UNIT 10: WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND COMPOUNDS

UNIT 10:

WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND

COMPOUNDS

Outline

The word as a linguistic sign. ............................................................................................. 3

1.

2.

a)

Definition for “word”. ....................................................................................................... 3

b)

The word as a linguistic sign. ............................................................................................ 3

c)

Word analysis .................................................................................................................... 4

Lexical creativity ................................................................................................................. 6

Word formation or neologism ................................................................................................... 6

COMPOUNDING ................................................................................................................. 6

AFFIXATION ....................................................................................................................... 8

CLIPPING ........................................................................................................................... 16

CONVERSION ................................................................................................................... 17

BACK-FORMATION ......................................................................................................... 18

REDUPLICATIVES ........................................................................................................... 18

BLENDING ........................................................................................................................ 18

ACRONYMS ...................................................................................................................... 19

EPONYMY ......................................................................................................................... 20

OTHER TYPES OF ABBREVIATIONS: .......................................................................... 20

FACETIOUS FORMS: ....................................................................................................... 20

BAGONIZING .................................................................................................................... 22

BROADENING .................................................................................................................. 23

1.

Socio-cultural factors .................................................................................................. 23

2.

Psychological Factors .................................................................................................. 24

Examples of broadening .......................................................................................................... 24

1.

Business....................................................................................................................... 24

2.

Cool ............................................................................................................................. 24

3.

Demagogue ................................................................................................................. 24

Broadening - key takeaways ................................................................................................... 24

NARROWING .................................................................................................................... 25

What causes narrowing?.......................................................................................................... 25

Sociocultural causes ............................................................................................................ 25

1

UNIT 10: WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND COMPOUNDS

Psychological Causes .......................................................................................................... 26

Narrowing - key takeaways ..................................................................................................... 26

3.

False Friends ...................................................................................................................... 27

Metonymy ......................................................................................................................... 29

Examples of metonymy: a recap ......................................................................................... 30

Similes ............................................................................................................................... 31

Personification ................................................................................................................... 31

Idioms ................................................................................................................................ 32

Synecdoque........................................................................................................................ 33

Oxymoron ......................................................................................................................... 35

2

UNIT 10: WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND COMPOUNDS

1. The word as a linguistic sign.

a) Definition for “word”.

Several definitions have been given to the linguistic term “word” and not all of

them have been satisfactory. One of the most accepted, and, at the same time, clearest

definitions is the one given by Bloomfield: “the word is the minimum free form of a

language”. Nevertheless, many linguists say that in a communicative act, the sentence

is the minimum free linguistic form in communication, and the word is its minimal

version. In this case, we would have a sentence consisting of one single word.

b) The word as a linguistic sign.

What do we mean when we say that the word is a linguistic sign? First of all, we

have to regard the language as a communication system where we associate the

“message”, that is, the meaning or ideas we have in our minds, with a set of symbols,

that is to say, the representation of these ideas in the form of words, either written or

spoken.

If we take this into account, we can consider the word as an entity made up of:

a. Signifier, that is, the external form

b. Signified, that is, the meaning of that word

Saussure used the term “sign” in this sense to refer to a linguistic entity, consisting

of signifier and signified. Nevertheless, linguists nowadays prefer to use the term

“sign” to refer only to the signifier. For Saussure, the relationship between both is

symbolic, since words are labels for concepts. The relationship is arbitrary, as there is

no logical, intrinsic or natural relation between a particular acoustic sound and a

concept. For this reason we refer to the same concept with different acoustic sounds in

different languages. Hence, the meaning of any word or sign is derived from its

existence within a network of related signs called SEMANTIC FIELD. For Saussure,

everything in the system of language is based on the relations that can occur between

the units in the system and on relations of different signs.

3

UNIT 10: WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND COMPOUNDS

Each language has a word order structure. Apart from the syntagmatic relations,

there are other relationships that exist outside the discourse: PARADIGMATIC or

ASSOCIATIVE relationships. For instance, there is a paradigmatic relationship

between “he” and the rest of the pronouns.

This view of the word expressed by Saussure has been criticised, and the word is

seen by some linguists not as an entity, made up of signifier and signified, but as a

triangle made up of three elements:

THOUGHT or REFERENCE

Symbol - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -- - - - - - - - - - - - - - referent

Signifier

signified

(sound, word, image)

(mental concept)

c) Word analysis

A word can analysed from different points of view, as it can be regarded as the

following:

An orthographic entity:

A word can be regarded as being made up of different graphic signs with space

around them, that is to say, letters. In some cases the word as an orthographic entity

has different versions. For example, the word colour in British English is spelt color

in American English.

4

UNIT 10: WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND COMPOUNDS

A phonological entity

The word is regarded in terms of sounds, subject to stress, rhythm, etc. This

phonological entity has nothing to do with the orthographic one, and words or groups

of words that are spelt in a completely different manner can be pronounced in the

same way. If I say /ə ˈnəʊʃən /, we do not know whether I have said “a notion” or “an

ocean”, and only the context can clarify this.

A morphological entity

In this case, the word is regarded as being made up of morphemes, that is to say,

the minimal unit having meaning in language. For example, the word “unbearable”

can be divided into three morphemes: un-bear-able.

A grammatical entity

A word can also be analysed regarding the function it has. In this case, words are

divided into two groups:

lexical words: they are those words which have a full meaning and refer to

actions, things or states. The classes of words which belong to this group are nouns,

verbs, adjectives and adverbs.

Grammatical words: they are those words which only have a linking function,

for example, prepositions, conjunctions, articles, determiners, etc.

A lexicographical entity

This is the way in which a word is presented in dictionaries. For example,

if we look up the word “did” in the dictionary, it will be made a reference to “do”. For

this reason, the forms “do, does, did, done, doing” form a lexicographical entity,

meaning that they belong to the same entry in the dictionary.

A Semantic entity

The word, irrespective of its external form or component parts, is primarily a

carrier of meaning.

At word level, semantics explores the relationship which words have with each

other within the language as a whole. The meaning which a word has due to its place

in the linguistic system constitutes its sense.

The Common Core

The diagram used by the first editor of the OED, James Murray, in the section

called “General Explanations”, which preceded volume 1 (1888): “the English

vocabulary contains a nucleus or central mass of many thousand words whose “anglicity”

is unquestioned; some of them only literary, some of them only colloquial; the great

majority at once literary and colloquial. They are the common words of the language).”

5

UNIT 10: WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND COMPOUNDS

2.

Lexical creativity

It is clear that language is not static and new words are introduced every day; by

means of the mass media they then become familiar to many people in a short period of

time. This lexical creativity is achieved by means of three mechanisms: word formation,

conversion and semantic transfer.

Word formation or neologism

According to Bauer (1983), there are different ways of word formation in English:

compounding, affixation (prefixation and suffixation), clipping, conversion,

backformation, blending, acronyms and eponymy.

COMPOUNDING

A compound is a unit of vocabulary which consists of more than one lexical stem.

On the surface, there appear to be two (or more) lexemes present, but in fact the parts are

functioning as a single item, which has its own meaning and grammar. So, flower-pot

does not refer to a flower and a pot, but to a single object. It is pronounced as a unit, with

a single main stress, and it is used grammatically as a unit- its plural, for example, is

flower-pots.

The unity of flower-pot is also signalled by the orthography but this is not a

foolproof criterion. If the two parts are linked by a hyphen as here, or are printed without

a space (“solid”), as in flowerpot, then there is no difficulty. But the form flower pot will

also be found, and in such cases, to be sure we have a compound (and not just a sequence

of two independent words), we need to look carefully at the meaning of the sequence and

6

UNIT 10: WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND COMPOUNDS

the way it is grammatically used. This question turns up especially in American English,

which uses fewer hyphens than does British English.

Compounds are most readily classified into types based on the kind of

grammatical meaning they represent. Earthquake, for example, can be paraphrased as

“the earth quakes”, and the relation of earth to quake is that of subject to verb. Similarly,

a crybaby is also subject + verb (“the baby cries”), despite its back-to-front appearance.

Scarecrow is verb + object (“scares crow”). Some involve slightly trickier grammatical

relations, such as playgoer, windmill, goldfish and homesick.

There is an interesting formation in which one of the elements does not occur as

a separate word. These forms are usually classical in origin, and are linked to the other

element of the compound by a linking vowel, usually –o- , but sometimes –a- and –i-.

They are traditionally found in the domains of science and scholarship, but in recent years

some have become productive in everyday contexts too, especially in advertising and

commerce.

First element:

Agri- - culture, -business

Bio- -data, -technology

7

UNIT 10: WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND COMPOUNDS

Micro- -chip, -electronics

Euro- -money, -feebleness

Psycho- -logy, -analysis

Techno- -phobia, -stress

Second element

-aholic work-, shop-, comput-athon mar-, swim-, read-matic coffee-, wash-o.rama sports-a-, plant-o-

Such forms might well be analysed as affixes, but for the fact that their meaning

is much more like that of an element in a compound. Euromoney, for example, means

“European money”; biodata means “biological data”; swimathon means “swimming

marathon”.

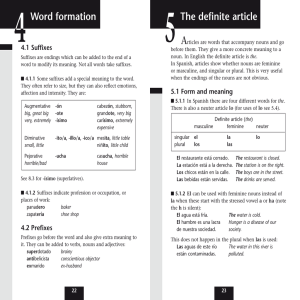

AFFIXATION

Not all affixes have a strong creative potential. OE <-th> warmth, depth, length,

width, sixth is hardly every used to create new words- though zeroth and coolth are

interesting exceptions.

<-ness> is one of the most prolific ones.

Newly-coined ones include –friendly. Sexism brought a host of other –isms, such

as weightism, heightism, ageism. Political correctness introduced –challenged in several

areas. Rambo-based coinages included Ramboesque and Ramboistic. Band-aid gave rise

to Sport-aid and nurse-aid.

8

UNIT 10: WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND COMPOUNDS

Infixes

English has no system of infixes, but people do from time to time coin words into

which other forms have been inserted. This happens quite commonly while swearing or

being emphatic, as in absobloominglutely and kangabloodyroo.

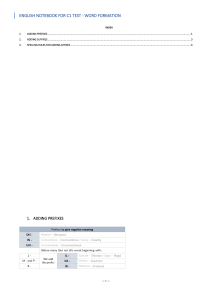

Prefixes

There are 57 varieties of prefixes

NEGATIVE PREFIXES

AAN- (especially before vowels), “lacking in,”, “lacking of”, combines with

adjectives, as in amoral, asexual, anhydrous and in some nouns, as in anarchy.

DIS- “the converse of”, combines with open-class items, including verbs:

disobey, disloyal, disorder, diuse, discontent.

9

UNIT 10: WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND COMPOUNDS

IN- (IL-, IR-, IM-) “the converse of”, combines with adjectives of French and

Latin origin. Incomplete, irregular, illegal, impossible.

NON- combines, usually hyphenated, with nouns, adjectives, and open-class

adverbs: non-smoker, non-perishable, non-trivially.

UN- “the converse of”, combines fairly freely with adjectives and participles.

Unfair, unwise, unforgettable, unassuming, unexpected.

REVERSATIVE OR PRIVATIVE PREFIXES

DE- “reversing the action”, combines fairly with verbs and deverbal nouns.

Decentralize, defrost, desegregate. Also with the meaning of “depriving of”, with verb

and deverbal nouns: decapitate, deforestation.

DIS- “reversing the action”, combines fairly freely with verbs: disconnect,

disinfect, disown. Also with the meaning “lacking”, as in disinterested, discoloured.

UN- “reversing the action”, combines fairly freely with verbs: undo, untie, unzip.

STATUS

ARCH- “chief” archbishop

CO- “joint” co-founder

PRO- “deputy” proconsul

VICE- “deputy” vice-president

PEJORATIVE PREFIXES

MAL- “badly, bad”, combines with verbs, participles, adjectives, and abstract

nouns: maltreat, malformed, malodorous, malfunction.

MIS- “wrongly”, “astray”, combines with verbs, participles and abstract nouns:

miscalculate, misunderstand, misinform, misleading.

PSEUDO- “false”, “imitation”, combines freely with nouns and adjectives:

pseudo-Christianity, pseudo-classicism.

CRYPTO- “concealed”. Crypto-fascist, crypto-Catholic.

PREFIXES OF DEGREE OR SIZE

ARCH- “supreme”, “most”, combines freely with nouns, chiefly with human

reference: archduke, archbishop, and usually with pejorative effect: arch-enemy, archfascist. Archangel is an exception of non-hyphenation.

CO- “jointly”, “on equal footing”, combines freely with nouns and adverbs: coopt, cooperate, coexist. In some nouns, the prefix is stressed: co-driver.

HYPER- “extreme”, combines freely with adjectives: hypersensitive,

hypercritical.

MEGA- “very large” megastar.

MACRO- “large” macrocosm

MICRO- “small” microsurgery

MIDI- “medium” midibus

MINI- “little”, combines freely with nouns: mini-market, mini-skirt.

10

UNIT 10: WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND COMPOUNDS

OUT- “surpassing”, combines freely with nouns and intransitive verbs to form

transitive verbs: outnumber, outclass, outdistance.

OVER- “excessive (hence pejorative), combines freely with verbs and adjectives:

overeat, overestimate.

SUB- “below”. It combines with adjectives. Subconscious, subnormal.

ULTRA- “Extreme”, “beyond”, combines freely with adjectives (hyperboles like

ultra-modern, ultra-conservative); technical items like ultrasonic and with nouns in

technical usage, sometimes with the prefix stressed: ultramicroscopic, ultrasound.

UNDER- “too little”, combines freely with verbs and –ed participles

(undercharge, underestimate, underplay) and corresponding nouns (underprovision; with

the meaning “subordinate”, it combines less commonly with nouns (undermanager)

PREFIXES OF ORIENTATION AND ATTITUDE

ANTI- “against” combines freely with denominal adjectives (anti-social, anticlerical) and nouns, mainly to form premodifying adjectives (anti-war campaign).

CONTRA- “opposite”, “contrasting”, combines with nouns, verb, and denominal

adjectives: contradistinction, contraindicate.

COUNTER- “against”, “in opposition to”, combines with verbs, abstract nouns,

and denominal adjectives: counter-espionage, counter-clockwise.

PRO- “for”, “on the side of”, combines freely with denominal adjective and

nouns, mainly to form premodifying adjectives: pro-communist, pro-American.

LOCATIVE PREFIXES

ANTE- “before”. Antechamber, ante-room.

CIRCUM- “around”. Circumnavigate.

EXTRA- “outside”, “beyond”. Extramarital, extracurricular.

FORE- “front part of”, “front”, combines fairly freely with nouns such as

forearms, foreshore, foreground.

IN- IM- IL- IR- “in” ingathering, indoors.

INTER- “between”, “among”, combines freely with denominal adjectives, verbs

and nouns: international, interlinear, intertwine. With nouns, the product is chiefly used

in premodification: inter-war, inter-school.

INTRA- “inside”. Intramural, intravenous.

MID- “middle”. Midfield.

OUT- “Outside”. outdoor, out-patient.

OVER- “from above”, “outer” overthrow, overshadow.

RETRO- “backwards”. Retroflex.

SUB- “under”, combines fairly freely with adjectives, verbs and nouns:

subnormal, sublet, subdivide, subway.

SUPER- means “above: superstructure, superscript.

SUPRA- “above”. Supranational.

SUR- “above”. Surcharge.

TELE- “at a distance”. Television.

TRANS- “to the other side”: transatlantic.

ULTRA- “beyond”, “extremely”. Ultraviolet, ultra-modest.

11

UNIT 10: WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND COMPOUNDS

UNDER- “below”, “too little”, “subordinate”. Undercharge, undercook, undersecretary.

PREFIXES OF TIME AND ORDER

ANTE- “before” antenatal

EX- means “former” and is added to nouns: ex-wife.

FORE- “before” foresee

MID- “middle” midwinter

NEO- “new”, “recent form of” neocolonialism

POST- “after” post-modernism

PRE- means “before”, “in advance”, and is added to nouns, adjectives and

adverbs: pre-school, pre-marital.

RE- “again” reprint, renew.

NUMBER PREFIXES

MONO- combines with nouns and adjectives: monoparental.

SEMI- combines with nouns and adjectives: semicircle, semi-detached.

UNI- “one” undirectional

POLY- “many” polysyllabic

MULTI- “many” multi-faith

SEMI- “half”, “partly” semicircle, semi-conscious

DEMI- “half”, “partly” demisemiquaver, demigod

HEMI- “half” hemisphere

BI- “two” bilabial

DI- “two” dioxide

DUO-, DU- “two” duologue

TRI- “three” tridimensional

CONVERSION PREFIXES

Their chief function is to effect a conversion of the base form from one word class

to another. They are unstressed.

ACombines freely with verbs to yield predicative adjectives: asleep, astride,

awash, atremble, aglow.

BE- functions along with –ed to turn noun bases into adjectives with somewhat

more intensified force than is suggested by –ed alone: bewigged, bespectacled, befogged,

bedewed.

EN-, EM- before /p/, /b/, combines chiefly with nouns to yield verbs: enmesh,

empower, endanger, enflame.

MISCELLANEOUS

AUTO- “self” autobiography

BIO- abbreviation of biology and biological : biodegradable

ECO- abbreviation of ecology and ecological: eco-friendly

EURO- abbreviation of Europe and European: Eurocurrencies

PARA- “ancillary”: paranormal

SELF- self-control

12

UNIT 10: WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND COMPOUNDS

Several affixes seemed to find new life in the 1980s: mega- (-trendy, -sulk, -worry,

-terror, -brand, -city).

Suffixes

As with prefixes, we shall concentrate on those suffixes that are in commonest

productive use. Our treatment of suffixes is on a generally grammatical basis. This is

because, while prefixes primarily effect a semantic modification of the base, suffixes have

by contrast only a small semantic role, their primary function being to change the

grammatical function of the base. Thus, it is convenient to group them according to the

word class that results when they are added to the base. But, in addition, since particular

suffixes are frequently associated with attachment to bases of particular word classes, it

is also convenient to speak of them as DENOMINAL SUFFIXES, DE-ADJECTIVAL

SUFFIXES, etc.

Unlike prefixation, suffixation with originally foreign items is often accompanied

by stress shifts and sound changes determined by the foreign language concerned. Thus,

even where the spelling of the base remains constant, the stress differences in sets like the

following involve sharply different vowel sounds. For instance, the graph element in the

following is pronounced /a:/, /ə/ and /æ/ respectively.

‘photograph – pho’tography – photo’graphic

Spelling may also be affected:

Invade – invasion ; persuade – persuasion

Permit – permission ; admit – admission

‘drama – dra’matic

Able – ability

In’fer – ‘inference – infe’rential

13

UNIT 10: WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND COMPOUNDS

NOUN SUFFIXES

Denominal nouns: Abstracts

Noun bases become largely noncount abstract, or aggregate nouns of status or

activity, by means of the following suffixes:

-AGE “measure of”, “collection of”: baggage, frontage.

-DOM officialdom (with pejorative overtones, except in stardom and kingdom).

-ERY “the condition or behaviour associated with”: drudgery, slavery, devilry, nitwittery,

take-over-biddery. Also “location of”: nursery, refinery, bakery. Noncount concrete

aggregate nouns are rather freely formed, as in machinery, rocketry.

-FUL “the amount contained in”: spoonful

-HOOD boyhood, manhood, brotherhood. The base sometimes is an adjective, as in

falsehood.

-ING tubing, panelling, carpeting. Also “the activity connected with”: cricketing,

farming.

-ISM “practice of”: Calvinism, idealism.

-OCRACY “government by”: democracy, aristocracy.

-SHIP friendship, membership.

Denominal nouns: Concrete

-EER “skilled in”, “engaged in”: pamphletter, profiteer, engineer.

-ER “having a dominant characteristic”, “denizen of”,: teenager, north-wester, threewheeler, villager, Londoner.

-ESS

waitress, actress, lioness.

-ETTE “compact”: kitchenette, dinerette. Also “imitation”: flannelette, leatherette.

Feminine marker in suffragette, usherette.

- LET “small”, “unimportant”,: booklet, piglet.

-LING “minor”, “offspring of”,: princeling, duckling, hireling.

-STER “involved in”, trickster, gangster, gamester.

Noun/adjective suffixes

-ESE “member of”: Chinese, Japanese.

-(I)AN “adherent to”: Darwinian, republican. Also “relating to”: Shakespearian,

Chomskyan. “Citizen of”: Indonesian, Chicagoan, Glaswegian. “The language of”:

Russian, Indonesian.

14

UNIT 10: WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND COMPOUNDS

- IST “skilled in”, “practising”: violinist, socialist.

-ITE “adherent to”, “member of”: Benthamite, shamanite, socialite. Also “denizen of”:

Brooklynite, Hampsteadite.

ADJECTIVE SUFFIXES

Denominal suffixes

-ED “having”: wooded, pointed, simple-minded, blonde-haired.

-FUL “providing”: useful, delightful, pitiful.

-ISH “somewhat like”: childish, monkeyish; with adjectives: brownish, greyish; with

people’s ages, “approximately”: sixtyish; with names of races, peoples and languages:

Swedish, Cornish.

-LESS “without”: careless, restless.

-LIKE “like”: childlike, statesmanlike,.

-LY “having the qualities of”: womanly, soldierly, motherly; also with nouns that are units

of time, with the meaning of “every”: hourly, weekly, etc.

-Y “somewhat like”, “characterized by”: sandy, meaty, creamy.

-AL (-IAL, -ICAL) accidental, dialectal, editorial, psychological, cultural.

-ESQUE burlesque, romanesque, Kafkaesque, Daliesque.

-IC atomic, heroic, problematic, phonematic, Celtic, Arabic.

-OUS (-IOUS) especially when replacing –ion, ity: desirous, virtuous, grievous,

ambitious, courteous, erroneous.

Deverbal suffixes

Two common suffixes are used to form adjectives from verbs and they are in polar

contrast in respect of verbal voice: -ive is fundamentally related to the active, “of the kind

that can V”; -able is fundamentally related to the passive: “of the kind that can be V-ed”.

Thus:

The idea attracts me the idea is attractive

The text cannot be translated the text is unstranslatable

-ABLE debatable, washable. Sometimes –ible, -uble: inevitable, soluble, visible.

-IVE attractive, possessive, productive, explosive, expansive, decorative, talkative.

ADVERB SUFFIXES

-LY calmly, economically, slowly.

15

UNIT 10: WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND COMPOUNDS

-WARD(S) onwards, northwards, theatre-wards, Chicago-wards.

-WISE clockwise, crabwise, crosswise, lengthwise.

VERB SUFFIXES

-ATE orchestrate, hyphenate.

-EN deafen, sadden, tauten, quicken.

-IFY, -FY simplify, amplify, certify, identify, electrify.

-IZE, -ISE symbolize, publicize, dieselize.

CLIPPING

A part of a word which serves for the whole (ad, phone, bra). There are two chief

types:

- The first part of the word is kept (the most common): demo, exam, pub.

- The last part of the word is kept: bus, plane.

Sometimes, a middle part is kept, as in fridge and flu.

There are also several words which retain material from more than one part of the

word, such as maths (UK), gents and specs. Turps is a curiosity, in the way it adds an

<s>.

Several clipped forms also show adaptation, such as fries (from French fried

potatoes), Betty (from Elizabeth) and Bill (from William).

16

UNIT 10: WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND COMPOUNDS

CONVERSION

Lexemes can be made to change their word class without the addition of an affix

– a process known as CONVERSION. The items chiefly produced in this way are nouns,

adjectives, and verbs – especially the verbs which come from nouns (e.g. a doubt). Not

all the senses of a lexeme are usually carried through into the derived form, however. The

noun paper has several meanings, such as “newspaper” “wallpaper”, and “academic

article”. The verb to paper relates only to the second of these. Lecturers and editors may

paper their rooms, but not their audiences or readers.

verb to noun

A swim/hit/cheat/bore/show-off/drive-in

adjective to noun

A bitter/natural/final/monthly/regular/wet

noun to verb

To bottle/catalogue/oil/brake/referee/bicycle

adjective to verb

To dirty/empty/dry/calm down/sober up

noun to adjective

It’s cotton/brick/reproduction

grammatical word to noun

Too many ifs and buts

But me with no buts (William Shakespeare)

That’s a must

The how and the why

Affix to noun

Ologies and isms

phrase to noun

A has-been/free-for-all/also-ran/down-and-out

grammatical word to verb

To down tools/ to up and do it

17

UNIT 10: WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND COMPOUNDS

BACK-FORMATION

It is common in English to form a new lexeme by adding a prefix or a suffix to an

old one. From happy we get unhappy; from inspect we get inspector. Every so often,

however, the process works the other way round, and a shorter word is derived from a

longer one by deleting an imagined affix. Editor, for example, looks as if it comes from

edit, whereas in fact the noun was in the language first. Similarly, television gave rise to

to televise, double-glazing preceded double-glaze, and baby-sitter preceded baby-sit.

Such forms are known as BACK-FORMATIONS.

Each year sees a new crop of back-formations. Some are coined because they meet

a real need as when a group of speech therapists in Reading in the 1970s felt they needed

a new verb to describe what they did – to therap. Some are playful formations, as when

a tidy person is described as couth, kempt, or shevelled. Back-formations often attract

criticism when they first appear, as happened in the late 1980s to explete (to use an

expletive) and accreditate (from accreditation).

REDUPLICATIVES

Some compounds have two or more constituents which are either identical or only

slightly different: goody-goody (“a self-consciously virtuous person”). The difference

between the two constituents may be in the initial consonants: walkie-talkie, or in the

medial vowels: criss-cross. Most of the reduplicatives are highly informal or familiar,

and many belong to the sphere of child-parent talk: din-din (“dinner”). The most common

uses of reduplicatives (also called JINGLES) are:

to imitate sounds: rat-a-rat (knocking on door), tick-tock, ha-ha, bow-wow.

to suggest alternating movements: see-saw, flip-flop, ping-pong.

to disparage by suggesting instability, nonsense, insincerity, vacillation, etc: higgledypiggledy, hocus-pocus, wishy-washy, dilly-dally, shilly-shally.

to intensify: teeny-weeny, tip-top.

BLENDING

A lexical blend, as its name suggests, takes two lexemes which overlap in form,

and welds them together to make one. Enough of each lexeme is usually retained so that

the elements are recognizable. Here are some long-standing examples, and a few novelties

from recent publication,

Breakfast + lunch = Brunch.

Motor + hotel = motel

18

UNIT 10: WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND COMPOUNDS

Helicopter + airport = heliport

Smoke + fog = smog

Advertisement + editorial = advertorial

Channel + tunnel= chunnel

Oxford + Cambridge =Oxbridge

Yale + Harvard = Yarvard

Slang + language=slanguage

Guess+ estimate=guesstimate

Square + aerial=squaerial

Toys+cartoons= toytoons

Breath + analyser=breathalyser

Affluence + influenza = affluenza

Information + commercials= infomercials

Dock + condominium = dockominium

In most cases, the second element is the one which controls the meaning

of the whole.

Blending increased in popularity in the latter half of the 20th century, being

increasingly used in commercial and advertising contexts. Products were sportsational,

swimsational and sexsational. TV provided dramacons, docufantasies, and

rockumentaries. The forms are felt to be eye-catching and exciting; but how many of

them will persist remains an open question.

Scientific terms frequently make use of blending, as in bionic, as do brand names

(teledent) and fashionable neologisms.

ACRONYMS

They are pronounced as single words (laser, NATO, jomo). They never have

periods separating the letters – a contrast with initialisms, where punctuation is always

present, especially in older styles of English).

19

UNIT 10: WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND COMPOUNDS

EPONYMY

A new word is created from somebody’s name.

Leotard, from the acrobat Jules Leotard.

Most do not last and are labelled as NONCES (temporary words that never

properly enter the language).

OTHER TYPES OF ABBREVIATIONS:

INITIALISMS: items which are spoken as individual letters, such as DJ, BBC,

USA. They are also called ALPHABETISMS. Not all of them use the first letter of the

constituent words: PhD uses the first two letters, and GHO and TV take a letter from the

middle of the word.

AWKWARD CASES: some forms can be used either as initialisms or

acronyms (U.F.O., UFO or you-foe).

Some mix these types in the one word (CDRom).

Some can form part of a larger word using affixes (ex-JP, pro-BBC, JCBMs).

Some are only used in writing, but pronounced in full: Mr, St.

FACETIOUS FORMS:

TGIF Thanks God it’s Friday (properly “Companion of St Michael and St

George)

CMG Call me God (“Companion of St Michael and St George”)

KCMG kindly call me God (“Knight Commander of St Michael and St George”)

GCMG God calls me God (“Grand Cross of St Michael and St George”)

AAAAAA Association for the Alleviation of Asinine Abbreviations and Absurd

Acronyms.

20

UNIT 10: WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND COMPOUNDS

21

UNIT 10: WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND COMPOUNDS

BAGONIZING

However, native speakers seem to have a mania for trying to fill lexical gaps. If a

word does not exist to express a concept, there is no shortage of people very ready to

invent one. Following a ten-minute programme about neologisms on BBC Radio 4 in

1990, over 1,000 proposals were sent in for new English lexemes. Here are some

examples:

Aginda: a pre-conference drink

Circumtreeaviation: the tendency of a dog on a leash to want to walk past poles

and trees on the opposite side to its owner

Blinksync: the guarantee that, in any group photo, there will always be at least one

person whose eyes are closed

Fagony: a smoker’s cough

Litterate: said of people who care about litter

Polygrouch: sb who complains about everything

22

UNIT 10: WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND COMPOUNDS

Leximania: a compulsive desire to invent to words

Bagonize: to wait anxiously for your suitcase to appear on the baggage carousel.

BROADENING

Broadening is the process by which the meaning of a word changes to become

more generalised over time. Broadening is a type of semantic change. It is important that

we first understand what semantics and semantic change are.

Semantics refers to the study of the meaning of words or phrases. There

are two types

of

semantics: logical and lexical. Logical semantics

has to

do

with reference (the symbolic relationship between language and real-world

objects) and implication (the

relationship

between

two

sentences).

Lexical semantics has to do with word meaning.

Semantic change refers to how the meanings of words change over time.

Broadening is a key example of semantic change and is a common process that

tends to occur slowly over many years. A synonym of broadening is a semantic

generalisation.

Semantic broadening is caused by extra-linguistic factors. These are factors that occur

outside the language itself. This type of semantic change occurs naturally and gradually

over time.

Broadening typically occurs when a word is used more frequently. This will lead to

its meaning becoming more encompassing of related definitions. This can be caused by

factors such as socio-cultural and psychological reasons. Let's take a look at some

examples.

1. Socio-cultural factors

Sociocultural factors can cause broadening. This happens when there is a major shift

in a country's politics or social landscape. Revolutions, wars, and civil rights movements

can all lead to broadening. A good example of this is how some words change their

meaning following political coups.

Guy

The word 'guy' gained popularity in England following the failed Gunpowder Plot

led by Guido 'Guy' Fawkes. Because of Fawkes' role in the plot, the word 'guy' came to

mean a grotesque person. This developed over time until the word meant a man or boy.

23

UNIT 10: WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND COMPOUNDS

2.

Psychological Factors

Broadening can also happen when an item gains popularity. This is especially

common in the twentieth century. When a brand becomes the leader in its field,

sometimes its meaning will broaden to include the entire field itself. This will lead to the

word meaning becoming broader in the minds of its consumers.

Tissues

Kleenex

The tissue brand, 'Kleenex' is often used interchangeably with the word

'tissue'. This is because, as the product became more popular, people began to link the

two in their minds, leading to the broadening of the meaning of the word.

Examples of broadening

1. Business

A business

The word 'business' was originally only used to mean someone was

busy. However, over the years, the meaning of this word has changed. Now, the word's

meaning has been broadened to refer to any type of work or job.

2.

Cool

The modern use of the term 'cool' was originally used in jazz to refer to a specific

style ('cool jazz')! As jazz grew in popularity, the word started to be applied more widely.

3.

Demagogue

'Demagogue' derives from the Greek word 'demos', meaning 'people'. Historically

it was used to describe a popular leader. However, this meaning broadened through the

years to indicate a political leader who panders to the prejudices of the masses.

Broadening - key takeaways

Semantics refers to the study of meaning.

Semantic change refers to how the meaning of a word can change over time.

24

UNIT 10: WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND COMPOUNDS

Broadening is when the meaning of a word becomes broader and more generalised

over time.

Broadening is typically caused by extralinguistic factors.

NARROWING

Narrowing is a process that takes place in semantics. It is important that we first

understand what semantics is and what semantic change is.

Semantics refers to the study of the meaning of words or phrases. There

are two types of semantics: logical and lexical. Logical semantics has to do

with reference (the symbolic relationship between language and real-world

objects) and implication (the

relationship

between

two

sentences).

Lexical semantics is about the analysis of word meaning.

Semantic change refers to how the meaning of words changes over time.

Narrowing is a type of semantic change in which the meaning of a word becomes

less generalised over time. Narrowing may also be called 'semantic

specialisation' and is a common process that can occur slowly over many years.

The opposite of semantic narrowing is called semantic broadening. This is when

a word's meaning becomes more generalised over time.

What causes narrowing?

Semantic narrowing is typically caused by extra-linguistic factors. These are

defined as factors that occur outside the system of the language spoken. This type of

semantic change occurs naturally and gradually over time.

Narrowing is typically caused when a definition of a word is used more commonly

than other definitions so the word's meaning changes to be more specific. This can be

caused by factors such as socio-cultural and psychological reasons.

Let's take a look at some examples of this.

Sociocultural causes

Sociocultural factors can also cause narrowing. This happens when there is

a major shift in a country's politics or social landscape. Factors such as revolutions,

wars and civil rights movements can lead to narrowing. One major example of this is

how the meaning of some words changed following the Industrial Revolution.

25

UNIT 10: WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND COMPOUNDS

Engine

The word engine (known as 'egin' in Old French and 'egyn' in Middle English)

was traditionally used to describe machines used in war. Before industrialisation the word

was used to describe devices used in war, such as catapults. Following the Industrial

Revolution, the word came to mean a mechanical device used to achieve a purpose. This

shows that the word's meaning became narrower over time.

Psychological Causes

Narrowing can also happen when a language undergoes widespread

change. Major changes like this can affect how people view a word and its meaning. This

is especially common when the meaning of word becomes taboo or is used as a

euphemism, like the way that 'passed away' can be used to describe someone dying.

Hound

The word 'hound', comes from the German word, 'hund', meaning 'dog'. It was then

traditionally used to refer to any type of dog in English also. However, over the centuries,

as the English language developed, the meaning narrowed, until it was only used for dogs

and related to the action of hunting (using breeds like beagles and bloodhounds).

Examples of narrowing

Now that we have established what semantic narrowing is and how it occurs, let's

look at some examples.

Meat

The word 'meat' has undergone semantic narrowing over the years. The word

originally just meant 'food'. In time, this meaning grew to become more specific, until the

word 'meat' was only used for one type of food (the flesh of an animal).

Deer

Originally, 'deer' came from the Old English word 'dēor'. Records from before 900

AD show that this word meant 'beast', and was used to refer to any four-legged

animal. However, by 1400 AD, the meaning of the word had significantly narrowed to

only refer to one type of creature.

Girl

A similar process occurred for the word 'girl'. The word was used in Middle

English to refer to any young child, regardless of gender. Over time this changed, and

now the word is only used to refer to young and adolescent women.

Narrowing - key takeaways

Semantics is a term that refers to the study of the meaning of words.

26

UNIT 10: WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND COMPOUNDS

Semantic change refers to how the meaning of a word can change over time.

Narrowing is a specific process of semantic change where a word's meaning becomes

more specific over time.

This is a common process that often takes place over many years.

Narrowing can be caused by socio-cultural and psychological factors.

3. False Friends

When a student is learning a second language a phenomenon which often appears is

LEXICAL TRANSFER, by which the learner attributes to a word of the foreign language

all the characteristics that a very similar word of his own language has (semantically and

morphologically). For example, Spanish learners of English would associate frequent to

“frecuente”, or dictionary to “diccionario”. These words are known as COGNATES or

POSITIVE TRANSFERS.

But lexical transfers can also be negative and produce FALSE FRIENDS. They are

words which have a similar or identical form in spelling in both languages, often the same

syntactic function, but whose meanings are completely different. Naturally, these FALSE

FRIENDS are responsible for important misunderstanding. Some typical examples are:

WORD

USUAL WRONG TRANSLATION

RIGHT TRANSLATION

Carpet

carpeta

alfombra

Large

largo

grande

Success

suceso

éxito

Actual

actual

real

Library

librería

biblioteca

The most common forms of semantic transfer are:

Metaphor

Metaphor is a type of figurative language that refers to one thing as another

thing to make us see the similarities between them. Metaphor helps us make effective

comparisons. If any of this sounds confusing, don’t worry – it will be much easier to

understand once we start looking at some examples.

Let’s look at a few examples of metaphor; you may already be familiar with one

or two of them.

Life is a rollercoaster.

Think about the experience of being on a rollercoaster – there are ups and downs,

twists and turns, and it can be both terrifying and exhilarating. You could describe life in

exactly the same way.

“I’m a hot air balloon that can go to space”.

27

UNIT 10: WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND COMPOUNDS

This line is from Pharrell’s song, “Happy”, and it’s a perfect example of metaphor.

The song, as the title suggests, is all about being happy and feeling good. By describing

himself as “a hot air balloon”, we can picture Pharrell floating off the ground into space,

giving us an idea of how light and carefree his mood is.

“Conscience is a man’s compass”.

Vincent Van Gogh, the famous artist, wrote this in a letter to his brother. Think of

what a compass does – it shows you the way and prevents you from getting lost. Now

think of conscience – a person’s moral sense of right and wrong. Here, Van Gogh makes

us imagine conscience as the compass within us, guiding us through life.

Of course, life isn’t really a rollercoaster, Pharrell isn’t really a hot air balloon and

there isn’t an actual compass inside any of us! Metaphors are symbolic, which is why

they are classed as figurative language, or figures of speech – in other words, they are

not to be taken literally, but they create images in our minds to express thoughts, feelings

and ideas.

Going back to our original definition, a metaphor refers to one thing as another

thing to help us see the similarities between them. Let’s break down the line from

“Happy” to help us understand this – Pharrell expresses his emotion by saying, “I’m a hot

air balloon”; he is referring to one thing (himself) as another thing (a hot air balloon).

This makes us think of the similarities between them: hot air balloons are light and have

a fire burning inside that help them to travel upwards; similarly, Pharrell’s mood is light,

energetic, and moving upwards – you could say that there’s a fire inside him and so he

feels as if he can float, just like the balloon.

Metaphors contain two parts; the tenor and the vehicle. Let’s take the same three

examples and split them into tenor and vehicle:

Tenor

Vehicle

Life

A rollercoaster

Pharrell

A hot air balloon

Conscience A compass

The tenor is the thing that you want to describe. It could be a person, an object or

a concept. In “life is a rollercoaster”, life is the tenor.

The vehicle is the main imagery of the metaphor; it is what the tenor is being

compared to. In “life is a rollercoaster”, a rollercoaster is the vehicle.

Dead metaphors

Some everyday metaphors (or idioms) are so common or overused that they have lost

their original imagery. These are called dead metaphors. Examples of dead metaphors

include: "a body of work", “the foot of the bed” and "time is running out". In this last

example, the metaphor originally compared time to the sand "running" down in an

hourglass. Now, we use this term without thinking of the original imagery or comparison

at all; it has become a dead metaphor.

28

UNIT 10: WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND COMPOUNDS

You may occasionally hear somebody mix two or more everyday metaphors

together; the result, a mixed metaphor, is usually inconsistent or confusing.

For example, let’s say somebody tells you, “Those in glass houses should get

out the kitchen”. Here, they have mixed two idioms: “those in glass houses shouldn’t

throw stones” and “if you can’t stand the heat, get out the kitchen”. The message is

unclear, as these metaphors mean different things – they don’t belong together!

Sometimes people combine two phrases that mean the same thing to create a

mixed metaphor. For example, they might express how happy they are by saying, “I’m

walking on the moon”; they have mixed the idioms, “I’m walking on sunshine” and “I’m

over the moon”.

Usually, when people use mixed metaphor, it’s by accident. But you can use it

deliberately if you want to create a silly, comedic effect.

Metonymy

Metonymy is a type of figurative language, or a figure of speech, that refers to

a thing by the name of something associated with it. The word that replaces the original

thing is called a metonym.

Metonymy for people and objects

One of the most famous examples is “the crown” as a metonym for the monarch

(a king or queen – for the sake of this example we’ll say there’s a queen in charge). If

somebody was to say, “I swore allegiance to the Crown”, this doesn’t literally mean that

they pledged their loyalty to a piece of fancy headwear – really they are saying, “I swore

allegiance to the Queen”. A crown is something closely associated with a queen, which

is why you can replace the word “queen” with “crown” and we still understand what it

means.

Have you ever heard anybody refer to businesspeople as “suits”? An example of

this could be, “I’m going for a meeting with the suits from head office”. In this sentence,

“suits” is a metonym for businesspeople.

Ever seen an action movie where somebody mentions “a hired gun”? They’re

most likely referring to a person associated with a gun: an assassin.

Some metonyms are so common that we barely even notice them. For example, if

I asked you, “What’s your favourite dish?” I wouldn’t expect you to reply, “bone china”

or “porcelain”! Most people would understand the question as, “What’s your

favourite meal?” – therefore, “dish” is a metonym for meal.

Another subtle example of metonymy is if I asked, “Have you heard the new Billie

Eilish?” What I really mean is, “Have you heard the new Billie Eilish song?” It’s common

to refer to an artist’s work by their name; another example of this would be, “I’ve got

a Picasso hanging up in my living room”.

29

UNIT 10: WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND COMPOUNDS

There are a lot of slang terms for “money”, but one of the most common (and one

that works as a metonym) is “bread” (or sometimes “dough”); for example, “I need a job

so I can start making some bread”, or, “I need a job so I can start making some dough”.

Bread (which is made from dough) is something closely associated with money, as we all

know that having money means that you can eat!

Metonyms aren’t limited to just nouns; they can also be verbs or any other type of

word, as long as there is a close association. For example, if I said, “My ride is parked

outside”, “ride” would be a metonym for car. This works even though “ride” is a verb

because there is a close association – you “ride” in a car.

Metonyms for abstract concepts

You can also use metonymy to refer to abstract concepts, ideas and emotions. For

example, “from the cradle to the grave” is a common expression meaning

“from birth until death”; in this phrase, “the cradle” is a metonym for birth, and “the

grave” is a metonym for death. Similarly, there are parts of the world known as

“cradles of civilization”; this phrase refers to the fact that early cultures developed in

these places; they are birthplaces of civilization.

“Heart” can be used as a metonym for several things. The most obvious meaning

is love, as in, “I gave you my heart”; we understand this as meaning, “I gave you

my love”. Also, if you “put your heart” into something, it can mean that you have put

passion, energy, or effort into it. “Heart” works as a metonym in both contexts.

Examples of metonymy: a recap

30

UNIT 10: WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND COMPOUNDS

Similes

The clue is in the name - simil e is all about simil arity. Simile uses connecting

words such as “like”, “as” or “than”; for example: “running like the wind”, “as hot as a

sauna” or “more cunning than a fox”. Simile is one of the most common techniques in

creative writing, but it's also very common to hear it in everyday language.

Examples:

As cold as ice.

You could use this phrase to describe something that is physically very cold, or

you could use it to describe a nasty or unfriendly person. Either way, by comparing that

thing (the object or someone's personality) to ice, you are making a point about just how

cold it is.

Like watching paint dry.

Can you think of anything more boring than watching paint dry? By drawing a

comparison to this extremely tedious activity, we get the idea that the thing you are

describing is not exactly thrilling!

As clear as mud.

You would normally use this phrase to describe something that is confusing or

hard to understand. This comparison comes from the fact that you cannot see through

mud - it's the opposite of clear! If somebody were to say, "The instructions are as clear

as mud", we understand this to mean, "The instructions are not clear at all". This is an

example of simile, comparing two things to draw attention to their differences.

It's worth noting that these three phrases are also examples of idioms An idiom

is a figure of speech that has become common in everyday conversation.

Personification

Just look at the word itself - person ification. Think of it as meaning “turning

something into a person”. Like metaphor and simile, personification is a type

of figurative language, or a figure of speech, meaning that it expresses an idea or feeling

in a way that is non-literal.

The best way to understand personification is by looking at examples; in this

section we'll dissect some lines by famous writers, but first, here are a few phrases that

you might hear in everyday conversation.

Examples:

A raging storm.

In this example, the speaker describes a storm as if it has an emotion - we know

that a storm doesn't literally feel rage, but the phrase helps us to picture it as an aggressive

force.

The groaning floorboards.

Not only does the word "groaning" help us to imagine the creaking sound of the

wood, but it suggests a particular attitude - we get the idea that the floorboards are jaded

and miserable - well, wouldn't you be if people kept walking all over you?

31

UNIT 10: WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND COMPOUNDS

Idioms

They are:

A figure of speech, meaning that it is not to be taken literally.

A well-established phrase or expression.

A phrase or expression that is specific to a particular language or dialect - if

you were to directly translate an idiom into another language, it would make no

sense.

Are you ready to look at some examples of idioms? Well, let's "get the ball rolling" ...

There are many, many idioms in the English language (The Oxford Dictionary of

Idioms lists over 10,000!). We've picked five common idioms that you may already be

familiar with from everyday language (with some fun facts about their origins). Idioms

from everyday language:

Start from scratch.

To “start from scratch” means to start from the very beginning without being able

to build on something that already exists.

If you lost all of your work and didn't have a backup, you could say, "Now I have

to start again from scratch!" Or, if you were to bake your own bread from raw ingredients,

then you could state, "I made this bread from scratch".

As you can see, these are figurative uses of the term, as neither of them involve

any actual scratching.

This idiom most likely originates from cricket; lines have to be scratched into the

ground to mark the pitch before a game begins, hence “starting from scratch”.

Let the cat out of the bag.

To "let the cat out of the bag" means to accidentally give away a secret. This could

mean revealing too much information in a conversation and then getting caught out.

For example, you're talking to your teacher and you accidentally mention the party

you went to when you should have been revising: "I can't believe it, now I've let the cat

out of the bag!" Or let's say you bought a surprise gift for your friend and they find the

receipt: "Well, the cat's out of the bag now!"

Once again, these are figurative uses of the term as there is no actual cat

involved.

This idiom originates from the 1700s; Merchants would sell piglets in bags, but

would often trick customers by giving them a bag with a cat inside. If the cat got out of

the bag, then the trick would be ruined; the cat would be literally out of the bag.

32

UNIT 10: WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND COMPOUNDS

Synecdoque

Synecdoche is a type of figurative language, or a figure of speech , that refers to

a thing by either the name of something that is part of it , or by the name of something

that it is part of . In other words, it is a part that refers to the whole , or a whole that

refers to the part .

Examples:

A part that refers to the whole

If somebody were to pull up in a new car and say, "Check out my new wheels", it

is unlikely that you would start inspecting the tyres - you would probably understand the

phrase as, "Check out my new car ". They have just mentioned a part (“wheels”) to refer

to the whole (the car).

There are quite a few common phrases that use synecdoche in this way - for

example, "I've got mouths to feed". Nobody has disembodied mouths floating around on

their own that need feeding (we hope!), And so we understand this phrase as, “I've

got people to feed”; mouths are a part of people. By drawing attention to this particular

body part, you are emphasizing that the people need feeding.

Ever heard the phrase “all hands on deck”? Here the word “hands” refers to people

- as hands are also a part of people. In this case, you are drawing attention to the hands

because you are most likely calling for these people to help with manual work.

If you were to see a man with a moustache walking down the street and yell, “Hey,

moustache!” he would know that you were talking to him , not the moustache

(disclaimer: please don't try this with any strangers!). The moustache is a part of him

because it's attached to his face.

“Bar” is another common synecdoche, as in, “We had a few drinks in a bar”. Once

again, the part (the “bar”, where staff serve drinks) refers to the whole (the entire pub or

club).

We often refer to objects by the name of something that they are physically made

of; Examples of this include a "glass" that you drink from, or "plastic" in reference to a

credit or debit card. These terms are classed as synecdoche, as once again the part (an

element that it is made of) refers to the whole (the complete object).

In all of these examples, we are referring to a thing (such an object or a person)

by the name of something that is a part of it. You can think of this type of synecdoche

as zooming in on a particular detail of a thing.

The whole that refers to the part

"Watch out, the police are coming!" If you heard somebody shout this phrase, you

wouldn't assume that the entire police force are coming round the corner - it would be

several officers who work for the police. And so in this phrase, there is a whole (“the

police”) that refers to a part (some police officers).

33

UNIT 10: WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND COMPOUNDS

Let's say a parent speaks to their child and tells them, “I've had a word with your

school”; we understand this as meaning, “I've had a word with the teachers at your

school ”. The school is a whole that contains the teachers.

Are you starting to get the picture? You can think of this type of synecdoche

as zooming out to reveal the whole that a thing is part of.

An extremely common use of this type of synecdoche is using the name of a

place (such as a country or city) to represent a group of people or an industry that is

based there . One example of this is the term “Hollywood”, meaning the mainstream

movie industry. As many major studios are based in Hollywood, California, you could

say, "I hope to make it in Hollywood" and we would assume that you are trying to become

a movie star.

In any international sports match, people refer to each team by the name of the

country they represent, for example: “Germany is playing Italy”. What this means is, "The

German football team is playing the Italian football team".

Other examples include:

“Broadway” or “The West End” to mean mainstream theatre (as in, “She's a

Broadway star”, or “It was a West End flop”).

“Downing Street” to mean the UK Prime Minister and staff (as in, “Downing

Street announces latest budget”).

“The White House” to mean the US president and staff (as in, “The White House

releases details of climate initiative”).

34

UNIT 10: WORD-FORMATION: PREFIXES, SUFFIXES AND COMPOUNDS

Oxymoron

An oxymoron is a figure of speech that puts two words next to each other with

very different meanings that end up making sense in a strange way. The first word is

usually used to describe the second word in a way that contrasts with it.

Old news is an everyday example of an oxymoron, as news is meant to be

current.

It might be quite hard to wrap your head around this definition - how on earth can

opposites make sense together? Let's take a look at some examples to explain.

Oxymorons are probably more common than you think. These examples should

help you understand how oxymorons are used, and how two opposites together can make

sense!

There are hundreds of oxymorons, so let's take a look at some of the most common

ones.

Deafening silence. The two words which make up this oxymoron mean

completely different things. 'Deafening' means something so loud you can't hear anything

else, and 'silence' is the opposite, a lack of sound. But when the two words are combined,

they give a new meaning. Deafening silence means 'an absence of noise that cannot be

ignored'.

Although oxymorons might seem quite complicated, you probably already know

some, and perhaps even use oxymorons in everyday. Have you ever heard the

phrases, small crowd, going nowhere, or good grief? These are all commonly used

oxymorons that use contrasting words to create new meanings.

We know that a crowd is usually a large group of people rather than a small one,

that you can't actually be going nowhere, and we can see that good and grief are

contrasting words. Once you are able to spot common oxymorons like these, it should get

easier to identify and understand them when you come across them in literature.

35