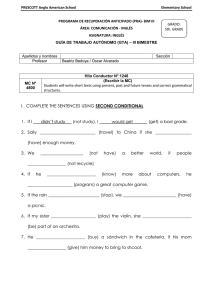

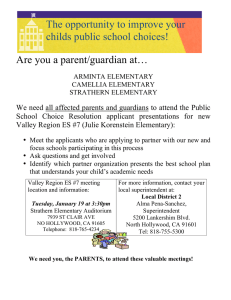

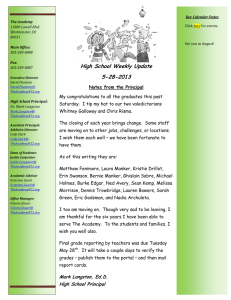

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329799403 Elementary Student Perceptions of School Climate and Associations With Individual and School Factors Article · December 2018 CITATIONS READS 2 785 3 authors: Tamika La Salle Faith Zabek University of Connecticut Georgia State University 16 PUBLICATIONS 94 CITATIONS 8 PUBLICATIONS 12 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Joel Meyers Georgia State University 122 PUBLICATIONS 2,355 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: International Journal of School and Educational Psychology View project School Psychology International View project All content following this page was uploaded by Tamika La Salle on 20 December 2018. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. SEE PROFILE VOLUME 10 ? ISSUE 1 ? PAGES 55–65 ? Spring 2016 Elementary Student Perceptions of School Climate and Associations With Individual and School Factors Tamika P. La Salle University of Connecticut Faith Zabek Joel Meyers Georgia State University ABSTRACT: School climate has increasingly been recognized as an essential component of school improvement owing to the established associations between a positive school climate and academic outcomes for students. Our study examines associations among a brief measure of school climate assessing elementary student perceptions and the College and Career Ready Performance Index, Georgia’s comprehensive school improvement and accountability index. Individual factors including student grade, race/ ethnicity, and gender were also examined in relation to perceptions of school climate. Multilevel analyses and hierarchical linear modeling indicated that student-level variables accounted for the majority of variation in perceptions of school climate. Notably, results revealed a significant and negative interaction among school climate, school achievement, and gender. These findings suggest that personal characteristics have a notable impact on students’ experiences and perceptions of climate and should be considered in the development and implementation of school climate improvement efforts. School climate has become an increasingly important area among researchers and school personnel owing to its demonstrated connections to social, emotional, and academic outcomes. Several studies have confirmed the reciprocal link between a positive school climate and academic success. For example, school climate has been positively associated with motivation to learn (Eccles et al., 1993), total school achievement (Brookover et al., 1978), grade point average (Buckley, Storino, & Sebastiani, 2003), student engagement (Skinner & Belmont, 1993), attendance (Gottfredson & Gottfredson, 1989), and graduation rates (Thapa, Cohen, Guffey, & Higgins-D’Alessandro, 2013). The National School Climate Council (2007) defines school climate as follows: “School climate is based on patterns of people’s experiences of school life and reflects norms, goals, values, interpersonal relationships, teaching and learning practices, and organizational structures” (p. 4). In addition, Cohen, McCabe, Michelli, and Pickeral (2009) identified the following four aspects of the school environment that affect the climate within a school: Safety, Relationships, Teaching and Learning, and the Environment/Structure. Contained within each dimension, are various subdimensions or elements of school climate. The subdimensions within Safety include physical and social– emotional safety as well as related rules and attitudes. The area of Relationships contains elements such as respect for diversity, morale, and leadership. The elements of Teaching and Learning may be Correspondence concerning this article should be directed to Tamika P. La Salle, Department of Educational Psychology, 249 Glenbrook Rd., Unit 3064, Storrs, CT 06269; tamika.la_salle@uconn.edu. Copyright 2016 by the National Association of School Psychologists, ISSN 1938-2243 the most commonly associated with schools and educational outcomes, and these elements include quality of instruction and social, emotional, and ethical learning. Last, contained within the Environmental/Structural dimension of school climate are subdimensions such as cleanliness, the physical layout of the school, and extracurricular activities. More recently, Thapa et al. (2013) highlighted another key component of school climate: the role of school climate in the school improvement process. A school’s climate influences the implementation and efficacy of improvement efforts (Bryk, Sebring, Allensworth, Luppescu, & Easton, 2010). In addition, whole school climate improvement efforts “may powerfully influence the prevention of socioemotional, behavioral, and academic difficulties” (Felner et al., 2001, p.177) and support successful student development and outcomes. This recognition of school climate as an essential component of school improvement is timely given the rise of initiatives to increase school climate accountability through federal grant opportunities (e.g., school climate transformation grants, safe and supportive school grants) and statewide efforts to measure this construct (e.g., California Healthy Students Survey, [Furlong, Greif, Bates, Whipple, & Jimenez, 2005], Delaware School Climate Survey [Bear, Gaskins, Blank, & Chen, 2011], Georgia Student Health Survey [White, LaSalle, Ashby, & Meyers, 2013], Georgia School Climate Star Rating Index). The state of Georgia represents one example of such statewide efforts to integrate school climate as part of an accountability and school improvement tool. In 2014, Georgia began including a School Climate Star Rating Index alongside its annual accountability platform, the College and Career Readiness Performance Index. The School Climate Star Rating was developed to provide feedback to schools about a number of school climate–related variables (e.g., school climate, school safety, school attendance) to inform their school improvement processes. Given these new initiatives that, in part, rely on school climate data as a school accountability measure, it is important that researchers investigate relationships between these measures and outcome factors such as student achievement. Our study investigates that relationship within elementary schools in Georgia. ELEMENTARY STUDENT PERCEPTIONS OF SCHOOL CLIMATE At the elementary level, researchers have found school climate to relate positively with school achievement (Brookover et al., 1978; Johnson & Stevens, 2006) above and beyond student demographic variables. In fact, after removing the effect of school climate, Brookover et al. (1978) found that school composition variables such as socioeconomic status and racial composition explained little variance in mean school achievement. These positive academic outcomes associated with school climate persist over time and relate to future academic success (Hamre & Pianta, 2001; Hoy, Hannum, & TschannenMoran, 1998). For example, Hamre and Pianta (2001) found that observed emotional support within elementary school classrooms predicted future academic success, even after controlling for current achievement level. This suggests that a positive school climate in elementary school may encourage the development of skills needed for academic success later in life. Our study aims to add to the literature linking school climate to academic achievement. Research considering school climate at the elementary school level has largely focused on teacher perceptions rather than student perceptions of climate (Johnson & Stevens, 2006). This reliance on teacher report rather than student report for elementary school students may be due to the advanced cognitive abilities required to accurately complete self-report measures (Merrell, 2003). However, students “are the best source of information for rating their inner feelings” (Merrell, 2003, p. 486), and it is important to consider the students’ perceptions using developmentally appropriate self-report measures. Given that teachers and students do not always perceive climate similarly (Mitchell, Bradshaw, & Leaf, 2010), inclusion of student perceptions is a critical component of assessing school climate. Also, social– ecological theory suggests that individuals’ perceptions, rather than others’ perspectives or some objective reality, are critical for understanding their behavior (Bronfennbrenner, 1979; Haynes, Emmons, & Ben-Avie, 1997; Kuperminc, Leadbeater, Emmons, & Blatt, 1997). Therefore, students’ own perceptions of climate should be considered when investigating links between school climate and outcome factors, NASP | School Psychology Forum: Research in Practice Elementary Perceptions of School Climate | 56 such as student achievement. In addition, examining changes in perceptions of school climate across important school-age transitions (e.g., as students progress through elementary school) may help us better understand how these transitions affect student perceptions and behaviors. In a review of school climate literature, Thapa et al. (2013) summarized late elementary school as a “natural window of opportunity for antibullying and upstander interventions” (p. 363) because students within that age group begin to make ethical judgments about group norms and peer behaviors. Consequently, in order to inform positive school climate strategies and interventions, one of the aims of our study is to provide support for a psychometrically sound measure of elementary school students’ perceptions of school climate that can be used to investigate students’ perceptions of climate. When investigating relationships between school climate and outcomes, it is important to recognize that student perceptions of school climate are influenced by personal characteristics and individual factors, such as gender, grade, and race/ethnicity (Brookover et al., 1978; Koth, Bradshaw, & Leaf, 2008; Thapa et al., 2013; Wilson, Pentecoste, & Bailey, 1984). For example, Koth et al. (2008) found that male and ethnic minority students tend to report less favorable perceptions of school climate. Watkins and Aber (2009) confirmed that ethnic minority students, specifically Black students, perceived a more negative climate than their White counterparts. However, contrary to Koth et al. (2008), they discovered that female students reported a more negative climate than male students. Studies examining perceptions of school climate among elementary students have often used long selfreport forms such as the school climate measures mentioned earlier that are used in Delaware and California, the Comer School Development Program Climate Survey (Haynes, Emmons, Ben-Avie, & Comer, 2001), and the Comprehensive School Climate Survey (Stamler, Scheer, & Cohen, 2009). Though extended surveys can be effective in guiding school improvement efforts, using a brief measure of school climate at the elementary level may be more likely to obtain accurate results among an upper elementary age range, as longer measures require sustained attention, which may tax these students’ reading and cognitive skills. There is a need for such a measure of school climate (e.g., White et al., 2014) that addresses the dimensions described in Cohen et al. (2009) and is designed to assess upper elementary school students’ perceptions using readability levels that are accessible to a wide range of students. Our study presents the Georgia Elementary School Climate Survey as a brief measure of school climate used to assess upper elementary students’ perceptions of school climate. The purpose of our study is to (a) present a brief elementary school climate survey reflective of current dimensions of school climate for students in fourth and fifth grade; (b) investigate the relationship between the Georgia Elementary School Climate Survey and student race/ethnicity, gender, and grade; (c) investigate the relationship between the Georgia Elementary School Climate Survey and school College and Career Readiness Performance Index scores; and (d) investigate the interaction effects of student demographics on the relationship between the Georgia Elementary School Climate Survey and school College and Career Readiness Performance Index scores. METHODS The Georgia Elementary School Climate Survey was administered during the 2013–2014 school year to fourth- and fifth-grade students throughout the state of Georgia. Passive consent procedures were used, and data were collected anonymously and received in de-identified form from the Georgia Department of Education. A university institutional review board approved all procedural protocols before data were obtained. A total of 197,512 fourth- and fifth-grade students participated, representing 1,073 of the 1,325 elementary schools in the state of Georgia. This sample included 49.7% females and 50.3% males and 50.4% fourth graders and 49.6% fifth graders. Participants represented the following ethnic backgrounds: 41.9% White, 35.9% Black/African American, 12.8% Latino/Hispanic, 5.7% Other, and 3.7% Asian or Pacific Islanders (see Table 1). NASP | School Psychology Forum: Research in Practice Elementary Perceptions of School Climate | 57 Table 1. Sample Demographics and Means Grouping Variable Gender Grade Race/ethnicity Sample Population Girls Boys Fourth Fifth White Minority Study Demographics 41.9% 58.1% 50.4% 49.6% 41.9% 58.1% Total School Climate M(SD) 3.25 3.19 3.23 3.19 3.26 3.19 3.22 (.45) (.48) (.45) (.47) (.44) (.48) (.47) CCRPI 76.18 (12) Note. CCRPI, College and Career Readiness Performance Index. Measures Georgia Elementary School Climate Survey: The Georgia Elementary School Climate Survey is a self-report scale intended to measure upper elementary students’ perceptions of school climate. The survey was developed by the Georgia Department of Education, in collaboration with the Center for Research on School Safety, School Climate, and Classroom Management at Georgia State University and the University of Connecticut. The elementary version of the survey was adapted from the Georgia Brief School Climate Inventory (White et al., 2014) to be suitable for upper elementary school students in grades 3–5. However, the focus of our study is on students in fourth and fifth grade. Both the Georgia Brief School Climate Inventory and the Georgia Elementary School Climate Survey were designed to assess students’ overall perceptions of school climate through a brief survey format. The Georgia Elementary School Climate Survey includes 11 items (see Table 2) of school climate (see Cohen et al., 2009, for a full review). The Georgia Elementary School Climate Survey also includes the following three demographic questions: race/ethnicity, gender, and grade. The sample average for school climate was 3.22 (SD 5 .47). Table 1 includes sample means and standard deviations by demographic subgroup. Table 2. Georgia Elementary School Climate Survey: Items and Factor Loadings Item Factor Loading I like school. I feel like I do well in school. My school wants me to do well. My school has clear rules for behavior. I feel safe at school. Teachers treat me with respect. Good behavior is noticed at my school. Students in my class behave so that teachers can teach. I get along with other students. Students treat each other well. There is an adult at my school who will help me if I need it. .492 .315 .452 .464 .658 .515 .440 .635 .498 .572 .481 NASP | School Psychology Forum: Research in Practice Elementary Perceptions of School Climate | 58 College and Career Readiness Performance Index. This index, at the elementary school level, represents a school’s level of improvement and students’ preparedness for the future. The following performance indicators are included: (a) Achievement points, (b) Achievement Gap points, and (b) Progress points. A school may also earn Exceeding the Bar points if they have a Georgia Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math program certification, a fitness program assessment, or innovative practices to document student achievement. The College and Career Readiness Performance Index scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing greater school achievement. The Georgia Department of Education reports College and Career Readiness Performance Index scores on an annual basis. The sample mean for the index was 76.18 (SD 5 12). Analyses During the preliminary analysis stage, confirmatory factor analyses were conducted in Amos 22 to confirm the factor structure of the Georgia Elementary School Climate Survey. Confirmatory analysis was selected because the Georgia Elementary School Climate Survey was adapted from the middle and high school Georgia Brief School Climate Inventory, which has been previously validated (White et al., 2013). The confirmatory factor analysis results indicated good model fit between the model and the data: x2 (39) 5 18163.445, p , .001; root mean square error of approximation, .048; standardized root mean square residual, .03; comparative fit index, 0.99; and Tucker Lewis Index, .941 (Haynes, Comer & Hamilton-Lee, 1989). The internal consistency of the scale was .8. The mean score for school climate was 3.22 (SD 5 .46) for the total sample. Table 1 includes the mean score and standard deviations by grade, race/ethnicity, and gender. Prior to hierarchical linear and nonlinear modeling (HLM) model building, each variable within the data set was reviewed to ensure that there was not a systematic pattern of missing data or outliers. Given that missing level 2 variables cannot be accommodated by HLM, schools that were missing College and Career Readiness Performance Index scores were not included in the analyses. Descriptive statistics were inspected in order to examine normality of data for all variables. There was no evidence to suggest that the assumption of normality had been violated. Scores for each variable were normally distributed and skewness and kurtosis values for each variable were within acceptable ranges (+/2 2; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) suggesting that assumptions of normality were not violated. The variable of school climate was negatively skewed and kurtotic. However, scatterplots for the variables indicated normal distribution as well. Maximum likelihood estimates with robust standard errors were used to estimate the parameters. The overall fit of the model was evaluated on the basis of the likelihood ratio test (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). Multivariate Results A multilevel modeling approach was used to examine the main hypothesis using HLM 6.0 due to the nested structure of the data with students (N 5 197,745) nested within schools (N 5 1,078). Consistent with previous research (Koth et al., 2008), we hypothesized that a substantial portion of the variance in perceptions of school climate would exist at the student level and that differences in school climate perceptions would be explained, in part, by demographic characteristics. We also hypothesized that the clustering of students within schools would account for a smaller, but noteworthy, portion of the variance in school climate perceptions. Further, we hypothesized that school College and Career Readiness Performance Index scores would be associated with perceptions of school climate. Multilevel analyses were selected because both the data (students nested within schools) and the research question (the impact of student and school-level variables on perceptions of school climate) are nested and multilevel in nature (Koth et al., 2008, p. 99; Raudenbush and Bryk, 2002). In other words, there is an assumption that students within the same school have overlapping variance, and multilevel models account for the nonindependence of observations, allowing for correlated error structures. NASP | School Psychology Forum: Research in Practice Elementary Perceptions of School Climate | 59 To estimate the effect of student perceptions clustered within schools, we estimated a two-level hierarchical linear model using HLM 7 software (Raudenbush et al., 2011). Outcome data (perceptions of school climate) were measured at the student level, level 1. Additional student (level 1) indicators included student race/ethnicity, grade, and gender. At the school level (level 2) one indicator was estimated, school College and Career Readiness Performance Index scores. During each stage, student and school-level variables were inspected individually to assess the significance of the residual variance. Model assumptions were checked after each outcome. RESULTS Using HLM 7 (Raudenbush et al., 2011), the variance in perceptions of school climate for each level (student and school) was calculated for the unconditional model (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). Unconditional Model Intraclass correlations from the unconditional model indicated that the variation in perceptions of school climate between students and across schools was significant. Specifically, 93% of the variance in perceptions of school climate was explained by between-student variation (i.e., at the student level). School-level variables (the clustering of students within schools) accounted for the remaining 7% of variance. Multivariate Results A series of regression analyses examining the relationships between student and school-level variables and school climate were estimated. Each model was clustered on schools (n 5 1073) to estimate the standard errors. All of the observed relationships among student level, gender, grade, and race/ethnicity, and perceptions of school climate were significant. For example, perceptions of school climate decline slightly between fourth and fifth grade and girls report higher perceptions of school climate than boys. Results also indicate that White students report more favorable perceptions of school climate than students identifying as an ethnic minority. However, beta weights for significant variables were small, so the magnitude of differences between groups should be interpreted with caution. For the level 2 (school) model, the effect of school College and Career Readiness Performance Index scores on student perceptions of school climate was estimated. School College and Career Readiness Performance Index scores (centered around the grand mean) were significantly related to the outcome variable. As College and Career Readiness Performance Index scores increased, so did perceptions of school climate. Multilevel model estimates for the outcome variable are displayed in Table 3. In the final model, both student and school-level predictors were included to examine possible interaction effects. After controlling for student (i.e., gender, grade, and race/ethnicity) and school (i.e., College and Career Readiness Performance Index) covariates, variation in perceptions of school climate across race/ ethnicity, grade, and gender remained significant at the intercept. The effect of gender, race/ethnicity, and grade was negative for males, ethnic minority students, and fifth-grade students, respectively, when compared to their counterparts. Further, significant interaction effects were observed among College and Career Readiness Performance Index scores, climate, and gender. Specifically, for gender, the interaction effect indicated perceptions of school climate continue to decrease even as school College and Career Readiness Performance Index scores increase among both males and females, but the effect is more negative for males. There were no significant interaction effects between school climate, College and Career Readiness Performance Index, race/ethnicity, or grade. NASP | School Psychology Forum: Research in Practice Elementary Perceptions of School Climate | 60 Table 3. Multilevel Results for School Climate Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Variables Coefficient SE T Gender Gender 6 CCRPI grade Grade 6 CCRPI race/ethnicity CCRPI Gender Gender 6 CCRPI grade Grade 6 CCRPI Race/ethnicity Race/ethnicity 6 CCRPI 2.06** .002 221.68 2.05** .005 212.87 2.03** .004** 2.057** 2.004* 2.052** .003 .000 .003 .000 .004 229.05 12.727 221.08 22.118 212.73 2.024** 2.001 .003 .000 26.827 21.9 **p , .001; *p , .01. Note. CCRPI, College and Career Readiness Performance Index. Model Fit A series of fit indices were calculated to evaluate the fit of the data to the final model. A likelihood ratio test is used to assess the goodness-of-fit between nested models. We examined difference in deviance values between the final model (inclusive of all level 1 and level 2 predictors) and the student model (containing age, grade, and race/ethnicity covariates) and difference in deviance values between the final model and the school model (containing the College and Career Readiness Performance Index as a covariate) to determine whether the more complex (final model with all covariates) significantly reduced the baseline deviance from the student-only and school-only models. The reduction of deviance from the student-only model to the final model was significant (x2 (4) 5 151.46, p , . 01) and the school only model to the final model (x2 (6) 5 1583.92, p , . 01) was significant suggesting that the more complex model with more predictors represents better model fit. DISCUSSION The purpose of our study was to present a brief elementary survey assessing upper elementary students’ perceptions of school climate. The purpose was also to examine the relationships between student and school variables on upper elementary school students’ perceptions of school climate using a multilevel framework. Specifically, student demographic variables including grade, race/ethnicity, and gender were explored. At the student level, school College and Career Readiness Performance Index scores, representing the Georgia school comprehensive performance index, were examined in relation to climate and student variables to explore previously identified relationships. The unconditional model indicated that the majority of variance in elementary student perceptions of school climate is accounted for by student-level variables including gender, race/ethnicity, and grade (93%). At the school level, school College and Career Readiness Performance Index scores accounted for an additional 7% of the variance in perceptions of school climate. NASP | School Psychology Forum: Research in Practice Elementary Perceptions of School Climate | 61 Individual Level Variables Student grade, gender, and race/ethnicity were significantly related to student perceptions of school climate in directions that are consistent with prior research (Koth et al., 2008; Kuperminc et al., 1997). Males and ethnic minority students reported less favorable perceptions of school climate in comparison to girls and White students, respectively. Further, fourth-grade students reported higher perceptions of school climate than fifth-grade students. These findings illustrate that personal characteristics often have a notable impact on student’s educational experiences and perceptions of school climate. They also support the need to identify strategies and interventions that promote positive school climates as well as targeted systems of support for students at risk of experiencing lower perceptions of school climate and adverse student outcomes. School Variables School performance, as accounted for by College and Career Readiness Performance Index scores, was significantly and positively related to student perceptions of school climate, though the effects were smaller than expected (Brookover et al., 1978; Koth et al., 2008). Still, results of the study demonstrate that the revised metric of school performance, the College and Career Readiness Performance Index, is significantly related to student perceptions of school climate. Overall, these findings suggest that on average, as College and Career Readiness Performance Index scores increase, so do student perceptions of school climate. Interaction Effects A unique finding of our study was the interaction of school performance with both gender and perceptions of climate. Contrary to expectations, there was a negative relationship between school performance and gender. Specifically, as school College and Career Readiness Performance Index scores increased, perceptions of school climate decreased for both groups and more so for males. These findings are preliminary and may be further clarified by additional variables that can have a negative impact on boys’ perceptions of school climate when academic performance increases. Examples of variables that might have a positive or protective effect include positive teacher–student interactions (Osterman, 2000), support, sense of connectedness and belonging (McNeely, Nonnemaker, & Blum, 2002), and attitudes about their teacher (Koth et al., 2008). Factors that may have a negative effect may include peer victimization (Sulkowski, Bauman, Dinner, Nixon, & Davis, 2014) or negative perceptions about academics (Brookover et al., 1978). Though conclusions about the variables that may affect perceptions of climate for the at-risk groups cannot be drawn from a single study, these findings suggest the need for additional research exploring relationships between student and school variables that may result in negative perceptions of climate within high-achieving schools. LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH Our study presents the Georgia Elementary School Climate Survey, a brief, yet representative, measure of school climate that can be administered to upper elementary students to gather perceptions of school climate. Evidence of the relationships between perceptions of school climate and both student (level 1) and school (level 2) variables were also presented. Still, there are several limitations of the study that should be noted. First, the sample was limited to elementary students in one southeastern state. Future studies should be conducted with various populations to determine whether the findings in our study are replicated among other samples of elementary school students. Also, while the effects of student and school variables on perceptions of school climate were significant, they were small and should be interpreted with caution. Both the Georgia Elementary School Climate Survey and the College and Career Readiness Performance Index are novel measures that can be used for research on school accountability and school improvement. Preliminary data analyses presented in our study suggest that they represent NASP | School Psychology Forum: Research in Practice Elementary Perceptions of School Climate | 62 the constructs that they are intended to measure and may be used to clarify the relationships between school climate, student variables, and achievement. Still, future research is warranted to further confirm the validity of the measures. IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE School psychologists often play a pivotal role in school improvement efforts. Understanding the nature of relationships between student and school factors and student perceptions of climate is essential to their ability to identify strategies and preventative programs aimed at promoting a positive school climate; identify students who are at risk of experiencing a negative school climate; and implement additional, targeted supports to assist students in need. Our study provides evidence that in addition to using school climate data to enhance school-wide reform efforts directed to climate improvement, school psychologists should also pay particular attention to students who may be at increased risk of negative perceptions of school climate and poor student outcomes. Examples of groups warranting this kind of attention are boys, ethnic minority students, and students transitioning across grades. School psychologists can also play a role to ensure that factors in the educational environment (e.g., student– teacher interactions, student engagement) are effective for all students and targeted to meet the needs of whole groups (school wide) and subgroups (e.g., males). School climate continues to stand out as having a notable impact on student outcomes. Our study continues to support these claims using a brief elementary school climate survey for upper elementary student perceptions. Findings from our study support the need of school psychologists and educators to attend to and recognize that student perceptions of school climate vary, even for upper elementary school students. Particular attention should be focused on efforts to promote positive school climates for all students, recognizing students who might require additional supports. Years of research have provided significant evidence indicating that if we want students to do well academically, we must also recognize and attend to students’ social–emotional needs. Such considerations are especially important given the increased pressure from federal and state educational agencies requiring districts and schools to monitor school climate and school climate improvement efforts. Perceptions of school climate, as gathered through a valid, brief survey is a starting point. The Georgia Elementary School Climate Survey can help school personnel understand how elementary students feel about the school environment and can guide targeted intervention efforts that facilitate a positive school climate. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION Obtain additional information about the Georgia Elementary School Climate Survey by contacting Tamika P. La Salle at the University of Connecticut: http://education.uconn.edu/tamika-la-salle/ REFERENCES Anderson, G. J. (1973). The assessment of learning environments: A manual for the Learning Environment Inventory and the My Class Inventory. Halifax, NS, Canada: Atlantic Institute of Education. Bear, G. G., Gaskins, C., Blank, J., & Chen, F. F. (2011). Delaware School Climate Survey–Student: Its factor structure, concurrent validity, and reliability. Journal of School Psychology, 49, 157–174. doi:10.1016/ j.jsp.2011.01.001 Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). Contexts of child rearing: Problems and prospects. American Psychologist, 34, 844–850. doi:10.1037//0003-066X.34.10.844 Brookover, W. B., Schweitzer, J. H., Schneider, J. M., Beady, C. H., Flood, P. K., & Wisenbaker, J. M. (1978). Elementary school social climate and school achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 15, 301–318. doi:10.3102/00028312015002301 NASP | School Psychology Forum: Research in Practice Elementary Perceptions of School Climate | 63 Bryk, A. S., Sebring, P. B., Allensworth, E., Luppescu, S., & Easton, J. Q. (2010). Organizing schools for improvement: Lessons from Chicago. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Buckley, M. A., Storino, M., & Sebastiani, A. M. (2003, June). The impact of school climate: Variations by ethnicity and gender. Poster session presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association, Toronto, ON, Canada. Cohen, J., McCabe, L., Michelli, N. M., & Pickeral, T. (2009). School climate: Research, policy, practice, and teacher education. Teachers College Record, 111, 180–213. Retrieved from http://www.tcrecord.org Eccles, J. S., Wigfield, A., Midgley, C., Reuman, D., MacIver, D., & Feldlaufer, H. (1993). Negative effects of traditional middle schools on students’ motivation. Elementary School Journal, 93, 553–574. doi:10.1086/461740 Felner, R. D., Favazza, A., Shim, M., Brand, S., Gu, K., & Noonan, N. (2001). Whole school improvement and restructuring as prevention and promotion: Lessons from STEP and the project on high-performance learning communities. Journal of School Psychology, 39, 177–202. doi:10.1016/S0022-4405(01)00057-7 Furlong, M. J., Greif, J. L., Bates, M. P., Whipple, A. D., & Jimenez, T. C. (2005). Development of the California School Climate and Safety Survey—Short form. Psychology in the Schools, 42, 137–149. doi:10.1002/ pits.20053 Gottfredson, G. D., & Gottfredson, D. C. (1989). School climate, academic performance, attendance, and dropout. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 308225). Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2001). Early teacher-child relationships and the trajectory of children’s school outcomes through eighth grade. Child Development, 72, 625–638. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00301 Haynes, N. M., Comer, J. P., & Hamilton-Lee, M. (1989). School climate enhancement through parental involvement. Journal of School Psychology, 27, 87–90. doi:10.1016/0022-4405(89)90034-4 Haynes, N. M., Emmons, C., & Ben-Avie, M. (1997). School climate as a factor in student adjustment and achievement. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 8, 321–329. doi:10.1207/ s1532768xjepc0803_4 Haynes, N. M., Emmons, C. L., Ben-Avie, M., & Comer, J. P. (2001). The school development program student, staff, and parent school climate surveys. New Haven, CT: Yale Child Study Center. Hoy, W. K., Hannum, J., & Tschannen-Moran, M. (1998). Organizational climate and student achievement: A parsimonious and longitudinal view. Journal of School Leadership, 8, 336–359. Johnson, B., & Stevens, J. J. (2006). Student achievement and elementary teachers’ perceptions of school climate. Learning Environments Research, 9, 111–122. doi:10.1007/s10984-006-9007-7 Koth, C. W., Bradshaw, C. P., & Leaf, P. J. (2008). A multilevel study of predictors of student perceptions of school climate: The effect of classroom-level factors. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100, 96–104. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.100.1.96 Kuperminic, G. P., Leadbeater, B. J., Emmons, C., & Blatt, S. J. (1997). Perceived school climate and difficulties in the social adjustment of middle school students. Applied Developmental Science, 1, 76–88. doi:10.1207/s1532480xads0102_2 McNeely, C. A., Nonnemaker, J. M., & Blum, R. W. (2002). Promoting school connectedness: Evidence from the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. Journal of School Health, 72, 138–156. doi:10.1111/ j.17461561.2002.tb06533.x Merrell, K. W. (2003). Behavioral, social, and emotional assessment of children and adolescents (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Mitchell, M. M., Bradshaw, C. P., & Leaf, P. J. (2010). Student and teacher perceptions of school climate: A multilevel exploration of patterns of discrepancy. Journal of School Health, 80, 271–279. doi:10.1111/ j.1746-1561.2010.00501.x National School Climate Council. (2007). The school climate challenge: Narrowing the gap between school climate research and school climate policy, practice guidelines and teacher education policy. New York, NY: Author. Retrieved from http://www.schoolclimate.org/climate/documents/school-climatechallenge.pdf Osterman, K. F. (2000). Students’ need for belonging in the school community. Review of Educational Research, 70, 323–367. Raudenbush, S. W., & Bryk, A. S. (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. NASP | School Psychology Forum: Research in Practice Elementary Perceptions of School Climate | 64 Raudenbush, S. W., Bryk, A. S., Cheong, A. S., Fai, Y. F., Congdon, R. T., & du Toit, M. (2011). HLM 7: Hierarchical linear and nonlinear modeling. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International. Skinner, E., & Belmont, M. (1993). Motivation in the classroom: Reciprocal effects of teacher behavior and student engagement across the school year. Journal of Educational Psychology, 85, 571–581. doi:10.1037//0022-0663.85.4.571 Stamler, J. K., Scheer, D. C., & Cohen, J. (2009). Assessing school climate for school improvement: Development, validation and implications of the Student School Climate Survey (Internal report). New York, NY: Center for Social Emotional Education. Sulkowski, M. L., Bauman, S. A., Dinner, S., Nixon, C., & Davis, S. (2014). An investigation into how students respond to being victimized by peer aggression. Journal of School Violence, 13, 339–358. doi:10.1080/ 15388220.2013.857344 Thapa, A., Cohen, J., Guffey, S., & Higgins-D’Alessandro, A. (2013). A review of school climate research. Review of Educational Research, 83, 357–385. doi:10.3102/0034654313483907 Watkins, N. D., & Aber, M. S. (2009). Exploring the relationships among race class, gender, and middle school students’ perceptions of school racial climate. Equity & Excellence in Education, 42, 395–411. doi:10.1080/10665680903260218 White, N., La Salle, T. P, Ashby, J. S., & Meyers, J. (2014). A brief measure of adolescent perceptions of school climate. School Psychology Quarterly, 29, 349–359. doi:10.1037/spq0000075 Wilson, J., Pentecoste, J., & Bailey, D. (1984). The influence of sex, age, teacher experience and race on teacher perception of school climate. Education, 104, 444–445. NASP | View publication stats School Psychology Forum: Research in Practice Elementary Perceptions of School Climate | 65