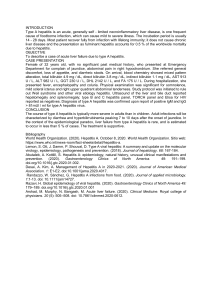

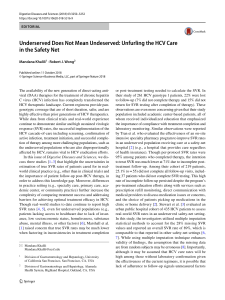

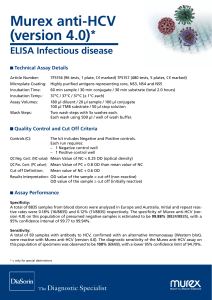

zyxw zyxw zyxwvutsrqponm zyx Copyright 0 Munkszuurd 1996 Liver 1996: 16: 331-334 Printed in Denmark . AN rights reserved LIVER ISSN 0106-9543 A prospective study of hepatitis C virus infection after needlestick accidents Arai Y, Noda K, Enomoto N, Arai K, Yamada Y, Suzuki K, Yoshihara H. A prospective study of hepatitis C virus infection after needlestick accidents. Liver 1996: 16: 331-334. 0 Munksgaard, 1996 I Abstract: There have been few prospective studies of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection after needlestick accidents in hospital employees. In the present study, the prevalence and features of HCV infection after needlestick accidents were evaluated prospectively measuring serum HCV-RNA. Subjects were 56 employees who had HCV needlestick accidents. To monitor the development of hepatitis, the serum ALT levels and HCVrelated seromarkers, such as first generation anti-HCV (RIA), second generation anti-HCV (PHA) and HCV-RNA (RT-PCR) were measured every month for at least 12 months after the accidents. Three of 56 (5.4%) recipients developed HCV infection. HCV-RNA was detected in all three recipients within 4 months after the exposure, and second-generation HCV antibody was detected in two of three recipients. The detection of HCV-RNA was earlier than that of HCV antibody. Two of three HCVinfected recipients developed type C acute hepatitis and one of two received interferon therapy; however, the other case received no medication. The detection of HCV-related seromarkers and the elevation of ALT levels were transient in these three recipients; thus, none developed chronic hepatitis. In conclusion, HCV infection developed in 5.4% of recipients within 4 months after HCV accidents. All of these HCV-infected recipients showed fair prognosis. HCV-RNA was a beneficial parameter for early detection of HCV infection. Vumi Arai, Katsuhisa Noda, Norihiro Enomoto, Keiichi Arai, Vukinori Vamada, Kunio Suzuki and Harumasa Voshihara Department of Gastroenterology, Osaka Rosai Hospital, Osaka, Japan zyxwvutsr Transmission of viral hepatitis via blood or blood products is a problem for health care workers. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is now controllable by both passive and active immunization (1-2). There have been a few reports concerning transmission of non-A, non-B (NANB) hepatitis infection in hospital employees through accidental exposure to patients’ blood (3-14). To our knowledge, there has been only one prospective study using assays for HCVRNA and antibodies to hepatitis C virus (HCV) which suggested that the risk of transmission of HCV is not so high as that of hepatitis B after needlestick injury (13). However, the prevalence and features of HCV infection after needlestick accidents have not been well-established. Therefore, in the present study, we evaluated prospectively the prevalence and features of HCV infection after needlestick accidents by measuring serum HCV-RNA chronologically. Key words: HCV-antibody - HCV-RNA - hepatitis C virus - interferon therapy - needlestick’ accidents Harumasa Yoshihara, M.D., Department of Gastroenterology, Osaka Rosai Hospital, 1179-3 Nagasone-cho, Sakai-city, Osaka 591, Japan Received 29 May 1995, accepted for publication 4 June 1996 Material and methods Patients The accidental exposure of a hospital employee to a patient’s blood through medical procedures was defined as a “needlestick accident”, such as percutaneous injury with noticeable bleeding by medical instruments contaminated with a patient’s blood, and splash of a patient’s blood into the eye. All needlestick accidents were reported to the Hepatitis Prevention Committee in our hospital by the injured employees. Subjects were 56 employees who had HCV needlestick accidents from January 1991 to August 1993 in our hospital. Measurements of liver function test and hepatitis virus seromarkers We measured second-generation anti-HCV (HCV 2nd) by passive hemagglutination (PHA, Abbott 331 Arai et al. zyxwvutsrq zyxwvu Laboratories) (15) and HBs antigen (HBsAg) by commercially available enzyme linked immunosorbent assay(EL1SA tests, Abbott Laboratories) in all donors routinely on admission before the accident. To monitor the development of hepatitis after needlestick accidents in recipients, the serum levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT; normal range, 0-30 IUA) as well as HCV-related seromarkers were measured every month for at least 12 months (length of follow-up, 18.926.6 months). As HBV-related seromarkers, HBsAg and HBs antibody (HBsAb) were also measured just after the accident. As HCV-related seromarkers, we measured first-generation anti-HCV (HCV 1st) by radioimmunoassay (RIA, Ortho kit), second-generation anti-HCV (HCV 2nd) by PHA (Abbott Laboratories), and HCV genomic RNA (HCVRNA) detected by a reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay using primers from the highly conserved 5' non-coding region (16) in all HCV-needlestick recipients. The infection of HCV was diagnosed by the positiveness of serum HCV-RNA in association with the positiveness of HCV antibody or an increase in serum ALT level. Additionally, in one case of acute hepatitis after the accident, serum HCVRNA levels and genotype were also analyzed by competitive RT-PCR (17) and RT-PCR (18), respectively. All recipients were confirmed to be negative for HBsAg, HCV Ist, HCV 2nd and HCV-RNA just after the needlestick accidents. All donors were confirmed to be negative for HBsAg and positive for HCV 2nd. Results (-) HCV2nd * HCV-RNA 7 (+) (-) zyx zyxwvut zy OJ '91' 5 6 " \\-\I- " ' '92" " 9 10 11 12 1 2 3 4 5 " 7 8 'I4 month zyxwvuts zyxwvut zyxwvut As to the mode of exposure of health care workers to patient's blood, needlesticks were observed in 49 (87.5%), which was the most frequent accident in all 56 cases. The other modes of accidents were cuts with sharp objects in 4 (7.1%), splash into eye in 2 (3.6%) and blood contamination of a wound in 1 (1.8%). HCV infection developed in 3 of 56 (5.4%) recipients after anti-HCV positive needlestick accidents. All three donors were negative for HBsAg and positive for HCV 2nd, associated with chronic liver disease. Recipients who turned positive for anti-HCV lst, anti-HCV 2nd and HCVRNA were 1 of 56 (1.8%), 2 of 56 (3.6%) and 3 of 56 (5.4%), respectively. None of the three recipients had a history of hepatitis and drug abuse or heavy drinking of alcohol. These three recipients had normal liver function test and negative HBV- and HCV-related seromarkers (anti-HCV 1st, antiHCV 2nd, HCV-RNA) at the time of needlestick accidents and were negative for HBV-, EpsteinBarr virus- and cytomegalo virus-related serum 332 HCVlst Fig. 1. A clinical course following needlestick accident in case 1 . The recipient was a 21-year-old nurse. A11 HCV related markers were measured every month. The normal range of ALT level and negative serum HCV-related markers persisted for more than one year after normalization of ALT. 3 \ 2 30. 20 E 2 8 04 '92 ' 1112 "93 1 ' 2 ' ' 3 4 ' 5 7 '94' ' ' ' 6 8 9 2 month Fig. 2. A clinical course following needlestick accident in case 2. The recipient was a 29-year-old nurse. All HCV-related markers were measured every month. markers at the time of developing hepatitis. Of the three HCV-infected recipients, two cases showed no elevation or slight elevation of serum ALT level (below 60 IUA) during their clinical course after the accidents and received no medications (Figs. 1 and 2). One case showed typical acute hepatitis, associated with an elevation of serum ALT level up to 1375 IUA, and positiveness of anti-HCV lst, anti-HCV 2nd and HCV-RNA, and received interferon (IFN) therapy. In the donor, serum HCVRNA level was lo6 copy/ml and genotype was type 11, while, in the recipient, the peak level of HCVRNA was lo8 copy/ml and genotype was type I1 (Fig. 3). In the three HCV-infected recipients, the detection of HCV-RNA was earlier than that of HCV antibody or abnormal serum ALT levels. In addition, one HCV-infected recipient showed positive HCV-RNA in the absence of any positive- zy zyxwvutsrqpo HCV infection after needlestick accidents zyxwvutsrqpon zyxwvutsrq 1.4 2.5 5.9 10 - +‘ HCV2nd + + - HCV 1st 9.5 2.3 1.5 ’+ ’+ 4 HCV-RNA1 mi) (COPY + + -‘ b r <lo4 108 <1$* Liver 5 1000 U zyxwvuts zyxwvutsrqponm f 500j w zee-infection units for HBeAg-positive sera (21). Thus, the most probable explanation for the low rate of infection after anti-HCV-positive needlestick accidents is that the amount of contaminated blood is very little and that the titer of HCV in human sera is orders of magnitude lower than the titer of HBV in HBeAg-positive human sera. In the present study, HCV-RNA was detected within 4 months after the exposure. HCV-RNA was detected earlier than the other HCV-related seromarkers or an elevation of serum ALT level, indicating that HCV-RNA is a beneficial parameter for early detection of HCV infection. Kato et al. (22) also reported that, in acute non-A, non-B hepatitis, HCV-RNA was detected 9 2 1 1 weeks before the detection of anti-Cl00-3. Omata et al. (23) reported the effectiveness of IFN therapy for acute NANB hepatitis, and for the prevention of chronic hepatitis. In the present study, one case was administered IFN to avoid developing chronic hepatitis. However, there is also a possibility that IFN therapy affected, to a minimal extent, the natural course of acute hepatitis C, since her serum ALT level returned to the normal level before IFN therapy. The number of reports is extremely limited as to the long-term prognosis of acute hepatitis after HCV-needlestick accidents. Sodeyama et al. (13) reported two recipients of HCV-needlestick accidents who developed acute hepatitis, followed by chronic hepatitis in the presence of serum HCV-RNA. By contrast, our study showed fair prognosis of three HCV-infected recipients, without developing chronic hepatitis, giving an evident difference from Sodeyama’s report. The type C post-transfusion hepatitis is well known to be associated with following chronic hepatitis in 40 to 50% of cases (24). The present finding cannot be evidence for the different prognosis between type C post-transfusion hepatitis and HCV-needlestick accidents since the number of HCV-infected recipients was too small. Thus, in order to clarify the long-term prognosis of HCVinfected recipients after needlestick accidents, further studies are required. o ( :: ‘94 3 month Fig. 3. A clinical course following needlestick accident in case 3. The recipient was a 22-yedr-old nurse. Each number on the arrow of anti-HCV 1st indicates the titer. The interferon (IFN) was administered daily for 2 weeks, thereafter intermittently for 10 weeks. The histology of liver biopsy was compatible with that of recovery stage in acute hepatitis. ’93 4 8 10 12 HCV antibodies. The elevation of serum ALT levels and the detection of HCV-seromarkers were transient resulting in a normalization of ALT levels and disappearance of HCV-RNA during the observation period. Thus, all these HCV-infected recipients showed fair prognosis. Discussion There have been a few retrospective studies concerning transmission of NANB hepatitis (3-14) or type C hepatitis (9) in hospital employees through accidental exposure to patients’ blood. However, to our knowledge, there has been only one prospective study concerning the risk of transmission of HCV after needlestick injury; i.e., Sodeyama et al. (13) reported that acute hepatitis C developed in 2 of 62 (3.20/0)recipients when donors were positive for anti-C100-3, and in 2 of 88 (2.3%) when donors were positive for anti-HCV 2nd. However, in his study, HCV-transmission was not confirmed by the detection of HCV-RNA in all recipients. The infection rate (5.4%) of HCV needlestick accidents in the present study seems to be a little bit higher than Sodeyama’s report (2-3%), which might be attributed to the measurement of HCVRNA in all recipients of our study. The rate of HCV infection after HCV-needlestick accidents is low compared with the rate of 67% found in HBeAg-positive needlestick accidents (19). The infectivity titer of human non-A, non-B hepatitis sera is generally less than 1O2 chimpanzee-infection units, as shown in chimpanzee transmission studies (20), which is extremely lower than lo8 chimpan- References zyxw 1. SEEFFL B, WRIGHTE C, ZIMMERMAN H J, et al. Type B hepatitis after needlestick exposure: prevention with hepatitis B immune globulin: final report of the Veterans Administration cooperative study. Ann Intern Med 1978: 88: 285-293. . 2. SEEFTL B, HOOFNAGLE J H. Immunoprophylaxis of viral hepatitis. Gastroenterol 1979: 77: 161-182. 3. KIYOSAWA K, GIBOG, SODEYAMA T, et al. Possible infectious causes in 651 patients with acute viral hepatitis during a 10-year period (1976-1985). Liver 1987: 7: 165-168. 4. ALTERM J, GERETYR J, SMALLWOOD L A, et al. Sporadic 333 zyxwvutsrq zyxwvutsrqp zyxwvutsrqpo zyxwvutsr Arai et al. non-A, non-B hepatitis: frequency and epidemiology in an urban US population. J Infect Dis 1982: 145:886-893. 5. GERBERDING J L.Current epidemiologic evidence and case reports of occupationally acquired HIV and other blood borne disease. Infect Control Hosp Epidemioll990:11: 558- 560. 6.AHTONEJ, FRANCIS D, BRADLEY D, MAYNARD J. Non-A, non-B hepatitis in a nurse after percutaneous needle exposure. Lancet 1980: 1: 1142. W, PETERSON E, TAYLOR J W. Non-A, non-B hepa7. HERRON titis infection transmitted via a needle. M M W R 1978: 28: 157-158. 8. MAYO-SMJTH M F. Type non-A, non-B and type B hepatitis transmitted by a single needlestick. A m J Infect Control 1987: 15: 266-261. 9. VAGLIA A, NICOLIN R, PUROV, IPPOLITO G, BETTJNI C, DELALLA H. Needlestick hepatitis C virus seroconversion in a surgeon. Lancet 1990:36: 1315-1316. U. ROCGENDORF M, CHOLMAKOW K, WJSE 10. SCHLJPKOTER A, DEINHARDT F. Transmission of hepatitis C virus (HCV) from a haemodialysis patient to a medical staff member. Scrrnd J Infect Dis 1990: 22:757-758. 11. KIYOSAWA K, SODEYAMA T, TANAKA E, et al. Hepatitis C in hospital employees with needlestick injuries. Ann Intern Med 1991: 115: 367-369. 12. CARIANI E,ZONARO A, PRJMID, et al. Detection of HCVi RNA and antibodies to HCV after needlestick injury. Lancet 1991:337: 850. 13.SODEYAMA T, KIYOSAWA K, URUSHIHARA A, et al. Detection of hepatitis C virus markers and hepatitis C virus genomicRNA after needlestick accidents. Arch Intern Med 1993: 153: 1565-1572. 14. FUKUI T, NODAH, HINAMIF, et al. Blood contamination for medical staff and positive rate of HCV antibody in inpatients. Jpn J Traumatol Occup Med 1992:40:603-607. 15. OSADAK, SAMESHIMA Y, FUJIIH, SHIMIZU M, WATANABE J, NISHIOKA K. Effect of donor blood screening for antiHCV antibody by the second-generation passive hemagglutination test on the incidence of post-transfusion hepatitis. In: Nishioka, ed. Viral hepatitis and liver disease. Hong Kong: Springer-Verlag Tokyo Publishing, 1994: 562-564. 16. ULRICHP P, ROMEOJ M, LANEP K, KELLYI, DANIEL W, VYASG N. Detection, semiquantitation, and genetic vari- ation in hepatitis C virus sequence amplified from the plasma of blood donors with elevated alanine aminotransferase. J Clin Invest 1990:86: 1609-1614. 17. GILLILAND G, PERRIN S, BLANCHARD K, BUNNH F. Analysis of cytokine mRNA and DNA: detection and quantitation by competitive polymerase chain reaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990:87: 2725-2729. 18. OKAMOTO H, SUGIYAMA Y, OKADA S, et al. Typing hepatitis C virus by polymerase chain reaction with type-specific primers: application to clinical surveys and tracing infectious sources. J Gen Virol 1992: 73: 673-679. 19.US. National Heart and Lung Institute Collaborative Study Group and Phoenix Laboratories Division, Bureau of Epidemiology, Center for Disease Control. Relation of e antigen to infectivity of HBsAg-positive inoculations among medical personnel. Lancet 1976:2: 492. 20. YOSHIZAWA H. ITOH Y, IWASAKI S, et al. Non-A, non-B (type 1) hepatitis agent capable of inducing tubular structures in the hepatocyte cytoplasm of chimpanzees: inactivation by formalin and heat. Gastroenterol 1982: 82: 502- zyxwvutsrq zyxwvutsrq 334 506. 21. SHIKATA T, KARASAWA T, ABEK, et al. Hepatitis B e antigen and infectivity of hepatitis B virus. J Iffect Dis 1977: 136: 571-576. 22. KATON,YOKOSUKA 0, HOSODA K, ITOY, OHTAM, OMATA M. Detection of hepatitis C virus in acute non-A, non-B hepatitis as an early diagnostic tool. Biochem Siophys Res Comm 1993: 192:800-807. 23. OMATAM, YOKOSUKA 0, TAKANO S, et al. Resolution of acute hepatitis C after therapy with natural beta interferon. Lancet 1991:338: 914-915. 24. KORETZR L, STONE0,GITNJCK G L. The long-term course of non-A, non-B post-transfusion hepatitis. Gastroenterol 1980:79:893-898.