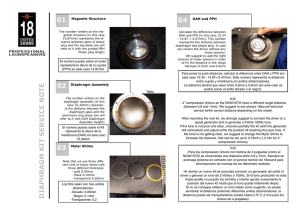

International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics (2005) 89, 236 — 241 www.elsevier.com/locate/ijgo REVIEW ARTICLE The B-Lynch and other uterine compression suture techniques M.S. Allama,T, C. B-Lynchb a Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, South Glasgow University Hospitals, Glasgow, UK Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Milton Keynes General Hospital, Oxford Deanery, UK b Received 5 January 2005; received in revised form 28 January 2005; accepted 4 February 2005 KEYWORDS B-Lynch; Uterine compression sutures Abstract Background: Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) remains among the 5 main causes of maternal death in developing and developed countries, and uterine atony is the most common cause (75—90%) of primary PPH. Uterine compression sutures running through the full thickness of both uterine walls (posterior as well as anterior) have recently been described for surgical management of atonic PPH. Christopher B-Lynch was the first to highlight this revolutionary principle, and other uterine compression suture techniques have since been described by Hayman and Cho. Objectives: Step-by-step description of the B-Lynch brace suture and discussion of the current compression suture techniques. Conclusions: The different uterine suture techniques have proved to be valuable and safe alternatives to hysterectomy in the control of massive PPH, and the present review can make the surgeon better aware of their effective use and the risks they may entail. D 2005 International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics. Published by Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction A blood loss in excess of 1000 mL following delivery, together with the rapidity of the loss, is used as a T Corresponding author. 8 Lanfine road, Ralston, PA1 3NL, Scotland, UK. Tel.: +44 1415612644. E-mail address: allamgoweini@hotmail.com (M.S. Allam). clinical diagnostic tool for major postpartum hemorrhage (PPH). Major PPH occurs in approximately 4% of vaginal and 6% of cesarean deliveries [1]. In a study of 48,865 women who were delivered between 1997 and 1999 in the London area in England, severe PPH was diagnosed in 6.7 per 1000 deliveries [2]; the World Health Organization estimated at 20 million the annual number of maternal complications of PPH [3]; and in the 0020-7292/$ - see front matter D 2005 International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics. Published by Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2005.02.014 The B-Lynch and other compression suture techniques developing world death from PPH, which occurs in approximately 1 per 1000 deliveries [1], accounts for up to 4% of all maternal deaths in the United States [4]. Moreover, PPH was determined by the 2000—2002 triennial Confidential Enquiry Into Maternal Deaths to have played a significant role in 17 deaths in the United Kingdom [5] and it remains among the 5 main causes of maternal death in developing and developed countries [6]. Uterine atony accounts for 75—90% of primary PPH [1]. Different uterine compression sutures have recently been described to control PPH, including a suture that runs through the full thickness of both anterior and posterior uterine walls. Christopher BLynch was the first to highlight this technique [7]. The present review emphasises the special features of the B-Lynch brace suture and provides a comparative discussion of the current compression suture techniques [7—9]. 237 In the case of coagulopathy, if diffused bleeding is controlled by compression, it will also be controlled by the suture. However, application of the B-Lynch suture is not a substitute for the medical treatment of coagulopathy. If the criteria for the B-Lynch suture are met, the uterus remains exteriorized until the suture is completed. The assistant performs uterine compression with both hands throughout suture placement the by the main surgeon. 2.3. Suture application in the case of a low transverse hysterotomy wound 2.3.1. Placement of first stitch relative to low transverse cesarean section wound With the bladder displaced inferiorly, the first stitch is placed 3 cm below the hysterotomy incision on the patient’s right side and threaded through the uterine cavity to emerge anteriorly 3 cm above the upper-incision margin, approximately 4 cm from the lateral border of the uterus (Fig. 1). 2. Methods The procedure was first performed in 1989 by one of the authors (C.B-L.) in a patient who was experiencing massive PPH but refused hysterectomy. The suture aims to exert continuous vertical vascular compression [7,10,11]. 2.1. Surgeon’s position It is assumed that the surgeon is right-handed and standing on the right side of the patient. 2.2. Test for the potential efficacy of the B-Lynch suture before performing the procedure The patient is placed in the Lloyd Davies or lithotomy position. Once laparotomy is performed, an assistant standing between the patient’s legs intermittently swabs her vagina to determine the presence and extent of bleeding. After the uterus is exteriorized, bimanual compression is applied. To do this, the bladder peritoneum is first reflected inferiorly below the cervix; then, the whole uterus is compressed by placing one hand posteriorly with the ends of the fingers at the level of the cervix and the other hand anteriorly just below the bladder that has been displaced inferiorly. If bleeding stops with compression, there is a good chance that the B-Lynch suture will also cause the bleeding to stop. 2.3.2. Fundus The suture material is now carried over the top of the uterus to the posterior side. The suture material should be more or less vertical over the fundus, i.e., lay about 4 cm from the horn (Fig. 2). It does not tend to slip laterally toward the broad ligament because the suture material has been pulled through and the uterus is being compressed, which ensure that proper placement is achieved and maintained (Fig. 2). 2.3.3. Posterior wall The spot on the posterior aspect of the uterus where the suture should be pulled through the uterine wall is easy to determine. It is, on the horizontal plane, at the level of the uterine incision at the insertion of the uterosacral ligament (Fig. 2). The assistant keeps compressing the uterus manually as the suture material is fed through the posterior wall into the cavity. This helps the surgeon pull it through without breakage and allows for maximum compression at the end of the procedure. Furthermore, it minimizes the risk of suture slipping and uterine trauma. The suture material now lies horizontally on the cavity side of the posterior uterine wall (Fig. 2). 2.3.4. Fundus The suture material is pulled again through to the posterior wall (serosal wall), brought over the top of the fundus posteriorly, and then down the anterior left side of the uterus. The needle is now 238 M.S. Allam, C. B-Lynch Figure 1 The B-Lynch suture, anterior view [10]. placed in a position symmetrical to that in which it first entered the right side (i.e., 3 cm above the upper lip of the incision and 4 cm from the lateral side of the uterus), pushed into the uterine cavity and then again through the lower segment, 3 cm below the lower incision margin (Fig. 2). The assistant maintains compression as the suture material is pulled through its different points of entry in a way that ensures uniform tension and no slipping. The 2 ends of the suture are tied with a double throw knot to maintain tension after the lower segment incision had been closed by either the 1- or 2-layer method (Fig. 2). 2.3.5. Relation to the hysterotomy incision Even tension on the 2 ends of the suture material can be manually maintained while the lower-seg- Figure 2 ment incision is closed; alternatively, the 2 ends can be tied before closure and both options works equally well. If the latter is chosen, however, it is essential that the corners of the hysterotomy incision be identified and stay sutures placed before the knot is tied. This ensures that when the lower segment is closed, the corners of the incision are not missed. It is important to identify the corners of the uterine incision to ensure that no bleeding points are left unsecured, particularly because most of the patients undergoing the procedure are hypotensive. Because the knot is low on the lower segment, there is room for wound closure. Because the uterus undergoes its maximum involutionary process in the first week after vaginal or cesarean delivery, the suture probably will have The B-Lynch suture, front view, back view, and knot [10]. The B-Lynch and other compression suture techniques lost some tension after about 24—48 h. Yet, enough hemostasis will have been achieved and there is no need to delay closing the abdomen after the suture placement. The assistant swabbing the vagina can verify that the bleeding has been controlled. 2.4. Suture placement after vaginal delivery If laparotomy is required for the management of atonic PPH, hysterotomy is warranted before placement of the B-Lynch suture. The blind application of the suture can cause obliteration of the cervical and/or uterine lumens and lead to pyometra and morbidity [12]. Moreover, B-Lynch suture application without confirmation that the uterine cavity is completely empty is less likely to be successful. By the time laparotomy begins, even if uterine exploration has been performed, blood clots are likely to have collected within the uterine cavity. Hysterotomy allows to explore the uterine cavity and remove blood clots, retained products of conception, and an abnormally placed placenta. Hysterotomy thus makes proper application of the suture possible, and therefore also maximum, even, and simultaneous compression to both sides of the uterus [11]. 2.5. Application for abnormal placentation The B-Lynch suture may be beneficial in cases of placenta accreta, percreta, and increta. In a patient with placenta praevia, a figure-of-eight or transverse compression suture of the lower segment anteriorly, posteriorly, or both, is applied to control bleeding. If it does not control bleeding, the B-Lynch suture may be placed in addition for hemostasis [11]. 3. Discussion At the time of writing there were 10 reports involving a total of 38 women who had been treated with the B-Lynch surgical technique for severe PPH, with 36 successes and 2 failures [7,13—21]. More than 1000 procedures have been performed worldwide, with only 7 failures reported [10]. The reported causes of failure varied from placenta percreta and uncontrolled disseminated intravascular coagulopathy to lack of suture tension or improper suture application [10]. Three patients underwent laparoscopy at various time intervals postoperatively for sterilisation, suspected pelvic inflammatory disease, and appendicitis. One patient with ileostomy underwent 239 laparotomy for suspected intestinal obstruction 10 days after receiving a B-Lynch suture (unpublished data). Magnetic resonance imaging and hysterosalpingography performed in 1 patient revealed no intraperitoneal or uterine sequelae [17]. No complications have been observed in the 5 patients of the first published series, who have all experienced further pregnancy and delivery [7,10]. The prophylactic application of the B-Lynch suture was performed after cesarean delivery in 15 patients significantly at risk for PPH, and there were no reported complications. All patients were fully counseled about the procedure and its benefits, risks, and implications. Informed consent was signed before surgery (unpublished data). The B-Lynch surgical technique can preserve life and fertility [7], and it has been recommended by various authorities worldwide [5,22—24]. The chances for success of this simple, inexpensive, and quick procedure are uniquely tested immediately before and after its performance, and the procedure can be performed by surgeons with average surgical skills at units with limited resources. Furthermore, with the B-Lynch suture, an even pressure can be achieved at the same time to both sides of the uterine body. With more than 1000 procedures performed worldwide by surgeons of various experience at units receiving widely different financial and clinical support, it is the most frequently used surgical technique for uterine compression. Tied or untied, the suture provides even compression, and thus provides enough space to comfortably close the uterine incision without disturbing the anatomy. A new, user-friendly material is currently used by the authors (Ethiguard blunt needle, half circle, 70-mm in length, with a 90-cm suture [available in violet, code W3709]; Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, USA). The suture material is a poliglecaprone 25 monofilament (Monocryl; Ethicon) whose absorption profile is 60%, 20%, and 0% of the original strength at 7, 14, and 21 days. Mass absorption is complete at 90—120 days. The long blunt needle allows for safe handling and placement. The suture material can be easily and safely adjusted and tightened against the uterine wall. The length of the suture is very convenient for the assistant to maintain a persistent, even compression on both sides of the uterine body while the lower segment incision is being closed by the main surgeon. No adverse effects of the Monocryl filament have been reported, but its long-term effects are not yet clear. The postprocedure patency of the uterine and cervical lumens has been tested [17], and no known postoperative mortality related to the B-Lynch suture has been reported [5]. Furthermore, as it was first applied 240 M.S. Allam, C. B-Lynch in 1989, the B-Lynch suture technique has data from a longer follow-up time than the other uterine compression techniques [10]. As it is now applied at a much lower threshold of suspicion than in the first published series [7], and sometimes prophylacticaly in patients at high risk, competence for its performance will increase. The cost-effectiveness of this procedure may continue to encourage developing countries to consider it for both prophylactic and therapeutic purposes. It is easy to perform after cesarean deliveries and can be used, if necessary, after vaginal deliveries followed by PPH if laparotomy is warranted. 4. Other uterine compression suture procedures Other techniques, such as that described by Hayman et al [8] and the Cho [9] technique of multiple square sutures, were developed to oppose the anterior and posterior uterine walls (Figs. 3 and 4). The Hayman technique is probably quicker to apply than the cho or B-Lynch techniques in cases of atonic PPH following spontaneous vaginal delivery, as the lower uterine segment is not opened, nor the uterine cavity explored. The Hayman technique, however, runs the risk of allowing blood to be trapped within the uterine cavity instead of being expelled freely through the cervix [25]. And the Cho technique, which pierces the atonic Figure 4 The Cho multiple-square sutures compressing anterior to posterior uterine walls [9]. bleeding uterus up to 32 times, may also run the risk of returning the patient to the operating theatre. Moreover, by bracing multiple areas of the uterine body, it could interfere with physiologic uterine involution and may result in blood-filled pockets inside the uterine cavity. The Cho technique has been reported to be associated with pyometra and subsequent hysterectomy [12]. With these 2 techniques, it is not clear how an even compression can be applied to both sides of the uterine body during the procedure. As both techniques are relatively new, worldwide feedback data about safety, efficacy, and subsequent fertility are still limited. 5. Conclusions Postpartum hemorrhage can have diverse causes, but uterine compression suture techniques have proved to be valuable in the control of massive PPH as an alternative to hysterectomy. This review can make the surgeon aware of their effective application, and of the risks and potential complications that they may entail. References Figure 3 The Hayman uterine compression suture without opening the uterine cavity [8]. [1] Mousa H, Alffirevic Z. Treatment for primary postpartum haemorrhage (Cochrane Review). The Cochrane Library, vol. 1. Oxford7 Update Software; 2003. The B-Lynch and other compression suture techniques [2] Mousa H, Walkinshaw S. Major postpartum haemorrhage. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2001;13:595 – 603. [3] WHO report of technical working group. The prevention and management of postpartum haemorrhage. Geneva: World Health Organisation (1999) WHO/MCH/90-97. [4] Pahlavan P, Nezhat C, Nezhat C. Hemorrhage in obstetrics and gynecology. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2001;13: 419 – 24. [5] Department of Health. Why mothers die: report on confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in the United Kingdom 2000—2002. London, England7 RCOG Press; 2004. p. 86 – 93. [6] Dildy G. Postpartum hemorrhage: new management options. Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2002;45:330 – 44. [7] B-Lynch C, Coker A, Lawal A, Abu J, Cowen M. The B-Lynch surgical technique for the control of massive postpartum hemorrhage: an alternative to hysterectomy? Five cases reported. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1997;104:372 – 5. [8] Hayman R, Arulkumaran S, Steer P. Uterine compression sutures: surgical management of postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol 2002;99:502 – 6. [9] Cho J, Jun H, Lee C. Hemostatic suturing technique for uterine bleeding during cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol 2000;96:129 – 31. [10] B-Lynch C. B-Lynch brace suture (technical details). Available at: http://www.cblynch.com/HTML/technique.html. Accessed September 25, 2003. [11] Chez R, B-Lynch C. The B-Lynch suture for control of massive postpartum hemorrhage. Contemp Obstet Gynaecol 1998;43:93 – 8. [12] Ochoa M, Allaire A, Stitely M. Pyometria after hemostatic square suture technique. Obstet Gynecol 2002;99:506 – 9. 241 [13] Smith K, Baskett T. Uterine compression sutures as an alternative to hysterectomy for severe postpartum hemorrhage. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2003;25:197 – 200. [14] Mazhar S. Management of massive postpartum hemorrhage by bB-LYNCHQ brace suture. J Coll Phys Surg Pak 2003;13: 51 – 2. [15] Wergeland H. Use of the B-Lynch suture technique in postpartum hemorrhage. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2002; 122:370 – 2. [16] Vangsgaard K. bB-Lynch sutureQ in uterine atony. Ugeskr Laeger 2000;162:3468. [17] Ferguson J. B-Lynch suture for postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol 2000;95(6 Pt. 2):1020 – 2. [18] Dacus J. Surgical treatment of uterine atony employing the B-Lynch technique. J Matern-Fetal Med 2000;9:194 – 6. [19] Danso D, Reginald P. Combined B-lynch suture with intrauterine balloon catheter triumphs over massive postpartum haemorrhage. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2002;109:963. [20] Steer P. Correspondence. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1999;106:286. [21] Roman A, Rebarber A. Seven ways to control postpartum haemorrhage. Contemp Obstet Gynecol 2003;48:34 – 53. [22] Department of Health. Why mothers die: report on confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in the United Kingdom 1997—1999. London, England7 RCOG press; 2001. p. 94 – 103. [23] Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Placenta praevia: diagnosis and management. Guideline, vol. 27. London, England7 RCOG Press; 2001. [24] Farrell E. Obstetric haemorrhage management guidelines. J Healthc Prof 2002;6:1 – 7. [25] B-Lynch C. Correspondence. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2005; 112:126.