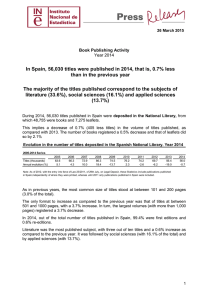

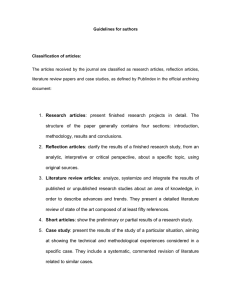

"To Reconcile Book and Title, and Make 'em Kin to One Another": The Evolution of the Title's Contractual Functions Author(s): Eleanor F. Shevlin Source: Book History , 1999, Vol. 2 (1999), pp. 42-77 Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.com/stable/30227296 REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.com/stable/30227296?seq=1&cid=pdfreference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Book History This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms "To RECONCILE BOOK AND TITLE, AND MAKE 'EM KIN TO ONE ANOTHER" The Evolution of the Title's Contractual Functions Eleanor F. Shevlin For it is an antient [sic] maxim of the law, that no title is completely good, unless the right of possession be joined with the right of property; ... And when to this double right the actual possession is also united, . . . then, and then only, is the title completely legal. (Blackstone Commentaries [1765-69])1 "What use, what profit, what account it turns to, what 'tis good for: how it answers the Name; how to reconcile Book and Title, and make 'em kin to one another," ponders John Dunton in A Voyage Round the World (1691).2 Without a doubt, Dunton, the late seventeenth-century anything-but-staid author and bookseller/publisher,3 understood the business of titles. He knew that the title as a complex device performed many more functions than simI am grateful to the 1998 Folger Evening Colloquia for the opportunity to present an earlier version of this essay. I would also like to thank Peter W. M. Blayney, Jonathan Rose, the anonymous readers of Book History, Vincent Carretta, and William Sherman for reading earlier drafts of this essay and commenting with care and intelligence. I am especially indebted to Calhoun Winton and Paula McDowell not only for responding so insightfully to earlier versions of this work but also for their unfailing, generous support of the larger project from which this article is drawn. This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms "To RECONCILE BOOK AND TITLE.. ." 43 ply identifying texts, and that the effective rec text could foster success for the work at several cates, the eighteenth-century British jurist Will stood titles. Blackstone, however, was not concer rather with the title as a legal term that design While these two senses of this English word-its legal one-occupy distinctly separate realms, his In these overlaps, the textual title often emerges title's function as a claim to property. The evolut tionship in England coincided and, at times, int ment of the textual title's function as a commercial and aesthetic device. These collective developments resulted in the acquisition and institutionalization of the textual title's modern contractual nature. Recognizing and understanding the emergence of the title's modern contractual roles can cast new light on titles as a field and on the ways titles can serve as an investigative tool for print scholars, literary theorists, and cultural historians. Today we have internalized the textual title's diverse roles, often over- looking the ways that titles influence us. Framing one's approach as it shapes perceptions of the text, a title can evoke an entire tradition, or it can simply allude to a single work. A title can serve as an urtext, as when an author has only a title from which the whole story will originate. The title can supply a context, as in "What the Bullet Sang," a title that situates its poem's ensuing action on a literal battlefield of war rather than on the barren fields of a love lost. The title can act as a pretext, as when a title compels a browser to buy an unfamiliar work by an unknown author or when a title deliberately misleads, as in the case of the eighteenth-century author who named his moral essays La Jouissance de soi-meme in hopes of attracting and then reforming libertines. Or the title can function as a subtext, as when the title creates a pervasive motif either by literally resurfacing from time to time in the text or by providing an overriding allusion to another work, tradition, or situation. Titles effect implicit contractual relationships with readers, authors, and publishers. Unlike a frontispiece, which may well visually encapsulate the themes of the text that follows, the title of a written work is made wholly of verbal matter and thus is identical to the material that forms the text. Yet the title also enjoys an external as well as internal contractual relationship with the text it labels. Whether its distance from the text it names is as close as a book's spine or as removed as a question in a conversation about what one has lately read, the title participates in the world outside that text. Situated on the border of the text, the title commands a far larger audience than the actual work that it labels-a location that presents vast opportunities for its participation in cultural arenas. By casting such a wide contractual net, titles embody the potential to illuminate This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 44 BOOK HISTORY not just individual works, publishing practices, market Titles, however, did not al study, the title offers severa teenth century marks the t the word "contract" and it that titles enact between re and legal connotations reson ment. The particular suitabi tionship that developed bet from titles acquiring a com this acquisition occurred dur when titles secured an insti cation of their commercial distribution networks, the marked expansions of read an industry, and the evolut to an even greater commer following the invention of 1799 thirty-four statutes r to just five statutes from 1 experienced during this cen tention to these changes.5) of the book during the fina middle decades of the eigh marketing tool as it helped texts. Investigating how and why titles came to shoulder these respo can richly augment our understanding of literary history and t role books have played in time. Many scholars have recommende suit of such a study.6 Derrida, Adorno, and Genette7 have su (though briefly) theorized about the title. Yet the title's develo practice and the theoretical underpinnings of these practices hav surprisingly scant attention.8 The late Stanley Morison once as the history of the title page charts to a great degree the history of Studying the history of the title offers an even broader histori With a history intimately tied both to pre-Gutenberg manuscr printed works, the title proffers a means of exploring the history o physical, aesthetic, and cultural objects from antiquity to the p account of the title before it acquired its roles as a sophisticated vehicle, authorial aesthetic device, and a formal tool of the law This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms "To RECONCILE BOOKAND TITLE.. ." 45 how contractual relationships gradually formed b bels and what the title gained through assuming Titles: Their Evolution, Early and Original Functions Typically chosen arbitrarily and thus lacking co the title in antiquity seems to have operated for t cation. Writing about Old Testament texts, Thom erything in Ecclesiastes was Solomon's "ex Inscriptions ... which ... seem to have been made That early textual labeling existed exclusively to important implication about the title as entity: th cally determined notion whose appearance is close of its contractual functions. In other words, pro ing function, an authoritative status, or a contra ent attributes of titles, but rather are features ascri Titles functioned primarily as denotative conv cepts such as authorship and publication lacked c The appearance of the creator's name in titles poi the ensuing role titles would play among writer, The Gospel According to Saint Luke, Cicero de A creon provide just a few examples. The incorpor as a predominate part of the title persisted for 1651, Thomas Hobbes felt a need to remind reade the subject is marked, as often as the writer."10 I opment, the penchant for including the author's enduring stage in its history. In terms of print cult trend furnishes a concrete historical record from which to reconsider what Michel Foucault has deemed the "author-function."11 The placement of the title proper remained haphazard until the appearance of the title page between 1475 and 1480. The codex, which emerged between the second and third century, had continued the practice of beginning immediately with the text itself.12 Copying faithfully the look of these manuscripts, the first printed books also started with the actual text and omitted any prefatory information detailing the work's name, authorship, date, or publisher. Although titles during this time could appear elsewhere, they were most often found at the end of the work, in the colophon,13 along with other publishing information pertinent to the given work. Here titles This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 46 BOOK HISTORY typically adhered strictly to shared space with informati be bought or with other, es touted the printer/publisher from a 1485 colophon illust taught by the Frenchman J Cease ye, Venetians, sending them to others."14 Far from r references to Venetians, a F score the tensions and comp a product in the marketplac other promotional moves wo rather than its back door. T ensconced feature of books, merly was the colophon's pr Within title title sixty page page years brought helped or the so of t title transform l w izing the book as a physical printing, the title page effe dardization. By heralding th identified the book as a com for the book's production in manufactured object. As cop encapsulated this production of relationships among creat these associations as interac ucts. Before the advent of title page, readers had enjoyed a more relationship with authors. The incipit, common in medieval ma and early printed books, featured an author directly addressing readers, an address informally announcing what the text wo Works like Everyman and Chaucer's Canterbury Tales that "Here begynneth . . ." typify this practice. Incipits behaved lik tional markers that featured authors introducing readers to th matter. This behavior was especially pronounced in manuscripts numerous texts. Unlike the colophon, the incipit's extinction c cancy that only the title, and not the title page as a whole, cou title page formalized, as it made less intimate, the initial encou readers, accustomed to being greeted by the incipit, had with texts. Often promoting the publisher (or printer or bookseller) o early title pages created situations in which the presence of th This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms "To RECONCILE BOOKAND TITLE..." 47 intervened between the reader and the text and trast, not only introduced the text, but it offe discourse about the text at hand could transpir turies before the title would fully sustain its voice, but the potential for such vocalization ne title as part of the title page replaced the incipit. Akin to the direct addresses that the incipit a that were prevalent before printing matured author (or, as frequently was the case, the read logues of sorts. Walter Ong has discussed how and incunabular periods regularly involved phr (on) to form incomplete statements; these frag complete the title by supplying the missing u or the like.16 As Ong points out, here was "a w of a book is less an object, a 'thing,' than a bi he concludes his discussion by noting how the verted this aural world to a visual one: "Boo were becoming objects . .. or receptacles with tacles, they will imperceptibly drift, to some exte course, where they had been moments in dialo ever before, objects in a world of space approa sion" (313). According to Ong, titles took part becoming "detached labels" that were, "typica case, and, specifically, nouns which are not mer discourse but which directly 'stand for' the b While Ong's assessment is accurate in many r titles as detached labels and books as receptacl brought about by printing obscures rather than vative here. Printing did not invent the book detachable label. But it did work to transform the nature of the book as object and the function of the title as the book's free-floating sign. The earli- est known form of titles were literally detached labels affixed either to rolls or to the receptacles in which the physical contents (that is, the book rolls themselves) were stored. The title's role as a separate label in ancient book rolls differs markedly from its later role as a detachable textual feature. If divorced from the book roll, the label lost its value; it could no longer function as an identifier of the roll's contents. Yet in the aftermath of the inven- tion of printing, as innovations in book production and distribution fostered a broader desire for and increased the availability of books, titles became not only a way of identifying and describing texts but also a procedure for advertising and disseminating works in the public arena. Before printing changed the parameters of production, one could have a This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 48 BOOK HISTORY copy of a work made as lon was accessible. The cost diff each additional copy was work-setting the type, dres contrast, a different pricing of a work cally mattered. produced in In fact, large t nu form.17 While one could com with ease as long as an existi necessitated either a proven could be generated, or an ex ented production concerns t importance of fostering a de precedent for how to mark faced with inventing ways t tool that identified texts, t by assuming the additional hawking a work. Thus, not printed word as a formidabl tion that this technology en the title page as a permanen the title's roles. Titles and the Visualization of the Verbal The title's ability to circulate without its text in tow made it an invaluable tool for accomplishing several tasks that all required the title to act as a stand-in for the work. As books came to function more and more as com- modities, their titles also acted as harbingers for the works they identified. Posted on booksellers' stalls, mounted in cleft-sticks, hung over shop doors, tacked on public posts, and even pasted on church doors, the title page acted as a flyer for advertising forthcoming and already available works. Publishers (or their hirelings) first began posting title pages in the late sixteenth century, and the tradition extended well into the eighteenth century as the long written record documenting this practice attests. For whether it is Ben Jonson bemoaning having "my title-leaf on posts or walls, / Or in cleft-sticks,... "18 or Alexander Pope scoffing at Bernard Lintot's "rubric post"19 and exclaiming "What tho' my Name stood rubric on the walls? / Or plaister'd posts, with Claps in capitals?"20 references to posting title pages repeatedly crop up throughout this period. Of the hundreds, and in This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms "To RECONCILE BOOKAND TITLE..." 49 some cases possibly thousands of extra title pages p many were destined for distribution and display matter where they were exhibited, title pages duri phasize, more than even the works themselves, ho as "objects in a world of space approached chiefly i 313). The idea of a book as a viewable object in space, as Ong acknowledges, existed before printing. Illuminated manuscripts, especially with their elaborately rendered, pictorial initial letters, invited visual contemplation and offer an immediate example of the visual, spatial component of texts that predate printed works. But the book's heightened capacity as a commodity engendered by the introduction of printing prescribed a new role for the visual. Rather than serve simply as a source for reflection or a gloss, the visual acquired a commercial function as well. Title pages led the way in appropriating the visual as a marketing tool. Frequently it was the visual aspects of title pages that initially tempted potential readers and buyers to examine a work. If detached from its text, as when serving as an advertising flyer, the title page bore the responsibility first of attracting passersby via its visual appeal and then of conjuring up the absent work and inculcating a desire for its presence-making its absence a loss that could be assuaged only by the material presence and subsequent purchase (or so publishers fervently hoped) of the actual book. Yet while the title page's reliance on the visual to hook prospective readers and purchasers advanced the book as a commodity, this same reliance inhibited, at first, the development of the title as a hook in its own right. Although the title occupied a standard location by the end of the first quarter of the sixteenth century, the types of contracts it effected were only in the fledgling stages. Whether engulfed by ornate title borders, overshadowed by copy promoting the publisher (as well as booksellers and printers), or broken up by indiscriminate segmentation and scaling, the title itself could easily elude a potential reader's fleeting glances. That some titles were awash in such seas of distractions is symptomatic of their function at the time. Writing in 1613, Thomas Dekker comments, "The title of books are like painted chimnies in great country-houses, make a shew afar off, and catch Trauellers' eyes; but comming nere them, neither cast they smoke, nor hath the house the heart to make you drinke."21 Not only does Dekker's complaint indicate the prevalence of titles erecting facades that belie a work's actual content, but his analogy, by treating titles in the primarily visual terms of painted chimnies, also suggests the relative insignificance at this time of titles as purely verbal constructs with substantive ties to the texts that they named. On many occasions the words making up a title were broken up, squeezed, and arranged indiscriminately to fit a pattern, as in This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 50 BOOK HISTORY the representative but rath presentation, like those of m first half of the seventeenth visual temporarily held over This emphasis on the visua world was perceived and un appearance of "speculum" an vides a rich illustration of m charts the history of the mi tween 1500 and 1700 and fu as a prelude to his discussion and literature.23 As Grabes n antiquity, but beginning in t of "speculum," "mirror," an THE BOKE N A- med t1e g~oucrnour,b~te Suyfedbyf fr omas fElot knigIzt. Figure 1. (Reproduced by Permission of the Folger a-CT-- 5 34 Shakespeare Library) This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms "To RECONCILE BOOKAND TITLE..." 51 frequent until its peak during the middle decades Although mirror-titles would later develop de tions with certain kinds or genres of texts, it is f the mid-seventeenth century the use of "mirr titles served as a general substitution for the t mon to almost all mirror-titles . .. is the fact t book itself to be a 'mirror.' "24 Rather than r vogue, the immense popularity of mirror-titles ticular nature of knowledge during the centuri ished. Like tropes such as the microcosm or th of book-as-mirror encapsulates Renaissance co vast network of resemblances.25 Language, as not occupy a neutral place outside this networ gral part of this system of correspondences. Th of distinction "between what is seen and what and relation" that, in turn, ends up constitutin in which observation and language intersect t trope epitomized better this intersection of l that of the book-as-mirror. Mirror-titles graced all sorts of texts rangin widely diverse secular works. Instead of textu class or content, these titles announced the per covering resemblances. They proclaimed the p drawing parallels between printed works and m each. That the production of these two commo larity further affirmed the doctrine of corres mirrors required skills in fashioning molds an raw materials of tin and antimony, and these those needed for casting type.27 By presenting th asked readers to "see" the contents-to consider thing shown or reflected. Mirror-titles often readers' role as "viewers" of a given text by as selves and others in the context of its contents folkes. Wherein they may plainly see their mirrour of allegiance. Or a looking-glasse for t reade their duty towards God and their Kin glass, wherein they may behold the frailties an the sun ... (1660) furnish examples of such inv third-person pronouns-"they may behold" o ties"-in these and many other titles strategical themselves from the subject matter and instead terested observers. This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 52 BOOK HISTORY Frequently the title pages f bled the decorative frames s mula that many of these title as it invoked perspective by would enter via the prelimin era featured frames suggest Governor (Fig. 1) supplies a bally expressive of what is highly visual title pages, esp encourages us to treat the g one of its synonyms as ver producers and publishers pl sance modes of thought, the stresses, "mirror-titles, with which is not primarily-or e with producing an aesthetic titles during the final decade with both the growth of narr reality and a move to more tively, these developments p fidence in the ability of wo title's acquiring contractual velopments, this move away tural shift in Western thoug separation of things and wor Titles, The title's Commerci wording throughou predicated on marketing aim tents or provide a name aest In other words, commercial ment of the title's aesthetic r title as a commercial tool at explained by considering wh work to the public. Since pu author but by the publisher sales-and George the not the Wither, trade, rants an at This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms subjectauthor length w abou "To RECONCILE BOOK AND TITLE..." 53 If he [seller of Bookes] gett any vvritten likely to be vendible, whether the Author b publish it; And it shall be contriued and na his owne pleasure: which is the reason, so m forth imperfect, and vvith foolish titles. N bookes such names as in his opinion will m there is little or nothing in the whole vol Tytle.32 Elsewhere Wither points out how unscrupulous practitioners of the trade33 would "without consent of the writers . . . change the name some[t]yms, both of booke and Author (after they have been ymprinted) and all for their owne priuate lucre" (10-11) and how they do not hesitate "when the impression of some pamphlet lyes upon [their] hands; to imprint nevv Titles for yt, (and so take mens moneyes twice or thrice, for the same matter under diuerse names)" (121). In short, Wither identifies the main uses that unprincipled publishers found for the title: assigning titles that bore no relationship to the texts they labeled; altering the author's name or title or both to gener- ate greater interest; and devising new titles and printing new title pages to resurrect old texts, all in the name of increased sales. That books were sold as unbound sheets, enabling publishers (or perhaps booksellers in some cases) to create their own title pages and their own marketing slant, no doubt contributed to these problems in some quarters. Wither's laments about "foolish titles" intimate that as early as the 1620s some thought was being given to the title as a type of promise about what the work would offer. At this time, however, authors retained virtually no control over the names of their works and consequently no control over the promises that titles extended. Instead, the publishers generally held the reins in deciding the nomination by which a text would enter the world. That the publisher's practice of revamping or replacing an author's title at will met with acceptance-or at least was treated matter-of-factly-for much of the century stems from the institutional circumstances surrounding publication. From the 1550s through the lapse of the Licensing Act of 1695, the right to publish printed material was limited to certain individuals by custom of the trade and by law; only members of the Stationers' Company or those retaining royal printing patents could publish works.34 During much of this time, the title operated in its legal sense as a designator of ownership claims. By custom, entry of a work in the Stationers' Com- pany's Register Book marked a person's claim to the exclusive right to publish that work, and entering this claim included recording the textual title of a work. Providing "the only unquestionable evidence of ownership," entrance in the Register Book was not mandatory until the Star Chamber This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 54 BOOK HISTORY decree of 1637 "unambiguou printed thereafter . . . 'shall Company of Stationers.' "35 33), the Stationers' Company copies was legally secured by in the Registers a matter fo rounding entitlement to cop cultural control that publish role that commercial interes That authors typically lac works' published titles did n an entity entirely separate f the title is part of the autho tions and text. A true forer contemporary Ben Jonson s putting such ideas into effect. makes public his authority, person possessive pronouns i tors and compilers common assigning such titles as "To departs from the convention and booksellers at the time; would have bestowed titles such as "To his Booke" or "To his Booke- seller.""37 Yet widespread recognition of the title's function as an auth assertion about given texts developed slowly. While an interest in tit an integral part of texts existed on the part of some (if not many) aut at the time,38 the legal, cultural, and market conditions for them to fo through and effect implicit contracts with their readers via their title not. Expectations that titles glossed a text's subject steadily increas seventeenth century, and with this increase arose a greater emp title's linguistic import. Mid- and late sixteenth-century titles-A Gallery, of gallant Inuentions. Garnished and decked with diuers deuises ... (1578) or The Worthines of Wales: VVherein are mo thousand seuerall things rehearsed:... (1587), to name two39 ployed alliterative patterns to generate notice, but their wording did l reveal the contents of the ensuing text. While seventeenth-century tit relied on methods such as alliteration to catch the potential purch these methods now gestured to providing some sense of what th would offer: A Svvarme of Sectaries and Schismatiqves ... (1641), as true as Steele, To a Rusty, Rayling, Ridiculous, Lying Libell ... the name of "An Answere to a foolish Pamphlet Entituled, A Sw This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms "To RECONCILE BOOKAND TITLE..." 55 Sectaries and Schismatiques" (1641), and Mad out of Fashions, or, The Emblems of these D rhythmic effects of these mid-seventeenth-ce comparable to modern-day advertising jingles, suggested their texts' involvement in contempo versies and turmoil. That sociopolitical upheavals and subsequent breakdowns in printing and trade controls in the 1640s resulted in an unprecedented flow of printed texts into the English marketplace is well known. The interpretation of these events (and ones leading up to and immediately following) and their complex relationships to changing practices surrounding authorship, reading, and publishing as well as notions of censorship and a rudimentary "public sphere," however, are still being articulated and debated.40 While the changes that titles underwent during these years were certainly enmeshed in these sociohistorical developments, they cannot be adequately addressed here. However, two points can be made. First, the flood of print enhanced the need for titles to hone their marketing capabilities and encouraged the increased emphasis on their verbal nature. Second, the types of "implicit social contract between authors and authorities" that Annabel Patterson and others have claimed as being in place at this time41 are not equatable t the title at this stage in its contractual development. While textual titles could be objects of state censorship,42 titles were still functioning as primar- ily commercial tools and not authorized vehicles of textual significance.43 Most seventeenth-century titles either followed an all-inclusive trend or adhered to a snappy headline approach. Lengthy titles acted essentially as a bill of fare, posting a complete list of what the book would serve with vary ing degrees of thoroughness. Offering a ready example, John Bunyan's long standing bestseller was issued into the world as The Pilgrim's Progress from This World to That which is to come: Delivered under the Similitude of a DREAM Wherein is Discovered, The manner of his setting out, His Dangerous Journey; And safe Arrival at the Desired Country (1678). Such titles can be found through the first half of the eighteenth century with those o Daniel Defoe providing particularly well-known illustrations: The Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders, &c. Who was Born in NEWGATE, and during a Life of continu'd Variety for Threescore Years, besides her Childhood, was Twelve Year a whore, five times a Wife (whereof once to her own Brother) Twelve Year a Thief, Eight Year a Transported Felon in Virginia, at last grew Rich, liv'd Honest and died a Penitent, Written from her own MEMORANDUMS. (1722) This content downloaded from ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff on Thu, 01 Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 56 In BOOK HISTORY contrast, the headline-like t racy wording to attract re Times (1645), a nonrisqu6 ex work's contents-general me events-yet does so with a m vealing its specific political approach, alternate or doub Wears the Breeches (printed to sustain their appeal for m headline types of titles, desp of the increased notice accor descriptive relationship to th While both trends served c long titles is especially sugg glish market was. In compar French practice of brevity d has speculated that these diffe tions surrounding the two b faced with a highly competi on advertising to compete, a a full outline of their conten gent state and Parisian guild the French hooks.46 trade Later and in thus the the cent shorter titles. Printer and n to the booksellers' overuse of ments provide more compell duction of the Term Catalog quarterly listings of recently ness; the adoption of period teenth century; Critical of-fare By Review titles the tle's last by in and the es mid-e furnishing quarter functions the of had the ef s noticea Understanding (1690), John cating complex ideas efficie complex ideas, without part case than a bookseller, who unbound, and without titles, ers only That by Locke showing the employs This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms loose titles t "To RECONCILE BOOK AND TITLE.. ." 57 awareness of the title as not just a means of ident enabling one to talk about it, but as a conveyor of well. As titles assumed more and more descriptive tions, some yielding complex, thematic guidelines f the nature of and possibilities for discourse change enablers of discourse, but potential and actual parti as well. In the hands of "publishers," the title serve and control over the work's public appearance. Whe hold of their titles, another sense of the word "cl title as an assertion about how a text should be read on this second sense of "claim," titles create exp they guide readers' textual responses to works. No expansion of the title's claims. Rather publishers, readers all contributed to the title's evolving funct shared awareness that titles generate implicit contr their public. Titles and the Development Contractual Relationships As purely denotative devices, titles primarily ident ing their subject matter. Once titles assumed descri however, they became vehicles of textual meaning channel textual meaning stemmed from authors ass names of their works. In England, titles of works garded as part of the author's province during the seventeenth century. Much work remains to be do the causes and extent of this shift, but changing c including notions of commercial publication as un tainly supply one plausible explanation. What we h sive individualism," Lockean notions of property, about contractual models of society and governme conducive to regarding the title as a contract. By heightened meaning, the shift to authorial contro significant advance in the title's contractual nature gard titles as authorial statements that formed an themselves. Late seventeeth- and eighteenth-century readers title's textual import through increasing literary This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 58 BoOK HISTORY and their functions. A cogen oured Uncle, on his Poem, c entirely on titles as contract Some specious titles fix And tantalize the Read And doth peruse the B Expecting still, th' Hyp But you Sir, to the Title Do all along so close ke That he who reads you Surely each Page thereo Although the writer of this who are fixing "specious tit that he is indeed speaking ab tions of titles are reflected i by titles and the virtue of k In The Unlucky Citizen: Ex fortunes of an Unlucky Lon and author as well as the op brary,5so repeatedly draws a After discussing his choice o to it in his preface, he opens gives his Reason for the Tit paragraph to this explanatio generated by the work's nam tended by the title. Through the existence of this contract a it. The final line of his narra solicits the reader's agreeme conclude with me that hithe full circle, The Unlucky Citiz parts of texts, not just adver Despite the growing sense t mercial role of titles as mark this role became even more sense of raising curiosity and operate (as they still essentia absent property and fluctua time when print was flexing This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms "To RECONCILE BOOKAND TITLE..." 59 modity, the ability of titles to attract and r just the success of an individual work but, incre genres as well. "How to reconcile Book and T another" now involved balancing the title's re with its commercial function. The formative negotiations between these two contractual functions coincided with the appearance of copyright laws and related legal cases that laid the groundwork for significant changes in the book trade's structure and, much later on, for new conceptions of authorship and its accompanying rights.s3 With the passage of the first "copyright"54 act in 1710, one's legal claim of property in a work could and would be recognized only if its title had been registered with the Company of Stationers: . . . nothing in this Act contained shall be construed to extend to subject any Bookseller, Printer, or other Person whatsoever, to the Forfeitures or Penalties therein mentioned, for or by reason of the Printing or Reprinting of any Book or Books without such Consent, as aforesaid, unless the Title to the Copy of such Books or Books hereafter Published shall, before such Publication be Entred [sic], in the Register-Book of the Company of Stationers ... (Act 8 Anne, c. 19/21)ss Although the phrase "Title to the Copy" invokes foremost the legal meaning of the word "title" as a claim of ownership, the assertion of this claim was accomplished by recording the textual title-that is, the name of the book. The Printing Act of 1662 had legislated entry in the Stationers' Company's Register Book, but it did not mention the word "title" in this context. The word's specific mention in the 1710 Act in the context of entries created a situation that encouraged semantic slippage between the two meanings of "title." Moreover, the 1710 Act replaced the issue of textual regulation-by which I mean an emphasis on monitoring both the trade and what is printed-with conceptions of textual property. This move to "textual property" shed previous overtones of supervision (as exercised inter- nally by the Court of Assistants, a ruling body within the Stationers' Company) and censorship (as exercised externally by the government and Crown) and placed weight instead on the text as a form of property to be protected.56 Thus, the title secured its official status as an indicator and protector of property claims in the legal realm at roughly the same moment that it was expanding its capacity for evoking tacit contracts among publishers, authors, and readers in the marketplace. These dual occurrences heightened the importance of the title as a device.57 During the sixteenth and first half This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 60 BOOK HISTORY of the in particular seventeenth centuries classes of boo almanacs, and the like.58 But vidual ownership of copies presses and provincial printe Stock contributed to the em ing the latter part of the seve teenth, very valuable litera titles produced by renowne Dryden, and Pope.59 As the title assumed new functions and underwent the institutionaliza- tion of its newer and older roles, the relationships among these various roles became considerably more complex. Although authors were attending more to their titles and their right to title their works, this contractual development did not mean that writers exercised exclusive power over titling, as remarks by Bertrand Bronson would lead one to believe: "Printers," Richardson once wrote to Aaron Hill, "have often the Honour of being heard in the Business of Titles"; but obviously the author's wishes have primary rights in deciding what the title-page shall contain. Whether it shall be determinative, descriptive, or suggestive; whether to include or omit the writer's name; whether to add a motto, and of what sort: these decisions reveal the author. It was not Bowyer or Lintot who decided for The Works of Mr. Alexander Pope or picked the long Ciceronian motto.60 In reality, Pope's heavy involvement in the press preparations for his Works (1717) did not represent the norm.61 Rather, the growing control and interest that authors were exercising over their titles served to encourage collabo- ration with printers and publishers.62 This collaboration was especially important since readers increasingly expected titles to proffer promises that the ensuing text would fulfill. Since many authors recognized that titles played an important role in selling works, they were often willing to give printers, booksellers, and pub- lishers "the Honour of being heard in the Business of Titles." Some of these voices were louder than others. Defoe's title choices usually correspond to the titles given in the head and running titles of his works. The lengthy additions to his base names-additions that essentially amounted to plot summaries and that can be found on the title pages to his works-reflect the efforts of his congers to ensure sales.63 At other times, especially as the cen- tury progressed, authorial voices and those of publishers engaged in dialogue over titling decisions. The exchanges that we find in correspondence This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms "To RECONCILE BOOKAND TITLE..." 61 between these parties and authors frequently i balance the title's role as an authorial expressio diminishing its usefulness as a marketing devi increasingly treated the title as a contract betw and the work's reading public. Assigning titles appropriate to their works' important ramifications for fulfilling reader not infrequently crops up in exchanges betwe as well as between authors and publishers. A c cation and labels was of course a hallmark of root in the latter decades of the seventeenth ce to explain his choice of generic designation in Year of Wonders, 1666. An Historical Poem" (1 of this concern: "I have call'd my Poem Histor the Actions and Actors are as much Heroick, since the Action is not properly one, nor that cesses, I have judg'd it too bold a Title for a fe Eighty years later, the boldness of "epic" as fuels Samuel Richardson's anxiety over Aaron the Patriot. An Epic Poem as a title. In a 17 expresses his misgivings: As to your ... title ... I have your pardon consideration, whether epic, truly epic, a to call it epic in the title-page; since hundr will not, at the time, have seen your adm word.66 Displaying much tact and a sensitivity to the thor might well harbor for a given label, Rich the embarrassment that he feels might ensue poem as an epic. In Richardson's eyes (the eye knows how works sell), the value that "epic" c bespeaks the assumption of a mastery of (or p well as an adherence to established rules. Unlik record rationalizing his decision to retain "A ascribe "epic" to his poem despite Richardson' to his confidence in his abilities and the label's aesthetic and/or marketing boost that such a we do have on record via this letter is a demonstration of Richardson's understanding of how titles set in motion complex signals between authors, This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 62 BOOK HISTORY their works, and the mark and public tensions at work The letters of publisher/a pation with titles in gener publisher over title choice emerges the strong sense claim to the work in terms tractual terms. Thus we wi ing to Dodsley what he wil I am not at all satisfied publish a Collection of wch too have already be adorned would make m not apprehend, that thi to the Sale of the book. phlet of a shilling or tw customers, whose eye is Very much attuned to mar reputation, Gray rebukes D ate not only because it mis eously targets the impulse bespeak authority, leaving Anticipating Dodsley's bott title change would not pre distinctions between his readers whom a showy titl bearing the title Designs b Gray's mandate, excepting held. In contrast to Gray's conf dence in keeping with a po tle-known George Tymms the experienced Dodsley: I leave little intirely to Pamphlet your to di come an Essay upon Monop Friend.-- ... N.B.: I giv Title page, but This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms every oth "To RECONCILE BOOKAND TITLE.. ." 63 A vicar, Tymms begins his letter by confessing t reluctance [that] I commence Author at this t assuring Dodsley that he will "be accountable to and other Expences or printing" because he is "ve buy, if they cou'd see more of it than the Title." the piece, it appears as an anonymous work bear Monopolies, or Reflections upon the Frauds Wholesale Dealers in Corn and Flour.7' Dropping a Friend," Dodsley forgoes the personal, intimate title. He substitutes a more public and timely al shortages and hoarding that had drawn public an for the past few years,72 striving for more sales an the Gray and Tymms cases demonstrate how th the title, once it achieved a balance with descrip came to participate in the creation of textual mea lar aspects of texts. Readers were not passive parties to these contra discussions about the effectiveness of particular excerpt from an ongoing exchange involving Sam Edwards, a Mr. Wray, and others over the merit for The Feminiad (1754): Your friend Mr. Wray quarrels also with combe's poem; while his father . . . defends "Perhaps," says he, "your friends would not the ... [title], if they had not been disguste poems ending with ad .... " The chief object that it was not clear enough. Perhaps this t objection, The Feminead, or Female Genius, Confirming the era's penchant for glossing subti and the fleeting life of successful formulas that exchange points to the willingness of readers to c revamping the original title. By frequently discussing the names of works, o propriateness, eighteenth-century reviewers enc readers to consider titles while simultaneously pu ers on alert. The Critical Review's evaluation of History of Miss Arabella Waldegrave conclud snidely, "To do our author justice, however, his able; for Miss Arabella Waldegrave's constancy r of the many very extraordinary efforts which a This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 64 BOOK HISTORY tachment favorable en to the man on w report of Histoi France, en Angleterr stresses that the "author t mention'd in his title, to s have his report."75 A Mon Groans of Great Britain, r entitled the groans of Gre will continue such to all, b equal propriety have called these reviewers' discussions is the notion that the textual fulfillment of a title's promises indicates that its text has at least some merit. Spurred in part by public discourse surrounding the evaluation and re- ception of titles, authors continued to discuss and defend their titular choices well into the eighteenth century, and their commentary evinces the growing sophistication of the contracts that titles generated. Such discussions typically occur in the prefatory material, as in the case of Lord Kames, who expounds on why he has omitted the definite article from the title Elements of Criticism;77 or that of John Kidgell, who in the guise of apologizing for his novel's title, The Card (1755), urges the reader to discover its propriety by reading on.7" Lord Kames's emphasis on a seemingly insignificant verbal omission underscores the ways in which a title's individual words combine to form densely packed verbal formulas that embody cultural codes and that make specific promises to readers about textual content. Kidgell's remarks reveal the sophisticated aims that the title's contractual functions could now support. By refraining from shedding light on his title (a title not typical of like fiction of the 1750s, and thus arguably requiring an explanation), Kidgell teases the audience to generate curiosity. His move highlights the title's function as a seductive tool as it invites readers to claim ownership of the title's meaning. Yet the control that Kidgell ostensibly hands over to readers can be gained only if they read his text. With the growing importance of the title's ability to execute diverse roles, these responsibilities in turn placed the title in a double bind of sorts. In The Adventures of an Author (1767), these pressures on the title to act as both an authorial assertion and a marketing tool become part of a chapter's plot. Employing the title as a plot device within the body of the text reinforces the importance that titles held for authors; this plot simultaneously reveals to readers the prominent role a title could play in relationships between authors and their booksellers as each party tries to balance the title's duties. Having had his work accepted, the author encounters Mr. Folio, the bookseller, on the morrow only to find that the piece is now rejected. Folio explains that his ready acceptance was based solely on the work's name, but This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms "To RECONCILE BOOKAND TITLE..." 65 after having perused the manuscript, he discov Upbraiding the author, Folio fumes, ". .. you p seemed one side of the question, and proved t palpable fraud-I might have been ruined and n the trade, published a book without reading tents.""79 A sly dig at the trade, the bookseller's c common charges brought against titles when t fect between readers, authors, and publishers While the failure of some titles to deliver what th miscommunication, in other cases the cause w intentional fraud. The Title as Imposter and G Complaints about titles as marketing ploys"new" titles masking recycled works-had exis Wither and were lodged regularly, well into th such charges in the sixteenth and first half of th ally arose from authorial dissatisfaction with p late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was titles were increasingly performing hermeneut this new role did not eradicate marketing abu authorial interest in titling practices resulted ships with publishers, in which either party co The Adventures of an Author, the bookseller, M having been victimized by the author's use of "you put a piece into my hand, that seemed o proved to be on the other."82 Yet in the same b specifically publishers, for such problems thro they publish: ". . . had I, like half the trade reading a single word of the contents."83 Since marketing tasks, they typically bore the onus in the eyes of authors and other publishers. Re that authors assigned titles and thus tended to The practices of the eighteenth-century pub Curll, who aroused the ire of authors, publishe the complexities surrounding these marketpla share of complaints for titles and title pages more than they delivered to indulge in intent prominently printed a phrase such as "by Mr. This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 66 BOOK HISTORY when it referred to an epig a new title for a slow-sellin could also grudgingly ackn "You [Curll]," says he, "w of Title-Pages (however li a Book) as any Man, I me ers, must have known th have furnished you with Multitude of Purchasers And excel at marketing he signed for Jane Barker's Ex Curll reduced his risks in p mance."86 After presenting New Romance. in Two Parts the Instruction of some You Burney notes how its word elements of the work." It a tures of Telemachus, which McBurney points to the do from that reference: one of text of Tld~maque that Cur selling Barker's work, Curll ects. Beyond marketing go readers also enhanced its ro Barker title, the layers of r ated her text generally with and specifically with a book vernacular version of a classical narrative. Hostility over titles did not place just authors and publishers in opposition. In some cases authors and publishers found themselves pitted against a printer's tampering with titles, as this December 1737 letter published in the Craftsman loudly laments: "[I]f an Author or Bookseller, cannot trust his Title or his Copy to a Printer, without having it pyrated, it must as effectually put an End to the Liberty of the Press as any Law for that Purpose."88 Although this letter was responding to printers who appropriated the titles of newspapers and periodicals, the point that the title signifies an element of control applies equally to altering the names of individual works, whether the texts involved are classified as verse, fictional narratives, or essays. Michael Harris has detailed how printers during the 1730s and 1740s displayed higher levels of independence and played more prominent This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms "To RECONCILE BOOKAND TITLE..." 67 roles in newspaper production than is often r claims he offers three cases, all of which tellin in contests between authors, publishers, and certain publications.90 I should stress that the duplication, recyclin words in creating titles for newspapers and in mon practices and certainly did not always Often the similarities among titles reflected bonding, savvy marketing, or any combinatio the matter of cloning and appropriating title quences in some situations than others. "Py Craftsman letter writer uses to describe prin established titles, and " 'twas a palpable fraud uses to characterize the author's ironic title in tures of an Author. Rather than simply signa contracts generated by these titles, both insta that titles as actual contractual tools elicit by concrete legal charges. While the Folio examp speak more to the breaking of an ethical cont an author or a publisher and readers, the stig certain title maneuverings was often justifiedfenses was difficult. For example, when a pri herself to publish essentially the same newsp the same title but for different financial backe Michael Harris reminds us, "had no legal prot Thus, instead of the ensuing battle being waged usually fought out their claims by taking adve by furnishing notices in the "new" or "old" p the inaugural issue of the Independent London London Journal being dropt, in a manner very of the principal Shares; the Publick is obliged w The Independent London Journalist; which Character the Title bears."92 Although the title had secured its legal role several decades earlier with the passage of the 1710 Act, the parties concerned in these and similar title disputes that occurred through the mid-eighteenth century lacked a legal recourse. Since the title acted as legal evidence for ownership claims, one might be puzzled by the newspaper proprietors' inability to take legal action by claiming a right in their titles. However, much like the title's odd positioning on the border of the text discussed earlier, the title also occupies a peculiar position in the legal realm. While titles came to serve as the guarantor of texts legally, titles themselves could not-and still cannot-be copy- This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 68 BOOK HISTORY righted.93 Those seeking leg intentional misrepresentatio ing fraud or unfair trade.94 In the printers' appropriation o guarantor proved ineffectua ical or newspaper would con sentative for specific copy documents. Moreover, ever s granting legal protection to refused to accord such prot this refusal derives from a Both the frequency with w tory," "life," and the like ap (compared to their texts) m works unrealistic candidates ing.96 And so, without garner a dual role as both the text' acquisition of its modern m seen, the title also came to stand-in for its text, but so text in the marketplace. The Legacy of the The title's assumption of new seventeenth century and the of the eighteenth marked a these developments, especiall tive assertion about its text, t devices with limited descrip legal, marketing, and aesth roles as agents of diverse co not fully mature foundation until was now the lat in pla timeless givens about titles: ings, including at least these of what follows it; (ii) the a (which means, in fact, a com title always has a double fun the title's deictic function, This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms "To RECONCILE BOOKAND TITLE..." 69 stages of the commercialization of the book. tion the most was the emergence of the title's stered by the growing expectation that autho into its own in England during the long eightee Although delivered squarely in the context o comments about titles that open this essay are gence of the textual title's enunciating funct that "no title is completely good, unless the r with the right of property,"98 he unwittingl changes that textual titles were undergoing at no title could be "completely good" as an inte without the belief that titles carried authorial sanction. As the author's "right of possession" as creator of the text became joined with his or her acknowledged right to name that text, then the possibilities for fully recon ciling book and title, and making them aesthetically kin to each other, became a reality. Throughout much of the eighteenth century, the property rights surrounding textual titles were in flux. Not until 1774, when the Donaldson v. Becket ruling lead to the enforcement of the 1710 Act of Anne and the issue of intellectual property came to the forefront, would the author's double right as creator and namer of texts be united with the authorial right of property in his or her intellectual labors. "And when to this double right the actual possession is also united,.. . then, and then only,"99 could the textual title be completely modern in its contractual functions. Notes 1. William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England: A Facsimile of the First Edition of 1765-1769, 4 vols. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979), 2:13.199. 2. John Dunton, A Voyage Round the World (London: 1691), 2.2. 3. Although the modern sense of the word "publisher" as the party who arranges and pays for the publication of text was not the term commonly used in the early book trade in England, I will use it here to indicate the function of arranging and paying for publication. For a thorough discussion of the difficulties in terminology surrounding "printer," "bookseller," and "publisher," see Peter W. M. Blayney's "The Publication of Playbooks," in A New History of Early English Drama, ed. John D. Cox and David Scott Kastan (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997), 389-92. When it comes to the issue of titles, this confusion in terminology only becomes more complex. While the "publisher" would most frequently be the on in control of the name used to usher a work into the world, printers and booksellers (and sometimes one person would fulfill both roles) could on occasion take charge of the title. In the case of printers, the wording of the title could fall under the jurisdiction of production matters. When booksellers decided to move a text that had not been selling well by assignin a new title page and, thus, often a new title in the process, they too were exercising control of the text's name. 4. For an introduction to these developments, see Lucien Febvre and Henri-Jean Martin, The Coming of the Book: The Impact of Printing 1450-1800, trans. David Gerard (London: This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 70 BOOK HISTORY NLB, 1976); John Feather's A Hi and his The Provincial Book Trad University Press, 1985); Marjorie P ing and Sale of Books, 3d ed. (Lon Isabel Rivers, Books and Their Rea tin's, 1982). 5. Statistics are drawn from the to "The English Book Trade and 6. See Hazard Adams, "Titles, T Art Criticism 46.1 (Fall 1987): 7-2 of This Book," in "The Friday Bo nam's Sons, 1984); John Fisher, Alastair Fowler, "Titles," in Kinds Modes (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvar du titre (The Hague, Paris, and Ne dock's Eyes': A Note on the Theor Form, 2d ed. (New Haven: Yale U ping Names: The Poetics of Titles, (Spring 1975): 152-67; Laurence Le ture, ed. Laurence Lerner (Totow Title as a Literary Genre," Moder "Titles," Journal of Aesthetics an "Questions of Entitlement: Some ed. D. C. Greetham (Ann Arbor: more, cism "The 45.4 Role of Titles (Summer in 1987): E U Identif 403-8. 7. See Jacques Derrida, "TITLE (1981): 5-22; Theodor Adorno, "A cholsen, Notes to Literature (Ne "Structure and Functions of the T 720, and "Titles," in Paratexts: Thr Culture, Theory 20 (Cambridge: C and Adorno's remarks could be c outline of the title's functions from 8. The sole entry for titles in th to this subject's current status with suggests promising coverage of th footnote. John Mulvihill's 1994 Iowa), offers an exception, as does ford: Stanford University Press, 19 titles. Both Leo H. Hoek's La marqu furt: Klostermann, 1986) offer boo translated into English. 9. Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, 3.33.421; my emphasis. 10. 11. Ibid., e 3.33.417. Foucault details Counter-Memory, the author-f Practice, ed. Sherry Simon (Ithaca: Cornell Uni ture point, many have focused on This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms "To RECONCILE BOOK AND TITLE ..." 71 ownership and strict copyright rules were established (tow beginning of the nineteenth century)" (124-25) as the moment Yet Foucault (in his typically slippery treatment of dates) al function of discourse dates at least to the Middle Ages if no Roger Chartier rightly points out, his association of this fu misplaced. See Chartier, The Order of Books, trans. Lydia University Press, 1994), 30-32. 12. In History of the Book (New York: Scarecrow Pre passing that by the fifth century "it became a regular practic of the work as well" (26). Yet Dahl's other remarks strongly su proper but rather the incipit. 13. D. C. Greetham's caveat about confusing scribal subscr when dealing with manuscripts is worth noting. As Greetham information directly related to the text's composition and i provide information about place and date of copying the Scholarship (New York: Garland, 1994). 14. Quoted and translated in S. H. Steinberg, Five Hund (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1977), 132. 15. For an overview of these tensions, see James Raven, " 1450-1800," Publishing History 34 (1993): 5-19. 16. Ong, Ramus, Method, and the Decay of Dialogue (C versity Press, 1958), 312. 17. John Feather, English Book Prospectuses (Newton, P 18. Ben Jonson, "To my Bookseller," vol. 8, The Works Esq. (London: Bickers and Son, 1875), 146. 19. Alexander Pope, The Dunciad, ed. James Sutherland, v of the Poems of Alexander Pope, ed. John Butt, 2d ed. (N 1953), 1728A version, 1.35. 20. Alexander Pope, "An Epistle to Dr. Arbuthnot," ed. J ham Edition of the Poems of Alexander Pope, ed. John Butt sity Press, 1953), 215-16. 21. Dekker, Thomas. A Strange Horse-Race, At the end pols Masque ... (London: Printed for losep Hunt, and are t neere Moore-field Gate, 1613), A 3. 22. Elizabeth Eisenstein's assertion that we "need to think to word' " (38) is worth noting here. This remark forms par pering impressions that the printing displaced the visual wi cussing images in a broad sense, her statement that "[a]fter multiplied, signs and symbols were codified; different kind communication were rapidly developed" (38) is relevant to m The emphasis on the visual that many title pages displayed p iconographic communication. See Eisenstein, The Printing rope (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1983). 23. See Grabes, The Mutable Glass: Mirror-Imagery in Ages and English Renaissance, trans. Gordon Collier (1973; C Press, 1982). 24. Ibid., 38-39. Grabes's statistical compilation reveals that during the Middle Ages speculum ranked third in frequency among book titles after liber and summa (19). 25. In furnishing the historical contexts in which the mirror-metaphor prevailed, Grabes asserts that this metaphor's dominance "can be explained both by the nature of the prevailing This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 72 BOOK HISTORY world-view and by the specific n of conceptualizing that marked t cations and correspondences" and of operation than worldviews, M played in the construction of Wes of the seventeenth centuries: "r knowledge of things visible and See Foucault, The Order of Thing Vintage, 1971), chap. 2. Grabes, h account. 26. Foucault, The Order of Things, 39. 27. Frederick G. Kilgour, The Evolution of the Book (New York: Oxf 1998), 85-86. 28. Indeed, Grabes provides many reproductions of mirror-title page inclusion was not just decorative but rather demonstrated the close re verbal and the iconographic (9). 29. By the eighteenth century the ornate borders and pictorials on way to vignettes, that is, small design ornaments; the layout and present had clearly become a decided concern; and even the number and len typical title pages had decreased. This does not mean that the visual Rather, and this is part of my point, the textual was extracted from the visual and set forth in its own right. Illustrations and frontispieces s components to texts that clearly embraced the visual, but their presence accoutrements to the textual and not equal partners in the communica 30. Foucault, The Order of Things, 43. 31. Exactly who assigned a particular title is still hard to determine du authorial complaints, the fact that a single text could bear different t printed it, and other evidence suggest that the bookseller/printer most o course, authors who also possessed exclusive rights to print their wor moot issue. During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, it was gen author owned his or her manuscript and that the printer/bookseller had permission to print before doing so. However, once the author had re script, he or she also relinquished any say over the text. 32. Wither, Miscellaneous Works of George Wither, vol. 1 (The 1872; New York: Burt Franklin, 1967), 121-22; my emphasis. All futur will appear parenthetically in the text. 33. The Scholars Purgatory was "IMPRINTED For the Honest Station 34. As Peter W. M. Blayney asserts, "Neither the author of a text n paper on which it was written had the right to publish, so neither of that right" ("Playbooks," 394). Blayney is working on what will no do tive work about the Stationers' Company in the early modern period den, The Stationers' Company: A History, 1403-1959 (Cambridge, Mas Press, 1960), esp. 31-33; Feather, A History of British Publishing, 29- Piracy, and Copyright (London: Mansell, 1994), 10-36; and Mark Ro ers: The Invention of Copyright (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Universi 35. Blayney, 403. For a thorough explanation of the terms "auth "entrance," the changes in their usage during the early modern period erroneous assumptions that have arisen due to misunderstandings surrou pp. 396-405. 36. Ferry credits Jonson with being the first English poet to exercise This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms "To RECONCILE BOOKAND TITLE ..." 73 name his poems and thus stake claim to his titles (Title to th she distinguishes as having "been exceptionally prominent in of titling in English," all, save Jonson, belong to the nineteent 37. Ferry, The Title to the Poem, 43. A look at Jonson's ti habit of employing the nominative case, tempers somewhat author's attitudes. Rose rightly remarks that Jonson's conce "had to do principally with the integrity of his texts and with (Authors and Owners, 27). As Rose reminds us, Jonson wa Stuart court and promoted the idea of the absolutist state. Yet "my,". "mine," and the like in his titles suggests that he coul conception of the individual as essentially independent and cr that his allegiance to the absolutist court rules out this poss opposition to Milton, "the autonomous private man" (28). No Pensees about an author's use of first-person personal pronou 'My commentary,' 'My history,' etc. resemble those bourgeo are always saying 'chez moi'-'qui ont pignon sur rue, et touj See Les Pensees de Pascal, ed. Francis Kaplan (Paris, 1982), "The Trade of Authorship in Eighteenth-Century Britain," ety, ed. Nicolas Barker (London: British Library, 1993), 129. or situation-that is, Jonson's affiliation with the Stuart court sense of artistic independence-a look at his titling practic yes, contradictory view of Jonson's sense of himself as author 38. A more extended study of authorship through the lens in serious challenges to those who see the roots of the prop dating from the eighteenth century. Along these lines, Cyn colophons to uncover one early sixteenth-century French aut with his publishers. See Brown, "The Interaction between Au Colophons of Early French Imprints," Soundings 23.29 (19 39. As William Roberts explains in his The Earlier Histor Detroit: Gale Research, 1967), late sixteenth-century bookse title-pages, ... The great aim, of course, was to obtain an att often than not was half the battle towards selling out an ed immediate or remote reference to the subject-matter does n material,-or in fact whether it had reference to anything at 40. See Cyndia Clegg, Press Censorship in Elizabethan E University Press, 1997); Shelia Lambert, "State Control of th The Role of the Stationers' Company before 1640," Censor England and France, 1600-1910, ed. Robin Myers and Mich Bibliographies, 1992), 1-32; Annabel Patterson, Censorship tions of Writing and Reading in Early Modern England (M Press, 1984); Elizabeth Skerpan, The Rhetoric of Politics in 1660 (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1992); and Nig tion in England, 1640-1660 (New Haven: Yale University Pr 41. Patterson, Censorship and Interpretation, 17. Elizabeth terson's notion of this social contract in her arguments for during the English Revolution. 42. Both the 1637 Star Chamber Decree for the Regulating Act of 1662 mention the need for the textual title to be lawful but they both do so in the same breath as epistles, prefaces, and dedications. That is, they lump textual titles with other This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 74 BOOK to treat HISTORY the now accepted peculiar labels and as its stand-in. 43. Shelia Lambert has demonstrated how erroneous it is to view the Stationers' Company as an extended arm of state censorship during the years leading up to the Civil War and has also shown the care that must be taken in making claims for extensive censorship. 44. Veylit, "A Statistical Survey and Evaluation of the Eighteenth-Century Short-Title Cat- alog" (Ph.D. diss., University of California Riverside, 1994; Ann Arbor: UMI, 1994), 174 n. 15. 45. Tellingly, in discussing the phenomenon of lengthy descriptive titles, Gerard Genette relies exclusively on English examples, primarily the titles of Defoe's works, and supplies no examples of such titles written in his native French tongue. On a different note, James McLaverty has also speculated that "a long title was advantageous as more adequately defining the book" in terms of registering it as property in the Stationers' Registers ("Questions of Entitlement," 178). Although many works were not registered early on, even a quick glance over the eighteenth-century titles in the Stationers' Registers will confirm that full titles were recorded, thus bolstering McLaverty's hypothesis. 46. Veylit, "A Statistical Survey and Evaluation of the Eighteenth-Century Short-Title Cat- alog," 174 n. 15. 47. Samuel Richardson, The Correspondence of Samuel Richardson, 6 vols., ed. Anna Laetitia Barbauld (London: printed for Richard Phillips, 1804), 1.122. 48. Locke, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, 2 vols., ed. Alexander Campbell Fraser (New York: Dover, 1959), 2:143. 49. Ran: Jones[?], "To his honoured Uncle, on his Poem, call'd Money Masters all things," Money Does Master All Things (York: printed by John White, for the author, and sold by Tho: Baxter bookseller in Peter Gate, 1696), lines 1-4, 11-14. 50. Feather, A History of British Publishing, 57. 51. Kirkman, The Unlucky Citizen (London: Printed by Anne Johnson, 1674), 1-2. 52. Ibid., 196. 53. Harry Ransom's enduring monograph, The First Copyright Statute: An Essay on An Act for the Encouragement of Learning, 1710 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1956), treats the historical roots leading up to the specifics of the 1710 Statute. Lyman Ray Patterson's Copyright in Historical Perspective (Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 1968) examines the roots of Anglo-American copyright laws, including early government control in England, from the stance of a legal historian. The 1980s witnessed a spate of work on copyright fashioned outside the domain of traditional legal studies. Martha Woodmansee initiated this discussion with her essay "The Genius and the Copyright: Economic and Legal Conditions of the Emergence of the 'Author,' " Eighteenth-Century Studies 17 (1984): 425-48. Her work was followed by Mark Rose's "The Author as Proprietor: Donaldson v. Becket and the Genealogy of Modern Authorship," Representations 23 (1988): 51-85, and his Authors and Owners: The Invention of Copyright. Although he is sometimes guilty of errors, John Feather has written the most about copyright's history in recent years. See "The Book Trade in Politics: The Making of the Copyright Act of 1710," Publishing History 8 (1980): 19-44; "The Publishers and the Pirates: British Copyright Law in Theory and Practice, 1710-1775," Publishing History 22 (1987): 5-32; A History of British Publishing; and Publishing, Piracy, and Copyright. 54. The word "copyright" is actually never used in either the Act's title, An Act for the Encouragement of Learning by vesting the Copies of printed Books in the Authors or Purchasers of such Copies during the Times therein mentioned, or its text. However, for ease of reference and following tradition, I will refer to this act by this shorthand. For a discussion of the word's origins and early use, see Donald W. Nichol's "On the Use of 'Copy' and 'Copyright': A Scriblerian Coinage?" Library, sixth series, 12.2 (June 1990): 110-20. While Nichol found This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms "To RECONCILE BOOK AND TITLE..." 75 early eighteenth-century appearances of variations of the "copyright" in relation to intellectual property would not tru century. 55. The Statutes of the Realm Printed by Command of hi in Pursuance of an Address of the House of Commons of G New York: William S. Hein & Co., 1993), 9:256; my emph of the statute, this act is cited as "Act 8 Anne c. 19." In the C (1984), the current official register of English (and, after var utes, "c. 21" is given. 56. As Mark Rose notes, "The passage of the statute m from censorship and the reestablishment of copyright under regulation" (Authors and Owners, 48). 57. Bearing the title "An Act for the Encouragement of L printed Books in the Authors or Purchasers of such Copie tioned," the act arguably addressed, at a very elementary leve authors, readers, and publishers. Yet although it called atte notion that an author had property in his or her text was no the needs of readers in its claims for the "Encouragement of able book pricing, the publishers dominated this legislation act would eventually dismantle what the publishers who p secure-perpetual rights to copies. 58. As P. M. Handover asserts, "The most discerning p sixteenth century] recognized that it would be more advant to a class of books rather than to individual titles. Thus, R John Day the ABC and Catechism, William Seres all books o were the books that brought in the profits. They were also pirated" (27). See Handover, Printing in London from 14 Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1960). 59. Tellingly, many of the cases put before the Privy Co rights to copies during the late 1570s and 1580s involved p Latin grammars-all classes of books--while the most fre cases leading up to and including Donaldson v. Becket all in 60. Bronson, Printing as an Index of Taste in Eighteen New York Public Library, 1958), 20. 61. Indeed, in reading this collection's physical detail alo and responses to his detractors, Vincent Carretta justifiably f for professing Pope's involvement in such matters as titling ages Reflect from Art to Art': Alexander Pope's Collected W Place: The Intertextuality and Order of Poetic Collections, versity of North Carolina Press, 1986), especially 195-96. 62. There were earlier examples of such collaborations or Nashe's second edition of Pierce Penilesse is a letter in whi shorten the title, complaining that it was too long in the f complied: the second edition bears a shorter title. 63. See Rodney Baine, "The Evidence from Defoe's Title 25 (1972): 185-91. 64. As Anne Ferry rightly notes, "Toward the end of the cording to kind began to sort out these confusions [that is and about the audience's familiarity with formal generic cl the preferred style of presentation" (Title to the Poem, 142). This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 76 BOOK 65. HISTORY Dryden, Works of John Dry 1:50. Anne Ferry discusses Dryden's Mirabilis," Ferry provides an astute about his decision to designate it an modest generic claim from accusatio charges of ineptitude for failing to 66. Richardson, Correspondence, 67. Hill had completed this poe evidently only Dramatist, Hill attests three books Projector that the appeared (1913; New manuscript Yo circ An Heroick Poem" as one of two Account of the Lives and Writings York: Garland, 1970), 298. Note th Jacob's work was issued in 1720, fou of the poem was finished, we have n whether Hill at this juncture was c reception, Theophilus Cibber note ers' "; see The Lives of the Poets of Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1968), 5:261 68. James bridge: E. Tierney, Cambridge ed., The University 69. Ibid., 367. 70. Ibid., 366, 367. 71. Ibid., 367 nn. 2, 4. 72. See James Tierney's synopsis of the situation as well as his bibliographical suggestions for further information in ibid., 368 n. 7. 73. Richardson, Correspondence, 3:85. 74. Vol. 27 (June 1769): 471. 75. Vol. 1 (February 1735): 144. 76. Vol. 8 (April 1753): 311. 77. Henry Home, Lord Kames' Elements of Criticism (1762; Anglistica & Americana. Hildesheim and New York: Georg Olms Verlag, 1970), 17. 78. John Kidgell, The Card, 2 vols. (London, 1755; New York: Garland, 1974), 1:viii-ix. 79. Adventures of an Author (London, 1767; New York: Garland, 1974), 1:66-67. 80. Later in this novel, when the narration slips back to first person after a long interval in third, the narrator turns to the volume's own title to solve the dilemma of who is speaking. Yet the title he cites-"The Adventures of an Author. Written by Himself"-lacks the "and a Friend" tag that appears on the title page. Ironically neither the incomplete title nor the full title printed at the start of each volume would necessarily settle the perplexity surrounding who is narrating. 81. Depending on the state of arrangements, authors could abandon one publisher for another if their desires were not being met-just as they do today. When Barbara Graham selected "Women Who Run with the Poodles" as her title (a play upon Clarissa Pinkola Estes's title Women Who Run with the Wolves), word spread among others in the industry before her work was published. Beset by a flurry of negative reaction and indignation, HarperSan Francisco, Graham's publisher at the time, urged her to change the name. Rather than alter her title, Graham switched publishers, and Avon issued the work under the author's desired title ("Wolf Pack," New York Times Magazine, 19 June 1994, 13). 82. Adventures of an Author, 1.66. This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms C Pres "To RECONCILE BOOKAND TITLE.. ." 77 83. Ibid., 1.66-67. 84. Ralph Strauss, The Unspeakable Curll (London: Ch 85. J. H., Remarks on Squire Ayre's Memoirs (n.p.), quot 86. McBurney, "Edmund Curll, Mrs. Jane Barker, and Quarterly 37.4 (October 1958): 387. 87. Ibid., 388. 88. Letter, Craftsman (3 December 1737), 595. 89. Michael Harris, London Newspapers in the Age of Associated University Presses, 1987), 82. 90. Harris, 86-88. 91. Ibid., 88. 92. Independent London Journalist 1 (19 July 1735), quoted in Harris, 86. 93. Although it was published almost half a century ago, Harry Ransom's article "Ownership of Literary Titles" (University of Texas Studies in English, 31 [1952]: 125-35) furnishes a still-useful overview of the legal reasoning used against copyrighting titles from the eighteenth century through the twentieth. I am grateful to Simon Stern for bringing this article to my attention. 94. In The Marketing of Literary Property (London: Constable & Constable, 1933), Herbert Thring explains that one could use copyright law to protect the invasion of one's literary property if the invasion occurred because of the printing of an unauthorized edition, the importing or selling of a foreign one, or the appropriation of another's labor. Yet if one wished to pursue someone selling one's work under the title or name of another, one would turn to Common Law and the statutes governing fraud and fair trade (200-205). 95. As Thring clarifies, copyright law was not applicable because recourse was not based on the registration of the title or its treatment as an invention, but rather in the title's use. Laws governing fraud, on the other hand, would apply since one could receive satisfaction if one could prove that the same title was used to pass off another text as the first work (205). 96. In "Ownership of Literary Titles," Ransom elaborates on these points (127-29), noting how similarities (and even exact matches) in authorial names meant that "possibilities of conflict in name-and-title combinations were big" (127). How might one tell the difference between "The Works of Samuel Johnson" and "The Works of Sam Johnson" or "The Works of Samuel Johnson," when only the first was written by the Johnson? Legally even these combinations could not be copyrighted. Such leeway clearly suited the tactics of a Curll. Legal prob- lems due to such duplication, as Ransom explains, have been kept in check by distances in time between writers, contrasts in choices of genre and general writing careers, and the basic "good will" of authors (127-28 n. 3). 97. Roland Barthes, "Textual Analysis of Poe's 'Valdemar,' " in Untying the Text: A PostStructuralist Reader, ed. Robert Young (Boston: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1981), 138-39. 98. Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England, 2:13.199. 99. Ibid. This content downloaded from 155.210.59.203 on Tue, 16 Jun 2020 12:02:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms