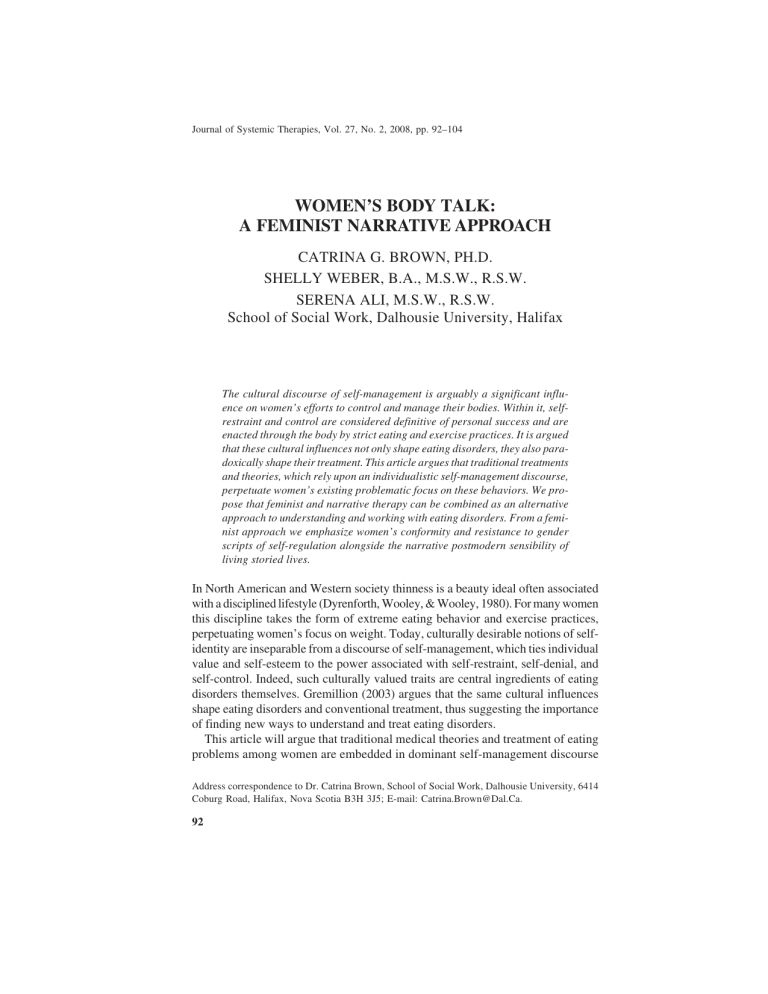

92 Journal of Systemic Therapies, Vol. 27, No. 2, 2008, pp. 92–104 Brown et al. WOMEN’S BODY TALK: A FEMINIST NARRATIVE APPROACH CATRINA G. BROWN, PH.D. SHELLY WEBER, B.A., M.S.W., R.S.W. SERENA ALI, M.S.W., R.S.W. School of Social Work, Dalhousie University, Halifax The cultural discourse of self-management is arguably a significant influence on women’s efforts to control and manage their bodies. Within it, selfrestraint and control are considered definitive of personal success and are enacted through the body by strict eating and exercise practices. It is argued that these cultural influences not only shape eating disorders, they also paradoxically shape their treatment. This article argues that traditional treatments and theories, which rely upon an individualistic self-management discourse, perpetuate women’s existing problematic focus on these behaviors. We propose that feminist and narrative therapy can be combined as an alternative approach to understanding and working with eating disorders. From a feminist approach we emphasize women’s conformity and resistance to gender scripts of self-regulation alongside the narrative postmodern sensibility of living storied lives. In North American and Western society thinness is a beauty ideal often associated with a disciplined lifestyle (Dyrenforth, Wooley, & Wooley, 1980). For many women this discipline takes the form of extreme eating behavior and exercise practices, perpetuating women’s focus on weight. Today, culturally desirable notions of selfidentity are inseparable from a discourse of self-management, which ties individual value and self-esteem to the power associated with self-restraint, self-denial, and self-control. Indeed, such culturally valued traits are central ingredients of eating disorders themselves. Gremillion (2003) argues that the same cultural influences shape eating disorders and conventional treatment, thus suggesting the importance of finding new ways to understand and treat eating disorders. This article will argue that traditional medical theories and treatment of eating problems among women are embedded in dominant self-management discourse Address correspondence to Dr. Catrina Brown, School of Social Work, Dalhousie University, 6414 Coburg Road, Halifax, Nova Scotia B3H 3J5; E-mail: Catrina.Brown@Dal.Ca. 92 Women and Body Talk 93 and that their focus on body weight management and food intake perpetuate women’s existing problematic focus on weight and eating. We propose that feminist and narrative therapy can be combined to offer an alternative approach to understanding and working with the continuum of eating problems women experience. It will be argued that this alternative approach shifts the focus from preoccupation with the body to exploration of the meaning of women’s struggles with their bodies and assists in the creation of new stories of identity which are not dependent on self-restraint, denial, and control. We begin by offering our framework for contextualizing eating disorders, which serves as a lens for our critique of medical treatment. We then outline a treatment model for eating disorders that blends feminist and narrative therapy and conclude with a clinical case to illustrate this blended approach. CONTEXTUALIZING EATING DISORDERS Current understandings of the role of social factors in the development of weight preoccupation and eating disorders are often “[s]hallow and unsystematic” and their primary focus on aesthetics denotes women as products of culture, rather than active agents (Bordo, 1993, p. 45). Missing have been personal accounts (see Hosking, 2001) and explorations of the imperative of the thin body ideal as a culturally and historically formed phenomenon that tells a story about women in culture. Drawing on Foucault (1995), eating disorders are historically and culturally specific: they “emit signs.” Women who struggle with eating disorders are but “[t]he bearers of very distressing tidings about our culture” (Bordo, 1993, p. 60). When we recognize the ways in which the body is in the grip of culture, women’s struggles with their bodies make sense (Foucault, 1980). Feminists such as Bordo (1993), Brown and Jasper (1993), Lawrence (1979), and Orbach (1986) believe that women control their bodies as a way in which to achieve a sense of agency in their lives. Gremillion (2003) and Brown (2007a) suggest that feminist therapy needs to address how women’s struggles with their bodies are both cultural forms of compliance and resistance. Gremillion writes that women who struggle with eating disorders “[a]ppropriate powerful social norms about feminine autonomy and self-control and challenge these norms by enacting them through eating disorder behaviours” (2003, pp. 194–195). Women’s communication through their bodies or “body talk” reveals hidden struggles about who they believe they should be as “women” within society. Femininity is shaped by the prevailing discourse of self-management and the gendered expectation of self-restraint is played out through women’s dieting and weight control. Further, women struggle with the contradictory social messages of a bulimic culture (Bordo, 1993). One message dictates the imperatives of consumer culture—to consume endlessly, to capitulate to temptation, and desire—and another, the imperative of self-management which demands the restriction of 94 Brown et al. excess, temptation, or desire. These contradictory messages of excess and restraint associate slenderness with control, power, and success and fatness with loss of control and personal inadequacy (Bordo, 1993; Brown, 2005). Gremillion’s (2003) research demonstrates that not only are women with eating disorders recruited into culturally based self-management practices of continual evaluations and comparisons, strict self-surveillance, and denial of personal desires, but that these same patterns are reproduced within treatment itself. Treatment that focuses on behavioral strategies serves to reinforce the logic behind eating disorders. Within this logic the body is an object that needs to be resourced to create a certain kind of self (Gremillion, 2003). Typically, medically based treatment programs involve a highly structured environment that focuses primarily on monitoring and managing women’s behavior. This creates a situation in which individuals develop strategies to avoid eating or weight gain in an attempt to gain back some control (Gremillion, 2003). In response to these behaviors, medical treatment programs have created their own strategies for individuals viewed as “noncompliant.” While these medical practices are meant to be deterrents to eating disorder behavior, they fail to acknowledge and undermine the way women resource their bodies to maintain a sense of autonomy and self-control (Gremillion, 2003). In turn this may inadvertently exacerbate women’s anxieties and perceived lack of control over their lives and intensify their subsequent efforts to achieve control through the body. FORMULATING AN ALTERNATIVE APPROACH An alternative treatment approach blends feminist and narrative therapy, drawing on both modern and postmodern theory. It recognizes that women’s experiences of the body, expressed as eating disorders, reflect gender socialization and the cultural practices and discourses of self-management. Within this blended approach the therapist is politically positioned, working collaboratively with women to challenge dominant social narratives and help reconceptualize how women resource or use their bodies. Women’s use of their bodies or “body talk” is a form of expression that both resists and reflects culture (Brown, 2007b). From this perspective, eating disorders and weight preoccupation are not contextualized simply as individual problems located within the person, but rather as a distinct reflection of contradictory social and cultural discourses. Feminist Therapy Feminist therapy developed as a critique to traditional androcentric forms of intervention, which individualized and pathologized women’s experiences, and as a challenge to falsely universalized and privileged male norms. Feminist ap- Women and Body Talk 95 proaches have recognized eating problems as gendered and emphasized a nonpathologizing and socially contextualized approach to understanding and treating the continuum of weight preoccupation and eating disorders among women (Bloom et al, 1994; Brown, L., 1989; Brown & Forgay, 1987; Chernin, 1981; Dyrenforth, Wooley, & Wooley, 1980; Fallon, Katzman, & Wooley, 1994; Lawrence, 1984, 1987; Lawrence & Dana, 1990; Orbach, 1978, 1986; Root & Fallon, 1989; Wooley & Wooley, 1986a, 1986b). Medical approaches perpetuate the doctor as expert and the power differentials between doctors and patients, producing struggles over issues of bodily control (Brown, 1993a; Gremillion, 2003; Lawrence, 1984). In contrast, feminist approaches to working with eating disorders and weight preoccupation emphasize empowerment, social change, and self-direction. They also recognize that the problem itself is an extension of the experiences many women have with their bodies and eating. The goal of feminist intervention is to work collaboratively with women struggling within the continuum of eating problems, not only to understand the meaning of these struggles, but to develop alternative ways of communicating them and to create preferred stories that challenge the dominant self-management discourse. Feminist therapists have identified that a “control paradox” is often central to eating disorders and weight preoccupation (Brown, 1993a, 1993b; Lawrence, 1979, 1984). While a woman with an eating disorder may feel out of control, her efforts at self-regulation and controlling her eating and body weight often offer her a strong sense of mastery (Brown, 1993a). The thought of giving up the power achieved through self-restraint is often terrifying. Feminist therapy seeks to establish a therapeutic alliance that fosters an important sense of power, control, and emotional safety for women. This approach recognizes the positive intentions and effects associated with controlling and regulating the body. Feminist therapy acknowledges that therapy is not neutral, thus the therapist must ensure she is aware of and accountable for her use of power in the therapeutic relationship. Therapeutic methods such as feminist contracting offer a collaborative process in which the goals, expectations, and pace of therapy are negotiated between therapist and client (Brown, 1993b). Through feminist contracting client empowerment and self-determination are emphasized and a safe therapeutic environment is established (Brown, 1993b). An example of feminist contracting is a negotiation between the therapist and client about a minimum weight and health status, allowing for the therapeutic work to proceed without over-focusing on physical symptoms (see Brown, 1993a). Importantly, feminist contracting honors the positive intentions and effects associated with anorexia and bulimia while also reducing the harm associated with negative effects. Further, shifting the focus of intervention away from weight preoccupation and eating behavior leaves room to explore how these preoccupations distract women from the meaning of their struggles. 96 Brown et al. Narrative Therapy Central to narrative therapy is the belief that we live storied lives and that people organize and assign meaning to their lived experiences through stories about them (White & Epston, 1990). Narrative therapy assumes that the meaning ascribed to stories will change, depending on the context. It also presupposes a person’s life is multi-storied, that no story is free of uncertainty or contradictions, and that stories often disguise dynamics of power and control (White, 1991). In narrative therapy, clients and therapists work collaboratively to deconstruct old narratives and coauthor new narratives, recognizing that each bring their own knowledge to the process (Brown, 2003). An understanding of the problem is achieved by focusing on language, power relations, and the ways in which people interpret and assign meaning to their experiences (White, 1991). According to White (1991) stories are never neutral, thus they need to be told, deconstructed, and reconstructed. The unpacking of people’s experiences involves exploring how aspects of stories have been disqualified or rendered invisible (White & Epston, 1990). The act of resurrecting subjugated knowledge disrupts the idea that there is one objective truth universal to all people and reveals the “political” or non-neutral nature of the ideas (Brown, 2003). This process can help challenge the dominant discourse that people internalize as truth in their stories about themselves. A central technique of narrative therapy is the process of “externalization.” The aim of externalizing is to separate the individual from the problem and to create alternative stories that include subjugated knowledge and unique outcomes which, in turn, facilitate the construction and performance of new stories (White & Epston, 1990). Unique outcomes “[i]llustrate that other stories exist, that dominant discourse does not always prevail, and offers rich alternatives that can begin to form reconstructed stories” (Brown, 2003, p. 236). As alternative narratives emerge, clients can separate themselves from their unhelpful dominant stories and experience agency and a capacity to “[i]ntervene in their own lives and relationships” (White & Epston, 1990, p. 16). In externalizing eating disorders, narrative therapy acknowledges the social pressure to be thin (Grieves, 1998; Kraner & Ingram, 1998; Madigan & Goldner, 1998; Maisel, Epston, & Borden, 2004; Nylund, 2002). Narrative therapy conceptualizes eating disorders as the highest level of achievement or mastery in the processes of self-regulation (Gremillion, 2003). However, within this narrative process some regard women primarily as victims of social pressures to be thin and the subsequent therapeutic intervention focuses on assisting women to claim their power by “fighting back” against the enemy of the eating disorder (Brown, 2005, 2007b). There may be a number of significant risks associated with totalizing eating disorders as negative (White, 2007). According to White (2007) “totalizing can obscure the broader context of the problems that people bring to therapy and can invalidate what people give value to and what might be sustaining” Women and Body Talk 97 (p. 35). When the focus of externalization is on creating an “anti-anorexic” or “antibulimic” stance, the important content of women’s struggle and their efforts to talk through the body is rendered invisible. If women are positioned solely as victims or products of culture therapy may negate the agency and resistance women often express through their bodies (Brown, 2007b). Consequently, the process of externalizing within narrative therapy may create and reinforce a dichotomy between the individual and the problem, in which the problem is portrayed as entirely pathological and the individual as helpless victim or courageous resistor (Gremillion, 2003; White, 2007). Merging Feminist and Narrative Therapies Through a blended approach, therapists attempt to understand women’s body talk without pathologizing their experiences (Brown, 2005). Both feminist and narrative approaches acknowledge that therapy is an interpretive process. By focusing on the cultural context which shapes women’s experiences of their bodies, feminist therapy avoids reinforcing “[t]he existing displacement of a client’s emotional struggles onto the body and obscuring the larger and more substantial issues” (Brown, 1993a, p. 192). Furthermore, feminist therapy emphasizes the need to explore the multiple meanings of eating problems and weight preoccupation for the women experiencing them, including their positive intent and effects, and potential negative effects. Similarly, narrative therapy offers a nonblaming stance by discussing experiences with eating disorders in a manner that separates it from women’s identities (Gremillion, 2003). Such a separation is vital, as most women enter therapy with the message that they “are” anorexic or bulimic. As the eating disorder experiences are externalized and located within their cultural context, “[t]he ongoing cultural work involved in the construction of illness becomes visible” (Gremillion, 2003, p. 195). A narrative approach helps women begin to understand how discourses in the wider social context support the problem description they have of themselves and aims to help externalize the problem from the person. This is consistent with feminism’s efforts at empowerment through consciousness raising and contextualizing women’s experiences (Worell & Remer, 1992). A combined feminist and narrative approach may help acknowledge the critical role of women’s agency in their lived experiences and may be useful in moving away from therapeutic constructions of women as passive victims of either eating disorders or culture (Brown, 2005). The therapeutic goal of this process is to help women explore the meaning of their body talk and the ways that it may communicate both conformance and resistance to gendered subjectivities (Brown, 2005). Feminist therapy brings to narrative therapy an emphasis on women’s agency within therapeutic processes of contextualizing gendered stories. Conversely, narrative therapy offers feminist therapy a way to move past the deconstruction of problem stories through the idea of reconstructing or rewriting alternative more helpful stories of identity. Therapy 98 Brown et al. needs to take into account that life context and experience shape individual’s particular engagement with the dominant discourse of self-management and how individual stories of self-regulating through the body are played out. SHAYNA Shayna is a 23 year old Jewish Canadian woman who is episodically bulimic, as well as a restrictive eater with a low but stable body weight of 90 pounds. She shares that she began to focus on her weight at age 16 and describes often feeling out of control. While she has begun to go out socially on occasion, she is generally quite isolated. When we began to work together Shayna often said “I don’t know” when asked a question. Shayna is currently completing a theater degree at university and has received feedback in her program that she needs to learn to “let go” or express herself more. Shayna reports feeling stressed out and anxious about her studies as she never feels good enough. The more stressed out and anxious Shayna feels the more self-critical she is and it is at these times that she is very likely to binge and purge. Following periods of bingeing and purging she returns to very restrictive eating. Shayna exercises daily and observes that she feels more in control, confident, and better about herself when she does. Weekly individual therapy sessions continued for about 18 months. By the end of these sessions Shayna had a greater understanding of the meanings she associated with bingeing and purging and her desire to be thin. This understanding led her to challenge the dominant discourse which ties self-regulation to a sense of control and self-worth. She no longer said “I don’t know” when asked a question and risked being more expressive. She continued to maintain a stable low body weight and was able to limit her bingeing and purging to periods of heightened stress. EXTERNALIZING STORIES OF CONTROL Our feminist narrative approach to externalizing Shayna’s story focuses on three areas of exploration. First, we begin the process of externalization by honoring and exploring the positive intentions behind Shayna’s eating problems. The second aspect of externalization emphasizes the complexity and contradictions in her story. This involves exploring both the positive and negative effects of the anorexia and bulimia. The third focus of externalization we discuss is centered on creating alternative stories which support alternative ways of managing positive intentions. Initially, a blend of feminist and narrative therapy will shift the focus away from dominant social discourses which pathologize eating disorders and focus on managing behavior. Instead the conversation will shift toward understanding the control paradox and the meanings associated with eating problems for Shayna. Unpacking Women and Body Talk 99 Shayna’s dominant story of control involves challenging the social story of selfmanagement and appreciating the meaning that controlling her body and eating has come to have for her. The creation of an alternative story for Shayna necessarily involves both unpacking the dominant social story that being in control “is good” and being out of control “is bad” and differentiating between harmful and helpful practices of self-management. This approach challenges the story that she is only good enough when she is thin enough or when she has attained a sense of control over her body. At the same time, it does not minimize the real sense of power that Shayna gets from controlling her body and eating. Through a gradual and in-depth exploration of less restrictive, oppressive, and extreme methods of attaining a sense of control over herself and her body Shayna can begin to develop an alternative identity story that moves beyond the limitations of the dominant self-management discourse and practices. Questions around the theme of unpacking self-management and self-control explore what feeling out of control is like for Shayna, how it is not tolerated, and how it is displaced onto controlling her body. While these questions provide a kind of scaffold for therapeutic conversations, one would probe and explore the meaning around each of these questions for Shayna in greater depth. Therapists can begin this process by offering comments which invite women to move past a focus on weight, eating, and control: “Sometimes when women struggle with eating problems they talk about them as a way to cope. We can work together to try to understand what they mean to you. In order to do this we will shift away from only focusing on weight and eating.” These questions invite Shayna to explore a richer story of her eating problems: • • If anorexia or bulimia tell a story about you, what do you think they are saying? What does anorexia or bulimia say about you that most people might be surprised to know? The following questions continue to shift Shayna’s focus away from a preoccupation with controlling weight and eating to the idea that this focus often distracts her from alternative levels of meaning. These externalizing questions address the first task of externalizing we are focusing on by exploring and honoring the positive intentions of Shayna’s struggles with eating and weight. Initially it is helpful to recognize the positive intentions associated with her desire to feel more in control. • • • • • Are there times when you are most likely to want to binge eat? Do you feel more or less in control when you binge eat? Do you feel more or less in control when you control your eating? What are other ways or times you feel in control of yourself? What things make you feel anxious or out of control in your life? 100 Brown et al. • • Are you more or less likely to binge eat at these times? Purge? Exercise? Does purging make you feel more in control? (If so), how does it do this? A second task of externalizing is to move beyond positive intentions. The second task highlighted here explores how Shayna makes sense of anorexia and bulimia as resources to feel more in control and less anxious, as well as the ways that they are not helpful to her. These kinds of questions hold onto the idea that Shayna is her own agent and that while aspects of anorexia and bulimia are not helpful to her, there are many aspects that are indeed meaningful in that they help her cope with uncertainty, anxiety, and not feeling good enough. Simultaneously, we can begin to acknowledge the importance of her finding alternative ways of attaining a great sense of power and control in her life and of expressing disqualified stories. • • • • • • • • • Do you feel bingeing and purging, exercising and restrictive eating are useful to you? What are the positive effects of these behaviors? How are they helpful to you? What are the negative effects of these behaviors? How are they not helpful to you? What part of you would prefer to use anorexia and bulimia? What part of you would prefer to not use anorexia and bulimia? What do you think about the positive and negative effects of anorexia and bulimia on your life? What do these effects say to you about your struggle with anorexia and bulimia? If you were to imagine giving up anorexia or bulimia right now what would you feel you are giving up? Tell me about what would be hard about it for you. A third role of externalizing is the creation of less oppressive, alternative stories that encourage Shayna to express herself more directly, rather than through her body. These new stories can help create other ways of managing positive intentions. Within a feminist narrative process, it is important to explore the history of how she has participated in her control story and what aspects of her life fall outside this story. For women, the dominant gender scripts of what it means to be a “good girl” become intertwined with and reinforce the importance of self-management. Femininity involves a particular performance of “being nice” that too often involves suppressing or disqualifying aspects of experience in order to not offend or upset anyone else. Interestingly, despite the fact that parents, doctors, and therapists usually want women to give up their eating disorders, women typically refuse to comply, often maintaining, like Shayna that it is the only thing that is just for her. Although perhaps controversial, we suggest that during this externalization process it is important to explore how controlling the body conforms to self-management Women and Body Talk 101 practices and how it is itself a unique outcome. Totalizing the negative aspects of eating disorders does not permit us to see potential unique outcomes. We have argued that it is important to look at the positive intent and both the positive and negative effects of eating disorders. Clinically, women report that there are short term positive effects including feeling more in control, more powerful, an increase in self-worth, and emotional release or tension reduction. While it is important to give voice to these experiences it is also important to explore the negative and longer term effects on women’s lives. Shayna’s resistance is a unique outcome because she rarely takes a stance that opposed others’ wishes or that was unequivocally about what she feels she wants or needs. While conforming to the demand for self-management and a restrained voice, anorexia and bulimia, paradoxically provide a self-managed and contained expression of struggle and resistance. For Shayna, her struggle with voice is evident in her theater studies, in her anorexic and bulimic body talk, and in her “I don’t know” stance in therapy. This conversation might begin when Shayna says “I don’t know” in a session. • • • • • • • • When you say you “don’t know” is it hard for you to say what you are feeling or thinking? Are there times when you feel you are able to “let go” or express yourself? What is that like for you? What is different about these times? How do people react to you at these times? What happens to your voice when you don’t express it? Do you think anorexia and bulimia might be a way for you to express yourself? How do you feel when others ask you to give up your eating disorders? The exploration of unique outcomes provides an entry point for developing an alternative more helpful story by asking how the eating disorders do not fit within scripts of self-management; and in fact, resist them. This means exploring how eating disorders may express aspects of Shayna’s experiences which have been disqualified and subsequently, her ambivalence to abandon them. By doing so Shayna can become more aware of how unspoken and uncertain aspects of her experiences have been rendered invisible and she can choose what she wishes to resurrect. Feminist narrative therapy will support Shayna to express those aspects of her experience previously disqualified. Subjugated aspects of her dominant story of control are examined in such a way that she can deliberately choose what works best for her. This approach allows us to explore the “both/and”: the ways that eating problems are restrictive and self-disciplining and the ways that they are expressive and quietly resist self-restraint. A feminist narrative approach would also involve exploring with Shayna how she may have come to value the idea of self-restraint and self-control at the same time that she actually finds it difficult to express herself within her theater studies, 102 Brown et al. her relationships, and in therapy itself. Through externalizing the language “I don’t know” alongside the idea of having difficulty “letting go” or expressing herself, feminist narrative therapy can unpack the limitation of self-management discourse on her voice and begin to explore how the body seems to be telling a story. By focusing questions directly on the meaning that Shayna attaches to anorexic and bulimic behaviors we can begin to explore how they are tied to cultural and personal beliefs about being in control, as well as how they contain and express disqualified stories. Through these three pathways of externalizing Shayna’s story we help make sense of the story and in doing so, provide an entry point to explore alternative stories for her that might ultimately be more helpful. CONCLUSION Mainstream medical discourses have served to reinforce cultural ideals of selfmanagement by focusing on fitness and weight preoccupation to control the body and by representing women with eating disorders as being out of, and in need of, control (Gremillion, 2003). Feminist and narrative therapies critique the dominant medical discourses, arguing they have contributed to the maintenance of gender inequalities and the pathologizing of the female body (Malson, 1997). By integrating feminist and narrative therapies, eating disorders and weight preoccupation are reconceptualized from traditional discourses that cast them as individual psychopathologies into socially and historically specific conditions (Brown, 2007b). Additionally, combined feminist and narrative therapies can assist in externalizing experiences with eating disorders without removing a woman’s agency in the process. Women can then make sense of their struggles with their bodies, challenge the constraining effects of self-management discourse, and create alternative identity stories. While we have addressed aspects of gendered selfregulation, this approach to externalizing experiences among women with eating disorders may be used when working with other specific populations by addressing the specific elements of their stories constructed within the dominant cultural discourse of self-management. REFERENCES Bloom, C., Gitter, A., Gutwill, S., Kogel, L., & Zaphiropoulos, L. (1994). Eating problems. A feminist psychoanalytic treatment model. New York: Basic Books. Bordo, S. (1993). Unbearable weight: Feminism, western culture, and the body. Berkeley: University of California Press. Brown, C. (1993a). Feminist therapy: Power, ethics, and control. In C. Brown & K. Jasper (Eds.), Consuming passions: Feminist approaches to weight preoccupation and eating disorders (pp. 120–136). Toronto: Second Story Press. Women and Body Talk 103 Brown, C. (1993b). Feminist contracting: Power and empowerment in therapy. In C. Brown & K. Jasper (Eds.), Consuming passions: Feminist approaches to weight preoccupation and eating disorders (pp. 176–194). Toronto: Second Story Press. Brown, C. (2003). Narrative therapy: Reifying or challenging dominant discourse. In W. Shera (Ed.), Emerging perspectives on anti-oppressive practice (pp. 223–245). Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press. Brown, C. (2005). Body talk conversations: Uncovering the yet to be spoken. In S. Cooper & J. Duvall (Eds.), Catching the winds of change (pp. 64–75). Toronto: Brief Therapy Network. Brown, C. (2007a). Discipline and desire: Regulating the body/self. In C. Brown & T. Augusta-Scott (Eds.), Narrative therapy. Making meaning, making lives (pp. 105– 132). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Brown, C. (2007b). Talking body talk: Merging feminist and narrative approaches to practice. In C. Brown & T. Augusta-Scott (Eds.), Narrative therapy. Making meaning, making lives (pp. 269–302). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Brown, C., & Forgay, D. (1987). An uncertain well-being: Weight control and self control. Healthsharing, Winter, 11–15. Brown, L. (1989). Fat-oppressive attitudes and the feminist therapist: Directions for change. Women and therapy, 8(3), 19–29. Chernin, K. (1981). The obsession: Reflections of the tyranny of slenderness. New York: Harper and Row. Dyrenforth, S., Wooley. O., & Wooley, S. (1980). A woman’s body in a man’s world: A review of findings on body image and weight control. In R. Kaplan (Ed.), A woman’s conflict. The special relationship between women and food (pp. 30–57). New Jersey: Prentice Hall. Fallon, P., Katzman, M., & Wooley, S. (1994). Feminist perspectives on eating disorders. New York: Guilford. Foucault, M. (1980). The history of sexuality. Volume 1. An introduction. New York: Vintage. Foucault, M. (1995). (Second Edition). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. New York: Vintage. Gremillion, H. (2003). Feeding anorexia: Gender and power at a treatment center. Durham: Duke University Press. Grieves, L. (1998). From beginning to start. The Vancouver Anti-Anorexia/Anti-Bulimia League. In S. Madigan & I. Law (Eds.), Praxis. Situating discourse, feminism and politics in narrative therapies (pp. 197–205). Vancouver: Cardigan Press. Hosking, C. (2001). My body will not be excluded. In Dulwich Centre Publications Working with stories of women’s lives (pp. 159–164). Adelaide, Australia: Dulwich Centre Publications. Kraner, M., & Ingram, K. (1998). Busting out—Busting free. A group program for young women wanting to reclaim their lives from anorexia nervosa. In C. White & D. Denborough, Introducing narrative therapy: A collection of practice-based writings (pp. 91–115). Adelaide: Dulwich Centre Publications. Lawrence, M. (1979). Anorexia nervosa—The control paradox. Women’s Studies International, 2, 93–101. Lawrence, M. (1984). The anorexic experience. London: The Women’s Press. Lawrence, M. (Ed.). (1987). Fed up and hungry: Women, oppression, and food. London: The Women’s Press. 104 Brown et al. Lawrence, M., & Dana, M. (1990). Fighting food: Coping with eating disorders. London: Penguin Books. Madigan, S., & Goldner, E. (1998). A narrative approach to anorexia: Discourse, reflexivity, and questions. In M. Hoyt (Ed.), The handbook of constructive therapies (pp. 380–399). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Maisel, R., Epston, D., & Borden, A. (2004). Biting the hand that starves you: Inspiring resistance to anorexia and bulimia. New York: Norton. Nyland, D. (2002). Poetic means to anti-anorexic ends. Journal of systemic therapies, 21(4), 18–34. Orbach, S. (1978). Fat is a feminist issue. New York: Paddington Books. Orbach, S. (1986). Hunger strike: The anorectic struggle as a metaphor for our age. New York: Norton. Root, M., & Fallon, P. (1989). Treating the victimized bulimic. The functions of bingepurge. Journal of international violence 4(1), March, 90–100. White, M. (1991). Deconstruction and therapy. Dulwich Centre Newsletter, 2, 21–40. White, M. (2007). Maps of narrative practice. New York: Norton. White, M., & Epston, D. (1990). Narrative means to therapeutic ends. New York: Norton. Wooley, S., & Wooley, O. (1986a). Editorial: The Beverly Hills eating disorder: The mass marketing of anorexia nervosa. International journal of eating disorders, 1(3), 57–69. Wooley, S., & Wooley, O. (1986b). Ambitious bulimics: Thinness mania. American health, October, 68–74. Worell, J., & Remer, P. (1992). Feminist perspectives in therapy. An empowerment model. New York: Wiley.