2005BrownCloke NeoliberalreformgovernanceandCorruptioninCentralAmerica

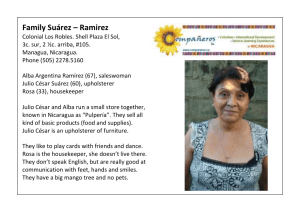

Anuncio