Anita Woolfolk Wayne Kolter Hoy - Instructional Leadership A Research-Based Guide to Learning in Schools-Pearson (2012)

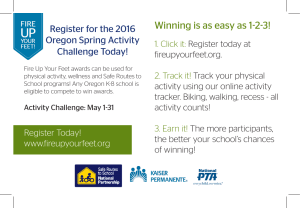

Anuncio