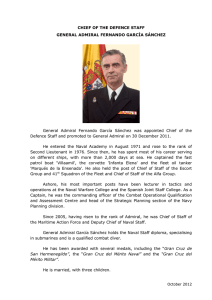

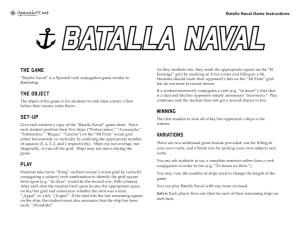

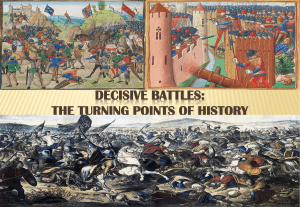

Toward a New Navalism Second Prize, CNO Naval History Essay Contest, Professional Historian Category, Sponsored by General Dynamics. By Andrew K. Blackley December 2021 Proceedings Vol. 147/12/1426 FEATURED ARTICLE VIEW ISSUE The Navy has enjoyed supremacy on the high seas for more than 70 years and has kept the ocean commons open for the benefit of all nations. But continental powers are rapidly expanding their naval forces and wielding new technologies that could render obsolete the force structure that has enabled the Navy to maintain its dominance. The ships the service currently is building are beset by problems, and its existing fleet is rapidly aging. To make matters worse, the government’s ability to finance new ship construction looks grim now and for the foreseeable future. The nation that once exulted in its naval victories has largely forgotten them, and it takes its sea services for granted. This could be describing the current situation for the U.S. Navy, but it actually refers to the predicament facing the British Admiralty in the mid-1880s. The Royal Navy was grappling with aging ships and forces stretched thin by global responsibilities, a muckraking press, government inquiries into its competence, and the growing French and Russian navies. Nonetheless, it emerged from the 19th century stronger than ever, with the largest, most modern fleet in the world and enjoying wide public and political support. How was this accomplished? In one word: navalism. The U.S. Navy today does indeed find itself in a similar situation to the 19thcentury Admiralty. Facing the renewed growth in naval power of its Cold War adversaries, budget constraints, and a Congress often skeptical of its requests for a larger fleet, the service should look to the past for direction on how to acquire the political capital to build the force structure it will need to meet future challenges. The path forward is to engage public—and hence political—support through a new navalism for the 21st century. The Birth of Navalism Arthur J. Marder, a historian specializing in British naval history, described navalism as “the big navy movement,” led by naval officers, politicians, and sympathetic civilians. In Britain, they used popular support to obtain the political clout needed to finance the rapid expansion of the Royal Navy in the 1890s.1 The navalism of that era can be said to have had two components: “hard” (or directed) and “soft.” The former was practiced by naval professionals, sympathetic publishers, and political allies, who defined a new blue-water naval strategy that required a bigger fleet, made the case for that naval expansion in Parliament, and then financed, designed, and built the ships they envisioned to carry out that strategy. “Soft” navalism was practiced by the popular press and advocacy groups, who used the new forms of mass communication that emerged in the late 19th and early 20th century to rouse patriotic fervor, build popular enthusiasm for the technological wonder that was the modern battleship, and ultimately persuade the public of the need for a powerful navy for both national security and national identity.2 The deft use of mass communication laid the groundwork that enabled the “hard” navalists to secure the political means to rebuild and expand the Royal Navy. Britain began to awaken from the “long lee” of Trafalgar in the 1880s, stirred in part by the muckraker W. T. Stead, whose articles in the Pall Mall Gazette called into question the ability of the Royal Navy to defend the British Empire.3 Admiralty intelligence reports pointed to a dangerous growth in the navies of France and Russia; in particular, France’s Jeune École strategy of guerre de course was seen as an existential threat to Britain’s sea trade.4 Public concern and agitation by naval officers such as Captain Charles Beresford led to parliamentary investigation and ultimately resulted in the Naval Defence Act of 1889.5 Journalist William T. Stead’s articles critical of the Royal Navy reached a wide public and are credited with igniting the navalist agitation in the press that led to the Naval Defence Act of 1889. Public Domain This groundbreaking legislation for the first time dictated the size of the Royal Navy, requiring that it be larger than the combined fleets of the two next-largest foreign navies, a standard that remained in effect until 1921. The act called for the construction of 10 new battleships and 38 cruisers within a five-year period.6 In the 30 years following passage of the act, the Royal Navy remained the world’s premier naval force, thanks to the willingness of the British taxpayer to maintain naval supremacy at almost any cost. That willingness was engendered through the work of a sympathetic press and furthered by the efforts of the Navy League of Great Britain, founded in 1895 for the specific purpose of promoting British sea power to the British public. The result was an unprecedented level of enthusiasm for the Royal Navy and a resolute belief in its importance to the economic well-being of the Empire and the prestige of the nation.7 Navalism also blossomed in the United States in the late 19th century, triggered by the realization that the post–Civil War Navy had deteriorated to such an extent that it was inadequate to defend the nation.8 In 1884, the Chilean Navy took delivery of the protected cruiser Esmeralda; her 10-inch rifled guns were said to be able to lob shells into San Francisco from a distance well outside the range of the defending shore batteries.9 There was no ship in the U.S. Navy to match her. The prospect of South American navies raiding U.S. coasts with impunity—and the realization that European powers equipped with modern warships could easily reassert themselves in the Western Hemisphere—provided the impetus for funding a “New Navy” of steam and steel warships. In 1883, Congress authorized construction of the “ABCD” protected cruisers and, with the Naval Act of 1890, the Navy’s first battleships. The New Navy would be led by a caste of highly trained, professional, and progressive naval officers.10 These officers found an intellectual home in the U.S. Naval Institute and the Naval War College. The 1890 publication of Alfred Thayer Mahan’s seminal The Influence of Seapower Upon History: 1660–1783, with its emphasis on the importance of global sea power, was a product of this intellectual flowering and provided the foundation for a new American navalism. Thus began the transformation of the U.S. Navy from a peace force of cruisers and coast defense monitors to a fleet of modern battleships capable of defending the nation on the high seas. The New Navy gained great popular support by its success in the SpanishAmerican War, which was colorfully documented by an enthusiastic press. Mahan also wrote dozens of articles that appeared in popular magazines that explained the imperatives of sea power to the average citizen.11 The directed navalism of the professionals, combined with this emerging soft navalism, induced successive Congresses to appropriate the funds to build an ever larger and more capable fleet, one that would show that the United States was a world power with global reach. Keenly aware of the importance of public opinion, President Theodore Roosevelt worked to build popular and political support of the Sea Services. The Great White Fleet’s around-the-world transit in 1907-08 was a public relations triumph. Credit: U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive The ascension to the presidency of consummate navalist Theodore Roosevelt accelerated the growth of the Navy. Keenly aware of the importance of public opinion, Roosevelt urged creation of the Navy League of the United States in 1902 to build popular and political support. The around-the-world transit of the Great White Fleet in 1907–8 not only demonstrated the technical prowess of the U.S. Navy, but also was a public relations triumph.12 Roosevelt’s successors continued his naval expansion. By the end of World War I, American navalists had succeeded in transforming a lackluster navy into one that was second to none. Navalism is Not a Dirty Word The term “navalism” has different connotations for different audiences, and it has acquired a distinctly bad reputation in certain quarters. Some historians see American navalism as having been driven by the desire to create an “imperial” navy, useful for dominating the Caribbean and Central America by gunboat diplomacy and acquiring possessions in the Pacific by force.13 The navalists of Edwardian Britain and Wilhemine Germany stoked the nationalist sentiments of their people in a race to build more and better dreadnoughts, and the popular antagonism that was engendered is believed by some to be a contributory cause of World War I.14 An extension of Germany’s militarist culture, the Kaiserliche Marine’s ostensible purpose was to secure Germany’s colonial possessions, but its real purpose was to threaten the dominance of the Royal Navy “between the Thames and Heligoland.” British and American navalists of the era saw things differently, and they distinguished their brand of navalism from that of the naval militarists. Pax Britannica ensured that the trade of all nations could pass unmolested on the high seas and that the independence of the former Spanish colonies was preserved. American navalists saw the emergence of the United States as a great power wielding the “big stick” of naval force as a positive development for the world. Ensuring the security of the nation first and foremost, U.S. sea power would bring the blessings of free trade and democracy to the former colonies of despotic regimes and help modernize the undeveloped world.15 According to Sir Julian Corbett, the British Empire’s promotion of free trade and protection of the ocean commons was a mark of its legitimacy: “For an Empire to endure it must be felt by the rest of the world to be a convenience. Let it once lose hold of this fundamental secret and sooner or later the nations will combine to remove it as a common nuisance.”16 This “fundamental secret” separates the navalists of the West from the naval militarists of authoritarian regimes. Western sea power has been more than just a convenience; it has been the protector of the free world. British, U.S., and Allied sea power helped secure victory in two world wars. Postwar, U.S. sea power peacefully assumed the mantle of leadership from the Royal Navy and has maintained the freedom of the seas to the present day. However, the authoritarian regimes of the world’s two great continental powers, China and Russia, now seek to challenge the West’s leadership. In particular, the rapid transformation of the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) into a large blue-water force threatens to upset the current order in the Indo-Pacific. China’s command economy has been able to finance and build new warships on a scale beyond that needed for the reasonable defense of its national interests—and without the need for public approval. The geopolitical outlook of the ruling Communist Party and President Xi Jinping is based on a centuries-old Sino-centrism of obeisance to the central state by vassal clients. Non-Chinese states may benefit from the relationship, but only if they conform to the desires of the central power.17 The parallels between Wilhemine Germany’s sea power gambit and China’s creation of a huge blue-water fleet to challenge U.S. dominance at sea are striking. Germany’s effort ultimately failed because of the British public’s resolve to bear the cost necessary to maintain naval supremacy—a resolve built by British navalism.18 If the United States and its allies want to maintain the current rules-based world order, they must show a similar resolve. Maintaining their sea power will require a massive and sustained reinvestment. The political support for this effort can be obtained through a thoughtful application of a New Navalism for the 21st century. The New Navalism The U.S. Navy was an important contributor to the West’s Cold War victory; however, the “peace dividend” that followed began a process of disinvestment, and U.S. naval supremacy was taken for granted.19 The “pivot to Asia” that began in the Obama administration was a response to the rise of China as a global competitor, but even before then strategists were sounding the alarm.20 The work of directed navalism has been ongoing, working to develop a strategic vision to meet the new challenges. The Naval War College and the U.S. Naval Institute have been in the forefront of this effort, and the current American Sea Power Project is an outstanding example of the intellectual firepower they bring to bear. The work of “soft” navalism, however, has not kept pace. There is no strategy to engage public opinion. Recently, Representative Elaine Luria (D-Va.), speaking about the lack of details in the October release of the Pentagon’s Battle Force 2045, said: We want to do more, but I really feel like the Navy should do a better job communicating—not just to us, who are going to put the pieces together in the National Defense Authorization Act, but to the American public about why this is so essential to our national defense. . . . You need to build a Navy. A Navy to do what?21 Answering “what” the Navy intends to do, and explaining it to policy-makers, is the job of directed navalism. Communicating that to the American public falls into the category of soft navalism. Soft Navalism Hell Divers (1931), filmed with cooperation of the Navy Department, showcased carrier-based aviation and demonstrated the impact of “soft” navalism. The film was a box office hit, and its aviation sequences thrilled audiences. Credit: Dr. Macro The explosion in new avenues of communication in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including print and then film media, was fully leveraged by the navalists of the time to spread the gospel of sea power and preach the importance of naval defense.22 Modern navalists will do well to follow their example. In 1929, the Chief of Naval Operations created a Motion Picture Board for the specific purpose of engaging with Hollywood producers to reach the American public. By 1941, no less than 40 films had been made that displayed the Navy’s latest technology: submarines and carrier-based aircraft. The films successfully portrayed the service as a modern and exciting organization with a vital mission.23 Soft navalism in the 21st century must use the proliferation in new forms of digital communication to promote sea power, with messaging tailored to a variety of diverse audiences. The Navy needs to broaden its messaging to reach not only those inside the Beltway, but also the general public, to educate them on why the Navy is critical to the well-being and prosperity of the nation and the world. Some of the following suggestions could help the New Navalism succeed: Show the Fleet. Fleet Weeks are popular events. The Los Angeles Fleet Week draws a quarter million visitors every Labor Day weekend.24 This should be replicated in as many locations as possible, including on the Great Lakes and the nation’s inland waterways. The launching and commissioning of new ships should be another cause for public celebration. Celebrate Navy Day. Established in 1922, this event was a public relations success in the interwar period, generating a great deal of popular support.25 It should be reimagined and relaunched on its 100th anniversary. Support the U.S. Naval Institute. The Institute continues to enjoy great success with its traditional publishing efforts and its online presence. USNI News enjoyed a large increase in its reach in 2020.26 Every person reading this should be a member. Every career officer and civilian who believes in sea power should consider becoming a Life Member. Support the Museums. There are more than six dozen warships preserved as museum ships across the country, as well as many other museums devoted to the Sea Services and naval aviation. They tell the Sea Services’ story like no other source and are great places to promote sea power to a receptive audience. Support the Navy League. Military members and civilian employees are prohibited from lobbying. The Navy League of the United States, however, can and does educate the public and Congress on the importance of sea power to the nation’s defense and economic well-being. With a large membership and hundreds of local chapters, it is well placed to promote the Sea Services. Engage the Midwest. The Navy needs to think strategically about how to win broader public support. One way is by creating more jobs in the Midwest, an area with little defense-related work.27 Fincantieri has obtained the contract to build the frigate Constellation and nine additional sister ships in its Marinette, Wisconsin, yard, and it has indicated that if more work follows, it might open a second yard.28Locating another shipyard on the Great Lakes would garner support from the key congressional delegations. Job creation and the presence of the Navy’s ships in the waters of the Heartland are ways to gain public and political support. ‘A Compelling and Enduring’ story For New Navalism to succeed, support for it must extend over successive presidential administrations and be funded by successive Congresses, regardless of which party has the White House or control of the House and Senate. The late Rear Admiral Wayne Meyer, referring to the Aegis program, said that for a new vision to succeed, the visionaries must be able to tell a “compelling and enduring” story to the decision makers.29 If the Navy’s plans to meet the challenges of the future are to be successful, they must gain the approval of the ultimate decision-maker, the American taxpayer. All the new technologies, operational genius, and grand strategies devised by hard navalism cannot come to fruition without the political will to make it happen, and that depends on broad public support. Building that support through the communication of a “compelling and enduring” story will be the task of the New Navalism. 1. Arthur J. Marder, The Anatomy of British Sea Power: A History of British Naval Policy in the Pre-Dreadnought Err, 1880–1905 (Hamden, CT: Archon Books, 1940), 4. 2. Bradley M. Cesario, “The Admiralty, Popular Navalism, and the Journalist as Middleman, 1884–1914” (doctoral dissertation, Texas A&M University, May 2016), 13. I am indebted to Cesario for the concepts of hard and soft navalism. In this paper, “soft navalism” includes the use of mass market media aimed at the general public. 3. W. T. Stead, “What Is the Truth about the Navy,” The Pall Mall Gazette, 15 September 1884, www.attackingthedevil.co.uk/pmg/navy.php. Stead was editor of the Gazette and a crusading journalist. Using information provided by the navalists and serving officers such as Jackie Fisher, he alleged that the Royal Navy was weak and technologically inferior, especially compared to France. 4. Roger Parkinson, The Late Victorian Navy, The Pre-dreadnought Era and the Origins of the First World War (Woodbridge, UK: The Boydell Press, 2008), 102–5. The French Minister of Marine in 1886 ordered the construction of new classes of fast cruiser and oceangoing torpedo boats—the first aimed at British commerce, the second at attacking British ironclads. 5. Parkinson, The Late Victorian Navy, 94–99. Beresford was a member of Parliament and was appointed Junior Sea Lord. In that position he advocated for the creation of the Naval Intelligence Division using a combination of aristocratic connections and press sensationalism. His allegations of naval weakness proved crucial in passage of the Naval Defence Act. 6. Parkinson, 113. Parkinson argues that British weakness was exaggerated by the navalists. 7. Parkinson, 164. 8. Kenneth J. Hagan, This People’s Navy (New York: The Free Press, 1991), 180–81. In 1873, a Spanish warship seized the Virginius, a U.S. registered former blockade runner smuggling guns into Cuba, and some of the American crew were executed for piracy. The Navy Department found itself without a serviceable ironclad and instead relied on diplomacy to avoid a potentially disastrous war with Spain, which at that time had a more modern navy. 9. “We Cannot Fight the Chilean Navy,” Army and Navy Journal 23, no. 1 (1 August 1885): 24. 10. Scott Mobley, Progressives in Navy Blue (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2018), 267– 68. Mobley’s thesis is that the American naval officers of the Gilded Age transformed their culture from “mariner-warrior” to “warrior-engineer” to meet the challenges of rapidly changing technology. 11. Alfred Thayer Mahan, John B. Hattendorf, and Lynn C. Hattendorf, “HM 7: A Bibliography of The Works of Alfred Thayer Mahan” (1986), Historical Monographs, 7. 12. See James R. Reckner, Teddy Roosevelt’s Great White Fleet (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2001), 157–59. The success was tarnished somewhat by Henry Reuterdahl’s muckraking article “The Needs of Our Navy” in McClure’s in January 1908. The article was written in part by William S. Sims and exposed some serious design faults in the ships of the New Navy—a cas of Sims and the progressives using soft navalism to promote changes in the internal operations of the Navy. 13. See Mark Russel Shulman, Navalism and the Emergence of American Seapower, 1882– 1893(Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1995), 159–61. Shulman describes how the USS Bostonand her Marines were used to intimidate the Hawaiian royal house into submission. 14. Jan Rüger, The Great Naval Game: Britain and Germany in the Age of Empire (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 248–49. Rüger’s thesis is that the intense Anglo-German naval rivalry was part of a greater “theatre of power and identity” that fed German paranoia and severely limited diplomatic efforts to keep Great Britain out of the war after Germany declared war against Russia on 1 August 1914. 15. Mobley, Progressives in Navy Blue, 67. 16. Julian Corbett, The Spectre of Navalism (London, UK: Darling and Son, 1915), 8. 17. David K. Schneider, “How China Sees the International Order: A Lesson from the Chinese Classics,” War on the Rocks, 18 March 2021. 18. See Steven Wills, “The Hohenzollern Chines Navy?” Center for International Maritime Security, 24 September 2015. 19. CDR Paul S. Giarra and CAPT Gerard D. Roncolato, USN (Ret.), “The American Sea Power Project,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 147, no. 1 (January 2021). 20. Perhaps most effectively with the concept of “AirSea Battle” laid out by Jan van Tol et al. in 2010. See AirSea Battle: A Point of Departure Operational Concept (Washington, DC: Center for Strategical and Budgetary Assessments, 2010). 21. Sam LaGrone, “Navy’s Vision for Future Fleet Is Blurry Say Seapower Members Luria, Gallagher,” USNI News, 18 March 2021. 22. Cesario, “The Admiralty, Popular Navalism, and the Journalist as Middleman,” 331. Navalism found expression in the profusion of inexpensive print media that flourished thanks to high-speed presses, cheap paper, and colorful inks. The media could be cheaply transported by extensive rail and shipping networks. 23. Ryan Wadle, “Sea Power Goes Celluloid: Lessons from Interwar Era Naval Publicity,” Naval History 32, no. 1 (February 2018). 24. RADM Mike Statynski, USN (Ret.), “The USS Iowa Is Back in the Fight: How LA Fleet Week and the Battleship Iowa Museum Contributed to USNS Mercy’s COVID 19 Mission to Los Angeles,” Surface SITREP 36, no.2, (Summer 2020), 7. 25. Ryan Wadle, “First Rate Ideas: The Hidden History of Navy Day,” Naval History 31, no. 6 (October 2017). The event was amalgamated with Armed Services Day in 1948 and largely forgotten. It was resurrected by Admiral M Elmo Zumwalt in 1972. Originally celebrated on 27 October, Theodore Roosevelt’s birthday, Zumwalt moved it 13 October, the date of the founding of the Continental Navy in 1775. 26. U.S. Naval Institute Annual Meeting webcast, 19 May 2021. VADM Peter H. Daly, USN (Ret.), reported a 46 percent increase in page views for USNI News and an overall growth of 37 percent in online page views for USNI.org. 27. “Defense Contract Spending: A State-By-State Analysis,” Bloomberg Government, 2015. 28. Megan Eckstein, “Fincantieri Wins $795M Contract for Navy Frigate Program,” USNI News, 30 April 2020. 29. AirSea Battle, 123.