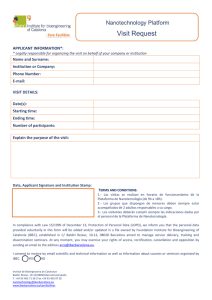

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/8957176 Tuberculosis screening among immigrants holding a hunger strike in churches Article in The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease · December 2003 Source: PubMed CITATIONS READS 19 81 11 authors, including: Joan A. Cayla Josep M Jansà Agència de Salut Pública de Barcelona European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control 431 PUBLICATIONS 6,156 CITATIONS 152 PUBLICATIONS 2,180 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Estanislau Alonso Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol 4 PUBLICATIONS 37 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Migration and health View project Use of geosocial network applications to promote HIV and STI testing between men who have sex with men (MSM) View project All content following this page was uploaded by Joan A. Cayla on 10 January 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. INT J TUBERC LUNG DIS 7(12):S412–S416 © 2003 IUATLD Tuberculosis screening among immigrants holding a hunger strike in churches P. García de Olalla,*† J. A. Caylà,*† C. Milá,‡ J. M. Jansà,* I. Badosa,* A. Ferrer,* M. Ros,‡ J. Gómez i Prat,‡ J. M. Armengou,* E. Alonso,‡ J. Alcaide‡ * Department of Epidemiology, Agencia de Salut Pública, Barcelona, † Autonoma University of Barcelona, Barcelona, ‡ DAP Ciutat Vella, Institut Català de la Salut, Tuberculosis Investigation Unit of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain SUMMARY S E T T I N G : In January 2001, approximately 600 immigrants held a sit-down and hunger strike in several churches in Barcelona to force the Spanish government to comply with demands to regulate their immigration status. Following the diagnosis of a case of smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) in one of the immigrants, we performed a large contact investigation. O B J E C T I V E S : To describe contact investigation procedures used in this setting and to evaluate contact investigation results. M E T H O D S : Demographic variables were collected, and tuberculin skin tests (TST) and chest radiograph examinations were performed. Odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated and logistic regression was used for multivariate analyses. R E S U L T S : A total of 541 TSTs were performed. Of these, 86% were read and 40.5% yielded a positive reac- tion with an induration 14 mm. In a multivariate analysis, the risk of presenting a TST induration 14 mm was found to be three times higher among those aged 35 years compared to those 24 years (OR 3.40; 95%CI 1.76–6.59), and for immigrants from Bangladesh (OR 3.14; 95%CI 1.16–6.10) and Pakistan (OR 2.04; 95%CI 1.11–3.73) compared to those from India. A total of 314 chest radiographs examinations were performed and three additional cases of TB were identified, yielding a TB prevalence of 0.7%. C O N C L U S I O N S : By focusing efforts and conducting targeted TB screening in this high-risk population, it was possible to complete the intervention in only 3 days. A high prevalence of TB infection and TB disease was found. K E Y W O R D S : tuberculosis screening; tuberculin skin test; immigrants TUBERCULOSIS (TB) is very unevenly distributed in the world: whereas some industrialized countries present annual incidence rates of under 10 per 100 000 population, in many poor countries rates are in excess of 300/100 000.1 The impact of these high TB rates, added to the precarious situations in which immigrants often find themselves, will be a determining factor for the epidemiology of TB in industrialized countries. In Spain, the implementation of new immigration regulations for foreigners in 2001 gave rise to a series of protests.2 In Barcelona, on 20 January 2001, some 600 immigrants without papers initiated a sit-down and hunger strike in several churches in the inner city, in an attempt to have their situation regularized. The hunger strike lasted 15 days, and ended after a tentative agreement was reached with the government. The majority of the strikers remained locked in until the agreement had been ratified, and the strike was thus prolonged for a total of 47 days. Our TB screening effort was promoted by the detec- tion of a case of infectious TB (pulmonary TB with haemoptysis and sputum smear-positive for acid-fast bacilli [AFB]) among one of the strikers. The index case was a 44-year-old male who had arrived in Spain from Pakistan 1 year before the hunger strike, and had a history of cough and expectoration for 5 months before being diagnosed. Since his arrival in Barcelona, he had shared housing in several different places with other immigrants. The patient participated in the strike 7 days before presenting with haemoptysis and being identified as having TB. In Spain, systematic TB screening is carried out only in prisoners, although recommendations for TB screening in migrants and other risk populations are being contemplated.3 The City of Barcelona Tuberculosis Control Programme performed a TB contact investigation, as is usual following exposure of large groups of persons to TB.3 However, due to the specific situation associated with the diagnosis of this index case, it is important to acknowledge that in addition to being a contact investigation, it represented screen- Correspondence to: Patricia García de Olalla, Servicio de Epidemiología, Agencia de Salut Pública de Barcelona, Pl Lesseps 1, 08023 Barcelona, Spain. Tel: (34) 93 238 4554. Fax: (34) 93 218 2275. e-mail: polalla@imsb.bcn.es Tuberculosis screening among immigrants ing of individuals at high risk for TB. All the immigrants involved in the strike were screened, regardless of whether or not they had been in contact. The aim of the present report is to describe the methods and results of the TB screening conducted among immigrants from low-income countries holding a hunger strike in churches in Barcelona, and who had unresolved problems with the regularization of their residence permits. METHODS Before initiating the TB screening, consent and aid was sought from the leaders of the various immigrant nationalities taking part in the strike, as well as with the leaders of the movement known as ‘Legalization and Work For All’, comprised of volunteer workers from several non-profit community organizations. A patient information brochure was prepared that explained the situation, the recommended interventions, and the plan of how these would be carried out. It was written concisely and simply, and translated into several languages (e.g., Arab, French, English, Urdu, Hindu). Health care workers and other collaborators who were from the same countries of origin as the strikers delivered the information. For those Figure 1 S413 who preferred not to identify themselves, we used alphanumeric identifiers instead of names. Tuberculin skin tests (TST) were performed using 2 TU PPD RT-23 (Tuberculina PPD Evans, Celltech Pharma, SA Madrid) and was read 48–72 h after placement. For the purpose of the analysis, we classified people as being infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis if they had indurations 14 mm, as among this population the influences of bacille CalmetteGuérin (BCG) vaccination and non-tuberculous mycobacteria are unknown.3 Treatment for latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) was a priority in those patients with TST 14 mm, because the probability of LTBI is considered very high. Chest X-ray examinations were performed for all persons with a positive TST result (defined as 5 mm induration) or anyone presenting with respiratory symptoms.4,5 Through a special arrangement with the Red Cross, persons requiring a chest radiograph were transported from the churches to the TB Control Programme. On the first day of this intervention, 205 chest X-rays were performed; an additional 109 were performed on subsequent days. When the TST was performed an epidemiological questionnaire was also administered, seeking the following information: name or other identifier, name of Distribution of striking immigrants in Barcelona by church. S414 The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease the church, country of origin, date of birth, and sex. Additional data collected included the TST result (induration size in mm) and whether or not a chest X-ray had been ordered and performed. When the strike was over, the groups of immigrants were contacted again, by approaching them directly and through announcements in the newspaper published by the Pakistani immigrant group of Barcelona, to facilitate a follow-up control visit 2 to 3 months after the end of the exposure. Statistical analysis A descriptive analysis was performed using the variables collected. In bivariate analyses, the 2 test was used for comparison of categorical variables. Odds ratios (OR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used as the measure of association, and logistic regression in multivariate analysis was used to study predictors of TB infection using SPSS (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). RESULTS The locations of the sit-down strikes and the distribution of the strikers among the different churches are shown in Figure 1. There was considerable overcrowding in one church that housed 425 (78%) of the strikers. A total of 546 immigrants were screened, with an average age of 31 years (standard deviation 8 years, Table 1 Demographic and clinical characteristics of the 546 striker immigrants in Barcelona n (%) Sex Men Women Age group (years) 14–24 25–30 31–35 35 Unknown Country of origin Pakistan Bangladesh India Morocco Algeria Sub-Saharan Africa Eastern Europe South America Unknown Results of initial TST (induration in mm) Negative 5–14 mm 14 Positive TST prior to the strike Unknown Total TST tuberculin skin test. 544 (99.6) 2 (0.4) 92 (17) 173 (32) 141 (26) 122 (22) 18 (3) 205 (37.5) 112 (20.5) 88 (16.1) 80 (14.7) 6 (1.1) 16 (2.9) 15 (2.8) 2 (0.4) 22 (4.0) 180 (33.0) 98 (17.9) 189 (34.6) 5 (0.9) 74 (13.6) 546 (100) Figure 2 Prevalence of tuberculin skin test indurations by country of origin and induration size in mm. range 14–81). Demographic and clinical characteristics of the striker immigrants are shown in Table 1. Of the 546 immigrants, five had a known positive TST documented within the 2 months prior to the strikes and were not retested. From a total of 541 TSTs performed, 467 (86%) were read, and no test result was obtained for 74 (14%). When we compared these two groups (TST not read vs. TST read), the only statistically significant difference was a higher proportion of unread TSTs in persons from Morocco. Of the 467 tests read, 189 (41%) had indurations 14 mm. Figure 2 shows the distribution of TST results by country of origin, with persons from Bangladesh having a notably higher proportion of TST indurations 14 mm and persons from the category labelled as ‘other countries’ having a higher percentage of negative TST results. In both the bivariate and multivariate analyses, age and country of origin were significantly associated with indurations 14 mm (Table 2). Thus, TB infection was found to be three times higher among those aged 35 years than among those 24 years, and the Table 2 Factors associated with TST indurations 14 mm among 455 immigrants with complete data* Age (years) 24 25–30 31–35 35 Country of origin India North Africa Pakistan Bangladesh Others Cases (n 455) n (%) Crude OR† (95%CI) Adjusted OR‡ (95%CI) 79 (17) 152 (34) 118 (26) 106 (23) 1 1.66 (0.88–3.15) 1.96 (1.01–3.82) 3.09 (1.58–6.10) 1 1.56 (0.84–2.89) 2.09 (1.09–4.01) 3.40 (1.76–6.59) 72 (16) 64 (14) 169 (37) 102 (22) 48 (11) 1 1.12 (0.52–2.44) 2.04 (1.10–3.79) 2.50 (1.28–4.93) 1.19 (0.51–2.77) 1 1.30 (0.60–2.79) 2.04 (1.11–3.73) 3.14 (1.16–6.10) 1.11 (0.49–2.50) * Of 467 eligible contacts, age was missing for 12. † Bivariate analysis. ‡ Multivariate analysis. TST tuberculin skin test; OR odds ratio; CI confidence interval. Tuberculosis screening among immigrants risk of presenting a TST induration of 14 mm was 2.5 times higher for immigrants from Bangladesh than for those from India in the 455 contacts included in the model (Table 2). A total of 314 chest X-rays were performed and three cases of active TB were diagnosed, although M. tuberculosis culture was negative in all three. TB diagnosis was based on chest X-ray and in all cases by strong clinical evidence consistent with TB, and their improvement with a full course of anti-tuberculosis chemotherapy. Thus, the prevalence of TB among these immigrants, including the index case, was at least 0.7%. All four TB cases were pulmonary, and all underwent directly observed anti-tuberculosis treatment. Follow-up control examinations were carried out 2–3 months post exposure in 173/467 (37%) immigrants. Persons with follow-up examination included 55 of 287 with a positive TST (5 mm induration) at the first test. Of these 55, 16 presented a TST induration 14 mm. LTBI treatment was offered to those patients with a fixed address to ensure monitoring of treatment. Only five patients with indurations 14 mm fulfilled this requirement and agreed to LTBI treatment. The group with follow-up also included 118 of 180 persons with a negative TST at the first testing, among whom no TST conversions were observed on retesting. DISCUSSION This report describes a large screening effort to diagnose TB in a group of immigrants with unique difficulties limiting their access to health care: these people were sequestered in churches on a hunger strike, at risk of expulsion from the country because they lacked the necessary residence permits. They had also probably faced precarious health conditions in their country of origin and during their period of displacement. On arrival in Spain, they were no doubt also exposed for an undetermined length of time to factors that would increase their vulnerability to TB and other diseases.6,7 In recent years, in industrialized countries, there have been continued suggestions that the progressive immigration of people from poorer areas of the world has a direct impact in the rise of infectious diseases such as TB.8,9 This has been observed for some time in countries with low incidence of TB disease (i.e., Switzerland, the Netherlands, the USA10,11), but has only recently become evident in Spain, where TB incidence rates have been fairly high in recent years.12–14 Analyses of data from the Barcelona City TB Prevention and Control Programme show that the percentage of TB cases among foreign immigrants has risen from 7% in 1996 to 23% in 2000.15 This rise continued during 2001, when we identified 170 (34% of the total) cases of TB in immigrants, with the fol- S415 lowing distribution by country of origin: Pakistan 21%, Morocco 18%, Ecuador 13%, Peru 10%, Philippines 4%, India 3%, and other countries 31%.16 In the last few years we have observed a decrease of TB in the Spanish-born population and an increase among immigrants. Due to the lack of immigrants from Latin American and sub-Saharan countries participating in the hunger strike, we could not obtain a broader view of TB infection and disease rates in these populations, but, based on our surveillance data, these groups of immigrants also contribute significantly to TB morbidity in Barcelona. The high TB prevalence rate observed in the present study is consistent with the published estimates of TB burdens for some of the countries of origin.17 This high rate, combined with a number of other factors (poverty and crowded conditions during displacement, poor nutrition and a stressful environment on arriving in Spain), probably favoured the development of TB disease and transmission of TB infection. An important limitation of our intervention was that the 2–3 month follow-up examination was accomplished for only 37% of those tested initially, a low percentage compared to other studies.18 LTBI treatment was offered to those patients with indurations 14 mm along with a fixed address to ensure clinical and routine laboratory monitoring of treatment. If screening efforts such as ours were coordinated with immigration authorities and were free of any form of discrimination, the follow-up and final outcome rates could be much improved. Another study limitation was that the relationship between the four active cases identified could not be confirmed using molecular epidemiological techniques, as three of the four cases had negative cultures for M. tuberculosis, and without positive cultures it is not possible to determine whether these cases are due to recent transmission or reactivation of old infection. Given the length of the strike (about 7 weeks), it is possible that some of the persons who initially tested positive were in fact converters. On the other hand, the lack of TST conversion mitigates against transmission. All of this demonstrates the difficulty of trying to measure recent transmission in a population with a high background prevalence of TB. Access to health services for immigrants to our country could be accomplished by providing them with a health card giving them the right to health care with the same conditions as all Spanish citizens. However, even under such a scenario, we believe that it is unlikely that an evaluation for TB screening would always be performed when an immigrant consults a doctor; it would therefore be preferable to ensure systematic referral to a TB or immigration control center. The optimal solution would be to link the requisite medical examinations to the process of issuing the residence permit, while ensuring that this S416 The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease link does not result in discrimination, even among those diagnosed as TB cases. In conclusion, the rates of TB infection are very high among specific groups of migrants coming to Spain. The patterns of TB infection and disease among immigrants in Spain mirror those of their countries of origin. Coordination among public health services, TB clinics, and migrant services are necessary when providing health care services for immigrant populations. Acknowledgements We are grateful to Margarita E Villarino, Research and Evaluation Branch, National Center for HIV, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for a critical review of this manuscript. We extend our sincere thanks to all collaborators and healthcare workers who facilitated this work: S Raja, A Ahmed, H Ouarab, A Attaleb, M Abdoul, G E Embumba, T Rafi, F Shabi, A Razaq, J Sing, A Lamine, S Sharif, M Abasi, M Farooq, M M Ilyas, and J Mugal. This work was partially financed by a grant from the Health Research Foundation (FIS), file 00/0793. References 1 World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Control: WHO Report, 2002. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2002. 2 Ley Orgánica 8/2000, de 22 de diciembre, de reforma de la Ley Orgánica 4/2000, de 11 de enero, sobre derechos y libertades de los extranjeros en España y su integración social. Boletín Oficial del Estado, n 307, 23 diciembre 2000. 3 Unidad de Investigación en Tuberculosis de Barcelona (UITB). Documento de consenso sobre el estudio de contactos en los pacientes tuberculosos. Med Clin (Barc) 1999; 112: 151–156. 4 Grupo de Trabajo sobre Tuberculosis. Consenso nacional para el control de la tuberculosis en España. Med Clin (Barc) 1992; 98: 24–31. 5 Unidad de Investigación en Tuberculosis de Barcelona (UITB). Documento de consenso sobre la prevención y control de la View publication stats 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 tuberculosis en España. Med Clin (Barc) 1999; 113: 710– 715. Decosas J, Kane F, Anarfi J K, Sodji K D, Wagner H U. Migration and AIDS. Lancet 1995; 346: 826–828. Jansà J M, Villalbí J R. La salud de los inmigrantes y la atención primaria. Aten Primaria 1995; 15: 320–327. Zuber P L, Binkin N J, Ignacio A C, et al. Tuberculosis screening for immigrants and refugees. Diagnostic outcomes in the state of Hawaii. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996; 154: 151– 155. Zellweger J P. Screening for tuberculosis in risk groups in Switzerland. Bulletin des Bundesamtes für Gesundheitswesen 1993; 41: 739–743. EuroTB and the national coordinators for tuberculosis surveillance in the WHO European Region. Surveillance of tuberculosis in Europe. Report on Tuberculosis cases notification 1998. St Maurice, France: EuroTB, February 2001. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reported tuberculosis in the United States, 2000. Atlanta, GA: CDC, August 2001. Rey A, Ausina V, Casal M, Caylà J, De March P, Moreno S. Situación actual de la tuberculosis en España. Una perspectiva sanitaria en precario respecto a los países desarrollados. Med Clin (Barc) 1995; 105: 703–707. Durán E, Cabezos J, Ros M, Terre M, Zarzuela F, Bada J L. Tuberculosis en inmigrantes recién llegados a Barcelona. Med Clin (Barc) 1996, 106: 525–528. Vallès X, Sánchez F, Pañella H, García de Olalla P, Jansà J M, Caylà J A. Tuberculosis importada: una enfermedad emergente en países industrializados. Med Clin (Barc) 2002; 118: 376– 378. Rius C, Caylà J A, García de Olalla P, Vallès X, Jansà J M, Tost J. La tuberculosis en Barcelona. Informe 2000. Barcelona, Spain: Ajuntament de Barcelona, Institut Municipal de Salut Pública, 2001. Agencia de Salut Pública de Barcelona. Accessed 5 May 2003. http://www.aspb.es/proves/quefem/docs/tuberculosi2001.pdf Dye C, Scheele S, Dolin P, Pathania V, Raviglioni M. Global burden of tuberculosis: estimated incidence, prevalence, and mortality by country. JAMA 1999; 282: 677–686. Reichler M R, Reves R, Bur S, et al. Evaluation of investigations conducted to detect and prevent transmission of tuberculosis. JAMA 2002; 287: 991–995.