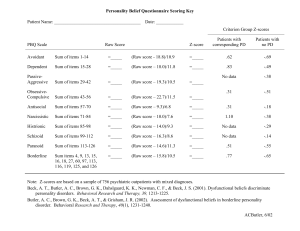

Personality and Individual Differences 116 (2017) 336–342 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Personality and Individual Differences journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/paid The Dark Triad and compassion: Psychopathy and narcissism's unique connections to observed suffering Sherman A. Lee ⁎, Jeffrey A. Gibbons Christopher Newport University, United States a r t i c l e i n f o Article history: Received 30 March 2017 Received in revised form 7 May 2017 Accepted 8 May 2017 Available online 12 May 2017 Keywords: Dark Triad Compassion Empathy Emotion regulation a b s t r a c t Past studies have linked the Dark Triad (DT) traits to dispositional empathy, but not to compassionate feelings in response to observed suffering. To fill this void in the literature, we examined the influence of the DT traits on state compassion using validated film methodology. One hundred and fifty-six college students viewed a movie scene of a distraught child watching his father die. The results revealed that while psychopathy was a negative predictor of compassion for the child, narcissism was a positive predictor. These DT traits explained compassion beyond the contribution of demographics, grief symptoms, and trait compassion. Furthermore, empathic and emotion processes uniquely mediated each of the DT and compassion connections. We discuss our results in terms of the callousness theory of DT and narcissism's positive correlation with compassion and empathy. © 2017 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction Researchers have shown great interest in socially aversive personality traits in nonclinical samples over the last decade. Machiavellianism, psychopathy, and narcissism, collectively known as the Dark Triad (DT), have proven to be more than just cardinal descriptions of cartoon villains, famous criminals, and maniacal leaders (Paulhus & Williams, 2002). Rather, studies of this constellation of traits have deepened our understanding of the darker side of personality and how it is expressed in average people (Paulhus, 2014). For instance, DT traits have been shown to predict a wide range of meaningful outcomes from mating behavior and academic cheating to prejudice and aggressive tendencies (Furnham, Richards, & Paulhus, 2013). Within this growing literature, one line of inquiry that warrants exploration is the link between the DT and compassion. Although many investigations have examined the relations of the DT with trait empathy, research has not explicitly studied compassion, which is surprising given that callousness in response to other individuals' needs is believed to be a unifying feature of the DT (Paulhus, 2014). The goal of the current study was to fill the void in the literature by examining compassion as a reaction to observed suffering. Compassion is a unique emotional response to someone's suffering that is characterized by both the feelings of sorrow and concern for the sufferer and a strong desire to alleviate their suffering (Goetz, Keltner, & Simon-Thomas, 2010). Although compassion is distinct from, but highly influenced by empathic processes, it has been shown ⁎ Corresponding author at: Department of Psychology, Christopher Newport University, 1 Avenue of the Arts, Newport News, VA 23606, United States. E-mail address: sherman.lee@cnu.edu (S.A. Lee). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.05.010 0191-8869/© 2017 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. to be the primary emotional driver of altruistic action (Lim & DeSteno, 2016). As the key to prosocial behavior, compassion has been central to the teachings of major religious traditions and of keen interest to scientists investigating the origins of altruism and violence (Lama & Ekman, 2008). Common conclusions about this emotion are that people vary to the degree they experience compassion when they encounter suffering and these differences are attributed to a variety of personlevel factors. For instance, social class (Steller, Manzo, Kraus, & Keltner, 2012), dispositional empathy (Masten, Morelli, & Eisenberger, 2011), and trait compassion (Lim & DeSteno, 2016) have all been found to influence compassion. Although the DT traits have not been explicitly linked to compassion, the literature demonstrates that personality traits impact this prosocial emotion. Despite the lack of empirical work relating the DT traits to compassion, researchers have shown a developing interest in the connections with trait empathy that provide insights into this proposed relationship. The literature has shown many examples where trait empathy is inversely associated with psychopathy (Giammarco & Vernon, 2014; Jonason & Krause, 2013; Jonason & Kroll, 2015), Machiavellianism (Giammarco & Vernon, 2014; Jonason & Krause, 2013; Jonason & Kroll, 2015; Wai & Tiliopoulos, 2012), and narcissism (Delič, Novak, Kovačič, & Avsec, 2011; Giammarco & Vernon, 2014). These findings reinforce the negative reputation of the DT, and they support a basic theoretical proposal that a lack of empathy is an underlying element that binds these traits together (Paulhus, 2014). However, the link between the DT and empathy is not straightforward in the case of narcissism. Although narcissism has shown negative correlations with trait empathy, which is consistent with the other DT traits, many studies have reported positive correlations between these two constructs (Jonason & Krause, 2013; Jonason & Kroll, 2015; Vonk, S.A. Lee, J.A. Gibbons / Personality and Individual Differences 116 (2017) 336–342 Zeigler-Hill, Mayhew, & Mercer, 2013; Wai & Tiliopoulos, 2012). The reason for this inconsistency continues to be unknown, but some viable theories explaining the positive association between narcissism and empathy have been proposed. For instance, researchers have suggested that the high empathy exhibited by some narcissists actually reflects a bias in their reporting of emotions (Wai & Tiliopoulos, 2012). Despite the fact that many narcissists are no more gifted than others at reading others' emotions, narcissists still have a tendency to rate themselves higher in emotional competence than their counterparts (Ames & Kammrath, 2004; Petrides, Vernon, Schermer, & Veselka, 2011). This propensity to exaggerate empathic ability could reflect both the narcissists' unrealistic sense of superiority (Wai & Tiliopoulos, 2012) as well as their high emotional expressiveness (Lyons & Brockman, 2017). On the other hand, other researchers have suggested that some narcissists may actually possess empathic tendencies. Vonk et al. (2013), for example, argue that some narcissists may rely on empathy to maintain their social bonds and their fragile self-worth. Being empathic in this instrumental sense can help narcissists take advantage of others in order to fulfill their interpersonally based needs (Jonason & Kroll, 2015). Taken together, the literature demonstrates that the DT traits are generally inversely associated with trait empathy, except in the case of narcissism where the findings are mixed. The DT literature has also focused on trait empathy and not on compassion as a feeling state. Therefore, the current study sought to address this gap in the literature by examining the predictive relation between the DT traits and state compassion using a sample of college students. We chose film methodology in the current study because it is a highly effective, reliable, and ecologically valid means for eliciting strong emotional responses in a laboratory setting (Rottenberg, Ray, & Gross, 2007). Given the trends found in previous research, we made the following predictions. First, we expected Machiavellianism and psychopathy to be negative predictors of compassion because these traits tend to be associated with low levels of dispositional empathy. Because empathy and compassion are closely related emotions, we believe that this similarity will also extend to the results of this study. Second, we expected narcissism to be a positive predictor of compassion because narcissists tend to be biased in their reporting of emotions. Moreover, because compassion is a moral emotion that was measured using self-report ratings, we believed that the narcissists would use that opportunity to express their emotions and self-righteous superiority over others. We statistically tested these predictions using a hierarchical multiple regression analysis. Because variables such as demographics, trait compassion, neuroticism, grief symptoms from an important loss, and 337 cohort size may confound the results of the study, we used the variables that were correlated with state compassion as statistical controls. We also examined the mediating effects of emotion and empathic processes reported during the film study in order to provide explanatory accounts for the specific links found between the DT traits and state compassion. In particular, changes in sadness and anxiety states were evaluated because they reflect the basic emotions that are central to the subjective experience of compassion (Goetz et al., 2010). Emotional empathy (i.e., feeling others' emotions) and perspective taking (i.e., understanding how others' may feel) were also evaluated because they represent the two basic facets of the empathy construct that are often implicated in the initiation of compassion (Lama & Ekman, 2008). Finally, a series of psychometric analyses were also conducted to ensure that state compassion, as it is the central variable of the current study, was reliably and validly measured. 2. Method 2.1. Participants and procedure Data from 156 college students (M age = 19.15) were used for this study. Most of the participants were White (n = 120), women (n = 128), and of Christian faith (n = 115). Nine participants were excluded from the analyses for not following protocols. The study took place in an auditorium style classroom using a small group format (Mgroup = 13.38), consistent with previous film studies (Gross & Levenson, 1995). After obtaining consent, participants completed a series of pre-film measures. Next, participants watched three film clips, edited and validated for affective science research (Gross & Levenson, 1995; Rottenberg et al., 2007; Samson, Kreibig, Soderstrom, Wade, & Gross, 2016), which were each followed by post-film measures. Films #1 (neutral) and #3 (neutral) were uneventful scenes of people in public places that were used as baselines for calculating changes in sadness and anxiety states (Rottenberg et al., 2007). Film #2 (death) is a scene from a 1979 movie, The Champ, which shows an emotional young boy reacting to his father dying. This death scene has been shown to reliably elicit sad emotional responses in college students (Gross & Levenson, 1995). 2.2. Measures 2.2.1. Pre-film measures The Dark Triad traits were assessed using Jonason and Webster's (2010) 12-item measure (αglobal = 0.84; αnarcissism = 0.84; Table 1 Factor loadings and descriptive statistics of the state empathy and state compassion items. # Item F1 F2 F3 M SD 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. I put myself in the young boy's place. I felt as if I was the young boy in the film clip. I imagined myself as the young boy. I experienced what the young boy was experiencing. I found it difficult to see the young boy's point of view.a It was easy for me to understand how the young boy was feeling. I was able to relate to how the young boy was feeling. It was easy to take on the young boy's perspective. I felt sorry for the young boy. I felt concerned for the young boy. It broke my heart to see the young boy in that condition. I did not feel very much sorrow or concern for the young boy.a I felt an overwhelming desire to comfort the young boy. I felt a strong desire to end the young boy's emotional pain. I wished that I could help the young boy feel better. I really wanted to soothe the young boy. 0.251 0.194 0.254 0.247 0.120 0.069 0.207 0.265 0.622 0.631 0.680 0.523 0.838 0.814 0.881 0.877 0.785 0.874 0.827 0.483 0.060 0.145 0.221 0.260 0.127 0.121 0.216 0.090 0.223 0.213 0.217 0.283 0.292 0.110 0.172 0.347 0.414 0.877 0.690 0.756 0.352 0.336 0.276 0.125 0.060 0.131 0.134 0.120 1.93 1.26 1.54 1.41 0.43 2.68 2.12 2.56 3.58 3.26 3.18 0.35 2.57 2.47 2.88 2.74 1.34 1.34 1.42 1.31 0.82 1.21 1.33 1.25 0.84 1.07 1.18 0.82 1.34 1.27 1.19 1.31 Note. Item number = #; factors for pattern/structure coefficient loadings (F1, F2, F3); State emotional empathy (items 1–4; F2); state perspective taking (items 5–8; F3); State compassion (items 9–16; F1); M = mean; SD = standard deviation. Italics indicates the target of the emotion. a Reverse score item. 338 S.A. Lee, J.A. Gibbons / Personality and Individual Differences 116 (2017) 336–342 Table 2 Zero-order correlations among main study variables. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. DT PSY NAR MAC N TC GRF AX-REAC AX-RECO SD-REAC SD-RECO PT EE COMP M SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 2.21 1.65 2.86 2.12 2.74 3.97 0.84 1.15 −0.76 1.82 −1.79 2.73 1.54 3.04 0.63 0.71 0.89 0.86 1.02 0.77 0.62 0.96 0.93 1.04 1.05 0.94 1.16 0.93 – 0.68⁎⁎ 0.77⁎⁎ 0.89⁎⁎ 0.26⁎⁎ −0.23⁎⁎ −0.05 −0.08 0.13 −0.05 0.06 −0.14 −0.02 −0.13 – 0.21⁎⁎ 0.47⁎⁎ 0.00 −0.53⁎⁎ −0.13 −0.19⁎ 0.18⁎ −0.19⁎ 0.22⁎⁎ −0.33⁎⁎ −0.23⁎⁎ −0.47⁎⁎ – 0.49⁎⁎ 0.35⁎⁎ 0.06 0.04 0.07 −0.02 0.14 −0.14 0.05 0.20⁎ 0.19⁎ – 0.20⁎ −0.14 −0.03 −0.10 0.15 −0.10 0.09 −0.08 −0.07 −0.10 – 0.14 0.20⁎ −0.03 0.07 0.08 −0.08 0.02 0.08 0.14 – 0.26⁎⁎ 0.26⁎⁎ −0.13 0.31⁎⁎ −0.31⁎⁎ 0.43⁎⁎ 0.41⁎⁎ 0.65⁎⁎ – 0.17⁎ −0.13 0.30⁎⁎ −0.30⁎⁎ 0.34⁎⁎ 0.37⁎⁎ 0.26⁎⁎ – −0.64⁎⁎ 0.70⁎⁎ −0.70⁎⁎ 0.17⁎ 0.41⁎⁎ 0.45⁎⁎ – −0.48⁎⁎ 0.55⁎⁎ −0.16⁎ −0.32⁎⁎ −0.26⁎⁎ – −0.93⁎⁎ 0.28⁎⁎ 0.46⁎⁎ 0.62⁎⁎ – −0.27⁎⁎ −0.45⁎⁎ −0.58⁎⁎ – 0.49⁎⁎ 0.44⁎⁎ – 0.52⁎⁎ Note. DT = Dark Triad composite; PSY = psychopathy; NAR = narcissism; MAC = Machiavellianism; N = neuroticism; TC = trait compassion; GRF = grief symptoms; AX-REAC = anxiety reactivity; AX-RECO = anxiety recovery; SD-REAC = sadness reactivity; SD-RECO = sadness recovery; PT = state perspective taking; EE = state emotional empathy; COMP = state compassion. ⁎ p b 0.05. ⁎⁎ p b 0.01. αMachiavellianism = 0.77; αpsychopathy = 0.75). Trait compassion was measured using Hwang, Plante, and Lackey's (2008) 5-item measure (e.g., “I tend to feel compassion for people, even though I do not know them.”; α = 0.89). Neuroticism was measured with Gosling, Rentfrow, and Swann's (2003) 2-item measure (e.g., “I see myself as anxious, easily upset.”; α = 0.75). Grief symptoms experienced from an important loss were assessed using Lee's (2015) 16-item measure (e.g., “Preoccupied with the deceased.”; α = 0.91). All these measures utilized an agreement scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree), excluding the assessment of grief, which was based on a frequency scale (0 = not at all; 4 = nearly every day). Except for the DT traits, all these measures and demographic variables were examined for their confounding influences. 2.2.2. Post-film measures After viewing each of the three film clips, participants rated how they felt, with an intensity scale (0 = not at all; 1 = slightly; 2 = moderately; 3 = quite a bit; 4 = extremely), about a series of emotion states. Sadness was assessed using three adjectives (i.e., upset, sad, and depressed) from Lee, Roberts, and Gibbons' (2013) grief measure (αf1 = 0.72; αf2 = 0.84; αf3 = 0.79). Anxiety was assessed using three adjectives (i.e., calm, tense, and worried) from Marteau and Bekker's (1992) anxiety measure (αf1 = 0.62; αf2 = 0.76; αf3 = 0.69). Adjective ratings were averaged together to form composite scores for each respective emotion. In addition, a series of repeated-measures ANOVAs demonstrated that the sadness and anxiety scores were expectedly highest following film #2 (death) relative to film #1 (neutral) and film #3 (neutral). To compute two parameters of change in sadness and anxiety states (i.e., reactivity and recovery), the composite scores were then converted into simple change scores. Specifically, reactivity refers to the increase in feeling intensity experienced after watching the death scene. This index was calculated as the difference between feelings assessed after film #1 (neutral) and the feelings assessed after film #2 (death). Recovery refers to how much residual feelings remained after watching the neutral film clip that followed the death scene. Recovery was calculated as the difference between feelings assessed after film #3 (neutral) and the feelings assessed after film #2 (death). Because these emotion processes captured the changes in feeling states experienced during the film study, they were used to examine the validity of the state compassion measure and for mediation analyses. State compassion and two dimensions of empathy (i.e., perspective taking and emotional empathy) were assessed after viewing film #2 (death) using the same intensity scaling as the emotion processes. Perspective taking (α = 0.82) and emotional empathy (α = 0.88) were assessed using Lee's (2009) 4-item measures of state empathy, while an 8-item measure of state compassion was developed from Lee's (2009) state sympathy scale. It is important to note that state compassion and empathy were only evaluated after film #2 because these emotions are directed toward the grieving child. Because the neutral film clips (#1 and #3) have no particular object to feel compassion or empathy toward, those emotions were not measured for those films. Fig. 1. Mediating effect of emotional empathy on the association between narcissism and state compassion. Note. Two-sided bias-corrected bootstrap procedure (95% confidence intervals; 2000 samples). Above values reflect standardized regression coefficients. * p b 0.05. *** p b 0.001. S.A. Lee, J.A. Gibbons / Personality and Individual Differences 116 (2017) 336–342 339 Fig. 2. Mediating effect of perspective taking on the association between psychopathy and state compassion. Note. Two-sided bias-corrected bootstrap procedure (95% confidence intervals; 2000 samples). Above values reflect standardized regression coefficients. *** p b 0.001. Like sadness and anxiety, the measures of perspective taking and emotional empathy were also used for mediation analyses, while the measure of state compassion was used as the criterion variable for the study. At the end of the study, participants also completed a form that asked them if they wanted to volunteer their time to help bereaved individuals (22.4% = yes) and the number of hours per week they were available (Mhours = 6.94). This assessment of volunteer intention was used to examine the validity of the state compassion measure. 3. Results 3.1. Psychometric analyses of the state compassion measure A series of analyses were performed on the measure of state compassion to ensure that the construct was appropriately assessed (see Tables 1 and 2). First, the results of a principal axis factor analysis (varimax rotation) determined that the state compassion items loaded strongly on their own factor (N 0.50 loadings; convergent validity) and not with the perspective taking and emotional empathy factors (b 0.35 cross-loadings; discriminant validity). Second, correlations between state compassion and trait compassion (r = 0.65), intention to volunteer (r = 0.23), and number of hours intended to volunteer (r = 0.17) supported the measure's construct validity by being consistent with previous research (Lim & DeSteno, 2016). Last, state compassion was associated with increased sadness (r = 0.62) and anxiety (r = 0.45) immediately after viewing the death scene and then prolonged feelings of sadness (r = −0.58) and anxiety (r = −0.26) minutes later. These correlations further support the validity of the state compassion measure by following a pattern associated with the experience of compassion (Goetz et al., 2010). Collectively, these results demonstrate that the state compassion measure exhibits solid psychometric properties. 3.2. Associations between the Dark Triad and state compassion Bivariate correlations were run to identify the DT traits that were associated with state compassion and the variables that should be used as control variables in the regression model. The results showed that psychopathy (r = −0.47) and narcissism (r = 0.19) were the only DT traits correlated with state compassion. Because women (r = 0.40), Whites (r = 0.25), Christians (r = 0.17), grief (r = 0.26), and trait compassion (r = 0.65) were also correlated with state compassion, they were subsequently used as control variables. A hierarchical multiple regression analysis was performed to clarify the predictive relation between the relevant DT traits and state compassion. Preliminary analyses revealed no problems associated with singularity, multicollinearity, dependence of errors, normality, linearity, homoscedasticity of residuals, or outliers. The analysis was performed in two steps. In the first step, when the control variables were entered into the model, women (β = 0.16, p b 0.05), Whites (β = 0.18, p b 0.01), and trait compassion (β = 0.54, p b 0.001) were predictors, whereas Christians (β = 0.04, p = 0.64, ns) and grief (β = 0.08, p = 0.22, ns) were not, adjusted R2 = 0.47, F(5, 150) = 28.27, p b 0.001. In the second step, when the DT traits were entered into the model, the control variables of Whites (β = 0.16, p b 0.01) and trait compassion (β = 0.44, p b 0.001) continued to be predictors, while Christians (β = 0.02, p = 0.71, ns), grief (β = 0.08, p = 0.20, ns), and women (β = 0.12, p = 0.05, ns) were not. The DT traits of narcissism (β = 0.17, p b 0.05) and psychopathy (β = −0.21, p b 0.01) were also predictors, whereas Fig. 3. Mediating effect of emotional empathy on the association between psychopathy and state compassion. Note. Two-sided bias-corrected bootstrap procedure (95% confidence intervals; 2000 samples). Above values reflect standardized regression coefficients. ** p b 0.01. *** p b 0.001. 340 S.A. Lee, J.A. Gibbons / Personality and Individual Differences 116 (2017) 336–342 Fig. 4. Mediating effect of sadness reactivity on the association between psychopathy and state compassion. Note. Two-sided bias-corrected bootstrap procedure (95% confidence intervals; 2000 samples). Above values reflect standardized regression coefficients. * p b 0.05. *** p b 0.001. Machiavellianism was not (β = 0.002, p = 0.98, ns), adjusted R2 = 0.50, F(8, 147) = 20.42, p b 0.001. These results not only demonstrated DT traits unique predictive relationship with state compassion, but that these traits also accounted for an additional 3% of variance above and beyond control variables, F(8, 147) = 20.42, p b 0.001. 3.3. Empathy and emotional processes as mediators A series of mediation analyses were conducted to examine the separate influences of empathy (i.e., perspective taking and emotional empathy) and emotion processes (i.e., reactivity and recovery of anxiety and sadness states) on the relation between the relevant DT traits (i.e., narcissism and psychopathy) and state compassion (see Figs. 1–7). We focused our analyses on variables that were interrelated and tested mediators one at a time to determine independent effects (Kenny, 2016). The first model tested emotional empathy's mediating influence on the relationship between narcissism and state compassion. The results showed that emotional empathy completely mediated the narcissismcompassion link (β from 0.19 to 0.08). The second set of models tested the independent mediating influences of empathy (i.e., perspective taking and emotional empathy) and emotion processes (i.e., sadness and anxiety) on the relationship between psychopathy and state compassion. The results showed that perspective taking (β from − 0.46 to −0.36), emotional empathy (β from −0.46 to −0.37), sadness reactivity (β from − 0.46 to − 0.36), sadness recovery (β from − 0.46 to −0.35), anxiety reactivity (β from −0.46 to −0.39), and anxiety recovery (β from −0.46 to −0.43), each partially mediated the psychopathycompassion link. Overall, these findings indicate that empathic and emotional processes have mediating effects on the relationship between the DT traits and state compassion. 4. Discussion The purpose of the current study was to examine the predictive relation between the DT traits and state compassion using validated film methodology. Although previous DT studies have explored links with trait empathy, no study to date has extended this line of research to the construct of compassion. Unlike the empathy research, which usually displays the similarities between the DT traits, the results of this study highlighted their distinct qualities as each of the DT traits exhibited unique relations with state compassion. These differences were found in both the bivariate associations between the DT and compassion, as well as their mediating pathways through empathy and emotional processes. Psychopathy exhibited the strongest and most conceptually consistent patterns among the DT. Consistent with our hypothesis, psychopathy was a negative predictor of state compassion. In fact, psychopathy was such a robust predictor that it uniquely explained compassion scores over and above demographics, grief symptoms, and trait compassion. This result was not surprising given that psychopathy has also been associated with many anti-compassionate characteristics, such as being emotionally abusive (Carton & Egan, 2017) and exhibiting low levels of empathy (Jonason & Kroll, 2015) and care for others' plights (Blair, 1999). Further analyses revealed that the psychopathy-compassion connection was mediated, in part, by empathic and emotional processes. In other words, during the viewing of the sad film clip, those individuals demonstrating psychopathic propensities tended not to empathically Fig. 5. Mediating effect of sadness recovery on the association between psychopathy and state compassion. Note. Two-sided bias-corrected bootstrap procedure (95% confidence intervals; 2000 samples). Above values reflect standardized regression coefficients. ** p b 0.01. *** p b 0.001. S.A. Lee, J.A. Gibbons / Personality and Individual Differences 116 (2017) 336–342 341 Fig. 6. Mediating effect of anxiety reactivity on the association between psychopathy and state compassion. Note. Two-sided bias-corrected bootstrap procedure (95% confidence intervals; 2000 samples). Above values reflect standardized regression coefficients. * p b 0.05. *** p b 0.001. see the child's point of view (perspective taking) nor did they deeply feel the child's inner experiences (emotional empathy). Although many participants naturally felt sadness and anxiety after watching the death scene (emotional reactivity) and held on to these feelings minutes later (prolonged emotion recovery), individuals high in psychopathy generally did not experience this pattern. Rather, they appeared remarkably unmoved and unaffected by feelings of sorrow and concern. This coldhearted response to suffering corroborates the central features of psychopathy as well as emphasizing the importance of callousness in conceptualizing the DT (Paulhus, 2014). The next notable finding was the positive association between narcissism and state compassion. Like psychopathy, narcissism explained unique variance in state compassion beyond the effects of other relevant variables. Furthermore, the mediation analysis revealed that the compassion that the narcissists experienced during the sad film was fully explained by their emotional empathy for the distraught child. These findings not only confirmed our prediction, but they were also in keeping with our proposal that the narcissists will report relatively high compassion ratings because of their emotionally expressive proclivities (Lyons & Brockman, 2017) and need to display their superiority (Wai & Tiliopoulos, 2012). Although the results with narcissism are in line with our theoretical proposals, they do not rule out the possibility that the child in the film clip actually empathically moved some narcissists. Vonk et al. (2013) reasoned that some narcissists, such as ones displaying pathological grandiosity, demonstrate empathic tendencies to maintain their self-esteem. Because narcissists rely on interpersonal feedback to bolster their fragile self-image, some of them may develop empathic habits to maintain the social connections upon which they are psychologically reliant. In support of this perspective, researchers have found that some narcissists show heightened empathic characteristics, as measured by fantasy empathy (Vonk et al., 2013), emotional intelligence (Petrides et al., 2011) and emotion recognition ability (Konrath, Corneille, Bushman, & Luminet, 2014). Therefore, the results of the current study may have showcased this phenomenon as well. The lack of correlation between Machiavellianism and state compassion was not expected. Much like psychopathy, previous research has typically shown that Machiavellianism is negatively correlated with trait empathy (e.g., Jonason & Kroll, 2015). However, the magnitude of the relation is often relatively small. Although we are not certain about the reason that this trend did not persist in the current study, we suspect that the trait empathy scales were sensitive enough to tap into the negative views held by Machiavellians (Jones & Paulhus, 2009), whereas the state compassion measure was not. As the selfreporting of compassion in the current study did not hold any obvious strategic advantages, this aspect of Machiavellianism (Jones & Paulhus, 2009) was also not elicited. Therefore, the attitudinal and strategic dimensions that were not present in the measurement of state compassion may explain these null findings. Another null finding worth discussing was the lack of correlation between the composite DT and state compassion. At first glance, this nonsignificant connection seems to challenge the basic notion that callousness lies at the heart of the DT. However, the results also demonstrated that the composite DT was inversely associated with trait level compassion, in support of the callousness proposal. These patterns seem to reflect the findings of past personality psychologists; broad personality traits are limited in their ability to predict specific behaviors (Epstein, 1979). Researchers have found that broad level dispositions are better at predicting broad behaviors that are aggregated together, rather than specific ones. Due to the similar findings in other DT research Fig. 7. Mediating effect of anxiety recovery on the association between psychopathy and state compassion. Note. Two-sided bias-corrected bootstrap procedure (95% confidence intervals; 2000 samples). Above values reflect standardized regression coefficients. * p b 0.05. *** p b 0.001. 342 S.A. Lee, J.A. Gibbons / Personality and Individual Differences 116 (2017) 336–342 (e.g., Jonason, Kavanagh, Webster, & Fitzgerald, 2011), we believe that these measurement level effects applied to this study as well. The results of the current study must be qualified by some limitations. First, we only evaluated self-reported feelings, which is just one aspect of the emotion system. Although feelings serve an important function of integrating relevant information and guiding responses (Frijda, Manstead, & Fischer, 2004), future research would benefit from including other domains, such as behavioral and physiological, for a more comprehensive perspective on emotion. Second, we used simple change scores to capture changes in emotions. Although this approach is commonly used in emotion research (e.g., Hemenover, 2003), it does not adjust for error. Replication of this study using latent variable modeling with a large sample could provide more reliable estimates of change than the approach used here. The final limitation concerns our use of a homogenous sample composed primarily of White, emerging adult women. Although our sample is demographically similar to the ones evaluated at other universities, replication of the current research with non-student groups could extend the generalizability of the results in the current study. Acknowledgments We would like to thank Win Kent, Ben Pearce, Summer Bledsoe and the rest of the EP lab for their assistance and support of this project. This article is dedicated to the loving memory of Mr. Tigger Brambley. References Ames, D. R., & Kammrath, L. K. (2004). Mind-reading and metacognition: Narcissism, not actual competence, predicts self-estimated ability. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 28, 187–209. Blair, R. J. R. (1999). Responsiveness to distress cues in the child with psychopathic tendencies. Personality and Individual Differences, 27, 135–145. Carton, H., & Egan, V. (2017). The dark triad and intimate partner violence. Personality and Individual Differences, 105, 84–88. Delič, L., Novak, P., Kovačič, J., & Avsec, A. (2011). Self-reported emotional and social intelligence and empathy as distinctive predictors of narcissism. Psychological Topics, 20, 477–488. Epstein, S. (1979). The stability of behavior: I. On predicting most of the people much of the time. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 1097–1126. Frijda, N. H., Manstead, A. S. R., & Fischer, A. H. (2004). Epilogue: Feelings and emotions – Where do we stand? In A. S. R. Manstead, N. H. Frijda, & A. H. Fischer (Eds.), Feelings and emotions: The Amsterdam symposium (pp. 455–467). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Furnham, A., Richards, S. C., & Paulhus, D. L. (2013). The dark triad of personality: A 10 year review. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 7, 199–216. Giammarco, E. A., & Vernon, P. A. (2014). Vengeance and the dark triad: The role of empathy and perspective taking in trait forgiveness. Personality and Individual Differences, 67, 23–29. Goetz, J. L., Keltner, D., & Simon-Thomas, E. (2010). Compassion: An evolutionary analysis and empirical review. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 351–374. Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., & Swann, W. B. (2003). A very brief measure of the Big Five personality domains. Journal of Research in Personality, 37, 504–528. Gross, J. J., & Levenson, R. W. (1995). Emotion elicitation using films. Cognition and Emotion, 9, 87–108. Hemenover, S. H. (2003). Individual differences in rate of affect change: Studies in affective chronometry. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 121–131. Hwang, J. Y., Plante, T., & Lackey, K. (2008). The development of the Santa Clara brief compassion scale: An abbreviation of Sprecher and Fehr's compassionate love scale. Pastoral Psychology, 56, 421–428. Jonason, P. K., Kavanagh, P. S., Webster, G. D., & Fitzgerald, D. (2011). Comparing the measured and latent dark triad: Are three measures better than one? Journal of Methods and Measurement in the Social Sciences, 2, 28–44. Jonason, P. K., & Krause, L. (2013). The emotional deficits associated with the dark triad traits: Cognitive empathy, affective empathy, and alexithymia. Personality and Individual Differences, 55, 532–537. Jonason, P. K., & Kroll, C. K. (2015). A multidimensional view of the relationship between empathy and the dark triad. Journal of Individual Differences, 36, 150–156. Jonason, P. K., & Webster, G. D. (2010). The dirty dozen. A concise measure of the dark triad. Psychological Assessment, 22, 420–432. Jones, D. N., & Paulhus, D. L. (2009). Machiavellianism. In M. R. Leary, & R. H. Hoyle (Eds.), Handbook of individual differences in social behavior (pp. 93–108). New York: Guilford. Kenny, D. A. (2016, September 28). Mediation. (Retrieved from http://davidakenny.net/ cm/mediate.htm). Konrath, S., Corneille, O., Bushman, B. J., & Luminet, O. (2014). The relationship between narcissistic exploitativeness, dispositional empathy, and emotion recognition abilities. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 38, 129–143. Lama, D., & Ekman, P. (2008). Emotional awareness: A conversation between the Dalai Lama and Paul Ekman. New York, NY: Holt. Lee, S. A. (2009). Measuring individual differences in trait sympathy: Instrument construction and validation. Journal of Personality Assessment, 91, 568–583. Lee, S. A. (2015). The persistent complex bereavement inventory: A measure based on the DSM-5. Death Studies, 39, 399–410. Lee, S. A., Roberts, L. B., & Gibbons, J. A. (2013). When religion makes grief worse: Negative religious coping as associated with maladaptive emotional responding patterns. Mental Health, Religion and Culture, 16, 291–305. Lim, D., & DeSteno, D. (2016). Suffering and compassion: The links among adverse life experiences, empathy, compassion, and prosocial behavior. Emotion, 16, 175–182. Lyons, M., & Brockman, C. (2017). The dark triad, emotional expressivity and appropriateness of emotional response: Fear and sadness when one should be happy? Personality and Individual Differences, 104, 466–469. Marteau, T. M., & Bekker, H. (1992). The development of a six-item short-form of the state scale of the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 31, 301–306. Masten, C. L., Morelli, S. A., & Eisenberger, N. I. (2011). An fMRI investigation of empathy for 'social pain' and subsequent prosocial behavior. NeuroImage, 55, 381–388. Paulhus, D. L. (2014). Toward a taxonomy of dark personalities. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23, 421–426. Paulhus, D. L., & Williams, K. M. (2002). The dark triad of personality: Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Journal of Research in Personality, 36, 556–563. Petrides, K. V., Vernon, P. A., Schermer, J. A., & Veselka, L. (2011). Trait emotional intelligence and the dark triad traits of personality. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 14(1), 35–41. Rottenberg, J., Ray, R. D., & Gross, J. J. (2007). Emotion elicitation using films. In J. A. Coan, & J. J. B. Allen (Eds.), Handbook of emotion elicitation and assessment (pp. 9–28) (1st ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. Samson, A. C., Kreibig, S. D., Soderstrom, B., Wade, A. A., & Gross, J. J. (2016). Eliciting positive, negative and mixed emotional states: A film library for affective scientists. Cognition and Emotion, 30, 827–856. Steller, J. E., Manzo, V. M., Kraus, M. W., & Keltner, D. (2012). Class and compassion: Socioeconomic factors predict responses to suffering. Emotion, 12, 449–459. Vonk, J., Zeigler-Hill, V., Mayhew, P., & Mercer, S. (2013). Mirror mirror on the wall: Which form of narcissist knows self and others best of all? Personality and Individual Differences, 54, 396–401. Wai, M., & Tiliopoulos, N. (2012). The affective and cognitive empathic nature of the dark triad of personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 52, 794–799.