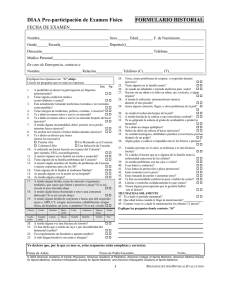

MENOS RIESGO, MÁS PROGRESO 20 CLAVES para PREVENIR LESIONES (basadas en +60 estudios científicos) Creado y editado por Alejandro López Rubio @IBEROFIT TABLA DE CONTENIDOS APARTADOS PÁGINAS 1. FUERZA 6 2. TÉCNICA 7 3. PLANIFICACIÓN 8 4. CALENTAMIENTO 9 5. FLEXIBILIDAD 10 6. RESISTENCIA CARDIO-RESPIRATORIA 11 7. ESTABILIDAD CENTRAL 12 8. DESCOMPENSACIONES MUSCULARES 13 9. COORDINACIÓN 14 10. PROPIOCEPCIÓN 15 11. FOCO ATENCIONAL 17 12. FATIGA MENTAL 18 13. ALIMENTACIÓN 20 14. HIDRATACIÓN 21 15. ESTILO DE VIDA 23 16. DESCANSO 24 17. DAÑO MUSCULAR DE APARICIÓN TARDÍA 25 18. ÍNDICE DE MASA CORPORAL (IMC) 26 19. HIGIENE POSTURAL 27 20. MATERIAL DEPORTIVO 29 @IBEROFIT 2 TÉRMINOS CLAVE (1, 2) Lesión: es un daño o traumatismo que produce alteraciones estructurales o condicionales y/o dolor y que interfiere en el proceso del entrenamiento. Orígenes de las lesiones - Cargas aisladas: carga intensa única que excede la capacidad de tensión máxima que es capaz de soportar el tejido. - Cargas repetitivas: conjunto de cargas menos intensas pero que se van acumulando con el tiempo. Factores de riesgo de lesión - Factores intrínsecos: edad, sexo, composición corporal, salud, condición física, anatomía, técnica... - Factores extrínsecos: factor humano, factor material y de equipamiento, factor ambiental... A continuación, vas a descubrir 20 factores de riesgo clave para prevenir lesiones deportivas y que puedes controlar o entrenar... @IBEROFIT 4 FACTORES DE RIESGO RELACIONADOS CON EL - ENTRENAMIENTO FUERZA TÉCNICA PLANIFICACIÓN CALENTAMIENTO FLEXIBILIDAD RESISTENCIA CARDIO-RESPIRATORIA ESTABILIDAD CENTRAL DESCOMPENSACIONES MUSCULARES COORDINACIÓN PROPIOCEPCIÓN @IBEROFIT 5 FUERZA (14-17) La fuerza es la capacidad física más ligada a la prevención y rehabilitación de lesiones. Está demostrado que disminuye la incidencia de lesiones en el entrenamiento y en el deporte. Se ha evidenciado que un desequilibrio de fuerza muscular entre dos lados del cuerpo supone más probabilidades de lesionarse en el músculo más débil. No sólo ayuda el nivel de fuerza por sí mismo, sino también las propiedades funcionales y propiedades fijadoras que son necesarias para proteger a las articulaciones del cuerpo. ¡ENTRENA LA FUERZA! (NO ES UNA OPCIÓN) @IBEROFIT 6 TÉCNICA @IBEROFIT (6, 20, 30 Y 31) 7 PLANIFICACIÓN (3-11) Planificación global: en la prevención de lesiones interviene el trabajo de deportistas, entrenadores, fisios, psicólogos, médicos, nutricionistas... Por tanto, se debe establecer una planificación integral. Intensidad: tanto el entrenamiento en rangos de fuerza como de hipertrofia van a ayudar a prevenir lesiones si se regula y maneja bien la carga y se descana lo necesario para recuperarse adecuadamente. MUY RECOMENDADO PARA "FRIKIS" DE LAS LESIONES Volumen de entrenamiento: si la carga semanal aumenta más del 15% con respecto a la anterior, el riesgo de lesión aumenta un 20%. Cambios repentinos de planes de entrenamiento: los cambios bruscos pueden elevar el riesgo de sufrir lesiones Control de las intensidad: el RPE (escala subjetiva de percepción del esfuerzo) permite ver señales de riesgo de lesión si hay una gran diferencia entre el RPE planificado y el ejecutado. Imagen extraída de https://www.com.fisiosaludable.com/conceptos/241escala-de-borg @IBEROFIT 8 CALENTAMIENTO (12, 13) 2 RAZONES de peso para RECORDAR SIEMPRE CALENTAR: Un calentamiento inadecuado e insuficiente va a hacer que el músculo sea menos elástico y que haya una peor coordinación neuromuscular. Los deportistas que peor calientan tienen asociado un mayor riesgo de lesionarse al entrenar o competir. *Imagen extraída de mis publicaciones de instagram* @IBEROFIT 9 il m p o nat r FLEXIBILIDAD d r o e t r i esgo c a f n u m s e uy i ad d (19-25) et ib ix e l f a L La flexibilidad es la capacidad de un músculo para alargarse y permitir que la articulación o articulaciones se muevan a través de un rango óptimo de movimiento (ROM). La flexibilidad es específica de cada articulación, acción muscular, sexo e incluso deporte. Una mejor flexibilidad se relaciona con un menor riesgo de lesión. Mejorar la dorsiflexión activa del tobillo reduce en un 37% la probabilidad de sufrir una lesión en el LCA de la rodilla. *Imagen extraída de mis publicaciones de instagram* @IBEROFIT 10 RESISTENCIA C-R (44-46) MENOR CAPACIDAD AERÓBICA APARICIÓN PRECOZ DE FATIGA AGUDA SE REDUCE EL EFECTO PROTECTOR ARTICULAR DE LA MUSCULATURA DISMINUYE LA CAPACIDAD DE COORDINACIÓN Y DE TOMA DE DECISIONES AUMENTA EL RIESGO DE LESIÓN @IBEROFIT 11 (26) ESTABILIDAD CENTRAL SEGURO QUE HAS OÍDO MILES DE VECES EL TÉRMINO "CORE" PERO EL TÉRMINO DE "ESTABILIDAD CENTRAL" ES MENOS COMÚN Aunque no lo creas, la realidad es que ambos términos dependen el uno del otro y son prácticamente sinónimos. El "core" se puede ver desde un prisma cuantitativo (conjunto de músculos que conforma el núcleo central del cuerpo). Y la "estabilidad central" tiene un enfoque más cualitativo (son las habilidades y beneficios que aporta el "core" a nuestro rendimiento físico y a nuestra salud) EQUILIBRIO POSTURA *Imagen extraída de (26) Huxell & Anderson (2013)* RECUPERACIÓN DE LESIONES AMOTRIGUACIÓN IMPACTOS *Imagen extraída de mis publicaciones de instagram* @IBEROFIT 12 (47-55) DESCOMPENSACIONES Suele haber descompensaciones musculares debido a la dominancia lateral innata de una extremidad sobre otra y a la especialización lateral. Un ratio de fuerza desequilibrado entre isquios y cuádriceps es un factor de riesgo de lesiones en el tren inferior. Los desequilibrios de fuerza no corregidos hacen que exista entre 4 y 5 veces más probabilidad de lesionarse. Si el desequilbrio de fuerza es superior 15%, el riesgo de sufrir lesiones en la extremidad más débil es 2,6 veces mayor. *Imagen extraída de mis publicaciones de instagram* @IBEROFIT 13 COORDINACIÓN PEOR COORDINACIÓN NEUROMUSCULAR (64) MAYOR RIESGO DE LESIONARSE ¿CÓMO MEJORAR LA COORDINACIÓN? EJERCICIOS DE FUERZA ESCALERAS DE AGILIDAD SALTOS EN CRUZ VALLAS, CONOS Y PICAS @IBEROFIT 14 PROPIOCEPCIÓN PEOR CAPACIDAD PROPIOCEPTIVA (59-61) MAYOR RIESGO DE LESIONARSE La PROPIOCEPCIÓN es la capacidad para sentir dónde se ubican las partes de tu cuerpo en el espacio y controlar tus músculos. Se mejora entrenando: La FUERZA, La COORDINACIÓN, La VELOCIDAD DE REACCIÓN y El EQUILIBRIO (estático y dinámico) ES NECESARIO ENTRENAR A NIVEL DE TOBILLO, RODILLA, CADERA Y TRONCO ¡NO ES NECESARIO ENTRENAR CON SUPERFICIES INESTABLES! @IBEROFIT 15 FACTORES DE RIESGO RELACIONADOS CON LA - PSICOLOGÍA FOCO ATENCIONAL FATIGA MENTAL @IBEROFIT 16 FOCO ATENCIONAL (32-36) Cuando tenemos inmovilizado por un tiempo una parte del cuerpo debido a una lesión, podemos suavizar o detener las pérdidas de fuerza y de control motor mediante una estrategia llamada "mental imagery" (es una estrategia de visualización mental). Se logra disminuir la inhibición cortical que se da en esos periodos de inactividad física prolongados. La inhibición cortical aumenta durante la inactividad y es un importante factor neurofisiológico en la regulación de la capacidad de generar fuerza. @IBEROFIT 17 (37-43) FATIGA MENTAL La fatiga mental se asocia a peores niveles de rendimiento, técnica y toma de decisiones @IBEROFIT 18 FACTORES DE RIESGO RELACIONADOS CON LA - NUTRICIÓN ALIMENTACIÓN HIDRATACIÓN @IBEROFIT 19 ALIMENTACIÓN (3 y 20) FACTORES QUE AUMENTAN EL RIESGO DE SUFRIR FRACTURAS POR ESTRÉS DÉFICIT DE CALCIO TRASTORNOS ALIMENTICIOS DÉFICIT DE VITAMINA D ES VITAL LA VALORACIÓN DE MÉDICOS, PSICÓLOGOS Y NUTRICIONISTAS @IBEROFIT 20 HIDRATACIÓN @IBEROFIT (56) 21 FACTORES DE RIESGO RELACIONADOS CON LA - SALUD ESTILO DE VIDA DESCANSO DAÑO MUSCULAR DE APARICIÓN TARDÍA (DOMS) ÍNDICE DE MASA CORPORAL HIGIENE POSTURAL @IBEROFIT 22 ESTILO DE VIDA (58) ESTAR SENTADO DURANTE TIEMPOS PROLONGADOS PROVOCA DESACONDICIONAMIENTO FÍSICO Y FATIGA MUSCULAR PRECOZ ESTILOS DE VIDA SEDENTARIOS ESTÁN ASOCIADOS A UNA DISMINUCIÓN DE LA MASA MUSCULAR Y VASCULARIZACIÓN, ASÍ COMO A UNA MENOR CAPACIDAD ELÁSTICA Y MAYOR RIGIDEZ MUSCULAR HAY UN MAYOR RIESGO DE DESARROLLAR OSTEOPOROSIS. AL NO REALIZAR ACTIVIDADES ANABÓLICAS, LA PRODUCCIÓN DE GH Y DE IGF-1 NO SE VE ESTIMULADA Y SUS NIVELES DECRECEN EL SUEÑO Y EL DESCANSO ES INADECUADO AL LLEVAR UN ESTILO DE VIDA SEDENTARIO @IBEROFIT 23 DESCANSO (57) ¡OJOOOO! DORMIR 6 HORAS O MENOS SE ASOCIA A LESIONES RELACIONADAS CON LA FATIGA SE RECOMIENDA DORMIR COMO MÍNIMO 7 HORAS PARA REDUCIR EL RIESGO DE LESIONARSE +7 HORAS @IBEROFIT 24 DOMS (62) LOS SÍNTOMAS SUELEN SER DOLOR EN EL MOVIMIENTO, DEBILIDAD Y UNA SENSACIÓN DE RIGIDEZ E HINCHAZÓN DE LOS MÚSCULOS QUE SE PRODUCE ESTOS SÍNTOMAS SUELEN APARECER O INTENSIFICARSE 1-2 DÍAS DESPUÉS DEL ENTRENAMIENTO Y PUEDEN dolor TRAS REALIZAR NORMALMENTE UN INTENSO TRABAJO EXCÉNTRICO. LLEGAR A DURAR HASTA 5-7 DÍAS tiempo LAS CONTRACCIONES EXCÉNTRICAS PROVOCAN MICRO-LESIONES EN EL TEJIDO MUSCULAR CON MUCHA MAYOR FRECUENCIA Y SEVERIDAD QUE OTROS TIPOS DE CONTRACCIÓNES EL DOMS PUEDE REDUCIR EL RENDIMIENTO Y AUMENTAR EL RIESGO DE LESIÓN. AL SUFRIR DOMS SE EXPERIMENTA UNA REDUCCIÓN EN EL RANGO ÓPTIMO DE MOVIMIENTO DE LAS ARTICULACIONES, EN LA AMORTIGUACIÓN DE IMPACTOS Y DE FUERZAS DE TORSIÓN TAMBIÉN SE VE ALTERADA LA CAPACIDAD PARA RECLUTAR LAS FIBRAS MUSCULARES POR LO QUE EL ESTRÉS AUMENTA EN LOS LIGAMENTOS Y TENDONES MEDIDAS PREVENTIVAS MASAJES CALENTAR FOAM ROLLER CAFEÍNA @IBEROFIT PROTEÍNA PRE-ENTRENO INMERSIÓN EN AGUA FRÍA 25 IMC (18) "Dejemos que el gato-ayudante analice esta revisión sistemática y extraiga los puntos clave" ESTO ES LO QUE HA VISTO EL GATO... La gran mayoría de estudios correlacionan un mayor IMC con un aumento de la incidencia de lesiones. Las personas con mayor IMC sufren una carga mayor en los ligamentos y esto aumenta el riesgo. A mayor IMC, menor capacidad articular para soportar cambios de dirección y para estabilizarse. @IBEROFIT 26 HIGIENE POSTURAL (27-29) HAY CONTROVERSIA SOBRE SI LA POSTURA PUEDE CONSIDERARSE UN FACTOR RELEVANTE POR SÍ MISMO PERO PODRÍA SER DETERMINANTE SI ENTRAN EN JUEGO A LA VEZ OTROS FACTORES DE RIESGO @IBEROFIT 27 FACTORES DE RIESGO RELACIONADOS CON EL - MATERIAL MATERIAL DEPORTIVO @IBEROFIT 28 (4 y 63) MATERIAL DEPORTIVO @IBEROFIT 29 MUCHAS GRACIAS POR LLEGAR HASTA AQUÍ :) Puedes ver mucho más en mi instagram @iberofit AVISO: el hecho de aplicar todas las medidas preventivas no elimina totalmente el riesgo de sufrir lesiones deportivas, pero sí que lo reduce bastante. Ante la mínima sospecha de estar lesionado/a o estar empezando a notar síntomas de lesión deberías acudir a especialistas que te valoren y supervisen de manera individualizada el entrenamiento, la rehabilitación fisioterapéutica y la nutrición. askiberofit@gmail.com @IBEROFIT BIBLIOGRAFÍA (1) Romero, D., & Tous, J. (2010). Prevención de lesiones en el deporte: claves para un rendimiento deportivo. Madrid. Panamericana. (2) Bahr, R., & Holme, I. (2003). Risk factors for sports injuries. A methodological approach. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 37, 384392. (3) Butragueño, J. (2015). Incidencia, prevalencia y severidad de las lesiones deportivas en tres programas de entrenamiento para la pérdida de peso. Tesis Doctoral. Universidad Politécnica de Madrid. (4) Dvorak, J. & Junge, A. (2000). Football injuries and physical symptoms. A review of the literature. American Journal of Sports Medicine. 28, 3-9. (5) Gabbet, T.J. (2016). The training injury prevention paradox: should ahtletes be training smarter and harder?. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 50, 273-289. (6) Hans-Wilhelm, M., Haensel, L., Mithoefer, K. et al. (2012). Terminología y clasificación de las lesiones musculares en el deporte: La declaración de Consenso Múnich. British Journal of Sports Medicine. (7) Orchard, J.W. (2001). Intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors for muscle strains in Australian Football. Amercian Journal of Sports Medicine. 29(3), 300-303. (8) Petersen, J., & Holmich, P. (2005). Evidence based of hamstring injuries in sport. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 9, 319-323. (9) Van Mechelen, W., Hlobil, H., & Kemper, H.C. (1992). Incidence, severity, aethiology and preventiva of sports injuries. A review of concepts. 14(2), 82-99. (10) Noya, J., & Sillero, M. (2012). Epidemiología de las lesiones en el fúbtol profesional español en la temporada 2008-2009. Archivos de medicina del dpeorte. 29 (150), 750-766. (11) Soligard, T., et al. (2016). How much is too much? (Part 1) International Olympic Committee consensus statement on load in sport and risk of injury. British journal of sports medicine, 50(17), 1030–1041. (12) Bahr, R., & Engebretsen, L. (2009). Sports Injury Prevention. Willey-Blackwell, Oxford, Reino Unido. (13) Fradkin, A. J., Gabbe, B. J., & Cameron, P. A. (2006). Does warming up prevent injury in sport? The evidence from randomised controlled trials?. Journal of science and medicine in sport, 9(3), 214–220. (14) Parkkari, J., Urho, M., Kujala, U., & Kannus, P. (2001). Is it possible to prevent sports injuries? Review of controlled clinical trials and recommendations for future work. Sports Medicine, 31(14), 985-995. (15) Thacker, S.B., Stroup, D.F., Branche, C,M., Gilchrist, J., Goddman, R.A., & Porter Kelling, E. (2003). Prevention of knee injuries un sports: A systematic review of the literature. Journal Sports Medicine Physicial Fitness. 43(2): 165-179. (16) Ekstrand, J., & Gillquist, J. (1983). The avoidability of soccer injuries. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 4, 1124-1128. (17) Bahr, R., & Reeser, J. (2003). Injuries among world-class professional beach voleyball players. The Federation Internationale de Volleyball. Beach volleyball injury study. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 31, 119-125. (18) Amoako, A. O., Nassim, A., & Keller, C. (2017). Body Mass Index as a Predictor of Injuries in Athletics. Current sports medicine reports, 16(4), 256–262. (19) Witvrouw, E., Asselman, P., D'have, T., & Cambier, D. (2003). Muscle flexibility as a risk factor for developping muscle injuries in male professional soccer players. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 31(1), 41-46. (20) Bisciotti, G. N., & Eirale, C. (2013). Muscle Injuries in Sport Medicine. InTech. (21) Zakas, A., Vergou, A., Zakas, N., Grammatikopoulou, M.G., & Grammatikopoulou, G.T. (2002). Handball match effect on the flexibility of junior handball players. Journal of Human Movement Studies, 43, 321-330. (22) Kibler, W.B., & Chandler, T.J. (2003). Range of movement in junior tennis player participating in an injury risk modification program. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 6(1), 51-62. (23) Riewald, S. (2004). Stretching the limits of our knowledge on Stretching. Strenght and Conditioning Journal, 26(5), 58-59. (24) Witvrouw, E., Mahieu, N., Roosen, P., & McNair, P. (2007). The role of stretching in tendon injuries. British journal of sports medicine, 41(4), 224–226. (25) Amraee, D., Alizadeh, M. H., Minoonejhad, H., Razi, M., & Amraee, G. H. (2017). Predictor factors for lower extremity malalignment and non-contact anterior cruciate ligament injuries in male athletes. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy : official journal of the ESSKA, 25(5), 1625–1631. (26) Huxel Bliven, K. C., & Anderson, B. E. (2013). Core stability training for injury prevention. Sports health, 5(6), 514–522. (27) Watson AW. Sports injuries in footballers related to defects of posture and body mechanics. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness. 1995 Dec;35(4):289-294. @IBEROFIT BIBLIOGRAFÍA (28) Greenfield, B., Catlin, P. A., Coats, P. W., Green, E., McDonald, J. J., & North, C. (1995). Posture in patients with shoulder overuse injuries and healthy individuals. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy, 21(5), 287–295. (29) Neal, B. S., Griffiths, I. B., Dowling, G. J., Murley, G. S., Munteanu, S. E., Franettovich Smith, M. M., Collins, N. J., & Barton, C. J. (2014). Foot posture as a risk factor for lower limb overuse injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of foot and ankle research, 7(1), 55. (30) Safran, M. R., Garrett, W. E., Seaber, A. V., Glisson, R. R., & Ribbeck, B. M. (1988). The role of warmup in muscular injury prevention. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 16(2), 123–129. (31) Woods, K., Bishop, P., & Jones, E. (2007). Warm-up and stretching in the prevention of muscular injury. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 37(12), 1089–1099. (32) Frenkel, M. O., Herzig, D. S., Gebhard, F., Mayer, J., Becker, C., & Einsiedel, T. (2014). Mental practice maintains range of motion despite forearm immobilization: a pilot study in healthy persons. Journal of rehabilitation medicine, 46(3), 225–232. (33) Clark, B. C., Mahato, N. K., Nakazawa, M., Law, T. D., & Thomas, J. S. (2014). The power of the mind: the cortex as a critical determinant of muscle strength/weakness. Journal of neurophysiology, 112(12), 3219–3226. (34) Rio, E., Kidgell, D., Moseley, G. L., Gaida, J., Docking, S., Purdam, C., & Cook, J. (2016). Tendon neuroplastic training: changing the way we think about tendon rehabilitation: a narrative review. British journal of sports medicine, 50(4), 209–215. (35) Gokeler, A., Benjaminse, A., Welling, W., Alferink, M., Eppinga, P., & Otten, B. (2015). The effects of attentional focus on jump performance and knee joint kinematics in patients after ACL reconstruction. Physical therapy in sport : official journal of the Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Sports Medicine, 16(2), 114–120. (36) Almonroeder, T. G., Jayawickrema, J., Richardson, C. T., & Mercker, K. L. (2020). THE INFLUENCE OF ATTENTIONAL FOCUS ON LANDING STIFFNESS IN FEMALE ATHLETES: A CROSS-SECTIONAL STUDY. International journal of sports physical therapy, 15(4), 510– 518. (37) Borotikar, B. S., Newcomer, R., Koppes, R., & McLean, S. G. (2008). Combined effects of fatigue and decision making on female lower limb landing postures: central and peripheral contributions to ACL injury risk. Clinical biomechanics (Bristol, Avon), 23(1), 81–92. (38) Wiese-Bjornstal D. M. (2010). Psychology and socioculture affect injury risk, response, and recovery in high-intensity athletes: a consensus statement. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 20 Suppl 2, 103–111. (39) Verschueren, J., et al. (2020). Does Acute Fatigue Negatively Affect Intrinsic Risk Factors of the Lower Extremity Injury Risk Profile? A Systematic and Critical Review. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 50(4), 767–784. (40) Martin K, Meeusen R, Thompson KG, Keegan R, and Rattray B. Mental fatigue impairs endurance performance: A physiological explanation. Sports medicine (Auckland, NZ): 1-11, 2018. (41) Russell S, Jenkins D, Smith M, Halson S, and Kelly V. The application of mental fatigue research to elite team sport performance: New perspectives. J Sci Med Sport 22: 723-728, 2019. (42) Greco G, Tambolini R, Ambruosi P, and Fischetti F. Negative effects of smartphone use on physical and technical performance of young footballers. Journal of Physical Education and Sport 17: 2495-2501, 2017. (43) Woods, C., Hawkins, R. D., Maltby, S., Hulse, M., Thomas, A., Hodson, A., & Football Association Medical Research Programme (2004). The Football Association Medical Research Programme: an audit of injuries in professional football--analysis of hamstring injuries. British journal of sports medicine, 38(1), 36–41. (43) Bell, N., Mangione, T., Hemenway, D., Amoroso, P., & Jones, B. (2000). High injury rates among female army trainees: a function of gender? American journal of preventive medicine, 18 3 Suppl, 141-6. (44) Hopper, D. M., Hopper, J. L., & Elliott, B. C. (1995). Do selected kinanthropometric and performance variables predict injuries in female netball players?. Journal of sports sciences, 13(3), 213–222. (45) Jones, B. H., Bovee, M. W., Harris, J. M., 3rd, & Cowan, D. N. (1993). Intrinsic risk factors for exercise-related injuries among male and female army trainees. The American journal of sports medicine, 21(5), 705–710. (46) Knapik, J. J., Sharp, M. A., Canham-Chervak, M., Hauret, K., Patton, J. F., & Jones, B. H. (2001). Risk factors for training-related injuries among men and women in basic combat training. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 33(6), 946–954. (47) Aagaard, P., Simonsen, E. B., Trolle, M., Bangsbo, J., & Klausen, K. (1995). Isokinetic hamstring/quadriceps strength ratio: influence from joint angular velocity, gravity correction and contraction mode. Acta physiologica Scandinavica, 154(4), 421–427. (48) Baumhauer, J. F., Alosa, D. M., Renström, A. F., Trevino, S., & Beynnon, B. (1995). A prospective study of ankle injury risk factors. The American journal of sports medicine, 23(5), 564–570. (49) Chomiak J, Junge A, Peterson L, Dvorak J. Severe injuries in football players. Influencing factors. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(5 Suppl):S58-68. (50) Ciacci, S., Di Michele, R., Fantozzi, S., & Merni, F. (2013). Assessment of Kinematic Asymmetry for Reduction of Hamstring Injury Risk, International Journal of Athletic Therapy and Training, 18(6), 18-23. @IBEROFIT BIBLIOGRAFÍA (51) Croisier, J. L., Ganteaume, S., Binet, J., Genty, M., & Ferret, J. M. (2008). Strength imbalances and prevention of hamstring injury in professional soccer players: a prospective study. The American journal of sports medicine, 36(8), 1469–1475. (52) Engebretsen, A. H., Myklebust, G., Holme, I., Engebretsen, L., & Bahr, R. (2010). Intrinsic risk factors for hamstring injuries among male soccer players: a prospective cohort study. The American journal of sports medicine, 38(6), 1147–1153. (53) Garrido, J., Huérfano, Y. & Piñeros, A. (2002). Imbalance muscular como factor de riesgo para lesiones deportivas de rodilla en futbolistas profesionales de Bogotá. Bab. Fisioterapia. (54) Naclerio, F. (2008). Entrenamiento de Fuerza en la Práctica Deportiva: Zonas de Entrenamiento y Ejercicios de Prevención. PubliCE. 0. (55) Söderman, K., Alfredson, H., Pietilä, T., & Werner, S. (2001). Risk factors for leg injuries in female soccer players: a prospective investigation during one out-door season. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy : official journal of the ESSKA, 9(5), 313–321. (56) Thomas, D. T., Erdman, K. A., & Burke, L. M. (2016). Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Dietitians of Canada, and the American College of Sports Medicine: Nutrition and Athletic Performance. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 116(3), 501–528. (57) Luke, A., Lazaro, R. M., Bergeron, M. F., Keyser, L., Benjamin, H., Brenner, J., d'Hemecourt, P., Grady, M., Philpott, J., & Smith, A. (2011). Sports-related injuries in youth athletes: is overscheduling a risk factor?. Clinical journal of sport medicine : official journal of the Canadian Academy of Sport Medicine, 21(4), 307–314. (58) Lurati A. R. (2018). Health Issues and Injury Risks Associated With Prolonged Sitting and Sedentary Lifestyles. Workplace health & safety, 66(6), 285–290. (59) Riva, D., Bianchi, R., Rocca, F., & Mamo, C. (2016). Proprioceptive Training and Injury Prevention in a Professional Men's Basketball Team: A Six-Year Prospective Study. Journal of strength and conditioning research, 30(2), 461–475. (60) Verhagen, E., van der Beek, A., Twisk, J., Bouter, L., Bahr, R., & van Mechelen, W. (2004). The effect of a proprioceptive balance board training program for the prevention of ankle sprains: a prospective controlled trial. The American journal of sports medicine, 32(6), 1385–1393. 61) Söderman, K., Alfredson, H., Pietilä, T., & Werner, S. (2001). Risk factors for leg injuries in female soccer players: a prospective investigation during one out-door season. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy : official journal of the ESSKA, 9(5), 313–321. (62) Cheung, K., Hume, P., & Maxwell, L. (2003). Delayed onset muscle soreness : treatment strategies and performance factors. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 33(2), 145–164. (63) Jaffet, R., & López. R. (1996). Vendajes, tobilleras y equipamiento protector. Badalona. (64) Hutchinson, M. R., & Ireland, M. L. (2003). Overuse and throwing injuries in the skeletally immature athlete. Instructional course lectures, 52, 25–36. @IBEROFIT