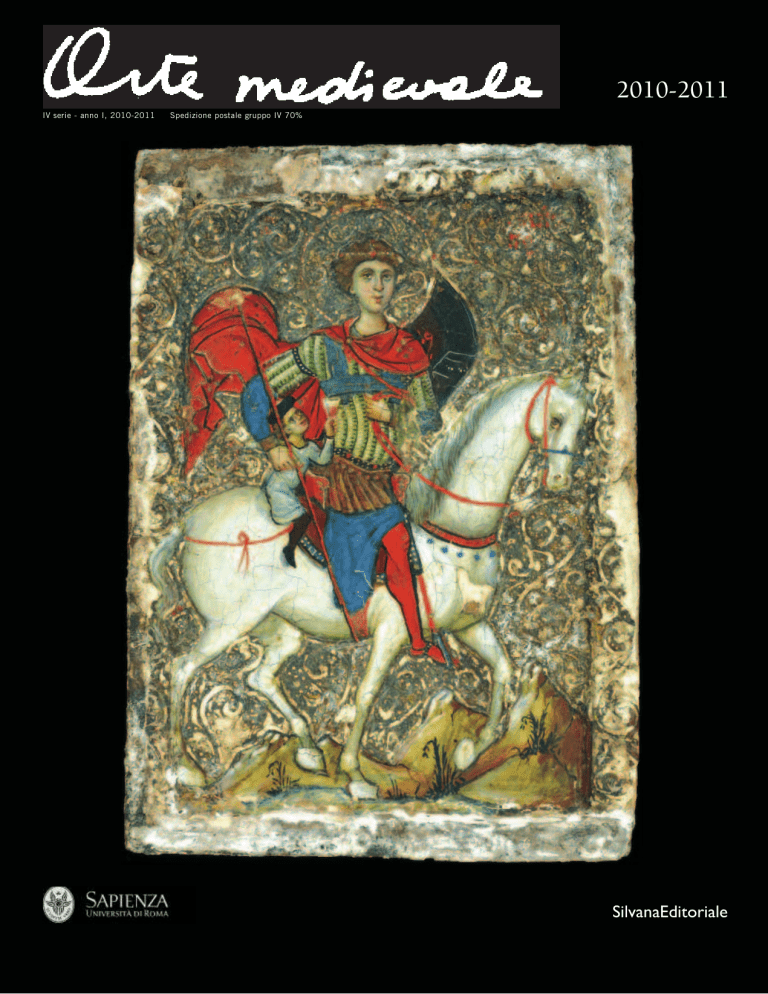

2010-2011 IV serie - anno I, 2010-2011 Spedizione postale gruppo IV 70% SilvanaEditoriale Lynley Anne Herbert DUCCIO’S METROPOLITAN MADONNA: BETWEEN BYZANTIUM AND THE RENAISSANCE Estratto dalla rivista Arte Medievale IV serie - anno I, 2010-2011 - pagine 97-120 DUCCIO’S METROPOLITAN MADONNA: BETWEEN BYZANTIUM AND THE RENAISSANCE Lynley Anne Herbert A tiny but complex work by the Sienese painter Duccio di Buoninsegna, previously known to scholarship as the Stroganoff or Stoclet Madonna,1 was purchased in November of 2004 for $ 45 million dollars by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York [1]. Commonly dated to c. 1300,2 this 8 1/4 by 11 inch painting (21 cm by 27,9 cm), which I will henceforth refer to as the Metropolitan Madonna, was hailed by the Metropolitan Museum as a work by one of the «founders of Western European painting».3 Such a view presents Duccio with the benefit of hindsight. Through the filter of the Renaissance, Duccio’s work is seen as art, and he as artist. The Metropolitan Museum’s press release claimed that with this painting, «Duccio has redefined the way in which we relate to the picture: not as an ideogram or abstract idea, but as an analogue to human experience».4 This formulation seems to frame a contrast with other images that are ‘abstract ideas’, and alludes to the common conception of the pictures called ‘icons’ in modern scholarship, pictures associated with the medieval and Byzantine tradition. Yet this is the very tradition upon which Duccio’s paintings build. Divorcing him from that, and setting up a strong dichotomy between Eastern, medieval «icons» and Western, Renaissance ‘art’ creates a false and violent break with tradition that Duccio himself would not have experienced.5 In this paper I will argue for new ways of understanding Duccio’s Metropolitan Madonna – not looking back from the Renaissance, but instead looking forward from a medieval and specifically Byzantine tradition, and ultimately at its context in Siena at the dawn of the 14th century. It is perhaps more appropriate to begin exploring this topic with a brief discussion of the painting in question.6 It depicts the Virgin Mary holding the Christ Child on her left arm, with an unusual row of architectural corbels running along the bottom of the image. As I will offer my own interpretation of this work below, I would like to first present some com- monly accepted views. Several scholars have understood the Virgin as standing behind a parapet,7 the meaning of which was most trenchantly explained by the wall text from the Metropolitan Museum’s 2005 exhibition of its newly acquired painting, which described it as «a device that simultaneously connects and separates the timeless, hieratic realm of the painting and the real space and time of the viewer».8 In his recent article about the acquisition, Keith Christiansen, the Metropolitan Museum’s Curator of European Paintings, suggested that the angle of the corbels relates to the intended viewing of the painting as one kneels in prayer.9 Scholars have tended to interpret the Child as playful, which they believed was a new invention by Duccio intended to show Christ in a more human, realistic way by creating a tender interaction between a mother and child as might be seen in life.10 In his article, Christiansen applied Hans Belting’s poetic assessment of this same gesture in Duccio’s Madonna di Crevole to the Metropolitan Madonna. Belting explained that Duccio: «…surprises us with the playful behavior of the Child, who grasps his Mother’s veil as if he wanted to distract her from her melancholy. Like the realism of the Child’s costume, the tender touch suggests a private idyll of the nursery…».11 Christiansen himself, in his recent book published by the Metropolitan Museum, suggests that the Child is «reaching up to push aside his mother’s veil so he can see her» which he believes was intended to strike «a chord so familiar as to make this image register as real».12 Another interpretation, by John White, considered this motif a «gesture of affection and communication» with which the Child comforts His mother in anticipation of her future sadness.13 Overall, this painting has been viewed as a creative, new, emotionally accessible interpretation of an outdated theme, and more importantly, a true work of art rather than a cult object whose functional aspect predominated over its emotional or aesthetic qualities.14 97 LYNLEY ANNE HERBERT 1. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Duccio di Buoninsegna, Metropolitan Madonna, c. 1300. The Metropolitan Museum’s enthusiasm for this painting is understandable. Although the cost was enormous, the Museum’s then Director Philippe de Montebello defended this extravagant expenditure by explaining that it fills a gap, and «the addition of the Duccio will enable visitors for the first time to follow the entire trajectory of European painting from its beginnings to the present».15 While some 98 reviewers cynically pondered better uses for the money,16 most faithfully characterized this as a landmark Renaissance painting by one of the first true great Western artists.17 The exhibition created around the Duccio at the museum emphasized this idea, and its place as one of the first expressions of Renaissance art seemed supported by the plethora of ‘Duccesque’ Madonnas grouped with it in the room, as well DUCCIO’S METROPOLITAN MADONNA: BETWEEN BYZANTIUM AND THE RENAISSANCE 2. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Icon with the Virgin Eleousa, early 14th century. Gift of John C. Weber, in honor of Philippe de Montebello, 2008. as the later works that followed in the adjoining gallery. Yet, permanently hung in an art gallery for the first time in its 700 years of existence, and treated as ‘art’, this small, intimate devotional painting almost appeared out of place, and had difficulty competing with the ornate altarpieces it is believed to have inspired. If Duccio inspired all of this, what inspired Duccio? He was not creating art in a vacuum. The Byzantine tradition was clearly influential to this painter’s work, yet there was no Eastern art, or even significantly earlier Western art displayed with the Duccio. The exclusion of such material denied the viewer the chance to make comparisons that would support the wall text’s assertion that «…the picture marks the transition from medieval to Renaissance image making».18 While this statement was rather vague, 99 LYNLEY ANNE HERBERT the press release was more precise, stating that «Duccio’s infusion of life into time-worn, Byzantine schemes» was probably influenced by popular devotional and love poetry, as well as Giotto’s frescoes, and that «it was an art that embraced the complex and varied world of human experience, rather than one based on codified types, as had been the case with medieval and Byzantine painting. Duccio responded by exploring in his own art this new world of sentiment and emotional response…».19 This emphasis on the newness of emotional and human qualities in these images, and the assertion that this was an ‘Italian’ invention of this period, is questionable. Far from being a Western novelty, this was more likely an aspect that was coming from the East, particularly during the Palaeologan era. This period saw the flowering of a poignant iconography characterized by scholars as the Mother of God Eleousa,20 or literally ‘Mother of Tenderness’ or ‘Merciful’, which was well established by the year 1300, as can be seen in a micromosaic at the Metropolitan Museum [2].21 The Metropolitan Madonna draws heavily on this type, as well as on the more formal iconography that scholars refer to as the Hodegetria,22 or ‘She who shows the way’, which was based on the famous icon in Constantinople that depicted Mary holding the Child on her left arm and presenting him to the worshipper. Duccio’s debt to Byzantine art has in fact long been recognized. James Stubblebine discussed the issue at some length in his 1966 article «Byzantine Influence in Thirteenth-century Italian Panel Painting».23 Stubblebine argued for a close, careful relationship between Duccio’s paintings and the contemporary artistic currents of the East, and in particular those coming from Constantinople. John White, in his 1979 monograph on Duccio, asserted that «at every stage of his career, the connections with Byzantine art are as visible as they are vital».24 Anne Derbes has further argued that there was an open and enthusiastic artistic reciprocity between the Sienese and the Levant during Duccio’s formative years.25 The current tendency to stress Duccio’s efforts to break with Eastern tradition within his Metropolitan Madonna is at odds with this earlier scholarship, to which it does not respond. However, even those who support a Byzantine connection tend to do so on an aesthetic, rather than functional, level. I would argue that we should not assume one aspect was adopted 100 without the other. Duccio’s work, and especially the Metropolitan Madonna, is strongly evocative of Eastern art, and of Byzantine icons. For Hans Belting an icon, or ‘Holy Image’, referred pre-eminently to the venerated «images of persons that were used in processions and pilgrimages and for whom incense was burned and candles were lighted».26 This included private icons, which were characterized by their small scale and emotional expressiveness.27 Duccio’s Metropolitan Madonna explicitly recalls this tradition. It is icon-like in its golden field, its emotive quality, and its small, portable size. It represents the ‘Holy Images’ of two people, both the Virgin and Christ, whose half-length portrait type was, according to Belting, reintroduced to the West from the East, and reflects the legend of the miracle-working authentic portrait that St. Luke painted of the Madonna and Child.28 I will argue below that the Metropolitan Madonna was in fact designed to retain something of that magical quality, and would likely have been considered apotropaic by its patron. We even know that the Metropolitan Madonna was actually used and venerated in the way that Belting associates with Byzantine icons, evidence for which is physically present in the burn marks left by centuries of candles having been lit along the bottom of the frame.29 No aspect of this painting would prevent it from being used or characterized as an icon. Perhaps rather than focusing on how Duccio disrupted this tradition, we should be asking how, and why, he embraced it. The main hesitation to view Duccio’s painting in this way appears to have been due to the place of its creation, and the nationality of its creator. That Duccio was Italian seems to have exempted him from the possibility that he might have desired to retain an iconic function in his work, and to exempt his patrons from desiring it. Of course, it must be remembered that much of what gives an image power lies in how it is viewed and used, and ultimately we cannot know the beliefs of its original owner of the panel who is, in any event, unidentified. However, one’s location or nationality need not be taken as defining beliefs. There was in fact a strong interest in, and belief in the power and importance of, Byzantine icons and imagery in the West in the 13th and 14th century. After the Latin invasion of Constantinople in 1204, Byzantine icons of all types flowed into Italy, and into Venice in particular. The church of S. DUCCIO’S METROPOLITAN MADONNA: BETWEEN BYZANTIUM AND THE RENAISSANCE Marco became, according to Belting, «a pilgrimage church of the Byzantine kind».30 Many of these images were seen as extremely powerful, even miraculous, and both original Eastern images and replicas of them were quickly disseminated throughout Italy.31 In Rome, a late 13th century Byzantine mosaic was given pride of place in a renowned reliquary at the Basilica di Santa Croce in Gerusalemme.32 At least one Byzantine icon was in Siena by the time Duccio was painting, for a 13th century icon of the Madonna and Child, inscribed «Mother of God» in Greek, belonged to the Chiesa del Carmine.33 Paintings and manuscripts known in scholarship as «crusader art», works produced in Eastern provinces for the Crusaders that often blended Eastern and Western iconography, were also circulating throughout the West.34 Hayden Maginnis has argued for an increasingly miraculous view of images in the West after 1200, which he attributed to the Western presence in Crete, Cyprus, and Constantinople. He suggested this exposure both led to the «absorption of Eastern thought» and «influenced expectations of how images might behave».35 There were numerous accounts of the miraculous activities of icons in Italy at that time. For instance, the possibility of interacting with an image’s prototype through the image itself was not only believed in, but also actively promoted through saints’ legends. St. Francis’ conversion due to the miraculous intervention of Christ through a painted crucifix was a wellestablished tale by the time Duccio was working.36 This miracle was actually absent from Thomas of Celano’s original account of Francis’ life, and in fact only appeared in the second Life of 1240, written 35 years after the event would have taken place.37 The addition of this story in the later revision perhaps indicates an increased interest in and acceptance of the power of images in Italy by the mid 13th century. St. Catherine was also converted due to her contemplation of a panel painting through which she interacted with the prototypes, and in that case it was the Madonna and Child.38 An icon of Christ in Venice even bled when it was cut with knives in 1290.39 Most of the image types circulating in Italy at this time either drew upon or claimed to be Eastern art. Eastern images were not treated just as booty, or curiosities, but were instead often given more authority than Western images. Venice even adopted the 11th century Constantinopolitan icon they called the Nicopeia, taken during the siege on Constantinople and credited with the Latin victory, as its palladium.40 Eastern images were intentionally used or referred to, and for a reason – it was believed they had immense spiritual power.41 Harnessing that power would have been an important goal for the painter and his patron. The desires of the patron are an important issue to consider here, for since Duccio depended on commissions for his livelihood, he would have had to adhere to their demands. Therefore, to read into the Metropolitan Madonna modern ideas about artistic creativity, wherein the artist tries to break free of convention and do something radically new, is problematic and anachronistic. As Anthony Cutler has succinctly put it, «until the 16th century none of the cultures to which we have referred ‘conceived’ [his emphasis] of originality in our sense, let alone thought it virtuous».42 This is not to say that artists could not be innovative, only that their form of creativity may not fit our modern conceptions. The supposedly unique elements of this painting warrant a closer examination. The Child’s gesture has been seen as a new invention with which Duccio was experimenting, thought to convey the human interaction between a playful child and his mother and viewed as a realistic detail taken from life experience.43 I would argue, however, that Duccio was doing something very different. As John White pointed out, the Child appears to be comforting the Virgin in her sadness.44 Duccio was working with a Byzantine type, that of the lamenting mother of the Threnos, known in Italy as the Mater Dolorosa or ‘Mother of Sorrows’, but used it in a new way. Compare, for instance, Duccio’s Madonna with that from one of Cimabue’s late 13th century crucifixes [3].45 Note the inclination of her head, as well as the bunched cloth that she holds to her eyes. Although here the cloth is a separate element, there are other instances, such as a c. 1300 Venetian triptych now in a private collection in Dordrecht, where she uses her very veil to dab her eyes.46 The similarity of her pose and gesture to that found in the Duccio painting is uncanny, only Christ’s hand has replaced Mary’s in holding the cloth to her eyes to catch her tears, the future event recognized by Him in His omniscience. 101 LYNLEY ANNE HERBERT 3. Arezzo, San Domenico. Cimabue, Crucifix, detail, the Virgin Mary. The recognition of and intentional interplay between the Mother and Child and the Mother of Sorrows had a strong artistic and linguistic tradition in the Byzantine world. Constantinople’s most famous icon, the Hodegetria, was double-sided and depicted the Virgin and Child on one side, and the Crucifixion on the other.47 In literature, the connection was explicitly made in the Virgin’s lament in the Greek recension of the Acta Pilati.48 Similar concepts in texts and art had been transmitted to Italy by the 13th century, as Anne Derbes and Rebecca Corrie have demonstrated.49 A close parallel to the iconography of the Constantinopolitan Hodegetria can in fact be found in an Umbrian diptych from 1260 [4].50 That Duccio understood this relationship is unquestionable, for he 102 visibly juxtaposed the two events in his early 14th century triptych of the Crucifixion [5]. The position of Mary’s head and the expression on her face are nearly identical in both of her roles as new mother and Mother of Sorrows. I propose that Duccio was trying to create an image of deeper meaning by combining several Byzantine image types, for in this image can be found the formality of the Hodegetria, the tenderness of the Eleousa, and what I perceive to be the foreshadowed compassion and sadness of the lamenting mother of the Threnos. Its poignancy is heightened by the Child’s loving gesture, and certainly this interpretation, tracing Duccio’s inventive manipulation of various sources, does not detract from, but rather adds to, Duccio’s accomplishment. However, those DUCCIO’S METROPOLITAN MADONNA: BETWEEN BYZANTIUM AND THE RENAISSANCE 4. London, The National Gallery. Virgin and Child and the Man of Sorrows, diptych, c. 1260. 5. London, The Royal Collection of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II. Duccio di Buoninsegna and workshop, Crucifixion with Mary and John, c. 1308-1311. 103 LYNLEY ANNE HERBERT who wish to view this as a Renaissance painting may not agree, for this form of creativity may have more in common with medieval artistic practices, where painters worked from received traditional types rather than directly from ‘nature’. Recent scholarship has begun to recognize similar inventive reuse and recombination of Byzantine image types in Duccio’s Tuscan predecessors. Rebecca Corrie has argued that Coppo di Marcovaldo, when painting the Madonna del Bordone for Siena in 1261, «brought together a group of motifs derived from Eastern images whose meanings and power he and his clients understood».51 A similar argument has been made for Cimabue’s painted crucifixes by Anne Derbes, who claimed that «much that is new here stems not from Cimabue’s success in liberating himself from Byzantium, but rather from his appreciative study of images recently introduced from Byzantium».52 While still creating something new and of artistic value, these artists ultimately chose to integrate specific Eastern image types into their work, and I suggest that Duccio was consciously working within this tradition. The final and most distinctly different element in this painting, the so-called ‘parapet’, has been the subject of much discussion.53 In 1979 John White set the tone: «…it now stands as the first, lonely forerunner of that long line of Italian Madonnas with a parapet which achieved its finest flowering almost two centuries later in Giovanni Bellini’s splendid variations on the theme».54 Hindsight is not always reliable. A comparison of Duccio’s Madonna and Bellini’s paintings reveal they have little in common, for Bellini went to great lengths to situate his Madonna and Child figures into an actual spatial setting with a background [6]. They interact with the architectural ledge, which is entirely different from Duccio’s both in its perspective and in its symbolism as an altar-tomb.55 Can we really read meaning back into Duccio’s painting based on something Bellini would do two hundred years later? Would the average Trecento Sienese citizen have interpreted Duccio’s architecture in this way? Victor Schmidt and Keith Christiansen have offered examples of panels with what they view as similar architectural elements running along the bottom,56 both pointing for instance to Simone Martini’s Saint John the Evangelist. However, 104 Martini’s painting comes two decades after Duccio’s, and the ledge along the bottom is both visually completely different, lacking the corbel motif, and contains an inscription, thereby taking on a different function. In fact, none of the suggested comparisons date earlier than this, leaving a generational gap between Duccio’s work and anything similar, works that even then do not use the corbels we see in Duccio. I would argue that a seemingly similar motif’s use at a later date is not proof of Duccio’s intentions. Are there other ways of understanding the corbelled ledge in the Metropolitan Madonna? It seems to invoke the da sotto in su effect so often used in Italian painting to create the illusion of seeing something from below, yet this painting is much too small to be set up high enough for this effect to have worked correctly.57 The motif itself was consistently employed by painters to convey architecture at a great height, often as a cornice indicating the top of a wall or the bottom edge of a roof. That this illusionistic device was understood and used in this way can be demonstrated both before and after Duccio painted his Metropolitan Madonna around 1300. In the 13th century this architectural element was used in the frescos often attributed to Giotto in the church of St. Francis in Assisi, such as in the Dream of pope Innocent III [7]. Here the same painted corbels have been used to indicate height in two ways – both in the faux architecture high on the wall of the church above which the fresco itself was placed, as well as in the cornice of the church Saint Francis holds within the painting. Many of the frescos in Assisi use this architectural motif, and their height allows it to be viewed more or less at the correct perspective. Scholars often compare Duccio’s motif to that used in Assisi since they are confident he visited there, and if in fact he did, he would have seen it in use.58 Another example of this type of illusion can be found slightly later in the work of an anonymous artist, known as the Master of Badia a Isola [8]. Dated between 1310-1320, this large lunette of a Madonna and Child, measuring 124 by 147 cm (or about 4 by 5 feet), has painted consoles that not only run along the bottom, but along the arch as well, and were presumably intended to allow the panel to appear attached to the architectural setting for which it was originally made.59 The use of faux consoles was therefore DUCCIO’S METROPOLITAN MADONNA: BETWEEN BYZANTIUM AND THE RENAISSANCE 6. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Robert Lehman Collection, 1975. Giovanni Bellini, Madonna and Child, c. 1470. understood here as an architectural setting, not as a balcony or parapet. Duccio used this customary architectural motif differently from the artists in the above examples due to the small scale of his works in which it appears. If we look at his most celebrated work, the Maestà, he provided clues as to his own ideas about the application of this motif. Although it was begun in 1308, which is probably slightly later than the Metropolitan Madonna, the Maestà is the only major example of Duccio’s use of architecture, and it is also his only signed work. This altarpiece in fact contains a number of small panels depicting the type of architecture that is found in the ‘parapet’. Only one of these includes corbels in a balcony-like setting, and that is in the Temptation on the Temple. However, in the panels depict105 LYNLEY ANNE HERBERT 7. Assisi, upper church of St. Francis. Attributed to Giotto, the Dream of pope Innocent III, c. 1297-1299. ing the Teaching in the Temple [9], and Judas Taking the Bribe, the painted consoles, which here are almost identical in both angle and style to those in the Metropolitan Madonna, have been used to designate the top of a wall, or the bottom edge of a roof - ‘not’ spaces where someone stands. In these, then, Duccio was 106 using a miniature form of a monumental motif to signify architecture at a great height. If we view the ‘parapet’ of the Metropolitan Madonna in light of Duccio’s own later work, it is not clear that this architecture refers to a balcony or parapet. What other purpose might this device serve? Although one could argue that he DUCCIO’S METROPOLITAN MADONNA: BETWEEN BYZANTIUM AND THE RENAISSANCE 8. Montepulciano, Museo Civico. Master of Badia a Isola, Virgin and Child between Two Angels, c. 1310-1320. was experimenting, I must stress again that his freedom of expression would only have gone so far. The Metropolitan Madonna was commissioned by someone for his or her personal use, and the patron would have been paying for each element.60 Therefore, the cornice motif must have fulfilled some desired effect requested by the patron, or at least must be thought of in that context. As I mentioned above, the obvious, and most likely correct, comparison has been consistently drawn between Duccio’s painted consoles and those found at Assisi. The comparison is convincing, and yet making this identification of his motif’s possible source really does not offer any explanation for what it means to the painting. Only one image known to me appears to employ this architectural element in the same way as Duccio’s, and it is a marian icon from the 13th century in S. Marco, Venice, known now as the Madonna del latte [11]. Considered to be from either a Veneto-Byzantine or Tuscan school, it strongly recalls Byzantine art, especially in the Virgin’s gesture.61 Its similarities to the Metropolitan Madonna are minimal, for the Madonna del latte is surrounded by saints62 and holds Christ on her right arm while nursing him. It is also extremely large, measuring 67 by 50 inches (170,18 cm by 127 cm). However, the ‘parapet’ at the bottom is intriguingly similar, and it uses remarkably similar corbels and is even angled to offer the effect of looking at it from below and to the left, just as Duccio’s painting does. Could Duccio have seen this painting, and been inspired by it? It is possible, since it is believed he spent seven years traveling,63 and if he was interested in Eastern art forms, S. Marco was a major pilgrimage church that would have given him access to a wide variety of Byzantine images. It is also quite likely that there may have been other, now lost images circulating in Italy that employed a similar device.64 As the Venetian icon appears to be the only other surviving panel to include this same architectural motif, however, I searched for explanations for this work’s ‘parapet’. It is striking that while this painting’s architecture is virtually the same as the Duccio, I have found no suggestion that it represents a balcony. The two exhibition cat107 LYNLEY ANNE HERBERT 9. Siena, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo. Duccio di Buoninsegna, Maestà, Teaching in the temple, c. 1311. 108 alogs in which the Madonna del latte appeared simply stated that the architectural element was an unusual feature in this type of painting.65 Victor Schmidt suggested it may have been mounted within the church, and that the corbels may possibly have been continued on the wall as a sort of faux architecture.66 Belting’s explanation, however, was that Eastern panel paintings were meant to be hung, and illequipped to sit on the altar of the Western church, therefore leading to improvised ways to make the image transition between painting and mounted altarpiece.67 While either of these might offer a feasible explanation for the large S. Marco image, they are not convincing when applied to Duccio’s painting. As a newly made private piece for the home, it had no need for modifications to accommodate an altar, something it is doubtful the donor would have had.68 I was not, however, the only one to notice the similarity of this strange feature in these two paintings. Schmidt drew the comparison in his recent book, but felt that the similarity was superficial and that the architecture did not serve the same function due to the difference in size and function of the paintings.69 Mojmir Frinta, however, in his 1987 article Searching for an Adriatic Workshop with Byzantine Conne- DUCCIO’S METROPOLITAN MADONNA: BETWEEN BYZANTIUM AND THE RENAISSANCE 10. Siena, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo. Madonna degli occhi grossi, mid 13th century. ction, mentioned the two paintings in a footnote, and suggested the architectural element might refer to the tradition of attaching palladia above the gates in Constantinople70 and may be a record of a famous image in that type of installation.71 He went no further with his thought, and did not explore how this worked with these images. Could he have been right? And if so, how might we interpret Duccio’s painting from this vastly different point of view? At first it seems unlikely that this tiny Sienese painting would make such a reference. 109 LYNLEY ANNE HERBERT 11. Venice, S. Marco. Madonna del latte, 13th century. 110 However, one unusual element of this painting, never discussed in any depth,72 may lend support to this possibility. I refer to the faintly etched decorative inner border, now very much faded along with the rest of the gold. I would argue, in fact, that it is highly important; I propose it acts as a frame within a frame. If so, it may indicate that this painting is meant to be read as an image ‘of’ an image, which would further support the possibility that Duccio was referring to another painting. Although such decorative borders are not unknown in panel paintings, Duccio’s incised design is very distinct, and corresponds closely to actual frame decoration of the time. It is comprised of alternating lozenges and floriated vines, each divided from the other by rectangular bars. The closest parallels for this type of decoration all fall within the Crusader art tradition.73 Crusader icons and manuscript illuminations often combine lozenges and floral designs on their frames.74 For example, there is a Cypriot icon of the Mother of God Arakiotissa, dating from the late 12th century, that has lozenges divided by bars along the sides, with a vine pattern, now barely visible, along the top and bottom.75 A similar border pattern can be found in a late 13th century manuscript illumination of the Crucifixion from Acre, the capital of the Latin kingdom of Jerusalem.76 Dating to the third quarter of the 13th century, this miniature’s frame intersperses the lozenge and vine motifs. A third Crusader image, an icon of Saint George from Lydda or possibly Cyprus, dates from the mid 13th century and employs raised gesso vine patterns on both its frame and its background [12]. These distinctive floriated vines are nearly identical to those Duccio inscribed into the inner ‘frame’ of the Metropolitan Madonna, and similar types can be found in many other Crusader images. Athanasios Papageorgiou argued that since the specific combination of geometric and plant motifs appeared in both Crusader icons and Syriac manuscripts, it was probably coming to the West from Constantinople.77 Whether or not this Constantinopolitan origin is accepted, the combination of lozenges and vines may have signified an intentional and desired connection with the East. Thus, with a subtle scrawled design and a simple illusionistic architectural effect, employed as a sign rather than as realistic perspective, Duccio was able to allude to the grandeur of the Constantinopolitan icon of the Virgin protectively set up upon the gates, and more importantly, to imbue this tiny painting with an immense amount of power for its owner.78 Why would an upper-class Italian living in Siena want such a reference in their home’s devotional image? It appears that the answer to this question lies in Siena’s own history. The often cited account by Niccolò di Ventura, who wrote of Siena’s history in the 1440’s, claimed that when the city was under siege by the Florentines in September of 1260, one of its citizens, Buonaguida, gathered the people together and went to the cathedral.79 There the bishop joined him, and the two went and knelt, and in fact Buonaguida prostrated himself, before the Madonna degli occhi grossi on the cathedral’s altar [10]. They prayed, and Buonaguida asked for the Virgin to protect Siena, vowing to dedicate the city to her in return.80 The battleground was veiled with a mysterious white mist, and the next day, the Sienese defeated the Florentines in the battle of Montaperti.81 DUCCIO’S METROPOLITAN MADONNA: BETWEEN BYZANTIUM AND THE RENAISSANCE The details of this story may very well be later fabrications, as no contemporary accounts survive.82 There was, however, a historic battle at Montaperti against the Florentines, and the Sienese victory was a source of pride for centuries to come.83 It has come down through history, via authors such as Niccolò di Ventura, that from 1260 on the city of Siena was believed to be under the Virgin’s protection.84 Rebecca Corrie has convincingly argued that a painting signed and dated 1261 by Coppo di Marcovaldo, known as the Madonna del Bordone, was meant to commemorate the victory over the Florentines as well as Siena’s amplified relationship with the Virgin [13].85 A drastic iconographic shift occurred here. The earlier Madonna degli occhi grossi was of a type derived from Romanesque Maestà sculpture - frontal, enthroned, and in slight relief.86 It is interesting to note that at least two large Madonnas of this type were made in Florence around 1260, where it was a popular form of marian imagery. Perhaps the Ghibelline Sienese were reacting against the images preferred by their enemy, Guelph Florentines, for suddenly the Sienese created an entirely different Madonna to celebrate their victory over Florence: a panel painting that corresponded to the Byzantine image type referred to in art historical literature as the Hodegetria.87 That the Sienese would choose the famous Hodegetria of Constantinople as their model is not so strange. In Images of the Mother of God, Michele Bacci explained that by the 12th and 13th centuries the fame of the Hodegetria was widespread outside of Constantinople, and many cities not only copied the painting but also the rituals and miraculous properties associated with 88 it. This led to what Bacci termed the «cult of 89 Constantinople’s palladium» in Italy. Rebecca Corrie related this phenomenon to Siena: «Byzantine art as the style of the major Mediterranean capitals may have been of particular interest to cities on the rise, such as Siena after Montaperti. A desire to rival other Mediterranean capitals, and Constantinople in particular, might have furthered Siena’s imitation and importation of Byzantine and Byzantinizing art».90 She went on to suggest that «the use of some Byzantine elements in their image of the Virgin and Child might have been a means of associating Siena with Constantinople directly».91 When this idea is viewed in concert with other aspects of Siena, a possibility emerges that they were intentionally fashioning themselves after Byzantium’s greatest city. William Bowsky pointed out the striking similarity between the name of Siena’s financial magistracy, the Biccherna, and Constantinople’s public office district called the Blachernae, which he suggested was intentional.92 The Sienese city seal depicted the Virgin and Child, as did the imperial seal of Constantinople.93 Furthermore, Annemarie Weyl Carr has pointed out that the use of the Virgin’s veil as a topos for her protection, an idea with long roots in Constantinople, was in use in Siena, for she has suggested that the white veil worn by Sienese Virgins is a reference to the protective white mist that veiled the battle of Montaperti.94 The most compelling evidence of emulation, at least for our purposes, is the fact that the Sienese placed painted images of the Virgin on their city gates. Although imagery was also 12. London, British Museum. Crusader icon of Saint George and the youth of Mytilene, mid 13th century. 111 LYNLEY ANNE HERBERT 13. Siena, S. Maria dei Servi. Coppo di Marcovaldo, Madonna del Bordone, 1261. 112 DUCCIO’S METROPOLITAN MADONNA: BETWEEN BYZANTIUM AND THE RENAISSANCE employed over the gates of some other cities such as Florence, Julian Gardner and Felicity Ratté have pointed out that Siena was distinct in using only painted imagery instead of sculpture, which was more common.95 Ratté especially contended that these must have had an apotropaic quality, echoing the earlier words of Judith Hook: «Paintings of the Virgin on the city-gates, like those at Camollia and Porta Romana, were placed there to provide a magical defense at the city’s weakest points, for, if the Virgin was Queen of Siena, she had certain obligations towards her city, including that of defending it from its enemies».96 Records survive in the Archivio di Stato di Siena that provide evidence of the Virgin gracing four of the gates, and Gardner has stated that every gate bore her image following the victory of Montaperti.97 The earliest surviving record is a commission from 1309, designating two artists to paint the Virgin and saints on the Porta Camollia, which was one of the main entrances into the city. However, a carpenter was also included in the commission, and his task was to ‘repair’ the roof over the image.98 It is logical, then, that there may have been an image there previously since the roof already existed, and its function was to protect the painting from the elements. Records show that the image on the Porta Camollia was maintained through repainting over the course of at least the next fifty years, with repairs made in 1333, 1346, and 1362.99 The shortest period of time between these is thirteen years. Therefore, if the commission of 1309 was for a ‘repainting’, it is likely that the original image would have already been in place before 1300. This possibility is further supported by the fact that the antiporta for the Porta Camollia was completed by 1270, therefore allowing ample time for an NOTES I am deeply grateful to Dr. Lawrence Nees of the University of Delaware for his endless support and guidance, and to Dr. Anne Derbes for offering her advice and encouraging me to pursue these ideas. I would also like to thank Dr. Gary Vikan and the Walters Art Museum for providing financial support for this publication. This painting, having no known original title, is referred to by the names of its two documented owners. The 1 image to be installed before Duccio painted his Metropolitan Madonna.100 In their very specific use of the Virgin and Child imagery, the Sienese were intentionally invoking the most powerful icon of the Virgin known at that time – one that had protected the great city of Constantinople for centuries, and one that still held power in 1261 when the Latin occupation ended, and the Hodegetria was triumphantly processed through the streets of the city.101 By the time Duccio was painting his Metropolitan Madonna, the imagery of the Hodegetria type was firmly in place in Siena as the city’s protectress and ruler. I propose, therefore, that Duccio’s Metropolitan Madonna is the product of this civic marian cult. Much as the Sienese as a whole seem to have done, Duccio may have combined his own city’s protective Virgin with the greatest and most powerful palladium of all, the Hodegetria of Constantinople. This was the ultimate miracle icon, both in its origin as a painting by Saint Luke102 and in its apotropaic quality, and Duccio found a way to recreate it for personal use, deftly increasing his version’s potency, and counterbalancing its small scale, by depicting it in its traditional protective position above the gates.103 In conclusion, the interpretations I have put forth squarely place this painting into the realm of the icon, for they mean Duccio was consciously and intentionally referring to and recreating both established Byzantine images and monumental paintings in Siena in order to retain their power and meaning. Although we may never know for sure what Duccio intended, or how this image was actually used, I hope to have at least demonstrated that the accepted ideas about the Metropolitan Madonna are not the only possible interpretations, and that perhaps it is us, not Duccio, who must break free of convention. Metropolitan Museum’s press release states it is most commonly known as the Stroganoff Madonna after its first recorded owner, Count Grigorii Stroganoff. However, the painting is also known by the name of Adolphe Stoclet, the man who purchased it after Stroganoff’s death in 1910, and whose family sold it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Although the museum has chosen to title the piece simply Madonna and Child, I have decided for clarity to refer to it here as the Metropolitan Madonna. For the press release, see Metropolitan Museum of Art, Early Renaissance Masterpiece by Duccio Acquired by Metropolitan Museum, 113 LYNLEY ANNE HERBERT press release (November 10, 2004), p. 1. This can be found on the museum’s website in the «Press Room» - Press Release Archive, November 2004. Available: www.metmuseum.org/Press_Room/full_release.asp?prid. 2 J. WHITE, Duccio: Tuscan art and the medieval workshop, New York 1979, p. 63, dates it to 1295-1300; Metropolitan Museum of Art, Early Renaissance Masterpiece, p. 2, dates it to c. 1300; K. CHRISTIANSEN, The Metropolitan’s Duccio, «Apollo», CLXV (2007), pp. 40- 47: 47, suggests a broader range of 1295-1305. 3 Metropolitan Museum of Art, Early Renaissance Masterpiece, p. 2. 4 I will be quoting from two sets of wall text from the Duccio exhibition – one which was the main text to introduce the exhibition, and one which labeled the Metropolitan Madonna itself. Both are available online. The quote I have included here is from the Metropolitan Madonna wall text, which can be found on the museum’s website: Duccio di Buoninsegna: Madonna and Child (2004.442), in «Timeline of Art History», available: http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/ho/07/eust/hod_2004. 442.htm. The main texts about Duccio and his time that introduced the visitor to the exhibition are also available online, at http://www.metmuseum.org/special/Duccio/ duccio_more.htm#4. 5 Indeed, Hans Belting did term Duccio’s paintings ‘icons’. H. BELTING, Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image Before the Era of Art, trans. E. Jephcott, Chicago 1994, p. 370. 6 It should be noted, however, that the Metropolitan Madonna has been mostly inaccessible until its purchase by the Metropolitan Museum in 2004, for it was still in private hands, and only a turn-of-the-century black-and-white photograph of it was known. Consequently, it shows up in very few discussions of Duccio’s paintings, and most other discussions draw on these few. The fundamental publications, with earlier literature, are two influential monographs written in 1979, one by John White, referred to in note 2 above, and another by J. H. STUBBLEBINE, Duccio di Buoninsegna and his school, Princeton 1979. Only recently has new information been published, primarily by the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Curator of European Paintings, Keith Christiansen. See CHRISTIANSEN, The Metropolitan’s Duccio, pp. 40-47, and ID., Duccio and the Origins of Western Painting, New York 2009. 7 Duccio exhibition wall text (see note 4). The text states that «The Madonna is shown as though standing behind a parapet». Other authors who have spoken of it in similar terms are WHITE, Duccio, p. 62. He states that «it now stands as the first, lonely forerunner of that long line of Italian Madonnas with a parapet»; STUBBLEBINE, Duccio di Buoninsegna, p. 28, says the parapet imposes a specific viewpoint on viewer, and also removes the Madonna and Child from space of the viewer. He connects this motif to those by Giotto in Assisi; Duccio: alle origini della pittura senese (exhib. cat. S. Maria della Scala, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Siena, Oct. 4, 2003-Jan. 11, 2004), a cura di A. Bagnoli, Milano 2003, p. 136. This exhibition catalog equates the parapet to a windowsill supported by a row of consoles, and also relates it to Giotto and Assisi. 8 Duccio exhibition wall text. Victor Schmidt has recently expanded the discussion of this element of the painting, although he argues for the same interpretation. See V. 114 SCHMIDT, Painted Piety: Panel Paintings for Personal Devotion in Tuscany, 1250-1400, Firenze 2005, pp. 141158. See also CHRISTIANSEN, Duccio, pp. 50-52 for the most recent discussion of this, which expands upon the wall text and offers similar arguments to Schmidt’s. 9 CHRISTIANSEN, The Metropolitan’s Duccio, p. 46. 10 STUBBLEBINE, Duccio di Buoninsegna, p. 28; B. HEAL, ‘Civitas Virginis’? The significance of civic dedication to the Virgin for the development of Marian imagery in Siena before 1311, in Art, Politics and Civic Religion in Central Italy, 1261-1352: Essays by Postgraduate Students at the Courtauld Institute of Art, ed. J. Cannon and B. Williamson, Aldershot 2000, pp. 295-305: 300; CHRISTIANSEN, Duccio, p. 55. 11 BELTING, Likeness and Presence, p. 370, as quoted in CHRISTIANSEN, The Metropolitan’s Duccio, p. 44. 12 CHRISTIANSEN, Duccio, p. 55. 13 WHITE, Duccio, p. 24. White believes Duccio may have invented this gesture. He discusses it more in terms of the gesture found in the Crevole Madonna, which is essentially the same as that found in the Metropolitan Madonna, and sees it as Christ acknowledging his future passion, and his mother’s intuition of it because he reaches up to comfort her. However, the main reason he gives for reading it this way is that the red color under her veil, which he touches, alludes to the blood he will shed later. This red color is not repeated in the Metropolitan Madonna, however. 14 BELTING, Likeness and Presence, pp. XXI, 458-490. If we consider Hans Belting’s influential view, thinking of Duccio’s painting this way would be highly anachronistic, for he has argued that art as we think of it did not begin to be produced for another two hundred years. 15 Metropolitan Museum, Early Renaissance Masterpiece, p. 1. 16 G. L O N E Y , $45 Million ‘Stroganoff Madonna’ on View, «Curator’s Choice», January (2005), http://www.nymuseums.com/lm04124t.htm. Loney points out, «This staggering sum for a small piece of wood has been paid out of the Met’s Acquisitions Fund. They could have bought a lot of Andy Warhol prints for that money. Or even a small collection of Pre-Raphaelite paintings by Burne-Jones and others of his ilk». 17 This raises an interesting question: why is the Metropolitan Museum of Art referring to c. 1300 as the start of the Renaissance, as they do imply in the title of their press release? This view is one perpetuated by Giorgio Vasari, as in his The Lives of the Artists: Volume I, trans. G. Bull, Baltimore 1987, pp. 45-81, and has long since been reevaluated, with the Renaissance usually having its inception in the Quattrocento. This dating is typical in modern scholarship, such as in D. NORMAN, Painting in Late Medieval and Renaissance Siena, 1260-1555, New Haven 2003, in which Norman gives the starting date of 1420 to her chapter on «Renaissance Painting in Siena». It has literally become the textbook definition of Renaissance dating, as can be found in F. HARTT, History of Italian Renaissance Art: Painting, Sculpture, Architecture, New Jersey 1994, pp. 104-132, where Hartt places Trecento Sienese art into his chapter on the «Late Middle Ages». In fact, the Metropolitan Museum’s own timeline on its website places Duccio in the later Middle Ages, and as an example of «Private Devotion in Medieval Christianity», not the Renaissance. Under Department of European Paintings, see Italian Painting of DUCCIO’S METROPOLITAN MADONNA: BETWEEN BYZANTIUM AND THE RENAISSANCE the Later Middle Ages, in Timeline of Art History, http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/iptg/hd_iptg.htm. It is strange that in their press release and initial discussions of the Duccio acquisition, the museum perpetuated earlier narratives such as Vasari’s, in which artists such as Duccio and Giotto are promoted as the Renaissance’s founding fathers. 18 Duccio exhibition wall text. 19 Metropolitan Museum, Early Renaissance Masterpiece, p. 3. 20 Many images exist that were originally inscribed ‘Eleousa’ by their makers, and not all are in the same pose but rather carry the same sentiment. Examples of these can be found in the exhibition catalog Mother of God: Representations of the Virgin in Byzantine Art (exhib. cat. Benaki Museum, Athens, 2000), ed. M. Vassilaki, Milan 2000, nos. 67, 69, 73, 75, 76, 80. 21 The small icon referred to here was on display at the Metropolitan Museum, one floor below the Duccio exhibition. This work, a delicate micro-mosaic dating to the early 14th century and considered to be Constantinopolitan, offers a remarkably strong parallel to the Duccio Madonna. In light of the numerous parallels of both composition and feeling between the two images, and the fact that their creators were contemporaries, it is surprising that the mosaic was not included in the Duccio exhibition, although it might have challenged rather than supported the assertion that Duccio was doing something revolutionary. At the very least, the absence of the mosaic prevented viewers from making the comparison and coming to their own conclusions. 22 This term ‘Hodegetria’ specifically refers to the icon of the Virgin and Child housed in the Hodegoi church in Constantinople, which was venerated for its miraculous qualities, and which is believed to have depicted the Virgin with Christ on her left arm. However, the term has also come to be used in modern scholarship to describe images similar to this miraculous painting, and it is important to note that this was not a label used with any consistency in the Medieval era. For a clear and concise explanation of this issue, see R. MANIURA, Pilgrimage to Images in the Fifteenth Century: The Origins of the Cult of Our Lady of Czestochowa, Woodbridge 2004, pp. 23-24. Maniura explains it best by suggesting, «These labels must be seen as epithets attaching to the Virgin herself and not a formal image type». 23 J.H. STUBBLEBINE, Byzantine Influence in ThirteenthCentury Italian Panel Painting, «Dumbarton Oaks Papers», XX (1966), pp. 85-102: 99-100. 24 WHITE, Duccio, p. 57. 25 A. DERBES, Siena and the Levant in the Later Dugento, «Gesta», XXVIII (1989), pp. 190-204. 26 BELTING, Likeness and Presence, p. 3. 27 Ibid., p. 262. 28 Ibid., p. 58. 29 Metropolitan Madonna wall text. 30 BELTING, Likeness and Presence, p. 203. 31 Ibid., p. 330. 32 C. BERTELLI, The Image of Pity in Santa Croce in Gerusalemme, in Essays in the history of art presented to Rudolf Wittkower, ed. D. Fraser, H. Hibbard & M.J. Lewine, London 1967, pp. 40-55. Most recently, see R. CORMACK, M. VASSILIKI, Byzantium, 330-1453, London 2008. 33 BELTING, Likeness and Presence, p. 341. For more on the very complicated issue of Crusader art of this period, see J. FOLDA, Crusader Art in the Holy Land, from the Third Crusade to the Fall of Acre, 1187–1291, New York 2005. In ibid., p. 526, he points out that while we know this art, and especially icon paintings, played an important role in transmitting Eastern ideas and had a strong impact on Western art of this time, the exact process of transmission has yet to be sorted out fully. See also R. CORRIE, Coppo di Marcovaldo’s Madonna del bordone and the Meaning of the Bare-Legged Christ Child in Siena and the East, «Gesta», XXXV (1996), pp. 43-65. 35 H.B.J. MAGINNIS, The World of the Early Sienese Painter, trans. of the Sienese Breve dell’Arte dei pittori by G. Erasmi, University Park, Pennsylvania 2001, p. 169. For a fascinating new discussion of the interaction between people, images, and their prototypes, with possible roots in the Mediterranean but enacted in Siena during Duccio’s time, see J. CANNON, Kissing the Virgin’s Foot: Adoratio before the Madonna and Child Enacted, Depicted, Imagined, «Studies in Iconography», XXXI (2010), pp. 1-50. 36 THOMAS OF CELANO, First and Second Life of St. Francis, trans. P. Hermann, Chicago 1962. 37 MAGINNIS, The World of the Early Sienese Painter, p. 167. 38 For an excellent discussion of Catherine’s story and its relationship to art, see V.M. SCHMIDT, Painting and Individual Devotion in Late Medieval Italy: The Case of St. Catherine of Alexandria, in Visions of Holiness: art and devotion in Renaissance Italy, ed. A. Ladis and S. E. Zuraw, Athens, Georgia 2001, pp. 21-36: 21-22. 39 BELTING, Likeness and Presence, p. 197. 40 Ibid., p. 203. 41 Ibid., pp. 305, 348-352. 42 A. CUTLER, Originality as a Cultural Phenomenon, in Originality in Byzantine Literature, Art, and Music: a collection of essays, ed. A.R. Littlewood, Oxford 1995, pp. 203216; repr. in Byzantium, Italy and the North: Papers on Cultural Relations, London 2000, p. 36. Citations are to the London edition. 43 A.W. CARR, Threads of Authority: the Virgin Mary’s Veil in the Middle Ages, in Robes and Honor: the Medieval World of Investiture, ed. S. Gordon, Basingstoke, Hampshire 2001, pp. 77-78. Annemarie Weyl Carr has suggested another possible way of understanding this iconography. She views it in light of the Virgin’s veil as a metaphor for protection at the time. Carr suggests that the Metropolitan Madonna was a first step toward the ideas achieved in his London triptych of 1315, in which the Child grabs the veil and pulls it across his bare chest. In the latter image, she suggests the veil is meant to «cloak her child’s divinity and shroud his mortality», and that the thin fabric is «powerless to protect». This is certainly a convincing interpretation of the London triptych. However, as the Child in the Metropolitan Madonna does not pull the fabric toward himself, nor is he mostly nude and vulnerable as he is in the London work, I would suggest perhaps there is another possible interpretation for the gesture here. Perhaps, beyond the interpretation I suggest above, the gesture of the Child grabbing the veil may be a way to emphasize her protective abilities, which would further heighten the apotropaic quality of the painting. 44 See note 12. 45 See Anne Derbes’ discussion of this iconography in her 34 115 LYNLEY ANNE HERBERT book Picturing the Passion in Late Medieval Italy: Narrative Painting, Franciscan Ideologies, and the Levant, Cambridge 1996. 46 Triptych with Man of Sorrows, Mother of Sorrows, and John (image when closed depicts two Dominican friars), c. 1300. This work offers a perfect comparison, as Mary’s pose, gesture, glance, and use of her own veil to dab her eyes are nearly identical. It is in a private collection in the Netherlands, and I was unable to secure the rights to reproduce the image here. It has recently been published in A. DERBES, A. NEFF, Italy, the Mendicant Orders, and the Byzantine Sphere in Byzantium: Faith and Power (1261–1557), ed. H. C. Evans, New York 2004, pp. 448461: 457, fig. 14.14. For a full discussion of the triptych, see H.W. VAN OS, The Discovery of an Early Man of Sorrows on a Dominican Triptych, «Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes», XLI (1978), pp. 65-75. 47 M. BACCI, The Legacy of the Hodegetria: holy icons and legends between East and West, in Images of the Mother of God: Perceptions of the Theotokos in Byzantium, ed. M. Vassilaki, Aldershot 2005, pp. 321-336: 325. 48 M. ALEXIOU, Ritual Lament in Greek Tradition, Cambridge 1974, pp. 68-69. The Virgin cries, «give way to me, men, that I may reach him who was fed on the milk of my breasts…». For further discussion of this and other Byzantine works that connect the Virgin’s early motherhood with the Passion, see also A. DERBES, Byzantine Art and the Dugento: Iconographic Sources of the Passion Scenes in Italian Painted Crosses, Ph.D. diss., University of Virginia 1980, pp. 209-210, 252, nn. 22-24; H. MAGUIRE, Art and Eloquence in Byzantium, Princeton 1981, pp. 91-108. 49 DERBES, Byzantine Art and the Dugento, p. 252, nn. 2224; CORRIE, Coppo di Marcovaldo’s Madonna del Bordone, pp. 43-65. 50 This diptych offers important parallels to the Metropolitan Madonna in several ways. It couples the two components Duccio blends together, and its small scale indicates that it was also intended for private devotional use (each panel measuring 32.4 by 22.8 cm, or about 13 by 9 inches). On both the Duccio and the Umbrian paintings, a decorative inner frame can be found within an engaged frame. Intriguingly, in both of these the inner frames only run along the top and the sides of the image, which, although not completely unique, appears to be an unusual design element in paintings from this period. 51 CORRIE, Coppo di Marcovaldo’s Madonna del Bordone, p. 58. 52 DERBES, Picturing the Passion, p. 28. 53 The unusual feature of the ‘parapet’ has in fact recently led to the suggestion that this painting could not be genuine. In July 2006, the attribution to Duccio and c. 1300 date of the painting was challenged by James Beck. Beck asserted that the Duccio painting must be a later forgery since the idea of a parapet creating a plane in front of the figures would have been anachronistic in Duccio’s time, and is «a characteristic of Renaissance, not Medieval pictures».See the article: D. ALBERGE, $50m ‘Masterpiece’ is Poor Forgery, Says Arts Professor, «The Times Online», July (2006), available: http://www.timesonline.co.uk/article/0,,11069-2257809,00.html. The possibility that this painting is a later forgery has been dismissed by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, as well as leading Duccio scholars such as Luciano Bellosi, who assert that the piece has been analyzed both stylistically and scientifically, 116 including pigment tests and X-rays, all of which revealed the painting to be «entirely consistent with others from the period». See this rebuttal in R. POGREBIN, Authenticity of a Duccio Masterpiece at the Met is Challenged, «New York Times», July 8 (2006), available: http://www.nytimes.com/ 2006/07/08/arts/design/08ducc.html. Beck’s point of departure, that of the problematic making the architectural motif in the Duccio painting a parapet and forerunner of the later motif by Bellini et al, however, perhaps has some validity. See the above discussion for an alternative view. 54 WHITE, Duccio, p. 62. 55 R. GOFFEN, Giovanni Bellini, New Haven 1989, p. 34. 56 SCHMIDT, Painted Piety, pp. 145-149; CHRISTIANSEN, Duccio, pp. 50-52. 57 CHRISTIANSEN, The Metropolitan’s Duccio, p. 46. Christiansen suggests the angling of the consoles this way may mean that the painting was meant to be viewed while kneeling. 58 Metropolitan Museum, Early Renaissance Masterpiece, p. 4; STUBBLEBINE, Duccio di Buoninsegna, p. 28; WHITE, Duccio, p. 62; Duccio alle origini della pittura senese, pp. 134-136. 59 V. SCHMIDT, The Lunette Shaped Panel and Some Characteristics of Panel Painting, in Italian panel painting of the Duecento and Trecento, ed. V. M. Schmidt, Washington D.C. 2002, pp. 83-101: 85. Schmidt says it was most likely «an overdoor or part of sepulchral monument». In ID., Painted Piety, p. 144, the author specifically compares this painting to the Duccio, and concludes the corbels do not have the same function in both works since the architecture in the Montepulciano work is intended to embed the painting in the wall. The Metropolitan Museum has however cited this painting as proof of the contemporary use of a parapet motif in Duccio’s sphere in POGREBIN, Authenticity of a Duccio Masterpiece, p. 2. 60 MAGINNIS, The World of the Early Sienese Painter, p. 109. Maginnis notes that «the size and variety of content, limited or extensive, were undoubtedly determined by the patron’s expenditure». 61 Il Museo di San Marco, ed. I. Favaretto, M. Da Villa Urbani, Venice 2003, p. 103. 62 Ibid. The saints are identified as Peter, Paul, Mark, Nicholas, the Magdalene, and Margaret. Along the top edge of the frame are archangels flanking a Christ Pantocrator, whose book reads «I am the light of the World». 63 Although we have official documentation for much of his life, there is a gap in the documents during the period of the Metropolitan Madonna’s creation, between 1295 and 1302. See Duccio di Buoninsegna: The Documents and Early Sources, ed. J.I. Satkowski, H.B.J. Maginnis, Athens, GA 2000, pp. 63-64. It has therefore been suggested by some scholars that Duccio traveled during this time, and their thoughts on where he went range from Rome, to Paris, and even to parts of the Byzantine world. STUBBLEBINE, Duccio di Buoninsegna, p. 4, suggests other regions of Italy, particularly Rome, and possibly Paris; WHITE, Duccio, p. 56, suggests it is possible he could have ventured into the Byzantine world, which could be achieved by simply going to the «Eastern shores of the Adriatic» which would have artistically been viewed as Byzantine outposts. He does not, however, see any evidence that Duccio did so. D. NORMAN, Duccio: the recovery of a reputation, in Siena, DUCCIO’S METROPOLITAN MADONNA: BETWEEN BYZANTIUM AND THE RENAISSANCE Florence, and Padua: Art, Society, and Religion 1280-1400, ed. D. Norman, New Haven 1995, pp. 49-71: 55-57. Norman believes he may have traveled to Cyprus, for she cites a mural there that may be the prototype on which Duccio based his Madonna of the Franciscans, painted between 1295 and 1300. 64 E.B. GARRISON, Note on the Survival of ThirteenthCentury Panel Paintings in Italy, «The Art Bulletin», LIV (1972), p. 140. Garrison points out the percentage of panel paintings lost from this period is incredibly high – possibly as much as 99%. 65 Ibid.; Venezia e Bisanzio (cat. della mostra, Venezia, Palazzo Ducale, 8 giugno-30 settembre 1974), ed. I. Furlan, G. Mariacher, Milan 1974, nr. 66. 66 SCHMIDT, Painted Piety, p. 143. 67 BELTING, Likeness and Presence, p. 203. 68 SCHMIDT, Painting and Individual Devotion, p. 31. 69 SCHMIDT, Painted Piety, p. 143. 70 NIKETAS CHONIATES, O City of Byzantium: Annals of Niketas Choniatïs, trans. H. I. Magoulias, Detroit 1984, pp. 209-210. In the Annals it states that in 1186, when John Branas’ army was about to attack Constantinople, the Emperor Isaakios Angelos called on the Virgin to protect the city. «He carried up to the top of the walls, as an impregnable fortress and an unassailable palisade, the icon of the Mother of God taken from the monastery of the Hodegoi where it had been assigned, and therefore called Hodegetria». 71 M.S. FRINTA, Searching for an Adriatic painting workshop with Byzantine Connection, «Zograf», XVIII (1987), pp. 12-20: 12, n. 6. An article that has recently been called to my attention and that makes this argument more fully is J.T. WOLLESEN, The Case of the Disappeared Stoclet Madonna, «Pantheon», LVI (1998), pp. 4-9. He does not appear to be aware of Frinta’s thought on this, and seems to have come up with a similar theory independently. Although he does argue that this image is intended to show the Hodegetria of Constantinople in situ, he does not appear to consider it to retain its icon status, but rather believes it to be a «variation of an official Madonna and Child configuration (…) in order to make it fit into a new and unprecedented context of the private pictorial and devotional realm of Western panel paintings». It is interesting to note that this idea put forth by both Frinta and Wollesen has not been mentioned by the Metropolitan Museum, nor does it appear to have had any impact on their, or anyone else’s, perceptions of the Metropolitan Madonna. 72 CHRISTIANSEN, The Metropolitan’s Duccio, p. 44. Christiansen briefly describes the border’s design and relates it to a few other borders used by Duccio in terms of how it helps date the painting, but he goes no further with his analysis of the design itself. He does, however, discuss it as original to the painting, and states that it is not a punched design but is «entirely hand-inscribed and of great elegance». 73 D.P. WALEY, Siena and the Sienese in the Thirteenth Century, Cambridge 1991, pp. 149-150. It was common for the Sienese of both genders to designate considerable parts of their wills to the aid of the Crusaders and their expeditions, especially in the last quarter of the 13th century. The brethren at S. Maria della Scala are even known to have included the Crusaders in their prayers. Therefore, there was considerable awareness of and interest in the Crusades in Siena by the time Duccio was creating the Metropolitan Madonna. It is not impossible that this painting was created for someone with this interest, or who was in some way involved in the Crusades. 74 D. MOURIKI, Thirteenth-century Icon Painting in Cyprus, Athens 1986, pp. 15-16. She points out that the specific combination of floral geometric patterns appears frequently in Syriac manuscripts. 75 Mother of God, no. 62. 76 I was unable to secure rights to publish this image, Perugia, Biblioteca Capitolare. Ms. 6, fol. 182v. See H. BUCHTHAL, Miniature Painting in the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, Oxford 1957. Reprint, London 1986, pl. 57a. 77 Mother of God, no. 62, p. 406. Athanasios Papageorgiou argues this in the catalog entry for the icon of the Mother of God Arakiotissa. 78 C. BARBER, Figure and likeness: on the limits of representation in Byzantine iconoclasm, Princeton 2002, p. 29. He explains that the «icon could be a copy of a miraculous image and still claim the same status as the original. Thus, the painted icon must be understood as both a depiction and a relic». See also G. VIKAN, Ruminations on Edible Icons: Originals and Copies in the Art of Byzantium, in Retaining the Original: Multiple Originals, Copies, and Reproductions, ed. K. Preciado, Washington 1989, pp. 47-59. 79 D. NORMAN, Painting in Late Medieval and Renaissance Siena, 1260-1555, New Haven 2003, p. 41. 80 The concept of the Virgin and Child being called on as a city’s protectors, and their image being invoked as a palladium against enemies has obvious roots in Constantinople, but it had also been adopted in other parts of the West. For instance, see F. PRADO-VILAR, The Gothic Anamorphic Gaze: Regarding the Worth of Others in Under the Influence: Questioning the Comparative in Medieval Castile, ed. C. Robinson and L. Rouhi, Leiden 2005, pp. 67-100: 79-81. Prado-Vilar relates that in the Cantigas de Santa Maria, created in Spain in the late 13th century for King Alfonso X, Mary was «presented as head and protector of an inclusive national identity». In Cantiga 292, the king says that when going into battle against the Moors, his father carried a statue of the Virgin with him, and whenever he conquered one of their cities, he put an image of the Virgin on the gate of the mosque. One of the illuminations shows Muslim and Christian soldiers marching together under the banner of the Virgin during the siege of Marrakesh. When they were victorious, they attributed much of their success to the Virgin’s help. 81 H.W. VAN OS, Sienese Altarpieces, 1215-1460: Form, content, function, trans. M. Hoyle, Groningen 1984, p. 11. 82 HEAL, ‘Civitas Virginis’?, p. 297. 83 WALEY, Siena and the Sienese, p. 116. 84 HEAL, ‘Civitas Virginis’?, p. 297. Heal has argued that Ventura’s story, and in general the intense dedication to the Virgin in the 13th century was a later fabrication read back into the city’s history. She believes it was the spirituality of the mendicants that stimulated the marian cult, and that the commune worked to propagate the concept of the Virgin as protectress of Siena only by the early 14th century. She suggests that earlier art and events were reinterpreted to build up the cult which was firmly in place by the time of the unveiling of Duccio’s Maestà. If we accept her 117 LYNLEY ANNE HERBERT interpretation, the mechanisms of propaganda would still have been well underway by the time Duccio was painting the Metropolitan Madonna in 1300, since by 1302 the commune was paying him for a Maestà panel for the Nine (Siena’s leaders), and in 1308 he was given a huge commission to paint the city’s new monumental Maestà altarpiece, the ultimate statement of dedication to the Virgin by the city of Siena. For these commission records see SATKOWSKI, MAGINNIS, Duccio di Buoninsegna: The Documents, pp. 66, 69-71. 85 R. CORRIE, The Political Meaning of Coppo di Marcovaldo’s Madonna and Child in Siena, «Gesta», XXIX (1990), 1, pp. 61-75: 62. Although Coppo was a Florentine, she argues that he was imprisoned after the battle and this painting was his payment for his freedom. 86 BELTING, Likeness and Presence, p. 387. 87 Perhaps it is no coincidence that in 1261, the same year that Coppo painted his Madonna for Siena, the power of the Hodegetria was reinstated in Constantinople. This timing may have been persuasive in the Sienese choice to emulate that image. Rebecca Corrie, in Coppo di Marcovaldo’s Madonna del Bordone, p. 58, believes that the protective power of the Byzantine Virgin type would have been recognized by the Sienese. 88 BACCI, The Legacy of the Hodegetria, p. 323. 89 Ibid., pp. 324-327. An example of this is found in the monastery of S. Maria del Patir in Calabria where a careful copy of the Hodegetria was known as the Neodigitria or «New Hodegetria» by 1111. 90 CORRIE, The Political Meaning, p. 68. 91 Ibid., n.79. 92 W.M. BOWSKY, The Finance of the Commune of Siena, 1287-1355, Oxford 1970, p. 2.; CORRIE, The Political Meaning, n.79. She notes this connection as well. 93 B.V. PENTCHEVA, The ‘activated’ icon: the Hodegetria procession and Mary’s Eisodos in Images of the Mother of God, pp. 195-207: 196. Her discussion includes two imperial seals from Constantinople – one from the 7th century and one from the 11th. Although they change somewhat over time, this demonstrates a long tradition of the Madonna and Child on the Byzantine imperial seal. 94 CARR, Threads of Authority, p. 77. 95 F. RATTÉ, Architectural Invitations: Images of City Gates in Medieval Italian Painting, «Gesta», XXXVIII (1999), pp. 142-153: 143; J. GARDNER, An Introduction to the Iconography of the Medieval Italian City Gate, «Dumbarton Oaks Papers» (Studies on Art and Archeology in Honor of Ernst Kitzinger on His Seventy-Fifth Birthday), XLI (1987), pp. 199-213: 212. 96 J. HOOK, Siena, a City and its History, London 1979, p. 132; RATTÉ, Architectural Invitations, pp. 142-143; CORRIE, Coppo di Marcovaldo’s Madonna del Bordone, p. 57. Corrie agrees that images on the gates would have «acknowledged and perhaps assured her protection»; STUBBLEBINE, Duccio di Buoninsegna, p. 122. He sees these images of the Virgin as less of a protective force in the Byzantine sense, and more as part of a system of signs, «signs in the popular use of the term and signs as emblems of ideas and means of propaganda. Images of the Virgin on the city gates, in the cathedral, on the Ospedale di Santa Maria della Scala, or in the Palazzo Publico told visitors of the city’s dedication 118 and its special devotions». 97 MAGINNIS, The World of the Early Sienese Painter, p. 132. The four gates identified as having images of the Virgin are the Porta Camollia (known through commission records), the Porta Romana (known only through an eyewitness account), the Porta Salaia (known through a commission for a roof over it), and the Porta San Viene (known from a commission - this was actually a panel painting). I should note that even in light of such overt declarations of devotion, Hayden Maginnis expresses his doubts about the spiritual character of Sienese art, and of the Sienese themselves; GARDNER, An Introduction, p. 212. 98 MAGINNIS, The World of the Early Sienese Painter, p. 131. The two painters are Ciecco and Nuccio, and the carpenter is a man named Chello. Maginnis assumes it is a «roof projecting over the image to shield it, at least partially, from the weather». The archive he cites is ASS, Biccherna 122, fol. 201v. 99 Ibid. I would suggest that the faithful repainting of the Virgin on the gate over this stretch of time, by lesser artists and not by the city’s famous painters, might support the concept of a functional, protective purpose for these images rather than a strictly artistic one. 100 GARDNER, An Introduction, p. 212. 101 BELTING, Likeness and Presence, p. 75. 102 For an excellent discussion of when and how the Hodegetria came to be viewed as a Saint Luke painting, see M. BACCI, With the Paintbrush of the Evangelist Luke, in Mother of God, pp. 79-89. According to Bacci, the Hodegetria icon, or the icon that belonged to the Hodegoi monastery of Constantinople, was probably not initially believed to be by Saint Luke, but was labeled as a Saint Luke icon well after it was painted. He believes it probably gained this reputation because the Hodegoi monastery had connections with Antioch, Luke’s birthplace, and because of the miracles it performed. 103 I should note that I have looked at the gates of Siena to see if there is any correlation between the built structure and Duccio’s corbels. While there appears to be some similar corbelling very high on the walls on some of the gates, such as can be seen near the top of the Porta Romana’s antiporta, it does not correspond to where the image would likely have been placed on the gate. Presumably the image would have adorned the front of the main gate, where today a small roof protrudes to provide shelter. There is, however, a small ledge along the bottom of that niche. It is possible there was such a ledge beneath the painting in Duccio’s time as well, and perhaps it looked much like the one he employs. I would still argue, however, that Duccio was most likely using a common artistic convention when he painted his corbels, and was probably not concerned with a precise rendering of the built environment, since that was not yet common practice. PHOTO CREDITS 2, 3, 4, 7, 9, 10, 13 (Art Resource) 1, 6 (Art Stor’s Images for Academic Publishing) 5 (London, The Royal Collectionnof Her Majesty the Queen) 8 (Montepulciano, Museo civico) 11 (Venezia, San Marco) 12 (London, British Museum) DUCCIO’S METROPOLITAN MADONNA: BETWEEN BYZANTIUM AND THE RENAISSANCE LA MADONNA DI DUCCIO DEL METROPOLITAN: TRA BISANZIO E IL RINASCIMENTO Lynley Anne Herbert Nell’autunno del 2004 il Metropolitan Museum of Art di New York ha acquistato una piccola tavola dipinta da Duccio di Buoninsegna per 45 milioni di dollari. Una spesa di tale entità è stata giustificata esaltando Duccio, e in particolare questa tavola, come una delle prime espressioni del Rinascimento. Il Museo ha affermato che l’opera mostra una chiara e consapevole rottura rispetto alle raffigurazioni rigide e schematizzate, considerate caratteristiche delle tradizioni occidentale e bizantina. Le basi di tale affermazione risiedono sia nella nuova interazione, intensamente umana e naturalistica, creata da Duccio tra Maria e Cristo, sia nella presenza di un insolito elemento architettonico, definito parapetto, che è interpretato come il precursore di un motivo utilizzato da Giovanni Bellini e da altri artisti del Quattrocento. Questo contributo esplora nuovi modi di vedere la Madonna del Metropolitan di Duccio – non guardando all’indietro, a partire dal Rinascimento, ma in avanti, da una prospettiva medievale e bizantina. Gli elementi umani utilizzati da Duccio – considerati una novità – potrebbero effettivamente essere una sintesi creativa di citazioni ed evocazioni delle icone orientali. Considerato alla luce delle ricerche di Hans Belting sulla trasmissione delle icone, tali citazioni orientali potrebbero indicare l’intenzione di infondere il potere spirituale delle icone in questo dipinto. Il contributo suggerisce, inoltre, che la Madonna del Metropolitan è stata progettata per evocare specifiche tradizioni all’interno del culto mariano nella città natale di Duccio, Siena. Molti indizi, infine, inducono a ritenere che nella Madonna del Metropolitan Duccio abbia fatto riferimento e abbia ricreato sia tipi bizantini consolidati, sia opere civiche senesi, trasformando abilmente il loro potere e il loro significato allo scopo di farne un’immagine devozionale privata. 119