debussy dream

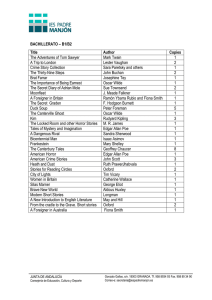

Anuncio

2 I

MARCH

I

963

Debussy's concept of the dream

EDWARD LOCKSPEISER

Chairman

PROFESSOR SIR

J·

A. WESTRUP (PRESIDENT)

of Turner's great picture of the sea, The Snowstorm,

Sir Kenneth Clark draws attention to Turner's preoccupation

with 'visions' and 'dr~arns'. These words, he says, 'were

commonly applied to Turner's pictures in his own day, and in

the vague, metaphysical sense of the nineteenth century they

have lost their value for us. But with our new knowledge of

dreams as the expression of deep intuitions and buried memories, we can look at Turner's work again and recognise that

to an extent unique in art his pictures have the quality of a

dream. The crazy perspectives, the double focuses, the melting

of one form into another and the general feeling of instability,

all these are forms of perception which most of us know

only when we are asleep. Turner experienced them when he

was awake'. 1

I propose to investigate in this paper Debtmy's knowledge

of the works of Turner and to suggest aesthetic parallels in their

concept of the dream. But before doing so it is desirable to

approach this concept in Debussy's work from a purely

musical viewpoint even though, despite many attempts at

analysis, his technique and methods of composition remain

extremely elusive. This is inherent in Deb1my's musical

character. He wrote no musical treatise; he occasionally gave

a few lessons but his pupils, Nicolas C,Oronio and Raoul

Bardac whom I was privileged to consult, were able to say

very little about his methods, and indeed his correspondence

with them speaks of composition only in generalities; and his

musical criticisms rigorously avoid any mention of technique.

IN HIS STUDY

1

Sir Kenneth Clark, 'Turner's Look at Nature', Thi Swulay Tunes, 25

October 1959.

49

50

DEBUSSY'S CONCEPT OF THE DREAM

We know from searching statements in Debussy's letters that

he was concerned with the power of memory, the functioning

of fantasies, the interpretation of symbols and the new significance of dreams, in particular the dream within a dream,

the labyrinth dream. These are matters which are partly

psychological and partly aesthetic, and if we try to see how

they affected his ideas on harmony, or rhythm, or form, we

are bound to confess that this new spirit that was breaking

through, this keener awareness of the life of the imaginative

mind, was so novel that any technique designed to express it

could only be evolved experimentally.

We have a valuable source, however, in the conversations

between Debussy and his former master Ernest Guiraud which

took place early in Debussy's career, and which were meticulously recorded with musical examples by Debussy's friend

and fellow pupil Maurice Emmanuel. 1 Debussy explained to

Guiraud not so much a system but an approach that should

allow for an expression of the ambiguous. He had worked out

the use of ambiguous chords, the aim of which was to undermine the rigidity of the tonal system and thus, as he believed,

to enlarge the range of harmonic experience. He argued that

since the octave consists of twenty-four semitones, twelve

ascending and twelve descending, arbitrarily reduced to

twelve to meet the requirements at the keyboard of equal

temperament, any kind of scale could in practice be built

without any allegiance to the basic C major scale. This need

not disappear, but it should be enriched by' the use of many

other scales, including the whole-tone scale and what he

cryptically calls the twenty-one note scale. (Giving each note

the name of its enharmonic counterpart, C sharp D flat, or

D sharp E flat, there are in fact twenty-one notes within the

octave.) Enharmony should be used abundantly and a plea is

made for a distinction between notes of the same enharmonic

value, that is to say between a G flat and an F sharp. The

major and minor modes are a useless convention. There

should be great freedom and flexibility in the use of major and

minor thirds, thus facilitating distant modulations, and

evasive effects should be produced by incomplete chords in

which the third is missing or other intervals are ill-defined.

' Published in A. Hofrec, lnJdits sur Debussy, Paris, 1942.

DEBUSSY'S CONCEPT OF THE DREAM

By thus blurring or drowning the sense of tonality (en noyant le

ton) a wider field of expression is ensured and seemingly

unrelated. harmonies can be approached without awkward

detours.

In illustration of this search for floating or incomplete

chords, Debussy pla ycd these successions of ninths and common

chords which, divorced from any sense of tonality, Guiraud

found theoretically unsound and meandering.

(Here was played a musical example from the notebook of

Maurice Emmanuel.•)

Such successions quickly became a commonplace, and we

may therefore have some difficulty today in seeing their

original purpose which was to create that sense of ambiguity

or of multi pie associations which, as I shall presently attempt

to show, was peculiar to the dream. The outcome of this

approach was twofold. The forms of music based on tonality

were disrupted, particularly the aspects of form concerned

with thematic development; and within the chord sequences

themselves a deliberate imprecision prevailed, (described by

Verlaine in his Art Poitique as the state in which 'findiru au

prlcis se joinf.) This presented an entirely new phenomenon.

A given note or chord in say La Cathedralt engwutie or us Sons et

ks Parfums tournent dan.r £'air du .soir may, if we wished, be

replaced by another note, another chord, without the work

suffering in an essential way. The alternative version would be

more or less beautiful but it would not shock or surprise. In the

Boston manuscript of Pellias et Milismuk' there are often

examples of single notes with many alternative versions, and

indeed at the rehearsal of this opera, when asked whether he

meant a C or a C sharp to be played, the composer himself

was not quite sure. Understandably, though he was unable

to see its significance, Saint-Saens described L'Apris-midi

d'unfllUIU as the equivalent in music not of a painting but of

the sight of an artist,s palette with its chance associations of

primary colours. 1

These features of Debussy,s musical language are we I

known. But what do they signify and what were the ideas

1

Sec Note 2.

'At the New England Conservatory of Music, Boston.

J

'Corrcspondance entrc Saint-Saens et Maurice EmmanucP, La R.ei:ut

l~luneak,

4

No. 2o6, 1947.

1t

DEBUSSY'S CONCEPT OF THE DREAM

that prompted them? As an expression of the unconscious, the

concept of the dream towards the end of the nineteenth

century was first of all a poetic concept and later, in the early

works of Freud, a scientific concept. It was not of course new;

this concept belongs in one form or another to artistic expres·

sion of all time. The novel aspect of the dream as illustrated in

the work of artists of Debussy's period, and in the work of

Debussy himself, derives from a rising to the surface of hidden

fantasies together with their symbolical and sexual significance.

The writer who principally orientated thought in this direction

was Edgar Allen Poe, who was in a sense a creation of the

French, while in French literature the outstanding figure in

this movement was Mallarme, possibly the last great poet of

the nineteenth century. The ideas of these two figures are at

the root of Debussy's inspiration.

Musicians have not been greatly concerned with the

meaning of Mallarme's poem L' Apres-midi d'un faune, held by

literary people to be the principal achievement of Symbolist

poetry. This is partly because it is a work of some obscurity,

but it is also because the music of Debussy is thought to speak

for itself and need not be referred, in detail, to the imagery of

Mallarme by which it was inspired. I do not think Mallarme's

ideas can be ignored. Mallarme's eclogue is an exploration of

the processes by which physical impulse first originates in the

imagination, is later defined in reality, and is eventually

transformed into a work of art.

Buried in its abstruse language is a philosophical treatise on

the life of the senses and the psychology of sublimation. It is

also an exploration of the borderlands between the conscious

and the half-conscious, the waking state and the state of

reverie. In his Introduction a la Psychanalyse de Mallarme'

Charles Mauron observes the deliberate confusion in L' Apresmidi between these various degrees of consciousness and

unconsciousness. The faun emerges from a dream, plays like a

child with the fantasies of his dreams, but satisfies his desires

only by plunging into sleep. The poet's art consists of never

allowing us to be quite sure if the faun is dreaming ('Aimai-je un

reve ?') or whether, when awake, he is aware of the distinction

between primitive desire and the sublimated artistic vision.

• Neuchatcl, 1950.

DEBU~Y'S CONCEPT OF THE DREAM

53

Another critic, Wallace Fowlie, similarly draws attention to a

duality of meanings in the poem. The dual meaning of the

opening line, 'Ces nymphes, je ks veux perp~tuer', this critic

suggests, represents a condensation of the entire work.

'Copulation', he explains, 'may well be one significance of the

afternoon's quest-the word 'perpetuate' is of a refined

elegance; and preservation by means of art may be the other'."

Indeed, duality of one kind or another is reflected throughout

the poem. There are two nymphs, one chaste, living on illusion,

the other experienced, sighing for love; and there are in

reality two fauns, both the lasciyious faun and the aloof,

objective faun watching himself wrestling with desire. The

faun actually addresses himself as another person. The desires

of neither are fulfilled; nor can they be since in the faun's

quest for the nymphs, as in his flute-playing, there is a con..

stant interplay between action and indolence.

There is a difference between the dreams of sleep and the

musings of reverie. The latter are considered by Mallarme to

be adolescent and even impotent. And from one viewpoint the

faun, too, is the adolescent artist anxious to make amorous

conquests but remaining more truly a poet. Here Mr. Fowlie

emphasizes that L' Apres-midi is 'MallarmC's most significant

inquest into the perplexing but omnipresent relationship

between the sexual dream world of the poet and his creative

life as a practising artist'. The imagery in the description of the

faun as an 'ingenuous lily', playing with blown-up grape skins,

his passion bursting like the purple pomegranate, is clearly

shot through with erotic associations. Yet the heart of the poem

is in a definition of sublimation. Mallarme attempts to trace in

lines, which I should like to read in French for the musicality

of the choice of words, the process in which desire first vanishes

into the dream and is then transformed into music:

Et de faire, aussi haut que l'amour se module

Evanouir du songe ordinairc de dos

Ou de ftancs purs suivis avec nos regards clos

U ne sonore, vaine et monotone ligne.

7

Wallace Fowlie, Mallann/, London, 1953.

54

DEBUSSY'S CONCEPT OF THE DREAM

In Alex Cohen's translation 1 this is rendered:

At just the height to which love modulates,

Pursuing them with veiled eyes, I'd expunge

The common dream of flank and back, to change

It to a monotone of sounding line.

I think we may see in the image of 'a sonorous, vain and

monotonous line', the origin of the flute solo at the opening of

Debussy's score. In the preceding lines the faun's fluteplaying is actually described as 'a long solo':

Qui, detournant a soi le trouble de la joue,

Reve, dans un solo long, ...

In lingering arabesques dreams of amusing

The beauty hereabout by falsely confusing

Its charm with the illusion song creates.

These lines, which bring us to the heart of Debussy's

inspiration, are interpreted by Mr. Fowlie thus: 'In the high

notes of the flute the entire experience of love may be reduced

into a single melodic line, vain and monotonous as all art is

when contrasted with the immediacy and necessity of experience. As he plays thus on his instrument, the faun is

master of himself and his feelings. He is able to follow inwardly

the dream of having seen the nudity of a nymph, her back and

side, and to sing of such a vision without experiencing the need

of acting upon it'.

(Here was played the opening

of 'L'Apres-midi d'un faune' .)

Debussy's expression of the dream is seen too in his life-long

attraction to the works of Edgar Allan Poe. Until recently it

was thought that Debussy's sketches for an opera on The Fall of

the House of Usher, were just one of the numerous ideas with

which he toyed during the latter part ofhis life. The publication

of the correspondence of Romain Rolland• allows us to form a

completely different view of this project. We learn here that as

early as 1890, three years before Pellias et Milisande, Debussy

was writing 'a symphony using psychologically developed

themes' based on The Fall of the House of Usher.

8

1

Published in E. Lockspciser, Dtbussy (Master Musicians), 1963.

Cahiers Romain Rolland, Vol. V, Paris, 1954.

DEBUSSY'S CONCEPT OF THE DREAM

55

Later this work inspired by Poe was to be an opera for the

production of which he signed a contract with Gatti Casazza

of the Metropolitan Opera in New York. 'Thorughout these

last days', he then wrote to his publisher Jacques Durand, 'I

have been busily at work on The Fall of the House of Usher. I

have found it an excellent means of strengthening one's nerves

against any form of fear. Yet there are moments when I lose

a sense of identity. When I am no longer able to perceive the

familiar objects around one, and if the sister of Roderick

Usher were suddenly to come in I shouldn't be extremely

surprised' . 10 The contract signed with the Metropolitan in

1 908 was for the production there of Usher together with the

Devil in the Belfry, another opera on a tale of Poe, in an ironic

vein on which Debussy had begun to work shortly after

Pellias in 1902.

In his study Edgar Allan Poe and France T.S. Eliot investigates

the far.reaching influence of Poe on the French literary mind

and states, 'there are aspects of Poe which English and American

critics failed to perceive' . 11 Poe was in fact almost entirely a

creation of the French-none of the writers in the rich generation

from Baudelaire to Paul Valery including Gide and Marcel

Proust escaped his fascination-and the aspect of Poe to

which they were drawn was the rising to the surface of unconscious fantasies. 'His most vivid imaginative realisations',

Eliot states, 'are the realisation of the dream'. Nearly all Poe's

tales with their dark symbolism of corridors and underground

passages, stagnant water and enveloping whirlpools, are in

essence dream tales, and although Eliot, like most other

English critics is censorious of Poe as a stylist, he does concede

that the Symbolist figures in French literature from Baudelaire

onwards saw in Poe an expression of the new sensibility that

they were themselves seeking, and that they were thus able to

interpret Poe for English writers in his true light.

Belonging entirely, in spirit and outlook, to his generation,

Debussy was similarly profoundly affected by Poe. He speaks

of the 'tyranny' the 'obsession' which Poe exerted over him. 11

Earlier critics ofDebussy, Arthur Symons and James Huneker,

drew attention to Debussy's affinity with Poe. They saw his

10

11

11

Letter of 18 June 1 go8, in Lettres <k Clawk Debussy 0. son iditeur, Paris, 192 7.

T. S. Eliot, •Edgar Poe et la France', La Table r<mde, Paris, December 1948.

Lettres inldius a Andre Caplet, edited by E. Lockspeiser, Paris, 1957.

DEBUSSY'S CONCEPT OF THE DREAM

work as a counterpart of the deliberate vagueness cultivated by

Poe, of his lugubrious moods, as a vision, too, of Poe's ethereal

women, Ligea and Morella, vanishing like MClisande before

they can be embraced.

But, of course, neither Symons nor Huneker, excellent

critics as they were, had quite the understanding of Poe's significance that we have now acquired. They were themselves part

of the movement that had sprung from this French influence of

Poe. And they were therefore unable to see, as we are today,

that the fantasies to which Debussy gave a musical expression

were almost Surrealist fantasies, the chaotic fantasies ofdreams,

such as we hear in the scene of the vaults in PelUas.

(Herewasplayedthesceneoftlzevaultsfrom'PelUasetMilisande.')

This association of Poe with Pelleas et Milisande is not

fortuitous. In the very month when he sets to work on PelUas,

in September r 893, Debussy in a letter describing his state of

mind to Ernest Chausson goes so far as to quote almost word

for word Poe's description of a sullen autumn day at the

opening of Th Howe of Usher. Poe,s tale opens: 'During the

whole of a dull, dark, and soundless day in the autumn of the

year, when the clouds hung oppr~ively low in the heavens, I

had been passing alone, on horseback., through a singularly

dreary tract of country, and at length found myself, as the

shades of evening drew on, within view of the melancholy

House of Usher'. And here is the letter of Debussy: 'It is all

very well; I cannot see beyond the sadness of the landscape of

my mind. Sometimes I pass days that are dull, dark and soundless like those of a hero of Edgar Allan Poe and I have with

this the romantic soul of a Ballade of Chopin. Solitude is

crowded with too many memories which we cannot shut out'. 11

Later in a letter to Andre Caplet we read that Poe 'although

dead exercises over me an almost agonising tyranny. I forget

the simple rules of behaviour and close myself up like a

brute beast in the House of Usher'. He told Robert Godet

that he could tell him things about Roderick Usher that would

make his beard fall off. 'You are my only friend', he

exclaims, 'alias Roderick Usher' .14

u 'Lettres ined.itcs a Ernest Chausson', La Reuue Musi&ak, Paris, December

1925.

" Lettres tk Claude Debussy a dncc amis, Paru1 1942.

DEBUSSY'S CONCEPT OF THE DREAM

57

The idea that Debussy had formed of Poe, both of his

personality and of his work, was very far from our present day

conception of him as a writer of creepy stories or as the

precursor of the crime story or the detective novel. It is clear,

from both the libretto of Usher and the musical sketches, that

Debussy was primarily concerned with the essentially soliptic

character of Roderick Usher; the enraged, self-devouring

lover guilty of loving his sister. 'Gelle que tu aimais tant', Usher

says of himself in Debussy's libretto, 'celle que tu ne devais pas

aimer' .1 r. Parent of the indecisive, Hamlet-like Pelleas, Roderick

perishes with the rise of the red moon, the same blood-red

moon, we note, that appears so dramatically at the end of

Salome and of Wozzeck, symbols in these operas, as in Usher of

love and of murder. The symbolism of this libretto with which

Debussy was so long concerned opens up an extraordinary

vision of what Debussy's art might have become had he lived

to bring fully to life Roderick's interior monologue. Because of

the illegibility of much of the musical manuscript it is difficult

to perform, but a few bars-literally a few bars-may give

some idea of its character.

(Here was played an extract from 'La Chute de la Maison

Usher'.)

It is my belief that a study of Debussy's unfinished Poe's

operas and of the ideas that they engendered offers an illuminating view of many subsequent musical developments. Not

for nothing was Poe's work the subject of an exhaustive psychoanalytic study, by Marie Bonaparte, with a preface by Freud. 11

The sexual dream visions of Poe's tales, colliding as in a

nightmare, were at the basis of works by several later writers,

among them Villiers de l'Isle Adam's Axel, a scene of which

was also set by Debussy .17

Here it is worth drawing attention to Poe's own ideas, known

to Debussy, on the nature of music. 'I know', Poe writes, 'that

indefiniteness is an element of true music ... a suggested

indefiniteness bringing about a definiteness of vague and

therefore of spiritual effect'. Commenting on this passage

The libretto and musical sketches for La Chute de la Maison Usher arc

published in Debwsy et Edgar Poe, edited by E. Lockspeiser, Paris, 1g62.

19 Marie Bonaparte, The Life and Works of Edgar Allan Poe, translated by

J. Rodkcr, London, 1949.

17 See L. Vallas, Claude Debwsy et son temps, 2nd edition, Paris, 1958.

15

58

DEBUSSY'S CONCEPT 01,. THE DREAM

Edmund Wilson, in his book The Shores of Light writes: 'The

real significance of Poe's short stories does not lie in what they

purport to relate. Many are confessedly dreams; and, as with

dreams. though they seem absurd, their effect on our emotions

is serious, And even those that pretend to the logic and the

exactitude of actual narratives are, nevertheless, also dreams ...

No one understood better than Poe that, in fiction and in

poetry both, it is not what you say that counts, but what you

make the reader feel (he always italicises the word 'effect'); no

one understood better than Poe that the deepest psychological

truth may be rendered through phantasmagoria. Even the

realistic stories of Poe are, in fact, only phantasmagoria of a

more circumstantial kind'. 111 And he concludeswithastatement

that shows at once the lasting appeal of Poe for Debussy: 'He

had elements in him that corresponded with the indefiniteness

of music and the exactitude of mathematics'.

I have dwelt on these literary origins of Debussy's concept of

the dream and you may think that this places rather too much

emphasis on this aspect of the work of Debussy who was, after

all, a musician. In fact, Debussy had no musical antecedents in

France. His friends were almost exclusively literary people, he

had strong literary leanings himself, and he was deeply

involved in the great literary movement that spread from Poe

and Baudelaire to Mallarme and to Marcel Proust and Paul

Valery. He lived, moreover, at a time when, under the impact

in France of Wagner, there was a cross-fertilisation between

the arts. The poets themselves aspired to a state of music, and

so did the Impressionist painters. In their technique they were

always using musical tenns, 'scales of colours' and 'tones'.

Debussy was greatly affected by painting-'! love pictures

almost as much as music', 11 he stated, and in regard to

pictorial representations of the dream there was one painter to

whom Debussy was particularly drawn. This was Turner

whose later works were far more revolutionary and im·

pressionistic than the later properly called Impressionist

painters, though the exact nature of his influence on the

French painters remains ill-defined. Turner is mentioned

11

11

E. Wilson, 'Poe at Home and Abroad', in The Shoru of Light, !\ew York,

J 95!2.

Unpublished letter of February, 19 n to Edgar Vartse.

DEBUSSY'S CONCEPT OF THE DREAM

59

twice in Debussy's correspondence, in 1892 and 1908, '° that is

to say, at times when few French artists, apart from Monet and

Pissarro, had any knowledge of his work. On the second

occasion Debussy refers to Turner in the superlative terms that

he uses elsewhere only for Poe. When working on the Images for

orchestra he writes: 'I am trying to achieve something

different, let us call it reality-what certain foolish people call

"Impressionism", a term used as incorrectly as possible

particularly by art critics who do not hesitate to apply it to

Turner, the greatest creator of mystery in art.' Debussy would

seem to be echoing here the well.known opinion of Ruskin

also mentioned in Debussy's writings. 11 We cannot be sure

which pictures of Turner Debussy had seen, nor where he had

seen them. But our evidence of Turner's influence in France, in

particular his reputation established there by the English art

critic, Philip Hamerton, 11 as a painter of dream visions and of

seascapes shot through with dream memories, allows us at any

rate to draw a parallel between the associations in Debussy's

numerous water pieces and those in the paintings of Turner.

At the opening of this paper I quoted Sir Kenneth Clark's

opinion that Turner's work conveyed in a unique manner the

qualities of a dream. Analysing Turner's technique in his

picture The Snowstorm, Clark suggests that in detail it recalls

the ornamentation and tradition of the arabesque in the work

of the Japanese painter, Hokusai. 'The chaos of a stormy sea',

Clark writes, 'is portrayed as accurately as if it were a bunch of

flowers'.u By a coincidence-and I do not think it can be

more than a coincidence, though it certainly illustrates a

parallel line of thought-the cover chosen by Debussy for the

published score of La Mer consists of a highly decorative

picture by Hokusai of a wave. La Mer in its wonderful sense of

detail has the same quality of the arabesque that we find in the

pictures of Hokusai, the same quality of the 'bunch of flowers'

that we may see in the details of Turner's Snowstorm, But it

also has something of the visionary drama of Turner's seascapes. Debussy uses a sense of the arabesque in the same

disturbing way. I do not think this parallel should be carried

'° Letters to Robert Godct and Jacques Durand.

11

In the unpublished play of Debussy F.E.A. (Frires en Art).

Philip Hamerton, Turner, Pans, 188g. An abridged form of this author's

The Life of J.M. W. Turner, London, 1879.

" Sir Kenneth Clark, op. ed.

11

60

DEBUSSY'S CONCEPT OF THE DREAM

further except to say that in a mind such as that of Debussy, so

receptive to both poetic and visual experiences, original

musical symbols were bound to be created by the ideas or

sights which had impressed him so deeply. These symbols in

La Mer of vortexes and whirlpools, of the gurgling backwash

and of the immensity of enveloping waves are clear enough to

us all.

(Here was played an extract from the third movement of

'La Mer'.)

Such visions have a pictorial appeal but they also contribute,

in the minds of Debussy, Poe and Turner alike, to an awareness

of certain fantasies of the unconscious. The sea is frequently

identified in modern psychology with a mother figure. 'Lamer

notre mere a tous', Debussy declared. u And there have been

many studies of the significance of water in dream poetry,

notably 'L'eau et Les reves' by Gaston Bachelard, 211 in which the

ideas of reflection and movement in water, one of the root

sources of inspiration in Symbolist poetry and Impressionist

painting, are brought to the frontiers of modern psychology.

Let me, in conclusion, quote an impression of Turner's

Snowstorm by Sir Kenneth Clark which may very well be

applied to La Mer and which goes far to helping us to understand the new provinces of the unconscious mind which

Debussy's music had conquered. I have already referred to the

'new knowledge of dreams as the expression of deep intuitions

and buried memories' which, Clark suggests, should be brought

to Turner's work. And he goes on: 'This dream-like condition

reveals itself by the repeated appearance of certain motifs

which are known to be part of the furniture of the unconscious.

One of these is the vortex or whirlpool, which became more

and more the underlying rhythm of his designs .... It is a

dream experience'. 2 • The son of a sailor who in youth had

been destined to be a sailor himself, Debussy was drawn to the

sea not only by what he refers to as his 'countless memories',

but by his imaginative conception of the sea which could not

fail to have been prompted by the seascapes of Turner and also

Letter of 18 June, 1916 to an anonymous corrcspond~t, &uue des Dewc

Mandes, 15 May, 1958.

u Paris, J 96o.

u Sir Kenneth Clark, op. cit.

H

DEBUSSY'S CONCEPT OF THE DREAM

61

by the seascapes of Poe, notably in The Narrative of Arthur

Gordon Pym. The original title of the first movement of La Mer,

Mer belle aux Iles Sanguinaires is in fact the title of a tale by

Camille Mauclair, 17 author of the two principal French

studies on Poe and on Turner. There we have it. As we look

back on the great Symbolist and Impressionist movement,

with its strong musical associations and of which Poe and

Turner were in a sense the godfathers, it was perhaps no

accident that the ideals of this movement, at any rate in its

dream aspects, were ultimately to be realised in the work of

Debussy, a musician.

17

Published in L'Eclw de Pans illustre, '27 February, 1893 .

•