of children participating in this study and their total test scores for test and retest Subject Age in Years Gender Diagnosis Physical Therapy Sessions per Week Number of Days Between Test-Retest 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 9 6 7 13 9 13 5 11 7 8 7 8 10 15 14 5 5 14 9 10 Female Male Male Male Male Male Male Female Male Male Female Male Female Male Female Female Male Female Female Male PWS LD/SI CP-Hypo SB CP-SD MR Autistic CP-SD MR CP-ATHD CP-SD SP BT CP-SD CP-SD CP-SD CP-Hemi LD/SI CP-SD CP-SD CP-Hemi 2 2 2 CONSULT 2 1 2 2 3 4 3 2 4 3 4 2 2 3 2 2 7 14 7 7 7 9 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 10 8 7 10 7 7 7 Functional Level Mild Mild Mild Mild Mild Mild Mild Moderate Mild Moderate Mild Mild Moderate Moderate to Severe Moderate to Severe Moderate Moderate Moderate to Severe Moderate to Severe Moderate to Severe Test Session 1 TTS Test Session 2 TTS 45 45 46 48 47 52 44 42 49 31 46 52 34 19 8 14 30 13 13 5 45 41 41 48 46 52 46 42 49 31 46 52 34 19 8 14 30 13 13 5 PWS ⫽ Prader-Willi syndrome; LD/SI ⫽ learning disabled and speech-language impaired; MR ⫽ mental retardation; SB ⫽ spina bifida; SP BT ⫽ status post-brain tumor resection; CP ⫽ cerebral palsy; Athd. ⫽ athetoid; Hemi ⫽ hemiplegia; Hypo ⫽ hypotonia; SD ⫽ spastic diplegia; TTS ⫽ total test score. to comprehend and comply with test instructions in the standardized manner necessary for determining the reliability of a tool. Procedure Test-retest reliability. The PBS was administered to all 20 participants following the criteria set forth in Appendix 1. The same physical therapist (M.R.F.) tested all children at both test sessions. She was responsible for direct interaction with the child, administration of the test, scoring of the test, and ensuring the child’s safety during testing. An assistant was responsible for videotaping. Each item was scored on the criterion-based 0 to 4 scale. Only one practice trial per item was allowed. Verbal, visual, and physical cues were provided to ensure the child understood the requested task. If a child successfully completed the task (ie, scored a four on the first trial), additional trials were not administered. It took approximately 15 minutes to administer and score the PBS. A variety of test sites within the community were utilized in this study, including the child’s home, school, and private physical therapy clinic. For each child, the location of the test site for test one and two were the same. Selection of the test site was determined according to child, caretaker or clinician convenience. All children who participated in the study were scheduled for two test sessions that occurred within 14 days. Whenever possible, the day of the week and time of day were kept consistent. Scheduling of the test session was at the convenience of the child, their parent(s) or legal guardian(s), and/or the facility. Before each test session, a brief introductory period occurred. This period did not exceed 5 Pediatric Physical Therapy minutes, and was designed to put the child at ease, allowing the examiner to develop effective communication strategies with the child. The child’s parent(s) and the referring therapist(s) were invited to attend the test sessions. Interrater Reliability Interrater reliability of the PBS for total test score was determined by using the videotapes created during the test and retest data collection. Item 14, “forward reach,” was omitted from videotape analysis because a two-dimensional videotape does not adequately record test performance.13 To ensure a range of performance scores, videotaped test sessions were subdivided into three categories: TTS ⬍20, TTS ⱖ20 and ⬍40, and TTS ⱖ40. Three to four videotapes were randomly selected from the tapes in each category. Ten pediatric physical therapists with a minimum of two years of clinical experience participated in the interrater reliability phase of this study. All therapists were volunteers and were recruited from the local therapeutic community. Their level of pediatric clinical experience varied, ranging from two to 25 years (mean experience 9.4 years). All participating therapists were involved in pediatric clinical practice, although their practice setting varied: school-based, five therapists; outpatient hospital based, three therapists; outpatient private practice, two therapists. Each therapist participated in a single, 45minute training session on scoring of the PBS before scoring of the videotapes. The 10 therapists independently viewed and scored the 10 videotaped test sessions within one week of their training session. Pediatric Balance Scale 117 Analysis of Test-Retest Reliability To determine test-retest reliability of the PBS, scores on the initial administration of the PBS were compared with those obtained by the same investigator on the second administration of the PBS. Scores on the PBS are ordinal level data; therefore, the nonparametric Wilcoxon Matched Pairs Signed Ranks Test (alpha ⫽ 0.05) was used to test for significant difference between total test and total retest scores. The Kappa statistic, k, was used to evaluate the agreement of test and retest scores on individual test items. Each ordinal score from 0 to 4 was considered to be a category. The kappa corrects for the proportion of agreements between test and retest scores that occur as a result of chance.15 Correlation coefficients evaluate the correspondence between measurements. The correlation between test and retest scores was determined using the Spearman Rank Correlation coefficient. This test reflects the consistency of ranks of data, but not the degree of similarity between repeated test scores.15 An ICC model 3,1 [ICC(3,1)], which is a reliability coefficient based on an analysis of variance, was also determined. Analysis of Interrater Reliability A single-factor repeated-measure analysis of variance (alpha ⫽ 0.05) and an ICC(3,1) were used to evaluate interrater reliability of total test score (exclusive of item 14) on the PBS. RESULTS Test-Retest Reliability The age, gender, diagnosis, and frequency of physical therapy services as well as time between initial test and follow-up test are presented in Table 2 for all 20 children who participated in this study. The distribution of the TTS for test and retest data is also shown in Table 2. Individual TTS scores ranged from 5 to 52. The maximal possible TTS for the PBS is 56. There was no significant difference between total test and retest scores on the PBS (p ⫽ 0.2733, Wilcoxon Matched Pairs Signed Ranks Test). The test-retest reliability for individual items is presented in Table 3. k ranged from 0.87 to 1.0. The Spearman Signed Ranked Correlation, r, ranged from 0.89 to 1.0 for individual items. Test-retest reliability was extremely high [ICC(3,1) ⫽ 0.998]. Interrater Reliability Ten pediatric physical therapists with varied clinical background, including years of experience and practice setting, independently viewed and scored the videotaped performance of 10 children. The median, mode, and range of TTS on the PBS for each of the videotaped subjects are presented in Table 4. The total test scores of the subjects examined by the 10 therapists ranged from five to 49 with only a zero-to-two point difference in the total test scores for each subject. There was no significant difference among ratings by different physical therapists on PBS TTS (F ⫽ 118 Franjoine et al TABLE 3. Test retest reliability item analysis 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. PBS Test Items Kappa Spearman Sit-Stand Stand-Sit Transfers Standing Balance Sitting Balance Stand Eyes Closed Stand Feet Together Stand One Foot in Front-Tandem Stand on One Foot Turn 360 Degrees Turn and Look Behind Pick Up Object Stepping Functional Reach 1.00 1.00 1.00 0.92 1.00 1.00 0.91 0.92 1.00 1.00 1.00 0.89 1.00 1.00 0.99 0.96 0.87 0.91 0.93 1.00 0.93 1.00 0.95 0.99 1.00 0.93 1.00 1.00 PBS ⫽ pediatric balance scale. 1.574; p ⫽ 0.1087) (see Table 5) and high interrater reliability was demonstrated via an ICC(3,1) ⫽ 0.997. DISCUSSION Preliminary testing of the PBS reveals very high testretest and interrater reliability for children five to 15 years of age with mild to moderate motor impairments. The PBS may therefore provide clinicians with an additional, reliable means of assessing a child’s balance. The PBS also affords clinicians a standardized protocol for test administration and scoring. Our preliminary work does not specifically address the validity of the PBS as a pediatric balance measure, nor does it provide normative information. Clinical observations support the content (face) validity of the PBS, because items contained within are routinely performed by children throughout the day and are frequently examined by pediatric physical therapist as a component of assessment. Examples of such tasks include the following: item 1, sit to stand; item 2, stand to sit; item 10, turning around; item 11, turning to look behind; and item 12, picking an object up from the floor (see the Appendix and Table 1). The PBS incorporates a 0 to 4 grading scale to assess performance. The scoring criterion within an item incorporates qualitative and quantitative measures that allow for TABLE 4. Median, mode and range of TTS on PBS for 10 subjects evaluated by 10 pediatric physical therapists Subjects Median Mode Range 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 5 12 12 27 11 31 49 45 40 43 5 12 12 27 11 31 49 45 40 43 1 0 0 0 0 1 2 1 1 0 Pediatric Physical Therapy TABLE 5. Summary table for single-factor repeated-measures analysis of variance: PBS total scores of 10 videotaped subjects scored by 10 pediatric physical therapists Subjects (S) Therapists (T) Error (S ⫻ T) df Sum of Squares Mean Square F Value p Value 9 9 81 24430.800 1.600 8.600 2714.533 0.178 0.106 1.674 0.109 normal variability in performance. This aspect of the grading scale is extremely important, in that variability is a hallmark of typical motor development. PBS item 8, “standing one foot in front” (see Appendix) illustrates the use of qualitative measures, quantitative measures and variability within the scoring criteria of a single item. This item examines a child’s ability to assume and maintain a tandem posture. To obtain the maximal score of four the child must be able to independently assume a tandem foot placement position and maintain it for 30 seconds. A lesser score is earned if the child requires assistance to step, can maintain a stride stance, but not tandem stance, or maintains the tandem posture for ⬍30 seconds. Extreme care was taken during the modification process of the BBS to ensure that the intent of the task was not altered. The reduction in time parameters for static stance in BBS items 2, 3, and 7 was necessary to ensure the measure of elements of postural control vs attention span. The reduction to 30 seconds may limit the ability of this tool to assess the underlying element of muscle strength/postural stability as a component of functional balance. The time parameter of 30 seconds was chosen based in part upon clinical observation during pilot testing of the BBS and current clinical research in the area of pediatric balance.1,4 Care was taken to limit the effects of learning during the test-retest phase of this study. Verbal, visual, and tactile feedback, for each item, was provided during test session one and two during the practice trial only. Qualitative performance feedback, positive or negative, was not provided during test administration and/or scoring. Additional feedback relative to individual item(s) or overall task performance was also not provided. At the conclusion of each test the child received a small toy of their choice as a thank you for participating. The test and retest session were scheduled at least seven days apart and no longer than 14 days to minimize the effects of leaning, retention, and developmental-based changes. The PBS has limitations. For example, the PBS does not examine a child’s ability to reach overhead. If one considers the strategies that children use as they interact with their environment, we have observed that items which are out of reach are frequently overhead. Additionally, the PBS does not examine issues associated with balance during locomotion. Inclusion of such items in the PBS would require further investigation. Several questions remain with respect to the validity of the PBS. Does the TTS have meaning, and if so, what does it mean? Do age, height, weight, or gender influence test performance? Is the PBS sensitive to functional Pediatric Physical Therapy change? Is it capable of documenting skill progression or regression over time? Do the criteria used in the grading scale reflect different levels of motor proficiency? Are the scale increments (zero to four) reflective of an overall change in function? Ongoing investigation with the PBS includes collection of normative data on children who are typically developing. Preliminary results suggest that children who are typically developing by the age of seven years can successfully complete all items within the PBS, obtaining the maximal score of 56. Additionally, three subjects have been tested using the PBS for a period of two years in conjunction with their ongoing clinical intervention programs. Trends in their data suggest that the PBS may be sensitive to changes in a child’s functional balance abilities over time. It is hoped that the PBS can be used clinically to screen for functional balance deficits, identify a need for physical therapy intervention, and to monitor progress within a therapeutic program. CONCLUSION Preliminary data supports the use of the PBS as a reliable measure of functional balance for use with the schoolage child with mild to moderate motor impairment. It is quick to administer and is easily scored. Total test administration and scoring time is ⬍15 minutes. The PBS does not require the use of specialized equipment. It provides clinicians with a standardized format for measurement of functional balance tasks which are routine components of physical therapy examination for the school-age child with mild to moderate motor impairments. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors thank the children, their families, and the community clinicians who participated in this study. The authors acknowledge and thank Sharon L. Held, MS, PT, PCS, Kim Kobes, PT, and Jeff Lach, PT, for their contributions to this study. A special thank you is extended to Katherine Carey Carney, Theresa Kolodziej, Deborah Scheider, and Jane Montgomery for their assistance and support. This study is dedicated in loving memory of Gregory James Heiser (November 9, 1988 to August 23, 1996). Sleep well my little angel. REFERENCES 1. Woollacott MH, ed. Development of Posture and Gait Across the Life Span, 2nd ed. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press; 1989. Pediatric Balance Scale 119 2. Fisher AG. Objective assessment of the quality of response during two equilibrium tasks. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 1989;9:57–78. 3. Pountney TE, Mulcahy C, Green E. Early development of postural control. Phys Canada. 1990;76:700 – 802. 4. Westcott S, Lowes LP. Assessment and treatment of balance dysfunction in children. (unpublished) 1995; APTA Combined Sections Meeting: Pediatric Section Pre-Conference Course. 5. Bruininks RH. Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency Manual. Circle Pines, Minn: American Guidance Services, Inc.; 1978. 6. Folios MR, Fewell RR. Peabody Developmental Motor Scales and Activity Cards. Chicago, Ill: Riverside Publishing Company; 1983. 7. Russell D, Rosenbaum P, et al. Gross Motor Functional Measure Manual, 2nd ed. Hamilton, Ontario, Canada: Gross Motor Measure Group; 1993. 8. Berg K, Maki BE, Williams JI, et al. Clinical and laboratory measures of postural balance in an elderly population. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1992;73:1073–1080. 120 Franjoine et al 9. Berg K. Balance and its measure in the elderly: a review. Phys Canada 1989;41:240 –246. 10. Berg K, Wood-Dauphinee S, Williams JI, et al. Measuring balance in the elderly: preliminary development of an instrument. Phys Canada. 1990;41:304 –311. 11. Di Fabio RP, Badke MB. Relationship of sensory organization to balance function in patients with hemiplegia. Phys Ther. 1990;70:542–548. 12. Shumway-Cook A, Horak FB. Assessing the influence of sensory interaction on balance. Phys Ther. 1986;66:1548 –1550. 13. Donahoe B, Turner D, Worrell T. The use of functional reach as a measurement of balance in boys and girls without disabilities ages 5 to 15 years. Pediatr Phys Ther. 1994;6:190 –193. 14. Kobes K, Lach J. Determining the Intertester and Intratester Reliability of the Pediatric Balance Scale for Normal Developing Children. Amherst, NY: Daemen College, 1997. Bachelor’s Thesis. 15. Portney LG, Watkins MP. Foundations of Clinical Research. Norwalk, Conn: Appleton & Lange; 1993. Pediatric Physical Therapy APPENDIX Pediatric Physical Therapy Pediatric Balance Scale 121 122 Franjoine et al Pediatric Physical Therapy Pediatric Physical Therapy Pediatric Balance Scale 123 124 Franjoine et al Pediatric Physical Therapy Pediatric Physical Therapy Pediatric Balance Scale 125 126 Franjoine et al Pediatric Physical Therapy Pediatric Physical Therapy Pediatric Balance Scale 127 128 Franjoine et al Pediatric Physical Therapy