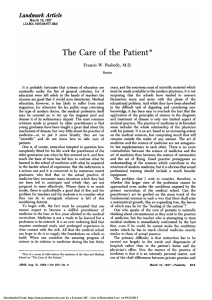

International Journal of Obesity (2013) 37, 1415–1421 & 2013 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0307-0565/13 www.nature.com/ijo ORIGINAL ARTICLE The effect of physicians’ body weight on patient attitudes: implications for physician selection, trust and adherence to medical advice RM Puhl, JA Gold, J Luedicke and JA DePierre BACKGROUND: Research has documented negative stigma by health providers toward overweight and obese patients, but it is unknown whether physicians themselves are vulnerable to weight bias from patients. PURPOSE: This study assessed public perceptions of normal weight, overweight or obese physicians to identify how physicians’ body weight affects patients’ selection, trust and willingness to follow the medical advice of providers. METHODS: An online sample of 358 adults were randomly assigned to one of three survey conditions in which they completed a questionnaire assessing their perceptions of physicians who were described as normal weight, overweight or obese. Participants also completed a measure of explicit weight bias (Fat Phobia Scale) to determine whether antifat attitudes are associated with weight-related perceptions of physicians. RESULTS: Respondents reported more mistrust of physicians who are overweight or obese, were less inclined to follow their medical advice, and were more likely to change providers if the physician was perceived to be overweight or obese, compared to normal-weight physicians who elicited significantly more favorable reactions. These weight biases remained present regardless of participants’ own body weight. Inspection of interaction effects revealed opposing effects of weight bias between the obese/ overweight and normal-weight physician conditions. Stronger weight bias led to higher trust, more compassion, more inclination to follow advice, and less inclination to change doctors when the physician was presented as normal weight. In contrast, stronger weight bias led to less trust, less compassion, less inclination to follow advice and higher inclination to change doctors when the physician was presented as obese. CONCLUSIONS: This study suggests that providers perceived to be overweight or obese may be vulnerable to biased attitudes from patients, and that providers’ excess weight may negatively affect patients’ perceptions of their credibility, level of trust and inclination to follow medical advice. International Journal of Obesity (2013) 37, 1415–1421; doi:10.1038/ijo.2013.33; published online 19 March 2013 Keywords: stigma; bias; physician INTRODUCTION Stigma toward obese persons is pervasive in North America. Obese individuals are vulnerable to harmful weight-based stereotypes, including perceptions that they are lazy, lacking in willpower, indisciplined and unintelligent.1,2 These stereotypes give way to stigma, prejudice and discrimination in multiple domains of living, including the workplace, health-care facilities, educational institutions, the mass media and even in close interpersonal relationships.1,3 Of concern, these negative stereotypes have emerged consistently in the health-care setting, with multiple studies documenting biased attitudes toward obese patients by physicians, nurses and other health-care professionals.4–9 Although considerable research has illustrated negative stigma by physicians toward overweight and obese patients (see Puhl and Heuer1 for a review),1 little research to date has examined whether physicians themselves could be vulnerable to weight bias from patients. That is, to what degree do patients hold stigmatizing attitudes toward physicians who are overweight or obese? Given that two-thirds of American adults are either overweight or obese,10 many health care providers also struggle with overweight and obesity11 and may be perceived differently by their patients compared to thinner physicians. This notable gap in research is important to address for several reasons. The provider–patient relationship is pivotal for risk reduction, disease prevention and ultimately disease outcomes for the patient.12 When addressing health behaviors like smoking, exercise, diet and alcohol usage, the provider–patient interaction is key for identifying risk factors and disease, and for counseling patients on appropriate treatment actions.13 Yet, the degree to which these interactions are effective and successful could be related to actual or perceived health-related behaviors of doctors themselves. For example, evidence suggests that physicians with lower resting heart rates are more likely to counsel their patients on exercise14 and non-smoking physicians are more likely to counsel their patients on smoking cessation.15 Some research shows that health professionals of a ‘normal weight’ are more confident in their weight management practices, perceive fewer barriers to weight management for their patients, and have more positive expectations for patient health outcomes.16 Similarly, a Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA. Correspondence: Dr RM Puhl, Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity, Yale University, 309 Edwards Street, New Haven, CT 06511, USA. E-mail: rebecca.puhl@yale.edu Received 19 November 2012; revised 9 January 2013; accepted 16 January 2013; published online 19 March 2013 Physicians’ body weight and patient attitudes RM Puhl et al 1416 recent study found that physicians with a body mass index (BMI) in the ‘normal-weight’ range have greater confidence in their abilities to provide diet and exercise counseling to their obese patients compared to physicians with higher BMI, and believe that overweight/obese patients would be less likely to trust weight loss advice from overweight/obese doctors.17 Personal health behaviors of physicians have also been associated with patients’ perceptions of their decreased credibility.18 For example, one study found that even if physicians talk to their patients about reducing unhealthy behaviors, patients are less likely to listen to physicians who are perceived as unhealthy.19 In addition, experimental research has found that physicians who disclose health, diet and exercise habits are perceived as more believable, healthier and more motivating by patients compared to physicians who do not disclose health behaviors.20 However, the degree to which a physician’s body weight may affect patient perceptions and reactions to physicians remains poorly understood, and has received very little research attention. Of the limited research that has been published in this area, one study found that non-obese physicians are perceived to be better at providing health advice than obese physicians,13 and another study illustrated that patients listen more strongly to the health advice of a non-obese physician, as compared to an obese physician.21 However, questions remain regarding the impact that a physician’s body weight has on patients’ perceptions of trust and credibility of the physician, their comfort level in discussing personal health behaviors, the degree to which they would follow advice to improve health behaviors and even their selection of providers. The present study aimed to assess public perceptions of normal weight, overweight or obese physicians to better understand how these perceptions affect the doctor–patient relationship, including physician selection, physician trust and following medical advice. It was hypothesized that participants would assign more negative ratings on these characteristics to physicians who were described as being overweight or obese compared to physicians described as being normal weight. These questions were examined in an experimental paradigm via an online self-report survey of the general population. This study additionally examined whether certain participant characteristics (for example, gender, age, body weight and race) affect their responses and perceptions of physicians’ weight and the doctor–patient relationship. MATERIALS AND METHODS Participants Participants were recruited from an online database (eLab) hosted by the Yale School of Management (http://elab.som.yale.edu). This website draws from a sample of approximately 20 000 adults from across the United States, who are recruited through advertisements on social networking websites. Registered participants in the panel are notified via e-mail when studies are posted, and they are invited to participate in any studies of their choosing based on the description of the study. The participation was voluntary, and participants were compensated with entry into a raffle to win a gift card. The study was approved by the university’s institutional review board. The authors aimed to obtain a sample of approximately 300 participants, to ensure that each of the three experimental conditions contained at least 100 participants. Three hundred and ninety-one participants completed the survey, of which 33 individuals were removed due to item-nonresponse missing data, resulting in an analysis sample of N ¼ 358. Participants were randomly assigned to the experimental groups (group 1, normal-weight physician: n ¼ 123, 34%; group 2, overweight physician: n ¼ 117, 33%; group 3, obese physician: n ¼ 118, 33%). Participants’ demographic characteristics across conditions were compared using a multinomial logistic regression model with group membership as outcome and age, gender, education, income and race/ ethnicity as predictors. Results showed no differences in participant characteristics across conditions, with the exception of a weakly significant overrepresentation of participants from the lowest educational category (high-school degree or less) in group 1. International Journal of Obesity (2013) 1415 – 1421 Procedure An online experimental survey was developed to assess participant perceptions and opinions of physicians described as normal weight, overweight or obese. Upon agreeing to participate in the study and entering the survey, participants first completed demographic information and general questions about their opinions of physician health behaviors and selecting a physician (see below), and were then randomly assigned to one of three survey conditions. All survey conditions contained identical questions to assess participants’ perceptions of physicians; however, the questions differed according to whether they referred to physicians who were normal weight, overweight or obese. Specifically, in one condition participants were asked their opinions about physicians who are ‘normal weight’, a second condition asked the same questions about ‘overweight’ physicians and a third condition asked these questions about physicians who are ‘obese’. It is important to note that, this classification of body weight of physicians was not objectively defined to participants, and thus, perceptions of what constitutes the descriptors of ‘normal weight’, ‘overweight’, or ‘obese’ could vary across participants. However, previous work has highlighted the important role of individuals’ perceptions in creating the meaning and context within which their behavior is enacted,22 and recent experimental research investigating the subjective categorization of the weight of other individuals (across multiple target and rater characteristics, including gender, race and BMI) found very few significant differences of weight ratings.23 Thus, in order to understand the implications of weight-related perceptions for the doctor–patient relationship (such as physician selection, physician trust or adherence to medical advice), it is informative to assess participants’ subjective perceptions of a doctor’s weight rather than the doctor’s actual weight. For example, if a patient loses trust in the medical advice of a doctor because (s)he perceives that the doctor weighs too much, it is less relevant whether or not the doctor was in fact ‘obese’ by BMI standards. Rather, the importance lies in whether the patient’s perception that the doctor has excess weight influences his/her feelings about the doctor–patient relationship. Measures Demographic and weight information. Participants were asked demographic questions including their age, gender, race/ethnicity, level of education/income, as well as height and weight. Height and weight information were collected to determine the BMI of participants. This information is important for examining responses among individuals within different weight categories. Of the N ¼ 358 participants in the analysis sample, n ¼ 56 participants (16%) had missing BMI data, which were multiply imputed (M ¼ 20) in order to avoid biased estimates. Physician health behaviors. Following demographic information, participants were asked to provide their opinions in response to six questions about their opinions of health behaviors among physicians, with respect to whether doctors should or should not smoke cigarettes, drink alcohol, exercise regularly, eat a well-balanced diet, see a doctor regularly and obtain yearly preventive screenings (for example, ‘In general, doctors should not smoke cigarettes’). Items were presented with Likert rating scale response options (from 1 ¼ ‘strongly disagree’ to 5 ¼ ‘strongly agree’) in order to determine what behaviors participants view as healthy or unhealthy in a physician. Chronbach’s alpha for this measure was 0.81. Physician selection. Participants were then asked five questions about how important a physician’s body weight and physical appearance are when choosing a doctor for themselves (for example, ‘When choosing a doctor, his/her body weight is important to me’ and ‘It is important to me that my doctor is at a healthy weight’). Questions were asked using a fivepoint Likert rating scale (from 1 ¼ ‘strongly disagree’ to 5 ¼ ‘strongly agree’). Chronbach’s alpha for this measure was 0.90. Physician compassion. Following randomization to one of the three survey conditions, participants were asked their opinions about normal weight, overweight or obese physicians. Five questions were asked to assess participants’ perceptions about the compassion and bedside manner of their physician if he or she was normal weight, overweight or obese. Questions specifically asked the degree to which participants believed the doctor would listen carefully to them, understand their concerns and understand the difficulties of losing weight, and the extent that they would feel comfortable talking to their physician and expressing health concerns (for example, ‘I believe a [normal weight/overweight/ & 2013 Macmillan Publishers Limited Physicians’ body weight and patient attitudes RM Puhl et al 1417 obese] doctor would listen carefully to what I have to say’). Higher scores on this measure reflect higher compassion. Chronbach’s alpha was 0.80 for this measure. 31% overweight (BMI 25.0–29.9) and 17% obese (BMIZ30). Average participant BMI was 25.77 (s.d. ¼ 6.29). Physician trust/credibility. Five questions were also asked regarding how much participants would trust the physician, recommend him/her to friends, feel free to express concerns about their body, have doubts about the physician’s credibility or feel embarrassed when talking about losing weight (for example, ‘If my doctor was [normal weight/overweight/obese], I would have doubts about his/her credibility’). Higher scores on this measure reflect greater trust toward physicians. This scale demonstrated very good reliability (alpha ¼ 0.91). Analysis of variance Figure 1 shows means and ANOVA results for participants’ ratings of physician selection, trust, compassion and advice following across experimental conditions. Figure 1a shows mean differences across conditions for participant ratings of whether they would change doctors if their doctor appeared to be normal weight, overweight or obese, respectively. Respondents who were presented with questions describing physicians who were either overweight or obese were significantly more likely to change doctors than respondents who answered questions about physicians of a normal body weight. Similarly, perceived trust/ credibility of physicians was significantly worse for physicians who were presented as overweight or obese, as compared to a normalweight physician (Figure 1b). No significant differences were found across experimental conditions regarding perceived compassion of physicians (Figure 1c). However, respondents reported a significantly higher likelihood of following a physician’s Adherence to physician advice. Ten questions were included to assess whether a physician’s body weight would influence the extent to which participants would follow their doctor’s advice both generally and pertaining to specific health behaviors, including advice about losing weight, making dietary changes, exercising, smoking cessation, limiting alcohol consumption, getting preventive screenings, taking regular medications, and how likely they would believe the doctor’s diagnosis of their health and that the doctor would be able to develop an effective plan to help the patient lose weight (for example, ‘If your doctor was [normal weight/overweight/obese], how likely would you follow his/her advice about losing weight?’). Three of the questions are modified versions of the Medical Interview Satisfaction Scale patient satisfaction survey.24 Higher scores on this measure reflect a higher propensity to follow a physician’s advice. Chronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.93. Explicit weight bias. To assess participants’ attitudes toward obese persons more generally, they were asked to complete the Fat Phobia Scale.25 This scale consists of 14 pairs of adjectives commonly used to describe obese people (for example, ‘active’ versus ‘inactive’, ‘no will power’ versus ‘has will power’). The adjectives are placed at opposite ends of a scale that ranges from 1 to 5. Scores below 2.5 indicate positive attitudes toward obese people, and scores above 2.5 indicate more negative attitudes toward obese people. Coefficient alphas from various samples ranged from 0.87 to 0.91.25 Chronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.92. RESULTS Statistical analysis Analyses of variance (ANOVAs) and linear regression models (ordinary least squares (OLS)) were used to analyze the data. Owing to missing data for BMI in some cases (15.6%), BMI values were multiply imputed (M ¼ 20) to avoid selection bias.26 Predicting missingness in BMI using a binary logit model with all covariates that were used in the regression analyses (Table 2) and all study outcome variables yielded a pseudo R2 of 0.48, suggesting that missingness is strongly conditioned on the variables that were used in our analyses. Thus, BMI and other effects would potentially be biased if observations with missing BMI data were discarded. Instead, we used a linear imputation model with all study outcome and predictor variables in order to predict the missing BMI values, based on simulated parameters from the posterior distributions that were obtained from a model fitted to the available (that is, non-missing) data. Between- and within-imputation variability was taken into account for all subsequent variance estimation by applying Rubin’s combination rules.27 All analyses were carried out using Stata version 11.2. Sample characteristics Table 1 presents a summary of sample characteristics. Of the total sample, 57% of participants were female, 70% of participants were Caucasian, and the average age was 37 years (s.d. ¼ 13.19). Participant BMI was calculated and classified into categories according to the clinical guidelines for overweight and obesity in adults by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institute of Health.28 This showed 3.6% of the sample to be underweight (BMIo18.5), 48% normal weight (BMI 18.5–24.9), & 2013 Macmillan Publishers Limited Table 1. Sample characteristics N % Gender Male Female 153 205 42.7 57.3 Highest educational degree HS Some college College þ 29 117 212 8.1 32.7 59.2 Annual household income Under $25 000 $25 000–$49 999 $50 000–$74 999 $75 000–99 999 100 000 þ 58 79 87 52 82 16.2 22.1 24.3 14.5 22.9 251 23 84 70.1 6.4 23.5 Race/ethnicity White Black Other Weight status Underweight Normal weight Overweight Obese Missing BMI BMI (multiply imputed, M ¼ 20)a Age (years) Item:b physician selection Scale:c trust/credibility Scale:c compassion Scale:c following medical advice Scale:c physician health behavior Scale:c anti-fat attitudes (fat phobia) N % Valid % 11 146 94 51 56 3.1 40.8 26.3 14.2 15.6 3.6 48.3 31.1 16.9 N M s.d. a 302 358 358 358 358 358 358 358 358 25.77 25.71 36.97 2.48 3.55 3.62 3.63 3.85 3.52 6.29 6.32 13.19 1.34 1.12 0.79 0.82 0.70 0.68 0.91 0.80 0.93 0.81 0.92 Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; HS, high school. aMissing values were only imputed for BMI, all other statistics are based on the analysis sample. bLikert scale ranging from 1 to 5. cMean scales based on Likert scales ranging from 1 to 5. International Journal of Obesity (2013) 1415 – 1421 Physicians’ body weight and patient attitudes RM Puhl et al 1418 Table 2. Linear regression models Physician selection Experimental condition NW physician OW physician OB physician BMI Age Females 0.438*** 0.581*** 0.012 0.008* 0.225* Trust Compassion Following advice 0.461*** 0.609*** 0.215 0.246* 0.405** 0.520*** 0.016 0.010** 0.274** 0.008 0.008 0.338** 0.013 0.009* 0.362*** Highest educational degree HS Some college College þ 0.029 0.067 0.044 0.145 0.067 0.046 0.233 0.162 Annual household income Under $25 000 $25 000–$49 999 $50 000–$74 999 $75 000–99 999 100 000 þ 0.064 0.015 0.111 0.307* 0.051 0.004 0.099 0.482** 0.240 0.255 0.356 0.473** 0.047 0.157 0.100 0.230 0.198 0.218 0.411* 0.210 0.375 0.376** 0.524* 0.335** 0.312*** 0.074 0.135* 0.039 0.005 0.183*** 0.242 0.316 0.872** 0.762* 358 358 Race/ethnicity White Black Other Physician health behavior Fat phobia Constant 0.372*** 0.107* N 358 358 Abbreviations: HS, high school; NW, normal weight; OB, obese; OW, overweight. Note: ordinary least squares regression models using multiply imputed data for body mass index, M ¼ 20; significance levels: *Po0.05, **Po0.01, ***Po0.001; experimental conditions: NW physician; OB physician; OW physician. Figure 1. Means of outcome measures across experimental conditions and ANOVA results. Note: Each graph in the figure illustrates means of participants’ ratings on the four primary outcome variables across experimental condition: (a) physician selection, (b) trust towards physician, (c) compassion towards physician, (d) following physician’s advice. ANOVA results are presented below each graph; a star indicates statistical significance at Po0.05 with regard to follow-up comparisons using Tukey’s HSD method to account for multiple comparisons, n.s. means not significant at Po0.05; experimental conditions: NW ¼ normal-weight physician, OW ¼ overweight physician, OB ¼ obese physician. International Journal of Obesity (2013) 1415 – 1421 & 2013 Macmillan Publishers Limited Physicians’ body weight and patient attitudes RM Puhl et al 1419 medical advice if the physician was normal weight, compared to physicians who were presented as overweight or obese (Figure 1d). In addition to these main effects, two-way ANOVAs with ‘condition respondent weight status’ interaction effects were estimated. No interaction effects were found, indicating that the differences observed in participants’ ratings across the experimental conditions did not depend on respondents’ own weight status. Regression analyses Table 2 shows parameter estimates for the differences between the experimental conditions, controlled for a number of covariates. Covariates included demographic characteristics, respondent’s BMI, expected health behavior of physician and weight bias. These covariates were included to adjust the experimental group effects with respect to any potentially remaining differences in individual characteristics across experimental groups. For physician selection, trust/credibility and following advice, differences in scores amounted to approximately 1/2 of a standard deviation between the overweight/obese conditions and the normalweight condition, indicative of moderately sized effects. A smaller difference (approximately 1/4 of a standard deviation in the outcome variable) was found for compassion, indicating that after controlling for covariates (see Table 2), respondents perceived the obese physician to be less compassionate than the normal-weight physician. This was a small effect, but weakly significant (P ¼ 0.046). To test whether respondents’ own attitudes about obese persons (as measured on the Fat Phobia Scale) affected their opinions of physicians within each experimental condition, we estimated parameters for ‘attitude condition’ interactions, controlling for respondents’ BMI. These results are presented in Table 3, and the condition-specific slopes are graphically presented in Figure 2, which are displayed for average BMI baselines. Given significant BMI main effects for variables of physician selection and trust/credibility, the baselines of these slopes would decrease or increase, respectively, by approximately 3% of a standard deviation in the dependent variable for every one unit increase in BMI. The plotted interaction effect in Figure 2a shows that for respondents in the ‘normal-weight physician’ condition, the physician selection scores decrease with increasing anti-fat attitude scores, while the amplitude of this effect (that is, the difference in the dependent variable over the full range of anti-fat attitudes) amounts to approximately two standard deviations. Conversely, for respondents in the obese physician condition, the physician selection scores increase with increasing anti-fat attitudes. Thus, participants who expressed more weight bias (higher fat phobia scores) were less likely to switch doctors if presented with a normal-weight physician, but more likely to switch doctors if presented with an obese physician. The difference between these two slopes is sizable and highly significant (b ¼ 0.599, Po0.001; the slope for the ‘overweight physician’ condition was not significantly different from that for the ‘normal-weight physician’ condition, see Table 3). Participants who expressed more weight bias (higher fat phobia scores) additionally reported higher levels of trust/credibility and adherence to medical advice when presented with a normalweight physician, but reported less trust/credibility and adherence to medical advice when presented with an obese physician (see Figures 2b and d). A similar effect, although smaller, was observed among respondents who were presented with the overweight physician with respect to following medical advice, although there was no effect of fat phobia scores on trust/ credibility in this condition (although the slope differed significantly from the slope for the normal-weight physician condition). Small effects were also observed for perceptions of compassion among physicians: respondents with higher levels of weight bias perceived normal-weight physicians to be more compassionate, with the slope being significantly different from the slopes for both the overweight and obese physician conditions. DISCUSSION To our knowledge, this study is the first to experimentally assess public perceptions of normal-weight, overweight, or obese Physician selection Trust 2 Trust, z-scores Physician selection, z-scores 2 1 0 –1 –2 0 –1 –2 –2 0 2 Fat Phobia scale, z-scores NW phys. OW phys. –2 OB phys. OW phys. OB phys. Following advice Compassion 2 0 2 Fat Phobia scale, z-scores NW phys. 2 Following advice, z-scores Compassion, z-scores 1 1 0 –1 –2 1 0 –1 –2 –2 0 2 Fat Phobia scale, z-scores NW phys. OW phys. OB phys. –2 0 2 Fat Phobia scale, z-scores NW phys. OW phys. OB phys. Figure 2. Condition-specific regression slopes for the anti-fat attitudes effect on trust toward physicians. Note. Each graph in the figure illustrates one of the four primary outcome variables: (a) physician selection, (b) trust towards physician, (c) compassion towards physician, (d) following physician’s advice. Plotted slopes reflect the parameter estimates shown in Table 3. Experimental conditions: NW ¼ normalweight physician, OW ¼ overweight physician, OB ¼ obese physician. Outcome and fat phobia variables are z-standardized; higher fat phobia scores indicate more weight bias. & 2013 Macmillan Publishers Limited International Journal of Obesity (2013) 1415 – 1421 Physicians’ body weight and patient attitudes RM Puhl et al 1420 Table 3. Regression models with interaction effects of experimental condition and anti-fat attitudes Physician selection Trust Compassion Following advice 0.461*** 0.637*** 0.495*** 0.664*** 0.190 0.184 0.413*** 0.495*** 0.382*** 0.484*** 0.209* 0.172 0.599*** 0.455*** 0.700*** 0.324* 0.315* 0.436*** 0.773*** 0.010 NW physician OW physician OB physician Fat phobia (z-scores) NW physician fat phobia OW physician fat phobia OB physician fat phobia BMI (centered) 0.025** 0.030*** 0.010 Constant 0.365*** 0.390*** 0.129 N 358 358 358 0.255** 0.307*** 358 Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; NW, normal weight; OB, obese; OW, overweight. Note: ordinary least squares regression models using multiply imputed data for BMI, M ¼ 20; BMI is centered around its mean in each of the 20 imputed data sets; all dependent variables and the fat phobia scale are z-standardized; significance levels: * Po0.05, ** Po0.01, ***Po0.001. Interpretation: constants reflect the mean of the dependent variable for respondents with an average BMI in the normal-weight doctor condition, and the fat phobia effect reflects the anti-fat attitude slope for respondents in that condition; the OW physician fat phobia and OB physician fat phobia effects reflect the differences in anti-fat attitude slopes between the overweight and obese doctor conditions, respectively, and the normal-weight doctor condition. The experimental condition main effects reflect the differences in baselines between the three experimental groups. physicians and how these weight categories (and personal attitudes about obese persons) affect public opinions about the doctor–patient relationship such as physician selection, physician trust and following medical advice. Findings show that there is a negative weight bias toward physicians who are perceived to be overweight or obese. Specifically, respondents report more mistrust of physicians who are overweight or obese, are less inclined to follow their medical advice and are more likely to change providers if their physician appeared overweight or obese, compared to normal-weight physicians who elicit more favorable opinions from respondents. These biases remained present regardless of participants’ own body weight, and were more pronounced among individuals who demonstrated stronger weight bias toward obese persons in general. While health providers have been documented to hold negative attitudes and stereotypes toward their obese patients (see Puhl and Heuer1) this study indicates that if providers are themselves struggling with excess weight, they too may be vulnerable to weight bias from patients. Previous research shows that health behaviors modeled by providers may have important implications for the adoption of healthy, or even unhealthy, behaviors of patients.20,29 Our findings add to this literature, suggesting that a provider’s body weight may lead to biased perceptions by patients that could impair the quality of patient–provider interactions and potentially even patient compliance with their provider’s health advice. The fact that participants responded negatively to excess weight among health providers without the provision of any additional health information about the provider further suggests that participants made assumptions about the health status and health behaviors of the physician based on body weight alone. Stigma-reduction efforts to reduce weight bias among health professionals have emphasized the importance of challenging stereotypes and recognizing the complex etiology of obesity as determined by multiple genetic, biological and environmental factors, rather than simply personal willpower or discipline to engage in healthier lifestyle behaviors.30,31 It may be that similar approaches are needed to educate patients (and the general public) about weight bias, to help challenge stereotypes that could ultimately threaten provider–patient interactions and the extent to which patients follow advice and feel comfortable discussing their own health concerns. International Journal of Obesity (2013) 1415 – 1421 Interestingly, findings revealed that there is more similarity across experimental conditions regarding perceived compassion and bedside manner of physicians, such as a physician listening carefully to the patient, understanding the patient’s health concerns and the difficulties of losing weight, and creating a comfortable environment for patients to express their health concerns. This suggests that a physician’s excess body weight may have less impact on a patient’s perceptions of his/her bedside manner or ability to understand and listen to the patient, but may nevertheless threaten patient perceptions of their credibility, level of trust and inclination to follow medical advice. In light of the present findings, it seems warranted to examine whether providers perceive these biases from patients, and to what extent they feel weight bias influences their effectiveness in delivery of health care or the quality of interactions with patients. Findings from the present study raise several additional questions that warrant research attention. First, it is unclear whether or not a physician’s body weight would affect patient adherence to medical advice beyond advice related to weight management and health behaviors. It may be that weight biases from patients toward overweight or obese physicians are most pronounced for medical advice that specifically addresses weightrelated health, but less so for medical advice related to other aspects of health. It will be informative for additional research to examine these issues. Second, as considerable disease management is performed by nurses and health professionals other than physicians, it will be important to examine whether similar findings are observed toward overweight or obese nurses, dietitians, psychologists, and other health providers. Several limitations should be noted. The cross-sectional nature of the study precludes causal inferences from the present findings. Given that participants’ reactions were assessed via self-report, it will be important to examine whether weight biases by patients toward providers affect actual patient outcomes such as their selection of physicians or adherence to a provider’s medical advice. In addition, participant weight and height were selfreported; however, research indicates high concordance between objective and self-reported measures of height and weight for adults.32 The weight distribution in the present sample contained a higher percentage of individuals with a BMI in the normalweight range compared to the general US population, so it would be useful to assess perceptions of physicians’ body weight in & 2013 Macmillan Publishers Limited Physicians’ body weight and patient attitudes RM Puhl et al 1421 samples with more individuals in higher weight categories. Finally, it will be important to identify whether similar weight biases emerge in a more ethnically diverse sample, and whether attitudes differ according to whether the provider is a male or female, or among parents seeking treatment for children with nutritional or weight-related issues. In conclusion, this study suggests that providers perceived to be overweight or obese may be vulnerable to biased attitudes from patients, and that providers’ excess weight may negatively affect patients’ perceptions of their credibility, level of trust and inclination to follow medical advice. More research is needed to understand the prevalence of patient weight biases and the impact these have on providers, patient–provider interactions and patient outcomes. Given that both patients and providers struggle with excess weight, and that weight stigmatization remains a socially acceptable and prevalent form of bias,1,33 efforts are needed to reduce weight bias in the health-care environment to help remove barriers that may otherwise interfere with providers’ provision of care and health-care experiences for patients. CONFLICT OF INTEREST The authors declare no conflict of interest. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This research was supported by a grant from the Rudd Foundation. REFERENCES 1 Puhl R, Heuer CA. The stigma of obesity: a review and update. Obesity 2009; 17: 941–964. 2 Puhl RM, Brownell KD. Bias, discrimination, and obesity. Obesity Res 2001; 9: 788–905. 3 Brownell KD. Introduction: The Social, Scientific, and Human Context of Prejudice and Discrimination Based on Weight. Weight Bias: Nature, Consequences, and Remedies. Guilford Press: New York, pp 1–11, 2005. 4 Brown I. Nurses’ attitudes towards adult patients who are obese: literature review. J Adv Nursing 2006; 53: 221–232. 5 Huizinga MM, Cooper LA, Bleich SN, Clark JM, Beach MC. Physician respect for patients with obesity. J Gen Intern Med 2009; 24: 1236–1239. 6 Huizinga MM, Bleich SN, Beach MC, Clark JM, Cooper LA. Disparity in physician perception of patients’adherence to medications by obesity status. Obesity 2010; 18: 1932–1937. 7 Puhl RM, Brownell KD. Confronting and coping with weight stigma: an investigation of overweight and obese adults. Obesity 2006; 14: 1802–1815. 8 Price JH, Desmond SM, Krol RA, Snyder FF, O’Connell JK. Family practice physicians’ beliefs, attitudes, and practices regarding obesity. Am J Prev Med 1987; 3: 339–345. 9 Schwartz MB, Chambliss HO, Brownell KD, Blair SN, Billington C. Weight bias among health professionals specializing in obesity. Obes Res 2003; 11: 1033–1039. & 2013 Macmillan Publishers Limited 10 Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999–2010. J Am Med Assoc 2012; 307: E1–E7. 11 Manson J, Willett W, Stampfer M, Colditz GA, Hunter DJ, Hankinson SE et al. Body weight and mortality among women. N Engl J Med 1995; 333: 677–685. 12 Ong L, de Haes J, Hoos A, Lammes F. Doctor-patient communication: a review of the literature. Social Sci Med 1995; 40: 903. 13 Hash RB, Munna RK, Vogel RL, Bason JJ. Does physician weight affect perception of health advice. Prev Med 2003; 36: 41–44. 14 Rogers LQ, Gutin B, Humphries M, Lemmon CR, Waller JL, Baranowski T et al. A physician fitness program: enhancing the physician as an ‘exercise’ role model for patients. Teaching Learning Med 2005; 17: 27. 15 Pipe A, Sorensen M, Reid R. Physician smoking status, attitudes toward smoking, and cessation advice to patients: an international survey. Patient Educ Counsel 2009; 74: 118. 16 Zhu D, Norman IJ, While AE. The relationship between health professionals’ weight status and attitudes towards weight management: a systematic review. Obesity Rev 2011; 12: e324–e337. 17 Bleich SN, Bennett W, Gudzune K, Coope L. Impact of physician BMI on obesity care and beliefs. Obesity 2012; 20: 999. 18 Smith DR, Leggat P. An international review of tobacco smoking in the medical profession: 1974–2004. BMC Public Health 2007; 7: 115. 19 Hull S, DiLalla L, Dorsey JK. Prevalence of health-related behaviors among physicians and medical trainees. Acad Psychiatry 2008; 32: 31–38. 20 Frank E, Breyan J, Elon L. Physician disclosure of healthy personal behaviors improves credibility and ability to motivate. Arch Fam Med 2000; 9: 287–290. 21 Feller DB, Hatch R. Do physicians take care of their health? Physicians’ personal health behaviors, good or bad, can influence their patients. Psychiatr Ann 2004; 34: 762. 22 Combs A, Snygg D. Individual Behavior: A Perceptual Approach to Behavior. Harpers & Brothers: New York, 1971. 23 Yanover T, Thompson J. Weight ratings of others: the effects of multiple target and rater features. Body Image 2010; 7: 149–155. 24 Kinnersley P, Stott N, Peters T, Harvey I, Hackett P. A comparison of methods for measuring patient satisfaction with consultations in primary care. Fam Pract 1996; 13: 41–51. 25 Bacon JG, Scheltema KE, Robinson BE. Fat phobia scale revisited: the short form. Int J Obesity 2001; 25: 252–257. 26 Enders CK. Applied Missing Data Analysis. Guilford: New York, 2010. 27 Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Sample Surveys. Wiley: New York, 1987. 28 National Heart L, and Blood Institute. How are overweight and obesity diagnosed? 2011http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/obe/diagnosis.html (retrieved 21 December 2011). 29 Ubink-Veltmaat LJ, Damoiseaux RAJM, Rischen RO, Groenier KH. Please, let my doctor be obese. Diabetes Care 2004; 27: 2560. 30 O’Brien KS, Puhl RM, Latner JD, Azeem SM, Hunter JA. Reducing anti-fat prejudice in preservice health students: a randomized trial. Obesity 2010; 18: 2138–2144. 31 Danı́elsdóttir S, O’Brien KS, Ciao A. Anti-fat prejudice reduction: a review of published studies. Obesity Facts 2010; 3: 47–58. 32 Kuczmarski MF, Kuczmarski RJ, Najjar M. Effects of age on validity of self-reported height, weight, and body mass index: findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. J Am Diet Assoc 2001; 101: 28–34. 33 Puhl RM, Andreyeva T, Brownell KD. Perceptions of weight discrimination: Prevalence and comparison to race and gender discrimination in America. Int J Obesity 2008; 32: 992–1000. International Journal of Obesity (2013) 1415 – 1421