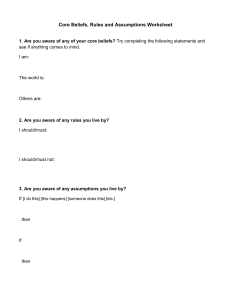

Preservice Teacher Beliefs about Teaching Thomas J. Lasley Ohio Department of Education Beliefs evolve as individuals are exposed to the ideas of their parents, peers, teachers, neighbors, and various significant others. They are acquired and fostered through schooling, through the informal observation of others, and through the folklore of a culture, and they usually persist, unmodified, unless intentionally or and mores explicitly challenged. Conflicting beliefs about teaching and the nature of teacher education have been evident since the early days of formal schooling. Teachers during the past 150 years have graduated from normal schools or teachers’ colleges as ardent advocates of a variety of educational practices. They have studied the ideas of Mann, Parker, Dewey, and Tyler and have had a variety of teaching techniques or educational philosophies taught or reinforced by faculty members during course work and student teaching. Beliefs about teaching are also fostered through literature, the media, and popular folklore. Teachers portrayed on television-The White Shadow, for example-are good looking, extremely talented, particularly in athletics, and totally dedicated to the students. Teaching is, for these television characters, an exciting, action-packed profession. They are individuals who totally enjoy working with students and find rewards through helping young people cope with the struggles of up. The implicit message of such programs is that teaching is rewarding and fulfilling. The following statements represent beliefs commonly held by teacher education candidates. The belief statements are three of many generated by this writer and others following a year-long study of first-year teachers (Ryan, Applegate, Flora, Johnston, Lasley, Mager, & Newman, 1977). They have particular significance because they represent, to a certain extent at least, the general perceptions of one group of prospective teachers as they growing entered classrooms for the first time. The statements are followed by short narratives which examine in a cursory way the veracity and implications of each belief. Beliefs about Teaching 1. Teaching is a Rewarding and Fulfilling Career Choosing a career is a complex and long-term College students switch majors many times before they finally choose a field. Even after entering the job market many people change vocations periodically during their lives. Those choosing to become teachers often disregard the status and financial problems associated process. Teaching is, for these television characters, exciting, action-packed profession. teaching and stand firmly behind a belief that teaching will be a fulfilling career. Teaching is, however, a disillusioning career for many people. They may enjoy some aspect of classroom life (e.g., interactions with students), but they become dissatisfied with education in general, citing low prestige, low pay, and petty problems associated with classroom teaching (e.g., discipline and student apathy) as important factors in their decision to seek other positions (Ryan et al., 1977; Applegate & Lasley, 1979; Walsh, 1979). Studies of teachers who have stayed in teaching for prolonged periods indicate that although periods of job satisfaction are evident during the early and middle phases of teachers’ careers, satisfaction with teaching begins to drop off again as experienced teachers move into their 50s with (Newman, 1978; Peterson, 1978). Retired teachers recall their gratifying and happy times, but they bitterness as retirement approaches. Their decline in morale at retirement may, in part at least, be attributed to problems of retiring and dealing with new roles outside the classroom. Reduced status and fewer responsibilities may also compound feelings of uncertainty and uneasiness with teaching. is consultant, Teacher Education and Certification, Ohio Department of Education, Columbus. early report careers as more Teaching is a disillusioning career for many people. They become dissatisfied with education in general. Trying to determine what makes teaching a source of satisfaction for some and dissatisfaction for others will require much more research. Why some teachers burn out while others stay turned on is not yet understood. Certainly many external factors (e.g., the types of students and parents with whom teachers work) and internal factors (e.g., teacher personality) are involved. Peterson (1978) did isolate one factor which appears significant: teachers who are periodically confronted with new challenges derive the greatest satisfaction from teaching. 2. Teacher Education Courses do Little to Prepare Teachers for the Real Classroom Teachers, particularly that Lasley an new teachers, cannot be seem to believe taught by college things simply professors (Ryan, Applegate, Flora, Johnston, Lasley, Mager, & Newman, 1979). They view their programs some 38 Downloaded from jte.sagepub.com at UNIV OF MICHIGAN on June 14, 2015 Satisfaction with teaching begins to drop off experienced teachers move into their 50s. as positively but believe that some skills are learned only through experiencing the real classroom. As one teacher in this Ryan study noted: corresponding thrust to observe classroom events for unifying instructional principles. A strong theoretical background prevents teachers from going from fad to fad, from attaching themselves to new and often spurious pedagogical notions. The student of the practical, as Dewey (1904) noted, Adjusts methods of teaching, not to the principles which he is acquiring but to what he sees succeed and fail in an empirical way from moment to moment: to what he sees other teachers doing who are more experienced and successful in keeping order than he is; and to injunctions and directions given him by others. program was good, but so much was needed that can’t be put into a course or a textbook. It was just being out there and doing. I My teacher training felt as prepared as I could ever be. (p. 269). Newman (1979) reports that experienced teachers also view their teacher education programs positively, and, like their neophyte counterparts, believe that some things cannot be learned until one has responsibility for students. Teachers in both the Ryan and Newman studies cited responsibility for students and taking charge of a real class as critical to professional growth; they were considered essential prerequisites to understanding what it meant to be a teacher. Their subjects said this understanding could not be acquired vicariously through field-experience observations; it had to be experienced first-hand through direct teaching. The increased number of field experiences in some teacher education programs is undoubtedly a response to the concern for less abstraction and less second-hand experience in teacher preparation programs. Increased emphasis on the practical and expanded time in real classrooms should not, however, overshadow the need for the theoretical. Theory provides a framework for understanding practice. Preservice students who spend hundreds of hours in schools without attempting to learn basic principles to explain what they are observing gain very little from their efforts. Increased field experiences and emphasis on the practical are pointless without a Preservice teachers often cite their love of children important predictor of their classroom that effective teaching will result if one as an They assume likes being around success. (p. 14) 3. People who Like Children are Effective Teachers Preservice teachers often cite their love of children as important predictor of their classroom success. They assume that if one likes children and enjoys being around an them, effective teaching will result. Teacher effectiveness research has not clearly detailed what ensures effective teaching, but it does indicate that simply liking children is not enough. The preservice teacher who believes that good teaching is the result of simply enjoying children assumes that teaching is primarily an art. In actuality, teaching seems to be a combination of art and science (Gage, 1978). The artistry of teaching is that aspect which is nonquantifiable. It is reflected in the first-grade teacher who, despite unorthodox methods and unusual techniques, consistently enables all the students to read. It is reflected Teachers who are periodically confronted with challenges derive the greatest satisfaction from teaching. new children. Teacher effectiveness research indicates that simply liking children is not enough. Photo courtesy of Northern Illinois University Art/Photo Office by Barry Stark. 39 Downloaded from jte.sagepub.com at UNIV OF MICHIGAN on June 14, 2015 Increased emphasis on the practical should not overshadow the need for the theoretical. junior high school mathematics teacher who fosters within students a love for mathematics, has students excitedly measuring objects all over the school building, in the seldom follows the exact plans suggested by the teachers’ edition of the textbook, but consistently produces good math students. The art of teaching requires intuition and insight, the integration of many elements into a whole. It requires utilizing and combining known elements in the realm of the unknown. Teaching as a science, on the other hand, implies that laws exist which can be used to predict outcomes and that certain teacher behaviors will cause certain student responses. The research on teacher effectiveness is an effort to identify concepts which will help teachers provide effective instruction. The teacher effectiveness research is gratifying, but such research will probably not end the debate on whether teaching is partially art. Learning about the science of teaching usually occurs during professional education course work. Developing the art of teaching begins the first time a preservice teacher tries to use a set of principles about learning to accomplish a specific objective in the classroom. Someone who likes children but can neither identify basic instructional principles nor weave those principles together to form a coherent lesson will have difficulty accomplishing learning goals. Challenging Beliefs Brain that &dquo;belief systems not worth having&dquo; (p. 289). Preservice teacher have many beliefs similar to those noted above, beliefs which are unsubstantiated yet often persist throughout their teacher education programs. Are teacher educators doing everything they can to encourage prospective teachers to critically examine their beliefs about teaching? Are they striving to foster attitudes which more closely approximate educational realities? In his 95 Theses, Martin Luther stated his beliefs about God and Rome; then he detailed reasons for those beliefs. Something similar is needed in the world of preservice teacher education. Perhaps teacher education students should be required to develop and defend a set of belief statements about the nature of teachers, teacher education, and the classroom. The statements would represent their educational beliefs and would be developed as part of the professional education course work, ideally during courses with heavy field-based components. The field experiences would enable students to generate data from their own observations and experience as well as from relevant and related research. An exercise for examining beliefs might be structured as follows. First, students should be asked to generate wrote in Broca’s cannot survive scrutiny are Sagan (1979) that that if one likes effective teaching will result. Preservice teachers children, probably assume belief statements practice, statements on a particular educational concept, (e.g., effective teaching). The should be clear and concise descriptions of or process they believe. Secondly, students should be required to provide evidence, if possible, for and against each proposed belief statement. For example, if a student asserts that effective teachers are warm and caring people who like children, that student should attempt to produce evidence for and against the statement. Searching for both types of evidence is extremely important: providing only supportive evidence would do little to challenge extant beliefs; providing only refuting evidence, on the other hand, may inaccurately represent a particular belief statement as totally false. Given the complexity of education phenomena, it is doubtful whether beliefs about teaching would be true or false in an absolute sense. Students would probably find-as do most educational researchers-that some belief statements (or hypotheses) have very little empirical support while others have extremely strong support. what The art of teaching requires intuition and insight, the integration of many elements into a whole. Finally, based on the relevant evidence (research reported in professional journals, interviews with classroom teachers, or their own classroom observations), the students should be asked to write a narrative for each which they cite supporting and refuting evidence. Once the available evidence is stated, they should label each of their belief statements (e.g., strongly supportable, somewhat supportable). In essence, to what degree do they have confidence in their belief statements? An excellent book for preservice students to read as they grapple with their own beliefs is Combs’ (1979) Myths in Education. Combs’ aproach in analyzing such notions as &dquo;The Myth of Our Competitive Society&dquo; and &dquo;The Myth of Fixed Intelligence&dquo; may help students as they begin to explore their own convictions. Though Combs’ definition of a myth is quite narrow, his effort to examine the nature of prevalent myths is valuable. statement in Perhaps teacher education students should be required to develop and defend a set of belief statements about the nature of teachers, teacher education, and the classroom. Classroom practice should not be the unquestioning of conventional wisdom, particularly conventional wisdom which may be based on folklore or uncritical observation. Teachers who teach the way they were taught, whose beliefs about teaching remain unchanged throughout a teacher education program, naturally question the value of professional education courses. Further, their beliefs, if unchallenged, have the potential for engendering frustration and creating disenchantment use 40 Downloaded from jte.sagepub.com at UNIV OF MICHIGAN on June 14, 2015 Unchallenged beliefs can engender frustration when student teachers expect a reality that does not exist. Combs, A. Myths in education. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1979. Dewey, J. The relation of theory to practice in education. In C.A. McMurry (Ed.), The third yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education. Bloomington, III.: Public School Publishing, 1904. N. The scientific basis for the art of teaching. New York: Teachers College Press, 1978. Newman, K. Middle-aged experience teachers’ perceptions of their career development. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, The Ohio State University, 1978. Peterson, A. Career patterns of secondary school teachers: An exploratory interview study of retired teachers. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, The Ohio State Gage, when student teachers enter the classroom expecting a reality that does not exist. Unchallenged beliefs may even hinder learning about more appropriate responses to the reality that does exist. Luther presented his 95 Theses on what is now celebrated as Halloween Day. His convictions, like the goblins and ghosts so closely associated with Halloween, were unsettling to many who read his statements of faith. Would preservice teachers be unsettled by what they found if they were challenged to provide support for their beliefs about education and the classroom? Would they find that their beliefs were, like ghosts and goblins, illusory? Classroom practice should not be the unquestioning use of conventional wisdom. References Applegate, J., & Lasley, T. The second-year teacher study. Paper presented at the American Educational Research Association meeting, San Francisco, April 1979. University, 1978. Ryan, K., Applegate, J., Johnston, J., Lasley, T., Mager, G., & Newman, K. The first-year teacher study. Paper presented at the American Educational Research Association meeting, New York, 1977. Ryan, K., Applegate, J., Flora, R., Johnston, J., Lasley, T., Mager, G., & Newman, K. "My teacher education program? Well..." First-year teachers reflect and react. Peabody Journal of education, March 1979, 56, 267-271. Sagan, C. Broca’s brain. New York: Random House, 1979. Walsh, K Classroom stress and teacher burnout. Phi Delta , 253-254. 61 Kappan, January 1979, Are teacher educators doing everything they can to encourage prospective teachers to critically examine their beliefs about teaching? 41 Downloaded from jte.sagepub.com at UNIV OF MICHIGAN on June 14, 2015