A vote for the President The role of Spitzenkandidaten in the 2014 European Parliament elections

Anuncio

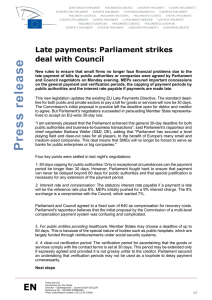

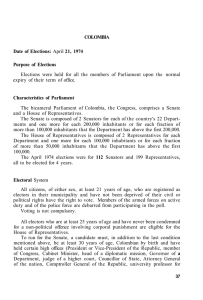

Journal of European Public Policy ISSN: 1350-1763 (Print) 1466-4429 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjpp20 A vote for the President? The role of Spitzenkandidaten in the 2014 European Parliament elections Sara B. Hobolt To cite this article: Sara B. Hobolt (2014) A vote for the President? The role of Spitzenkandidaten in the 2014 European Parliament elections, Journal of European Public Policy, 21:10, 1528-1540, DOI: 10.1080/13501763.2014.941148 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2014.941148 Published online: 17 Jul 2014. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 7612 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 65 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rjpp20 Journal of European Public Policy, 2014 Vol. 21, No. 10, 1528 –1540, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2014.941148 A vote for the President? The role of Spitzenkandidaten in the 2014 European Parliament elections Sara B. Hobolt ABSTRACT The European Parliament promised voters that the 2014 elections would be different. According to its interpretation of the Lisbon Treaty, a vote in these European elections would also be a vote for the President of the Europe’s executive, the Commission. To reinforce this link between the European elections and the Commission President, the major political groups each nominated a lead candidate, Spitzenkandidat, for the post. This article examines how this innovation affected the 2014 elections. It concludes that the presidential candidates did not play a major role in the election campaigns, except in a handful of countries, and thus had a limited impact on voter participation and vote choices. However, the European Parliament was very successful in imposing its interpretation of the new modified procedure for electing the Commission President, not shared by all national governments, and this will have important implications for the inter-institutional dynamics in the Union and the future of European democracy. KEY WORDS Commission Parliament; Spitzenkandidaten President; democracy; elections; European INTRODUCTION ‘This time it’s different,’ proclaimed billboards on the European Parliament in the weeks leading up to the 2014 European Parliament elections. One aspect of these elections that was different from the previous elections was that Europeanlevel parties for the first time had proposed rival candidates, the so-called Spitzenkandidaten (lead candidates), for the most powerful executive office in the European Union (EU) – the Commission President – prior to the elections. This change was rooted in a modification of the procedure for choosing the Commission President. Whereas the President was previously chosen by a consensus of European leaders in the European Council which was approved by the European Parliament, the Lisbon Treaty stipulates that the European Council shall nominate a candidate ‘taking into account the elections to the European Parliament’, by qualified majority, and the parliament in turn must ‘elect’ the nominee with an absolute majority (Article 17 of the Treaty on European Union [TEU]). # 2014 Taylor & Francis S.B. Hobolt: The role of Spitzenkandidaten in the 2014 European Parliament elections 1529 In conjunction with the introduction of Spitzenkandidaten by Euro-parties, this modified procedure ostensibly makes European elections similar to parliamentary elections in national democracies, where voters cast for a ballot for a party (or candidate) in the knowledge that this is also a vote for a specific prime ministerial candidate and government. A vote for the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) in Germany or the Conservatives in Britain is not just a vote for parliamentary candidates, but also a vote for Chancellor Merkel and Prime Minister Cameron, and an endorsement of their governments. Thus, in theory at least, the 2014 European Parliament elections allowed voters to give a mandate to specific political platform for the EU’s executive body, the Commission. In response to decades of falling turnout and declining trust in EU institutions, the hope was that the introduction of Spitzenkandidaten would strengthen the European element in the campaigns, personalize the distant Brussels bureaucracy, and thereby increase interest and participation in European democracy. While national governments were for the most part mute on the issue of how the next Commission President would be elected, the European Parliament boldly promised voters that ‘after the next elections it is your parliament who will elect the head of Europe’s executive, based on your wishes, as expressed in these elections. This time it’s different. Together we now have more power to make a difference’ (European Parliament 2013). Was it different this time? This article examines the impact of the Spitzenkandidaten on the 2014 European Parliament elections. It discusses how the constitutional innovation of the procedure for electing the President originates in both the normative debate on how to improve the democratic legitimacy of the European Union and in the inter-institutional wrangling between the European Parliament and the Council. Thereafter, it examines the variation in the impact of the lead candidates in the electoral campaigns across Europe. The most heated debate on the Spitzenkandidaten occurred after the elections, as the battle on who will be the next Commission President commenced. I argue that while the Spitzenkandidaten played a limited role in the determining the composition of the European Parliament, this constitutional experiment nonetheless has important implications for inter-institutional dynamics in the Union, and in the long term it may even reshape the nature of European elections. THE ELECTORAL DISCONNECT IN THE EUROPEAN UNION When direct elections to the European Parliament were introduced in 1979, the hope was that this would enhance the democratic dimension of policy-making in the European Union, by creating a legislative chamber that was accountable to and representative of voters’ interests, thus legitimizing the exercise of power in the EU (Hobolt and Franklin 2011). Previously, the democratic legitimacy rested solely, in an intergovernmental manner, on the national governments in the Council. However, the pooling of sovereignty at the European level and the move away from unanimity in the Council (meaning that individual 1530 Journal of European Public Policy governments could be outvoted) put pressure on the EU to establish a ‘European’ electoral dimension, where voters could be directly represented at the European level, rather than only indirectly through their national governments. In response to these normative demands for a stronger European dimension of democratic legitimation in the EU, successive treaty changes have strengthened the legislative powers of the European Parliament, making it a genuine co-legislature with the Council (Hix et al. 2007; Rittberger 2005). The reforms introduced in the Maastricht Treaty (1993), and reinforced in the Amsterdam Treaty (1999), also strengthened the Parliament’s role in selecting the European Commission, the executive arm of the EU. As the only directly elected institution in the EU, the European Parliament skilfully used the normative arguments about the need for more democracy to bargain for more powers, and it was able to expand its competences incrementally in return for its consent to decisions and policies that the Council was eager to have (Hix et al. 2007; Rittberger 2005). Despite the increased powers of the European Parliament, the elections have not brought about the genuine electoral connection between voters and EU policy-making that was hoped for. Turnout to European Parliament elections declined in successive elections from 62 per cent in 1979 to only 43 per cent in 2009 and 2014, raising question about the democratic legitimacy of the EU (Franklin and Hobolt 2011). Moreover, it is well-established that European elections have largely failed in providing a strong democratic mandate for policy-making at the European elections, and parties and election campaigns have instead focused largely on domestic matters, at least until recently. These elections have therefore been referred to as ‘second-order national elections’ (Reif and Schmitt 1980; van der Eijk and Franklin 1996), where voters behave differently than in national elections. Studies have highlighted three broad trends of voting behaviour in European Parliament elections (e.g., Hix and Marsh 2007; Marsh 1998; van der Eijk and Franklin 1996). First, levels of turnout are lower than in national elections. Second, citizens favour smaller parties over larger ones compared to national elections. Third, parties in national governments do worse in European elections than in national elections. More recently, research has also shown that Eurosceptic parties perform better in European Parliament elections, even when taking into account party size (De Vries et al. 2011; Hix and Marsh 2011; Hobolt and Spoon 2012; Hobolt et al. 2009;). This second-order nature of European elections have been attributed to the fact that citizens generally have little knowledge of policies implemented or promised at the European level by parties, and parties themselves often use these elections as opportunities to test their standing with the public in terms of their domestic political agendas. The legislative process in the European Parliament operates very much like in any national legislature with members belonging to EU-level political groups – such as the centre-right European People’s Party (EPP) and the centre-left Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D) – that structure debate over and support for legislation S.B. Hobolt: The role of Spitzenkandidaten in the 2014 European Parliament elections 1531 and they decide vital political issues (Hix et al. 2006, 2007). However, despite the presence of traditional party politics at the European level, voters are generally unaware of this and Euro-parties have traditionally played a limited role in EP election campaigns. This is not least owing to the fact that, unlike national parliamentary systems, these elections have not been genuine contests between competing government alternatives and over incumbent performance records. While Euro-parties produce electoral manifestos, the extent to which the national parties use these manifestos in their own campaigning has traditionally been minimal. Instead, European election campaigns have tended to focus on domestic political matters and be dominated by national political actors. In between European elections, the European Parliament is largely ignored by national media (Norris 2000; Peter and de Vreese 2004). It is therefore unsurprising that citizens have limited knowledge of the workings of the European Parliament,1 and this has led scholars and politicians alike to suggest constitutional innovations that could remedy the growing democratic deficit in the European Union. A PARLIAMENTARY MODEL OF DEMOCRACY? CONSTITUTIONAL INNOVATION There is a long-standing debate in the academic literature on how to solve the so-called ‘democratic deficit’ in the European Union, and how to make the EU more legitimate in the eyes of citizens. A key controversy exists between those who argue that the EU should be legitimated through mechanisms of democratic input, such as mechanisms of accountability (e.g., Føllesdal and Hix 2006; Habermas 2012; Hix 2008) and those who argue that the EU should be legitimated through its performance, by providing solutions to common problems (e.g., Majone 1998, 2000; Scharpf 1999). For those who emphasize input legitimacy, elections to the European Parliament is the primary mechanism through which citizens can provide a democratic mandate and hold EU institutions to account. However, despite the formal powers of the European Parliament over the approval and dismissal of the European Commission established in previous treaty revisions, the link between the political majority in the Parliament and the policies of the Commission has remained tenuous. The lack of an open contest for the Commission Presidency, between candidates with competing policy agendas and different records, has made it near impossible for voters to identify which parties are responsible for the current policy outcomes and which parties offer an alternative (Hix 2008; Hix et al. 2007). Føllesdal and Hix (2006: 548) write: ‘as the EU is currently designed, there is no room to present a rival set of leadership candidates (a government “in waiting”) and a rival policy agenda’. Indeed, studies have shown that voters do not use European Parliament elections to reward or punish European politicians for past performance (Hobolt and Tilley 2014). Advocates of greater democratic accountability in the European Union have thus pushed for treaty changes that would make the EU more like a 1532 Journal of European Public Policy quasi-parliamentary system by enhancing the Parliament’s role in electing the EU’s executive. Prior to the Lisbon Treaty, the President of the European Commission was appointed by member states’ heads of state and government meeting in European Council meeting, before being approved by the European Parliament, but the Lisbon Treaty brought about an important change to the appointment process of the President of the European Commission. These changes emphasized that the European Council should ‘take into account the elections’ before nominating and that the European Parliament subsequently ‘elects’ the Council nominee. Taking into account the elections to the European Parliament and after having held the appropriate consultations, the European Council, acting by a qualified majority, shall propose to the European Parliament a candidate for President of the Commission. This candidate shall be elected by the European Parliament by a majority of its component members. If he does not obtain the required majority, the European Council, acting by a qualified majority, shall within one month propose a new candidate who shall be elected by the European Parliament following the same procedure. (Article 17(7) TEU; emphases added). The wording of the treaty is ambiguous when it comes to the powers of the European Parliament to impose its own candidate, however. The European Parliament seized upon the treaty change by deciding that the European political groups would nominate lead candidates, or Spitzenkandidaten, for the post of European Commission president. In a resolution agreed on 22 November 2012, the European Parliament urged the European political parties to nominate candidates for President of the Commission. This resolution further emphasized the increased role that the elections to the European Parliament play in electing the President of the Commission.2 Ostensibly, this was done in order to raise the stakes of the vote, personalize the electoral campaign, enhance the European dimension of the election campaign, and thus to attract more voters to the polls and create a clearer democratic mandate for the European Commission. The European Commission provided explicit support for the European Parliament’s move towards Spitzenkandidaten, arguing that this ‘would make concrete and visible the link between the individual vote of a citizen of the Union for a political party in the European elections and the candidate for President of the Commission supported by that party’ and thereby increase the legitimacy and accountability of the Commission, and more generally the democratic legitimacy of EU policy-making.3 The initiative was also quite popular with citizens: according to a Eurobarometer survey conducted in the autumn of 2013, 57 per cent of EU citizens were in favour of ‘European political parties to present their candidate for the post of European Commission President at the next European Parliament elections’, ranging from 43 per cent in the United Kingdom (UK) to over 70 per cent in Hungary and Sweden.4 The European Council and its President were more guarded in their praise of the Spitzenkandidaten innovation, and openly S.B. Hobolt: The role of Spitzenkandidaten in the 2014 European Parliament elections 1533 questioned whether one of these candidates would be nominated as next Commission President (see European Voice 2014). The hesitation on the part of national governments is not surprising, since the introduction of Spitzenkandidaten can be seen as a very clear attempt by the European Parliament to enhance its own influence on the selection of the Commission President. The Lisbon Treaty reserves the right to appoint the President of the European Commission to the European Council, and whereas the Treaty obliges the European Council to take into account the elections of the EP, the European Parliament cannot formally propose its own candidate, and national governments are under no legal obligation to pick any of the parties’ lead candidates. The nomination of Spitzenkandidaten, however, is a way for the European Parliament of imposing its own candidate on the European Council. Providing its own candidate with the democratic legitimacy conveyed by the vote of Europe’s citizens creates significant pressure on national governments to nominate the elected candidate to accept informally, if not formally, the Parliament’s right to appoint the EU’s executive (Schimmelfennig 2014). Hence, the potential impact of the Spitzenkandidaten was not confined to the electoral arena; a primary concern was the inter-institutional dynamics of the European Union, and competing visions of democracy: a federal vision where the European Parliament is given a democratic mandate by citizens to decide on a politicized European government, the Commission, and an intergovernmental vision, where national governments retain the powers to decide on the top post for the largely technocratic executive. Much depended on the campaign itself, however. For the European Parliament’s argument to be convincing, European voters would also need to take notice of the competing candidates. A PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGN? THE ROLE OF SPITZENKANDIDATEN Five of the seven Euro-parties that made up the major political groups in the European Parliament announced candidates for the European Commission Presidency in advance of the elections. The largest Euro-party, the centre-right European People’s Party, nominated the former Prime Minister of Luxembourg, Jean-Claude Juncker; the centre-left Party of European Socialists confirmed the President of the European Parliament, Martin Schulz, as their nominee; the third-largest grouping, the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe, nominated the former Belgian Prime Minister Guy Verhofstadt; the Party of the European Left nominated the head of the Greek party SYRIZA, Alexis Tsipras, as their candidate; and the European Green Party nominated two candidates for EU Commission President, both of whom were chosen by citizens in an online open primary: José Bové and Ska Keller. Only the Eurosceptic right-wing Euro-parties, the Alliance of European Conservatives and Reformists (AECR) and the Movement for a Europe of Liberties and Democracy, did not nominate any candidate. 1534 Journal of European Public Policy But did this Presidential horse-race change the nature of the 2014 European election campaigns, as the EU institutions were hoping? The context of these elections meant that ‘Europe’ was more salient than in previous EU elections, albeit for reasons that were entirely unconnected to the treaty modification of the election of the Commission President. The change in environment was rooted in the global financial crisis, and the subsequent sovereign debt crisis that had engulfed Europe since the 2009 elections and which made the issue of European integration highly salient in the public debate across Europe. In a recent study of the public debate in six member states, Kriesi and Grande (forthcoming) show that the crisis has resulted in a remarkable increase in the salience of the Euro and EU politics in national media outlets, which corresponds with major events in the crisis, such as the onset of the Greek crisis in early 2010 and the subsequent Greek bailout, the bailout of Ireland in the autumn of 2011 and the agreement on the Fiscal Compact. They conclude that ‘the debate [on the Euro crisis] has been exceptionally salient and has contributed to the increased visibility of Europe in the politics of the European nation-states’ (Kriesi and Grande forthcoming: 24). Survey data also show that citizens during the same period become increasingly aware the Euro crisis and more likely to hold the EU, rather than their national governments, responsible for the economic circumstances in their country (Hobolt and Tilley 2014). European issues were thus more prominent than in any previous European elections, yet nonetheless the campaigns continued to be dominated by national parties, national politicians and national political issues, or at least a national perspective on European issues. Hence, the ‘European perceptive’ was largely lacking from these national campaigns. The lead candidates did make efforts to run a campaign which was distinctly European in its outlook. The most high-profile innovation was the introduction of televized debates between the ‘Presidential candidates’. Between 9 April and 20 May 2014, nine televized debates took place across Europe, and four of these included at least four of the lead candidates. They were conducted in French, English and German, and were broadcast on the internet, on Euronews and on selected national channels. A post-election survey of citizens in 15 EU countries5 reveals that 15 per cent of European citizens claim to have seen at least one of the TV debates (AECR 2014). The debates generated most interest in Luxembourg (36 per cent of respondents had watched one of the debates), Greece (26 per cent) and Spain (20 per cent), whereas only 6 per cent of Dutch and British citizens had seen any of the debates. Social media was also used to generate interest in the campaign and the candidates. During election week, the #EP2014 hashtag was used in more than one million tweets to discuss the elections. The biggest volumes of conversation were recorded in France, Italy, Spain and the UK. The impact of the lead candidates on the campaign varied systematically across countries. Generally, European election campaigns are rather lowprofile lacklustre affairs (De Vreese et al. 2006; van der Eijk and Franklin 1996). In addition, the Spitzenkandidaten faced distinct challenges. S.B. Hobolt: The role of Spitzenkandidaten in the 2014 European Parliament elections 1535 Importantly, despite the fact that the lead candidates had held important posts inside the EU and in their own member states, they were largely unknown outside their country of origin before the start of the campaign. Moreover, the EU lacks a common ‘public sphere’, a common media and a shared language in which to discuss political matters. The lead candidates’ impact on national campaigns was therefore largely determined by the extent to which national party leaders and the national media involved the European candidates in their national campaign. The situation varied between member states. In Great Britain, national leaders deliberately disassociated themselves from the candidates and the Spitzenkandidaten initiative itself. Similarly, in Italy, Martin Schulz’s presence was virtually non-existent as the Partito Democratico had chosen not to associate the German candidate with its campaign (CEPS 2014). On the other hand, in France Martin Schulz played a visible role in the Socialist Party’s campaign. Unsurprisingly, Schulz also featured very prominently in the Social Democrats (SPD) campaign in Germany, and one SPD poster even highlighted that a vote for the SPD was the only way to vote for a German Commission President, hinting that a vote for the Christian Democrats was an indirect vote for a Luxembourgian President. Jean-Claude Juncker, Guy Verhofstadt and José Bové also featured visibly in their national media during the campaign. To assess the impact that the lead candidates had on various campaigns across countries, we can use the AECR-commissioned post-election survey in 15 countries, where voters and non-voters were asked directly after the elections about the degree of awareness of the political parties and candidates at the European level (AECR 2014). Figure 1 shows significant variation in the awareness of candidates for the Commission Presidency. Knowledge of specific candidate names was clearly highest in the home countries of the lead candidates: 55 per cent of citizens in the Luxembourg and 25 per cent of citizens in Germany and Belgium – the home countries of Juncker, Schulz and Verhofstadt – could give the names of at least one of the candidates when unaided.6 In contrast, only 1 per cent of British respondents were able to recall any of the lead candidates’ names. Unsurprisingly, there is also a close relationship between knowledge of individual candidates and reported viewing of one of the televized debates. General awareness that the Euro-parties had nominated a candidate, and hence that a vote in the European elections meant the indirect support of a candidate for the European Commission, was significantly higher, however. Of voters questioned in the 15 EU countries, 41 per cent said that they were aware of ‘the claim that when you made a choice to vote for a party in the European elections you also voted, indirectly, to support a specific candidate as the President of the European Commission’. Levels of awareness of this indirect support for a candidate also varied significantly across countries, and was highest in Luxembourg, France, Germany and Italy, and lowest in the more Eurosceptic countries, the UK, the Netherlands, the Czech Republic and Denmark. 1536 Journal of European Public Policy Figure 1 Public awareness of Spitzenkandidaten Source: AECR/AMR post-election poll of awareness of political parties and candidates (AECR 2014). What was the impact of voting behaviour? Turnout did not increase, as many had hoped, but remained at the low level of 43 per cent across the EU. Voter turnout increased in Germany, France and Greece, where awareness of Spitzenkandidaten was high (see Figure 1). Some have argued that this boost in turnout was owing to the role played in the campaign by lead candidates. However, others have attributed the higher turnout in some countries, such as France, the UK and Greece, to the mobilizing efforts of anti-EU and far-right parties that performed better than in previous elections. In terms of changing voting behaviour, it is plausible that the Spitzenkandidaten added to the appeal of parties (or the opposite) in some countries, such as Germany, Belgium, France, Greece and Luxembourg, where a significant group of voters were aware of the candidates. It seems unlikely, however, that it was a major factor in swaying voters for or against parties, not least because none of the candidates were ‘incumbents’ defending their record in office. The majority of Europeans did not vote in these elections, let alone take an interest in the choice between specific candidates. While there was a stronger ‘European dimension’ in the 2014 European Parliament elections, this was primarily owing to the anti-establishment, anti-immigration Eurosceptic parties that won the elections in France, Great Britain and Denmark and performed well in a number of other EU countries. This debate for or against the EU and for or against open borders was not one that was articulated in the debates between the Spitzenkandidaten, where the candidates by and large presented a more traditional pro-European, S.B. Hobolt: The role of Spitzenkandidaten in the 2014 European Parliament elections 1537 federalist message (that was at least the case for the three main candidates, Juncker, Schulz and Verhofstafdt). In other words, the Spitzenkandidaten did not define the agenda of the 2014 European elections, nor did they greatly enhance the public’s interest in the elections. Does that mean that this attempt to create a quasi-parliamentary system in the EU was a failure? THE ENDGAME: (S)ELECTING THE COMMISSION PRESIDENT While the European Parliament’s initiative to introduce Spitzenkandidaten may not have transformed the nature of the 2014 European elections, it did radically alter the process of selecting the successor to José Manuel Barroso. Despite losing more seats than any other group, the EPP remained the largest political group in the European Parliament after the elections, and its lead candidate, Jean-Claude Juncker, was thus seen as the Parliament’s choice for Commission President. During the election campaign, the Spitzenkandidaten repeatedly emphasized that it was ‘unthinkable’ that one of them would not become the Commission President, whereas national governments did not accept that ‘taking into account the elections’ would imply automatically nominating the European Parliament’s chosen candidate. After the elections, the debate over whether the winning Spitzenkandidat was indeed the ‘democratic choice’ intensified. All governments – with the exception of the British and the Hungarian government – who campaigned against Juncker and the right of the Parliament to choose a candidate – either openly came out in support of Juncker or stayed silent on the matter. The German Chancellor, Angela Merkel, who had originally said that the EP and the European Council should be jointly responsible for the election of the Commission President also came out in support of Juncker after German media made it clear that any other choice would be viewed as ‘undemocratic’. Similarly, the French President, François Hollande, said it was important to respect the spirit of the European elections. Some went even further, such as the Austrian Chancellor, Werner Faymann, who said that ignoring the European Parliament election results would damage European democracy (Spiegel 2014). In the end, 26 of the EU’s 28 national governments voted in favour of nominating Juncker as Commission President in the European Council vote (Britain and Hungary voted against). With the nomination of Jean-Claude Juncker, the European Parliament won an important victory in the inter-institutional battle for power. By imposing one of the Spitzenkandidaten as the European Council’s nominee for Commission President, the Parliament set an important precedent for the future which weakens the power of the European Council to select its own preferred candidates. Critics have argued that this is a dangerous ‘power grab’ by the European Parliament. They contend that the choice of Juncker was primarily about the European Parliament reasserting its own power and that Juncker lacks a popular mandate, since only 8 per cent of voters could name Juncker (and 26 per cent when prompted) (e.g. Open Europe 2014). In contrast, advocates of the Parliament’s initiative have argued that any 1538 Journal of European Public Policy choice other than Juncker would ‘further undermine the shaky democratic credentials of the EU, and play into the hands of the Eurosceptics across the continent’ (The Guardian 2014). Ultimately, this debate is not about the specifics of the 2014 election campaigns or whether they provided a direct democratic mandate for Juncker’s policies as a Commission President. Few would argue that the details of his policy programme played any noticeable role in the elections. This debate is about different visions of democracy in the European Union: one where European policy-makers receive a democratic mandate and can be held to account by voters in European Parliament elections, and another where the only genuine source of democratic legitimacy in the EU is national parliaments and governments. The Spitzenkandidaten initiative is still in its infancy and it is too early to determine whether it has been a success or a failure. Proponents of the federal model of European democracy hope that it can, in time, transform European elections to ensure that they allow voters to choose between alternative visions for Europe and hold the EU executive to account for its actions. This would establish a system of parliamentary government more akin to that in member states with a more political, and politicized, Commission elected as the ‘EU executive’ by a majority in the European Parliament. In the shortterm, however, the major effect of these Spitzenkandidaten was not on the nature of the elections, but on the inter-institutional battle for power that took place after the elections. Biographical note: Sara B Hobolt holds the Sutherland Chair in European Institutions, at the London School of Economics and Political Science. Address for correspondence: Sara B Hobolt, Sutherland Chair in European Institutions, European Institute, London School of Economics and Political Science, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE, United Kingdom. email: s.b.hobolt@lse.ac.uk NOTES 1 In 2007 the Eurobarometer asked citizens across the EU whether members of the European Parliament (MEPs) sit in the European Parliament on the basis of their nationality or their political affinities. Only a third of respondents realized it was the latter. Indeed, in that same survey in 2007, less than half were willing to say that MEPs were actually directly elected, and only 1 in 10 knew that the next European Parliament elections were to be held in 2009. 2 European Parliament Resolution of 22 November 2012 on the elections to the European Parliament in 2014 (2012/2829(RSP)). 3 Commission Recommendation of 12 March 2013 on enhancing the democratic and efficient conduct of the elections to the European Parliament (2013/142/EU) 4 Standard Eurobarometer 80, Autumn 2013. 5 The survey was conducted by AMR GmbH Dusseldorf on behalf of the AECR. The poll was in the field on 25 and 26 of May on a sample base of 12,132 respondents across 15 EU countries (6,083 voters and 6,049 non-voters). S.B. Hobolt: The role of Spitzenkandidaten in the 2014 European Parliament elections 1539 6 ‘Can you name any of the candidates that have been nominated by the Political Parties at the European level to replace Jose Manuel Barroso as President of the European Commission?’ REFERENCES AECR (2014) ‘Post EU Election polling project’, Fieldwork conducted by AMR GmbH Dusseldorf, 25– 26 May, on file with author. CEPS (2014) ‘European campaign shackled to national parties’, available at http:// europolitics.info/eu-governance/european-campaign-shackled-national-parties (accessed 9 July 2014). De Vreese, C.H., Banducci, S., Semetko, H.A. and Boomgaarden, H.A. (2006) ‘The news coverage of the 2004 European Parliamentary election campaign in 25 countries’, European Union Politics 7(4): 477– 504. De Vries, C., van der Brug, W., van der Eijk, C. and van Egmond, M. (2011) ‘Individual and contextual variation in EU issue voting: the role of political information’, Electoral Studies 30(1): 16 –28. European Parliament (2013) ‘The power to decide what happens in Europe’, available at http://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/news-room/content/20130905STO18723/ html/The-power-to-decide-what-happens-in-Europe (accessed 9 July 2014). European Voice (2014) ‘No commitment from Van Rompuy to choose one of five candidates for Commission Presidency’, available at http://www.europeanvoice. com/article/no-commitment-from-van-rompuy-to-choose-one-of-five-candidatesfor-commission-presidency/ (accessed 9 July 2014). Føllesdal, A. and Hix, S. (2006) ‘Why there is a democratic deficit in the EU: a response to Majone and Moravcsik’, Journal of Common Market Studies 44(3): 533– 62. Franklin, M. and Hobolt, S.B. (2011) ‘The legacy of lethargy: how elections to the European Parliament depress turnout’, Electoral Studies 30(1): 67 –76. The Guardian (2014) ‘Juncker is the democratic choice to head the EU Commission’, Letter to The Guardian, 6 June. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jun/06/ eu-democratic-choice-eu-commission Habermas, J. 2012. The Crisis of the European Union: A Response, Cambridge: Polity Press. Hix, S. 2008. What’s Wrong With the European Union and How to Fix It, Cambridge: Polity Press. Hix, S., Noury, A. and Roland, G. (2006) ‘Dimensions of politics in the European Parliament’, American Journal of Political Science 50(2): 494– 511. Hix, S., Noury, A. and Roland, G. (2007) Democratic Politics in the European Parliament, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Hix, S. and Marsh, M. (2007) ‘Punishment or protest? Understanding European Parliament elections’, The Journal of Politics 69(2): 495 –510. Hix, S. and Marsh, M. (2011) ‘Second-order effects plus pan-European political swings: an analysis of European Parliament elections across time’, Electoral Studies 30(1): 4 – 15. Hobolt, S. B. and Franklin, M. (2011) Electoral Democracy in the European Union, special symposium, Electoral Studies 30(1). Hobolt, S.B and Spoon, J.-J. (2012) ‘Motivating the European voter: parties, issues and campaigns in European Parliament elections’, European Journal of Political Research 51(6): 701– 27. Hobolt, S.B., Spoon, J. and Tilley, J. (2009) ‘A vote against Europe? Explaining defection at the 1999 and 2004 European Parliament elections’, British Journal of Political Science 39(1): 93– 115. 1540 Journal of European Public Policy Hobolt, S.B., and Tilley, J. (2014) Blaming Europe? Responsibility without Accountability in the European Union, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Kriesi, H. and Grande, E. (forthcoming) ‘Political debate in a polarizing Union’, in O. Cramme, and S.B. Hobolt (eds), Democratic Politics in a European Union under Stress, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Majone, G. (1998) ‘Europe’s “democratic deficit”: the question of standards’, European Law Journal 4(1): 5 – 28. Majone, G. (2000) ‘The credibility crisis of Community regulation’, Journal of Common Market Studies 38(2): 273 –302. Marsh, M. (1998) ‘Testing the second-order election model after four European elections’, British Journal of Political Science 28: 591 – 608. Norris, P. (2000) A Virtuous Circle: Political Communications in Postindustrial Societies, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Open Europe (2014) ‘Does Jean-Claude Juncker have a “popular mandate” to become the next President of the European Commission?’, Press Release, 12 June, available at http://www.openeurope.org.uk/Article/Page/en/LIVE?id=20223&page=PressReleases (accessed 9 July 2014). Peter, J. and de Vreese, C.H. (2004) ‘In search of Europe – a crossnational comparative study of the European Union in national television news’, Harvard Journal of Press/ Politics 9(4): 3 – 24. Reif, K. and Schmitt, H. (1980) ‘Nine second-order national elections: a conceptual framework for the analysis of European election results’, European Journal of Political Research 8(1): 3 – 44. Rittberger, B. (2005) Building Europe’s Parliament: Democratic Representation beyond the Nation State, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Scharpf, F.W. (1999) Governing in Europe: Effective and Democratic? Oxford: Oxford University Press. Schimmelfennig, F. (2014) ‘The Spitzenkandidaten plot: the European Parliament as a strategic competence-maximizer’, available at http://europedebate.ie/spitzenkandidatenplot-european-parliament-strategic-competence-maximizer/ (accessed 9 July 2014). Spiegel (2014) ‘Commission crusade: Cameron outmanoeuvred in battle over Juncker’, 19 June 2014. Van der Eijk, C. and Franklin, M., with Ackaert, J. (1996) Choosing Europe? The European Electorate and National Politics in the Face of Union, Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.