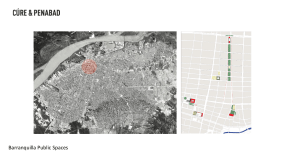

SHILPA PHADKE, SAMEERA KHAN AND SHILPA RANADE Why Loiter? Women and Risk on Mumbai Streets PENGUIN BOOKS Contents About the Authors Prologue CITY LIMITS 1. Why Mumbai? 2. The Unbelongers 3. Good Little Women 4. Lines of Control 5. Consuming Femininity 6. Narrating Danger 7. Courting Risk EVERYDAY SPACES 8. Public Space 9. Commuting 10. Peeing 11. Playing 12. Designed City IN SEARCH OF PLEASURE 13. Who’s Having Fun? 14. Can Girls Really Have Fun? 15. Do Muslim Girls Have less Fun? 16. Do Rich Girls Have more Fun? 17. How Do Slum Girls Have Fun? 18. When Do Working Girls Have Fun? 19. May Night Girls Have Fun? 20. Can Girls Buy Fun? 21. Can Different Girls Think of Fun? 22. How Do only Girls Have Fun? 23. Do Old Girls Have Fun? 24. Where Do Girls Have Fun? 25. Can Good Girls Have Fun? IMAGINING UTOPIAS 26. Why Loiter? Notes References Acknowledgements Copyright Page ABOUT THE AUTHORS Shilpa Phadke is a sociologist. She is Assistant Professor at the Centre for Media and Cultural Studies at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai. She has been educated at St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai, SNDT University, Mumbai and the University of Cambridge, UK. She conceived and led the Gender and Space project at PUKAR. Her areas of concern include pedagogy; middle-class sexuality and the new spaces of consumption; feminist politics among young women; and urban transformations. She has published widely in newspapers and magazines and in academic journals and books. She loves the chaotic city of Mumbai and fantasizes that it will one day have a very large park. Sameera Khan is a Mumbai-based journalist, writer, and researcher. A former assistant editor at the Times of India, she currently teaches journalism at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences and is a research associate with PUKAR, an urban research collective, where she worked on the Gender and Space project. An active founder member of the Network of Women in Media, India, she has contributed essays to several anthologies including Bombay, Meri Jaan: Writings on Mumbai and Missing: Half the Story, Journalism as if Gender Matters. She has a BA in history and Anthropology from St. Xavier’s College, University of Bombay, a diploma in mass communications from Sophia Polytechnic, and an MS in journalism from Columbia University, New York. Shilpa Ranade is a practising architect and researcher. She trained in architecture from CEPT, Ahmedabad and has an MA in Comparative Cultural and Literary Studies, University of Arizona, Tucson: her thesis examined the trope of motherhood in late twentieth century Hindu nationalism. She has been associate editor of the South Asian volume in the series ‘World Architecture 1900– 2000: A Critical Mosaic’ and has also published articles in various architectural magazines. Shilpa is a founding partner of the design collaborative DCOOP where her portfolio includes interior, architecture, landscape and urban design projects. Advance praise for Why Loiter? This short, elegantly written book questions the myth that Mumbai is a paradise for women in public. The authors show that women of different class and cultural backgrounds in Mumbai operate under serious social, political and infrastructural constraints, and that the right to loiter is no more and no less than the right to everyday life in the global city. This book will appeal to social scientists, urbanists, gender scholars and, more generally, to all those who want to take fun more seriously. —Arjun Appadurai, Goddard Professor of Media, Culture and Communication, New York University To ask the question ‘Why loiter?’ is to place the issue of gender and space within the right perspective. Because it goes beyond safety and protection; it asserts women’s right to public space, to do as they wish, instead of using it as a necessity for transiting from one point to another. This is the best part of this eminently readable, accessible and informative book—it meshes theory with experience, it is written in a lively style (not always evident in academic writing) and it recounts real-life experiences that will resonate with every woman, regardless of her age. —Kalpana Sharma, independent journalist, columnist, and author of Rediscovering Dharavi: Stories from Asia’s Largest Slum Prologue Imagine an Indian city with street corners full of women: chatting, laughing, breast-feeding, exchanging corporate notes or planning protest meetings. Imagine footpaths spilling over with old and young women watching the world go by as they sip tea, and discuss love, cricket and the latest blockbuster. Imagine women in saris, jeans, salwars and skirts sitting at the nukkad reflecting on world politics and dissecting the rising sensex. If you can imagine this, you’re imagining a radically different city. It’s different because women don’t loiter. Men hanging out are a familiar sight in the city. A man may stop for a cigarette at a paanwalla or lounge on a park bench. He may stop to stare at the sea or drink cutting chai at a tea stall. He might even wander the streets late into the night. Women may not. We argue that there’s an unspoken assumption that a loitering woman is up to no good. She is either mad or bad or dangerous to society. Of course, no one actually says this out loud. But every little girl is brought up to know that she must walk a straight line between home and school, home and office, home and her friend or relative’s home, from one ‘sheltered’ space to another. This book maintains that all of us, whether we’re women or men, regardless of our differences, have the right to loiter. When society wants to keep a woman safe, it never chooses to make public spaces safe for her. Instead, it seeks to lock her up at home or at school or college or in the home of a friend. In this book, we explicitly foreground the middle-class woman because although public discussions of safety might appear to be about all women, they tend to focus implicitly only on middle-class women. In the urban Indian context, this middle-class woman is further assumed to be a young, able-bodied, Hindu, upper-caste, heterosexual, married or marriageable woman. A man with her set of identities would have open, legitimate and unquestioned access to public space. The middle-class woman is then apparently privileged in every way other than gender. Focusing on this woman then allows us to unravel the implicit assumptions of gender, class, caste, community and sexuality that underlie popular notions of safety. Though the work is based in Mumbai, we hope the ideas and debates in this book will find resonance with the experiences of women in other cities in India and the world, especially those that are re-envisioning themselves as global cities. We also engage with the common myth that feminism is passé in the twenty-first century, and show just why and how relevant feminist politics is to re-imagining a vibrant and inclusive concept of citizenship in contemporary India. We draw on the findings of a three-year-long research project, the Gender and Space project that focused on women and public space in Mumbai to demonstrate beyond reasonable doubt that despite the apparent visibility of women, even in urban India, women do not share equal access to public space with men. Women in Mumbai have, at best, conditional access to public space. Turning the safety argument on its head, we now propose that what women need in order to maximize their access to public space as citizens is not greater surveillance or protectionism (however well meaning), but the right to take risks. For we believe that it is only by claiming the right to risk, that women can truly claim citizenship. To do this we need to redefine our understanding of violence in relation to public space—to see not sexual assault, but the denial of access to public space as the worst possible outcome for women. Instead of safety, what women would then seek is the right to take risks, for it is only by claiming the right to risk that we can truly claim citizenship. The early ideas for this project were born in 1997, while one of us, Shilpa Phadke, was travelling through Agra, Gwalior, Jhansi, Orccha and Datia in North India with a friend. We reproduce some edited notes from her travel diary: As two women travellers, or ‘laydeej’, we were well aware of the need to plan the minutest details. Our hotels and guesthouses were booked in advance. The train tickets were reserved mindful of delays. We could not leave before it was light or arrive after dark. Our clothes were chosen to be as little out-of-place as possible. As urban bal-kati auratein (short-haired women) we could not hope to blend in completely but nor did we want to draw undue attention. Interestingly, it was our very difference that sometimes kept us relatively safe—for despite being Indian women, we were clearly outsiders, not subject to the same rules as the women who lived there. Nonetheless this did not mean we were not harassed. In our guesthouse in Agra, we put a chair under our door handle as we heard repeated knocks on the door well after midnight. At the Gwalior fort we finally succumbed and hired a guide (a man, of course—are there any other kind?), his presence ‘protecting’ us from many offers of guidance and other things. At the palace-fort in Orchha we held our breath when a group of men loudly talking to each other and verbally harassing us went by without doing more. As they passed us, both of us saw vivid images of gang rape in our minds. That holiday passed off without anything worse than verbal harassment and strange and leering looks. Despite the pleasure we found in our travels, there was a sense that as women we did not have access to the full range of travelling pleasures. In Mumbai I find myself back on my local train route thinking about being back in familiar terrain. Our careful strategizing in the north brings home to me sharply how much I actually strategize even in my own city in order to be able to access public space. Discussing this with other women, I realize that almost without being aware of it, every woman reflects deeply about how to access public space. Our safety is something that at a visceral level none of us take for granted but strangely enough, this need to plot, plan and strategize has come to assume the proportions of a taken-forgranted life-world for all of us. As I ask questions of them and myself, this sense of stoic taken-for-grantedness crumbles, producing angry and humiliated stories of harassment. Using these stories as the starting point to query women’s access to public space, Shilpa Phadke began writing a preliminary project proposal and discussing it with colleagues at the urban research collective, Partners for Urban Knowledge Action and Research (PUKAR) in 2001. Sameera Khan and later, Shilpa Ranade, became first important interlocutors and then integral partners to the research project. Our multiple and cross-disciplinary dialogues sustained and enriched the project as it grew into something larger and more exciting than any one of us could have done on her own. A generous grant from the Indo-Dutch Programme on Alternatives in Development (IDPAD) allowed us to conduct extensive research on questions of gender and public space. This book draws on this research conducted in Mumbai from September 2003 to September 2006. During this period, we studied fourteen different areas in the city across geographical location, class and religious affiliations, and usage. Segments of four of these localities were also ‘architecturally’ mapped into drawings that demonstrated women’s movements in public space. We also conducted ethnographic observations at five suburban railway stations, four public parks, three private shopping malls and four coffee shops. The methodology of the Gender and Space project was multipronged. The conventional techniques included locality studies, ethnography and mapping, which are accepted methods from the fields of social sciences and urban planning. These provided us with extensive and intensive information about the city through interviews, focus group discussions, participant observation, architecturalmapping, city planning data, secondary sources in the media and scholarly literature on the city. Our aim was not only to collect data for our research, but also to engage in advocacy and to initiate a more public debate in the city. Therefore, we deliberately chose to also engage with nonconventional research techniques such as video and audio documentaries and photography to complement our conventional methodologies.1 The project worked with Central Railway officials to assess thirty-five local train stations for lighting levels. In addition, we conducted three long courses and numerous short workshops with undergraduate students of sociology, history, architecture, applied arts and mass communication, and the discussions in these pedagogic contexts are also reflected in our analysis. We also convened three open round-table discussions on relevant themes, organized a full-day academic seminar on gender and public space, and participated in various advocacy/protest activities in the city. This critical engagement with people across the spectrum added a dimension to our research, which would not have been possible through conventional isolated research. Thus, for us, participatory research was part of a philosophical and ethical position of engaging in a manner where the users of space are seen as partners in the process. This book is based on our research. It is as much about the city as it is about gender. It engages with feminist ideas in the context of twenty-first-century urban India and challenges the meanings attached to the concepts of risk, safety, modernity and citizenship. Our focus is on varied dimensions of class and geography as we traverse the city, writing about various places and people. Choosing to focus on one area meant leaving out several others. And so it is that men’s voices tend to be few and far between in this book. Caste is another category that we could not engage with substantively. These are significant omissions which we hope will be filled in by further studies. We are also aware that the section ‘In Search of Pleasure’ might be seen as stereotyping people and places as it attempts to provide a bird’s-eye view of the city. Some of the nuances and subtle variations may be lost, but this choice, to sacrifice depth to width, in covering more of the city and the women in it, is one that we made. We feel these limitations keenly as the ink begins to dry on our manuscript. In some cases, the women and the locations we write of are composites derived from our research, though our descriptions will ring a bell for most people familiar with these spaces or similar spaces in their own cities. Feminism in India and elsewhere in the world has often been accused of a lack of joy—the terms of description our undergraduate participants in workshops used were inevitably negative—manhating, anti-beauty, anti-family. While we disagree with these negative stereotypes, it is not untrue that even after decades of struggle, women cannot claim the right to fun. Even as many women today compete with men in the work space, when it comes to pleasure, the battle has barely begun. Our effort in this book is to foreground the fact that the seeking of pleasure, the succumbing to the seduction of risk are, when performed as acts of inclusion, profoundly feminist acts with potentially radical implications. Why Loiter? is written for a general reader, in the hope that questions of women and their place in the city become central to the complex debates on cities in general and Mumbai in particular. It is divided into four sections, with essays that focus on different facets of the debate, and can be read on their own. ‘City Limits’ lays out the central arguments of the book making connections between gender and safety, risk and citizenship, locating these against the histories and geographies of exclusion in the city. ‘Everyday Spaces’ examines the hardware of these debates, focusing on the role of the material infrastructure in reinforcing or undermining these structures of exclusion. ‘In Search of Pleasure’ maps the possibilities and impossibilities for different women in different parts of the city to seek unconditional fun in public space. ‘Imagining Utopias’ is an extended chapter that brings together the ideas of the preceding three sections to make a case for loitering as a fundamental act of claiming public space and ultimately, a more inclusive citizenship. Co-writing is a delicate dance in whose complicated footwork we found an unexpected pleasure. The devolution of responsibility made the act of committing ourselves to paper (or rather computer) seem less ‘risky’ and more pleasurable. This has been an exciting journey: moving from a focus on the right to safety as citizens to demanding the right to engage with risk and partake of the pleasures of the city through loitering. This book is the result of that journey. Its premise is feminist: the desire for gender equity in citizenship; its agenda is inclusive: the right of all citizens to public space. Shilpa Phadke, Sameera Khan and Shilpa Ranade Mumbai City Limits 1. Why Mumbai? ‘Bombay Girl’—a term that suggests a certain degree of insouciance about the world and your place in it—is the word that has been used to describe the Mumbai woman. She is the woman in the neatly pinned sari that defies the pull and push of the local train crowds. She is the one taking long strides in a nine-yard sari, carrying a heavy basket of fresh fish on her head, ready to take on anyone who dares come in her way. She is the one in the pin-striped suit, working on a laptop in the air-conditioned comfort of her car oblivious to the hooting, smoking traffic outside. She is the one in the bus on her way to college, wearing a tight T-shirt that reads ‘Eye-Candy’. She is the one on the Scooty expertly making her way through winding roads to the local bazaar as her pastel ridha billows around her like a halo.1 She is the one in the little black dress lounging in the latest club sipping a glass of Chenin Blanc, waiting for her date to show up. So will the real Bombay Girl please stand up? Of course, Bombay Girls are not any one thing—nor are they really girls at all. All the images of the Bombay Girl painted above have a grain of truth in them, but they are also incomplete. So if you go looking for Bombay Girls, you will encounter some that remind you of these but also some who are very different—and all of them tell you a little part of the story that goes into creating the multiple lives and worlds of Mumbai women. There is Sushma Pandit, chartered accountant and thirty-year-old mother of two, who is a regular on the 8.15 a.m. Dombivili local to CST. And there’s another Sushma Pandit, a sixty-three-year-old widow who cooks at five houses in Dadar Hindu Colony, determined not to be a burden in her daughter’s family. Or take Aliya Husain, the creative head of a television channel in Andheri, who has recently bought a plush apartment in Lokhandwala. Her namesake has a Master’s degree in history but would never dream of a career; she lives in Dongri, proudly running a household which consists of her businessman husband and two children. Sheetal Shah is a collegegoing student from Ghatkopar who has loud arguments with her mother over the tight T-shirts with provocative slogans she wears. The other Sheetal Shah is the same age and has just returned from her honeymoon in Switzerland to live with her husband’s extended family at Malabar Hill. Neelanjana Jadhav (IAS) is a deputy secretary and works at Mantralaya, the state secretariat. By a quirk of fate, her domestic help is also Neelanjana Jadhav, a.k.a. Neelu, a primary school dropout who commutes from Dharavi on the 11 Ltd. bus. Amy Pereira is one of the most popular mathematics tuition teachers in Bandra. Our other Amy Pereira will admit to being sixty-five, dresses in designer sarees, and is one of the city’s leading obstetricians, who has delivered more babies that she can count. Mehr Singh is a top model walking the ramp across the globe and is facing stiff opposition from her parents over her lesbian lover. The other Mehr Singh neé Batliwala is fighting a battle to inherit her parents’ beautiful apartment in Dadar Parsi Colony. These composites reflect the worlds of only some of the women in the city; their names are fictitious but their lives are not. The Mumbai woman then could be rich, poor; old, young, middleaged; a Hindu, a Muslim, Sikh, Christian, Jain or Buddhist; married, single, divorced, lesbian, hetero-or bisexual. She might be brahmin, dalit, bania (or anything in between) and speak Hinglish, English, Hindi, Marathi, Gujarati, Urdu, Tamil, or Bambaiya. Each Mumbai woman is a unique combination of these multiple identities. Contemporary Mumbai, considered to be India’s most modern city, is a metropolis of almost 5.5 million women and 6.5 million men.2 Mumbai has often been lauded in the media as the best city in the country for women to live and work in. The image of the Bombay Girl as much more assertive and independent than her sisters in other cities still holds. She is envied and derided in turn for her famed bindaasness, her ability to take on the world on her own terms and for simply living in a tough, even if friendly, city. In fact, so successful is this narrative of safety that the Mumbai woman’s access to public space is taken for granted. By ‘narrative of safety’ we mean all the ideas that people have, the stories they tell, and the beliefs they hold about safety that become part of the popular public imagination. So one might ask: why Mumbai? After all, in Mumbai, women are visible travelling in buses and local trains, shopping in bazaars and malls, working late in multinational offices as managers and in corner shops as saleswomen. As a television journalist who relocated from Delhi to Mumbai put it, ‘You girls don’t know how good you have it’.3 SO WHAT MAKES MUMBAI DIFFERENT? Perhaps it is its history of social reform in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Like Bengal, the linguistic region now called Maharashtra was deeply implicated in this movement for change. Here women were not passive beneficiaries of the movement; their voices were heard in public debates. Pandita Ramabai and Rakhmabai are only two of the women whose voices and pens expanded the spaces for women in the public domain. Their determination to be heard played no little role in the kind of visibility women in Maharashtra and particularly Mumbai enjoy today.4 Perhaps, the presence of a large and visible workforce of women across classes: white and blue collar, as well as the innumerable informal economy workers who fuel the mythical commercial energy of the city, also contributes to the image of Mumbai as a safe and friendly city for women. So pervasive is the presence of the ‘working woman’ on the city streets that it is largely unremarkable especially during the daytime. In this city, women’s worth as participants in the workforce is acknowledged and brings with it a certain degree of approval. This also means that a large number of shops and services stay open late at night, catering to the needs of these working women and creating bright, buzzing streets that add to a sense of comfort even after dark. Perhaps it is Mumbai’s famed urban transport, arguably the best in the country, that plays an important role in furthering Mumbai’s reputation as a safe city. Women are visible as commuters on the public buses and trains that run almost twenty-four hours a day. Each day, the bus transport system shudders under the weight of 4.5 million people and the suburban railway network literally bulges with 6.1 million commuters. By our calculations, approximately 15 to 20 per cent of these are women.5 In addition, the city has a large fleet of taxis and auto-rickshaws. Mumbai taxi drivers are often compared to their counterparts in London and New York for their ability to navigate the city, their friendliness, their loudly voiced political opinions and also their professionalism. Of course there are the odd instances of harassment, but these are few and far between relative to other cities. Perhaps, another aspect that makes Mumbai different is the fact that the city escaped the clutches of modernist planning. In other words, it was not imagined as a city neatly compartmentalized into living, working and entertainment zones. As a result, for most of the city, these functions overlap, sometimes spawning hostile battles as when a disco is located in the basement of a residential building. But it also means that most areas of the city are busy late into the night, creating a sense of being occupied and crowded, which can be a source of comfort. Certain new areas planned as business districts, on the other hand, do empty out after working hours, making them lonely, threatening and even eerie. Perhaps, none of these factors on their own would mean as much, but together they produce a sense of acceptance, even welcome, to women when compared to other cities. It might seem at first glance as though Bombay Girls have it all. So then, ‘Why Mumbai’? Because, as always, there is another side to the story. For, if Bombay Girls apparently have unrestricted access to public space, then why are there still so few of them as compared to men at any given place or time? Why do their large bags often hold pepper sprays, safety-pins, and knuckle-dusters? Why do women call home before they leave anywhere, especially late at night? Why do women feel the need to look like they are busy, either talking on the phone, or listening to a walkman when taking their morning jog alone? Look carefully and you will find that the women in the neatly pinned saris also wear equally discreet but nonetheless visible mangalsutras that mark them as married (and therefore spoken for). The women on their way to college in tight t-shirts also have their files clasped carefully to their chests in the classic posture of defensiveness. The corporate woman keeps her cell phone close to her, especially when she travels at night. The women in the ridha are only allowed their Scootys on the condition that the ridha goes with it. The women in the club have jackets tucked under their chairs that they put on the moment they step out of the club. Mumbai’s women too do not have uncontested access to public space. They feel compelled to demonstrate at any given time that they have a legitimate reason to be where they are. Commuting to work, ferrying children to school or going shopping are seen as acceptable reasons for women to access public space. However, being in public space without any apparent reason is not so easy even for the bindaas Bombay Girl. It is when women ‘get above themselves’, that the invisible boundaries become apparent. As every Bombay Girl knows, her freedom is subject to her knowing the ‘limits’, restrictions that often do not apply in quite the same way to her brothers. So although relative to their countrywomen in other cities, women in Mumbai are privileged in their access to public space, they still have to strategize, consciously or unconsciously, to negotiate public space. This is precisely ‘Why Mumbai?’ For if this is the standard of access to public space in the country, then perhaps we lack both ambition and imagination. 2. The Unbelongers There is a Bombay, a Bambai and a Mumbai. Just like there are many different Bombay Girls, there are many different cities in ‘Mumbai’. There is a South Mumbai and a North Mumbai. There is the Mumbai of high-rises and privileged wealth and the Mumbai of shantytowns and abject poverty. There is the city of derelict mills and the city of flashy malls. There is the city of the Marathi manoos, the Gujarati vyapari, the North Indian bhaiya and the Tamil babu. There’s the bania crorepati, the dalit safai karamchari, the Muslim powerloom worker, the indispensable multi-tasking domestic worker, the struggling actress, the Udipi restaurant waiter and the East Indian secretary. Each lives in his/her Mumbai, occupying anything from a few square feet of pavement to several thousand square feet of super built-up deluxe real estate. Each, moreover, has very different claims to the resources and spaces of the city. This disparity is not something new or even unique to Mumbai. Cities and definitions of citizenship have always been based on the principle of exclusion— on grounds of class, religion, race, age, sexual preference and property ownership, among others. You could have lived in Socrates’ Athens and not been a citizen if you were a woman. You could have lived in Julius Caesar’s Rome and not been a citizen if you were a slave. You could have lived in Portia’s Venice and yet not been a citizen if you were a Jew. Even historically, as urban geographer Don Mitchell (1995) points out, public spaces—whether the Greek agora (marketplace), Roman fora, or American parks, commons, marketplaces and squares— were premised on exclusion even as they mediated interaction between people. For instance, in Greek democracy, an individual was acknowledged to be a ‘citizen’ only if he fulfilled certain criteria. Citizenship was denied to slaves, women and foreigners, and though they may have worked in the agora, these groups were formally excluded from the political activities of this public space. Similarly, urban scholar Richard Sennett (1994) notes that in ancient Greece, citizens never comprised more than 15 to 20 per cent of the total population, which was approximately half the adult male population.6 Unlike ancient city-states, in modern politically democratic countries, citizenship is theoretically premised on constitutional and legal equality. However, in practice, criteria that are not very different from those of ancient times are used to determine who are legitimate citizens with rights to the city. In Mumbai today, the unbelongers are the poor, cast in the role of ungracious migrants who occupy the city’s spatial assets without officially recorded remuneration; the dalits and other lower castes whose presence is barely acknowledged, except grudgingly, when they take to the streets during Ambedkar Jayanti; and the Muslims, who are increasingly stereotyped as disagreeable outsiders, criminals and potential terrorists. Then there are the couples we don’t want sullying our park benches, the non-vegetarians we don’t want residing in our building complexes, the bhaiyas we don’t want selling our fish or driving our cabs, the gays and lesbians we don’t want corrupting our young, the North-Easterners we’d rather dismiss as ‘Nepali’, the elderly folk we don’t want occupying expensive real estate, the differently abled who we’d rather just ignore than allow any access to public space in the city, and, of course, in public space, all women without legitimate purpose, who should in any case be at home as good wives and mothers. This category all women includes women whose fathers, brothers and husbands are the undisputed belongers—middle-class, upper- caste, Hindu, young, able, heterosexual men. This might seem like an exaggeration since one sees these apparently privileged women in public spaces of the city as Mumbai strives to take its place among the global cities of the world. However, parallel to this visibility of the ‘modern’ Indian woman is an increasing neotraditionalism that locates women back in the private space of the home. This is buttressed by the increased reportage about public violence against women, which furthers the narrative that women are not safe in public spaces, sanctioning even greater restrictions on their movements. The increased exclusion of marginal citizens is reflected in the increasing public violence against those seen to not belong. This violence takes the shape of ousting people from their homes and places of livelihood, of tolerating brutal acts committed by private agencies and the state against certain groups and communities, and generally ignoring the basic needs of entire sections of the city’s population. Interestingly, this endemic violence is treated as separate from the violence against women and often elicits much less public outrage even though they are in fact fundamentally connected. The perception that these two kinds of violence are completely separate from each other is so well entrenched, that popular rhetoric actually places women’s access to public space in opposition to that of other marginal citizens. It is this perception that underlies fingers being pointed at North Indian immigrant men by some right-wing politicians after the much-publicized molestation of two young women near Juhu beach on New Year’s Eve 2008. Without awaiting any evidence, ‘outsiders’ were cast as the culprits responsible for ‘disrespecting women’ and ‘giving Mumbai a bad name’. The implication clearly was ‘remove these men from our city and our women will be safe’. Ironically, at least half the suspects who were apprehended turned out to be Marathi-speaking young men.7 The common belief that these two kinds of violence are separate and disconnected phenomena then allows the city to cast all women as potential victims and poor, dalit, Muslim and increasingly, North Indian men as potential perpetrators of violence.8 The success of this narrative is apparent from the fact that women themselves often identify the lower class, and Muslims as the threat to the city. At our focus group discussions, we often heard comments like, ‘Santa Cruz east is close to the slums, so it’s a very bad area’ or ‘I think Dongri, Bhendi Bazaar and Mohammed Ali Road are unsafe areas. The names of the shops are mostly in Urdu and quite unfamiliar.’ Similarly, the slum area of Dharavi is consistently cast as the image of what Mumbai does not want to be. In reality, both women and ‘other’ men are outsiders to public space, and the exclusion of women from public space is inextricably linked to the exclusion and vilification of other marginal citizens. However, the expressed concern for ‘women’s safety’ allows ever more brutal exclusions from public space in the guise of the righteous desire to protect women. This kind of unchecked violence is a more recent development in a city that once prided itself on its diversity and tolerance. Bombay/ Bambai/ Mumbai, all names for the city in English, Hindi and Marathi, respectively, became officially only Mumbai in 1995. This change has not just been nominal but reflects an increasingly conservative economy and polity, signalled by the communal riots that the city witnessed in 1992–93.9 Parallel to this have been largescale socioeconomic upheavals including a shift from a manufacturing to a service economy, most tellingly symbolized in the conversion of its historic mills to glitzy malls. Prior to this, the working class had a greater claim to the city than they do now. In fact, the textile mill worker was one of the classic images of the quintessential Mumbaikar, a claim that has been undermined by the near closure of the textile industry in the city.10 Some commentators perceive the 1992–93 Mumbai riots to be a watershed, shattering the vision of the city as a cosmopolitan melting pot.11 Other scholars argue that Mumbai had always been a fractured city, something the riots had only confirmed. These dissenting voices suggest that ethnic and caste divisions in Mumbai had in any case been organically linked with the economic structure of the city.12 It is debatable whether the riots caused the demise of the city’s cosmopolitanism or merely proved that this cosmopolitanism had not been uniformly shared by all social groups or classes. But what is evident is that they caused an almost irreparable damage to the social and political fabric of Mumbai city. Over the last decade, socio-economic changes have ossified these divisions in the city to make it not just anti-marginal citizens, but, more importantly, to make their exclusion more acceptable. There was a time when Nehruvian socialism and secularism created a national rhetoric of inclusion. Today, however, economic liberalization, globalization and communalization of the city have made it permissible for people to express their hostility in ways that would have been unacceptable earlier. The blame for poverty can now be laid at the door of the individual, absolving the state of any responsibility. This simultaneously gives the middle and upper classes a sense of righteous claim to what are in reality common resources, such as water and space. Even the dreamscape of Bollywood was more inclusive and had room for the poor.13 We have come a long way since then to a time when filmmakers often choose to shoot only in Switzerland or in high-rises and against the sanitized backdrops of gated enclaves. Today, the same Amitabh Bachchan, whose character cocked a snook at the rich, saying ‘In zameenon ka mol ho shaayad/Aasmaanon ka mol kya doge?’ (These lands may have a price/But what price will you give for the skies?) in Lawaaris (1981), is cast in an advertisement for a leading newspaper group which suggests that there are two ‘Indias’ in this country: ‘one that is straining at the leash’ and eager to forge ahead and take its place in the world, and ‘the other India that is the leash’, which is holding that self-propelling nation back. It is evident that by the latter the advertisement refers to the poor, the illiterate and the daily-wage workers who actually keep the city ticking.14 Mumbai then is no longer the city of dreams which welcomed everyone but is now actively hostile to the poor and the outsider. Mumbai’s slum-dwellers, numbering almost seven million, form more than 50 per cent of the city’s population. Yet, slum demolition drives are routinely undertaken, using the rhetoric of beautification. Hawkers are moved around like pawns on a giant chessboard under the pretext of zoning and cleaning up the streets.15 Bar dancers, and in fact dancing in bars, has been rendered not just illegal, but is surrounded by a problematic debate on morality and corruption of ‘Indian’ values. Increasingly, ‘citizens’ are only those who can afford to buy a range of goods and services from water and electricity to real estate and toilet cleaners (which, of course, suggests the possession of a toilet), and from credit cards and club memberships to luxury cars and LCD television sets. The greater an individual’s capacity to consume, the larger is ‘his’ claim to the city. As consumer citizens we are told we have rights: the right to consume good products, the right to legal redress when consumer products are sub-standard. The rhetoric of consumer citizenship has all but drowned out the faint voices that claim citizenship based on inalienable rights to public space in the city. This impulse to exclude the poor is reflected in the spatial geography of the city: in the increasing security that we see, in the high walls of gated communities, in the glass barriers of malls and coffee shops, that repel even as they seductively beckon. As anthropologist Arjun Appadurai (2000) puts it, ‘The rich in these cities seek to gate as much of their lives as possible, travelling from guarded homes to darkened cars to air-conditioned offices, moving always in an envelope of privilege through the heat of public poverty and the dust of dispossession.’ Nor is such a geography of exclusion and violence unique to Mumbai. Many cities of the world, including Sao Paulo, Los Angeles and Mexico City demonstrate high levels of economic and political discrimination that play out spatially as well. As Mumbai is poised on the brink of being recognized as a ‘global city’, the demonization of the poor is increasingly reflected in public policies that chart this new vision for the city. A classic example of this is a 2004 report, grandiosely called ‘Vision Mumbai’, which aims at making Mumbai a ‘world-class city’.16 It is a model built on the idea that we must make the city inviting and seductive to capital investors (and for this we must contain, if not entirely wipe out, the poor). The unarticulated implication is that otherwise the city and, by virtue of its location as India’s commercial capital, the country will fall into a decline, conceding defeat immediately to China. This might sound like a parody, but in the way the future of Mumbai is represented in the media, such thinking is unfortunately all too real. This is the city that would be Shanghai or Nanchung, anything but friendly to its poor. The poor are then pushed away to the city peripheries. Speaking of the situation in Los Angeles, which could apply to Mumbai as well, Mike Davies (1992) argues that not only are the poor increasingly sequestered in ghettos but their every attempt to use public space for survival purposes—for instance, by the homeless or street vendors—is criminalized. In Mumbai, this is mirrored closely by the closure of dance bars and the removal of hawkers that has been legitimized in the past few years. This demonization is also reflected in the narratives on safety articulated by combative middle-class citizens’ groups where the poor are seen as threats to the safety of the middle classes. Safety and order are prized in the new global city—both of which are presented as the antithesis of what is embodied, literally and metaphorically, by the poor: their slums are unsanitary, their homes makeshift, their bodies unhygienic, and their very existence a source of threat not just to the middle classes but to the city itself. If the growing affinity towards neo-liberal economics has virtually legitimized violence towards the poorest of the poor, then the deepening of right-wing politics in the country, and indeed the city, has normalized the hatred towards Muslims. The spectre of the communal riots of 1992–93, which sought to ‘cleanse’ the city of its Muslim citizens, continues to haunt Mumbai and shape its imagination. The Hindu right-wing garnered support across all classes in Mumbai by playing up the stereotypical image of the Muslim Other as a crude, Pakistan-supporting terrorist, and a promiscuous father of umpteen children.17 All Muslims were uniformly coloured, ignoring the reality that Muslims in Mumbai have always been a very diverse group.18 The last two decades have communalized relations between Muslims and other communities to such an extent that the Mumbai Muslim is now a pariah, increasingly marginalized from the mainstream, displaced and excluded from many of the city’s heterogeneous spaces. In the new spatially divided city, Muslims are progressively debarred from accessing mixed housing as well as from doing business in the more heterogeneous areas of the city. While Hindus continue to have the option of living in mixed areas, this choice has been increasingly denied to Muslims. When two reporters of a national television channel did an undercover story in 2004 pretending to be a Muslim couple looking for a flat, they were refused flats in several localities.19 Another young Muslim couple who looked for an apartment in Mira Road were told to go to only certain buildings at the other end where people like them stayed. ‘There you will feel at home,’ said the real-estate broker matter-offactly. Even the 2006 Sachar Committee report that investigated the status of Indian Muslims mentions that there is a marked reluctance on the part of house-owners to sell or rent out houses to Muslims and that banks discriminate against them in giving home loans. 20 So what does the exclusion of the unbelongers from city resources have to do with the exclusion of women? ‘Safety’ is the apparent reason why women are denied access to the public. The unarticulated reason why women are barred from public space is not just the fear that they will be violated, but also that they will form consenting relationships with ‘undesirable’ men. The focus on safety is rooted in conservative class and community structures, particularly those of ‘sexual endogamy’, which means that sexual relationships are sought to be kept within specific defined groups. This notion of safety encompasses not just sexual assault but also undesirable sexual liaisons even if they are consensual. The focus on safety rather than sexual endogamy, allows the erasure of questions of both class safety and unwanted sexual-affiliations across class and communal lines. Apparently there is almost as much shame in choosing the wrong kind of man as there is in being violated against one’s will. Women are then carefully monitored in an effort to not just prevent them from being assaulted but also to guard against their forming unsuitable alliances with men of their choice. This surveillance takes many forms—parental protection, fraternal affection, husbandly possessiveness, neighbourly nosiness or even the more formal strictures of the community (sharia jamaats, khap-panchayats and jatipanchayats) and state (constitutional laws and police acts). For women, decisions regarding their movements, partners, sexuality or even their own bodies are often not their choice. This then is the covert reason why women are prevented from accessing public space: the anxieties regarding the seductive prowess of this undesirable ‘other’, which could adversely affect not only the reputation of the middle-class woman, but equally significantly, that of her extended family and community. This control of the movement of women is heightened in communities that perceive themselves as being marginalized. This is because women, traditionally seen as unsullied by the vagaries of the outside world, often become the symbolic markers of a community, the keepers of its tradition, and the bearers of its honour. Controlling them then becomes synonymous with the protection of the community.21 For example, the increasing exclusion and ‘ghettoization’ of Muslims in Mumbai has had particularly adverse social, psychological and political consequences for Muslim women. Our research demonstrated that there are no significant differences between the access of Muslim women and that of women of other communities to public space. As with other communities, class, age, education, employment, and geographical location are equally important determinants of women’s access. Though the restrictions on Muslim women’s access to public space are similar to other women, the fact that their entire community is looked upon with hostility, and lives in fear of violence, means that they not only have decreased opportunities to venture out of community boundaries but also that their movements and behaviour are more closely policed by their families and community. For instance, an increased number of women report that wearing the burkha has become a pre-condition of their access to public space. At the same time, in a scenario where their community is under threat, women’s demands for equal rights are rendered secondary to proving solidarity with their community. The anxiety that marks Muslim women’s engagement with public space is then both the anxiety of being a woman in public, as well as the anxiety of being a woman of a particular minority community group in public. Thus, political and cultural safety as a Muslim is as much of a concern to them as the issue of everyday civic safety. Moreover, the marginalization of the Muslim community affects not just Muslim women. The stereotype of the aggressive Muslim male also impacts the access of non-Muslim women to public space. It is this fear of the imagined aggressor that women from other localities articulate when they say that Muslim areas are unsafe. Otherwise, going to Mohammed Ali Road to shop was something women from all parts of the city would do regularly without marking it as a Muslim area. Hindu right-wing agendas also consciously promote the idea that it is the Muslim man whom Hindu women have to fear and be protected from. This vision becomes not just the reason to exclude Muslim men from public space, but also justifies increased policing of all women. Safety for women is framed through the creation of a fallacious opposition between the middle-class respectable woman and the vagrant male (read: lower class, often unemployed, often lower caste or Muslim). By creating the image of certain men as the perpetrators of violence against women, women’s access to public space is further controlled and circumscribed and acquires an unquestionable rationality. In an interesting sleight of hand, both the person perceived to be the potential molester and the potential victim of the act of molestation are denied legitimate access to public space on these grounds. Women, however, often perceive some of those regarded as outsiders as representing the familiar ‘eyes’ on the street that urban scholar Jane Jacobs alluded to in the 1960s. For instance, one woman points out that the hawker who sold bhel across from her apartment building had been a familiar and therefore comforting sight for several years, unlike the security guards who changed every month. Similarly in our interviews, women commuters who navigated the area between the office district of Fort and Churchgate railway station lamented that ever since the hawkers vending books on the pavement were cleared in 2005, the area became uncomfortable after dark inducing them to walk through it at a faster pace. The argument that middle-class women’s, and indeed all women’s, access to public space will improve substantially if we remove lowerclass men from the scene is thus flawed even at the level of rationality. This argument is used to justify and reinforce various kinds of exclusions from public space, thus rendering both women and other marginal citizens outsiders to public space. Who then feels a righteous sense of entitlement to the city? The elite by virtue of their wealth and the middle classes who define themselves as ‘honest tax-paying citizens’ feel most entitled to the city and its manifold resources and services. This sense of claim is reflected in the burgeoning citizens’ groups—each seeking to ‘clean up’ their 200 square yards of the city. The emerging fractures in the city disturb them only so much as it upsets their sense of security and the conditions of their pavements. In the apparent struggle between rampant economic and cultural globalization on the one hand and reactionary religious and cultural fundamentalism on the other, the profile of the desirable subject of the city is getting more narrowly defined every day. Together, these seemingly opposite (but ironically compatible) forces are writing out the marginalized from the narrative of the city. And, as always, when groups are marginalized and direct or indirect forms of violence are inflicted upon them, it is women who are pushed to its precarious edges.22 The effect of exclusion on them is most telling, particularly in relation to curtailed access to public space and the policing of their everyday movements. Today, even though various gender-related issues are taken up in the media, the focus is on singular events and sensational stories. In this mélange, the fact that the various events are inter-linked is often lost. Issues like dress codes, the ban on bar dancers, the rape of a college girl, and the violence against women on local trains, all receive attention individually. In reality, these concerns are related not only to each other, but also to other processes of exclusion in the city: the demolition of slums, the attempts to clear spaces of hawkers, the prejudice against minorities and other ‘outsiders’, and in general the desire to erase everything that does not cohere with the vision of the city as a global sanitized space where things are kept safely in separate compartments. Once one understands that these issues are inter-linked in complex ways, it becomes clear that they stem from the same desire to maintain the status quo. Without subscribing to conspiracy theories, it is clear that this status quo is maintained by pitting excluded groups against each other. The focus on safety for women clouds the larger issue of civic safety—that is, safety for all. It not only ignores concerns of a class-or community-based safety, but in a bizarre twist actually presents these as the problem. Addressing the question of women’s access to public space then means engaging with the messy intricacies of layered exclusion. It means confronting head-on the fact that the exclusion of the poor, dalits or Muslims are not acts of benevolence towards women but part of larger more complex processes where one group of the marginalized are set against another in a battle whose strings are pulled by forces outside them. Placing these groups as the threat to women’s access only means that all of them and all women will continue to remain outsiders to public space. Women’s open access to public space then cannot be sought at the cost of the exclusion of anyone else. While there are particularities to women’s exclusion, women’s safety or access to public space cannot be imagined in the absence of a more general claim to city public spaces for all citizens. 3. Good Little Women A major Mumbai news story of 2005 was the banning of ‘ladies’ bars’ in the state by the Maharashtra government. These were ostensibly downmarket dance bars where alcohol was served while women danced to Bollywood film songs on a stage. The closure of these bars was represented in the languages of morality (‘The bars are corrupting our youth and breaking up our families’) and danger (‘The night is a time of unbridled sexuality’). And interestingly, the debate was chiefly centred on the figure of the bar-dancer.23 For, as we know, there are women in bars and there are barwomen. The former are consumers in upmarket nightclubs and pubs; the latter work in bars as dancers. Society does not view them similarly, especially not in public space. In the world of bars, the separation between women as consumers and women as performers or dancers reflects the divide between those defined as ‘good women’ and therefore to be protected, and those defined as ‘bad women’, from whom society needs protection.24 Narratives of safety for women in the city then, tend to focus on a certain kind of woman. She is the woman you see in advertisements peddling the joys of washing machines, cooking up noodles at a moment’s notice, or looking subtly sexy in her branded business suit. She is the woman racing to catch the 8.23 Churchgate fast train with a file tucked under her arm, haggling over the price of oranges at the local bazaar, or giving her children instructions on the cell phone. She is the woman advertisers woo, multinationals employ, and parents track down for their sons. She is the woman who can make the habitually apathetic Mumbaikars take to the streets in outrage when she is sexually assaulted. It is in her name that streets are sought to be cleaned up and public spaces sanitized. This is the woman you might imagine is the average Bombay woman. But this is only the simple picture. The simple picture presumes an unmarked ‘neutral’ woman in the city who must be protected from danger. It assumes that all women are the same, ignoring the differences that make for very distinct experiences of city spaces. This Neutral Woman is assumed to be not-lower-class, not-dalit, notMuslim, not-lesbian, not-disabled. But if one looks closely, the supposed average Mumbai woman is neither neutral nor unmarked. Hence, even though public discussions of safety might appear to be about all women, they tend to focus implicitly only on middle-class women.25 In the urban Indian context, this middle-class woman is further assumed to be a young, able-bodied, Hindu, upper-caste, heterosexual, married or marriageable woman. A man with her set of identities would have open, legitimate and unquestioned access to public space. The middle-class woman is then apparently privileged in every way other than gender.26 The middle-class woman is, in fact, implicitly central to ideas of Indian womanhood as the symbolic measure of many things. It is her education and employment that become the measure of a family/community/nation’s progress. Her clothing and visibility in particular places becomes a marker of desirable modernity. Her virtue, sexual choices and matrimonial alliances are fraught with questions of appropriateness and dogged by the assertion of caste, community and class endogamy. Those choices perceived as wrong or inappropriate may find sanctions ranging from ostracism to murder (as with the so-called honour killings). She becomes the canvas on which narratives of modernity and honour are simultaneously written. She is the bearer of respectability—of all moral and cultural values that define the society. Yet, it is this very notion of respectability that provides the rationale to foreground the figure of the middle-class woman and effectively evades any questions that might arise about exclusion based on grounds of class and community. This allows concerns about women to be only about middle-class women. For instance, the kind of attention paid and outrage expressed when a middle-class college girl was raped by a policeman on Marine Drive in April 2005 was missing when a teenaged rag-picker was raped, also by a policeman only six months later. For women, respectability is fundamentally defined by the division between public and private spaces. Being respectable, for women, means demonstrating linkages to private space even when they are in public space. The public–private divide is one that dates to the growth of the urban middle classes after the industrial revolution in Europe, when increasing wealth made it possible for more women to withdraw into a private domesticated world—making the privatepublic divide an aspirational value. Brought into the workplace by economic pressures in the late nineteenth century, working-class women were a visible presence in urban public spaces, engaging in activities that were regarded as lowly. For this reason, in the early twentieth century, middle-class women’s access to the outside world made it imperative that there be ways in which these ‘respectable women’ could be distinguished from the ‘non-respectable’—in this case the working-class women. Feminist historians have suggested that one of ways in which middle-class women did this was to carry with them the private modes of being into the public—that is to demonstrate through their body language that they belonged in the private.27 In the Indian context, historian Partha Chatterjee (1990) has argued that in colonial Bengal, nationalists selectively chose which notions of western modernity espoused by the British they would accept. While they were willing to accede to the superiority of the ‘modern’ west in relation to science and technology, the nationalists claimed culture and cultural identity as sites to be protected from the dominance of the colonizers. These sites became part of the private world of the home, away from corruption by ideas of western modernity. Women, who were the mainstay of this inner or private sphere, thus became responsible for preserving the sanctity of national culture. The division of ghare-bhaire—ghare, the inner world of tradition and continuity, which was the sanctum to be guarded by women, and bhaire, the hurly burly of everyday life which was seen as somehow impure and rough and had to be dealt with by men—was thus normalized. This did not mean that the woman could not be modern; in fact, it was important for the Bengali woman to be educated and have an understanding of the outside world, but this did not in any way take away from her primary feminine role within the home as mother and wife.28 Besides demonstrating that they belong in private spaces, women also have to indicate that their presence in public space is necessitated by a respectable and worthy purpose. Further, this purpose has to be visibly demonstrated to the effect that when any woman accesses public space, she has to overtly indicate her reason for being there. This demonstration takes many forms: for instance when standing alone at a bus stop at night, many a woman will accentuate her large bag, glasses or wrinkled end-of-work-day clothes to denote that she has been at (respectable) work. By using such performances of gender strategically and by demonstrating that they have a reason to be in public space, women create both respectability and simultaneously enhance their access to public space. This performance cannot be a one-time thing, as appropriate femininity has to be enacted again and again each time women access public space. The exercises we conducted during the course of our research clearly demonstrate the need for this repetitive performance of respectability and purpose.29 In one exercise, participants were given a drawing representing a typical residential neighbourhood street corner in Mumbai on a weekday evening where they were asked to separately locate a woman and a man in their mid-twenties (who were not from the same locality), waiting to meet a friend there, in places that they were most likely to be found. For most participants, locating the woman was obvious—she would usually wait at the bus stop. Locating the man was much harder because as they put it ‘men could be anywhere’. Discussion revealed that the woman was placed at the bus stop because then she would appear to be doing something, that is, waiting for a bus. So what would happen if she stood at the street corner? She would then be ‘out of place’, hanging around without an apparent purpose. To fail in the demonstration of purpose might leave the woman open to conjecture and, in some cases, the assumption that she is soliciting. When the tyranny of manufacturing purpose and producing an aura of privacy determines women’s access to public space, women who are inadequately able to demonstrate this privacy are seen to be the opposite of ‘private’ women, that is, ‘public women’ or ‘prostitutes’. This binary between the private and the public woman defines all women’s presence in, and relationship to, public space. The public–private division of space decrees that the rightful place of respectable women at night is within their homes and not in public spaces.30 This idea is used to separate ‘private’ (good) women, who are in their homes after dark, from the sexually and socially transgressive ‘public’ (bad) women who work at night. Ironically, in India, while sex work is not illegal, soliciting in public places is. Sex workers’ presence in public has always been illegitimate. Under the provisions of the Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act, 1988 of the Indian Penal Code, any woman appearing to invite the gaze, or ‘gazing back’ or even simply being in what is perceived as the wrong place, at the wrong time, in the wrong dress, or walking in the wrong way, could be booked for soliciting.31 For, if some women face the threat of being defiled in public space, then some (other) women are considered capable of defiling the ‘sacredness’ of public space by their very presence. ‘Respectable’ women could be potentially defiled in a public space while ‘non-respectable’ women are themselves a potential source of contamination to the ‘purity’ of public spaces and, therefore, the city. For the so-called ‘respectable’ woman this classification is always fraught with some amount of tension, for should she transgress the carefully policed ‘inside–outside’ boundaries permitted to her, she could so easily slip into becoming the ‘public’ woman—the threat to the sacrality of public space.32 The greatest source of anxiety around public space then stems not from the presence of sex workers or ‘unrespectable’ women in public space but from the potential of confusion in distinguishing respectable women from the unrespectable. For example, after sunset, parts of Mumbai’s Dadabhai Naoroji Road, on which the old Victoria Terminus (now renamed Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus) railway station is located, are peopled by sex workers soliciting business and other professionals usually on their way home from work. Both are dressed similarly in saris, salwar-kameezes or jeans. Both are seen to use cell phones, calling friends and family or communicating with potential clients of whatever kind. In that twilight time, literally and metaphorically, anyone could be anything. There is a distinct possibility of mistaking ‘good’ middle-class women for sex workers. The police, particularly, are very uncomfortable with this ambiguity as it undermines any control on women’s presence in public space.33 The public woman is not so much a direct threat to ‘good’ women as much as an illustration of what might happen to good women should they break the rules. Namely, if they break the rules, they are no longer deemed worthy of ‘protection’ from society. In fact, it is society which is perceived to be in need of protection from the risk of contamination that sex workers present. This perception of contamination takes many forms: the threat of sexually transmitted diseases and the threat to public morality posed by the very presence of the sex worker in public space. This not only justifies denying ‘respectable’ women access to public spaces but also serves to derecognize any violence that ‘non-respectable’ women might face in public. Sex workers, perceived to be engaging in work that is inherently risky and non-respectable, are therefore seen to be outside the purview of protection available to other women. Consider the Abhishek Kasliwal rape case in March 2006 in Mumbai. A fifty-twoyear-old woman alleged that twenty-seven-year-old Kasliwal— member of a wealthy business family—had raped her inside his car. A medical examination confirmed the rape and injuries sustained by her. The media showed great interest in the case until police investigations suggested that the woman was probably a commercial sex worker who was assaulted in the process of selling sex. The tone of the reportage and investigation then quietened down and eventually died out. Since the victim was possibly a sex worker, she was probably seen as less worthy of protection from a violent sexual assault and thus merited even lesser media and police attention.34 Not just sex workers, but even other women who appear to break the rules are deemed ‘unrespectable’, the antithesis of desirable womanhood. They are the women who defy the boundaries defined by families and communities and are not merely content playing the roles assigned to them. These include single, divorced and lesbian women, as well as those heterosexual women who cross lines of caste, community and religion for love and marriage. In a context where the family and community are all-important, izzat or honour begins to assume a value that supersedes safety— that is, from the perspective of communities and families, the preservation of women’s respectability and honour implicitly outweighs the value placed on their actual safety. Although statistics show that violence against women is far greater in private spaces such as homes, ironically, it is public violence that is the cause of greatest concern for society.35 Women then feel compelled to produce respectability and protect the ‘honour’ of their families even at the cost of their own safety. For instance, one young woman living in a predominantly Gujarati Jain building on Malabar Hill in South Mumbai would always be dropped off by her boyfriend at some distance from her building since her family did not know of his existence. She would then walk down the dark and deserted lane alone, however late at night. ‘Family honour’ demanded that she value her reputation over her actual safety. This is not something out of the ordinary, but an act that many women across the city perform without thinking twice. That this is so easily taken for granted demonstrates beyond reasonable doubt that visible virtue is valued over actual physical safety. Similarly, when a woman is raped, one often finds that the concern is less about bodily or mental harm to the woman and more about its repercussions on her reputation and honour. Shame appears to attach to the victim of assault rather than to the perpetrator of the crime. The reluctance to press charges in actual incidents of assault shows that families are more concerned with the ‘reputation’ of their women rather than the execution of justice. In the early 1990s, when a student was raped in Elphinstone College in South Mumbai by a group of other students, she was whisked away and never allowed to testify. In 2005, more than a decade later, another young college-going girl was raped in broad daylight by a police constable at Marine Drive. The young woman, in this case, after being assured of anonymity, did give evidence to the police that enabled them to prosecute the man, but this was partly due to the huge public outcry following the crime. What is of particular interest to us in this case is that there was a lot of public speculation about her companion, a young boy of the same age. While, on the one hand, the constable had apparently used the fact of her being out with a male friend to threaten her into the chowki; her parents almost appeared to condone this act of moral policing when they were quoted in the media, suggesting that their daughter did not know any boys. It seemed more important for them to prove that their daughter’s actions had been within limits of permissible behaviour than to demand justice irrespective of what she had been doing.36 So it appears as though the privilege of the middle-class woman in public space is only a veneer. The respectable middle-class woman is central to any discussion on safety and public space in the city. However, the demand for respectability means that she can only have conditional access to public space. The need to demonstrate respectability in her everyday actions and movements and the focus on sexual safety instead of real safety, actually denies middle-class women rights to public space. Furthermore, the insistence on respectability excludes other women who are deemed ‘unrespectable’ from staking any claim whatsoever to public space. For both desirable and undesirable female subjects, the insistence on respectability actively contributes to not just reducing women’s access to public space, but also compromises their interests when they do access public space. The inextricable connection of safety to respectability, then does not keep women safe in the public; it effectively bars them from it. 4. Lines of Control There was of course, no way of knowing whether you were being watched at any given moment … you had to live, did live, from habit that became instinct, in the assumption that every sound you made was overheard … every movement scrutinized. —George Orwell, 1984 Orwellian dystopias aside, women should come with a ‘comfortablebeing-watched’ gene encoded into their DNA. As foetuses, we are watched carefully for the presence of a penis and some of us never make it past that stage. As little girls growing up, we are watched as we sit, stand, eat and move. We are constantly told how to behave, walk and talk and as we grow older, we are ogled at by men of all ages: uncles, neighbours and strangers alike. So much so, that we learn to watch ourselves and internalize society’s gaze, which tells us how we should conduct ourselves as good little women. This act of constant self-surveillance by women produces what French thinker Michel Foucault calls ‘disciplined bodies’. Foucault argues that in spaces like prisons, schools, hospitals and asylums, where people are constantly watched by those in authority, the subjects—inmates, students, patients—no longer have to be monitored because they begin to monitor themselves. This produces a self-censuring gaze that Foucault calls ‘disciplining’.37 To fully understand the underlying reasons and implications of this disciplining, we have to remind ourselves that gender is not something we are but something that we do.38 Or, as philosopher Simone de Beauvoir famously put it, ‘One is not born a woman, but becomes one.’ Both men and women learn to perform their gender; boys learn what behaviour is appropriate to them and girls learn what constitutes feminine behaviour. As girls grow into womanhood, the body becomes the central medium through which these unwritten codes of behaviour are transmitted and memorized. The demure lowered gaze fixed at some point on the floor, the acquiescent nod of the head, the feminine swing of the hips, the closely held thighs and the modestly drawn-in shoulders are all written into our bodies by invisible hands and inaudible words so that we start believing that this is the way we are supposed to be. These ideas of appropriate gender behaviour are like mnemonics that we carry along with us lest we forget the realities of being women. The containment of a woman’s body is demonstrated by the very tightness with which she holds herself and moves. The notion that such gendered body language is ‘natural’ is reinforced by observing other women we encounter. For example, observing men and women in public transportation and on the streets of Mumbai, one notices the tentative and watchful manner in which women occupy public space. In BEST buses, the average woman will occupy the least possible space, rendering herself as inconspicuous as she can. This is often both a strategy to avoid groping hands and a reflection of women’s conditional access to public space. On the other hand, the average man will spread his legs out, occupy more than half of a two-seater in a bus and appear to disregard the people around him. At bus stops and railway stations, a woman will often hold a file, folder or book close to her chest, keep her eyes averted and seem to focus inward rather than outward. Men, on the other hand, stand in postures of control with legs held apart, look around with apparent ease and often occupy additional space with their arms. In every space, except perhaps sex-segregated spaces, men demonstrate greater levels of comfort, indicating a greater sense of belonging than do women. A woman’s awareness of her surroundings and other people in it, on the other hand, is acute. Women’s body language inside sexsegregated spaces, like the ladies’ compartment in the Mumbai local train, is different from that outside. In this ‘space’ women seem free to be what they want, sit as they like, even with legs spread out, and drop the masks demanded by the norms of modesty. The very presence of women in public is seen as transgressive and fraught with anxiety. For women, accessing public space is rarely a simple question of get-up-and-leave. It often involves the performance of unbelievably elaborate masquerades, undertaking complicated subterfuges and employing a range of accessories both consciously and subconsciously. As suggested earlier in the chapter ‘Good Little Women’, as outsiders to public space, women negotiate access by demonstrating respectability through signs that inextricably link them to the private space of the family and the home and by establishing an unequivocal purpose for going out in public. So long as women are able to convey the dominant narrative of gender—that they belong in private and not the public—they gain conditional access to public space. To signal refusal to adhere to these codes often invites censure, sanctions and violence. Prominent amongst the signs that women use to underscore their private location are symbols of matrimony worn on the body such as bindis, black-beaded mangalsutras around the neck, green bangles and red sindoor in the parting of the hair for Hindu women. These signify matrimony, perhaps, the most telling sign of respectability in the Indian context where marriage is assumed to indicate the safe containment of women’s sexuality. Even without the presence of a man by her side, a mangalsutra dangling on the bosom of a woman in the local train or bus acts as a ‘keep-off-I-am-taken’ sign in a cultural context where such signs are easily decoded and give women greater license in public space than they would have without it. In fact, sometimes even women who are not married wear a mangalsutra. As one American doctoral student told us, ‘I bought a cheap mangalsutra to wear when I travel late at night, as people presume I am a respectable married woman and harass me less.’ Marriage, especially coupled with appropriate gender performance, often gives women greater access to public space. In comparison, single women tend to be policed much more stringently. With these symbolic markers, women attempt to construct an image of themselves as models of ‘good’ Indian womanhood, who are worthy of being out in public and being protected. Such markers can create a bubble of private domestic space around women, even as they ‘transgress’ into public space. In some ways, it is also an attempt by women to self-police their bodies in public, or more importantly, to ensure that their bodies are ‘read right’ as being private bodies. The demonstration of purpose is another way in which women enhance access to public space while maintaining the cloak of respectability. Women manufacture purpose through the carrying of large bags, by walking in goal-oriented ways and by waiting in appropriate spaces where their presence cannot be misread. Women on their own in parks, for instance, produce a particular type of body language of purpose. They tend to walk a linear path, do not meet anyone’s gaze and often listen to a Walkman or talk on their cell phones. Their attention is directed inwards and they tend not to engage with the outside; the effort appears to be to legitimize their presence by demonstrating that they are walking for exercise and not for fun or social interaction. Similarly, when forced to wait in a public place, women will be careful about the kind of place they wait at, often choosing bus stops and railway stations as waiting points. Tied to these spaces is a sense of legitimate purpose—that of commuting. In other spaces, for women, the ‘act of waiting’ is fraught with anxiety, for to wait without an obvious and visible purpose is often perceived as soliciting. Since it is fairly legitimate for women in Mumbai to go to school or to work, women often use their location as students or workers to access public space. In other ways too, women legitimize their presence in public space by exploiting acceptable notions of femininity such as those which connect them intrinsically to motherhood and religion. For instance, the study of a large public playground in Kalachowki, a mill district in east Mumbai, shows that the low wall around the ground is largely occupied by men, often lounging around with friends or alone, at all times of the day, except around the time the school flanking the playground closes for the day and mothers coming to pick up their children take over the edge. These women often come much before school is over and sit around talking animatedly in groups or pairs. Many of them seem to have come earlier just to be able to spend some ‘official’ time in public space with friends. Women also use religion, and more specifically, religious activities and functions for which it is relatively easy to get family and societal sanction, as opportunities to enhance their access to the public. The demonstration of devotion and religiosity becomes an important marker of respectable womanhood. Visits to temples, dargahs and churches provide women a legitimate and everyday access to the world outside their homes. Sometimes, it even offers them the chance to break with protocols of time and space—such as walking on Mumbai streets barefoot at 2 a.m. on a Tuesday morning to be at the Siddhi Vinayak temple at Prabhadevi for the first arti at daybreak. Religious yatras and festivals may punctuate some women’s lives in significant ways by allowing special forms of access. This might mean a chance to beat your chest and wail mournfully on the streets during the taziya juloos on the tenth day of Muharram or a chance to walk uphill to Mount Mary’s church during the week of festivity in September. Or even the prospect of dancing with gay abandon under a starlit sky during Navratri. Women strategically use all these opportunities to expand their access to public space, their religious beliefs or lack thereof notwithstanding.39 To access public space then, women are expected to conform to the larger patriarchal order by demonstrating respectability and legitimate purpose. If women are seen to misuse the ‘freedom’ granted to them or to inadequately perform their roles as ‘good’ women, then the weight of the watchful gaze becomes visible in the shape of articulated codes relating to dress, norms of behaviour and modes of acceptable conduct. The less women appear to conform to unspoken norms of respectability, the greater appears to be the need for explicitly articulated codes. These codes are enforced at various levels by the family, community and even the state through implicit and explicit boundaries that delimit women’s access to the public. Most girls will remember the lines of control that were increasingly put in place as they grew older—as their brothers’ worlds expanded, theirs contracted. Daddies imposed the curfew, mummies made sure you sat with your legs crossed, bhaiyas saw to it that you came home straight from school, aunties commented if you romped around like a ‘tomboy’, and uncles reported seeing you with a stranger. Logic would suggest that women feel safest and will have most access to public space in the spaces most familiar to them. While women often record feeling physically safer in their own neighbourhoods, which are known to them and where they are known, this does not, however, translate into increased access to public space. In fact, spaces in which women are recognized as wives, daughters and sisters are often the most restrictive. Women who are seen as transgressive—usually single or divorced women, or those who openly flout social norms—are subject to hostility and harassment much more in their own neighbourhoods than outside where they are comparatively anonymous. Clearly, for women who do not conform, the spaces where they ostensibly belong are the most discomfiting.40 It is not surprising then that in our research many women from different kinds of neighbourhoods, across class and locations, said that they were more likely to retaliate to an act of sexual harassment in a neighbourhood which was not their own. One woman in Andheri said that she would ‘hesitate to make a scene in an area where I am known because people will talk’. She articulated what many other women across the city suggested implicitly: they feel more assertive in spaces where they are anonymous. Thus, rather than empowering women, the presence of insiders (and the pressure to demonstrate respectability: ‘good women ignore sexual harassment’) can actually prevent women from acting in their own defence. This is often tied to the notion that women invite trouble or are in some way to blame when harassment takes place. Creating an environment where women are forced to manufacture respectability might actually reduce women’s capacity to defend themselves. It is comparatively heterogeneous spaces that engender the greatest capacity to access public space. Single women who live on their own in Mumbai, away from families, are often the ones who articulate the greatest degree of unmediated access to public space. This comes not from a sense of safety—for as women on their own they have few support structures—but from the diminished need to manufacture respectability. This is not intended to romanticize the lives of single women in Mumbai who have to often negotiate suspicious landlords and the judgemental scrutiny of neighbours and housing colony managements who are intensely curious about whom they meet and how late they return home from work. The demand for women’s safety then is inevitably articulated in terms of surveillance and protectionism and contributes to reducing rather than expanding women’s access to public space. Dress codes that outline what women can and cannot wear are another example of such explicitly articulated regulatory codes of behaviour. In fact, when there are visible public attacks on women, the discussions inevitably focus on how the women could have prevented it. Clothing is the first target: its length, width, cut and even colour are debated in the blame game of national sexual politics—many colleges and universities across the country have instituted dress codes. In most cases, girls are prohibited from wearing jeans and sleeveless tops. In some cases, uniforms are prescribed for college students!41 It is a well-acknowledged fact that adhering to conservative dress codes does not provide safety—women in saris, salwars and even burkhas are also at the receiving end of sexual harassment on the street. What does change, however, is the crowd’s perception of the woman. Often, those women who are seen as respectable acquire a greater legitimacy when they protest against sexual harassment and tend to get sympathy and help more easily. Articulated codes also include those from religious communities. For instance, Muslim women have been at the receiving end of quite a large number of such codes. These regulatory codes, called fatwas in order to provide them with apparent religious backing, are handed out at the whim of local priests. Increasingly, in Mumbai and areas around, such fatwas and diktats are being issued through pamphlets and Friday sermons by local mosques. Many of these fatwas relate to women, specifically to their movement outside the house, such as visiting restaurants on their own and observing purdah.42 Such explicit codes reinforce the implicit rules and self-policing that women practise, and further limit their mobility. Given that the price of transgression is often violent—ranging from social ostracism and restrictions on mobility to physical assault and even murder—women’s apparent conformity to the codes of conduct is strategic. Many women, however, may covertly resist these norms. Openly challenging the lines of control would mean declaring outright war, an action that might actually further restrict their access to public space. When women follow the written and unwritten codes of gendered behavioural conduct, it does facilitate a certain kind of access to public space. For instance, playing the ‘good little woman’ often allows young women from conservative families to access educational and work opportunities, which might not have been open to them otherwise. These strategies then sometimes allow women to expand the boundaries of access both geographically and temporally. Yet, these acts of negotiation for women are a double-edged sword. On the one hand, they allow women to expand their access to public space, making them more visible in public, which in turn works towards legitimizing their presence in public. On the other hand, this access remains circumscribed because by acting in coherence with dominant gender structures, women reinforce them. Wearing symbols of matrimony might allow access through respectability, but it remains in the discourse of protectionism rather than rights. In other words, women endorse the same structures of discrimination that make their access fraught in the first place. Women push the boundaries in various ways: cajoling, threatening, inventing convoluted stories and lying in a bid to increase their access to the public, even when they do not use explicitly feminist language. These acts of ‘rebellion’ do contribute to pushing women’s claims to occupy public space. At the same time, these performances also put women into neat pigeonholes, which might work against their making other, more radical claims to the public. Seeking access as visibly respectable and feminine women also excludes all those women who do not wish to be ‘feminine’ or ‘respectable’ in their dress and demeanour. In the short term, tall tales and elaborate masquerades might allow us to seek pleasure in public space. In the long run, however, what we need are not covert strategies, but the demand for unconditional access to public space so that women may walk freely any time and anywhere in the city. 5. Consuming Femininity If there is a space where the otherwise frustrated question, ‘Where are the women?’ does not need to be asked, it is the modern shopping mall. You only have to walk into a mall on a weekday afternoon to see them. They are out there: window shopping, buying, eating lunch, drinking coffee or just strolling around. They are in the stores trying out clothes and making up their faces, and also in the food courts and fancy up-market restaurants, talking, laughing and gesticulating expansively. There are also college girls and professional women grabbing a bite in their lunch hour or sipping cappuccino in coffee shops, looking very much like they belong. One finds women here at night as well, though not in the same numbers, eating, drinking and looking very comfortable. Overall, women’s body language in malls demonstrates a sense of belonging that is not really visible in other kinds of public spaces. In these new spaces of consumption that have mushroomed all across urban India, middle-class women are not just welcomed, but ardently wooed. Malls go out of their way to entice women consumers—often with a designated women’s day in the week where free makeovers and gifts are on offer. Similarly, one sees women in discotheques and pubs, places where they are not just tolerated, but actively desired. Many discotheques and pubs will permit single women or all-women groups, but will not do the same for men. In a consumption-driven economy, shopping is an act that is both respectable and respected because consumption demonstrates power. The buyer therefore occupies a privileged position. While many women find pleasure in these spaces of consumption, access to these spaces demands a demonstration of their capacity to buy. As argued earlier, the idea of safety in the city is articulated mostly in relation to the middle-class woman. The desire to keep middle-class women safe in the limited public spaces that they are allowed in is then reflected in the range of tactics to keep out those perceived to be dangerous. Entry is regulated and concerted efforts are made to repel the poor, men and women alike: security guards, bouncers, high walls, glass barriers, and closed-circuit television cameras act to either intimidate people or actively deny them access. These malls are clearly private spaces, however much they may try to create the illusion of being public. The suggested safety of middle-class women in these new spaces of consumption defines particular locations in the city as being desirable for the middle class to live, work or be entertained in. Many women suggest that they feel safe in these spaces, although they too strategize in order to get home safely. The sense of apparent safety here is linked to the numbers of people and also to the ‘kind’ of people there—people who visibly belong to a certain class. ‘I love hanging out in the malls on my off days because here there are people of a better social class. I don’t have to worry about bumping into those “roadside types” so I feel more comfortable and am able to spend more time here,’ says a twenty-four-year-old airline stewardess. Clear, if unspoken, codes of dress and conduct underwrite women’s presence even in the malls.43 The performance of a ‘class habitus’ by women is required to underscore their legitimacy in these spaces. The term ‘habitus’ draws from the work of sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, who used it to refer to an individual’s way of being—which includes the way one stands, walks and inhabits space, and is reflected in manners of speaking, both of accent and idioms, as also in styles of dressing, eating and conversing with people. For instance, women often dress up to go to the mall or a coffee shop. In both these spaces, women are expected to demonstrate their class position through their dress and demeanour. This includes not just clothing, which shows their capacity to buy, but also body language that suggests a sense of familiarity, even boredom, with the mall space. There is a studied casualness in the way they carry themselves, as if they have been there hundreds of times. They step on and off escalators confidently, side-stepping half-fascinated, halfterrified, lower-middle-class families, who can sometimes be seen standing hesitantly at the bottom. There is a sense of comfort, even belonging, that women of this class demonstrate inside the mall, which is absent when they step back out on to the street. Moreover, the class habitus of the middle-class woman, as demonstrated in these new spaces of consumption, is very important in the construction of the global city.44 The logic at work here is one of legitimacy—the presence of respectable middle-class women provides the space with a certain aura of desirability. In the context of public space, the visibility of desirable women is both a sign of modernity and a marker of the ‘safety quotient’ of the space.45 Even as globalization in the shape of these new spaces of consumption offers women some limited access to the outside, it has also meant rising anxieties about its impact on ‘Indian culture’.46 This places a two-fold pressure on women: one, to embody the new vision of the modern desirable woman, well groomed and sexy; and two, to simultaneously demonstrate adherence to the norms of respectable Indian womanhood. For the urban Indian women, this paradox is often presented as offering the best of both worlds— Indian/traditional and global/modern at the same time—a tough balancing act, but nothing that cannot be achieved with a bit of creativity and ingenuity. The role of the media in the creation of this new modern, yet traditional, Indian woman cannot be underestimated. Mainstream films, television soaps and advertisements construct protagonists who appear to seamlessly straddle the stereotypically traditional with the clichéd modern: sindoor with mini-skirts or domestic goddesses with high-powered jobs. In the process, they manufacture a fictional pan-Indian image of womanhood. An example of this is the spread across the country of karva chauth, which is essentially a north Indian festival made popular by the hugely successful film Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge (1995).47 Mangalsutras, sindoor and choodas, popularized by television soap operas, have transcended their regional and community locations and may even be worn as accessories. It is no longer incongruous for women to wear the latest western designs accessorized with medallion-sized signs of Hindu matrimony. Talking to a group of women about the contradictions that this might suggest, one is often taken aback to hear vehement protests. ‘I am not embarrassed about wearing my mangalsutra with my jeans,’ declared one woman. ‘I don’t see what’s so inconsistent about it,’ argued another. ‘I can wear western wear but that doesn’t mean I have to let go of my Indian identity,’ said a third. But before one is tempted to view these as acts of subversion, it is important to note their role in women’s efforts towards manufacturing respectability. Here, the tools of modernity in the shape of attire and demeanour do not replace the traditional; they merely modify and mediate its expression. Cosmetic changes work, in fact, towards camouflaging structures of power that continue to determine women’s access to public space. This reveals the new personality of global capital—it is a chameleon that can change colours to suit local conditions. Today, it wears a sari so that it can take over a Mumbai market. Tomorrow, it will change into a kimono or a djellabah if it is necessary to break into another. Thus, while on the one side women are encouraged to participate in the new economy, they are simultaneously expected to demonstrate their femininity and adherence to ‘Indian’ tradition. For example, though women’s presence in these malls suggests a spatial mobility and women in advertisements are often represented walking on streets or driving luxury cars, the accent never shifts from their glowing skin and deodorized bodies. In other words, the pressure to be feminine and respectable never lets up. In the new global spaces of consumption, there are also new norms in relation to sexuality where the heterosexual couple is at the centre of all consumer fantasies. Most coffee shops in the city are dominated by young heterosexual couples. While some couples do consciously choose the more secluded tables; many appear unconcerned about public demonstrations of affection. The couples sit there, eat, drink, sometimes argue or have serious conversations. The space is clearly a private space where they are concerned. In the new spaces of consumption, a different morality operates—one that is removed from the dress codes of colleges and the antiromance tirades of public spaces such as parks and promenades. As long as they dress class-appropriately and look like they belong, the presence of couples and even their displays of affection are not looked at askance. They actually constitute part of the message that is sought to be conveyed: these are global spaces with global rules where one can leave behind the city and its parochial cultural contexts. Women on their own, too, often feel comfortable hanging out in coffee shops. These spaces allow them to be in ‘public’ in particular ways that permit visibility without compromising respectability. This place to hang out, however, comes with a price tag attached and we are not merely referring to the cost of the coffee. The private and the public are no longer clearly distinct, but embedded within one another in the same space, creating a potential ambiguity and, therefore, the need for women to continuously demonstrate their respectability. The fact that women’s access even to such new spaces of consumption is fragile is demonstrated by an incident in an upmarket neighbourhood of Mumbai. In May 2006, the local police in Lokhandwala in the suburb of Andheri alleged that they had received complaints that women sex workers were fixing up clients in the open seating spaces outside some popular neighbourhood coffee shops. As a result, the police prohibited the coffee shops from serving customers in the open area outside their restaurants. The connotation was clear: any woman sitting in these spaces could be perceived as soliciting. This accusation was met with outrage, but nonetheless many women stopped sitting outside.48 So fragile and shifting then are women’s claims to even these supposedly friendly spaces that they have to carefully monitor themselves even here. If we were conspiracy theorists we would argue that the space of a coffee shop offers the illusion of loitering while insidiously reinforcing gender roles and normative sexuality and class codes. Since we are not, however, we will simply say that as a step towards middle-class women’s claim to public space, it is a remarkably small one. It is important at this point to reiterate that new spaces of consumption like coffee shops and malls are not public spaces, but privatized spaces that masquerade as public spaces. Limited access to such private–public spaces creates a veneer of access for women, pre-empting any substantive critique of the lack of actual access to real public space. While these spaces might give individual women an opportunity to hang out, it does not in any significant way change the limited nature of women’s access to public space nor does it adequately challenge the dominant idea that women’s proper place is in the private. Even middle-class women who conform to normative ideas of respectability are at best invited into the ‘privatized’ public as consumers. Despite their desirability in these private spaces, women continue to have only conditional access, not a claim to public space. Privilege, then, does not bestow, on even limited numbers of women, unlimited access to public spaces in global Mumbai. 6. Narrating Danger Early on New Year’s day in 2008, even before the sun had dawned on the first day of the year, women across the country were already contending with public violence: In Kochi, two foreign women were molested on a beach. In Patna, more than fifteen boys from a medical college forcibly entered the girls hostel, ransacked it, and tried to molest the girls when the girls refused to party with them. In Pune, some men barged into a club, ‘passed lewd comments’ at women and got aggressive when others around them tried to intervene. In Kolkata, ‘groper gangs’ on motorcycles roamed Park Street and targeted and molested women who were out for the evening. In Mumbai, an unruly mob of almost eighty men groped and molested two young NRI women in Juhu, an upmarket suburb. The Mumbai incident—reminiscent of a similar incident in 2007 when a girl was molested by New Year’s Eve revellers at the Gateway of India—caught the public eye more keenly because a newspaper photographer captured the assault on camera.49 According to the news report published the next day, the women and their husbands had just come out of a five-star hotel at 1.45 a.m. and were walking towards Juhu beach, when a crowd of men began harassing them. Apparently, one of the women swore loudly at the men, who then surrounded them and molested them brutally, tearing off their clothes in the process. At this point, a passing traffic police van stopped and the police lathi charged the crowd to disperse it. The police took the victims to Juhu police station, but no case was registered. It was only two days later, after a formal complaint was recorded, that the police registered a First Information Report, which led to the arrest of about fourteen people. If the police failure to register a suo moto case was not surprising, then Mumbai Police Commissioner D.N. Jadhav’s comments the next day certainly were. His contention was that ‘Anything can happen anywhere,’ that ‘These small things happen in every society …’ and that ‘The media is creating a mountain out of a molehill’. As if this were not enough, he went on to assert, ‘Is your wife at home safe …? That’s because of our policing …’50 Commissioner Jadhav’s misplaced notion of what his policing duties involve apart, his comments indicate not just police apathy, but also a larger vision of where women really belong for, shockingly, Jadhav’s views seemed to be mirrored by many others in the media and public.51 This vision, that women do not have the right to be in public, also underlies the responses of both the perpetrators and the victims of the attack. The perpetrators, once out on bail, held a press conference where they defended their actions by saying that they were drunk but ‘under control’ (whatever that means) and were, in fact, being framed; it was ‘the girls who were drunk and smooching on the road’. They claimed no one was pointing a finger at the women. Ironically, the perpetrators were supported by middle-aged women neighbours protesting the virtue of their boys. The young women, both NRIs, disappeared from the public gaze after that night. They neither spoke to the police nor to the media who tracked down their ancestral village in search of a story. Despite the ‘boys’ claim that no one was pointing a finger at the women, the subsequent actions of both seem to indicate that the perpetrators felt well able to ‘show their faces’ in public while the women apparently felt compelled, like most women victims of such crimes, to hide their identities. Despite their good intentions, newspapers, television channels and radio stations over the next few days—in the name of factual reporting—talked of what the women wore, how late they were out, who they were out with, where they had come from, how much they had drunk, and the fact that they retorted in response to the taunts of their perpetrators. As a result, the message being sent to women in the city is clear: the public wants its women safe, but it thinks that the buck stops at the women themselves, it is up to them to know their limits. The police think it’s not their job to make sure the streets are safe for everyone—in fact, they believe it is the responsibility of women (and their families) to police themselves.52 When crimes do take place, like the New Year’s Eve molestations or the rape of a young college girl by a police constable on Marine Drive in 2005, the public perception of safety is impacted. Narratives of danger draw on particular ‘events’ of violence, assault and rape which then have implications even for those women who are not directly involved in them. When an international student was raped by six men in Mumbai after a night out with them in April 2009, several print publications published the victim’s FIR to the police, including many graphic details. This not only violates the privacy of the victim, making her vulnerable to identification, it also deters other women victims of sexual assault in the future from ever filing an FIR. Similarly, at a round table discussion, the Gender and Space project organized a month after the Marine Drive rape, young women who participated spoke of their fear that the wide publicity generated by the crime would lead to a greater policing of their everyday movements and decreased mobility in public space.53 However well-intentioned, media reportage of violent incidents tends to contribute to making the predominant discourse of women and public space one of inevitable danger. There is no denying that violence in public is real and threatening to women and it is not our intention to suggest otherwise. At the same time, the manner in which stories of violence are told and hierarchies of ‘danger’ are constructed magnifies the perception of the threat to women in public. For instance, a fatal drunken driving incident on Marine Drive, which also occurred on New Year’s Eve 2008, involving a few young men, got much less media attention than the Juhu assault. Most importantly, there were no reports or comments which even so much as hinted that the public space or being out at night on New Year’s Eve was unsafe for men. In comparison, the Juhu story got twelve days of intense coverage focusing on whether public space was safe for women in general. While it is important for public violence against women to be reported, at the same time, the tone and focus of media reportage may also create everyday anxieties that feed into the general perception which casts ‘public space’ as dangerous for women.54 The language in which public violence is described makes it sound more threatening. Even national papers that would describe themselves as liberal are not exempt from a certain tone of alarmism, even sensationalism. The following are only some examples of the headlines that proliferate in Indian newspapers: ‘For Women, Metro Streets are a Dark Alley’55; ‘Stalked in Sleepless City’56; ‘Fear Builds as 10 pm nears on the Railways’57; ‘BPO Murder: Outsourced Fear, women@risk’58; and ‘Acid Attacker, Train Vandals Still Roam Free’59. Not just the media, but also the general discourse on public space tends to disproportionately highlight the dangers waiting to jump out at women who dare to cross the prescribed lines. This misplaced focus on the dangers to women in public space contradicts two welldocumented facts: one, that more women face violence in private spaces than in public spaces, and two, that more men than women are attacked in public. The spotlight on public danger, somehow, perhaps without meaning to, underplays the seriousness of private violence. Though there are a large number of articles on domestic and other kinds of private violence, they somehow do not elicit the same kind of breathless sensational headlines. But, in reality, domestic violence and abuse of women, especially minor girls, has increased substantially. It is interesting to note that while the idea of the home as a space of violence and danger is still not easily accepted, the public is easily construed as a space of unmitigated danger that women would do well to stay clear of.60 On the other hand, though there are a substantial number of assaults on men in public space, they rarely elicit the kind of speculation that assaults on women seem to bring on. Because men are a taken-for-granted presence in public space, violence against them is represented generically. The spotlight on sexual safety locates sexual assault as a special type of crime, which underlines women’s particular vulnerability. The fact that not only women, but men, too, can be raped is something that finds little mention. Men are rarely represented as being in danger in public space, even when they appear to be specifically targeted, as in the case of the homicidal Mumbai serial killer dubbed ‘Beer man’ (because in some of his murders he left an empty beer can next to the body of his victim). The killer would sodomize his victims, usually lower-class men, before killing them. But there was very little allusion to the murdered men’s sexual vulnerability. There were a few other articles on this aspect after the alleged killer was caught—but those too very guarded and circumspect. Several men were killed between October 2006 and February 2007, but the case was never cast as being one of ‘poor men in danger on the streets of Mumbai’. On the other hand, random instances of violence that might not even be targeted specifically at women often get represented as ‘women in danger’. The ‘schizophrenic’ hammer man in Mumbai who attacked some women with a hammer in 2006 and robbed them is a case in point. While this crime did not appear to be targeted specifically at women, the media coverage highlighted only safety for women to the exclusion of all other matters. For instance, issues relating to mental illness and the state of our social and medical facilities to treat them were ignored. When a woman is attacked in a public space—the question of what she was doing there in the first place is inevitably asked, along with variations on the theme—what she was wearing and whom she was with. Concerns about the safety of women then are essentially about sexual safety and not safety from theft or accident or even murder. As discussed in the chapter ‘Lines of Control’, women’s sexual safety is connected not as much to their own sense of bodily integrity or to their consent, but rather to ideas of izzat and honour of the family and the community. The debates around danger and safety are usually constructed in the language of ‘sexual danger’ and focus on ensuring the sexual safety of women as defined by patriarchal families, communities and the state. Narratives of safety in the city also reflect a conservative politics articulated in the language of morality and respectability. Women are often blamed for violence that takes place against them, especially by the more conservative voices of the city. For instance, following the 2005 Marine Drive rape, one editorial read: ‘Be careful and the world will appear to be good … But in today’s superfast world … there are shards of glass on this modern path … we don’t see parents telling their children to tread carefully … There seems to be a competition among young women to show their undergarments in the name of a ‘below-waist’ fashion … To see girls dangle a cigarette openly is worrisome. If a man is provoked by such clothes, who can one blame?’61 Although this quote is not representative of the general tone of the media and is arguably its most conservative voice, media reports do tend to underscore not just the violence that ‘bad’ women face, but also the fact that even women who conform are not necessarily safe. The reportage of violence against women in public suggests that even when women conform to the rules, which demand purpose and respectability in public space, they are still in danger. The onus of demonstrating that they ‘did not ask for it’ continues to rest with women. The presence of these often apocalyptic visions of impending disaster have the effect of making women anxious, compelling them to strategize and negotiate every square foot of public space they access, all the while constantly looking over their shoulders, stalked ceaselessly by the ghost of past crimes. These accounts of danger reinforce women’s anxieties in public, thus normalizing women’s lack of access to public space. Furthermore, they have the added effect of sanctioning various kinds of restrictions on women’s mobility by rationalizing them as being for their own safety and well-being. For instance, an attempt to regulate clothing in colleges was justified in the name of women’s safety. One report was headlined: ‘Bombay University says mini skirt ban helps stop rape’.62 Or one news report citing the piece quoted earlier in this section is titled ‘Women inviting attacks’.63 Though this article makes it clear that it does not concur with the opinion expressed in the article, nonetheless the headline is misleading and sensational. Similarly, the international student gang rape story was reported explicitly on newspaper pages, including a news report that asked, ‘Why was she with six men that night?’64 In such a context, the location of shame on the victim discourages women from registering legal cases. This, in turn, influences the way in which women see themselves in relation to the city, reducing the claim they feel to public space. This affects not just the victims of violent assault, but all women who are reminded yet again that neither the city authorities nor the general public will protect their right to the city. Women are inevitably cast in the role of potential victims to be protected and the discourse becomes not about women’s right to the city, but about risk, fear and danger. Without putting the onus on the media to ‘change society’, what one might seek then is media coverage of violence in public spaces that is not skewed heavily in favour of violent incidents against women alone. In a utopian world, one might ask that reports interrogate the kinds of moral positions that underlie the desire for a particular brand of safety for women, which reduces rather than expands women’s access to public space. One might ask that stories seek to engage with women’s everyday interactions and negotiations in public spaces—such as streets, markets, railway stations, bus stops and parks—and, perhaps, even seek to understand women’s relationships with the city as processes rather than as events. One might ask that danger not be defined just as sexual danger, but, in fact, could be expanded to include the dangers inherent in the general loss of public space in Mumbai. And one may ask that the narratives of women and public space be not only about violence against women, but also about increased access and pleasure. In asking this, we speak not just to the media, who have unfortunately become everyone’s favourite whipping horse, but to the larger civil society that comprises aunts, uncles, parents and grandparents who often represent the middle-class moral minority which is likely to look at the headlines in shock and say, ‘But why on earth was she there in the first place at that hour?’ Is it too much to hope that in the foreseeable future the larger public discourse will ask, ‘But why on earth wasn’t she safe and what can we change about our city to make it safe for everyone?’ This is suggested not in order to render the city uniformly sanitized or to take away from the pleasures of urban risk, but because we believe that this change in discourse—that puts the onus on the city to be welcoming—is also one that will in fact allow women (and others) to court risk in the city. 7. Courting Risk It’s not just the media that is preoccupied with the issue of violence against women; the women’s movement in India is almost as culpable. Violence against women was the rallying point around which feminist political consciousness grew in the 1970s and 1980s. It was issues related to overt violence against women—rape, dowry murders and violent representations of women in the media—that became successful campaigns culminating in new laws and amendments to existing ones. It also led to structural and systemic changes through the judicial system in the setting up of family courts, special women’s courts, legal aid cells; and through the law enforcement machinery in the setting up of vigilance committees, allwomen police stations, special crime against women cells, family counselling centres, short-stay homes and awareness raising schemes. These campaigns petitioned the state to respond to acts of violence against women, placing women squarely in the role of clients, even victims, in the eyes of the media as well as the legal systems of justice. In the late 1980s, the women’s movement was forced to contend with issues of rising communalism (symbolized by the Shah Bano case) and complex questions around authenticity and cultural rights (illustrated by the mess that followed the Roop Kanwar sati).65 The 1990s brought with it more communal strife and the need to contend with women as victims of violence where rape had been used as a weapon against the ‘other’ community.66 Globalization has also meant contending with questions engendered by consumerism and the obsession with the body through beauty contests, consumer goods and advertising, where women have been seen as victims of a global capitalist conspiracy. In all these cases, women have been cast as victims, a strategy that has been successful in legitimizing women’s rights against overt violence. Women’s movement activism has also successfully focused on other kinds of violence against women through the denial of access to resources and brought on to the agenda questions of equality in education, employment, nutrition and health care. Consequently, the focus of the women’s movement in relation to public space has been on ensuring safety for women while accessing these resources, rather than on access for its own sake. Access to pleasure in public, even within women’s movements, despite ‘Reclaim the Night’ marches, has never really occupied centre-stage.67 It is seen as an add-on—if it happens, great, and if not, well—there are many things that are more pressing and important. Fun or pleasure as a reason to access public space has therefore never been a priority. Lesbian-Gay-Bisexual-Transgender (LGBT) activism in the late 1990s and early twenty-first century has by default brought pleasure into the reckoning—since same-sex desire and sexual activity can have no purpose other than pleasure. However, this is not centre-staged as the LGBT movement has sought greater legitimacy, focusing on questions of legality (through Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code) and violence against homosexual people by families, communities and the state.68 While foregrounding violence has put women’s issues on to the national agenda, it has also meant that violence becomes the only language in which one can engage with questions of gender in public space. Every time a woman steps out of her home, it is the spectre of violence that she must confront rather than any anticipation of pleasure. The modern imagination of city life is often about freedom and liberation and engaging with public space for the sake of pleasure. This has spawned a large body of literature—journalistic, fictional and cinematic—predominantly produced by men about men, which often idealizes an organic reciprocal engagement with the city. A case in point is the now iconic figure of the Parisian flâneur.69 Pleasure in the urban context has often been linked to the possibilities for taking risk, being transgressive, seeking anonymity and stretching the boundaries. However, these pleasures of risk are not equally available to everyone. Risk-taking is often considered acceptable, even desirable masculine behaviour. For women, on the other hand, it is not only seen as unfeminine, but as potentially the behaviour of a ‘loose’ woman. These spoken and unspoken restrictions then preclude the possibility of women seeking pleasure and thrills by accepting enhanced ‘risk’ as a possible negative outcome. For women, the potential negative outcome of courting risk lies not only in the threat of physical violence, but also in the risk of being seen as ‘unrespectable’ and therefore not worthy of protection.70 As argued in the chapter ‘Good Little Women’, the risk to women of seeking any kind of pleasure in the city includes not just the risk of physical assault, but also the risk to reputation if they are seen as transgressive. Because the city is cast as dangerous and because women are not allowed legitimately to take risks, even the simple act of walking in the streets without purpose is not easily achieved. Access to public space is even more fraught with anxiety after dark. For seduction, pleasure and risk are deeply interwoven with the night. Darkness represents the possibilities for both danger and pleasure—a device used by various popular narratorial texts, audiovisual and written. Historian Judith Walkowitz’s enticingly titled The City of Dreadful Delight (1992), chronicles the visual and textural pleasures and dangers offered to men and women in late-Victorian London. Many of these tales of murder, prostitution, theatre, clubs and pubs are associated with the night: a time–place to be both feared and desired. The darkness of the night presents the possibility of meeting the proverbial stranger, a source of both anticipation and anxiety. Men’s presence in the public at night reflects their capacity to enjoy the pleasures of the night even as women’s absence demonstrates the anxiety that keeps them away. The key to understanding this is in differing perceptions of risk. When men engage the night, they are taking the chance that they might experience something positive: pleasure, fun, exhilaration. They also risk hurt, injury or death. But, for men, an assault is just an assault— they may be injured, maimed or killed—their families will be upset, but their social status will remain unaffected. For women, the situation is quite different. When they do engage the night, even when they are not assaulted, even if they actually have fun, being seen in public space (especially while having fun) by the wrong people could adversely affect not just their own reputation, but also that of their families. If the spatial limits for women are drawn out through the private–public definitions, the temporal boundaries of a woman’s world are marked by the movement of the sun. To be out late after dark, particularly without male companions, is an act pregnant with fear, excitement and bravado, not short of outright rebellion, for women. Clearly then, courting risk is gendered—not only are men allowed more freedom to engage with risk, including the risk of partaking pleasure in the city at all times of the day and night, but engaging risk also has no adverse implications for their reputation and honour. In the preceding essays, we have argued that women in Mumbai have at best a conditional access to public space. Turning the safety argument on its head, we now propose that what women need in order to maximize their access to public space as citizens is not greater surveillance or protectionism (however well meaning), but the right to engage risk. For we believe that it is only by claiming the right to risk that women can truly claim citizenship. To do this, we need to redefine our understanding of violence in relation to public space—to see not sexual assault, but the denial of access to public space as the worst possible outcome for women. Instead of safety, what women would then seek is the right to take risks, placing the claim to public space in the discourse of rights rather than protectionism. What we might demand then is an equality of risk—that is not that women should never be attacked, but that when they are, they should receive a citizen’s right to redress and their right to be in that space should remain unquestioned. Choosing to take risks, even of possible sexual violence in public spaces, undermines a sexist structure where women’s virtue is prized over their desires or agency. Locating the desire for pleasure higher in the hierarchy of demands than the avoidance of sexual violence challenges the assumption that women’s bodies belong to their families and communities rather than to themselves. The desire to access the city for pleasure is not only a bourgeois desire, though it is most immediately meaningful to middle-class women; for lower-class women, it is often private spaces that are at a premium, while upper-class women tend to move from one private space to another, rarely accessing public space at all. The claim to seek pleasure in the city is also a deeply political one that has the potential to seriously undermine the public–private boundaries that continue to circumscribe women’s access to and visibility in public space. The claim to pleasure in public space as a right also implicitly means challenging the boundaries between respectable and nonrespectable women.71 At the same time, it is important to assert that risk should be a matter of choice and not thrust upon women through inadequate or short-sighted planning. The right to pleasure, by default, must include the right against violence, in the shape of infrastructure like transport, street lighting and public toilets. It must include policies that enable more sensitive law enforcement that recognizes people’s fundamental right to access public space. Demanding the right to pleasure does not absolve the city administration of the responsibility to provide these facilities. By our suggestion that courting risk might be a viable strategy, we are by no means suggesting that women, or indeed any individual, should be forced to take risks; at the same time, this should not curtail the freedom of those who wish to court risk. At no point are we ignoring or even minimizing the violence, both sexual and nonsexual, that might potentially take place in public. The fear of violence in public space is real. It contains the possibility of physical and psychological trauma. Nor is it our intention to romanticize risk itself, for as we have suggested, ‘risk’ is a term that is already valueloaded in terms of good and bad, and desirable and undesirable women. At the same time, the presence of violence should not preclude the possibilities for women seeking pleasure in the city. We also need to recognize another kind of risk—the risk, should women choose not to access public space more than minimally, of loss of opportunity to engage city spaces and the loss of the experience of public spaces. It also includes the risk of accepting the gendered status hierarchies of access to public space, and in doing so, reinforcing them. A Bambaiya phrase that young women in Mumbai use to describe their friends or peers who are rebellious is ‘usko bahut daring hai’ (she has guts), and its tone is admiring, not derogatory. This suggests that young women implicitly recognize that there is pleasure to be found in transgression. What women need then is the right to ‘dare’, to take chosen risks in an environment where their ‘daring’ is recognized and celebrated.72 Since the manufacture of the contraceptive pill, there has been a slow and grudging acceptance for women’s right to sexual pleasure.73 The question is: can we now claim the right to other kinds of pleasure? The pleasure of sitting on an unbroken park bench, reading a book or eating a banana (why not a banana?). The pleasure of walking the streets at night without anxiously looking over our shoulders. The pleasure of not having to change clothes in a car because your family thinks they are immodest. The pleasure of not having to hide when you enter your building at 2 a.m. in the morning for fear of what the neighbours will say. The pleasure of using a clean well-lit toilet at 4 a.m. in the morning on a public street without worrying that none will be open. This kind of pleasure can only come from the right to take risks without the fear of loss of reputation as good girls. Courting risk, that pleasurable dance of forward and backward, of negotiation and choice, is something that women have the right to. Courting involves active engagement, it implies a reciprocal relationship with the city—a relationship in which one approaches the city with the expectation of enjoyment. This is the right to which we stake a claim as women. It is time we claim not just the right to work, but also the right to play. Everyday Spaces 8. Public Space Public space in Mumbai is almost a contradiction in terms. In this city, public space is not just inadequate, it is also rapidly shrinking and increasingly being privatized. Every other footpath is being colonized by parking lots, every other recreational ground is under threat of being de-reserved for the benefit of the real estate mafia, every other open maidan is in the process of being gated and fenced in from the ‘public’. Perhaps, worse still, even the idea of public space is shrinking. Before going further, we should briefly clarify what we mean by public space.1 From our perspective, public space includes ‘functional’ sites such as streets, public toilets, bus stops, railway stations, marketplaces and modes of public transport, such as buses and trains, as well as recreational areas, such as parks, maidans, waterfronts and promenades. Privatized recreational spaces such as shopping malls, coffee shops, restaurants and cinemas are increasingly being represented as the new public spaces of the city. Many women, particularly middle-class women, told us repeatedly that they often spent their leisure time in such places and viewed them as substitutes for public spaces.2 These privatized public spaces create the illusion of access, courting as they do middle-class consumers. Yet, it is imperative that we distinguish these spaces from real public spaces for in the guise of publicness, these private–public spaces are steadily replacing public–public space, such as when spaces ear-marked for parks and playgrounds are sold for commercial use on the premise that even the existing parks are not being used. Given the sheer shortage of public spaces in the city, one might argue that the lack of access to public space is true not just for women, but for all citizens. While this is accurate in a broad sense, it is also true that women are particularly affected in ways often connected to their gender. Spaces (and places) are not neutral grounds nor are they equally designed for everybody. As social scientists and geographers might put it, space is not a given but is ‘constructed’. Space is not a passive backdrop against which human activities are played out but is an active participant in the making of a particular social order. Just as much as the presence (or absence) of people, what they do and how they do it influences the tenor of a space; so also the kind of space and the way it is made (location, facilities, design) affects the way people inhabit it.3 In other words, people make space as much as space makes people. Moreover, space is what one might call an ‘embodied experience’, that is, it is experienced viscerally through the bodies we inhabit: male, female, rich, poor, old, young, white, black, brown, able-bodied and differently abled. It is not a neutral void to be filled up but is differently defined by the various people who inhabit it. This means that men and women experience it in different ways, making any given space integrally gendered.4 Across geography and time, men and women do not have the same kind of access to space, nor do they use it in quite the same way. Further, constructions of gendered space are not the same everywhere and they also change over time. Nonetheless, it is possible to generalize that across locations and time, one specific characteristic of gendered public space is that it often excludes women. This exclusion operates in complex ways so that different women have differential access to public space. Older women may have greater access to public space than younger women. Women may have access to certain public spaces in the daytime but not at night. Restrictions may be relaxed at special times such as festivals or become stricter in response to reports of public violence. So far, when we have talked of the right to ‘take risks’ in public space for women, we have interrogated social norms and ideologies that privilege safety over access to public space. However, access to public space is dependent not only on the ‘permission’ to be in public, but also critically on the availability of actual material facilities, which make it possible to use these spaces. That is, it is not just the attitude to women in public that prevents women from accessing public space, but also, quite literally, the availability of public space or the lack thereof, as well as the infrastructure and design of the city. In this section, we look at the role of city administrations, infrastructural facilities and design in producing public spaces that either facilitate or prohibit risk-taking. The relevant question to ask here in relation to risk in public space is whether these risks are imposed or chosen. For instance, the risk of accessing public space, in a broad sense, is chosen, but the risk associated with the lack of infrastructure like good roads, street lighting and adequate public transport are not a matter of individual choice and imposed through decisions made by city planners. This significant distinction needs to be made upfront—when we ask for the right for women to take risks in the city, it is chosen risks we speak of, not the risks imposed by the lack of adequate infrastructure. Our desire to court risk in the city does not preclude the explicit understanding that the city needs to provide its citizens with infrastructure of all kinds—including transport, toilets and parks—to enhance access to public space. If one were to accuse planners of not providing adequate infrastructure for women, they might respond by saying that there aren’t that many women in public space in the first place. In the case of public toilets, they might argue that there are very few public toilets open at night because there aren’t so many women out in public at that time. However, if women were to be asked this question, they might invert the equation and argue that the lack of public toilets makes it even harder to access public space at night. One might contend that changing people’s attitudes is usually a slow process, but the provision of infrastructure can be a simple one-time administrative policy decision.5 In other words, if public facilities were provided 24/7 it would send the message that women are expected to be in public space anywhere, any time. For example, in Mumbai, the presence of reserved compartments for women in local trains clearly enshrines their right to be in that public space. Public spaces and infrastructure are usually designed for an abstract ‘generic’ user. In the context of an ideology that deems women’s proper place to be at home, this imagined ‘neutral user’ of public facilities and infrastructure is invariably male. Not just gender, but all manner of politics—class, caste, religious and sexual, as also physical ability—are part of imagining this ‘neutral’ user. The prototype user then is not just male but also middle or upper class, Hindu, upper caste, able-bodied and heterosexual. Others who use these spaces and infrastructure just have to adjust and make do with what they get. So the physically challenged have to make do by not being able to access most public transport facilities; the old have to make do with negotiating the high steps of subways and foot-over bridges; the poor have to adjust to paying up for public spaces they once had for free; the lower castes and Muslims have to be content with being allowed just the margins; the gays and lesbians have to pretend to be invisible; and women have to learn extreme bladder control and to negotiate dark streets and unfriendly parks. Infrastructure that privileges the needs of one group stands to reinforce the status quo and promotes an unfair hierarchy. Infrastructural provisions that discriminate against some groups not only create everyday problems of accessibility for them but also reflect their marginalized position in society. When groups are denied access to public space, this actually leads to a double discrimination since rendering them invisible also reduces their opportunities to publicly lobby for change. There are two ways in which the problem of unequal access is usually dealt with. One is segregation or reservation of certain areas for the ‘marginalized’, and the other, particularly in the case of women, is increased security. Both these methods, although apparently benign, raise complex questions in any discussion of infrastructural provisions. Reservation in general is often seen as contradictory to the idea of equality.6 If men and women are indeed equal, should they not be treated with absolute equality? Are we not institutionalizing difference by making such classifications? It is here that distinguishing between ‘formal equality’ and ‘substantive equality’ might help illuminate the issue of what constitutes equality.7 Formal equality would mean simply the constitutional right to travel by public transport but would not address actual conditions of access, when commuting by train for instance. Substantive equality, on the other hand, implies a commitment to equality of access and not merely the opportunity to do so. In other words, the question is not whether everyone—men, women, children, the elderly and the disabled—can theoretically travel on the 9.20 a.m. rush hour local train, but whether all of them have an equal chance of actually getting onto the train. It is the latter we argue that constitutes real equality in this case. Reservation then is a proactive policy intervention to narrow the gap between theoretical and actual equality. This means that once this gap is closed, we would no longer need such provisional spaces of reservation. The second method popularly employed to facilitate the access of women to public space is the provision of security. This brings the double-edged debate on surveillance centre-stage. The increased policing in the women’s compartments of suburban railway trains in Mumbai, in response to a spate of attacks against women in the year 2000, exemplifies this conundrum. While some women commuters did recount feeling ‘safer’, others were wary of the policemen themselves. Interviews with policemen assigned to guard these compartments revealed that they also had mixed feelings on the subject. Some were affronted by a task that they saw as not being their job and felt demeaned by the task of protecting women. Other responses were benevolently paternalistic, suggesting that women are vulnerable and under threat and ‘It is the duty of the government to protect them as they are weak.’8 There also seemed to be an unspoken sentiment that perhaps women who were out late at night were transgressing acceptable boundaries and therefore ‘asking for trouble’. This sentiment underscores the fact that women’s behaviour in public is watched, further reinforcing their need to manufacture purpose and respectability. Safety, as we have argued, can and does easily slide into a protectionism that restricts women’s access to public space and does so with a rationality that is unquestioned. At the larger city level too, while it is vital that city administration and policing is efficacious, security that is provided with the aim of policing the behaviour of citizens can be as problematic as inadequate policing. Women report that lighting often adds to their sense of comfort and safety on the streets. At the same time, lighting can also slide into becoming a panoptic, all-seeing gaze that monitors citizens and can always be used against them if they appear to be transgressing the parameters of socially acceptable behaviour. This will happen when state structures do not involve women in the solutions they create or when they do so without addressing fundamental questions regarding equality of access. Questions of infrastructure then need to be examined within the framework of rights and citizenship and not through a perspective that frames women as victims or clients. In our fantasies, the words ‘public space’ conjure up images of open expanses, maidans, parks and waterfront promenades where all kinds of people can come to meet, walk, run, or play games, read books or write, where mothers can bring children, senior citizens can walk dogs, the differently abled can find a smooth pathway to manoeuvre their wheelchairs, those of alternative sexuality can express affection and everyone can just be themselves. In the following chapters, we focus on this need for infrastructure, drawing attention in turn to the over-loaded public transport system, the almost invisible toilets and the dying parks of the city. In all these spaces we also explore how design can make a difference in shaping accessible infrastructure and public space. Public spaces reflect the city’s attitude to its citizens. The presence of sensitively planned infrastructure and welcoming welldesigned public spaces are a measure of its inclusiveness. We believe that the right to the city means a right not only to inhabit urban spaces, but also to participate in a city as an ongoing work of creation, production and negotiation.9 The lack of infrastructure not just amounts to a denial of access, but actively prevents people from participating in shaping the future of the city. The real test of successful design and planning of public space lies in how much people are able to claim it as their own and adapt it to their individual and collective lives. Public space represents what the city might mean for its citizens— the possibilities it creates for them to become part of the city, to belong to it and have it belong to them. When we say ‘become part of the city’, we mean in a visceral sense—where citizens can go out there and claim the city with their bodies, walking its streets, strolling along its edges, watching its movement and partaking of the thrills of risking pleasure in the city.10 Taking risks is only possible, especially for women, when the infrastructure is in place—when the streets are well-illuminated, the public transport system runs day and night and when safe toilets for women are accessible at all hours. These might not be adequate by themselves, but they are essential conditions for making city public spaces more accessible to women. These facilities are not favours bestowed by the state but the right of all citizens. 9. Commuting Many people, when asked to draw a map to guide a friend visiting the city, often forget to draw the sea, but inevitably draw the railway lines snaking across the city. The Mumbai local train network and the red BEST (Bombay Electric and Suburban Transport) buses have by now become iconic symbols of the city, the sheer grit and determination of its people, their unbeatable spirit and the method behind its madness. The three north–south railway lines that connect the city are the lifelines that structure its citizens’ perceptual map of the city. Similarly, the local transport buses are a ubiquitous sight in the city, covering every nook and corner, and it’s not unusual to find people proffering bus numbers as guides when giving directions. Paeans have been sung to this transport system and films have been made immortalizing the local trains in Mumbai.11 Even academics, writers and journalists have given it the approving nod.12 Travelling with confidence on the local trains often marks a rite of passage for those who want to belong to the city. A woman who moved to the city for work talked about how the ability to negotiate local trains: their timings, varied platforms and the general hurlyburly of crowds gave her a sense of confidence and self-possession. ‘There is something essentially Bombay, about local train travel,’ she said, ‘and now that I’m part of it, I feel like I belong.’ Studies across the world the world demonstrate that access to public transport is a significant factor in enhancing women’s access to public space.13 The thriving public transport system of Mumbai is a case in point. The presence of a system of usable ‘public transport’ is what substantially distinguishes Mumbai from other cities, particularly for women. This is not meant to imply that no public transport exists in other cities, but certainly, only in a few other Indian cities do middle-class women continue to use public transport like buses and trains when they can afford rickshaws, taxis or even private cars. This for us is the true marker of good public transport— when people begin to prefer it to other forms of commuting. In fact, Mumbai has always had the distinction of having over 80 per cent of its commuters use mass transportation. Local trains (on the Western, Central and Harbour lines) and BEST buses run almost twenty-four hours a day.14 The large workforce of women in the city, mostly middle and lower-middle class, rely on this network as means of access to education and employment, often travelling up to forty kilometres to and fro every day. Yet, the numbers of men, both commuters as well as staff, far outnumber women. In BEST buses, the drivers and bus conductors are largely male. In August 1998, BEST inducted seven women conductors into the service but this experiment failed for several reasons. From a conservative cultural perspective, their work and the contact with unfamiliar male commuters that it entailed, was seen as unacceptable. From an infrastructural perspective, for over six months, the BEST failed to provide the women with separate changing rooms or toilet facilities, making their situation extremely uncomfortable, especially in the face of resentment and suspicion from their male colleagues. No women have been subsequently employed by the BEST on buses.15 A similar predominance of male staff assails the train services as well. In Mumbai, as in some other cities of the world like Cairo, there are compartments and seats reserved for women in the local trains and on buses.16 Many Mumbai women commuters will quite candidly admit that what enables them to use local public transport services is this gender segregation. Yet, the reservation of seats for women remains a subject of passionate discussion. When we debate the need for ladies’ compartments with students, there are heated arguments on either side—those who believe that reservations are a legitimate means of affirmative action and those who think they stink of parochial patronizing. Whatever side of the argument students are on, eventually, almost everyone comes around to accepting that the existence of the ‘ladies’ compartment’ is one of the most important reasons why local trains are used extensively by women commuters. Without these, given the crush of male bodies in the overcrowded general compartments, it is unlikely that many women would have the opportunity to access public transport, and by extension, to access the public sphere.17 The ladies’ compartment can also get crowded beyond comfort levels during peak hours, but because all the densely packed bodies are female, and are assumed to be heterosexual, this is not considered threatening.18 The reserved seats on buses, however, drew a more mixed response when they were first introduced in the late 1990s. Until then, buses had been entirely mixed use and the introduction of reserved seats for women was accepted grudgingly, not just by men but also women, who saw it as demeaning and almost pre-modern.19 However, today, that these seats ‘belong’ to women is generally taken for granted and men often either do not use these seats at all or silently rise when they see a woman standing. Women also continue to sit elsewhere in the bus. The segregation of spaces based on gender in public transport does underline and reproduce gender differences. Yet, in a context where women are far outnumbered by men as well as socially and politically marginalized, the provisional presence of reserved seats in fact evens out some of the odds against women. Further, some families would not allow women to travel without the provision of these sex-segregated spaces. The question once again is of articulating the difference between formal equality and substantive equality, that is, the difference between ‘all people may get on to the train’ and ‘all people actually get on to the train’. In spite of its critical importance in the daily lives of many women, the ‘ladies’ compartment’ is hardly a homogenous space of feminine (much less, feminist) utopia; in many ways, it is also a highly contentious space. Much has been said about the camaraderie in these trains where women cut vegetables together, sing bhajans, knit, sew, celebrate festivals and counsel each other. At the same time, women commuters testify that women are not immune to the arguments, tensions and hostility that train travel inevitably generates in impossibly overcrowded conditions. Beyond these everyday external pressures also operate a range of other prejudices. Among these are the pollution taboos, which mean that fisherwomen who try and use the ladies’ compartment at times when the vendors’ compartment is crowded with male vendors are met with hostile demands that they leave. Commuters in the first class compartment are very aggressive in barring the entry of others ‘not appearing like first class pass or ticket holders’, that is, lower class in habitus. Hijras are met with annoyance mixed with anxiety.20 Transgender people and lesbian women who dress ambiguously face reactions ranging from confusion to hostility. Women who do not look indisputably feminine are therefore directly or indirectly excluded from these spaces. The ladies’ compartment then becomes a space that can only house women who obviously look like women!21 While Mumbai’s transport network might be regarded as the best in the country, it is still far from satisfactory when it comes to fulfilling the requirements of commuters. All public transport facilities of the city, particularly the suburban train network, are stretched beyond capacity. A suburban commuter train meant for 1,710 commuters regularly carries up to 5,000. This situation is called Super-Dense Crush Load, that is, with fourteen to sixteen standing passengers per square metre of floor space.22 But numbers don’t even begin to explain just how crowded these trains are. Sardines probably have much more space in a tin than local train riders. Yet, so mythologized is the city’s transport system that even this subhuman level of travel doesn’t really rile anyone enough to do anything concrete about it. Despite the many hardships attendant to commuting in this city, there is certain insouciance among commuters in Mumbai, both women and men, that has its roots variedly in optimism, resignation, lack of choice and de-sensitization. In addition to inadequate transportation, our extensive ethnographic studies on public transport also revealed that the provision of transport-related infrastructural facilities like adequate toilets, lighting, foot-over bridges and signage is grossly lacking.23 Our research at railway stations led us to undertake a study of lighting levels at thirty-five suburban stations along the Central Railway—both Central (Main) and Central (Harbour). Our intention was to study lighting not technically in terms of measurement of lighting levels, but through a comprehensive survey based on our own subjective perceptions. Lighting levels were assessed for adequacy both in terms of brightness and the context. That is, corners, staircases and foot-over bridges may need more than average lighting as these tend to be perceived as dangerous spaces by women. All stations were not uniformly dark, but some broad areas of concern emerged. Toilets were often dimly lit or completely dark; the staircases on the foot-over bridges often had only one tube-light, which was grossly inadequate. Exits were rarely lit at all and most illumination usually came from nearby shops. Unused platforms at stations tended to be dark and threatening, all of which made access more difficult.24 A more fundamental problem is that public transport in the city gets short shrift when it comes to planning more services and facilities as compared to private transport. Increasingly, policies tend to focus on private transport and road infrastructure intended for them, such as flyovers, at the cost of improving the stretched public services. This lopsided development continues despite the fact that a majority of Mumbai’s commuters use mass transportation.25 This tends to affect women more because it has been observed that even in families which own private vehicles, women are still the ones more likely to use public transport. The city’s mass transport system has given Mumbai women, across all classes, an exceptional opportunity to access the public. They are an excellent example that shows that effective infrastructural provisions can, in fact, make a dent in pervasive ideological structures and provide better access to public space for women. Many women commuters acknowledge this contribution in glowing terms. But that same system is now under strain and the focus on private transport is not helping matters. Having recognized the invaluable contribution of the existing public transportation to women’s access to public space, it is still possible that an unreflective hubris will allow these long-fought gains to slide away. It is critical then that the existing system is augmented and loopholes are plugged to ensure that even more women can get better access to public space. A high-quality, affordable, efficient and egalitarian public transport system has the potential to transform the city, making it ‘global’ in ways that glitzy glass and chrome buildings cannot. Such a system has the capacity to bring on board not just women and other marginal citizens, but also those who might currently travel by private vehicles. Bringing together people across class on a mass transportation system might be one way to begin imagining a city where hierarchies are not determined by people’s inability to commute. 10. Peeing Scene 1: Waiting at the bus stop, she presses her thighs together and draws in her pelvic floor muscles again. As the bus nears, she anticipates the added torture of its swinging motion to her already overstressed bladder. She glares with even more venom than usual at the man relieving himself unconcernedly behind the bus stop. Scene 2: Gingerly she steps in, pushing the dirty latchless door shut with her foot. Noting that as usual there are no hooks, she hangs her bag around her neck. Then lifting her clothes awkwardly around its bulk she squats, carefully ensuring that no part of her body touches the sides of the wall. As she relieves her bursting bladder, she reminds herself to be grateful that there is a loo at all, whatever its state. If we had to pick one tangible symbol of male privilege in the city, the winner hands-down would be the Public Toilet. Any woman who has lived in Mumbai will testify that the number of public toilets in the city is grossly inadequate. On many streets one comes across little white-tiled box-like structures that are men’s urinals without any sign of similar arrangements for women. Those toilets that do exist are often in such a bad state that women wish they didn’t have to use them. In any case, these existing toilets only serve to underscore the inequities in provision. Usually just one-third is occupied by the women’s toilet; the remaining two-thirds house the men’s urinals and the men’s toilets. The toilets shut at night while the urinals usually remain open round the clock. Furthermore, the urinals are free but the toilets are usually of the pay-and-use kind.26 There is a completely unembarrassed air about this disparity. For instance, a notice at the Bandra suburban railway station reads: ‘Men’s toilets: 2, Women’s toilets: 2, Men’s urinals: 24’. These figures seem all the more lopsided and insensitive when we consider the fact that women need more time than men to urinate, and need to use toilets more often. To actually provide equally for women and men, we would need at least twice as many toilets for women as for men.27 Railway stations are among the few places where there are toilets for women. However, we found that some of the women’s toilets were actually being used by men, while others were locked or difficult to locate. For instance, in 2004, when we studied the Andheri station, it had four functional toilets. The first toilet on Platform 1 was for both women and men and was open from 6 a.m. to midnight with female attendants managing the women’s section and male attendants in the men’s section. The second toilet, also on Platform 1, only had urinals for men, open all twenty-four hours. The third toilet on Platform 2 had facilities for both women and men, but the men’s urinal was open and the women’s toilet was locked. We were told that the local shoe polishwalla on the same platform had the key. There was no notice, however, to this effect nor was the shoe polishwalla to be found on that day. The fourth toilet on Platform 5 was open from 6 a.m. to 10 p.m. The women’s section was locked with an almost illegible note scribbled on the door which read: ‘Ladies shauchalaya chaloo hein. Ek rupya dekar chaabi gents’ shauchalaya se lijiye’ (The ladies’ toilet is functional. Pay one rupee and get the key from the men’s toilet). Though we hung around the men’s toilet looking for the attendant, we did not find him. In sum, for men, there were four possible toilets that they could use in different locations; for women, only one. Many women interviewed at the station did not know where any of the toilets were located.28 Elsewhere in the city as well, the toilets that do exist and are open, are far from clean. Many middle-class women we talked to over the course of our research said that they had never seen the inside of a Sulabh Shauchalaya.29 The public toilets they had used, if at all, were either ones in coffee shops, theatres or art galleries. When caught in desperate need, many a middle-class woman would rather pretend her way into the nearest five-star hotel’s private toilet rather than use the Sulabh toilet right across the street. Of course, lowerclass women do not enjoy that privilege and are forced to make do with whatever minimal facilities they can find. For the working-class woman, the lack of toilets is an everyday reminder of her unwantedness in the city. For women residing in slums, for instance, toilets are often a great source of anxiety.30 These women speak of waiting for the cover of darkness in order to relieve themselves on the open street; often not drinking fluids during the day so as to avoid the nuisance of trying to find a toilet they could use. Even when there are public community toilets, they are not always safe, particularly at night when the dimly lit streets and dark cubicles can seem forbidding. Women then make sure they go in groups for company along the way and to keep watch. It is not surprising then that for women in Dharavi, one of Mumbai’s largest slum settlements, a private toilet comes right at the top of their wish list.31 What makes the disparity in the provision of public toilets even more outrageous is the fact that this scarcity has direct implications on the everyday health of city women. Most of us will consciously drink less water when outside the home and as we grow older, learn extreme forms of bladder control that can sometimes lead to serious urinary tract infections. If public toilets were to be your guide to imagining the city, what would they say about Mumbai? First, they would imply that there are very few women in public as compared to men: for if the average ratio of toilet seats for women and men in most public toilets blocks is anything to go by, there is just one woman for every five men out there. Second, they would suggest that if Mumbai women do need to pee, they do so at home or in their school/college/office toilets rather than use a public facility. And third, they would say, since even fewer facilities are open after 9 p.m., respectable women have no business being out in public after dark. The disparity in the provision of public facilities is often justified in terms of the disproportionate usage of public space by women relative to men. While it may be true that there are fewer women in public than men, it is assumed that this will always be the case. These assumptions also seem to miss the point that not only have there always been a large number of women in Mumbai commuting and working outside the home, but that these numbers have only increased. However, the lack of public toilets for women cannot be seen in isolation as just a matter of oversight by town planners or a simple lack of attention to their rising numbers in public. It reflects underlying notions of purity and pollution, particularly those connected to the female body. In India, a hierarchical Hindu social order structured around stringent rules of cleanliness and dirt— exemplified in the caste system—permeates society at large. Excretory functions of the body are high in this order of pollution and until recently, in some parts of the country, having a toilet inside the house was considered sacrilegious. Even today, municipal employees who work in the lowest levels of the sanitation department continue to be from the scheduled castes as others are reluctant to do this job. Since both women and toilets are seen as contaminating in relation to public space, a language of shame pervades any discussion of toilets for women. This adversely affects the actual provision of toilets for them. Any discussion of women’s bodily functions is immediately seen as linked to their sexuality and hence to be silenced. Women’s bodies are associated with bodily secretions—menstruation, ovulation, lactation—seen as sources of ritual contamination at particular times of the month or year. These notions of contamination are so much part of women’s conditioning that women reported during our workshops that they were usually too embarrassed to even ask for directions to a toilet. As one woman told us, ‘I would never be able to ask for a toilet when there are men around, I either make some other excuse or just hold it.’ As if the lack of adequate numbers of toilets in the city was not enough, the designs of toilets that do exist also fail to provide for the specific needs of women. In general, architects and planners have an aversion to dwelling too much on the design of toilets (unless they are super-luxury private bathrooms). This mindset is a reflection of larger cultural attitudes where toilets are objects of shame, mockery and sometimes, revulsion. This aversion to the essential ‘toiletness’ of toilets is so high that great efforts and monies are spent on disguising public toilets to look like anything but toilets. So the public toilet at the Gateway of India was made to look like a miniature, illproportioned Gateway, and the public facility near Churchgate railway station is so camouflaged by plants that many daily commuters are unaware that it is a toilet, defeating the very purpose of its existence. Public toilets for women, particularly, appear to have been designed rather absent-mindedly. For example, at the time of our research in 2005, in the aforementioned plant-camouflaged toilet outside Churchgate station, the area provided for women was less than one-fifth of the area provided for men.32 While the men’s section had six toilet seats, two baths and fifteen urinals, the women’s section had only three toilet seats, period. As compared to the spacious men’s section, the open area in the women’s section comprised a narrow corridor. This is not just uncomfortable and unhygienic, it also leaves no space for other functions women might need a public toilet for, such as checking, adjusting or changing their clothing. There was absolutely no provision for women with children, such as diaper-changing tables or child seats. Moreover, the design of the toilet also created a sense of discomfort for women by providing a window between the men’s and women’s sections. The way women use toilets for urinating is different from the way men use them, but this is never taken into consideration.33 A pervasive problem women face in public toilets is the absence of hooks for purses or bags in the WC cubicles. Women usually carry their essential belongings in their bags and not in pockets like men do. So, without a dry place to keep their bags, they often find themselves forced to use the toilet in awkward positions. Given the gymnastics they have to perform because of bad design, it is not surprising that most women say they use public toilets ‘only in an emergency’. If public toilets in Mumbai suggest that women in general are not welcome in public space, they also seem to imply that menstruating, pregnant and lactating women simply do not exist. If discussing the need to urinate is embarrassing for women, then menstruation is completely taboo. In fact, advertising for sanitary towels underscores this lack of facilities as they set out to impress you with how long you can use their product before you simply have to change.34 For pregnant women, the lack of toilets at a time when bladder control is near impossible makes being out in public an unpleasant adventure. Women with young children have to further contend with the unfriendliness of the city’s public spaces (streets, railway stations, parks) and semi-public spaces (restaurants, malls, department stores) towards providing the most basic childcare amenities— mainly a comfortable place to breastfeed, a clean spot to change the baby’s soiled nappy, a toilet seat sized for a child’s bottom, and lowlevel wash basins positioned at a child’s height. Where facilities are provided, they are tucked away only in the women’s toilet, assuming that mothers carry the sole responsibility of childcare. All this then further restricts the mobility of women with young children.35 Lack of sensitivity in designing public toilets results in not just physical inconvenience to the users but also conveys a sense of disrespect towards them. For women, in particular, social structures already dictate that their bodily functions are shameful and unworthy of public discussion. Inconsiderate toilet design underlines this notion, making women’s access to public space even more fraught with anxiety. What the lack of public toilets says is that women are less equal citizens than men and don’t deserve the same consideration. At a time when the design of urban spaces has come to the forefront in civic debates, the design community as well as policymakers will have to accept that toilets are an integral part of our landscape and make toilets more user-friendly and hygienic, rather than try to wish them away.36 It is equally critical to address the gendered social, cultural and functional aspects of public toilets openly instead of skirting the issue in embarrassment or ignoring it because of its apparent banality. The provision of more public toilets for women and other marginal groups, the disabled and children among them, is an important statement of the recognition that they belong and have rights as citizens. The provision of adequate and sensitively designed public toilets has significance beyond questions of infrastructure; it has implications for the ways in which people perceive themselves and envision a politics of citizenship and belonging. 11. Playing If there one thing that infuriates us, it is the appalling lack of any public recreational space for women in the city. Sometimes, it is simply the improbability of finding a bench in a park. First, you need to find the elusive park, then the rapidly disappearing bench, and having found your little haven in the city, you need to contend with the real challenge: dealing with being stared at, commented upon and generally made to feel uncomfortable, especially if you are alone. If women can do it in Central Park in New York, Hyde Park in London or even Lumbini Park in Bangkok, why can’t we do it in our own city? Why is there no place for a woman to go to alone, and just hang out, peacefully read a book, look at the trees and flowers, stroll around or merely sit on a bench and watch the world go by? Of course, in Mumbai, you might argue, it is unfair for women to ask for space when there is hardly any public recreational space even for others. And whatever little there is, is fast shrinking. Many middle-class people in their thirties and forties remember idyllic weekends as children spent at Juhu or Girgaum chowpatty, the Rani Baug zoo, Hanging Gardens, or the local park down the lane.37 These were places our parents took us to when we were young and which we then frequented with cousins and friends as we got older. Yet today, when those of us with children think of places to take our children to, these are not the places that we choose to go to. The chowpatties and Hanging Gardens are visited only when out-of-town guests insist on seeing their image of Mumbai.38 Family weekends for many now means hanging out at the malls or meeting friends at coffee shops. Parks and promenades are the most visible public spaces in the city and the city’s attitude to them reflects its attitude towards its citizens. The ratio of open space per thousand residents in globally aspirational Mumbai is a shameful 0.03 acres as against more than three acres in New Delhi and Kolkata. The National Commission on Urbanization (1988) suggests that the ideal ratio of open spaces is 4 acres per 1,000 persons.39 The receding public spaces in Mumbai are a result of multiple causes which include, among others, a warped vision for the city, poor planning, conservative ideas about morality and control, and the increased ‘privatization’ of public spaces. Open spaces do not even figure at the policy level in Mumbai. In fact, open plots with public access are de-reserved regularly to be replaced by privately owned facilities. Even when the mill lands in Central Mumbai became available for redevelopment, the possibility for the city to have one large open park, accessible to all, and/or several smaller parks, was lost because of vested real estate interests and the lack of a comprehensive vision for open spaces in the city.40 Where open public spaces do exist, they often tend to be badly maintained or policed stringently—both discouraging popular use. Most of them are not equally welcoming to all and are often governed by an impulse not to include, but to exclude. Open spaces like parks are frequently seen as an invitation for what is termed as ‘anti-social-activity’.41 The assumption is that if open public spaces are provided, then people—that is, those-who-do-not-really-belongto-the-city—will somehow misuse them.42 Meanwhile, as we have discussed in the chapter ‘Unbelongers’, the numbers of those-who- do-not-really-belong-to-the-city keeps on increasing. If it was once largely the vandal who was to be barred in public space, today, it also includes among others, the hawker. This social segregation and exclusion is reflected in the everyday spatial practices of the city. Cases in point are the new concepts of public space management that have emerged in the last decade or so such as paid parks and the participation of local residents’ groups in the upkeep of public spaces.43 While on the one hand these have aesthetically improved the spaces under their jurisdiction, on the other hand, they sometimes work with an implicit agenda of keeping out those perceived as ‘undesirables’ from public space. The concept of the ‘paid park’ was introduced in Mumbai in the 1990s.44 The apparent idea behind such a park is to charge a nominal fee from users so that a) they have a sense of responsibility when using the space and b) the money collected can be used for the park’s upkeep. However, as our ethnographic research in two such parks of the city revealed, the entrance fee does far more than that. Setting a fee for accessing a public space fundamentally militates against the principle of open public space. ‘Paid parks attract wellmannered, upper-class people,’ said an eighteen-year-old girl who regularly jogs and socializes at Joggers Park in Bandra. ‘Since lower-class people cannot afford the daily fee, they come only on weekends. This filters the crowd here to a large extent all week long.’ However small it may seem, a fee has the effect of fundamentally segregating the space on the basis of class. In City Park at the Bandra-Kurla Complex, for example, the entry fee of Rs 10 for every person over the age of three may not be much for middle-class people from nearby neighbourhoods who regularly use the jogging paths for walking and running while their children use the park’s skating rink for private roller-skating coaching. Those, on the other hand, who cannot afford to pay the entry fee every day —if they happen to be men, hang around outside the park, and if they are women, wait for weekends and public holidays. These are the special days when families from nearby slums in Dharavi, Bharat Nagar and Behrampada come there. Ironically, our interviews show that on these days the presence of working-class people, and particularly Muslims, marks the space as undesirable for middleclass, local residents, especially women.45 One young woman said she would rather take her children to the mall on holidays when the park is full of ‘those people’. In an attempt to control local open spaces, manage them, and make them available for local use, residents’ associations have sprung up all over the city. At face value, these are democratic organizations widely held up as an example of public participation in governance. Unfortunately, they end up representing just the middleclasses, and not all citizens who use these open spaces. Amongst the most visible projects of residents’ associations in the city is the upgradation of the long stretches of sea front in Bandra—the Carter Road and Bandra Bandstand promenades.46 The promenades have been paved, fenced, beautified and new facilities such as amphitheatres, small parks and children’s playground equipment have been added to them. Besides walking and sunset gazing, new ways of using the promenade have emerged such as tai chi classes on Thursday mornings, weekend art classes, late evening music concerts, plays and poetry readings. While these have expanded access for some people, the promenades are now also stringently policed, especially against vagrants, hawkers and couples. One fiftyseven-year-old housewife who regularly uses the Bandstand promenade feels that this policing has a purpose. ‘It is not to do with safety but the kachara (dirt). If there are bhelwallahs, people will eat on the promenade and then throw trash. Then the dogs and crows will spread those thrown packets. It is quite a pain. You can’t enjoy your walk. We want people here who can understand the value of public property.’ Certainly, the residents’ associations here have salvaged these areas from decay and done a more than competent job in keeping them shipshape. The problem is that in doing so they have overstepped their rights and also attempted to erase the presence of several groups of people—among them the poor, the roadside vendor, beggars, couples, cyclists, people with dogs, and so on. Some, like the dog lovers of Carter Road, for example, have fought many pitched battles with the residents’ association to allow their dogs on the promenade. Eventually, they have managed to get a green patch on the promenade reserved for dogs, close to the park reserved for children.47 But other non-middle-class groups haven’t found it easy to petition for their rights to the promenades, which incidentally, are on free public land, for work or play. Parks as open public spaces are also used to impose a specific ‘moral vision’ of order on the city. The response to the presence of ‘anti-social activity’ or vagrant ‘elements’ has been to either not have parks at all or to turn them into spaces which are watched and policed in order to keep them beautiful. Citizens’ groups would like parks to comply with notions of middle-class aesthetics and morality. Timings for opening and closing, rules about edibles, lists of dos and don’ts in the park, and the presence of visible security signify not just concerns of beauty and cleanliness, but also of morality. In Mumbai, as in many cities across the country, this morality is peculiarly directed at public displays of romantic affection, and sometimes, even the mere presence of couples. In a city where the private home is often a space of crowding, couples seek privacy along the promenades or in parks across the city. In some ways, the public offers them an anonymous sanctuary. But not for too long. Increasingly, in city public spaces, couples are being censured for holding hands, and ostensibly threatening the ‘moral fabric of Indian society’. At various times, police personnel have been directed to discourage couples from public displays of affection by shooing them away or even arresting them. In fact, this so-called ‘moral’ policing is also imprinted on the body of the city through the design of public space infrastructure such as park and promenade benches with dividing armrests and singleton seats. For instance, in Joggers Park, there are individual seats set in singles, twos and threes, but no benches. The manager of the park explicitly stated that this was to prevent couples from ‘misbehaving’.48 Similarly, some years ago, in the Five Gardens area of Dadar, park benches were made into single-seaters by the local municipal corporator to discourage couples from engaging in what he termed as ‘indecent behaviour’.49 The latest attempt to ‘moral’ police was the plan to install CCTVs in private housing societies along the Bandra Bandstand seafront to record the so-called ‘indecent behaviour’ of people on the promenade. The footage was to be monitored by private individuals belonging to a local resident’s association that initiated the idea. Luckily a media outcry that highlighted the brazen flouting of privacy norms and the grave potential to misuse the recorded footage, put a stop to the move.50 The Mumbai police have periodically targeted courting couples in the city on grounds of obscenity and/or immorality. In November 2004, the police arrested forty-three couples on the promenade at Bandra Reclamation for ‘indecent behaviour’. In April 2007, the police fined at least eighty persons in a drive against ‘indecent behaviour’ in the same area. In the present, such moral policing is aimed at heterosexual couples, but this is reflective of the invisibility of same-sex couples rather than any progressive politics. In fact, the situation as such is worse for those expressing alternative sexualities. If heterosexual couples find it difficult to find undisturbed spaces, for same-sex couples, it is virtually impossible. Women are often the prime targets in cases of culture policing. When canoodling couples in Mumbai’s public spaces are rounded up and taken to police stations, it is often young women who are sought to be shamed by threats of informing their parents. For example, in the Marine Drive rape case in 2005, a private security guard appointed by the local residents’ association complained to a policeman about the young woman and her male friend who were hanging out on the open public promenade in the late afternoon. The policeman on duty took the couple for questioning to the local police chowki, threw the boy out, and then proceeded to rape the girl. Her ‘crime’ apparently was being out with a boy in a public place even in broad daylight. Certainly, the Marine Drive rape case is an extreme example. But it is no less true that on an everyday basis, women in public are policed on where they are hanging out, what they are wearing, who they are with or without, what time they are out and so on. When being in a public park or promenade poses a potential threat not just to their physical safety but also to their respectability, women often respond by avoiding these spaces. The intent of inclusiveness in a public open space is both reflected in its design and determined by it; the material design of these spaces plays a significant role in deciding who feels safe and comfortable using them. Simple elements like lighting, fencing, benches, and vegetation go a long way in encouraging or discouraging people from using them.51 Unfortunately, the recent restoration and ‘beautification’ of some parks and maidans in the city have failed to make these spaces more welcoming. This exclusion goes hand in hand with the gentrification of public spaces such as in the case of the Oval Maidan. Citing reasons of ‘anti-social’ activities and neglect, the Oval Maidan, located along one of the busiest pedestrian corridors in South Mumbai, was taken over and restored in the late 1990s though the initiative of a local citizens’ group.52 The project was successful in aestheticizing the space, cleaning up the over-growth, keeping well-maintained grounds and adding a beautiful high fence, a cobbled walkway, and carefully chosen light posts. Yet, the new Oval fails to engage with the city in any manner that would befit its scale and location. The design of the Oval Maidan now clearly demarcates it as a space for people with ‘a serious intent of park usage’. This mostly includes the cricketers who occupy the north segment of the maidan, and the joggers—many of whom live in the adjacent buildings. While there are people, mostly men, who hang out on the lawns, both the largeness of the space and the fact that it does not actively provide for the ‘hang-outers’ (there are no benches in the Oval) suggests that they are definitely not encouraged and, if at all, have a limited claim to the space. The maidan is policed more stringently and closed at night with the intention of keeping out ‘anti-social’ elements.53 Informed by this fear, the project succeeds in its intention, but also manages to keep out many others, including women. A singular design feature determining this is its edge—the high iron grills that restrict the movement across the maidan—separating, rather than connecting it to the city. Many respondents in our study of the park report that they do not always feel comfortable using the space. ‘What is the use of a park with closed walls? It should be open space. High fencing of the Oval prevents me from walking through it,’ said one middle-aged person who regularly walked from Churchgate to Backbay Reclamation along the Oval Maidan footpath. Because of the high fencing and a single thoroughfare across its shorter side, deep north and south corners are formed in the maidan. As a result, although there is a visual connection (the possibility of seeing and being seen) that will discourage assault, there is low possibility of escape if such an assault does happen. The lighting in the Oval Maidan, particularly on its southern end, is also found wanting. Such a situation is a classic case that discourages women from accessing the maidan unless in groups or with male company. What could have become a hub of activity in the city has been sanitized and limited to the use of a few.54 In contrast, Shivaji Park—the only large maidan in Central Mumbai —is a very good example of inclusiveness. The maidan supports activities ranging from intimate conversations of couples to political rallies attended by tens of thousands. Mothers chat on its edges or take a brisk walk while they wait for their children (there is a school across the maidan), old people meet in informal clubs or visit the nana-nani park located in one corner of the maidan, young boys earnestly train in their cricket gear (the maidan is known for the number of prominent national cricketers who have played here) and young women bunking college often make a detour to the temple there. The shifting activities in and around the maidan begin before daybreak and carry on late into the night. It is not as though Shivaji Park is equally accessible to all. When it comes to playing in the maidan, other than the occasional women practising the malkhamb, it is boys and young men who far outnumber the women. Most of the time, they are found playing cricket in the centre. Some older people and women have expressed anxieties about being hurt during these games in our interviews. Yet, very few of these anxieties relate to the physical design of the maidan. Although the maidan is located in the middle of a predominantly upper-caste Maharashtrian residential locality, its openness gives it the sense of belonging to the larger city. The low edge wall or katta merely acts to demarcate the maidan from the space around it without fully restricting access at any point. Both the wall and the pavement running outside it are wide enough to allow enough space for both serious walkers and random social encounters. The large trees along the edge provide shade without blocking vision into and from the maidan. Both the vastness of the space and the accessibility it offers suggests that it is intended for multiple activities and people. Moreover, the fact that the maidan is open at all times of the day and night (it is one of the few public recreational spaces in the city which does not—cannot be—closed at night), means that it is active until quite late in the night. This is another factor that makes women feel safe in and around it. Shivaji Park, however, is a rare exception. In general, the public open spaces in Mumbai are designed to discourage ‘vagrants’, particularly those of the lower class, unemployed male variety, from accessing them legitimately. The overt intent behind this impulse is the protection of respectable citizens (particularly women) from those who are seen as a source of danger—prostitutes, beggars, unemployed youth, drug users and increasingly, homosexual people. The desire to police is also justified by the fear of vandalism. Yet, paradoxically, in setting up a variety of physical barricades against these ‘anti-social elements’, it is women who are discouraged from using these public spaces. Urban designers and planners have repeatedly pointed out that the way to make a public space safer is not by keeping out the ‘undesirables’ but by encouraging more and more ‘desirables’.55 The irony of the matter is that in Mumbai, far more energy is spent on keeping out people than in inviting them in. This situation that can only be maintained through relentless policing as it is premised on the exclusion of the majority who might be impoverished, overwhelmingly numerous or visually unappealing. It is for this reason that an access fundamentally dependent on surveillance eventually remains limited. The design of public facilities determined by an exclusionary impulse actually makes these spaces inaccessible and sometimes even unsafe for women. The increasing sanitization of open public spaces in the name of beautification has its devoted fans, particularly among the middle classes. Middle-class citizens’ participation in transforming these spaces reinforces their sense of entitlement on the city. Ironically, the more middle-class citizens assert their citizenship, the less these spaces are available for ‘those others’ who can ill-afford to buy access into private spaces of recreation. What we would like then are open spaces that are not maintained through the tenuous and contested division of people into ‘us’ and ‘them’, desirable and undesirable. What we want are open public spaces in the city that are welcoming to all manner of people and remain so because they evoke in them a sense of belonging and responsibility, and underline their undifferentiated claim to the city. 12. Designed City In an exercise we conducted in architecture colleges, students were asked to trace the path they would choose while negotiating a fictitious street. The street is edged on one side by a park; its adjacent footpath neatly fenced on both sides and lined with trees. It is the kind of textbook-perfect edge urban designers dream of creating. On the other side of this hypothetical street is lower-middleclass housing—with household activities spilling out unevenly onto the street—the nightmare of city planners. Ironically, an overwhelming majority of the female students who took the exercise concurred that they would choose to walk on the residential edge, despite its messiness, because it appears friendlier and safer. A tree-lined fenced footpath with low visibility, they argue, would make escape difficult in case they were harassed. Besides, given that it is primarily men who are socially sanctioned to ‘hang out’ at public places, parks are often predominantly ‘male spaces’. So, even those who choose to walk on the park edge prefer to do so along the road rather than within the fenced-in footpath, lest they be heckled. As women, it is clear that they prefer to walk on the more ‘chaotic’ edge of the street. Our question then is as architects or urban planners, which edge would they design? And there is silence—the beautiful silence of irony hitting home. The moral of this story is that architects, as well as other design experts or spatial technicians, very often design in and for an imaginary context that is determined by aesthetic values where concerns such as safety and comfort are not only secondary, but sometimes even irrelevant to the process of design. Usually, material environments in cities—which range in scale from large buildings to details such as fencing, paved footpaths, benches, lighting—are just considered a backdrop against which social drama is played out, or at best, a reflection of society as it is. The proactive role of the built environment in producing social experience is rarely acknowledged.56 When it comes to the affective sense of safety or comfort in a particular space then, it is most often defined in terms of the people who occupy the space rather than a product of the particular attributes of the space itself. However, as much of our research has shown, this is far from true. The students at our course in the architecture college did an assignment that we titled ‘Safe/Unsafe Spaces’, where they were asked to identify two spaces from their everyday experiences, one which they would define as safe and the other as unsafe, and to map these spaces through drawings, paying particular attention to the physical/material aspects of the space.57 Students realized that in spaces they used regularly, they sometimes subconsciously chose to take detours which were many times longer—and more cumbersome than the most convenient route from one point to another just because the shorter route was not comfortable. And much of this had to do with how the space was constructed in terms of its enclosure, visibility, light and scale. In general, spaces without visual connection (where you could not look at or be looked at by others outside the space), narrow enclosed spaces which did not allow escape in case you were accosted, and spaces with poor lighting were found to cause the most anxiety amongst women users and created a sense of unsafeness and discomfort. These street experiences that generate feelings of safety and comfort make a huge impact on women’s everyday relationship to public space and the role of the material aspects in facilitating or impeding this experience cannot be underestimated. When it comes to women and public space, the answer to the sceptical question ‘Can design really change society?’ must be a qualified ‘Yes’. While ‘bad design’ of public spaces might not directly cause verbal or sexual assault, the inverse does hold true. Design can go a long way to make a space inviting to women and discourage situations where women get harassed. Similarly, while design by itself might not be able to create an equitable and welcoming public space for women, it can create the situation for change to happen and reinforce it when it does.58 As often happens, business practices have been quick to realize the crucial role of design to the desirability of spaces. In a context referred to earlier, when the two prominent coffee shops in a hip Mumbai suburb were sought to be closed down, alleging that they were used as places to solicit by women sex workers, one of these coffee shops issued a statement stating that the design and ambience of its space was such that it actively discouraged ‘sleaziness’. The statement read: ‘[as a] friendly neighbourhood café … Our outlets are brightly lit and are designed with transparent glass walled entrances to provide a sense of openness and security to our guests. The ambience is far from being sleazy.’59 This claim is unanimously supported by their customers. Many middle-class women say that they feel comfortable in these spaces —in that here they could wait for a friend or have a solitary mug of coffee (though usually accompanied by a book or a magazine). This is borne out in an exercise called ‘Putting People in Place’ that we conduct during our workshops, where participants are asked to locate a variety of people in an ambiguously tagged neighbourhood ‘tea shop’.60 Whether participants locate women in this ‘tea shop’ or not depends on what they imagine it to be. Those who imagine it to be a roadside cutting-chai stall never locate women inside it; those who perceive it to be an Irani café conditionally locate some women inside it; but an overwhelming number of those who imagine this to be an upmarket coffee shop unhesitatingly place women inside it. The reasons for this are obvious. First, there is a class restriction on who can be in the coffee shop. The bright lighting invokes the respectability of the day (even at night, which contrasts with discos that are dark even during afternoon jam sessions), which combined with the innocuousness of coffee (as compared to alcohol) creates a space that presents itself as unthreatening. Coffee shops are respectable then in a way that bars or lounges might not be. The expansive use of glass in the design of these spaces contributes significantly to this sense of comfort. Glass creates an illusion of publicness—even as the lighting inside creates a sense of both transparency and intimacy. It creates not just the illusion of access, it also offers up the assumption of transparency: the illusion that whatever happens inside is an open book. The use of glass as the defining feature ironically renders the space of the coffee shop, simultaneously both, public enough and private enough to be respectable. Glass, used here to lure certain customers, particularly respectable women, also works as an effective barrier—its very brazen openness working to keep away the undesirables, particularly the lower classes. Sometimes, the inhibiting presence of the glass barrier extends to the space immediately outside it as well. In many of these coffee shops, the seating spills outside the glass barrier. However, though one sees poor people and sometimes beggars on the footpaths outside, there is an invisible line that demarcates these class-defined spaces that they do not breach. Mall design is similarly characterized by the use of glitzy transparent barriers that both invite some people and keep out others. Malls, in addition, also have security guards whose very intimidating presence regulates the kind of people who feel able to enter such spaces. These spaces also mimic each other in design, creating a sense of familiarity—once one is acculturated into the codes of one mall, it is not very difficult to navigate another. They generate a sense of familiarity that is both circumscribing and reassuring at the same time. No wonder then that many middle-class women we interviewed referred to the mall as a ‘public’ space where they frequently hung out. However, as discussed earlier in the chapter ‘Consuming Femininity’, keeping out those deemed threatening does not take away the pressure on women to reproduce the structures of both femininity and middle-class respectability in these new spaces of consumption.61 One key obstacle in the good design of public spaces is the assumption of a neutral universal user of space. More often than not, particularly in the absence of a unique client as is the case for urbanscale projects, designers and planners assume a generic user of the space. Unsurprisingly, as we have argued before, this ‘neutral’ user is usually male.62 However, different bodies have different needs and experience the same space differently, depending on their gender, class, age, sexuality and physical ability. These different identities not only determine how you sense the space, but they decide whether or not you can access a space in the first place. By treating men as generic human subjects and all others as specialized sub-groups of this norm, design often tends to fundamentally discriminate against a majority of its users. The exemplification of difference-blind design is the public toilet discussed in the chapter ‘Peeing’. The question that feminist architects and designers constantly face is: will we be accepting and perpetuating difference if we design differently for women? In other words, can one design for safety without accommodating, and, therefore, accepting the conditions that create discrimination in the first place? And then, it is really possible to design in a way that is sensitive to everybody—won’t some group or the other always be left out? It’s a valid question. It may never be possible to always cater to everybody, but perhaps, if we stop designing in a way that consciously excludes certain people, chances are that it will make the space more inclusive. Making the city safe for older women would make the city safe and accessible for others too. For instance, better street lighting, lower bus steps, paved sidewalks, broad, unchipped steps on foot-over bridges and usable public toilets would not just benefit children, the physically challenged and women, but also all men. Moreover, referring to our understanding of ‘formal equality’ versus ‘substantive equality’, one needs to also see difference-sensitive design as a provisional step aimed at bridging the gap between theoretical and actual equality. This requires minimal monetary investment and importantly, a commitment to making spaces more accessible through intent and design. Design in urban public spaces is not just relevant at the micro level to individual parks and toilets, but also at the macro level to the overall planning of the city. Over the past few years, Mumbai has been steadily undergoing a makeover into the global image of streamlined order: gleaming steel and glass skyscrapers, airconditioned office spaces, flyovers for snazzy cars, and prepackaged recreation. These developments are constructing a new geography of the city where streets are conduits for speedy movement, neighbourhoods become gated communities of contained order and public spaces merely lost opportunities for more development. This short-sighted, bottomline-focused thinking is slowly making the city into a cluster of islands of sanitized exclusivity. In this situation, public space is reduced to leftover space, its value limited to connecting private spaces or enhancing their value. As people feel decreasing claim over public space, increasing policing is required to maintain it. The primary strategy for achieving this image of the global city is that of segregating spaces for different people and activities. All diversity is attempted to be contained into a singular image of the built form, exemplified by vertical towers. Defining urbanity in this one-dimensional manner ignores the inherent plurality of the city as reflected in its diverse built environment.63 In the last few years, moreover, critical policy decisions and amendments in development regulations have sought to erase the existing urban fabric and drastically reduce the quality and quantity of public space.64 This tunnel vision of the city is unfriendly to women at multiple levels. For one, zoning spaces on the basis of use into residential and commercial areas is detrimental to women’s mobility. Our research shows that women have more access to public space in mixed-use areas, where shops and business establishments are open late into the night, ensuring activity at all times. Second, vertical development often means a detachment from the ground. In comparison to low-rise horizontal urban forms, the public spaces of a vertical city are less friendly and safe, particularly for women.65 And third, when public space falls off the agenda in planning, what is left becomes increasing privatized, policed and often fraught with risk. Contrary to common sense notions of urban ‘beautification’, clean lines and peopleless streets do not equal comfort or safety for women who often seem to prefer a degree of chaos, ambiguity and multiplicity to univalent notions of cleanliness and order.66 The first impulse of design based on ‘rational’ modernist principles— as is prevalent even today—is to reign in chaos and enforce a visually clean order on the lived messiness of the city. Flexibility and creativity in the use of public space that is a departure from its apparent intended use—an absolute bane of planning professionals —is actually a mark of its success.67 Unfortunately, designers see the everyday spatial negotiations of people in the city as mundane impediments in the path of pure design, instead of being its very purpose. What is needed then, is not a call to sacrifice aesthetics at the pragmatic altar of safety and accessibility, but a new aesthetics of inclusiveness, where right of access of all defines what is good design and what is not. In Search of Pleasure 13. Who’s Having Fun? For many in India, the term ‘Bombay Girl’ is evocative of a kind of gendered modernity and liberation that is simultaneously envied and derided. The ubiquitous image of the Mumbai woman is often that of the bindaas Bombay Girl. She is imagined to be the one living it up— early mornings, long afternoons and late nights—cocking a snook at those forced-to-stay-at-home Delhiwallis, too-timid-to-move Chennai babes, and not-so-many-places-to-go-to Kolkata dames. Some might imagine her late on a Friday night, dozing on the local train bound for Kandivali, returning from a raucous office party. At dawn, she is practising tai chi at Carter Road or stretching her limbs in yogic asanas at Shivaji Park. On a pleasant evening, she romances her boyfriend on the Marine Drive tetrapods or hangs out with girlfriends, checking out the latest fashion at King Circle’s Gandhi Market. Some nights, she grabs a drink at a Colaba pub; on others, she indulges in a spot of belly dancing at a dance studio in Sion. She is apparently having all the fun and making few attempts to hide it. Like all other myths, this imagined woman is part-fantasy, partfiction, part-reality. Many Mumbai women may live this imagined life in ephemeral fragments. The air-brushed image, however, inevitably conceals all the backstage strategizing that props up every fleeting moment of pleasure. Mumbai is a city where it may seem possible, if not always comfortable or easy, for women to be out late and alone, and even use public transport to go home from work or a night of partying. It is partly because the city does allow access and partly because women are very creative at accessing public space without appearing to transgress any boundaries, so much so that one can often forget how fragile this access actually is. We are reminded of this whenever there are attacks on women in public space. These incidents, ironically, never lead to a demand to enhance women’s access to public space, but rather to calls upon women to be more careful and not take unnecessary risks. The definition of what constitutes an unnecessary risk is also ambiguous. Standing at Churchgate railway station at 11 p.m. waiting to take the train home may be classified as a necessity, while hanging out on Marine Drive less than a kilometre away is likely to be categorized as excessive. The fundamental reality is that women who demonstrate respectable purpose have socially acceptable access to public space. Although the abstract Lakshman rekhas or boundary lines differentiating essential from avoidable ventures into public space can never be erased, they can be pushed, bent and twisted, depending on the woman’s geographical location, class, caste and community position, and individual familial situation. In this book so far, we have explored the nature of women’s basic access to public space in the city. In this section, we push the idea further to ask if women can also access public space for so-called non-productive reasons—to have some fun and loiter in the city. Keeping in mind that the Bombay Girl is far from being a singular entity, we query whether fun means the same thing to all women or if there are different desires and limits that define different women’s engagement with the city. We ask how different women seek to fulfil these desires and the intricate masquerades they are forced to enact along the way. And then we ask what their actions might mean not just to themselves but also to other women and to the city of Mumbai. Women’s tactical skills at playing with various disciplining boundaries are really tested when they want to access public space not for any ‘necessary’ purpose but just to have some fun. And every woman manipulates these boundaries differently as she negotiates different parts of the city and inhabits different aspects of her own life. In Bandra, for example, one can be a good girl in a short skirt while in Matunga, good girls show no leg. Though, of course, a Bandra girl in Matunga might be excused—for as an outsider, the rules don’t apply in quite the same way. In Malabar Hill, the virtuous married woman might wear a short skirt in the company of her husband but she must hope that her grandmother-in-law won’t see her as she slips out of the house. In Hiranandani, Powai, the night club is a five-minute walk away and the short skirt is cool so long as she doesn’t plan to leave the safety of the gated enclosure. In Chembur, if one is going to a night club in a private car, a short skirt is acceptable, even desirable, while good Mulund girls can wear the short skirt but not in Mulund, please. The short skirt, of course, is a parody, and the descriptions based on local stereotypes, but the mental gymnastics that women perform when thinking about what to wear, where and when, are no less convoluted, and certainly much less amusing. Being Bombay Girls means understanding the various unspoken codes of dress and conduct and acting in accordance so that you can play the good girl and still have fun. This involves elaborate strategizing to access public space while simultaneously ensuring that you retain your reputation as a good girl. These tongue-in-cheek connections with regard to the codes in different localities are based on the stereotypical ways in which different areas in the city are seen. The shifting geographical boundaries of perceived safety are linked inextricably to the assumed class profile of the locality. For instance, there is a popular perception among people that middle-or upper-class localities are safer for women. Interestingly, in our research, we found no evidence to suggest that this is true. Furthermore, all localities in the city are mixed by class even though they may be seen as predominantly being one or the other class. So for instance, though Malabar Hill has slum settlements and some chawls as well, it is nonetheless classified as an upper-class locality. So also with Mulund and Chembur, both marked as middle-class suburbs that have their share of not just slums, but very upper-class enclaves as well. Dharavi, despite its mix of communities and varied income levels of people, is immediately classified as lower class because it is a slum settlement. The idea that upper-or middle-class localities are safer for women is not located in any objective understanding of safety. This perception has its roots in a city that is rapidly becoming fragmented on class and community terms in the quest for clean sanitized environments. The real reason why they are perceived to be safer is the strong desire among the upper and middle classes to differentiate their own area as safe and not like lower-class spaces. There is also another popular myth that women are safer in their own localities. There is a sense that by drawing boundaries marking those who belong from those who do not, women will be safer. However, as we have argued at length earlier in this book, women are not necessarily safer in their own localities, only more policed. This surveillance may be seen as directly emerging out of a conservative vision of women’s safety which is located in the understanding of women as property rather than as citizens with rights. On the one hand, it is true that women who have proved themselves to be ‘good’ women might take liberties in their own localities when it comes to having ‘fun’—but this fun is certainly not of the variety that involves any kind of risk. ‘Good girl’ fun is highly limited fun. As women grow to puberty and reproductive adulthood, the demands to produce respectability increase. Both the spaces in which and the kinds of fun that women can have reduce after adolescence. Interestingly, though, as one crosses menopause and becomes visibly grandmotherly, the pressures to produce respectability may actually reduce. While older women do not need to guard their reputations as virtuous women, they battle the assumption that older women don’t desire to access the city as much as younger women or that they prefer to stay at home. Global capital has made pleasure related to consumption legitimate. However, this is a very limited understanding of pleasure. As we have suggested earlier, for women, middle-and upper-class privatized spaces might offer a kind of circumscribed and ‘protected’ fun, but this too is conditional. In this kind of fun, the risks are corporately calculated and managed by those who run malls, night clubs and other such spaces. And safety here has a price—the same space will not welcome a working-class woman who does not appear to have the means to buy commodities. It is only as a consumer, and a conspicuous one at that, that a woman can have fun here. This notion of fun is then inextricably tied to the act of consumption. As recent incidents have shown, despite the circumscribed nature of this fun, these spaces of consumption are also being increasingly threatened by right-wing fundamentalists breathing fire and brimstone at ‘Indian’ (middle-class) women’s increasingly western ways. In January 2009, a self-styled moral policing group attacked women who were lunching at a pub in Mangalore. Since then, a number of other such incidents have been reported in the region, including unprovoked attacks against women on the streets of Bangalore. Though these incidents have been geographically restricted to some parts of the country, they indicate a larger atmosphere of cultural conservatism brought on by anxieties about the very visibility of middle-class women without purpose, even in privatized public spaces.1 For that matter, those who do not consider women’s desire for fun to be immoral may still see it as frivolous or overly ambitious or risky. In some ways, it is true that seeking pleasure, particularly in public spaces, does come with its share of risks, chosen and otherwise. These risks include not only the risk of possible violence, but also the certainty of loss of reputation. However, not seeking pleasure in public holds the risk of never being able to access public space without purpose. None of this is intended to suggest that safety is unimportant or irrelevant but to underline our belief that the larger quest must be for a city where it’s safe for women to have fun. So what do we mean when we say ‘fun’? Social scientist Asef Bayat (2007) captures the essence of what fun might mean when he describes it as: … an array of ad hoc, non-routine, and joyful conducts—ranging from playing games, joking, dancing, and social drinking, to involvement in playful art, music, sex, and sport, to particular ways of speaking, laughing, appearing, or carrying oneself—where individuals break free temporarily from the disciplined constraints of daily life, normative obligations, and organized power. Fun is a metaphor for the expression of individuality, spontaneity, and lightness, in which joy is the central element. While joy is neither an equivalent nor a definition of fun, it remains a key component of it … [F]un often points to usually improvised, spontaneous, free-form, changeable, and thus unpredictable expressions and practices. For us ‘fun’ is also a verbal shorthand for pleasure, a concept that encompasses fun, but is much more than that. Pleasure itself is highly subjective and is inextricably linked to a range of choices including those related to sexuality, dress, matrimony (or not), motherhood (or not), to name some. Pleasure, might be found in solitude as much as in company; it involves the visceral body as much as the untamed mind; and it involves activity as much as simply doing nothing—in other words, loitering. Pleasure is an unknown quantity, which undermines the very possibility of order and control. This makes it potentially ominous and even threatening to society whose ideas of propriety are often centred on controlling women’s movements. As a woman, seeking pleasure then is a tall order. Pleasure is a distant dream when you are constantly being asked where you were, with whom and why, at what time and in what attire. Most debates on public space are disproportionately focused on danger rather than pleasure. This lopsided language of safety is often tied inextricably to respectability. This then discourages women from taking risks and in doing so, limits any fun that women might seek in the public. Because women’s right to take risks is not recognized, neither is the right to purposeless fun. A woman in search of unrestrained fun, who transgresses socially acceptable boundaries, is perceived to be at best stupid and at worst, morally reprehensible. Pleasure or fun is seen as threatening because it fundamentally questions the idea that women’s presence in public space is only acceptable when they have a purpose. It violates the boundaries of public and private by rendering them ever more fluid, by suggesting that for women, recreation may be sought now, not just within the home as members of families but as desiring individuals in the public. So what might a map of pleasure-seeking for women in Mumbai city look like? Having asked this apparently simple question, we find that there are no straightforward answers, even in this day of GPS maps. Only conjectures—that wonderfully complicated world of ifs and buts —that we explore more in depth in the chapters that follow.2 The use of the term ‘girls’ instead of the term ‘women’ in this section is self-conscious and is in no way intended to infantilize women. The intention is to reclaim the term ‘girls’ and interpret it in the spirit of desiring fun for its own sake, as suggested in the 1980s chart buster Girls Just Wanna Have Fun. It is this idea of fun, as non-productive pleasure, as taking risks and loitering, that we will explore as we traverse varied neighbourhoods and encounter different women across class, community, profession, geographical location, sexuality, marital status and age in Mumbai. 14. Can Girls Really Have Fun? If Bombay Girls are having fun, then certainly the place they are most visibly doing so is in Bandra, the queen of Mumbai suburbs. If you tell someone who lives in South Mumbai that you live in the suburbs, you might draw a blank. Say ‘Bandra’ and the smiles reappear. Bandra is comfortingly familiar, it is where South Mumbaiites sometimes go to shop, eat or otherwise entertain themselves; and where the fashions are as hip and the lounges more happening than in the city itself. ‘Bandra’ is also the answer you are most likely to hear when you ask young single women migrants to the city where they live. These women recount almost smugly that they can come home alone late in the night or go jogging in their shorts with little fear or discomfort. To them, this clearly justifies paying through their noses to live in this suburb. In that sense, Bandra is the ideal poster suburb for global Mumbai —young, heterogeneous, hip, cosmopolitan, modern and fun. And one can imagine if there ever is such a poster, it will be splashed with the image of the young Bandra woman shopping in branded stores or dining at an ‘in’ restaurant. So if this is the place where the ‘ideal desirable urban subjects’ we referred to in Consuming Femininity live, if this is where young women of means are apparently having fun, how much fun are they having? Does Bandra actually provide more access to public space for all women? In other words, can women take risks and loiter in Bandra? And concomitantly, what does the visibility of women do for ‘Brand Bandra’? It is important to underscore that the hip Bandra one imagines is usually only Bandra (West) that sits snugly between the railway line on the east and the Arabian sea to the west. Once a smattering of old Christian villages, today Bandra (West) boasts of several highrise buildings and some enduring old houses. It is a mix of communities ranging from Christians, Hindus and Parsis to Muslims, Sikhs and Jews. It also has a mixed class composition but because of its high real estate value and the cultural capital embodied in its schools, colleges, auditoriums, gourmet restaurants, designer boutiques and celebrity residents, Bandra (West) is often coded as an upper-class area in the minds of people. Bandra (East), on the other hand, with its large middle-class population and substantial slum population, was until recently seen as a poor cousin of the west —a hierarchy reflected in their starkly different real estate prices. However, with the growth of the expensive Bandra–Kurla Complex, all this is going to change. But for the moment, let’s stick to Bandra (West), since this is where women are said to have it all. Bandra is certainly the young professional woman’s first choice of suburb for reasons of safety and entertainment. ‘The reason I feel safe in Bandra,’ says a thirty-year-old corporate executive, ‘is because there are so many people like me living on their own here, doing the stuff we do, coming in late and partying late.’ Restaurants and bars in Bandra stay open late into the night and are often patronized by all-women groups. In the expensive Pali Hill market, women might shop for broccoli and yellow peppers in shorts and the vendor won’t bat an eyelid. Women discuss in congratulatory tones the ‘Bandra rickshaw driver’ who is used to seeing women out at late hours and who will not stare at them in the mirror. While it’s unlikely that vegetable vendors or the auto-rickshaw drivers in Bandra are any different from others elsewhere, what is being articulated is the sense that marks Bandra as being a space where professional women live, where there is a greater social acceptance for the long hours that they work, and where women are to be congratulated rather than censured for their professionalism. Given its predominantly Christian population, Bandra has an interesting gender history for women from the community who worked in the corporate sector even in the 1950s and 60s. The figure of the English-speaking, skirt-clad Christian working woman of Mumbai has been immortalized by Bollywood films like Junglee (1961). Usually, they were secretaries, comparatively subordinate in the corporate status hierarchy, but nonetheless they crossed the boundaries of the suburb and travelled to work in spaces that were not female dominated. The Christian history of Bandra, though much diluted over the last twenty years, continues to influence people’s perception of Bandra as being more liberal. However, there are no actual indications that the Christian community is any more gender-progressive than others. In fact, women in Bandra who live with their families in Shirley-Rajan or Ranwar or any of the other village enclaves have to contend with the surveillance that demands they perform the role of ‘good Christian girls’. For even if the rest of the city thinks they are liberal and ‘forward’, they know that sexual virtue counts (a lot) in the marriage market, especially since marriageable ‘boys’ might live in the next ‘village’. Even as their out-of-town-sisters, possibly renting little flats in the same villages, revel in their freedom, these young (and old) women must learn to ignore the censorious comments of fellow church-goers if they step out of line.3 It is the out-of-town women, originally from other (less welcoming) cities, and who now live on their own in Mumbai, who are most articulate about the pleasures of Bandra. ‘Even when I go with friends to a shady-looking bar at Pali Naka past midnight, it’s considered cool and acceptable in Bandra,’ says a twenty-something media professional from Jamshedpur. These women experience less of the restrictive watchful eye as compared to women who live with their families, although they are by no means free from the judgemental gaze of landlords and neighbours. The difference is that many of these women in Bandra, and now increasingly in suburbs like Andheri (West) and Versova, where many television and media professionals reside, live far away from their own families and relatives, and can shrug off these annoyances as the occupational hazards of living on their own. In one sense, women in Bandra do appear to feel a greater sense of comfort with their bodies—the rules of decorum in clothing are less rigid and the boundaries are wider—but the pressures to produce respectability remain unchanged. The definitions of this respectability, however, are specific to Bandra. Where women are willing to play the roles they are expected to, as well dressed, conscientious professionals and savvy slim consumers, they are rewarded with a greater degree of comfort in the public. So, while Bandra is an old suburb, it is also new in the ways the suburb has been made and remade in the last fifteen years in the image of the desired global city-suburb. The Bandra Bandstand and the Carter Road promenades have been taken over and ‘beautified’ by middle-class citizens’ groups premised on the exclusion of those defined as the ‘undesirables’. So while there are designated parks for expensive pedigreed dogs, street children might be discouraged on the promenades. Lower-class men still induce anxiety and as elsewhere in the city, it is now difficult for Muslims to find housing here. At the same time as the numbers of restaurants, pubs and fashion boutiques multiply in a plethora of mind-boggling options, more of the city’s beautiful people (read models and film stars) move here creating more reasons to ‘Celebrate Bandra’, the suburb’s own festival.4 In one sense, Bandra is what twenty-first-century Mumbai wishes to be in its entirety and the presence of women is integral to this aspiration. As much as Bandra offers women some breathing space, so also women who access these spaces as professionals, commuters and consumers reinforce Bandra’s reputation as a trendy, up-market and safe suburb for women, allowing, among other things, its real estate value to remain high. The presence of modern and respectable women in Bandra, underscores its aura of desirability. One might then argue that as much as the environment of an area influences and shapes the ways in which women might inhabit it, so also the visibility, or lack thereof, of women has important implications for how the socio-cultural life of that area is perceived. This is true as much for a place like Muslim-dominated Dongri where the good woman is veiled and apparently silent as for a place like Bandra where the desirable suburban subject is a professional and a consumer. By the standards of a global economy where visible consumption is a marker of ‘fun’, Bandra girls are certainly out there. But does being ‘out there’ indicate an unrestricted claim to public space? Perhaps not. For, of course, there are rules and restrictions. We can hang out in the coffee-shops and night clubs but sitting ‘on the rocks’ at Bandra Bandstand or the Reclamation promenade with our boyfriends is still frowned upon. We can have smoked salmon and anchovies express delivered to our doorstep but in many cases our bhelwallah has been booted off the streets. We can jog on the ‘citizens’-committee-beautified’ promenades but cannot bite into a bhutta for eating is forbidden lest we dirty the place. We can have our bit of fun if we accept the limits: we can wear short skirts but not picket for equal rights—for surely, as many might say, what more could women want? 15. Do Muslim Girls Have less Fun? If we imagine Bandra girls as having the most fun in the city, the Muslim girls of Mohammed Ali Road might appear to have the least fun. The image of the poor little Muslim woman trapped in her burkha with ‘fundamentalists’ and ‘criminals’ as neighbours in her crowded mohalla dominates popular perception. Their lives are assumed to be joyless, devoid of any pleasure or playful indulgence.5 But if we ask the girls of Dongri, Nagpada, Cheetah Camp, Behrampada, and even Mumbra, they might not agree. Says one, a sixteen-year-old Dawoodi Bohra girl from Bhendi Bazaar, who wears the Bohri veil every day, ‘We can go everywhere in the ridha, I don’t feel any different from other girls.’ Her friend concurs, ‘We go out for movies, shopping, to restaurants, to the gym, park, do whatever other girls are doing.’ Adds another who lives near Pydhonie, ‘We even bunk class, eat bhelpuri outside college, or sit on Marine Drive.’ Sometimes, their dress might make them stand apart, but otherwise, their lives cannot be distinguished from those of other teenage girls in the city. Yet the perception of Muslim-dominated areas of the city is that they are dangerous and uncool (except perhaps during the fasting month of Ramzan when the aroma of seekh kebabs and malpuas sold on the streets late into the night attract their fair share of gourmets). Regular media reports of the criminal gangs of Nagpada, riot-prone Dongri and the orthodox clerics of Mumbra only add to people’s suspicions. As discussed in detail in the chapter ‘Unbelongers’, negative feelings towards Muslims prevail across lines of class and locality, particularly after the 1992–93 Mumbai riots. A significant aspect of this perception is people’s ignorance about Muslims and Muslim neighbourhoods. In the last two decades, Mumbai, as also the rest of the country, has become increasingly communalized and intolerant towards its minorities, particularly Muslims. This has had an adverse impact on Muslim women’s access to public space. In Mumbai, divisive boundaries increasingly ghettoize Muslims by denying them access to housing in mixed community areas. This heightens the policing of women’s activities in public and legitimizes restrictions on their mobility. Educational and employment opportunities are monitored carefully and the surveillance of leisure activities is even more stringent. Like women in other communities, Muslim women too face fewer restrictions in accessing places of apparent purpose, like the market or the jamaatkhana (community hall). A lecturer at a South Mumbai college was forbidden by her brother from walking in a park at Mazgaon. ‘He told me to go a ladies’ gym instead,’ she said. The anxiety was about her being seen by ‘outside men’ and the possibility of her meeting the wrong kind of men there. A more menacing level of policing is encouraged by neofundamentalist groups, which in the past decade have become more influential. Many attribute the rise in the number of women taking to the burkha to the increased religiosity being fostered by such groups. Schools run by these groups promote the segregation of girls and the limitation of their activities outside the community, including sports and music. Women’s bodies and mobility are also policed and regulated through fatwas. And it seems as though they are particularly intent on focusing on the fun aspects of women’s lives—from banning women from wearing lipstick or putting flowers in the hair to blocking cable TV access, singing and dancing at weddings and visiting restaurants. In Mumbai, the impact of everyday community policing, fatwas and coerced veiling is particularly felt by those women who live in homogenous inner-city areas such as Dongri and Bhendi Bazaar, and more acutely by those in the ghettoized belts of Malvani in Malad and Mumbra. ‘The focus is “aas paas ke log kya kahenge” or what will our community people think or say when you wear such clothes, come home late, hang out on the road,’ said a young Nagpada resident, who finds her aunt’s family in Bandra quite relaxed in comparison. Our research shows that Muslim women who live in mixed community areas of the city such as Bandra and Andheri (East) have much greater access to public space and the public sphere. As we well know, even in seemingly impossible situations, women are usually able to manoeuvre and create choices for themselves. As in other parts of the city, in the mohallas, too, it is the women who conform or at least appear to conform to the norms who are best able to strategize to have fun. The more intrepid ones use a mix of practical strategy and panache to enhance fun for themselves. A twenty-nine-year-old in Mumbai Central, who is constantly told not to wear jeans, regularly packs them into her bag and puts them on later at a friend’s house. Others use college restrooms and even the back seats of cabs for a quick change of attire or a dab of make-up. The less rebellious ones may content themselves by wearing jeans only in the safe confines of their home, not daring to disobey familial and community diktats. Women who wear the burkha also use it strategically—sometimes even jazzing it up with sequins, lace and embroidery to make it more fashionable—in order to access public space for both work and leisure. Others sometimes take off their burkhas where it may hamper their movement or draw unwanted attention. For instance, one young Muslim wife is urged by her husband not to wear the burkha when they are out for a late night film or at a coffee shop. ‘He feels that we can then be more intimate and draw less attention to ourselves,’ she said. Another young Muslim woman, a medical student, takes off her burkha in the local train on her way to college but puts it on before she enters her mohalla. For Dawoodi Bohra women, often being part of a maineeg, which is an informal community-sanctioned friendship group of Bohri women, gives them the freedom to access public spaces legitimately. The members of such groups grow up together and meet regularly to have fun in restaurants, malls and movie theatres. The Muslim lunar month of Ramzan, when all Muslims are obliged to fast from sunrise to sunset, is another time for Muslim women to stay out late at night, mainly with family or close friends, to enjoy the iftar feasting and shopping on the streets. Among the reasons for this is the presence of many people and the increased street lighting (due to all the street stalls being lit up) that facilitates women’s access to public spaces during this month. The access that Muslim women in community-dominated ghettos have to fun and pleasure is very similar to women who live in other community-dominated neighbourhoods. But while a Gujarati Jain woman in a building or locality dominated by her own community might feel just as restricted, Muslim women are further constrained. They are also compelled to assume more risks, real and imagined, simply because they live in and belong to a specific minority community which is viewed with a high degree of suspicion. In Muslim-dominated community areas, men are often seen as potential terrorists and themselves experience an anxiety related to public spaces that would be completely foreign to Hindu men like them. Unlike Hindu men, Muslim men cannot take for granted a sense of belonging in the public. Nor can they take the same kinds of risks for fear of being seen as a threat. Similarly, Muslim women’s capacity to engage risk in public is inextricably linked to their entire community also being able to take risks. The lives of Muslim women are not joyless because they are Muslim, but they may end up finding less space for fun because of the intolerance faced by the entire community. If it is external prejudice that often forces Muslims to live in ghetto-like situations and be policed by the more fundamentalist elements in the community, then it is the same prejudice that also adversely hampers Muslim women’s access to more avenues for pleasure and fun. By the standards of the global city, Muslim women may indeed be having less fun. Unlike the ‘ideal’ Bandra woman, who is also simultaneously the ideal ‘global’ Mumbai woman, the apparently ideal Muslim woman would seem to be the antithesis of the desirable global female subject. In popular perception, they stand to subvert the self-image of Mumbai as a contemporary modern, cosmopolitan, global city. And as elsewhere, the atavistic image of the Muslim locality is situated in the figure of the burkha-clad Muslim woman. This image has implications for how fun itself is defined. Sequinned burkhas at iftar parties might actually be as much fun as wearing spaghetti straps at a prestigious club. However, while the latter fits into the larger narrative of fun for the city, the former is perhaps not just different but also not recognized by the city as being fun at all. Thus, for Muslim women having their idea of fun acknowledged as fun is perhaps as important as expanding the boundaries of their access to pleasure. Given the denial of access to public space for all Muslims, it is not surprising that Muslim women have little claim to the city’s public spaces. The rights of all Muslims to access public space, the rights of all Muslim women to access public space and the rights of all women to access public space are thus inextricably linked. When our brothers and fathers are looked upon with suspicion in public space and our entire community is villainized, what are the ways in which we can claim our rights to pleasure as women? 16. Do Rich Girls Have more Fun? If wealth equals fun, then the rich girls of Mumbai should be having the last laugh. But that’s only one way of looking at it. Chances are that some of them are also being shadowed quite closely by their mummies and papas, particularly if they are single. So the cell phones in their oversized Louis Vuitton bags ring incessantly, the chauffeurs keep a watchful eye and friends are closely scrutinized. For designer hipsters and halters aside, the comings and goings of the rich girls—and here we mean the seriously wealthy business families—are policed quite stringently. As one woman living on Nepean Sea Road pointed out, ‘I have to call my parents all the time to tell them where I am.’ A college student from Malabar Hill added, ‘There’s no way any boys from my class can call me at home.’ Wealth, and the fear that it may pass into the wrong hands, if daughters and sisters break the iron-clad norms of marrying within community, caste and class, generates strict surveillance. At one time, many elite neighbourhoods of the city, mostly consisting of old bungalows with gardens, were relatively heterogeneous in terms of communities, though homogenous in terms of class. That heterogeneous mix is fast disappearing. For example, upper-class South Mumbai areas are now largely populated by business families who often tend to live close to their own communities.6 For an outsider to these communities, it has become increasingly difficult to rent or buy a place in these neighbourhoods. As argued in the chapter ‘Good Little Women’, homogenous areas facilitate enhanced surveillance of women. Young women living on Malabar Hill, in buildings occupied largely by members of their own community, record that they continuously feel the oppressive presence of their censuring gaze. Where caste and community endogamy are strongly practised, women’s reputations are paramount and directly affect their future marital prospects. For some of these women, their access to the privatized public actually expands after they marry appropriately. The birth of children further expands access. However, the need to reinforce one’s respectability over and again never quite goes away. Inappropriate marriages often extract high prices. Even when there is no overt violence, there are covert, but no less real for that, signals that transform insiders into outsiders. On Altamount Road, one young Gujarati Jain woman painfully recounted how she was seen differently by former neighbours in her parents’ all-Gujarati building after she married a man of another community. She said, ‘Somehow, I feel that the people in my mother’s building, whom I knew well earlier and who treated me like their daughter, are now uncomfortable with me.’ Sometimes, it doesn’t even have to be another community—it could simply be a non-vegetarian from the same religious community who is unacceptable as a marital alliance. In our discussions, rich women from Malabar Hill, Nepean Sea Road and Peddar Road articulated their fear of crowded local trains, strange smells, unpredictable streets and footpaths, and of the gaze, particularly of the lower classes. Among most women, we encountered anxieties related to negotiating the class and community ‘other’, but nowhere was it as heightened as among the wealthy women of the city. What keeps them away from the public space, or even expressing the desire to access public space, is the fear that they have been taught not just of street sexual harassment, but of anything unfamiliar to them. As one young woman put it, ‘I don’t like going to unknown places in the city, it makes me very nervous.’ In these wealthy neighbourhoods, the streets are often peopled only by the domestic staff. One reason why rich women here perceive even their own neighbourhoods to be unsafe at night is because the domestic workers and chauffeurs are free from their duties at that time and the men hang around the streets. There is an acute awareness of the lower-class gaze, where any hint of an interaction with the male domestic staff outside their roles as employer and employee is a strict nono. Moreover, there is also a fear of the gossip grapevine that circulates through the domestic workers and finds its way back into other rich households. This gossip has the potential to tarnish women’s reputations. While women might be policed, wealth does provide access to specific infrastructure that enhances women’s capacity to produce safety for themselves, the most important of these being transport, especially in a large city like Mumbai. In a group discussion, when the conversation turned to commuting in the city, one woman admitted, ‘Sometimes, when no car is available, I may take a taxi.’ For many wealthy women, occasionally taking a taxi is the extent to which they use ‘public transport’. At all other times, they drive their own cars or are driven around by family members or chauffeurs. As a result, issues that other women encounter on an everyday basis, such as not being able to wear certain types of clothes or going out after a certain time in the night because of a fear of being verbally or physically assaulted, do not arise for upper-class women in quite the same way. These privileges, however, are not without conditions. Fundamentally, safety is bought at the cost of the prohibition of all risks; for the entry of rich women into public space is really a misnomer. What they actually do is move from one private space to another, facilitated by the air-conditioned tinted private glass bubble that is a luxury car. Rich girls might appear to be out there but actually, they do not access public space at all. Pleasure then is sought in private spaces: lounges, fashion shows, private parties, boutique spas, launch parties, celebrity lunches and increasingly, art shows and fund-raisers, which have become spaces where they can unwind with others like themselves. If that gets boring, it’s only a jet stop away to the beaches of Goa, Balinese dance bars, Milanese fashion shows or New York restaurants. The capacity to buy pleasure, in other words, may open up the world to the woman’s discretion, but it is a world contained in private spaces. So do rich girls have more fun? If fun is defined as consumption, then surely they do, but if fun includes multiple choices in regard to accessing the public, as well as meeting different kinds of people, then the answer must be more cautious. In some sense, rich women have access to the same privileges as rich men, but in other ways (which sometimes even includes access to education and employment), they have much less than their brothers. From the perspective of the usage of public space in the global city, rich women represent the ideal prototype of what all women should be: seemingly visible, without actually accessing public space at all. In fact, they remain ensconced in the privilege of the city’s conspicuous private spaces. These spaces are hyper-visible, appearing each morning at people’s breakfast tables on the glamour- struck Page Three. This public visibility might make us forget that these are, in fact, very private and protected spaces. For rich women, the only public access they might find is when they actually leave the country. In other world cities, where their reputation cannot count, the neighbours aren’t watching and the service staff are unfamiliar, they can let down their hair even in the public. If we can stroll in Kew Gardens, picnic in Central Park and sunbathe in the French Riviera, why shouldn’t we be able to do so in our own city? 17. How Do Slum Girls Have Fun? If you are poor and a resident of Slumbay—as more than 50 per cent of Mumbai’s inhabitants are—do you even have the space to have fun? Imagine 6.5 million slum-dwellers living on 8 per cent of the city’s land, often forced to share a creatively pieced together house of tin and plastic measuring no more than eighty square feet with at least eight others; enduring several hours at the community tap before it trickles forth a bucket of water; waiting for the cover of darkness in order to defecate. When the harshness of everyday life never seems too far away, can a woman even begin to think about having fun? The slum is imagined as a monstrosity, a space of chaos and anarchy, of people living beyond the pale of civic life. In reality, however, slums are ordered along a complex network of social, economic and community relationships and are heterogeneous in their class and communal composition. The multiple uses of space— with homes, home-based industries as well as karkhanas (work units), shops, schools, temples and dargahs—means that someone is always watching the street and strangers are conspicuous. Thus, contrary to popular perception, the slum is actually also quite safe. The poor inhabitants of slums contribute their labour to the city, but are not provided basic services like housing, electricity, water and sanitation. A majority of slum-dwellers work hard in the informal sector, disputing the image of slums as unproductive spaces. A large part of the city functions on the basis of the cheap products and services they provide.7 Despite their productivity, slums remain an embarrassment to the vision of a global Mumbai, a reminder of its third worldness, a blemish to be cleansed. The idea of contamination is transferred from the slum to the slum-dweller, allowing active violence against them. This violence is visible in the grossly inadequate infrastructure: the lack of public toilets, potable water and sewage, all of which pose a health hazard for slum-dwellers, and has particularly adverse implications for women. For instance, in Dharavi, some women have to walk across half the basti to get to the common public toilet, an act which raises concerns of safety, particularly at night. Marginalized from the city, both literally and metaphorically, what kind of access do slum women have to pleasure? The question of access in slums is to a large extent a question of spatiality or the arrangement of built structures. The manner in which individual houses are built creates narrow streets with doorways facing each other, often not more than three feet apart. This produces particular social uses of space, given that the house itself is barely more than one room, it is not uncommon to find activities spilling out into the street. Thus, the street becomes an extension of the home. Ideas of kinship are transferred from villages and all the boys from the same street are classified as brothers. This has dual implications—the ‘sisters’ and ‘brothers’ are sexually off limits to each other, and a network of protection for the sisters is established so long as they stay within the lane and behave in accordance with the ‘rules’ that the brothers set. It is only when one leaves the bounds of one’s street that one actually goes into public space. On the street itself, the distinction between the private and the public is blurred. Thus, in Govandi’s Bainganwadi slum, a young unmarried Muslim girl says, ‘I feel safe in my own chali [lane]. I don’t feel the need to wear a burkha. But I am not allowed to go to the next lane without my veil.’ She adds that girls are also never sent to stand in the line for tanker water, since that queue is formed on the main road where young men who are strangers usually hang around to stare and whistle at the girls. With spatial boundaries so clearly defined, it is not surprising that the access of slum girls to the world outside their homes is limited. As elsewhere, women who go out to study or work have a certain degree of access to public space, provided they are careful to demonstrate that they are not abusing this ‘freedom’. The situation in slums is, in some sense, the converse of the situation in wealthy neighbourhoods. While in Malabar Hill, women have little or virtually no access to public space, but plenty of access to closely monitored privatized spaces, women in the slums of Dharavi, Behrampada and Bainganwadi have limited access to public space, but almost no access to private space, so much so that finding a space even to defecate in privacy is not always easy. Given that a woman in public is often perceived as a ‘public woman’, in the absence of any privacy, slum women have to viscerally underline their respectability. Where there is no clear boundary between public and private space to speak of, the burden of marking the private body falls on the habitus of the woman—how she walks, what she wears, whom she talks to or even looks at. Women have to demonstrate their private location with every movement they make, wearing their privacy like a protective cloak. At one of our focus group discussions, young men and women from Dharavi debated the codes that distinguish ‘good’ girls from the ‘bad’, suggesting that there are complex and shifting rules for how ‘good’ girls should behave. For example, if a girl is caught talking too frequently to the same boys, then she is labelled ‘chalu’ (loose) and rumours about her morality begin to spread. In some cases, women who reply to harassment are seen as encouraging it; in other cases, the sternness of their tone is taken as an indicator of their lack of tolerance for harassment and may stem it. On familiar terrain, women who have already established virtuous reputations as ‘good girls’ can often repudiate harassment by assuming the moral high ground. Nonetheless, as one young woman complained, ‘There is no foolproof way of avoiding being sexually harassed.’ In other words, girls have to acquire the practical strategies and skills of negotiating multiple ambiguities of tone and posture through trial and error. The moral concerns with regard to young women in slums are the same as elsewhere, only here, they are heightened by the proximity in which people live and the impossibility of anything being a secret. Whether in a large slum like Dharavi or on pavement settlements as on P. D’Mello Road, ideas of boundaries are deeply entrenched. This has far-reaching implications for women’s access to public space. For instance, in Dharavi, older Maharashtrian women said that they did not allow their daughters to go outside the community lanes without an escort because, according to them, the ‘Madrasis’ and ‘Muslims’ would harass them. The presence of young single men working in the neighbourhood, who are seen as predatory towards women, exacerbates this fear. To avoid unwanted pregnancies and elopements as much as sexual assault, young girls are often withdrawn from school and married off early. For slum women, their homes are filled with ailing grandfathers and squabbling siblings, and the street is an extension of the home, peopled by a quasi-extended family. In this context, they often choose to access fun outside their own neighbourhoods. Pleasure might be found in going to a film or walking along the promenades in Bandra or Dadar. Women also say they go to parks in other areas like the Maheshwari Udyan in Matunga or the City Park in Bandra East. One young mother pointed out, ‘Sometimes, we feel so cooped up that we don’t even mind paying an entry fee to get some fresh air and space in a park.’ It is not as though slum areas are entirely devoid of public spaces, but as happens elsewhere, these tend to be occupied largely by men. It is only at raucous community and religious festivities or during stolen moments of privacy that pleasure is to be found. Our research clearly suggests that even though slum women want private spaces, especially a toilet, they also wish to access public space for fun and when offered opportunities to do so, grab them with both hands. In Dharavi Koliwada, for instance, which is an old fishing village now surrounded by the large slum settlement, in the week preceding Holi, women take to the streets every night, singing, dancing and playing games into the early hours of the morning. Such events provide a space where the stringent norms of respectability are relaxed. As the city seeks to ‘redevelop’ these spaces, the new housing forms replacing slums in the last few years under the various slum redevelopment schemes may offer even fewer opportunities for women to have fun. The debate for and against these schemes obsessively focuses on the provision of 225 square feet of residential space. The public discourse becomes only about this number and ignores the other formal and informal institutional structures that are an essential part of any neighbourhood. These include schools, primary health centres, crèches, local clubs, and mahila mandals. It also disregards the fact that many women in slums use their homes as work spaces. It also ignores the existing forms of community life, which are the prime spaces where women might find pleasure. Studies on the resettlement of slum communities show that a movement from horizontal structures to vertical apartment blocks creates a greater sense of physical insecurity and often restricts women’s mobility further, even for education or employment, much less fun. While the city frames our lives within the narrow contours of slum rehabilitation schemes, often, little more than tricky number games, might we be so audacious as to demand public spaces for pleasure? 18. When Do Working Girls Have Fun? Ms Professional in the new global city is the white-collar worker. She could be a CEO, personnel manager, investment banker, corporate lawyer, executive assistant, secretary or receptionist. She might arrive in her chauffeur-driven car, drive herself to work, use the local train and share-a-cab or jump on to the bus from the nearest station. She might be wearing a starched cotton saree, a designer or off-therack salwarkurta, a formal skirt and blouse, or a sharp business suit. She will at least have a graduate degree and, in many cases, a postgraduate or professional degree, or even a doctorate. Her professional and class profile differs very little from her male colleagues. In their branded striped shirts and grey trousers, sometimes with a jacket thrown over an arm, with a laptop bag on the shoulder and files in their hands—these are the hard-working girls of Mumbai’s business districts of Nariman Point, Ballard Estate, or the BandraKurla Complex. They are also found in the new office complexes of Lower Parel, Andheri (East) and Malad. Sporting a ‘I can deal with it, whatever it is’ attitude, these girls work around the clock and commute at odd hours. Having any fun along the way, you may well ask.8 In the age of double-income globalization, when ‘career’ is no longer a dirty word, femininity can be redefined a little for professional women. Women are allowed to be ambitious for themselves and aspire to the corner office with the best view. It’s all right, even commendable, to work late. In fact, during a focus group discussion at Nariman Point, a group of women professionals competed with each other to demonstrate how late they worked and to suggest that, as professionals, they could handle themselves and the city. The reputation for working hard may for these women enhance rather than detract from their desirability in the matrimonial market and, of course, there’s always the chance that they will find their own well-placed professional husbands. Nonetheless, despite these changes, the negotiations with work, work space, colleagues, commuting and public space are not quite the same as those of their male colleagues. In the marriage stakes, professional careers are all well and good so long as women realize that these are always secondary to their primary roles as wives and mothers. The women who don’t acknowledge this often get represented as hard-nosed and inevitably headed for the divorce courts. An example of this is the character of Riya played by Preity Zinta in the otherwise not-so-regressive Bollywood film Kabhi Alvida Na Kehna (2006). A long-hours-in-the-office, upwardly mobile media professional, she finds herself berated for being an absent mother and wife, whose husband eventually cheats on her. In the same vein, most advertising that uses images of professional women underlines either their femininity (how good they smell or look) or their mothering skills (how they cook, clean and nurture at the same time). Even in the workplace, working long and hard is good so long as you don’t rise too quickly or faster than your male colleagues. As a young software professional in a multinational company told us, ‘If you get promoted too quickly, people always make veiled comments about how you got there and if you complain, you get labelled as unprofessional.’ Similarly, while working late is perfectly fine, playing late may leave one open to the worst kind of conjecturing. As one political journalist put it, ‘Being a pal is all very well, but one needs to be very clear about where you stand; otherwise it’s so easy to be misunderstood by men colleagues.’ Good women don’t play unless it is in the company of boyfriends or husbands or, occasionally, other women. Acquiring the reputation of being a ‘good time girl’—out every night of the week drinking with the boys—is certainly not a good idea. Respectability is also vested in the way professional women use or abuse their femininity. Magazines advise them on how to dress in a way that is ‘sexy but not provocative’: the lipstick can only be so bright, the skirt only so short and the neckline only so deep. All of it finely orchestrated to walk the thin line between being a feminine woman and a gender-neutral professional. If shouting about your sexuality is a no-no, flaunting symbols of religion is also to be avoided. Some symbols are predictably more acceptable than others —wearing a bindi to work might be okay, but never a burkha. Other symbols, especially subtle matrimonial ones like a delicate unobtrusive mangalsutra, may even help endorse respectability. Our study of working women in Nariman Point demonstrated how women here, like women elsewhere in the city, manufacture respectability in the way they access public space. Following people and mapping their routes during lunch time shows that while many men go down to the street from their offices to eat alone at the various food stalls in the area, and often linger around before and after lunch, women rarely do so, usually preferring to order lunch. If they do go downstairs, it is mostly in the company of others and even then they usually go straight to the desired stall and head right back up after lunch—they cannot appear to be loitering. Business districts are particularly unfriendly to women because the streets become empty at night. A headcount of men and women at different times in the day showed that the streets of Nariman Point have one of the lowest female: male ratios in the city. A comparative count at 10 p.m. showed the percentage of women here at 8 per cent as against 21 per cent in mixed commercial–residential areas. Mixed-use spaces allow women to access public space more easily so that they feel safe in them. The absence of hawkers in the Bandra–Kurla Complex and the recent drive to remove hawkers from the streets of Nariman Point, has meant that these streets become even more isolated and thus feel uncomfortable even during the day. As one corporate lawyer put it, ‘I feel safer when there are hawkers winding up business on the road as I am leaving office late. That way, there are people and lights, and it just feels friendlier.’ While hawkers might provide a sense of safety in these whitecollar business districts, in some other contexts, such as the Maharashtra Industrial Development Corporation (MIDC) area in Andheri (East), the lower-class male is often perceived as a source of discomfort for professional women. Since the MIDC employs a mix of white collar and blue collar workers in its jewellery, infotech and BPO industries, it is seen as a space where ‘undesirable’ men also work. There is an anxiety attached to this mixing of classes— where middle-class women interact with working-class men on an everyday basis. This anxiety is also related directly to the fact that while professional women are desirable subjects of the global city, lower-class men are its explicit undesirables. The difference is that in these industrial areas, there are more lower-class men than usual and they belong there in a way that hawkers in the upper-class business districts do not. They work here and cannot be ‘cleared out’ at will as the hawkers can. This space is peopled largely by men and coded as a visibly male space. The overwhelming presence of men creates a context in which gender, rather than class determines power equations of the space. As against Nariman Point or Ballard Estate, where professional women might wield their class as a shield, the industrial area is clearly masculine, making middle-class women even more out of place than they would be elsewhere. This mix of class and gender in the workplace also determines which professions are seen as respectable and therefore desirable for women. At the top of the heap are professions where women don’t have to deal with men in any significant way, such as school teaching. Close behind are those professions where women work with men of their own class or upper classes such as white-collar workers in white-collar-majority areas. The reason middle-class women in working-class areas induce high levels of anxiety is not so much the fear of assault as of consensual liaisons between women and men across classes, that is, of middle-class women with lowerclass men. Where women work in professions or in spaces where classes mix, they are compelled to underline their respectability even more through symbols and body language. Professional women are often compelled to produce performances of gender neutrality in the workplace and super-womanhood at home, both of which require skill, time and effort. While these women might try hard to neutralize their gender in the workplace, this does not mean that spatial gender restrictions do not apply to them. Whatever rung of the corporate ladder she may occupy, this woman must produce a carefully calibrated blend of professionalism and respectability. To be a ‘good girl’ is not quite being one of the boys. It helps if one has a boyfriend (or better still, a successful husband) tucked away to produce at office parties—establishing thereby one’s desirability and demonstrating that one is ‘spoken for’ (and therefore, off limits) at the same time. The good professional woman is expected not to bring gender or any gender-related ‘excuses’ such as child care, household work, discrimination, sexual harassment or safety concerns into the workplace. She is required to take in her stride the absence of working elevators in the office building after 9 p.m. and never say, ‘I can’t walk alone down the stairwell after work at night because I’m afraid of being grabbed and assaulted.’ This is the woman who deals with her fear of late night commutes by holding on to her mobile phone, ready to dial home ‘just in case …’ and the one who dons the mantle of the ‘neutral’ worker at all times, never upsetting the veneer of equality of the sexes in the workplace. Pretending we are not women might get us the coveted promotion and even the respect of our peers, but is of little use when we need to access the stairwell at 2 a.m. in the morning or catch a late night or early morning flight to another city. In a context where becoming neutral professionals has failed to give us equal access to public space, isn’t it time we leverage our identities as women and make a political claim to public space as women who have equal citizenship rights? 19. May Night Girls Have Fun? Every weekday night, Richa metamorphosizes into Rebecca and Archana becomes Amanda as they step into their brightly lit offices that simulate daylight, ready for yet another nine-hour shift on the phone. Taking calls that originate thousands of miles away, carefully using ‘neutral’ accents, and assuming an alien cultural identity, these are the new ‘voices’ of the global Indian economy. What makes these women different is that they work mainly at night, a time and space still largely forbidden for Indian women. For darkness is a time when good girls are expected to be virtuously at home; when only the bad girls are outside, engaging in ‘disreputable’ professions. So what happens when the demands placed by globalization create a whole new industry—one that works on Eastern Standard Time (Greenwich Mean Time +5 or Indian Standard Time +10.5)—which seeks to employ middle-class, English-speaking women and makes them monetary offers that are hard to refuse? The stage is clearly set for all kinds of anxieties about women, including, among other things, those about safety, clothing, sexuality, morality, money and reputation. Till recently, it was assumed that if a woman was out at night, she was up to no good. Sex workers plied their trade after dark. Bar dancers worked late into the night too. Others who commuted late included those in the hotel and hospitality industry and those in various areas of the medical profession, especially nurses working on a rotating shift basis. With the exception of nurses, who could be seen as nurturing Florence Nightingales, the other women mentioned above have been looked upon as being of questionable respectability. In fact, good, hard-working women weren’t even legally allowed to work at night, for according to the provisions of Article 66 (b) of the Indian Factories Act, 1948, the night was out-of-bounds to women. The time regulation in this Act made it illegal for women to be employed between 7 p.m. and 6 a.m. The Act was only amended in 2005, providing more flexibility in the employment of women during night shifts, to fit the demands of new globally linked businesses like the Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) industry. However in various states, provisions of the Shops and Commercial Establishment Act, 1958, continue to be used to prevent women from working at night and these have to be independently negotiated by employers and employees. Other obscure and apparently unconnected laws and clauses too can be invoked to keep women from working at night. In Mumbai’s Pydhonie area, for example, local police persuaded the excise department to revoke work permits issued to women working as waiters in bars—these permits usually allow women to work till 9.30 p.m.—on the grounds that this would prevent them from surreptitiously working as bar dancers and also reduce crime. The police also averred that it was dangerous for these women waiters to make their way home after work as the area was predominantly a business district and thus quite deserted after dark. What the police failed to mention is how, by revoking the work permits of these working girls, they conveniently reduced their own policing duties.9 Given this prohibitive scenario, when the ought-to-be-good-middleclass women begin working at night, it sets a very large cat among the pigeons. As one call centre employee told us, ‘If you tell people that you are working in a call centre, they don’t really take you seriously because they think that it is only fun and games. And there is this connection, the call centre-‘call girl’ thing. It comes from the feeling that girls shouldn’t go out at night. So when they see girls getting ready and going out, they wonder where they are going. Are they actually going to work, at this hour?’ If good girls don’t work at night, and the girl leaving home for work at 11 p.m. is your cousin, or niece or even your daughter, then surely the definition of what constitutes a ‘good girl’ must expand? As the numbers of women employed in call centres grows exponentially, the sticky questions only multiply. The National Association of Software and Service Companies (NASSCOM) estimates that the Indian ITBPO industry—which generates revenues worth several billion dollars—has emerged as the largest private sector employer in the country with a direct employment of 1.6 million professionals, of which an increasing number are women. This growing number of women employees, however, continues to be concentrated at the junior levels as men still outnumber women at the higher levels.10 The safety of these new ‘night girls’ is a very real concern. In recent times, there have been some highly publicized cases of women being assaulted while commuting late at night, which has created a sense of panic amongst the women employees and their families. In December 2005, a HP Globalsoft employee in Bangalore was raped and murdered by a man who pretended to be the company car’s driver. In November 2007, a Wipro employee in Pune was also raped and murdered by the driver of her vehicle. BPOs have responded by increasing security and training women employees in self-defence. In some cases, women employees are now accompanied by armed guards while commuting. In some call centres, women are not allowed to travel alone with the driver. As Reena Patel (2006) recounts in her study of one call centre, vehicles carrying six to eight employees were used and where all the employees were female, a security guard would accompany them in addition to the driver. If one of the employees was male, then there would be no security guard, but the male employee would be dropped off last. Interestingly, this measure was employed not so much for safety, but because there had been reports of the Mumbai Police stopping the vans and accusing the women of doing sex work. Even identity cards were not deemed adequate proof without the legitimizing presence of a male escort. Physical safety, then, is only one concern. The other anxieties are more palpable: how does one distinguish call centre girls from sex workers, often colloquially referred to as call girls? And further, what happens when women work late at night in closed confines and in close proximity with men? Do sexual norms change? Will people cast off their identities as good Indian men and women as easily as they assume foreign names and accents? Will women then cast off their Indian ‘family values’ and disregard their reputations? These fears centred around morality in call centres abound as the youth are perceived as being corrupted by easy money and westernized lifestyles. A popular narrative imagines call centres as spaces where sex and drugs are rampant and men and women share cigarettes and bodily fluids with equal ease. One news item reported that at a call centre office in Bangalore, the drains were found choked with condoms.11 Several other newspaper reports suggest that after work, the co-workers, living in their own time zones, have wild parties with alcohol and casual sex. Doctors interviewed in the BPO cities report an increase in the numbers of women seeking abortions and one doctor was quoted being sanctimoniously shocked by the fact that the women do not feel guilty about being ‘promiscuous’ (her words, not ours).12 This doctor is not alone in her fears. What she articulates is the more generic fear of what might happen when women are let loose in a world where they might ostensibly claim all manner of freedoms that they are not expressly permitted to enjoy. Many families remain sceptical about their daughters working in BPOs—sometimes, they do not view it as a ‘real’ job with future prospects, sometimes, they are simply concerned about them working at night. Neighbours and housing societies can also be prejudiced against women who work at night, sometimes even formally objecting to their timings. It is not surprising then that these fears often affect matrimonial opportunities. Many of the women working in call centres are young, usually between eighteen and thirty, and single. One woman we interviewed, a team leader at a call centre, said, ‘I think our matrimonial chances are affected. People who belong to other industries do not understand BPO people at all. There are people who marry outside the industry, but later they quit the job.’ Another woman who works as a trainer said, ‘Call centre employees often tend to marry each other. We understand the problems involved.’ Recognizing these fears and in an effort to counter them, some BPOs have what they call ‘family days’ when the parents of the ‘good girls’ can come and inspect their place of work for its worthiness. The suggestion is that the night is a dangerous place, not only because of the increased potential of assault, but also because women themselves cannot handle this level of freedom without losing their virtuous natures and spotless reputations. In addition to accusations of sexual manipulation often levelled at ambitious and successful professional women from all fields, all call centre workers have to carry the burden of a suspect morality. Women’s choices to have fun then become irrelevant to the story. These stories tend to be about the loss of control over good women and, to a lesser extent, men as well. When women trespass the acceptable boundaries of time that demarcate day and night, and public and private, and begin to work at night, all kinds of anxieties emerge. One of the major fears associated with call centres is that women are potentially having too much of the ‘wrong’ kind of fun— the kind of fun that jeopardizes their reputations as good girls. Unfortunately, nobody seems to remember how hard and long BPO employees actually work for a living. The self-professed guardians of morality remain fixated on the possibility that ‘good’, middle-class call centre girls will acquire the ‘tainted reputations’ of call girls and bar dancers. The temporal boundaries of day and night are imposed as rigidly as those of private–public and are irrevocably linked to the duality of being respectable–unrespectable. Until all these boundaries are challenged together, certain spaces, places and times will continue to be off limits for women. Unless our effort to ‘reclaim the night’ can include all women of the night, these efforts are doomed to remain forever symbolic. Can we strike at the heart of middle-class morality and respectability to assert not only that the night belongs to us but also that we belong to the night? 20. Can Girls Buy Fun? Inside High Street Phoenix’s Spaghetti Kitchen, which stands under the shadow of a silent chimney of a forgotten mill, a boisterous ladies’ kitty party is underway. Laughter rises above the clink of glasses as iced tea and plates of mushroom risotto and pesto-stuffed ravioli make the rounds. The party could well be a prelude to a collective shopping spree. Outside the posh complex, merely a few yards away, stand the dilapidated chawls housing the families of mill workers. Some of the women from these chawls are also at the mall. They stand on the other side of the counter. Even as the textile mills transform into upmarket retail shops, multinational offices and high-rise housing, the older structures remain, ever-present reminders of a different city, another time. The swanky new edifices of Central Mumbai cannot completely transcend their past. Significant numbers of former mill workers still live in the area. Both the defunct textile mills and the residential chawls for the workers are located here. In these areas, the city of production and the city of consumption look each other in the face. In the master narrative of this city, malls have replaced mills as the desired markers of modernity. Within these spaces, it becomes possible to truly transcend the poverty, dirt and third worldness of the city by immersing oneself in the smells, textures and experiences of consumption that parallel those in first world cities. The former spaces of production must now be aestheticized, their original functions and inhabitants displaced. Where retained, as in the High Street Phoenix mall complex in Mumbai’s Lower Parel area, the empty shells of the original structures—with their large skylights, nineteenth-century cast-iron pillars, and towering chimneys—seek authenticity by invoking the nostalgia of a glorious industrial past. From the perspective of women’s access, one might be tempted to assume that this change is for the better. Mind-numbing manufacturing spaces dominated by sweaty male bodies have been replaced by hypnotic spaces of consumption inhabited by deodorized female bodies. So, do these seductive spaces live up to this image of inclusion for women or do they mask underlying inequities? Spaces of consumption are privately owned and their owners have the legal rights to control access. These are not public spaces. Access depends on class—whether you can afford, or at least look like you can afford, to consume. These spaces are thus accessible to only a small minority of women. They render invisible a large group of women and men, many of whom may be involved in the production of commodities which facilitates this consumption. During our research, we found women in the malls—strolling, talking animatedly, watching films, shopping, dressed to accentuate their position as early twenty-first century urban women in a global city. Not all women, however, are here to play; for many, these are spaces of work. If middle-and upper-middle-class women are in these private–public spaces as consumers, lower middle-class women enter these spaces as saleswomen and are thus introduced to global cultural practices of consumption. In many cases, both the shop assistants and the shoppers appear to be dressed similarly. The fact that the shopper confides her body-shape anxieties to the shop girl may add to this impression of equality, but the fact is that the shop girl cannot afford the dress the shopper is trying to fit into. The democratization of fashion begins in the dressing room, but ends at the cash counter. The saleswomen in the malls are inevitably dressed in western wear and often speak to customers in English. These young women and others like them inhabit almost schizophrenic worlds—living in their one-room homes and working in the posh several-thousandsquare-feet malls where they are required to display an accent and demeanour which reflects the class and status of the goods they sell. They are typically not very well paid, but must dress as their customers do. They must simultaneously embody an attitude of service to potential buyers, and exude cool reserve towards those who do not look like they can afford the goods. Shop assistants arrive at their jobs mostly in salwar-kameezes from which they change into the typical blouse with skirt or trousers uniform of the store for which they work. During conversations, some of them reveal that though their parents think it is acceptable for them to work as saleswomen, it is still not really acceptable for them to wear knee-length skirts outside their work (though jeans and trousers with untucked tops are acceptable). One woman told us, ‘It has not been easy for my parents to convince the neighbours that the work I do is respectable given that I reach home only after 10 p.m. every day.’ For most women, the late hours they work necessitates many negotiations. In another vein, in these former mill areas, where the class profile of the space is changing through gentrification, women’s movements, clothing and demeanour provide an important marker of these changes and the present sense of flux. In our research, women in the chawls spoke with pride about their daughters’ education and independence, but expressed a strong anxiety about the clothes they wore, the influence of the changing neighbourhood mores and the need to set boundaries. A woman in her forties argued, ‘It’s natural for young girls to want to look good but we cannot forget the rest of the world who love to talk.’ The malls are populated by upper-middle-class women consumers, many of whom wore their first pair of jeans as children and by these saleswomen, who are only just learning to wear them. In this space, the visible markers of appropriate womanhood— clothing, make-up, hair-styles—might appear similar, but they heighten the anxieties on both sides of class divide. Both the shoppers and the shop girls are at pains to distinguish themselves from each other, the former to underline class privilege and the latter to demonstrate that their clothing does not alter their ‘traditional’ values, most often to allay their families’ fears. In a context where consumption and fun have become inextricably linked, it might appear that buying is the only way to have fun. Spaces of consumption reinforce this image. The shiny glass and chrome interiors lend a bit of their glamour to all who tread their vitrified floors. Whether we are shop girls or shoppers, the airconditioned first-world-smelling spaces create the illusion that everyone can have their bit of fun. So long as the shop girl can smell the coffee, she can forget that her mill worker father is unemployed. So long as the shopper can shop her boredom away, she can forget that she quit the career track for motherhood. Instead of consuming the privatized charms of a mall, can we not imagine a city where we might encounter each other in a park or on the beach, without the divide of the shop counter, in quest of pleasures that cannot be bought? 21. Can Different Girls Think of Fun? The city is an endless obstacle course. Each disproportionately elevated and unevenly spaced pavement poses enormous challenges. All pot-holed streets are minefields to be negotiated. Every place with no ramp or elevator posts a ‘No Entry’ sign. All narrow public toilet cubicles (wherever available) are like taunting reminders of what you cannot use. If the city is unfriendly to its able-bodied women, it is much more hostile to its differently abled women, who are forced to wage a daily battle against it. Even simple acts of accessing public space for everyday tasks, which are taken for granted by other women, pose almost insurmountable odds for differently abled people, be they physically, visually or audio-challenged. A simple bus ride involves enormous strategizing for a visually challenged young working woman who travels from Parel to Fort every day. The lack of audio announcements in buses means she has to mentally count every stop until she arrives at her destination. A senior administrative officer who is wheelchair-bound finds most shops cramped and railway platforms unreachable. Even accessing an ATM machine to withdraw cash is often impossible. A visually challenged advocate finds the revolving doors at malls a real hazard.13 For a forty-something senior events manager at a city bookstore, who has cerebral palsy which severely affects her movement and speech, most places remain inaccessible. ‘My biggest frustration is that I can’t ‘walk’ the streets of Mumbai on my own,’ she says. When she visits a city like London, she can go almost everywhere—on the bus, to the museum or a movie theatre—totally on her own, using her motorized wheelchair. That is when she has fun, particularly since everything is accessible and she is not dependent on someone else being around to lift her up. ‘But I can’t do the same in Mumbai, my own city, and that is most disappointing,’ she says. She is aware that many other women like her do not even have access to these occasional pleasures since they cannot afford to travel to other differently-abled-friendlier cities. India is home to 70 million differently abled people.14 Most of them access public space against multiple odds. On the one hand, they battle an ignorant public unaware of how to include the differently abled. On the other, they confront insensitively designed spaces and transport systems which have never kept them in mind in the first place. It is a daily struggle to enter a building, cross a road, get onto a train, go to the market or just to watch a movie in a cinema hall. As one wheelchair-bound woman mentioned in an interview, ‘It’s almost impossible for me to participate in any activities in public space. I often find myself just being a spectator, always inside looking out.’15 While all differently abled people find accessibility to public space arduous, differently abled women have their own set of problems. Disabled men tend to have greater access to public space than disabled women. Often, for women, the battle for public access starts at home with parents and family members being overly protective and thus placing more restrictions on their movement. When they are out in public, they are compelled to depend on strangers for help, a situation fraught with anxiety, especially for women. Many differently abled women point out the discomfort in having to hold a strange man’s hand to cross a busy street or being carried by a man from the street level onto the high footpath, even if they are in a wheelchair. This is not only because of the fear of harassment, but also because physical contact with strangers is considered taboo for respectable women. To avoid accepting such help from strangers then, many disabled women will even avoid coming out of their homes. Disabled women are seen as being more vulnerable to harassment on the streets. One visually challenged woman told us that strangers often ask for personal details and make provocative comments, which she has learnt to ignore. But sexual harassment also depends on the nature of the disability. For those who are more visibly handicapped, being ignored is more of a reality. One woman with cerebral palsy said, ‘I am not even visible to them—people pretend I don’t exist. They don’t even talk to me, forget harassing me in any way.’ When every step you take has to be counted and even daily accessibility in the public space for work, study or routine chores is in serious question, it certainly kills any impulse to hang out in public for pleasure. ‘Fun? Where? Even when you go out do you see disabled peopled?’ asks an enraged thirty-two-year-old physically challenged woman. ‘How many parks and movie theatres are accessible to us? Even family outings become difficult if family members feel ashamed of having a disabled woman with them.’ It is not as if they do not yearn for a place to hang out in public. One young woman would like to go out with friends to bars in Mumbai, but almost all of them are too dark and constricted for her wheelchair. According to her, Mumbai’s lack of facilities for differently abled people has certainly affected her social life. Since she cannot navigate the city easily, she spends more time at home, mostly surfing the worldwide web on her computer. Newer spaces of consumption like malls and multiplexes have changed this to a certain extent because they are more accessible as many of them are efficaciously designed with ramps, elevators and wider passages. Certainly, design plays a role in improving access. The Persons with Disabilities (Equal Opportunity, Protection of Rights and Full Participation) Act, 1995, India, states that public buildings and transport systems have to be disabled friendly.16 Many of the architectural modifications required—a plank placed at an angle that works as a ramp, slightly bigger toilets to fit in wheelchairs, and so on—are not too expensive or difficult to implement. Still, they are rarely put in place and when they are, they are so badly designed that few would risk getting onto some of those ramps or using some of the sloppily planned toilets. Everything from banks to hospitals and transport services to hotels are built with scant regard to the disabled even though many of these simple design changes can benefit not just the handicapped but also older people, children and pregnant women. An activist with ADAPT (Able Disabled All People Together), a rights groups for differently abled people, is all for conducting access audits of all public spaces. She says, ‘It’s not just about adding ramps, it’s about having an attitude as a city that says differently abled persons belong here too.’ When she was studying in a premier South Mumbai college, the management sensitively put in ramps everywhere and arranged for her to use the elevator for classrooms on a higher floor. This made her feel welcome in that environment. Ironically, all the ramps were removed when she graduated. When infrastructural changes do take place, they can really change things around. In Bangalore, disability activists had an access ramp built in a park to encourage its usage by differently abled people. Initially, the park officials didn’t see the point of the ramp as they didn’t see any disabled people using the park. But once the ramp was installed and more disabled people went to the park, officials realized that necessity of good design coming first. Many disabled women feel most hurdles arise from biases rather than ‘actual’ obstacles. People often behave as if the differently abled somehow do not have the same desires for pleasure as themselves. It is as if their disability depersonalizes them. As one young woman put it, ‘People never think we live fully functional lives just like them. They make a major leap from “this person cannot see” to “this person cannot function”.’ This observation lies at the crux of why no efforts are made to make public space more accessible to the differently abled, especially women. Disabled women are excluded from public space not only because of their physical inability to access badly designed spaces, but also because of a larger ideology that does not recognize their very presence. Further, because they are seen as being more physically vulnerable, they are restricted even more than other women. On the one hand, they are seen as asexual in that their own desires are not accounted for, but on the other, they are also seen as sexually more vulnerable and as easy targets for public harassment and assault. It is difference and diversity that adds humaneness and empathy to our cities. Can we envisage a city where the differnetly abled can ‘walk’ unimpeded along with the other-abled and access the city to just hang out? 22. How Do only Girls Have Fun? The music is loud, the lighting dim, translucent tendrils of smoke arise from glowing cigarette ends as fruit juice and alcohol do the rounds, and the heady aroma of biryani spices fill the air. The party is in full swing—in one corner, a couple cuddles, in another, a vociferous argument on local politics breaks out; in the centre, a group swings wildly to the beat of the music. A regular Saturday night party in a suburban home you might think—except with one difference—this one is all-girls’ one, and this is no schoolgirl sleepover. Over the past few years, lesbian women have become more visible and articulate in the public sphere in Mumbai. This does not mean, however, that they have become more acceptable, especially as a group with a political agenda. For women who love women, any political claim to space till recently was complicated by the fact that legally Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code rendered all non-penovaginal sex illegal, both in public and in private. Although no woman was ever prosecuted under Section 377, it was used to threaten women in same-sex relationships. Living at the edge of the law implies disguising one’s sexual identity or at least some subterfuge, with the constant threat of harassment leading to a double discrimination against lesbian women in public space; both as women and as sexual minorities. Same-sex love in public might be tolerated in some upmarket spaces if it is not too overt, not too loud and if you follow the US army rule ‘not to ask and not to tell’. Or if you don’t mind seeking refuge in the sanctioned homo-sociality of being just good friends. Large cities like Mumbai do offer a certain kind of freedom that comes with anonymity—the possibility of getting lost in the crowd. But the other side of the anonymity coin is submerging your identity into that of the mainstream normative—in the case of lesbian women, this generally means passing off as heterosexual. This compulsion to be invisible and unobtrusive thus undermines lesbian women’s ability to mount political action on the basis of their gender and sexual identities. Despite the fact that it is difficult for lesbian women to demand public visibility, recently, there has been some media attention, especially in the shape of television talk shows that attempt to engage issues of sexual preference in a serious way. Prior to this, discussions on lesbianism were predominantly negative. For instance, cinema halls where the film Fire (1996), which sympathetically portrays a lesbian relationship between two sistersin-law, was released, met with vandalism. In Mumbai, the Shiv Sena went on the rampage, tearing down posters and threatening moviegoers. These protests received wide publicity and compelled lesbian women and other liberals to unite and protest. Even the film Girlfriend (2004), despite portraying the lesbian protagonist negatively as a victim of sexual abuse with homicidal tendencies, was subjected to acts of vandalism by right-wing groups. While large events like the Fire controversy have the effect of bringing the community together along with other progressive groups, everyday harassment is something that lesbian women learn to live with. Ironically, lesbian women record that often, it is all-women spaces that are the most hostile and fraught. While our research has shown that public transport in Mumbai, particularly local trains, greatly adds to women’s mobility and capacity to access public space, at the same time, it is far from being a space of pure camaraderie or freedom. Eunuchs are met with annoyance mixed with anxiety (though, unless they receive a great deal of support from each other, women will not actively demonstrate their hostility towards hijras whom they also fear). Women who dress and appear non-normative or inadequately feminine are also met with suspicion. Many women who choose a more assertive demeanour or favour a style of dressing perceived to be masculine are also the target of women commuters’ aggression and disdain. Transgender people and others who dress ambiguously are seen as a threat to the clear definition of both people and space. Looking different or dressing different always gets some response. One woman academic in her forties told us, ‘If I dress in a less feminine manner on any given day, then I have to be prepared to be in battle mode that day. Uncomfortable situations come in the shape of being asked to get off the ladies’ seats in buses, or being asked if I am a boy or a girl.’ There are some women who have stopped travelling by train because they find it too traumatic. Access for those who refuse to conform to established gender norms is thus deeply contested. Like trains, public toilets too are a vexed space. During a group discussion, one woman recounted how every time she goes into the women’s toilet, even in a five-star hotel, other women give her strange looks and she has to vociferously assert that, ‘I am a girl.’ Another time, she said, a woman told a group of lesbians, ‘I think you’ve got the wrong toilets.’ She felt that their attitude seemed to suggest, ‘How dare you masquerade, how dare you not fit in?’ Yet another woman pointed out that they got similar responses even from people who supported their political cause. Such people asked, ‘Why do you dress like cartoons in drag—how do you expect people to take you seriously?’ Finding flats in the city can also be difficult if women are openly lesbian. Given that India is a homo-social culture, women living with other women is not a cause for comment, but should they make their relationship clear, then landlords are not keen to have them. One couple told us of how once their relationship became known, the landlord threatened to lodge a complaint with the police against them unless they vacated the apartment. Despite the fact that many more women have come out in the open in recent years, lesbian relationships are fraught with everyday struggles for legitimacy. In Mumbai, like elsewhere, the internet has made it easier for lesbian women to network. With dating sites and e-groups, they now have a platform to communicate with each other, express their opinions, chat, joke and flirt. There are also many private parties where lesbian women gather to talk, connect and have a good time. Some lesbian women told us that in a suburb of the city, a group meets on Sundays once in three months at a lounge bar from 12 p.m. to 6 p.m. —with the complete support of the owner. But it is only at private parties and some private spaces of consumption that lesbian women interact as women who love women. Despite the presence of such spaces, they continue to find it difficult to meet others like them, especially since many are compelled to be silent about their sexual identity. In most other contexts, they are simply looked upon as women who are with other women. Often, for lesbian women too, the only ‘public’ spaces available are the spaces where they consume, especially if they belong to a certain class. However, there have been instances of hostility towards lesbian women in these spaces as well. In a group discussion, we were told of one case, where two women who were kissing in an upmarket bar were asked to leave and never return (though this was resolved later through negotiation). One woman pointed out that in the same bar, heterosexual couples kiss and make out all the time, without anyone batting an eyelid. Another woman recounted how she and a group of friends were taunted at an upmarket seafood restaurant while the management did little to stop it. In contrast, a third woman recollected that in a less upmarket bar, once a group of men who were staring and commenting loudly at them, were asked to leave. In both cases, the unfriendly attention they drew undermined the pleasure of the evening out. Relative to lesbian women, gay men in the city do have more space. The bar and cruising scene in public tends to be all-gay. There are an increasing number of gay parties in Mumbai and there are many celebrities who are openly out. Certain pubs and nightclubs have had gay parties and nights in the past. Clearly, then, even among a group of people who are all marginalized, men have more access to public space than women do. Many women sitting, walking, dining or dancing in a group will recollect having been asked (often in the politest of ways), ‘So you girls are on your own?’ This reflects a larger social attitude that assumes that women without men, even if they are in large groups, are ‘alone’. This is as much about the subtle imposition of the norm of heterosexuality (women belong with men) as it is about safety (women in public without men to legitimize them are unsafe). Are we doomed to forever smile back vacuously and disclaim being on our own? Will we as same-sex desiring women always have to hide our identities and negotiate for every inch of public space we occupy? Or can we imagine a world in which women can be in public on their own and still be seen as being together? 23. Do Old Girls Have Fun? O meri zohrajabeen, tujhe maloom nahi, tu abhi tak hai haseen aur mein jawaan … (Oh my beautiful one, you have no idea how attractive you still are, and how young I still am …) And so, every once in a while, an older woman is courted and teased in Bollywood style. She is supposed to be appreciative of the gesture, given that her grey hair doesn’t usually fetch her public compliments, and sometimes, she may even smile. But usually, she is just reminded of the fact that age does not bring immunity from public harassment. There are over six lakh senior citizens in Mumbai, about 81 million in the whole of India, according to HelpAge India. Senior citizens, officially persons over sixty years of age, are as much outsiders to the global vision of the city as other marginal citizens. In newspaper reportage, like women, older people only make news when they are attacked, murdered, abused or commit suicide. In India, the rhetoric around older people usually locates them in the family. The predominant concern is whether aging parents are being looked after by their offspring. In this process, like women, older people get infantilized. Moreover, in the new global city, older citizens, imagined to be unproductive, get further sidelined. This allows their everyday concerns such as levelled footpaths to walk on, adequate streetlights, preferential access to public transport or recreational spaces to be ignored. The fear many older people often have is that of losing balance and hurting themselves, much more than that of being assaulted. Interestingly, in the past year, disabled wheelchair access signs have sprung up at many bus stops, but there is no sign of actual slopes that might provide easier access for older people as well. An older man points out, ‘In a bus, though there are seats reserved for senior citizens, they are invariably occupied.’ One older woman adds, ‘Although there is a separate entrance for senior citizens, the bus never stops in the same place and you are often forced to take the back entrance.’ While buses might be difficult to negotiate, trains are near impossible, given the crowds. Added to this, public amenities like railway bridges and underpasses are also designed without acknowledging the particular needs of older citizens. It is not surprising that a city that ignores its 6 million poor has little thought to spare for its comparatively small population of senior citizens. Some gestures, however, have been made in the past few years to make the city more accessible to senior citizens. For instance, nana-nani parks were introduced in 1999 with the intention of providing space to seniors in the city. The presence of these parks legitimates the presence of older people and acknowledges their claim to public space. While most nana-nani parks in Mumbai are open to everyone, some are reserved for the use of seniors only such as at Girgaum Chowpatty and Shivaji Park. This creates a segregation that not all older people are comfortable with because it tends to make them feel isolated. As one grandmother puts it, ‘These parks are good, but I don’t go there because I don’t want to feel old. I want to go where the young people are. I won’t go there even when I get older.’ When boys become men, their space expands; their sphere of access spreads further and further away from home into the larger city, and their confidence grows simultaneously. However, when middle-aged men become old, their space contracts; they experience their body as less able, and their confidence diminishes. This puts them at a disadvantage relative to older women. Middleclass older men, used to unrestricted and unthinking access to public space when they were younger, are ill at ease in their new roles and often express anxieties such as losing their balance and falling down or being attacked. Older women, on the other hand, strategically access public space with skills honed over a lifetime. Furthermore, beyond a certain age, the fear of unsuitable alliances diminish, and with it, the need for familial and community control of women. Hence, for middle-aged and old women, notional access to space expands in comparison to that of girls and younger women. While older women acknowledge a sense of liberation from the relentless male gaze, many are still harassed, particularly by older men. As one sixty-something woman told us, ‘The young men often give up their seats for me, it’s the dirty old men who still leer.’ Older women might be nudged in a crowded bus, though they may not be a target of catcalls and lewd songs. More significantly, the memories of fear continue. One woman said, ‘I even dream about it. I’m out of the house and then I forget the way back home. A man is following me. It’s a dream that recurs.’ Moreover, age does not completely take away women’s need to manufacture purpose or legitimacy. Although reduced familial responsibilities facilitate greater access to public space, families still have to grant approval. It is still most respectable to go out in the company of one’s husband. Age does not bring freedom from the temporal boundaries of public space visibility. As one respondent put it, ‘The fear is that people will talk if they see me alone at this late hour.’ Older women sometimes seek legitimacy of access through bhajan mandalis or groups and other religious rituals. They may also join the local laughter club which can be rationalized in the name of health and spirituality—but this is about as far as it usually goes. Respectability continues to be all-important and activities cannot be articulated simply in terms of fun. In the proliferation of images of slim young women with their shopping bags that adorn a multitude of hoardings, older women are rendered invisible. The predominant images of older women come from soap operas where they are viewed in the one-dimensional binary of scheming mother-in-law/benevolent mother-in-law. Although there are the beginnings of a subtle pressure to look young and attractive (witness actor Hema Malini looking thinner and more glamourous than in her heyday), older women predominantly feel the pressure to dress and behave their age. As a retired teacher put it, ‘Even at my age, you do get looked at. But if you dress well, you hear comments like “Buddhi ghodi laal lagaam”, which means that my attire is inappropriate for an older woman.’ What is needed is a paradigm shift that sees older women as equally desirable and desiring citizens. This would mean acknowledging that older women, as much as anyone else, might want fun and excitement in their lives. In the popular imagination, good old girls are either beatific grannies or crotchety crones. In either case, it is assumed that their idea of fun is popping over to the neighbours for a cup of tea and a chat. We may have our adorable grandchildren, the daily soap opera and local gossip, but why should we also not ask for the same pleasures of the public that younger people desire? 24. Where Do Girls Have Fun? The gym is a good place to begin. You run on the state-of-the-art treadmill in an air-conditioned room filled with other sweaty bodies. You put your body through the paces as others do the same on steppers, spinners and cross-trainers. For variety, you may try the novel rock-climbing wall or the surya namaskars at the ashtanga yoga class next door. Or, like the many others around you, you may simply choose to plug in to your iPod and shut out the world outside. Literally shut it out, especially if you live in ‘gated communities’ such as Hiranandani Gardens in Powai or the Lokhandwala complex in Andheri (West) or even Dosti Acres in Wadala. These residential enclaves and others like them that are increasingly colonizing Mumbai, might have been built at different times—starting with the Lokhandwala complex in the 1980s on what was once swamp land, to the Hiranandani Gardens, built in the 1990s—but these are no simple housing colonies. The towering concrete and glass residential structures that crowd these enclaves, along with multi-tiered parking facilities, assorted commercial and entertainment establishments, and uniformed security guards at several points, make these complexes worlds in, and of themselves. Plenty of places then for a girl to have fun, you might think. Particularly when you do not have to deal with the squalid slums, mounds of garbage, the pot-holed municipality-controlled roads, the disorderly morchas and the noisy traffic jams that lie just outside the gates. But more than the noise and dirt, what gated residential enclaves are most effective in keeping out are the unwanted ‘others’. In fact, most of these enclaves are advertised precisely on these grounds, that is: come and live with ‘people like you’ who belong to the same class. Though Mumbai has always been a parochial city in terms of how people live in varied permutations and combinations of ghettos of intersecting class and community, the residential enclave is a completely new kind of ghetto. At Hiranandani Gardens in Powai, all security is private and domestic workers have entry passes. While the upper classes have lived in networks of affluence for a long time, what is new about these enclaves is that they are spatially laid out so that almost all activities can be accomplished within their boundaries. Many of the new constructions have a ‘model’ flat to show prospective buyers— complete with various fittings and accessories including furniture, crockery, bedspreads and curtains—to demonstrate the desired habitus of the occupants. Here, in a sense, class comes to stand in for community, where living with ‘others of one’s kind’ is an implicit guarantee of safety. But community, or at least cultural commonality, is also sometimes underwritten in the make-up of these gated communities. While all the gated communities might not be communally specific, it is not unheard of for many to have rules that prevent the sale of apartments to ‘non-vegetarians’. There are simultaneously colonies springing up which cater specifically to Muslims. The communal identity of the complex may not be overt, but is nonetheless marked, through the presence of a temple, a Jain derasar or a mosque in the premises. While no official will tell you so, housing agents will gently discourage you from approaching certain colonies if you don’t belong to the right community. The effective message of the gated communities is that you can ignore the larger city by creating your own sterilized bubble of paradise. Increasingly, instead of staking a claim to citizenship, the attitude is to shut out what you cannot change. What this means for the city is the creation of a group of people who apparently live in the city, but are impervious to many of its facets. Their own realities are generated within these spaces filled with consumer durables and accessories that look suspiciously alike in an effort to achieve a version of the model home they all saw when buying their flats. Their manufactured pleasures do not represent acts of citizenship, but are instead, acts of secession from it. Even if they belong to a class that often makes decisions about the city and its ‘vision’, within their cocooned ‘neighbourhoods’, they are consumers rather than citizens. So what are the pleasures available to women behind the closed gates, real or metaphorical? Many of these residential enclaves are fitted not just with housing units, but also schools, hospitals, hotels, landscaped gardens with jogging tracks, cricket pitches, kiddie sandpits, club houses with saunas, indulgent jacuzzi tubs and swimming pools, shopping centres, a variety of restaurants, pubs and all kinds of entertainment, including in some cases, miniature golf courses and go-karting tracks. Some also include office complexes. Sporting competitions are organized for residents, as are kitty clubs, special parties, fairs and fêtes. There are enough activities to keep you occupied 24/7. In fact, many advertisements for new housing colonies focus on the woman, showing her where and how she can shop, play, exercise, pray, send her kids to school, dine out—all this without stepping out of the compound; in other words, without ever having to deal with the messiness that is the city. Women then are encouraged to perceive these as ideal environments, to which they can return from work or even give up their jobs without the fear of boredom. ‘It’s so convenient to have the children’s school, my gym and the shopping centre in the same enclave where we live,’ says one stay-at-home mother. ‘This way, we don’t feel like we are always commuting. Everything we need is at hand and there’s no need to step out at all.’ Professional women find these spaces convenient for the services and anonymity they offer. The enclave itself is all new and lacks a history. People may assume a shared class, but know little of each other. The stereotypical nosy neighbour of the Bandra village or the Malabar Hill high-rise is unlikely to be found here, in effect almost eliminating the policing women may experience elsewhere. ‘It’s like a separate world,’ says one thirty-year-old woman who works in the television industry and has just bought a house in the Lokhandwala complex. As the numerous films that are shot here suggest, these enclaves approximate films sets where everything is staged and each player is acutely conscious of the need to perform her/his role. So long as one knows the script, and listens for the prompter cues if one forgets the lines, one can partake of the pleasures of this make-believe world. The biggest make-believe here is the pretence of a public space. For all the apparently public spaces here are, in effect, privatized spaces, regulated and controlled no less than the malls. In these spaces, one might be convinced that one may enjoy the pleasures of the public if one is willing to let someone else design the stage. In a world where women often perform a variety of personas—femininity, desirability, professionalism, super-motherhood—living on a stage where everyone is performing may even be a relief. But, at the same time, as a gated community resident, one is lulled into a false sense of actually having access to the public—to the neighbourhood pool, gym, walkway, coffee shop. In actuality, the pleasures we can partake of are quite limited. All that we do have access to is a world created inside boundary walls—a little bigger than our homes, a little larger than our building compounds, but much smaller than the city that we rightfully should have access to without restriction, and whose pleasures should be ours without question. Is it enough that a simulated city has been brought to our doorsteps suitably sanitized, stylized and deodorized? Or is this just a mirage distracting us from engaging fully with the real city and its public space? 25. Can Good Girls Have Fun? ‘I am a good girl, I am,’ says Eliza Dolittle to Henry Higgins in George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion, made even more famous by its cinematic avatar, My Fair Lady. By which, of course, Eliza was asserting that she was a flower girl not a sex worker, and demonstrating a compulsion to manufacture respectability that is universal to women across cultures and history, even though the idea of what constitutes a ‘good’ girl changes over time, space and culture. The question is: can good girls, the ones who desire to retain virtuous reputations, still have fun, take risks and perhaps even dream of loitering? We might answer by examining Chembur, a nondescript eastern suburb of the city. Chembur is verbal shorthand and could stand in for many other similar areas of the city such as Mulund or Vile Parle or Borivali or even Matunga—places that are middle-class bastions of a kind of self-important, complacent morality. Chembur is a middle-class suburb (though, of course, upper-class and lower-class people live here too) located on the Central (Harbour) railway line. The suburb is currently seeing a real estate boom, with a new mall and multiplex being built and is becoming more mixed in terms of its population composition. Its predominant populations are the Sindhis, the Punjabis, the Mangalorean Christians and South Indians dominated by the Tamil Brahmins. Then there are also the Gujaratis, the Maharashtrians, the Bengalis, and the Syrian Christians who are considerably fewer in number. Each of these communities has their own shifting definition of the ‘good girl’. At the risk of sounding simplistic and downright stereotypical, let us try to imagine what some of the definitions of these good girls might look like. This good girl does engineering, endeavours to visit the temple as regularly as possible, is firmly vegetarian and marries within her caste and outside her gotra, the mythical ancestral group. That good girl plays a musical instrument, preferably the piano; volunteers at the parish; is educated, but not too much; works, but not too late; and marries, preferably within the caste and community, hopefully within the religion and failing that, marries an educated man with ‘good prospects’. A third good girl knows she must marry early; prove her fertility as soon as possible, and live amicably and good-naturedly in a large joint family. A fourth good girl strives hard to meet parental expectations, works towards the job she simply must have; if her parents are liberal, she’s allowed to bring her boyfriends home and she can usually marry anyone educated, anyone but a Muslim or a dalit.17 These are stereotypes of possible women in Chembur that point to some codes of gendered conduct, but nonetheless, are as always partial descriptions. These are caricatures that do not always reveal the ways in which women in Mumbai, as elsewhere, negotiate with varying degrees of success, to redefine the term ‘good girl’ for themselves. The mothers of the good (and not-so-good) girls from various communities keep a watchful eye on all the would-be-good-girls. For instance, a young woman told us how indignant her aunt was when her male cousin’s girlfriend, a young woman from another community, held his hand in the aunt’s presence. This indignation is directed as much at the community, and its ‘different’ social mores, as at the young girl herself. Another woman said she had been attracted to the man who is now her husband under the mistaken assumption that he belonged to the same linguistic and caste community as she and was therefore ‘suitable’. By the time she discovered that he belonged to another community, she was already in love. Then, is it possible for good girls to have fun? In middle-class suburbs of the city, women negotiate the shifting definitions of good and bad women as best as they can, trying to be recognized as ‘good’ girls even as they seek to maximize access to the outside world. In some ways, this compels women to revise their definition of what constitutes fun. They negotiate where they can go and when. They cover up spaghetti tops with jackets and halters with scarves and travel in groups. Going out with other women whose parents are known to one’s own is often a strategy women use so that parents feel a sense of collective security in knowing their daughters are with each other—the respectability of each family endorsing that of the other. Instead of seeing this constant strategizing as a limitation on her movements, however, the good middle-class girl takes pride in her skill in ‘handling her family’, dodging the male gaze, and still managing to have fun. As one woman in her early twenties put it, ‘What my family doesn’t know, can’t hurt them. Besides, it’s not as if I’m doing something wrong.’ Sometimes, marriage expands access to public space since one now has a built-in ‘escort’ to go out with while retaining the aura of good girldom. Where couples live on their own in nuclear set-ups, and where women are financially independent, they often feel a sense of liberation at not being answerable to a parent. However, it is important to remember that despite the success with which women may or may not be able to negotiate their access to public space, this access is always conditional on their maintaining impeccable reputations. Such access is dependent on the largesse of the woman’s family and may be withdrawn at any time. It is a concession, not a right. Is the answer then to be ‘bad’ girls? Bad girls, however, have no protection—their families are embarrassed by them and anxious about their reputations. To be a bad girl might mean that one has wilful access to the public, but this also means limited capacity to bargain or negotiate for other rights. As one woman recounted, ‘I rebelled openly in my teens and my parents were always forbidding me from wearing these clothes or going to that place. It was a difficult time for them and me.’ Most women learn quickly that being ‘bad girls’ does not pay off. When it comes to accessing public space, in the short run, it certainly appears far more profitable to subtly manipulate the system rather than openly rebel against it. Given the multiple anxieties spawned by the perceived materialism and superficiality of globalization, good middle-class girls have become symbols of the resilience of Indian culture in withstanding the onslaught of ‘alien’ cultural ideas. Thus, despite the mushrooming of malls and multiplexes, respectable middle-class areas continue to bask in the image of being bastions of modesty and decency. They exult in the fact that, unlike in Bandra, women here do not move around the markets in shorts, sit by themselves in bars or smoke cigarettes in public. To the outsider, this might seem be mundane and unexceptional, but it represents the essence of solid urban Indian middle-classness—a middle-classness still defined by values of frugality, humility, honesty, hard work, education, family-centredness and always, always, respectability. And the middle-class good girl out there, but always within her limits, is ever-present to buttress this image. Here manipulation replaces protest, and strategizing stands in for rights. Rocking the respectability boat is too much effort. But will we always have to manoeuvre or wheedle our way out of the backdoor? Isn’t it time to claim the right to access public space through the front door? Imagining Utopias 26. Why Loiter? As we collectively produce our cities, so we collectively produce ourselves …. [If] we accept that ‘society is made and imagined’, then we can also believe that it can be ‘remade and reimagined’. —David Harvey (2000) ‘Why would you want to loiter?’ we are inevitably asked in tones that range from incomprehension to horror. As educated, employed, middle-class, urban Indian women (rather like the desirable-ought-to-be-good-little-women we write about), when we express a desire to seek pleasure in the city by loitering, it might seem strange to some. It might seem as though (a) as beneficiaries of the women’s movement, who have access to education, healthcare and employment, we are asking for too much, (b) given that most women in India don’t have access to even basic facilities, we are being frivolous, and (c) our desire to loiter is peculiar, for, in any case, loitering itself is an offensive activity. For some reason, nobody likes loitering. In fact, the state disapproves so much that it actually legislates against it. The Bombay Police Act, 1951, has a clause that reads: ‘Whoever is found between sunset and sunrise … laying or loitering in any street, yard or any other place … and without being able to give a satisfactory account of himself … shall on conviction, be punished …’ Lukkha, lafanga, vella, tapori, bekaar are words from various Indian languages; they are, without exception, uncomplimentary terms used to describe the act of loitering or the lack of demonstration of a visible purpose. When we think of people loitering in Mumbai, the image it conjures up is of crowded, messy and difficult-to-navigate street corners, the smell of cheap tobacco, the sight of paan stains, the sounds of boiling tea and unmodulated male voices. Etched into our imagination is the vision of the unwashed male masses, unmistakably lower class in attire and demeanour. This connection between loitering and lower-class men in some part explains why loitering is considered an anathema, particularly for women. Another reason, as we have argued earlier, includes the desire to pre-empt all risk, which at its most benevolent is intended to protect women, and at its worst, to control women’s sexuality by restricting movement. Other reasons, as we shall argue, are linked to the desirable image of the global city—ordered and controlled—and the exalted position accorded to productivity in this city. So why is it that we want to loiter and why do we think it will make a difference? What do we mean by loitering and why do we insist that it not be seen as an illegal act, but as something significant that celebrates the urban experience? Why do we exult in the disorder that loitering apparently creates and make the demand that everyone should be able to loiter, even those perceived to be ‘dangerous’? How will loitering through the physical occupation of space impact our cities and make them more liveable? In this final chapter, we will try and lay out why we think loitering holds the possibility of not just expanding women’s access to public space, but also of transforming women’s relationship to the city and creating a more inclusive urban environment.1 As we have argued so far, despite the fact that in contemporary Mumbai certain women are a desirable presence in the public, especially in their roles as professionals and consumers, women have only conditional access and not claim to city public spaces. Economic and political visibility may have brought increased access to public space, but this has not automatically translated into greater rights to public space for women. The Mumbai woman still has to demonstrate visible purpose and respectability each separate time she steps outdoors. This model of respectability, framed as it is in terms of a patriarchal sexual morality, automatically excludes those women who are deemed ‘unrespectable’, not only from staking any claim on public space, but also from the conditional protection conceded to ‘respectable’ women. Most discussions on women and public space tend to focus on questions of safety—and specifically, sexual safety—rather than those of access. Women’s exclusion from public space is closely connected to the presence of undesirable ‘others’ in the city. It is then, ostensibly, to protect women that others are barred from accessing it freely. These supposedly ‘dangerous’ others include lower-class and Muslim men, sex workers, hawkers and other marginal citizens. At any given time, the claims of one group can be held up against the other, ironically rendering both as outsiders to public space. In this tableau, no matter how it is played out, women always remain outsiders, cast either as vulnerable ‘good’ little women in need of rules and boundaries or as transgressive ‘predatory’ women who threaten social order. Across the city, different women with varied desires have to manoeuvre their way through a minefield of dos and don’ts to access their bit of pleasure in the public. In the long run, however, covert strategies can only take us so far. So long as women’s presence in the public space continues to be seen within the frame of public and private, and within the interwoven hierarchies of class, community and gender, an unconditional right to public space will remain a distant dream. If what we want eventually is unconditional access to public space based on articulated rights of citizenship, then we cannot shy away from making a political claim. It is to this end that we make a case for loitering as a fundamental act of claiming public space and ultimately, a more inclusive citizenship. We believe the right to loiter has the potential to change the terms of negotiation in city public spaces and creating the possibility of a radically altered city, not just for women, but for everyone. WHY LOITERING MIGHT WORK WHERE OTHER STRATEGIES FAIL Our desire to have all people loiter is not rooted in any altruism, but in the simple understanding that no one group can claim access for itself without claiming it for all others. The competing claims to public space of different groups are founded on the parochial and discriminatory classification of people into ‘desirable’ and ‘undesirable’ persons, and based on their being identified as male, female or transgender, rich or poor, upper or lower caste, young or old, Hindu or Muslim, Christian or Sikh, Jain, Buddhist or other, ablebodied or not, heterosexual, lesbian or gay. These oppositions underlie further divisions on the basis of occupation, geographical location, appearance and morality. In the battle for public space, these groups are artificially pitted against each other, cast them as either vulnerable or dangerous. What if all these people were out there? On the streets? Apparently doing nothing? Loitering is significant because it blurs these boundaries—the supposedly dangerous look less threatening, the ostensibly vulnerable don’t look helpless enough. What if there were mass loitering by hip collegians and sex workers, dalit professors and lesbian lawyers, nursing mothers and taporis, Muslim journalists and north Indian taxi drivers, visually-challenged management professionals and street hawkers, garbage collectors and heterosexual, brahmin bureaucrats. If these juxtapositions seem contrived, it is only because we have grown used to the hierarchies that divide us. They have become ‘normal’. This scenario might seem to be anarchic, but within this apparent chaos lies the possibility of imagining and creating a space without such hierarchies or boundaries.2 Loitering by diverse groups then has the capacity to decisively disrupt this taken-for-granted segregation of people into categories and makes these divisions not just redundant, but also ridiculous. If we accept that all people have the right to loiter, then cities will allow for a novel diversity that might be messy in appearance, but is actually comfortable because people’s claims to be in that space are secure. For women, such a space of ambiguity can be powerful. Since the very act of being in public without purpose is seen as unfeminine, loitering fundamentally subverts the performance of gender roles. It thwarts societal expectations and enables new ways of imagining our bodies in relation to public space. This can be very liberating since any performance of femininity is otherwise inadequate to counter their out-of-placeness.3 In a relative sense, the female body, which is expected to be located ‘properly’ in the private space of the home, has the greatest potential to disrupt the structures of power in public. The bubble of private respectability that women are expected to cloak themselves in cannot withstand the act of loitering because the two are based on contradictory imperatives—the former, one of maintaining privacy even in the public, and the latter, that of taking pleasure in the public, of celebrating the very publicness of public space. When women choose to take pleasure in public space, it challenges the division between private and public space, and therefore, between respectable and non-respectable women, thus undermining the illusion of privacy that women are expected to perform.4 The loiterer maps her own path, often errant, arbitrary, and circuitous, marking out a dynamic personal map of pleasure. The loiterer is independent, free-spirited and carries only the responsibility for herself. In this sense, loitering also has the potential to create a new sense of everyday embodiment—where one might stretch one’s body rather than contain it, where ones body language might express pleasure in public space rather than an awareness of its boundaries.5 This opens up a plethora of possibilities: imagine varied street corners full of women sitting around talking, strolling, feeding children, exchanging recipes and books, planning the neighbourhood festival or just indulging in some ‘time pass’. Imagine street corners full of young women watching the world go by as they sip tea and discuss politics, soap operas and the latest financial budget. Imagine street corners full of older women contemplating the state of the world and reminiscing about their lives. Imagine street corners full of female domestic workers planning their next strike for a raise in minimum wage. If one can imagine all of this, one can imagine a radically altered city. WHY IT’S WORTH THE RISK Loitering is perceived to be risky because it is often cast as dangerous and anti-social in some way. Interestingly, it is also illegal in many countries; good citizens are expected not to loiter, but to go about their work in an orderly fashion. Good citizens are then rewarded with the promise of protection in public space which is denied to those who loiter. This is even more stringently applicable to women who are forbidden from taking risks of any kind. When women demand the freedom to take risks instead of the guarantee of safety, we are implicitly rejecting this conditional protection in favour of the unqualified right to public space. We would like the right to choose to be able to go out at any time of the day or night or to choose to stay in. In some ways benevolent paternal protection is simple—it lays down the boundaries and all one has to do is skilfully negotiate them. Losing this protection, however conditional, will mean that one is compelled to take decisions and make choices whose outcomes we might have little control over. However, freedom from protection will also mean freedom, not from the male gaze or the threat of physical assault, but from having to consistently manufacture respectability in order to be worthy of protection. The right to risk is unconditional. The right to risk knows no temporality, no codes of conduct and needs no symbolic markers to define one’s worthiness. The right to risk chooses freedom over restrictions and seeks freedom from restrictions. We acknowledge explicitly that with freedom comes responsibility. The demand for the unconditional right to take risks in lieu of protection places the responsibility squarely on women. Our desire then is to replace the unchosen risk to reputation and the unwanted risk of loss of respectability with a chosen risk of engaging city spaces on our own terms. Yes, there is street harassment, and yes, there is violence against both women and men. The fear of violence in public space is legitimate and cannot be merely wished away. At no point are we ignoring or even minimizing the violence, both sexual and non-sexual, that might potentially take place in the public and lead to physical as well as psychological trauma. Even as we ask for women’s right to engage risk in public space, we do not disregard the responsibility of the state and its mechanisms of law and order in dealing with public violence. Instead, we suggest that they deal very firmly with the aggressors of that violence and not tie up the victims of violence in endless blame games, inane dress codes, and relentless moral policing. The woman who seeks the simple pleasure of a walk by the seaside at night is in no way responsible for an attack against her. In another world, this would not be a risk, but given that it is a risk in Mumbai, and in several other Indian cities, the least one can expect is unequivocal justice if one is assaulted. The least one can expect is that the assailant be punished without collateral emotional damage to the victim. The least one can expect is to not be held responsible for that violence.6 The least one can expect is an acknowledgement of one’s right to walk on the beach, stroll on the waterfront, laze in the park without question.7 At the same time, however, we also need to recognize another kind of risk: that of the loss of opportunity to engage city spaces and the loss of the experience of public spaces should women choose not to access public space more than minimally. By choosing not to access public space without purpose, women not only accept the gendered boundaries of public space, but actually reinforce them. This renders women forever outsiders to public space; always commuters, never possessors of public space. The right to risk is not merely abstract. From the perspective of the city, it must be mirrored in the provision of infrastructure. While the decision to take certain risks must be chosen, risks must not be thrust upon women by inadequate or miserly planning. Infrastructure is central to access. The state and the city’s role in the provision of infrastructure like public transport, public toilets and good lighting are integral to the success of the larger claim to public space. Public space, then, does not mean empty space devoid of infrastructure and facilities, but a space that is thoughtfully designed with the intention of maximizing access. Not just functional spaces like train compartments, bus stops and toilets, but also spaces of pleasure like parks and seaside promenades are significant to creating accessible cities. For it is in these spaces that the joy of being in and belonging to the city is shared and communicated. While we must lobby for an infrastructure that will make it possible for us to take risks as citizens, at the same time, the demand for infrastructure that reduces risks should not provide the grounds to indict those who choose to take other kinds of risks not dependent on infrastructure. The presence of well-lit streets in the city should not mean that women found in dark corners should be deemed unrespectable or blamed if they are attacked. Choosing to take risks in public space undermines a sexist structure where women’s virtue is prized over their desires or agency. Choosing risks foregrounds pleasure, making what is clearly a feminist claim to the city. WHY LOITERING IS FEMINIST Pleasure, in and of itself, is low on the list of priorities of not just city planners, but also feminists. Feminists are often wary of demanding pleasure as it might be seen as frivolous or worse irrelevant to a discussion on urbanism.8 Loitering then is not very likely to find a place in a feminist list of demands. The desire for pleasure, especially in a context where people are poor or face violence, is often seen as suspect. In keeping with this strategy, feminist engagements with city public spaces have focused on eliminating the risks of violence as far as possible. Many feminists fear that if pleasure gets on the agenda, women will lose the ground we won with so much effort and difficulty. However, the struggle against violence and the quest for pleasure cannot be separate things. The quest for pleasure actually strengthens our struggle against violence, framing it in the language of rights rather than protection.9 The ‘right to pleasure’ must always include the ‘right to live without violence’. The struggle against violence as an end in itself is fundamentally premised on exclusion and can only be maintained through violence, in that it tends to divide people into ‘us’ and ‘them’, and actually sanctions violence against ‘them’ in order to protect ‘us’. The quest for pleasure on the other hand, when framed in inclusive terms, does not divide people into aggressors and victims and is therefore non-divisive. We believe that in the twenty-first century, the only kind of feminism that is likely to be exciting is a feminism of inclusion. As feminists, who have benefited from the struggles of our fore-mothers —for the right to political representation, to education and economic participation—we stake our claim to take the struggle further. We seek to claim not just the right to work but the right to play—the right to unadulterated unsanctioned pleasure. Bringing pleasure into the centre of the discussion might also then be a viable strategy to make feminism relevant again. In the undergraduate courses and workshops we conduct, our final sessions always focus on imagining a utopia. Students read Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain’s Sultana’s Dream and are asked to imagine their own vision of a dream world for women.10 So far, each time, we have found ourselves facing a completely silent group. They cannot imagine another world. This alternately bewilders and depresses us —for being over a decade older than them, we still nurture fantasies of a utopian city.11 There is an increasing sense among upper-middle-class young people today that to seek utopia is naïve and unsophisticated, that in a global world, we may simply buy our personal utopias whether these are expensive real estate or designer shoes. Furthermore, gender-based utopias uncomfortably conjure up that most maligned of labels: feminist. This discomfort is rooted in a perception of feminism as somehow joyless. The terms of definition our undergraduate participants in workshops use are inevitably negative —‘man-hating’, ‘anti-beauty’, and ‘anti-family’. As feminists, we know these are simply not true. But at the same time, it is also not untrue that after decades of struggle, while many women can today compete with men in the workspace, when it comes to pleasure, the battle has barely begun. A discussion on pleasure is deeply relevant to contemporary feminism. When in these same classrooms we mention the possibility of loitering, the desire to hang out without purpose, the right to take risks, the young women suddenly sit up and begin to pay attention. They don’t think, even for a moment, that we are being frivolous or peculiar. And they certainly don’t think we are asking for too much. If we recognize the desire for pleasure as legitimate, it creates a space that is outside of consumption to discuss desire and pleasure. If we take pleasure seriously as a component of freedom and liberation, it allows us to engage head on with the aspirations of young urban middle-class women, who believe that gendered restrictions are irrelevant to them. WHY LOITERING SHOULD MATTER EVEN TO THOSE WHO ARE NOT FEMINISTS Pleasure is relevant not just to feminists, but to everybody who inhabits this city. Over the last decade, Mumbai has become a less safe city for women in people’s perception. In reality, the city has become unsafe not just for women, but for everyone. This loss of safety is integrally linked as much to the urban planning policies of the city, which exclude all those defined as outsiders, as it is to actual instances of violence. As historical evidence shows, attempts to cleanse and sanitize cities have often had the opposite effect, of making cities even more fraught, violent and unsafe.12 The global claims of Mumbai are still new and fragile, and, therefore, to be guarded zealously. One of the ways these claims are often buttressed is by a clear definition of spaces as being inside– outside, public–private, and recreational–commercial. Loitering disrupts this imagined order of the global city. The act of loitering, in its very lack of structure, renders a space simultaneously inside and outside, public and private, and recreational and commercial, producing a constant state of liminality or transition. The liminality (in-betweenness) of loitering is seen as an act of contamination, an act of defiling space. Loitering is a reminder of what is perceived as the lowest common denominator of the local and thus is a threat to the desired image of a global city. Loitering as an act is about the purposeless occupation of public space—something that precludes the possibility of creating sanitized homogenous spaces. It is precisely this ambiguity that makes loitering potentially liberating. Loitering mocks the authority of any one group of people to determine the future of the city by speaking with multiple visceral bodies and through the indeterminate nature of the identity of the loiterer. Loitering is also a threat to the desired visibility of capitalist consumption in that there is no recognizable product—if a beverage is being consumed, it is likely to be unbranded, roadside cutting chai (three-quarters of a cup of tea). Loitering is located firmly outside the global market of packaged consumer products. In a scenario where all modes of recreation and fun are increasingly being privatized and come with a price tag attached, loitering challenges the unspoken notion that only those who are can afford it are entitled to pleasure. Loitering also disrupts the image of the desirable productive body —taut, vigorous, purposeful—moving precisely towards the ‘greater global good’. In a time when the performance of a consumerist hyper-productivity is becoming deeply significant in globalaspirational Mumbai, the choice to demonstrate non-productivity can be profoundly unsettling. Loitering is a threat to the global order of production in that people are visibly doing nothing. Loitering can have no purpose other than pleasure. Since loitering is fundamentally a voluntary act undertaken for pure selfgratification, it is not forced and has no visible productivity. Thus, loitering as a right implicitly assumes that everyone has the right to pleasure. The presence of the loiterer ruptures the controlled sociocultural order of the global city by refusing to conform to desired forms of movement and location and instead, creating alternate maps of movement, and thus, new kinds of everyday interaction. It thwarts the desire for clean lines and structured spaces by inserting the ostensibly private into the apparently public. Loitering as a subversive activity, then, has the potential to raise questions not just of ‘desirable image’, but also of citizenship: Who owns the city? Who can access city public spaces as a right? WHY LOITERING IS CENTRAL TO CITIZENSHIP Access to public space often reflects a person’s location in the hierarchy of the city. The upper-class executive in his air-conditioned car may never actually access public space, but his right over it is unquestioned. And then there are those like migrant labourers, who have little choice but to be in public space, sometimes to even live in it, whose rights are easily revoked and sacrificed at the altar of safeguarding ‘law and order’. Our understanding of loitering in public space is based on the right of each individual, irrespective of their group affiliations, to take pleasure in the city—as an act of claim and belonging. This is, however, not a notion that is located in a crude understanding of capitalism where each individual maximizes her pleasure in the city leading to the greater happiness of society. When we ask to loiter, the intent is to rehabilitate this act of hanging out without purpose not just for women, but for all marginal groups. The celebration of loitering envisages an inclusive city where people have a right to city public spaces, creating the possibility for all to stake a claim, not just to the property they own, nor to use the ownership of property as grounds for being more equal citizens, but to claim undifferentiated rights to public space. From our perspective, citizenship of a city is a visceral thing—just as adult franchise marks in one tangible sense belonging to a nation, so we claim that the right to physically occupy city public spaces is a tangible sign of city-citizenship. We believe that for women to truly claim citizenship, we must be able to claim public spaces with our bodies, by writing our claim everyday through our movements.13 For women the right to loiter represents the possibility of redefining the terms of their access to public space, not as ‘dependents’ seeking patronage, but as citizens claiming their rights. Unlike dependents, citizens are recognized as contributing, productive partners and therefore, while they are subject to state law, are nonetheless able to claim unconditional rights based purely on the fact of their citizenship. This means that the state’s responsibility to protect its citizens’ right to be in public space must be independent of the individual citizen’s class, caste, religion, gender, age, sexualorientation, physical ability, clothing, behaviour and perceived morality. It is as much the responsibility of the state to protect the right of the streetwalker to public space as that of the upper-class corporate executive. Similarly, it is as much the responsibility of the state to protect the right of the migrant worker to public space as that of the middle-class woman homemaker. It is this unconditional access to public space that is fundamental to changing women’s relationship to the city. This will change not just women, but also the city transforming both in ways that we cannot even entirely imagine. It is only when the city belongs to everyone that it can ever belong to all women. The unconditional claim to public space will only be possible when all women and all men can walk the streets without being compelled to demonstrate purpose or respectability. Women’s access to public space is fundamentally linked to the access of all citizens. The litmus test of this right to public space is the right to loiter, especially for women across all classes. Loiter without purpose and meaning. Loiter without being asked what time of the day it is, why we are here, what we are wearing, and whom we are with. That is when we will truly belong to the city and the city to us. Notes PROLOGUE 1 The project produced a video documentary on women’s hostels in the city, titled Freedom before 11, directed by Radhika Menon and Roseanne Lobo in 2004, a documentary on public toilets titled Q2P directed by Paromita Vohra in 2006, and an audio documentary on college dress codes titled And then they came for my jeans … recorded by mass communications students of SIES College in 2005 under the supervision of Sameera Khan, Shilpa Phadke and Anita Kushwaha. The project also included a full-fledged travelling photography exhibition on women and public space titled City Limits, curated by Shilpa Phadke and Bishakha Datta, with four young photographers (Karan Arora, Neelam Ayare, Roshani Jadhav and Abhinandita Mathur) in partnership with Point of View, a women’s media collective in Mumbai (www.pointofview.org). CITY LIMITS 1. Why Mumbai? 1 The ridha is the distinctive style of veiling used by the Dawoodi Bohra Muslim community—a combination of a loose, long pastel-coloured skirt, a short frilly cape and a hood or bonnet covering the hair. 2 The population of the city under the jurisdiction of the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM) is 11.9 million. The population of the Mumbai Metropolitan region, which includes areas beyond Dahisar and Mulund (which are the boundaries of the MCGM jurisdiction) is 18.7 million. (Census of India, 2001, www.censusindia.net) For a discussion on Mumbai’s history, see Dossal (1991), Dwivedi and Mehrotra (1995), Mehta (2004), Tindall (1992). 3 For questions of women’s safety in public spaces of New Delhi, see Viswanath and Tandon Mehrotra (2007) and JAGORI (2006, 2007). 4 Ramabai Dongre, a Maharashtrian Brahmin woman, excelled in the scriptures and was the first Indian woman to be known as Pandita. She married a Bengali man of a lower caste than hers, an act considered sacrilegious for her time. Widowed shortly thereafter, she drew the ire of the community, including that of the male reformers, by continuing to write and speak in public and thus openly challenging the ideologies that would have her live the life of a social recluse. On converting to Christianity, Ramabai continued not only to attack patriarchal Hindu Brahmanism but also directing her razor-sharp mind towards challenging Christianity. Her first work titled The High Caste Hindu Woman, was published in 1888. Rakhmabai’s refusal to honour a marriage made when she was an adolescent and live with her husband caused no little uproar. Her husband’s petition to the Bombay High Court, for the restitution of his marital rights, provided fodder for a great deal of public debate on the questions of child marriage, education of women, custom and legal reform. Rakhmabai herself participated actively in this debate, particularly by writing two letters that were published by the Times of India on 26 June and 19 September 1885 under the pseudonym ‘Hindu Lady’ and later, a letter to the editor published on 9 April 1887, signed as herself. Rakhmabai signalled to the court her willingness to go to jail rather than live with her husband, an act that even today would be regarded as radical. Rakhmabai went on to train as a doctor in England and returned to work in Mumbai until her death in 1955 at the age of 91. For more on the writings and activism that challenged the relegation of women to the private sphere, see Chakravarti (1998), Chandra (1998), O’Hanlon (1994), Tharu and Lalitha (1991). 5 This ball-park figure is arrived at considering that approximately 15 to 20 per cent of the local train compartments are reserved for women and they tend to be almost as full as the general compartments at peak hours. Further, a small number of women also travel in the general compartment. 2. The Unbelongers 6 For a detailed discussion on cities and citizenship, see, amongst others, Anderson (1991), Mitchell (1995), Sennett (1994). 7 These comments were reportedly made by Shiv Sena’s Uddhav Thackeray. (‘Migrants are defaming city: Uddhav says Sena will not tolerate atrocities against women’, Daily News and Analysis, 5 January 2008). 8 In February 2008, Raj Thackeray, estranged nephew of Shiv Sena chief Bal Thackeray and leader of the Maharashtra Navnirman Sena (MNS) launched a particularly virulent attack on the city’s north Indian population. North Indian taxi drivers were physically attacked by MNS goons and their cabs damaged. A movie theatre showing a Bhojpuri film was vandalized. The attacks against lower-class and working-class north Indians particularly, continued for several days in Mumbai and also spread to other towns in Maharashtra with many north Indian migrant farm and industrial workers fleeing in terror from the townships of Nashik and Navi Mumbai. In April 2008, Raj Thackeray played the Marathi card with greater vehemence, asking industrialists in Maharashtra to reserve 80 per cent of jobs in their factories and offices for bhoomiputras or sons of the soil. Earlier in January 2008, Shiv Sena leader Bal Thackeray, in a long interview to his party’s newspaper, Saamna, had also raised the issue of a ‘permit system’ for all outsiders to live and work in Mumbai. Sporadic incidents of abuse—verbal as well as physical—on north Indian working-class men, recur in the city. See ‘Battleground: North Indians face attacks for second day, Mumbai shames nation’, Hindustan Times, Mumbai, 5 February 2008 ‘Sena wants Mumbai permit for “outsiders”’, Hindustan Times, Mumbai, 22 January 2008; ‘Amchi manoos, tumchi jobs: Raj Thackeray wants all corporates in state to employ 80% natives’, Times of India, Mumbai, 10 April 2008). 9 Some scholars have argued that Mumbai was a communally volatile city even before the 1992–93 riots; see for instance, Varshney (2002). For a detailed discussion on the impact of the 1992–93 riots on Mumbai, see Appadurai (2000), Chandavarkar (2004), Hansen (2001), Masselos (1994) and Robinson (2005), among others. 10 Historian Raj Chandavarkar (2004) suggests that the closure of the textile mills and the rise of communalism are inextricably linked. He argues that the marginalization of the poor is reflected in the ways in which the workers’ resistance was dealt with by the city’s ruling elites and points out that at the same time, the Shiv Sena’s explicitly communal agenda actively damaged the workers’ resistance and weakened communist trade unions. It is this communalization and marginalization of workers, he contends, that made the pogrom of 1992–93 against the Muslims possible. 11 As a metropolis, Bombay/Mumbai has long prided itself on its multi-ethnic and multilingual cosmopolitanism. According to census research figures, a significant 57.4 per cent of its 12 million inhabitants belong to non-Marathi linguistic groups, with Gujaratis accounting for more than 18 per cent. Further, Dalits account for little over 12 per cent and Muslims constitute around 17 per cent of the city’s population. These figures have been generated by the Centre for Research and Development (1995) and the District Census Handbook Greater Bombay (1996) [quoted in Vora and Palshikar (2003)]. It is important to note here that in such census classifications, it is normally assumed that Marathi-and Gujarati-speaking populations are Hindu, although there are also Marathi-and Gujarati-speaking Muslims and Christians who then are not enumerated as such. This reflects a larger trend where heterogeneity among the majority community is specified while minorities are viewed as homogenous. Similarly, Dalits are also a very heterogeneous group. 12 There has been a fair bit of scholarly research on the question of Mumbai’s lost cosmopolitanism. For an elucidation of this debate, see Appadurai (2000), Dossal (1991), Masselos (1991), Patel (2003) and Varma (2004). 13 Shree 420 (1955) was built around the dream of owning a small patch of the city. In Jagte Raho (1956), Raj Kapoor spends a night thirsting for water in a hostile city and when Nargis, in the form of a jogan, finally offers him water, it is as if an oblation was being offered to the thirsty, as if there was still hope. Navketan Studios crafted slick noir thrillers with its most saleable star, Dev Anand, as a denizen of the underbelly of the city. Through the Amitabh Bachchan-dominated 1970s, Vijay, the quintessential angry young man, rose from the slums (Deewaar (1975), Muqaddar ka Sikandar (1978), often falling in love with another outcaste, the dancing girl (Suhaag [1979], Muqaddar ka Sikandar), always cocking a snook at the rich. The city’s most famous anthem sung by Mohammed Rafi, ‘Aye dil hai mushkil jeena yahaan’ (Oh heart, how difficult it is to live here) from the Hindi movie CID (1956), picturized on Johnny Walker, expressed this ability to critique the city perfectly. ‘Beghar ko awaaraa yahaan kehete hans hans/Khud kaate gale sabke kahe isko business/Ik cheez ke hain kai naam yahaan’ (Laughingly, they call the homeless, vagrants/While themselves they cut the throats of all and call it business/One thing has many names here). Yet few remember that in reply to Rafi’s ‘Zara hat ke zara bach ke, yeh hai Bombay meri jaan’ (Be a little careful, this is Bombay, my dear), at the end of the song, Geeta Dutt crooned hopefully, ‘Aye dil hai aasaa jeena yahan, Suno mister, suno bandhu, yeh hai Bombay meri jaan’ (Oh heart, it is easy to live here, listen mister, listen friend, this is Bombay my dear). 14 Times of India (2007) for its ‘India Poised’ campaign. 15 Sharit Bhowmik (2003) assesses that Mumbai has roughly 2.5 lakh street hawkers, about 30 per cent of them being former workers of the erstwhile textile mills. Jonathan Anjaria (2006) argues that since the late 1990s, elite NGOs and residents’ associations have been actively promoting the idea that hawkers are to be blamed for many of the city’s public problems. 16 This report was brought out by the international consulting firm McKinsey for Bombay First, a corporate-funded lobby group. 17 This stereotype is based on the Muslim personal law in India, which allows Muslim men to have four wives. Thus, the common misperception is that Muslim men father many more children than Hindu men do. As per the Census of 2001, Hindus account for 80.5 per cent of all Indians, or 828 million while India’s Muslim community stands at 138 million, or 13.4 per cent of the total population. In recent years, Muslim fertility rates have fallen significantly. While the Total Fertility Rate (TFR) among Hindus fell from 3.3 in 1992–93 (National Family Health Survey [NFHS] I), to 2.8 in 1998–99 (NFHS II), the fall among Muslims was even more rapid: from a TFR of 4.4 in 1992–93 (NFHS I) to 3.6 in 1998–99 (NFHS II). (‘Religion and Fertility Behaviour: Canards and Facts’ by Rammanohar C. Reddy, Hindu, 10 November 2002). See www.infochangeindia.org/September 2004 and www.bbcnews.com, 8 September 2004; Indian Express, 7 September 2004; Asian Age, 7 September 2004) 18 By some estimates, Mumbai has the most heterogeneous grouping of Muslims amongst all cities in South Asia. Currently about 18.56 per cent or 2.2 million of Greater Mumbai’s nearly 12 million population is Muslim (Census of India, 2001). See http://www.censusindia.net/. Besides, the general doctrinal classification of Shia and Sunni (which can be further divided by particular schools of theology), the city’s Muslims can be categorized in several different ways by place of origin, language, occupation, class and caste. The major groups in the city are the Dawoodi Bohras, the Sulaimani Bohras, the Aga Khani Khojas, the Halai Memons, the Kutchie Memons, the Konkani Muslims, the north Indian Uttar Pradesh and Bihari Muslims, the Keralite Moplahs, the Deccanis and the Iranis. 19 In one case, the reporters Supriya Sharma and Rakesh Solanki (NDTV 24/7, 12 March 2004) were told: ‘We have decided that we will not allow flour mills, liquor shops, Muslims and fast food outlets.’ 20 Even prior to the riots, a sizeable percentage of Mumbai’s Muslims lived in community-based enclaves in areas such as Mohammed Ali Road, Bhendi Bazaar, Pydhonie, Dongri, Nagpada, Madanpura and Mahim. Poorer Muslims lived in the slums of Cheetah Camp (Deonar) and Behrampada (Bandra [East]). At the same time, many Muslims also lived in mixed areas of the city. However, after the riots, the city’s social geography underwent a radical change. Both Hindus and Muslims who lived in mixed areas, where they were in a minority, moved to neighbourhoods dominated by their own community. Many Muslims were compelled to move into the already dense Muslim-dominated neighbourhoods of south and Central Mumbai— Nagpada, Madanpura, Agripada and Bhendi Bazaar. Others moved outwards to Jogeshwari, Kurla, Malvani (in Malad) and Govandi. Middleclass Muslims were attracted to the Millat Nagar complex in Andheri (West) while poorer Muslims sought refuge in the Bharat Nagar slums in Bandra (East). Still others went to live in the extended suburbs of Mira Road in north-west Mumbai and Mumbra in Thane district. See Khan (2007), Robinson (2005). Furthermore, such community-specific ‘ghettoization’ now has legal sanction. In 2005, the Supreme Court of India upheld the formation of cooperative housing societies where membership is restricted to persons from the same caste or religion. In fact, in recent years, there has been an upsurge in exclusive community ghettos and only-vegetarian housing societies in Mumbai. In one case, residents of an ostensibly vegetarian building would spit at and throw pebbles on the patrons of a non-vegetarian restaurant in the same building, forcing it to close down. (Anuj Chopra, Tehelka, 17 September 2005, http://www.tehelka.com/story_main14.asp? filename=hub091705noentry_we.asp, accessed in July 2009). 21 Scholarship on women and nationalism examines how women’s location as bearers of tradition as well as primary biological and cultural reproducers of the nation makes them doubly marked in situations of national strife. They are simultaneously vulnerable targets for the ‘enemies’ of the nation, and objects of heightened protection/surveillance from within the community/nation itself. When communities are marginalized, it is women who are subject to most violence, not only by virtue of their community identity but also as a result of their gender. When women have to choose between community and gender identity, it is gender that is usually invisibilized. See the work of Enloe (1990), Kandiyoti (1991), Sarkar (2001), Verdery (1993), Walby (1992), Yuval-Davis (1997) and Yuval-Davis and Anthias (1989). 22 Debates on questions of gender in development point to the fact that when communities are deprived of resources, it is women who are the worst affected. Since women have the primary responsibility not only for domestic work involving child care, family health and food provision, but also the community management of housing and basic services, along with the generation of income through productive work, it is they who bear the burden of attempting to secure these services by other means. For an elucidation of these concerns in relation to development, see the work of Agarwal (1994), Kabeer (1995), Mies and Shiva (1993), Moser (1993). 3. Good Little Women 23 The complex world of these ‘ladies’ bars’ is skilfully invoked in two films, Mira Nair’s documentary India Cabaret (1984) and Madhur Bhandarkar’s feature film Chandni Bar (2001). In 2005, when dancing was banned in these bars by the Maharashtra state government, there were about 1,300 such bars which employed about 75,000 dancers in Mumbai (Flavia Agnes, India Together, 26 July 2006, http://www.indiatogether.org/manushi/issue149/bardance.htm, accessed in January 2007). Even before they were outlawed, several attempts had been made to restrict and regulate them. The bars were regularly raided for ‘illegal’ activity and the arrests made (usually on charges of obscenity) suggested that it was the bar dancers who were seen to be the morally and sexually disruptive elements in that space and in effect, the city at large. The dance bars and the dancers were perceived to be even more threatening because they operated at night, a time when the need to regulate both women and sexuality is stronger. Class politics are also obviously at play since when the dance bars were banned, no similar ban was imposed on dance performances in establishments of three-star and above categories, as well as gymkhanas and clubs, where the ostensible purpose was ‘promoting culture’ and ‘boosting tourism’. 24 See Phadke (2005a, 2007a). 25 In fact, it is poor women in large cities and young Muslim women who feel the most unsafe according to the Indian Express-CNN-IBN-CSDS State of the Nation Survey on Indian Women. The survey interviewed about 4,000 women in 160 locations in rural and urban India across twenty states of the country. About 68 per cent of poor women in metros and 61 per cent of young Muslim women in addition to 58 per cent single working women were reported as feeling most vulnerable to everyday routine violence (Indian Express, Mumbai, 24 January 2008). 26 In the struggle for gender justice it is assumed that because middle-class women have a comparatively good deal, they do not merit much attention. Unlike the feminist movement in the west which was accused of being white, middle-class and bourgeois, the women’s movement in India has always been sensitive to issues of class. Voices from within the movement and women’s studies have also self-consciously raised concerns about the legitimacy of urban middle-class women speaking for the poor or rural women. For instance, left parties have suggested that urban middle-class women in the ‘autonomous’ women’s movement could not possibly represent ‘Indian’ women and that the real role of feminists was to participate and raise questions from within mass organizations. These ideas have rendered feminist studies of middle-class women slightly suspect. See Phadke (2003, 2005b) for more on the women’s movement. For more about the middle-classes in India, see Varma (1998), Fernandes (2000), Phadke (2005b). 27 See Walkowitz (1992) and Wilson (1991). 28 Hindu nationalists today similarly see the family as a location of resistance where the woman becomes the crucial pivot that holds the family together. By identifying the nation as a family, the role of women in the public sphere is seen as an extension of their domestic duties. Women in the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) women’s wing, known as the Rashtriya Sevika Samiti, continue to identify themselves with the family to the extent that the first three heads of the Samiti (pramukh sanghchalikas) are known, not by a professional title as the first two leaders of the RSS are—Doctorji and Guruji (teacher)—but by names that are kinship markers: Mausiji (maternal aunt), Taiji (elder sister/aunt) and Ushatai (elder sister). As leaders and role models for the women of the Samiti, and the Hindu nation by extension, the pramukh sanghchalikas embody the notions of hegemonic femininity in the nationalist discourse. 29 These exercises titled ‘Putting People in Place’ and ‘Tracing People’s Path’ were conducted during a number of long courses and short workshops with college students in Mumbai during the years 2004–05 as part of the pedagogic initiatives of the Gender and Space project. The longer courses were held at the Department of Sociology, St Xavier’s College (August– September 2004), Sir J.J. College of Architecture (November 2004–March 2005), and the Department of History, St Xavier’s College (March–April 2005). The short workshops were conducted at Sir J.J. College of Architecture (July 2004), Majlis Legal Centre (June 2005), J.J. School of Applied Arts, Mumbai (August 2005), Bachelor of Mass Media, Wilson College (August 2005), Bachelor of Mass Media, SIES College (August 2005), L.S. Raheja Applied Arts (September 2005) and Russel Square International College (March 2006). For a detailed analysis of these exercises, see Ranade (2007). 30 That pleasure in public, particularly at night, is out of bounds for women unless they are willing to be branded as ‘unrespectable’ is clearly demonstrated in a HT-C Fore survey aimed at mapping the middle-class Indian male mindset, using a sample group of 500 men. The survey found that almost 46 per cent of men surveyed between the ages of twenty and forty-five, felt that women are ‘asking for trouble’ by going to a pub at night with friends, another 46 per cent said that if a woman in public swore at them, they would be tempted to get physical or aggressive. Two out of three men (64 per cent) felt that if they made friends with a woman ‘in a bar, they would think of a one-night stand’ (Hindustan Times, Mumbai, 6 January 2008). 31 A case in point is the assault on activist Madhusree Dutta by three policemen in 1990, at 2 a.m. at Borivili station, where she was buying biscuits and cigarettes. To begin with, the case of assault against the policemen was registered with some difficulty. During the trial that followed, Datta was asked what she was doing out late at night, referred to in the court as ‘Madhuri Dixit’ (a well known film star), and bombarded with irrelevant and humiliating questions. The farcical case and the media attention that followed made it clear that any woman out late at night, particularly buying cigarettes, was suspect (Vibhuti Patel, 1994). See also Svati P. Shah (2006) for a discussion on sex work visibility in Mumbai. 32 These notions of ‘polluted’ women and their capacity to adversely influence public spaces are neither new nor unique to the Indian context. In nineteenth-century Britain, for instance, legal measures were undertaken to control and police the sexual activity of ‘fallen women’, particularly in London. In her work on late Victorian London, Judith Walkowitz (1992) argues that by the 1840s, the streetwalker had become a source of considerable anxiety—simultaneously a source of disease and an object of pity. Official concern over prostitution as a dangerous sexual activity and a potential source of physical and moral pollution led to the passage of the first Contagious Diseases Act in 1864 (followed by the Acts of 1868 and 1869). The Act provided for the medical and police inspection of prostitutes in garrison towns and ports. The Act was repealed in 1886. Women’s restricted access to public space is thus connected to a notion of ‘defilability’ which suggests that women’s presence in certain privileged spaces, usually in public, may threaten the sanctity of these spaces. At the same time, women themselves face the threat of being defiled in public spaces, especially at particular times of the day (Phadke 2005a). In suggesting this we invoke the work of anthropologist Mary Douglas, Purity and Danger, where she explores the connection between the classification systems that structure a society and its prevalent notions of purity and pollution. Douglas also shows how pollution taboos play an essential role in reinscribing the defined boundaries of the community. In relation to public space this is reflected in the taboos that dictate the location of women’s bodies—the pure bodies of ‘good’ women, which are to be secured ‘inside’ to ensure their continued purity and the ‘polluted’ bodies of ‘bad’ women to be policed so that they do not contaminate either space or society. 33 See Phadke (2007b). 34 As reported in Indian Express, Mumbai Newsline, 13 March 2006/14 March 2006; Times of India, Mumbai, 14 March 2006. 35 It is estimated that about 75 per cent of all rapes take place within the family, as the then home minister Shivraj Patil told the Lok Sabha, with parents and close relatives often being perpetrators of the heinous crime (Times of India, 19 March 2008). 36 See Phadke (forthcoming). 4. Lines of Control 37 Foucault’s notion of ‘disciplining’ draws fundamentally on a conceptual prison type called the panopticon, proposed by political theorist Jeremy Bentham. The panopticon comprised a central tower and cells around it— from where the ‘watcher’ can see all the cells but prisoners can neither see him nor each other. Bentham argued that once the prisoners become aware of being watched, they internalize the omniscient gaze and don’t need to be actually watched anymore. Foucault’s analysis has been interestingly harnessed by several feminist scholars such as Susan Bordo, Jana Sawiki and Sandra Bartky, among others, to examine how particularly women’s bodies are disciplined. Bartky’s (1988) analysis of ways in which women’s bodies and faces are shaped and ornamented, in the context of western cultures, demonstrates eloquently how these ‘disciplines’ operate to normalize certain ways of being ‘women’ thus rendering other interpretations unviable and suspect, to say the least. She identifies three disciplinary practices which ‘produce a body which in gesture and appearance is recognizably feminine’. These include: those that aim to produce a body of a singular shape and size, those that work towards determining the gestures, postures and movements of this body, and those that dress up the body. Bartky suggests that modern disciplinary power regulates women without violence or public sanctions, by centring normative femininity in a woman’s body—specifically its assumed heterosexuality and appearance. Iris Marion Young, in her essay ‘Throwing like a Girl’(1990) argues that ways in which women use and look upon their bodies is distinct from the way men use theirs. While ‘the masculine body moves fluidly and confidently’, ‘the feminine body uses limited movements’ that is marked by an underconfidence in the capacity of her body and in an exaggerated fear of injuring it. Young argues, ‘Not only is there a typical style of throwing like a girl, but there is more or less a typical style of running like a girl, climbing like a girl, swinging like a girl, hitting like a girl … For many women as they move in a sport, a space surrounds us in imagination that we are not free to move beyond; the space available to our movement is a constricted space’ (146). 38 This is suggested by scholar Rosa Ainley (1998) who further argues that gendered space must be seen as a constant process of becoming. Here one might also invoke Judith Butler’s (1990) conception of gender as being a ‘regulatory fiction’ in society (Butler 1990). ‘Feminine’ and ‘masculine’ codes of behaviour have to then be relentlessly performed and regulated because anybody that attempts to transgress the boundaries of appropriateness threatens to disrupt this social order. 39 Historically, too, women have claimed public space at ritual celebrations. For instance, see Sennet’s (1992) description of the Adonia festival and Ehrenreich’s (2006) exploration of Maenadism, both in ancient Greece. Closer home, in Hindu mythology, the god Krishna is reputed to have charmed women into leaving their homes at night to find him. At the same time it must be noted that even within these spaces of ritualized celebration, there continues to be an insistence on women performing normative femininity. 40 See Phadke (2007a). 41 In 2006, Tamil Nadu’s Anna University imposed a dress code on 231 engineering colleges that fall under its purview, banning jeans, sleeveless tops, tee-shirts and tight-fitting clothes. The move was supported by players across the political spectrum—from the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) to the Periyarist Dravidar Kazhagam (PDK), the Paattali Makkal Katchi (PMK) and the Dalit Panthers of India (DPI). Around the same time, Orissa became the first state in the country to introduce a ‘uniform dress code’ for college students. Not only did the state ban college students from wearing sleeveless tops and tight jeans but they also instituted uniforms—which have been specified as salwar-kameez for girls and trousers and fullsleeved shirts for boys (Hindu, 6 September 2005). In Mumbai, the ViceChancellor of Mumbai University called a meeting of college principals in July 2005 to discuss a possible dress code for colleges though eventually nothing concrete materialized from it. For a discussion on dress codes, see Phadke and Khan, 2006. 42 Technically, fatwas are legal opinions to be issued only by a high priest; in reality they are being issued by all kinds of local maulvis. Women’s groups, such as Aawaaz-e-Niswaan, report that fatwas have been issued in various parts of Mumbai including Malvani (Malad), Jogeshwari (East) and Cheetah Camp on shunning dancing, singing, haldi/mehendi ceremonies, video shooting, and photography during wedding celebrations. In fact, some fatwas dictate that priests should not solemnize such ‘joyful’ weddings. If a family defies the fatwa then the priest is required not issue the nikahnama (marriage certificate) and the local masjid is directed not to bury the dead from that family. 5. Consuming Femininity 43 Discussions around consumption are often polarized between a defence of its pleasures and a critical assessment of its capacity of co-option. Some feminist scholars in the 1990s have focused on women’s agency and the pleasure in consumption, a pleasure that was sometimes read to have sexual overtones that might transgress defined boundaries of appropriate feminine behaviour. What these arguments suggest is that women’s access to public space and participation in consumption should be seen outside the discourses of capitalist oppression and ‘false consciousness’. Others argue that if these mall spaces are not spaces of false consciousness, and we do not believe they are, nor are they spaces of unmitigated agency. For a complex discussion of women, shopping and consumption, see Bowlby (2001), Friedberg (1993), Domosh and Seager (2001), McRobbie (1997), Morris (2000), Pollock (1988), Radner (1999), Walkowitz (1992), Wilson (2001), Wolff (1985). 44 We use ‘habitus’ as suggested by Pierre Bourdieu to refer to a socialized subjectivity, a way of theorizing the socially produced self and of understanding how social relations become constituted within the self, but also how the self is constitutive of social relations. Though for our purposes we refer to ‘habitus’ in relation to the body, the term extends beyond embodiments to include attitudes and tastes as well as often carrying with it the weight of individual and collective history. 45 See Phadke (2005a). 46 The new spaces of consumption, while problematic in themselves, are also not entirely unthreatened. Chennai, for instance, has seen the rise of a debate around concerns of couples kissing on dance floors in a discotheque and of women drinking at a fashion show. This has led to a discussion on the purity of Tamil culture and the role of women within it. This is interesting given that these are once again the spaces marked as transnational where ‘modernity’ is constructed and demonstrated (Swati Das, ‘The Moral of the Policing Story’, Times of India, 7 October 2005). More recently in January 2009, women eating lunch at a pub in Mangalore were attacked and beaten by activists belonging to the Sri Ram Sene. This was done on the grounds that ‘pub culture’ was indecent and un-Indian and a corrupting and immoral influence on Indian women. Undeterred by subsequent police action against him, the Sene chief, Pramod Muthalik, announced a protest against those celebrating Valentine’s Day, saying that boys and girls found together on that day would be forcibly married off. (‘Will Marry-Off Dating Couples on V-Day: Muthalik’, 5 February 2009, http://news.outlookindia.com/item.aspx?653467, accessed in August 2009) 47 Hindi films, particularly those of the Karan Johar variety, specialize in showing women how to play the sexy as well as virtuous game. Thus, before marriage a heroine is often shown wearing ‘sexy’ (see-through, halter, short, tight) western outfits but once married, in post-marriage scenes she is likely to be seen wearing traditional Indian saris with heavy brocade borders and pallus that can easily slip over the head. Similar is the case in Ekta Kapoor’s ‘K’ serials. Here, the only woman who can wear daring sexy outfits both before and after is the ‘vamp’, the house-breaker, the ‘unwomanly’ woman. 48 Daily News and Analysis, Mumbai, 31 May 2006 and June 2006 6. Narrating Danger 49 ‘Shame old story’, Hindustan Times, 2 January 2008. 50 ‘D.N. Jadhav’s faux pas’ and ‘Outrage’, Hindustan Times, Mumbai, 3 January 2008. 51 When the Times of India, Mumbai, 4 January 2008 ran a half-page story asking if Mumbai was becoming increasingly unsafe for women, almost 85 per cent of their readers said ‘yes’ but surprisingly most readers blamed the women for this. When women are held responsible for violence, this reduces not just access to public space but even the potential to seek legitimate access. Some responses to the Times of India survey were: ‘Everything comes with a price tag. If you want to enjoy clubbing at late night (sic) and stroll in the streets of Mumbai as if its Switzerland you can’t expect people to welcome you with flowers on the roads. If you have guts to handle the consequences then dare to party late nights.’ —Raj ‘Women are fighting for their freedom, what kind of freedom do they want? They come out on the streets half dressed at midnight and they want to walk freely. Women are equally to blame in these situations … they should bring about changes in their lifestyle.’—Venkat ‘I am deeply saddened but how could they be so empty-headed to go out at 1.45 am in such a crowd? Crazy women! What were they thinking, that people would come to protect them and bring them home safe? I must say that they paid for their foolishness and arrogance.’ —S. Moosa ‘Not only Mumbai, other cities too are becoming unsafe. But the people responsible for this are girls themselves. Why should they roam around at night? Can’t they celebrate at home? And what kind of dresses were they wearing? … I hope other girls will learn a lesson from this.’—Prakruthi 52 Women in the city are well aware of how little the police are vested in ensuring that their right to be in public space is protected. Everyday harassment in public space—streets, buses, trains, theatres, markets—is rarely reported by women to the police. This is not surprising because when women do try to report sexual harassment, they meet with little success. The police often refuse to register cases, downplay their importance and fob them off with complaint notes that have no legal standing. One woman told a newspaper reporter about an incident where she was chased by a group of men in a car from Matunga to J.J. flyover when she was driving home alone late at night. She stopped at a police check-post for help but the policemen on duty told her that it was not their job to help her. Eventually, she waited at the chowki till a friend came and picked her up. Another woman who registered a complaint about harassment by a man in the ladies’ compartment of the local train found the perpetrator at her door. The police had given him her address! Given these instances, it is not surprising that for most women, going to the police is often the last resort. Most women, when asked how they deal with sexual harassment on the streets, responded that they fight their own battles (Hindustan Times, 4 January 2008). Interestingly, the Mumbai suburban railways received more than 1,000 complaints of sexual harassment and molestation from women in 2007 (Hindustan Times, 5 January 2008). This is not to suggest that the Mumbai police are incapable of providing effective policing. Mumbai police’s strong campaign against drunk driving that began in 2007, managed to substantially cut down on the number of drunken driving accidents in the city. In fact, it has successfully created fear for the law among those who drink and drive. In 2008, the Mumbai police started a helpline for women, with the help of some women’s groups, on the number 103. However, this effort is currently not accompanied by a strong campaign against sexual harassment. 53 Rosa Ainley (1998) for instance points out that perceived threats to safety are different from, although not necessarily less harmful than, real threats. ‘Safety’ debates, she argues, ‘respond to the public’s perception of danger, rather than the likelihood of danger itself’ (94). This is the model used in understanding danger to women—the idea that danger is out there. See also the work of Andrews (2000), Garber (2000), Grosz (1995), McDowell (1999), Massey (1994), Parsons (2000), Rose (1999), Walkowitz (1992) and Wilson (1991). 54 As a somewhat tangential, but nonetheless significant aside, it is important to note that while women appear frequently as the victims of violence in news reports, they are conspicuously absent in other kinds of reports, sociopolitical or economic. Thornham (2007) notes that the 2005 Global Media Monitoring Project, the third such monitoring effort, analysed and compared data from seventy-six countries covering a total of 12,893 news stories in newspapers, and on television and radio. The report concluded that women are dramatically under-represented in the news. ‘In stories on politics and government only 14 per cent of news subjects are women; and in economic and business news only 20 per cent … As victims of war, disaster or crime they out-number men two to one’ (86–87). 55 According to this article, 86 per cent women in Delhi don’t feel safe, and every third woman knows at least one rape/molestation victim, according to a recent C-voter survey conducted after the capital witnessed a spate of rape cases in public places. According to Mumbai police records (2001 to July 2002), the city has seen 306 cases of eve teasing, 243 cases of molestation and 229 cases of rape. Chennai, once considered safe for women, now records a figure of 600 cases of crime against women in the last year. Characteristically, Delhi records the highest number of rape cases among the metros: 447 in 2000, 380 in 2001 and 299 till July 2002 as against Mumbai’s 124 in 2000 and 127 in 2001, which ranks second on this list. Gang rapes accounted for 8 per cent cases in Delhi and 57 per cent victims were in the age group of 0–16. The article goes on to suggest that even the cities of Bangalore and Kolkata do not guarantee safety for women (Times of India, 25 August 2002). 56 This report profiled the incident of Amin Patil shooting Muhammad Ali Umar Sheikh for allegedly harassing his wife and sister-in-law. The report focused on the increasing incidents of ‘eve teasing in the city that never sleeps’ (Sunday Express, 28 March 2004). 57 According to this report, a twenty-three-year-old model tried to complain to the constable on duty only to find that he refused to take her complaint as he was about to sign-off duty (Mumbai Newsline, Indian Express, 23 July 2004). 58 This article profiled the murder of a young BPO employee in Bangalore by the driver of the vehicle (Times of India, 17 December 2005). 59 On 30 January 2004 at 10.05 p.m., an unidentified youth hurled acid at the first class ladies’ compartment. Three women and a man suffered serious burns. This was in a Malad-bound local train between Bandra and Khar railway stations. The victims suffered about 20–25 percent burns on their face, neck and arms (Mid-Day, 6 February 2004). 60 According to the Indian government’s National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), the number of crimes against women in India (or at least the reportage of crimes against women) has increased continuously over the last five years. In 2007, about 1,85,312 incidents of crimes against women were reported in India compared to 1,64,765 in 2006, an increase of 12.5 per cent. Even a quick analysis of these statistics shows that crimes against women in the private space of the home have increased the most. In 2007, about 75,930 women became victims of torture and cruelty by their husbands and in-laws, accounting for the highest number of crimes against women. This was in addition to the 8,093 dowry deaths recorded nationally in 2007. In comparison, public violence against women in 2007 included 20,737 reported rape cases (and these included incest cases which would be categorized as private violence) as well as 38,734 molestation cases, 10,950 cases of sexual harassment and sixty-one cases of importation of girls. See http://ncrb.nic.in/ A news report commenting on this said, ‘As perverse as it may sound adult women are probably safer on Mumbai’s streets than in their homes’ (Daily News and Analysis, Mumbai, 24 March 2007). 61 Saamna, 25 April 2005. 62 This report appearing in the months following the rape of a college girl at Marine Drive in April 2005, talks of the plan by the University of Mumbai to institute a dress code that would ban mini-skirts, tight tops and shorts, apparently under the assumption that this will help prevent rape (Indian Express, 23 June 2005). 63 Indian Express, Express Newsline, 25 April 2005. 64 ‘Why was she with six men that night?’ by Divyesh Singh and Menaka Rao, DNA, 21 April 2009 (http://www.dnaindia.com/report.asp?newsid=1249292, accessed in April 2009). The same newspaper also had ‘Is it right to blame rape victims for the attacks?’ as a topic of ‘debate’ for the ‘Speak Up’ column, DNA, 22 April 2009 (http://www.dnaindia.com/report.asp? newsid=1249873, accessed in April 2009). 7. Courting Risk 65 In the 1980s, the Shah Bano court case and Roop Kanwar’s alleged sati opened up a Pandora’s box of divisiveness in the women’s movement in India, highlighting cultural, religious and communitarian identities. The events of the 1980s and early 1990s saw the political rise of the Hindu rightwing and concomitantly the appropriation of apparently ‘feminist’ positions by the Hindu right-wing. These were couched in terms of questions like: who constitutes the ‘real’ Indian woman? The Shah Bano case provided the first major jolt to the women’s movement. Shah Bano, a sixty-two-year old Muslim woman, appealed to the courts to claim maintenance from her husband, who had divorced her using the provision of triple talaq. In April 1985, the Supreme Court ruled that Shah Bano was entitled to maintenance by her divorced husband under Section 125 of the Criminal Procedures Code asserting that it transcended the personal laws of any religious community. The court was also critical of the way women have been traditionally treated unjustly and cited examples of Manu and the Prophet and urged the government to frame a common civil code. While Hindu right-wing organizations celebrated the judgement, as it seemed to endorse their position that Islam is inherently regressive, conservative Muslim bodies argued that the judgement was an attack on their religious rights and demanded that it be reviewed and that Muslims be excluded from Section 125. In 1986, the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Bill was introduced in Parliament which excluded divorced Muslim women from the purview of Section 125. The Bill was widely protested against by various women’s groups but unlike earlier joint campaigns against rape or dowry, this case led to a fragmentation of the front into various autonomous or religious groups. The issue of the Uniform Civil Code continues to be a contentious issue in the women’s movement as feminists who demand it to ensure the rights of all women, find themselves uncomfortably on the same side as the Hindu rightwing whose position they otherwise oppose. In September 1987, Roop Kanwar, a young eighteen-year-old woman, was burnt to death on her husband’s funeral pyre in Deorala, a village in Rajasthan, in the presence of a crowd of several thousands of people. The huge public outcry that followed this sati on the part of both those who opposed it as well as those who supported it became an issue of tradition versus modernity and most importantly, an issue of the cultural right of the Rajput people to preserve their identity. Feminists protesting against sati were seen as westernized, having lost touch and connection with their cultural roots and therefore not in a position to mediate in the issue. The labels of ‘westernized’ and ‘elitist’ were once again revived and the notion of the real Indian woman was created: traditional and culturally Hindu. Complicating this, were arguments framing sati within the notion of female subjectivity and questions of voluntary sati. Countering the fact that anti-sati activists phrased sati squarely as murder, it was argued that to posit the sati as inexorably a victim would only render her void of any function or agency (Sunder Rajan, 1993). However another position suggested that the attempt to separate and reify women’s agency and complicity and to represent violence as female agency is central to the production and reproduction of ideologies and beliefs glorifying and normalizing the sati (Vaid and Sangari, 1991). 66 The women’s movement has more recently also had to contend with women’s role as perpetrators of violence in the same riots and pogroms. Women have actively participated in riots, for instance in Bhagalpur in 1989, in Ahmedabad in 1990, in Surat in 1992 and in the tearing down of the Babri masjid (Tharu and Niranjana, 1999). In the Gujarat riots of 2002, the presence of women rioters was highlighted by the media as well. See in particular, the extensive work of historian Tanika Sarkar. 67 In a variety of places and contexts, women’s groups have sought to assert the right to be out at night without purpose in ‘Reclaim the Night’ protest marches. The first twentieth-century ‘Reclaim the Night’ rally took place in Rome in 1976, as a reaction to reported rapes reaching ‘astronomical’ figures (16,000 per annum). Around 10,000 women and children marched through the centre of the city. This was followed by similar marches in West Germany (1977). Women there demanded, ‘The right to move freely in their communities at day and night without harassment and sexual assault’. ‘Reclaim the Night’ marches were also initiated in England in 1977 by women in Leeds in response to the ‘Ripper Murders’. Angry at advice to stay indoors since the last ‘Ripper’ killing, they marched with torches through the town. ‘Take Back the Night’ marches in the USA were first held in 1978. In San Francisco, over 5,000 women from thirty states marched through the red-light district. These organized protests developed into campaigns such as ‘Women Against Violence Against Women’ (Herstory of Reclaim the Night, www.isis.aust.com/rtn/herstory.html, accessed in August 2008). Elizabeth Wilson (1991) argues that the goal of ‘Take back the Night’ is to reorder the city from a place where women are compelled to face ‘danger without pleasure, safety without stimulation, monumentality without diversity’ to one where inclusion rather than exclusion is the basic premise. Nancy Duncan (1996) suggests that the slogan is not a call to disregard personal safety but ‘to transform public spaces and make them safe and accessible to everyone at night as well as during the day’ (p.132, quoted in Don Mitchell [2000]). 68 On 2 July 2009, the Delhi High Court struck down the provision of Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, which criminalized consensual sexual acts of adults in private, holding that it violated the fundamental rights of life and liberty and the right to equality as guaranteed in the Constitution. Though celebrated by the media, the battle for equal rights of the queer community is far from over. 69 The French word, ‘flâneur’, suggests a stroller, idler, walker. In nineteenthcentury Paris, the flâneur is assumed to be a wealthy, educated man of leisure who could stroll the streets and arcades without being questioned; as someone who wanders the streets as an abstract and detached observer. He ‘looks’ at people, rather than the other way around, and assumes to understand them and to comment on them. Several writers and thinkers have reflected on the idea of flânerie, seeking to understand questions of location, identity, class and gender. Walter Benjamin, reflecting on Baudelaire, traces the flâneur from the pre-Haussmannian Paris through the creation of Haussmann’s boulevards and the beginnings of department stores, suggesting implicitly a linkage to an intensifying process of commodification. Donald (1999), reflecting on Benjamin in turn, points out that the flâneur ‘embodies a certain perspective on, or experience of, urban space and the metropolitan crowd’. The question for us is: does the female flâneur, the flâneuse exist? Doreen Massey (1994) suggests that the notion of a flâneuse is impossible because of the uni-directionality of the gaze. Flâneurs are the observers rather than the observed. It could be argued that these new public spaces of the department store and the cinema created possibilities for women to appear safely and respectably in public by reconfiguring the boundaries of outside/inside and public/private (Donald, 1999, p. 49). Similarly, in Britain, by the 1860s some restaurants, tea-rooms and department stores began to offer facilities exclusively for women, thus transforming middle-and lower-middle class women’s experience of public life (Wilson, 2001, p. 81). Janet Wolff (1990), however, suggests that women were almost completely excluded from the public sphere. She writes: ‘The public world of work, city life, bars, and cafés was barred to the respectable woman.’ Elizabeth Wilson (2001) argues that while in some ways the flâneur ‘represents men’s visual and voyeuristic mastery over women’ (p. 78–79), at the same time she believes that this does not completely preclude the possibility of a female flâneur. Linked to the questions of who can be the flâneur/flâneuse are the many complex and pressing questions of citizenship. In this context it is important to negotiate with the authorial dimensions of the act of flânerie and what it may signify in terms of a ‘gaze’ that reflects and reinforces the power structures of society, which define not only who has access to public spaces and how, but also who is allowed to represent them and thereby shape the discourse of urban living. For instance, Helen Scalway (2001) in a very exciting way, attempts to explore the complexity of being a woman drifter, a flâneuse in London. Scalway goes provides a nuanced account of a search for a space in the city, a quest for a fuller citizenship. She writes: ‘Ultimately, then the would-be city drifter in the feminine mode finds herself in a position where flânerie in its inherently territorial and controlling meanings, is neither possible nor desirable. Indeed it is only in developing practices of counterflânerie that the streets of the multi-cultural millennial city may ever hold space for all its users. This is walking which is about negotiation and regard for the Other: the street where relationship is possible: citizenship.’ Her vision of ‘regard’ for the ‘Other’ is crucial to the creation of city spaces which allow for multiple renditions and interpretations of space and flânerie and allow for a meaningful citizenship to develop. 70 See Phadke (2007a). 71 See Phadke (forthcoming). 72 See Phadke (forthcoming). 73 In relation to questions of sexual pleasure, anthropologist Carole Vance (1984) has argued that feminism’s success in bringing sexual violence into the public had also had the unintended consequence of suggesting that women are less sexually safe than ever and that ‘discussions and explorations of pleasure are better deferred to a safer time’ (6). She suggests that feminists were easily intimidated into believing that their own pleasure was selfish and that it was illegitimate to talk of sexual pleasure (until such time that sexual violence could be eliminated). She argues that such a time will never be and that we need to talk of sexual pleasure even as we battle against sexual violence and that these two projects are by no means mutually exclusive. Using this line of thinking, we would argue that we cannot postpone thinking about the pleasures of courting risk—the pleasures of walking the streets viscerally and writing the city with our bodies. EVERYDAY SPACES 8. Public Space 1 It is also important to clarify that public space is only a part of the larger construct of public sphere. Public sphere includes not only public spaces but also public institutions, roles and positions produced over time, transforming the economy and polity and in turn, getting transformed in significant ways. In this study, we use public space in its narrower sense, though any discussion of public space is intrinsically linked to the larger concept of the public sphere. Therefore, for instance, when in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries Mary Wollostonecraft, John Stuart Mill and Harriet Taylor Mill wrote advocating the entry of women into the public sphere as rational beings or in the 1960s, Betty Friedan encouraged women to find employment outside the private home to seek fulfilment, they were referring to an occupation of the public sphere as well as public space. On the other hand, Jurgen Habermas’s understanding of the bourgeois public sphere appears to ignore the fact that there was unequal access to public space. 2 Kroker et al, in their essay ‘Panic USA: Hypermodernism as America’s Postmodernism’ (1990) suggest that in the absence of safe places to walk in the USA, the shopping mall becomes the logical destination. They suggest that this is the safe place to exercise, especially for women. For in the mall everyone is a stranger but with an important difference: ‘Strangers in the mall are engaged in parallel play, safe in the policed crowd from victim city … The owners of the mall like it of course, but only up to a certain point … they have a definite image they want to portray—up-scale—so they have security guards to move people around and out’ (450). 3 Post-modern theorists of space suggest that social structure and space are not mutually exclusive concepts and neither are they related to each other causally. Rather, they are continuously interacting with each other in a dialectical relationship. Space thus, is in a constant state of becoming, in a radical departure from earlier ideas of a static, primordial entity, or one which passively reflected social structures. For French Marxist thinker Henri Lefebvre, ‘Space is not a thing but rather a set of relations between things.’ In his book, The Production of Space written in 1974, he outlines a theory of space in which he moves away from the more geometric or architectural understanding of the term ‘space’, which referred to an empty area enclosed by a material shell, towards a vision of space as a social category and a means of production. Society here is conceptualized as being a dynamic entity and Lefebvre censures theories that ‘make society into the “object” of a systemization that must be “closed” to be complete,’ bestowing ‘a cohesiveness it utterly lacks upon a totality which is in fact decidedly open—so open, indeed, that it must rely on violence to endure’ (11). The focus has thus shifted from seeing space as a neutral setting—a background for social transformation—to understanding how socio-spatial constructs play constitutive roles in the production and reproduction of social relations. Doreen Massey (1994) argues that the identities of ‘place’ are seen as being always unfixed, contested and multiple. Places are also viewed as open and porous and not defined by placing boundaries around them. Our own conception of space was greatly influenced by the work of both Lefebvre and Massey. We understand space as a complex construction and production of an environment—both real and imagined; influenced by sociopolitical processes, cultural norms and institutional arrangements, which provoke different ways of being, belonging and inhabiting. This space simultaneously also impacts and shapes the social relations that contributed to its creation. The term, ‘space’ is used not as a given but as a something which is produced and constructed through the multi-layered contexts of perception, imagination, political economy, cultural norms, structures, institutional arrangements and the everyday actions of each one of us. For a discussion on the multiple concepts and constructions of space, see among others, de Certeau (1984), Lefebvre (1991), McDowell (1999), Sennett (1994) and Soja (1989). 4 See, for instance, Grosz (1995), Massey (1994), Rose (1993), Spain (1992) among others. 5 However, the provision of infrastructure is not a neutral decision. Such policy decisions are made within the same patriarchal ideologies which produce gendered discrimination in the first place. 6 Under the provisions of the Indian Constitution, Article 15 allows for special provisions to be made for marginalized groups where these are not seen in violation of the principle of equality. 7 Kapur and Cossman (1996) on the subject of equality before law argue that the formal and substantive approaches have differing outcomes. In the formal approach, only those who are the same need to be treated as the same, but if the individuals or groups in question are perceived to be different, then they need not receive equal treatment. In the substantive approach, the focus is not on sameness or difference, but rather on questions of discrimination. In this approach, special provisions made for disadvantaged groups are not an exception to, but rather an integral part of the goal of equality. 8 This information is synthesized from interviews conducted with women commuters and with policemen who were posted in the ladies’ compartments of local trains. 9 For more on this argument, see Don Mitchell (2003). 10 Perceptions of ‘who’ and ‘what’ constitute public space differ greatly, but as Matt Vander Ploeg (2006) argues in his essay, when one group has a decision-making power, its ideal public space is created. He refers to Schaller and Modan’s (2005) study of how different racial/ethnic and class groups viewed their neighbourhood of Mount Pleasant in Washington DC. The Vietnamese and Latin groups viewed public space as ‘places “to hang out” and “meet friends”’ and low-income groups did not think spending money was an important part of socializing in public space (Schaller [2005]:403). Meanwhile, European-Americans associate just ‘hanging out’ in public space with suspicious behaviour and describe ‘people entering stores, buying things, having a purpose as more comforting’ (403). Thus, Schaller and Modan hardly found it surprising when the Euro-American and business-owner-dominated Neighbourhood Business Improvement District (NBID) has placed an emphasis on ‘an increased security force and more stringent loitering statutes’ in Mount Pleasant’s public spaces (403) (Schaller, Susanna, and Gabriella Modan, ‘Contesting Public Space and Citizenship: Implications for Neighbourhood Business Improvement Districts’, Journal of Planning Education and Research 24 (2005): 394–407, quoted in Ploeg [2006]). 9. Commuting 11 In 2003, a film titled Ladies Special focused on the camaraderie of women in Mumbai local trains (Ladies Special, directed by Nidhi Tuli, produced by the Public Service Broadcasting Trust, 2003). In the same year, a national television news channel aired a half-hour story on the Mumbai local trains, focusing substantially on women commuters (Mumbai Locals, in the programme 24 Hours, directed and reported by Radhika Bordia, New Delhi Television, 2003). They received a barrage of letters from women in other cities commenting on the almost idyllic situation of public transport for women in Mumbai and bemoaning the lack of such infrastructure in their own cities (Radhika Bordia, personal communication). 12 For example, writer Suketu Mehta draws a particularly evocative image of the egalitarian and cosmopolitan Mumbai local when he describes the ‘many hands stretching out to grab you on board, unfolding outward from the train like petals. As you run alongside you will be picked up, and some tiny space will be made for your feet on the edge of the open doorway’. 13 A successful example of increasing women’s access to public space through addressing their concerns about safety in public transport is the work done by METRAC (The Metropolitan Toronto Action Committee on Violence Against Women and Children), a Toronto-based community organization that works towards eliminating all forms of violence against women and children. For more, see http://www.metrac.org. 14 Two zonal railways—the Central Railway and the Western Railway— operate electric train services in Mumbai. The Western Railway operates the Western Line that runs from Churchgate to Virar. The Central Railway operates the Central (Main) Line, which runs from Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus (CST) (formerly Victoria Terminus) to Karjat and Kalyan (the Mumbai Municipal Limit ends at Mulund) and the Central (Harbour) Line which runs from CST to Panvel (the Mumbai Municipal limit ends at Mankhurd). About 181 trains are used to run 1942 services that carry about 6 million passengers every day (http://www.geocities.com/mumbairail/railway.html). One estimate suggests that these services constitute 50 per cent of all train services in the country (including long-distance trains). At the present time, the BEST management runs 337 different routes in the city. It has three routes that have ladies’ special buses (Route nos. 79, 606 and 259). A few routes ply at night but these night routes do not cover the city significantly. 15 We conducted extensive interviews with women and men bus conductors in 2004. At the time, the women conductors were operating out of the SEEPZ bus depot in Andheri (East). 16 In the local trains, some compartments are exclusively reserved for ‘ladies’ while others are ‘general’. Approximately 20 per cent of coach capacity at peak hours and about 15 per cent in non-peak hours, is reserved for women in separate bogies called ‘Ladies’ Compartments’. There are also ‘Ladies’ Special’ trains (a total of about eight on all the routes together), which are reserved entirely, or extensively for women. Until 1982, there were compartments reserved for women only during the day. After 8 p.m. at night, they became general compartments where men could enter. In 1982, women’s groups in Mumbai ran a successful sustained campaign to make these into compartments reserved for women for all twenty-four hours. There are now two first class and two second class (and some trains have three second class) ladies’ compartments. BEST buses have six seats reserved for women, two for senior citizens and two for the ‘handicapped’ on single-decker buses. On the double-decker buses, it reserves three seats each for women and handicapped persons and two seats for senior citizens. In relation to access, physically and mentally handicapped persons, senior citizens and pregnant women are permitted to board the bus from the front door, except at starting point. 17 In spite of separate compartments for women, local trains continue to be spaces fraught with some anxiety for women. There has been some debate, for example, about the grilled partition between the general and the ladies’ compartments in some trains, where there is a window opening in the grill. One can almost imagine that these partitions have their origins in the notion of men ‘keeping a benevolent paternal eye’ on women. Whether or not women want such protection is a moot point and in any case, such benevolence is not usually forthcoming. Instead, the general compartment with the partition grill is referred to as the ‘video-coach’ with a view of the women in the ladies’ compartment presumably to leer at. Further, one also finds graffiti pasted or scribbled on the inner walls of trains, on backs of bus seats, in underpasses and bridges, and toilets. Crude drawings of women’s breasts and vaginas and messages of lust and/or love addressed to women in general or specifically speaking to or of one woman in particular, constitute the large part of these. Some women find these images disturbing, some find them offensive while still others simply shrug them off as inconsequential. What they do point to, however, is the notion that the very presence of women is perceived as sexual or as sexualizing space. 18 In New Delhi’s metro rail system, inaugurated in 2002, there are some ‘women-only’ carriages, but police officers ride all the carriages, which are equipped with emergency call boxes. Women have reported feeling safe on the metro and that is partly due to the strong police presence. All passengers must pass through metal detectors, manned by several policemen, to enter the stations (AFP, 27 March 2006, http://www.sawf.org/newedit/edit03272006/index.asp). 19 Reading between their lines, we find that the reasons for this are linked to the presence of an authority—the bus conductor—who is on the bus, and in Mumbai, usually helpful. We heard many stories from women about how bus conductors would ask men to get off the bus if they harassed women. The other reason is that because the bus travels along the road—there is always a place they can get off at, in contrast to the trains where between stations there is a sense of ‘lack of place’ or a sense of empty space. 20 Hijras are a gender category in India, which includes people who do not identify as male or female. For an analysis of this community, see Gayatri Reddy, 2005 and Serena Nanda, 1990. 21 In fact, the ‘ladies’ compartments’ in local trains are marked by a graphic image of a woman, which varies from train to train. There are mainly three such images, all of which show women dressed in saris. Two out of these three images also show the women wearing a mangalsutra and a bindi— both distinct symbols of Hindu matrimony. These images do not recognize that in the last decade many working women have taken to wearing the more convenient salwar-kameez or indeed allow space for those who are non-Hindu or non-gender conforming. The abstracted image of a woman in the bus similarly suggests a middle-aged woman in a sari with her hair pulled back in a huge bun. An examination of these images suggests the ways in which women users of one form of public transport have been envisaged within the institutional structure. While there are probably no sinister motives or conspiracy theories behind these images, they are revealing of the dominant image of the ‘Indian woman’ that permeates the social subconscious. Though apparently harmless, such a mythification only serves to reproduce and perpetuate a stereotype which, by normalizing a particular kind of woman, marks all other women as others—incomplete, undesirable, and unworthy of full citizenship. Interestingly, in Haarlem, the Netherlands, and in Fuenlabrada, Spain, some of the stick figures on the traffic signals representing the person walking on the street have been given long hair and skirts, indicating that the presumed user of the street is as likely to be a woman as a man arguably enshrining women’s right to public space (http://contexts.org/socimages/2009/08/04/does-this-sign-surprise-you, accessed in August 2009). 22 http://www.mrvc.indianrail.gov.in/intr.htm, accessed in March 2007. 23 Transport and transport hubs like bus stops and railway stations also need to be designed with safety considerations in mind. A British study of gender concerns in transport found that in relation to safety, women reported a strong dislike of waiting around at bus stops, particularly in bad weather, and existing provision of shelters and seating was felt to be inadequate and badly designed. Bus stations were also criticized for being bleak, inconveniently located, lacking in facilities and for being places where women felt unsafe in the evenings (Public transport gender audit evidence base, http://www.dft.gov.uk/stellent/groups/dft_mobility/documents/page/dft_mobilit y_506790.hcsp, accessed in July 2006). 24 A report was submitted to Central Railway authorities and lighting was augmented at these stations. 25 In fact, as the split stands now, about 46 per cent commuters use the train services, with an average travelling distance of 27 kilometres, and 42 per cent use the bus services, with the average trip length being 6 kilometres. The remaining 7 per cent travel by private cars and 5 per cent by taxis and auto-rickshaws. See Balakrishnan (2006) and Date (2010). 10. Peeing 26 The inequality in access to toilets has also been illustrated in a documentary film, Q2P, directed by Paromita Vohra and produced by the Gender and Space project, PUKAR, 2006. 27 Edwards and McKie (1997) point out that research shows that women on average take twice as long as men to urinate. Research conducted in various parts of the world between 1957 and 1991 and collated by Kira (1994) record the time taken, measured in seconds, from entering to exiting a toilet. There are eight studies on men’s urination times showing averages of between 32 to 47 seconds and six studies on women showing averages of between 80 and 97 seconds. All these studies have been conducted largely in western countries with the exception of the inclusion of Japan. Such data would suggest that women need more rather than less toilets than men. As recently as December 2003, New York’s City Council introduced a legislation to double the number of public toilets for women, making it mandatory that large buildings and public spaces have a two-toone ratio of women’s to men’s toilets (A Reuters report cited in Times of India, 6 December 2003). Women take more time to urinate than men because of both biological as well as social reasons; because of the manner in which they need to pee and possible conditions such as pregnancy and menstruation, as well as because of the clothes they wear, the children that often accompany them and the bags they carry. See also Phadke (2007b). 28 Our research of illumination levels at Central Railway suburban railway stations also found that toilets were among the worst lit—the bulbs were dim and often did not work. In our interviews, few women commuters recounted using the toilets at these stations. 29 The Sulabh Shauchalaya (‘easy toilet’) sanitation movement began in the 1970s out of a concern for sanitation, ecology and scavengers. On the one hand, it aimed to make low-cost and appropriate toilets available to all urban-dwellers, especially the poor, and on the other it wished to upgrade the social status of scavengers by developing their capacity for alternate occupations. Sulabh International, as it is now known, was the first in the country to introduce the pay-per-use system by which users are charged a nominal fee for using the public toilet and the money thus collected goes towards maintenance of the facility. So successful has been Sulabh’s intervention that public toilets in Mumbai are often referred to generically as Sulabh. Women report that Sulabhs are public toilets that they don’t mind using. The Sulabh model has subsequently been replicated by other organizations. 30 The anxiety around toilets in poorer areas is also connected to inadequate water supply. Bapat and Agarwal (2003) point out that according to official data, residents of Mumbai get on an average 158 litres of water per day per person but argue that these statistics conceal the reality of acute inequality in the distribution of basic services (71). 31 It is for this reason that although the new apartment blocks constructed as part of the slum rehabilitation programme have been severely criticized for their insensitive planning, they often find favour with the residents, particularly women, because of one design feature—the attached private toilet. 32 This toilet was documented by fourth-year students of the Sir J.J. College of Architecture in 2005 as part of an elective course on Gender and Space. 33 In general, it is found that in areas of high-intensity usage and low maintenance such as railway stations and parks, the traditional Indian/Asian/squat toilet is more hygienic to use for women (since they do not need to sit in full contact with the pan), and easier to clean. Although at least some western-style WCs are required for the old and disabled, the squat WC is friendlier to a majority of women. Yet the squat toilet is a definite no-no in global Mumbai. 34 We refer here to advertising for Whisper and Kotex sanitary towels, among others. 35 Women in Mumbai have reported changing diapers in moving vehicles and on the floors of trial rooms in shops. They admit to being forced to breastfeed in musty store rooms of fancy shops, in parking lots and often, in toilets. Some have been politely but firmly told to stop breastfeeding in swanky restaurants as it was considered ‘inappropriate behaviour’. Here, one needs to qualify the fact that the issue of breastfeeding in public is nuanced by class and it is middle-class/elite women who find more censure than poor working-class women. Even spaces that are ostensibly meant for women (as consumers) are not friendly to women with children. Many malls, for instance, still lack basic facilities for breastfeeding and diaper changing; often a slab of granite placed at a low level near a mirror doubles up as a nappy-changing facility and a dressing table. One mall manager, who was retailing a Rs 4,000-worth diaper-changing table but had no such provision in his toilet, defended this in an interview by saying, ‘We don’t encourage such activities in our shop.’ In most places, there are no unisex baby-changing rooms or family toilets where both men and women can take a child to change a diaper or to urinate. But there is hope that some things are changing. Some Indian airports now have a small baby room equipped with a cot, a diaperchange table, toys and a screened-off area for breastfeeding mothers. 36 With design professionals shirking from the task of designing and building toilets, some community organizations, particularly those of the poor, have taken up the task with much seriousness and vigour. Since the 1990s, grassroots organization SPARC, in association with the National Slum Dwellers Federation (NSDF) and Mahila Milan, collectives of women slumand pavement-dwellers, has worked on designing and building community toilet blocks in several cities in India, including Mumbai and Pune. The women’s innovations to the toilet design include specially designed children’s toilets, which have smaller colourful squat plates, handles to prevent overbalancing, and smaller pit openings. Involving the community has meant a reduction in the cost of construction per toilet seat since community contractors take on the role of building and maintaining the toilets. It has also meant that local communities of the poor can use this as a tangible basis for a dialogue with national and local governments to explore the scaling up of the sanitation model. An example of this is the ‘sandaas mela’ (toilet festival) organized by the alliance, which involve the exhibition of not models but functioning public toilets designed by the users. Reflecting on these ‘sandaas melas’, anthropologist Arjun Appadurai (2002) suggests that they may well aid a transgressive politics of ‘deep democracy’. 11. Playing 37 Chowpatty is a local term used for city beaches. 38 In a number of separate exercises of imagining the city during workshops that we conducted, a majority of the participants did not even mark the sea in their mental map of the city. Ironically, half the participants said they would definitely take their visiting friends shopping to Phoenix Mills mall. 39 New York City has 6.3 acres per 1,000 residents or 25 per cent of its area as open space. According to the NGO, Action for Good Governance and Networking in India (AGNI), records in the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC)’s Development Plan Department show that the city has seen the maximum number of de-reservations of open spaces in the last five years with a total of 12,738 square metres, one-seventh the size of Oval Maidan, and essentially land meant for playgrounds and gardens, were de-reserved in that period. (Hindustan Times, 27 March 2007). 40 In the last few years, the lands of the closed and semi-functioning mills have opened up for redevelopment. In keeping with a plan suggested by a group led by architect Charles Correa, the Development Control Regulations (DCR) of 1991, governing the use of realty in Mumbai, had laid down the one-third formula. According to this, the entire mill land had to be distributed as follows: one-third of the land was to be given to the BMC for open spaces; one-third was to be given to Maharashtra Housing and Area Development Authority (MHADA) for public housing and the rest was to be used by the owner/developer for commercial development. In 2001, the Vilasrao Deshmukh–led state government, using a loophole in the Maharashtra Town and Planning Act, 1966, amended DCR 58 to DCR 58 (I), which stated: ‘Only land that is vacant on mill properties, that is, with no built-up structure, would be divided by the one-third formula.’ Several years later, the Bombay Environment and Action Group (BEAG), waking up to the implications, belatedly filed a public interest petition in the Bombay High Court challenging the amendment of DCR 58, which it said only benefited mill-owners and the builders’ lobby. The High Court struck down the sale of the five NTC (National Textile Corporation) properties and accepted the BEAG’s plea that the modified DCR 58, 2001, was arbitrary, illegal and unconstitutional. ‘By changing the definition of the open land, it deprived the city of much needed green space,’ said the court. However, subsequently, the Supreme Court not only struck down the High Court’s progressive ruling on reverting to DCR 58, 1991, but upheld the NTC’s sale. This essentially means that the mill-owners will not be required to share all their land with the BMC and the MHADA, but only the existing vacant spaces. 41 Writing about Los Angeles, Mike Davis (1990) points to the aggressive use of outdoor sprinklers in parks. He offers the example of Skid Row Park, where to ensure that the park could not be used by overnight campers or the homeless, sprinklers were programmed to come on at random times during the night. The measure was copied by stores to drive people away from the footpaths at night. Las Vegas has now adopted an ordinance making it an offence to feed ‘the indigent’. Many other cities in the USA have similar regulations limiting the distribution of charitable meals in parks. At the same time, in the last decade, the homeless population of Las Vegas has doubled. 42 For instance, one article in the Hindu said: ‘In the absence of illumination, many of the parks are taken over by criminals and anti-social elements after nightfall. Hordes of beggars, lepers, drug pushers and sex workers invade the precincts. The ornamental lamps that adorned the once verdant parks in the city have either been stolen or damaged. Burnt-out bulbs are seldom replaced and street lamps in the vicinity do not function. Saplings planted by Corporation gardeners are often stolen. Citizens complain that the parks double up as operating bases for burglars’ (Hindu, 9 September 2003). 43 In the past few years, the control of public spaces has been given a new turn by the establishment of the Advanced Locality Management (ALM) groups. Founded in 1998, ALM is a concept of citizen’s involvement with local governance. The equivalent of a neighbourhood association, the ALM is however, written into the municipal governance structure. An ALM covers a neighbourhood or street, normally about 1,000 citizens. It is registered by the local municipal Ward Office, which appoints a Nodal Officer to attend to citizen complaints. In Mumbai there are, as of today, about 658 registered ALMs in all twenty-four wards of the city (www.cleanupmumbaicity.org). Architect Neera Adarkar (2007) suggests that ALMs are a form of ‘unprecedented territorial claim made by the elite middle-class on their respective neighbourhoods.’ These groups, which have taken it upon themselves ‘to save their own neighbourhoods by cleansing and beautifying them, more often than not do not represent all the voices in the locality.’ Often these groups seek to erase the presence of hawkers or slums ‘by beautifying elements such as flower planters along the pavements and decorative fencing around playgrounds, parks and waterfronts to keep away the unwanted “others”.’ In their comparative study of ALMs and municipal ward committees, Baud and Nainan (2008) note that ALMs were basically set up in middle-class neighbourhoods of the city. Through focusing on enhanced security, infrastructure upgradation, and ‘cleansing’ of their neighbourhoods, these associations work towards ‘expanding rights to public space in their own neighbourhoods, and excluding people working in the public sector from access to such public space.’ 44 Joggers Park in Bandra (West) was one the first upmarket parks in the city. The park was opened in May 1990. This is a walking park that also has space for children to play. It is an oval park with only one entrance/exit. It has always been a paid park. 45 Segregation on the basis of class is however not just restricted to paid parks. While in paid parks this is temporal—certain times of the day/week are divided, in certain non-paid parks one observes an ongoing spatial segregation on the basis of class. For example, in Diamond Gardens in Chembur and Five Gardens, Dadar, it is noticed that the inside area of the park, particularly the children’s play area, is occupied by poorer children, especially in the afternoons—those that probably have no other access to easy entertainment. Children from middle-class families rarely, if ever, use these facilities. Middle-class adults, on the other hand, do use the park but they restrict themselves to the walking/jogging tracks that usually edge the parks. 46 This upgradation was undertaken by the Bandra West Residents’ Association and the Bandra Bandstand Residents’ Trust. 47 Any kind of ‘privatization’ of public space has implications on public usage of that space. For example, one recreation ground on Perry Cross Road in Bandra, which has been ‘adopted’ by a religious trust from the Municipal Corporation for maintenance, now has a meditation centre, four toilets, washing area and two rooms constructed on it. As a result, space for children to play has gone down drastically. The local complaint is that children are also being stopped from playing or running in the park. The comment by the representative from the trust says it better: ‘Children break benches and ruin flower beds. We just restrict football and badminton in the park.’ (‘Meditation Centre at Bandra Park irks locals’, DNA, Mumbai, 21 November 2008). 48 These conservative agendas are imprinted on the aesthetic body of the city in the shape of altered park benches, which have arm rests between single seats ostensibly to cast a literal spoke in the romantic wheel. In surveillance terms, couples in public spaces were monitored by the police in the wake of dictats imposed by Shiv Sena leader Pramod Navalkar when the Sena was in government in Maharashtra. These orders were, however, imprecisely defined, leaving decisions of what was deemed to be improper to the discretion of individual officers. For some this meant that couples could sit on Marine Drive or Bandra Bandstand for instance, facing the road but not facing the sea. For some it meant that they could not sit there at all. These attempts became in many ways something of a joke but they were all too serious. Of course, couples continue to occupy these spaces but the fact that such policing could be undertaken without overwhelming and vocal protest from civil society says something of potential for culture policing. For instance, Joggers Park has signs prohibiting romantic ‘misbehaving’— illustrated by pink lips which are crossed out. In December 2005, in Meerut (Uttar Pradesh), the police humiliated couples, including students and married couples in Gandhi Park in the city. A group of women policemen slapped couples in full view of television cameras. The crack-down called Operation Majnu, was purportedly a drive in Meerut against eve teasing in public, but in fact targeted consenting couples. Following this, the Uttar Pradesh government suspended the additional superintendent of police and the circle officer of the city and ordered a highlevel inquiry into the incidents (Press Trust of India, Meerut, 21 December 2005). 49 ‘Here, Love is a Four-letter Word’, Aneesh Phadnis, Times of India, Mumbai, 12 April 2002, http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/articleshow/6609031.cms. 50 The Advance Locality Management (ALM) group of Bandra Bandstand, an amalgam of thirty-eight housing societies, was planning to undertake the CCTV monitoring of the Bandstand seafront at a cost of Rs 4.5 lakh. The president of the ALM defended the idea of using seven cameras trained onto the promenade by saying that it was to ‘make sure that couples sit in the area decently rather than in an absurd manner that is embarrassing for other people’. (‘Bandstand under watch: residents play judge, jury’, Mumbai Mirror, Mumbai, 24 June 2010; ‘Cops switch off Bandstand ALM’s snoop cameras’, Mumbai Mirror, Mumbai, 30 June 2010). 51 Dagmar Grimm-Pretner (2004) argues that when public spaces are designed to support certain activities in exclusion of others, it is the more physically assertive and dominant groups that tend to claim them. Women in particular, he notes, then tend to stay away from such spaces. Design concepts with open, versatile spaces on the other hand, allow for multiple interpretations and thus encourage various groups to put them to differential use (Dr Dagmar Grimm-Pretner (2004), ‘Designing Public Parks and Squares in Viennese Urban Renewal Areas—Sites for Everyday Life’, in: Edinburgh College of Art: Open space—People Space, an international conference on inclusive outdoor environments, October 2004, Edinburgh, Scotland). 52 Until 1996, the Oval was under the jurisdiction of the Maharashtra state government. It was argued that as it was mainly used for cricket, local residents were detached from its maintenance. Subsequently, they petitioned the Maharashtra state government as a citizens’ group, OCRA (Oval-Cooperage Residents’ Association). When the state government did not respond, the citizens’ group took it to court. The High Court ruled in their favour, directing the government to either maintain the space or hand it over to the citizens’ group, which subsequently took over this space in 1996. 53 The Oval Maidan has a long list of rules and regulations put up in the maidan (as defined by the Sports Department – Government of Maharashtra). These include, among many others: • No commercialization through ads/posters/banners or in any other manner is permitted on the fence or inside the Maidan. • No cattle, horses, stray dogs etc. are allowed in the Maidan. • Anti-social activities are strictly prohibited. • Consuming liquor or other intoxicants is strictly prohibited. • Gates of the Maidan are closed from 10.00 p.m. to 6.00 a.m. • No hawkers and peddlers are allowed in the Maidan. • Littering, spitting and other acts of nuisance are prohibited in the Maidan. • No organized activity, show or event is permitted. • No morchas, processions or meetings are permitted. • In general, except cricket no other organized activity is permitted. • Users of Maidan do so at their own risk. 54 Like the Oval, the Horniman Circle Garden has also been ‘beautified’ as part of the conservation movement in Mumbai. Similarly fenced and gated, the garden is further densely planted with multiple kinds of shrubs and climbing creepers along with some fine old trees. While it is an excellent example of landscaping, it cuts complete visibility from the streets outside. Even within the garden, plants create visual partitions between spaces. Such a design encourages a more languorous use rather than active sports of any kind. As such, women—whom our research has demonstrated cannot hang-out in public space without purpose—are fundamentally discouraged from using it. Men, on the other hand, are found making the most of what the gardens have to offer—having lunches, chatting, playing cards and even having their afternoon siestas. Even if women were to overcome social stigma and access the gardens to hang out alone, the visual disconnection of the inside with the outside and the multitude of men there makes it difficult for them to do so. 55 Urban designer William H. Whyte notes that, ‘So-called “undesirables” are not the problem. It is the measures taken to combat them that is the problem. The best way to handle the problem of undesirables is to make the place attractive to everyone else’ (quoted in the Project for Public Spaces, http://www.pps.org/info/placemakingtools/placemakers/wwhyte, accessed in December 2008). An example of this in action is the Dufferin Grove Park in Toronto. Imagine this—you step out of your door, walk to your local park, knead some fresh dough, pop it in the communal oven, and within minutes you have freshly baked bread or pizza ready. By installing a wood-fired community oven, this Canadian park encouraged all kinds of people, including lower-class families with children, to use it. By making the park a space populated by all kinds of people, they effectively decreased the possibility of unwanted activities such as drug use in the park (http://www.pps.org/topics/affiliated/a_woodfired_communal). This is just one example of how a park was creatively made more inclusive and welcoming to the community that lives around it. 12. Designed City 56 Such a passive view of the material environment has not been consistent through history. Historically, an articulation of the transformative potential of material culture in general and material space in particular, began in the late nineteenth century with the Arts and Crafts movement in reaction to the perceived decrepitude of industrial society. In the early twentieth century, the design of the built environment was attributed with the ability to almost single-handedly change society. Architectural modernism in particular was fuelled by a belief in such an achievable utopian social ideal which a socially engaged architecture would bring about. In the 1960s, this Modernist utopianism (best known through the work of Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius and Mies van der Rohe) along with its companion ideals of humanism and universal idealism were critiqued severely by emerging paradigms of thought, for being univalent and insentient to the complexities and contradictions of lived experience. Architecture since the Modernists has been diffident about its larger social relevance. However, it is important to understand that critiquing the megalomaniacal belief in the omnipotence of the material environment does not mean that it has no power or ability beyond reflecting/following the evolution of the social structure. 57 The elective course ‘Interrogating the City: Gender, Space and Power’ was conducted for fourth-year students at the Sir J.J. College of Architecture, Mumbai, from December 2004 to April 2005. 58 There exist successful examples of change brought about where cities have taken designing for safety seriously. One such example is that of the Metro Action Committee on Public Violence against Women (METRAC), founded in 1984, by the council of metropolitan Toronto. Consisting of eighty allwomen members from across disciplines, METRAC has developed a comprehensive and multi-disciplinary approach to women’s safety which has more importantly shifted the locus of knowledge from technical specialists to the users themselves. For example, in a study of High Park—the city’s largest park—METRAC prepared an extensive report based on an active engagement with women park users. Amongst the factors they considered were lighting, sight/visibility, entrapment possibilities, ear and eye distance, movement predictors (such as pathways and tunnels), signage information, visibility of park staff/police, public telephones, assailants’ escape routes, maintenance levels, parks programming officials and isolation, the most critical single factor. See http://www.metrac.org. 59 Daily News and Analysis, 31 May 2006 and June 2006 60 Exercise designed by Shilpa Ranade. See also Ranade (2007) and Phadke, Khan and Ranade (2005). 61 In our ethnographic studies of coffee shops, we found that women on their own chose to sit in very specific places: usually at the edges of the shop facing the street with their back to the wall. Women often instinctively protect their backs and locate themselves where they can see people approaching them. This is interesting given that all women interviewed unanimously said that they do not feel the threat of harassment inside coffee shops though of course ‘sometimes people stare inside as well’. 62 One of the reasons that much of our public infrastructure is designed taking men as the universal/neutral ideal is that there are not enough women in decision-making bodies at various levels of design, be it governmental bodies that make city-level design decisions, architectural firms in private practice or product designers who design street furniture/graphics. Even women who belong to these professions often feel the pressure to underplay their identities as women while projecting a ‘neutral’ professional front which more often than not mirrors and reinforces the male-centric work ethic and perspective on design. This absence and reluctance on the part of women translates into their special needs being grossly overlooked. Architect and teacher Neera Adarkar recounts ironically the horror her students display at being asked to design a ladies’ compartment in a local train. As a result, of such sentiments on the part of not just students but urban planners and designers as well, the design of various infrastructural facilities that do exist, fail to provide for the specific needs of women. 63 Srivastava et al (2004) contend that defining urbanity in only one form—as multi-storeyed apartment blocks—is an impractical and unidimensional way of understanding the city. It is rooted in the conceptual inability of planners to accept diverse ways of being urban. They suggest that slums generate a diversity of built form and they deserve special attention by urban planners who should look at them more in terms of being ‘housing solutions’ rather than just problems. 64 Examples of this are the Supreme Court judgements related to the redevelopment of mill lands and recent amendments to Development Control rules 33(7) and 33(9). In 2006, the Supreme Court overturned an earlier ruling by the Bombay High Court that determined the share of the mill lands between private and public interests. Consequently, instead of having to share a portion of their entire parcel of land with government bodies—with possibilities for creating open public places—the mill-owners were allowed to retain all the built-up areas for sale, and share only the remaining open spaces, thus drastically reducing the land available for the public. In late 2008, the Supreme Court once again overruled the Bombay High Court and upheld amendments to the Development Control rules 33(7) and 33(9) thereby opening up the way for the redevelopment of a substantial pool of old cessed buildings. Environmental and planning activists argue that this makes a virtually unlimited Floor Space Index (FSI) available to the builders and will severely overload the existing infrastructure as well as adversely impact the quality of living in the city by depleting its already scarce open spaces. 65 The Centre for Enquiry Into Health and Allied Themes (CEHAT) (2006) study of the resettlement of a slum community in Mumbai shows that even the simple change of moving people from the horizontal structure of a slum to the vertical structure of an apartment block redefines the public–private dichotomy of space. The corridors and stairwells of these buildings are often unlit and unlike the older settlement patterns discourage social interaction and thus, reduce its sense of safety. The space beyond the building itself is similarly an anonymous no-man’s land, making it unsafe for women. The connection between the home and the outside world thus becomes fraught with anxieties and fear so that women prefer to stay indoors. The study shows that women’s access to education, work and healthcare, and their participation in public and community life is then adversely affected by the resettlement. 66 For instance, in the city state of Singapore we found precisely the clean lines and well-designed spaces of policy-maker’s dreams and while public space was relatively ‘safe’ it was also strangely sterile. As one woman we spoke to put it, ‘Public space here is completely devoid of any erotic possibilities.’ It was as if making the space clean and sanitized of dangers had also erased the pleasures and risks that people may have desired. (Research conducted during an Artist in Residency Programme under the International Symposium on Electronic Arts, at the National University of Singapore, Singapore.) 67 The emancipatory possibilities of everyday human actions to creatively reimagine social spaces, are alluded to most evocatively by de Certeau (1984). ‘The goal,’ he writes, ‘is not to make clear how the violence of order is transmuted into a disciplinary technology, but rather to bring to light the clandestine forms taken by the dispersed, tactical and makeshift creativity of groups or individuals already caught in the nets of “discipline”’. The proposition of de Certeau allows us to imagine social structures ‘from below’ so to say, opening up a critical methodology for de-materializing sociospatial structures and suggesting a subversive potential of human actions. IN SEARCH OF PLEASURE 13. Who’s Having Fun? 1 In January 2009, a Hindu right-wing group called the Sri Rama Sene barged into a pub in Mangalore and attacked the young women and men patrons on the grounds that the women were ‘violating traditional Indian values’. Subsequently, in the month of February, women wearing ‘western clothes’ were attacked and abused on the streets of Bangalore. 2 In this section we often use the older names of roads and areas which have now been changed. We use these because they continue to be used colloquially and are more easily recognizable than the new official names. 14. Can Girls Really Have Fun? 3 Bandra is also not as liberal as it is popularly perceived. ‘Good little girls’ are expected to be ‘good’ even if they can wear shorts in the suburb. Some married women, particularly those who had kept their maiden name after marriage, informed us that there were building societies in Bandra that demanded to see their marriage certificate to ensure that the couple staying on their building premises are legally married and not just ‘living together’. 4 ‘Celebrate Bandra’ is a local arts and culture festival organized by Bandraites in Bandra (West)—three such festivals have been organized in 2003, 2005 and 2007. 15. Do Muslim Girls Have Less Fun? 5 For a detailed discussion of many of the ideas in this chapter, see Khan (2007). 16. Do Rich Girls Have More Fun? 6 An example of this is Malabar Hill, an upper-class locality in South Mumbai where high-rise buildings have over the years come to be populated increasingly by business families of the Gujarati Jain and Marwari communities. The Chief Minister and Governor of Maharashtra also live in this locality, making it an area that receives more than its fair share of resources like electricity and water supply. It is also interesting to note how Malabar Hill continues to be marked as an upper-class area, although it also houses a number of chawls and slum neighbourhoods like Ramakund (near Banganga), Dhobi Ghat and Shivaji Nagar, which service the wealthy in high-rise apartments. 17. How Do Slum Girls Have Fun? 7 There are 42.6 million slum-dwellers in India—over 4 per cent of the country’s population lives in ‘dwellings unfit for human habitation’ according to the most recent census figures (Census 2001). In Greater Mumbai, more than half of the city’s 12 million population lives in informal settlements or slums on less than 16 per cent of the city’s land. Its 6.5 million slum-dwellers far outnumber those in any other city and account for 15 per cent of the entire slum population of the country. About 40 per cent of all Mumbai’s slum households have an income below the poverty line. Most slums are characterized by inadequate physical infrastructure, illegal electricity, poor water supply, open drains, and abysmal toilet facilities. In the heavy monsoon months, water flooding of houses is a common occurrence. 18. When Do Working Girls Have Fun? 8 Nariman Point is a business district in South Mumbai, built on reclaimed land. It houses several multinational corporations in high-rise buildings. There is one high-end residential building, one five-star hotel, a theatre complex and an MLA’s hostel in the area as well. The Vidhan Bhavan (the lower house of the state assembly) is also located in this area, which has high levels of security for this reason. Ballard Estate, situated in South Mumbai, was built in the early part of the twentieth century by the British. Though less known significant parts of this area, too, were reclaimed by the Bombay Port Trust between 1914 and 1918. The Bandra–Kurla Complex is a commercial zone developed by the Mumbai Metropolitan Regional Development Authority as part of a planned series of ‘growth centres’ in order to arrest further concentration of offices and commercial activities in South Mumbai. This complex has been built on marshy land on either side of Mahim Creek. The commercial development in the complex includes private and government offices (state and central), banks and wholesale establishments. 19. May Night Girls Have fun? 9 ‘No Women, No Trouble’, Mumbai Mirror, 25 March, 2008. 10 For more information, please see www.nasscom.in—under Initiatives, Women in IT, October 2007. 11 Telegraph, UK, 8 October 2006. 12 Telegraph, Kolkata, 14 May 2006. 21. Can Different Girls Think of Fun? 13 Interviews were conducted with visually, physically and audio-challenged women in Mumbai. Names have been withheld to protect identities. 14 According to two reports in Me magazine of the DNA newspaper, till the Census 2001, disabled or differently abled people were not even included in India’s census as a separate category, according to disability rights activist Anita Ghai. Disability scholar Renu Addlakha notes that people with disabilities is a very heterogeneous term—it includes a wide range from mildly visually challenged to completely blind, from hard of hearing to completely deaf, from those with orthopaedic disabilities, to those who have completely lost a limb, or are affected by polio or cerebral palsy. It includes those with cognitive disabilities, autism, dyslexia, even mental illness. Javed Abidi, chairman, National Centre for Promotion of Employment of Disabled People, quotes government figures that say that of the 70 million disabled in India, only 2 per cent are educated and a shocking one per cent are employed (‘A Long Road Ahead’, Me Magazine, DNA Publications, Mumbai, June 2008; ‘Gulf of Prejudice’, Me magazine, DNA Publications, Mumbai, April 2008). 15 The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, a landmark world treaty that India has ratified, came into force in May 2008. This treaty commits countries to acknowledge that people with disabilities experience specific kinds of discrimination that cannot be hidden under other social inequalities and puts disability rights on every country’s international agenda. 16 Section 44, in chapter 8 on Non-Discrimination in The Persons With Disabilities (Equal Opportunities, Protection of Rights and Full Participation) Act, 1995, states that the transport sector shall, within limits of their economic capacity and development for the benefits of PWDs (People With Disabilities) take special measures to adapt rail compartments, buses, vessels and aircraft to facilitate easy access, adapt toilets to allow wheelchair users to use them conveniently. They should install auditory signals at red lights on roads for the benefit or persons with a visual handicap, provide curb cuts and slopes to pavements for easy access of wheelchair users, engrave the surface of the zebra crossing and the railway platforms for persons with visual impairment, devise appropriate symbols for disability and provide warning signals at appropriate places. The Act also calls upon the government and local authorities to provide ramps, Braille symbols, and auditory signals in elevators of public buildings, hospitals, primary health centres, and other medical and rehabilitation institutions. But, tragically, over a decade later, we are no way close to a more accessible public space. 25. Can Good Girls Have Fun? 17 These are stereotypes of possible women in Chembur that point to some codes of gendered conduct, but nonetheless, are as always partial descriptions. IMAGINING UTOPIAS 26. Why Loiter? 1 See also Phadke, Ranade and Khan (2009). 2 This idea is not as far-fetched as it might first sound. There are some occasions that approximate such spaces. For instance, the mixture of crowds at a one-day cricket match or more recently, the 20/20 matches where a large number of different people come together appear to blur class and ethnic boundaries to some extent. This space is often more notional than real for the stadium might not be a very friendly space to women. Recollect, for instance, the college students who were sexually harassed in the celebration following India’s win in the 20/20 World Cup 2007 on 26 September 2007. Unfortunately, none of the girls who were molested outside Wankhede stadium registered a complaint and the police did not probe the matter any further despite media pressure. Another such space that creates a sense of connection of a notional shared space is Bollywood, particularly in the past decade as the divide between high culture and popular culture has dissolved to a great extent and Hindi films have acquired a certain kind of cultural legitimacy. Of course, at this point, one has to imagine these notional spaces being actually transformed into real public spaces where people might find the capacity to if not share connections, to share space based on a collective notion of collective rights. Loitering can thus be imagined in the mode of Foucault’s notion of a heterotopia; as a space that coexists with the space of the everyday but where the hegemonic structures of the everyday are suspended. Loitering is both a physical as well as a mental act, something that is not just executed by the body but produces and is made possible through a different kind of subjectivity. 3 ‘Gender Performativity’ is a term coined by feminist philosopher Judith Butler. Butler argues that gender is not a fixed attribute of a person, or something that is real in itself. Gender, rather, is created by the everyday repetitive performance of acts that produces the effect of a stable gendered persona. For more, see Butler (1990). 4 It is this quest for pleasure that the Consortium of Pub-going, Loose and Forward Women, a Facebook group formed in opposition to the attacks on women in a pub by the Sri Ram Sene in Mangalore, addressed in their mandate when they ‘refused’ to play the role of the ‘good women’ and claimed the right to fun for its own sake. This group at its finale numbered over 50,000 members, and built up to almost frenzied proportions with the media both in India and abroad giving them wide publicity. Not surprisingly, the Facebook group was hacked into several times. It is the same vision that propelled the irreverent campaign called the Pink Chaddi Campaign which emanated from the Consortium of Pub-going, Loose and Forward Women, which exhorted women to send the Sri Ram Sene pink chaddis (underwear) for Valentine’s Day to indicate their disdain for the brand of culture-policing they endorsed. 5 Women’s sense of frustration at having to watch themselves all the time was reflected in an online blog campaign ‘I Wish, I Want, I Believe’ (February 2007) run by the Blank Noise project, which campaigns against sexual harassment on Indian streets. One respondent wrote: ‘I wish to … just be myself … not think about who’s watching me … if I want to just sing to my heart’s content … swing about and walk the streets … laugh … express myself … without anybody misconstruing anything I do or say!!!!!’ Another fantasized: ‘I wish I could go to a tea/paan/cigarette stall at any time of day or night and not have only men flock around it and make me feel like I am intruding on their space.’ (http://blanknoiseproject.blogspot.com/2007/02/wishlist.html, accessed in August 2007). 6 When we say ‘not to be blamed for the violence’ we include those times when women were out to just have fun. When we say ‘not to be blamed’ we include not just moral judgements but also those based on rationality which say—‘but how stupid, what was she thinking of going out so late,’ or variations on that theme. In the recent case of the sexual assault of a young international student in Mumbai by six men (2009), the question was often raised in conversation of the young woman’s ‘stupidity’ in going to an empty flat with six men. Here it is important to point out that many other women (and men) have done similar things without adverse outcomes. The problem must be located not in the woman’s desire to have fun, but in the men’s plan to commit a crime. 7 Given recent fears of terrorism and increased concerns relating to security in public places (which terrorists usually target in order to create widespread panic and to draw immediate attention to their cause), our vision to make loitering more acceptable may seem far-fetched. The immediate response to terrorist acts in public places (such as the November 2008 terrorist attacks in Mumbai, chiefly targeting hotels and restaurants) is heightened security and surveillance measures. However, it is at such times that the need to reiterate the citizenship inherent in loitering, an act of both belonging to the city and a celebration of the pleasures afforded by the city, is the most important. If we choose surveillance and restrictions over access, then we allow the forces of terror to succeed in building a city of fear. 8 The contemporary women’s movement (post-1970s) successfully focused on issues of violence against women bringing about changes in the law. It succeeded in bringing to the foreground issues of rape, dowry deaths, female foeticide, among others. The anxiety with regard to pleasure is then often related to the fear that if pleasure gets on the agenda, it might derail the struggles and undermine the righteous and moral grounds on which the women’s movement has fought for women’s rights. As a result, even within the women’s movement, women do not place themselves or their desires centre-stage because this might be tagged as selfish, self-serving and divisive. 9 We are aware of the limitations of using the discourse of rights in this argument given the feminist critique of rights as being individualistic, reifying liberalism and often reflecting existing hierarchies of all kinds and thus limiting the terms of the debate. This critique is both valid and very valuable. At the same time, the language of rights is also a powerful tool to promote greater inclusion and participation in quest of a more egalitarian citizenship, not the least because it has a wide acceptability and for now is perhaps the best way to articulate both the entitlement to be free of violence and the claim to pleasure. 10 Sakhawat Hossain (1905) paints a world, ‘Ladyland’ where women rule in ecologically friendly cities and men are cloistered in mardanas. 11 The only exception to this was a workshop we conducted for Muslim women in May 2009 at a women’s library in Mumbra in Thane district, just outside Mumbai city limits. Here the young women, many of whom wore full burkhas were full of ideas of their utopias. One of them wanted to walk out on the streets at 1 a.m. Another wanted to use a local park which from her description was well designed (being open on all four sides) but was always peopled by men and boys while her friend wanted an open sports field where women could learn all sorts of games. One girl said she’d like to spend time in the local market without having to run home in a hurry. And another one emphatically declared, ‘We want to occupy as much space in public as men do.’ These were young women between the ages of sixteen and twenty-five who negotiate hard with their families for every extra bit of space that they are allowed to access. 12 In City of Quartz (1990), Mike Davis paints a dystopic vision of a deeply segregated Los Angeles, where attempts to cleanse the city of its undesirable elements actually created insurmountable divisions between people and spaces. The city, parcelled into privatized islands of gatedspaces, has become so alienating and violent that a semblance of urban order could only be maintained by repressive policing and a further reinforcement of spatial boundaries. See also the work of Appadurai (2000), Mitchell (2003). 13 The potential in loitering might be visualized as an extension of the power of walking itself so eloquently imagined by de Certeau (1984) whose vision of walking as being simultaneously an organic act of belonging and a subversive engagement with the city informs our idea of loitering. For de Certeau, as people walk they reinscribe the city again and again, often in defiance of established patterns of urban order, each time differently making new meanings. Walking, according to him, is fundamentally an act of ‘enunciation’ through which the city—and, in effect, social order—is personalized, and in the process, altered. Besides de Certeau, ideas of the Situationist Internationale (SI) and its key figure Guy Debord continue to influence attempts to repersonalize the urban experience. Situationist philosophy is fundamentally rooted in a critique of the dehumanized capitalist city and a focus on everyday acts as key producers of urban experience. At the core of the Situationist vision of the city is the approach to urbanism as a practice rather than a discipline. Influenced deeply by this philosophy is the field of psychogeography, which combines the subjective and objective knowledge of the city. A key strategy of exploring the city for the Situationists and in psychogeography is the dérive (drift) which Debord explains as: ‘In a dérive, one or more persons during a certain period drop their usual motives for movement and action, their relations, their work and leisure activities, and let themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there …’ (Knabb, 1995) The very reality of the city then lies in its performative nature, in the random and everyday movements of people who create it in the very process of inhabiting it. References Adarkar, Neera (2007) ‘Hamara Shaher’, Communalism Combat, August– September. Agarwal, Bina (1994) A field of one’s own: Gender and land rights in South Asia, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Ainley, Rosa (1998) ‘Introduction’ in Rosa Ainley (ed.) New Frontiers of Space, Bodies and Gender, London: Routledge, pp. xiii–xvii. Anderson, Benedict (1991) Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism, London: Verso. Andrews, Caroline (2000) ‘Resisting Boundaries: using Safety Audits for Women’ in Kristine B. Miranna and Alma H. Young (eds.) Gendering the City: Women, Boundaries and Visions of Urban Life, Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield, pp. 157–168. Anjaria, Jonathan S. (2006) ‘Street Hawkers and Public Space in Mumbai’, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 41, No. 21, 2140–46. Appadurai, Arjun (2000) ‘Spectral Housing and Urban Cleansing: Notes on Millennial Mumbai’, Public Culture, Vol. 12, No. 3, pp. 627–51. Appadurai, Arjun (2002) ‘Deep Democracy: Urban Governmentality and the Horizon of Politics’, Public Culture, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 21–47. Balakrishnan, Bina (2006): ‘Urban Transportation in Mumbai’, Mumbai Reader, Mumbai: UDRI. Bapat, Meera and Indu Agarwal (2003) ‘Our needs, our priorities; women and men from the slums in Mumbai and Pune talk about their needs for water and sanitation’, Environment and Urbanization, Vol. 15 No. 2, 71–86. Bartky, Sandra (1988) ‘Foucault, Femininity and the Modernization of Patriarchal Power’ in Lee Quinby and Irene Diamond (eds.) Feminism and Foucault: Paths of Resistance. Boston: Northeastern University Press, pp. 61–86. Baud, Isa and Navtej Nainan (2008) ‘“Negotiated” Spaces for Representation in Mumbai: Ward Committees, Advanced Locality Management and the Politics of Middle-Class Activism’, Environment and Urbanization, Vol. 20, No. 2, pp. 483–99 Bayat, Asef (2007) ‘Islamism and the Politics of Fun’, Public Culture, Vol. 19, No. 3, pp. 433–59. Bhowmik, Sharit K. (2003) ‘National Policy for Street Vendors’, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 38, No. 16, pp. 1543–46. Bourdieu, Pierre (1984) (First published in 1979) Distinction: Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Bowlby, Rachael (2001) ‘Commerce and Femininity’ in Mary Evans (ed.) Feminism: Critical Concepts in Literary and Cultural Studies, London: Routledge, pp. 127–39. Burra, Sunder (2003) Changing the Rules: Guidelines for the Revision of Regulations for Urban Upgrading, Case Study India, Mumbai: SPARC, http://www.sparcindia.org/docs/CRZpaper.pdf, accessed August 2006. Butler, Judith (1990) Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, London: Routledge. Chakravarti, Uma (1998) Rewriting History: The Life and Times of Pandita Ramabai, New Delhi: Kali for Women. Chandavarkar, Rajnarayan (2004) ‘From Neighbourhood to Nation: The Rise and Fall of the Left in Bombay’s Girangaon in the Twentieth Century’, Introduction in Meena Menon and Neera Adarkar (eds.) One Hundred Years, One Hundred Voices: The Millworkers of Girangaon: An Oral History, Kolkata: Seagull Books, pp. 7–80. Chandra, Sudhir (1998) Enslaved Daughters: Colonialism, Law and Women’s Rights, New Delhi: Oxford University Press. Chatterjee, Partha (1990) ‘The Nationalist Resolution of the Women’s Question’ in Kumkum Sangari and Sudesh Vaid (eds.) Recasting Women: Essays in Indian Colonial History. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, pp. 233–53. Contractor, Qudsiya, Neha Madhiwalla and Meena Gopal (2006) Uprooted Homes, Uprooted Lives: A Study of the Impact of Involuntary Resettlement of a Slum Community in Mumbai, Mumbai: CEHAT. Date, Vidyadhar (2010) Traffic in the Era of Climate Change: Walking, Cycling, Public Transport Need Priority, Delhi: Kalpaz Publications. Davis, Mike (1992) ‘Fortress Los Angeles: The Militarisation of Urban Space’ in Michael Sorokin (ed.), Variations on a Theme Park: The New American City and the End of Public Space, New York: Hill and Wang, pp. 154–80. De Certeau, Michael (1984) The Practice of Everyday Life, Berkeley: University of California Press. Domosh, Mona and Joni Seager (2001) Putting Women in Place: Feminist Geographers make Sense of the World, New York: The Guildford Press. Donald, James (1999) Imagining the Modern City, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Dossal, Mariam (1991) Imperial Designs and Indian Realities: The Planning of Bombay City 1845–1875, New Delhi: Oxford University Press. Douglas, Mary (2002) (First published 1966) Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo, London: Routledge Classics. Dwivedi, Sharada and Mehrotra, Rahul (1995) Bombay: The Cities Within, Bombay: India Book House. Edwards, Julia and Linda McKie (1997) ‘Women’s Public Toilets: A Serious Issue for the Body Politic’, in Kathy Davis (ed.) Embodied Practices: Feminist Perspectives on the Body, London: Sage. Ehrenreich, Barbara (2006) Dancing in the Streets: A History of Collective Joy, New York: Metropolitan Books. Elizabeth Wilson (2001) The Contradictions of Culture: Cities, Culture, Women, London: Sage. Enloe, Cynthia (1990) Bananas, Beaches and Bases: Making Feminist Sense of International Politics, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. Fernandes, Leela (2000) ‘Restructuring the New Middle-class in Liberalizing India’, Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, Vol. 20, Nos. 1 and 2, pp. 88–112. Foucault, Michel (1995) (original publication 1977) Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, New York: Vintage Books. Friedberg, Anne (1993) Window Shopping: Cinema and the Postmodern, Berkeley: University of California Press. Garber, Judith A (2000) ‘Not Named or Identified: Politics and the Search for Anonymity in the City’ in Kristine B. Miranna and Alma H. Young (eds.) Gendering the City: Women, Boundaries and Visions of Urban Life. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield, pp. 19–40. Government of India (2001) Census of India, www.censusindia.net. Grosz, Elizabeth (1995) Space, Time and Perversion, New York: Routledge. Hansen, Thomas Blom (2001) Wages of Violence: Naming and Identity in Postcolonial Bombay, Princeton: Princeton University Press. JAGORI (2006) Survey on Women’s Perception of Safety in Delhi, New Delhi: Jagori. JAGORI (2007): Is This My City? Women’s Safety in Public Spaces in Delhi, New Delhi: Jagori. Kabeer, Naila (1995) Reversed Realities: Gender Hierarchies in Development Thought, London: Verso. Kandiyoti, Deniz (1991) ‘Identity and Its Discontents: Women and the Nation’, Journal of International Studies, Vol. 20, pp. 429–43. Kapur, Ratna and Brenda Cossman (1996) Subversive Sites: Feminist Engagements with Law in India, New Delhi: Sage. Khan, Sameera (2007) ‘Negotiating the Mohalla: Exclusion, Identity and Muslim Women in Mumbai’, Review of Women’s Studies, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 42 No. 17, pp. 1527–33. Knabb, Ken (ed.) (1995) Situationist International Anthology, Berkley: Bureau of Public Secrets. Kroker, Arthur, Marilouse Kroker and David Cook (1990) ‘Panic USA: Hypermodernism as America’s Postmodernism’ Social Problems, Vol. 37, No. 4, pp. 443–59. Kumar, Radha (1993) The History of Doing: An Illustrated Account of Movements for Women’s Rights and Feminism in India 1800–1990, New Delhi: Kali for Women. Lefebvre, Henri (1991) (originally published in 1974) The Production of Space, Oxford: Blackwell. Masselos, Jim (1991) ‘Appropriating Urban Space: Social Constructs of Bombay in the Times of the Raj’, South Asia, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 33–64. Masselos, Jim (1994) ‘Postmodern Bombay: Fractured Discourses’ in Sophie Watson and Kathie Gibson (eds.) Postmodern Cities and Spaces, Oxford: Basil Blackwell, pp. 199–215. Massey, Doreen (1994) Space, Place and Gender, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. McDowell, Linda (1999) Gender, Identity and Place: Understanding Feminist Geographies, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. McDowell, Linda (1999) Gender, Identity and Place: Understanding Feminist Geographies, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. McRobbie, Angela (1997) ‘Bridging the Gap: Feminism, Fashion and Consumption’, Feminist Review, No. 55, Spring, pp. 73–89. Mehta, Suketu (1997) ‘Mumbai’, Granta 57, Spring, pp. 97–126. Mehta, Suketu (2004) Maximum City: Bombay Lost and Found, New Delhi: Penguin/Viking. Mies, Maria and Vandana Shiva (1993) Ecofeminism, London: Zed Books. Mitchell, Don (1995) ‘The End of Public Space? People’s Park, Definitions of the Public, and Democracy’, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, Vol. 85, No. 1, pp. 108–33. Mitchell, Don (2000) Cultural Geography: A Critical Introduction, Oxford: Blackwell. Mitchell, Don (2003) The Right to the City: Social Justice and the Fight for Public Space, New York: Guilford. Morris, Meghan (2000) ‘Things to Do with Shopping Centres’ in Jane Rendell, Barbara Penner and Iain Borden (eds.) Gender, Space, Architecture. London: Routledge, pp. 168–81. Moser, Caroline O.N. (1993) Gender Planning and Development: Theory, Practice, and Training, London: Routledge. Nanda, Serena (1990) Neither Man nor Woman: The Hijras of India, Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing. O’Hanlon, Rosalind (1994) A Comparison Between Men and Women: Tarabai Shinde and the Critique of Gender Relations in Colonial India, New Delhi: Oxford University Press. Parsons, Deborah (2000) Streetwalking the Metropolis: Women, the City and Modernity, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Patel, Reena (2006) ‘Working the Night Shift: Gender and the Global Economy’, ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 9–27. Patel, Sujata (2003) ‘Bombay and Mumbai: Identities, Politics, and Populism’ in Sujata Patel and Jim Masselos (eds.) Bombay and Mumbai: The City in Transition. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, pp. 3–30. Patel, Vibhuti (1994) ‘Sexual Harassment by Police: Madhushree Dutta’ in Meera Kosambi (ed.) Women’s Oppression in the Public Gaze, Bombay: RCWS, pp. 107–19. Pathak, Zakia and Sunder Rajan, Rajeshwari (1992) “Shahbano” in Judith Butler and Joan W Scott (eds.) Feminists Theorize the Political. New York: Routledge, pp. 257–79. Phadke, Shilpa (2003) ‘Thirty Years On: Women’s Studies Reflects on the Women’s Movement’, Review of Women’s Studies, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 38, No. 43, pp. 4567–76. Phadke, Shilpa (2005a) ‘You Can Be Lonely in a Crowd: The Production of Safety in Mumbai’, Indian Journal of Gender Studies, Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 41– 62. Phadke, Shilpa (2005b) Middle Class Sexuality: Construction of Women’s Sexual Desire in the 1990s and Early Twenty-first Century India, Trivandrum: Achutha Menon Centre of Health Science Studies. Phadke, Shilpa (2007a) ‘Dangerous Liaisons: Women and Men; Risk and Reputation in Mumbai’, in Review of Women’s Studies, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 42, No. 17, pp. 1510–18. Phadke, Shilpa (2007b) ‘Remapping the Public: Gendered Spaces in Mumbai’ in Madhavi Desai (ed.), Gender and the Built Environment, New Delhi: Zubaan, pp. 53–73. Phadke, Shilpa (forthcoming) ‘If Women Could Risk Pleasure: Reinterpreting Violence in Public Space’ in Bishakha Datta (ed.) Nine Degrees of Justice: New perspectives on violence against women in India, New Delhi: Zubaan. Phadke, Shilpa and Sameera Khan (2006) ‘The 21st Century Politics of College Clothing (And Other Things), Agenda, Info-Change India, Issue 4, February 2006, http://infochangeindia.org/200602215620/Agenda/ClaimingSexual-Rights-In-India/The-21st-century-politics-of-college-clothing.html, accessed March 2008. Phadke, Shilpa, Sameera Khan and Shilpa Ranade (2005) ‘Teaching Gender, Framing Architecture 2’, Architecture – Time Space and People, April, pp. 22–25. Phadke, Shilpa, Sameera Khan and Shilpa Ranade (2006) Women in Public: Safety in Mumbai. Unpublished Report submitted to the Indo-Dutch Programme on Alternatives in Development (IDPAD), Mumbai: PUKAR. Phadke, Shilpa, Shilpa Ranade and Sameera Khan (2009) ‘Why Loiter? Radical Possibilities for Gendered Dissent’ in Melissa Butcher and Selvaraj Velayutham (eds.), Dissent and Cultural Resistance in Asia’s Cities, London: Routledge, pp. 185–203. Ploeg, Matt Vander (2006) ‘Rethinking Urban Public Space in the Context of Democracy and Altruism’, Urban Altruism, Calvin College, Spring www.calvin.edu/~jks4/city, accessed June 2008. Pollock, Griselda (1988) ‘Modernity and the Spaces of Femininity’ in Vision and Difference. London: Routledge, pp. 50–90. Radner, Hillary (1999) ‘Roaming the City: Proper Women in Improper Places’ in Mike Fetherstone and Scott Lash (eds.) Spaces of Culture: City Nation World. London: Sage, pp. 86–100. Ranade, Shilpa (2007) ‘The Way She Moves: Mapping the Everyday Production of Gender-Space’, Review of Women’s Studies, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 42, No. 17, pp. 1519–26. Reddy, Gayatri (2005) With Respect to Sex: Negotiating Hijra Identity in South India, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Robinson, Rowena (2005) Tremors of Violence: Muslim Survivors of Ethnic Strife in Western India, New Delhi: Sage. Rose, Gillian (1993) Feminism and Geography: The Limits of Geographical Knowledge, Cambridge: Polity Press. Rose, Gillian (1999) ‘Women and Everyday Spaces’ in Janet Price and Margrit Shildrick (eds.) Feminist Theory and the Body, New York: Routledge, pp. 359–70. Sakhawat Hossain, Rokeya (2004) (originally published in 1905) ‘Sultana’s Dream’, in Maitrayee Chaudhuri (ed.), Feminism in India, New Delhi: Women Unlimited, pp. 103–14. Sarkar, Tanika (1993) ‘The Women of the Hindutva Brigade’, Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars, Vol. 25, No. 4, pp. 16–24. Sarkar, Tanika (2001) Hindu Wife, Hindu Nation: Community, Religion and Cultural Nationalism, New Delhi: Permanent Black. Sarkar, Tanika (2005) ‘Educating the Children of Hindu Rashtra: A Note on RSS Schools’ in Christophe Jaffrelot, (ed.) The Sangh Parivar: A Reader, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, pp. 197–206. Sarkar, Tanika (2005) ‘The Gender Predicament of the Hindu Right’ in Christophe Jaffrelot, (ed.) The Sangh Parivar: A Reader. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, pp. 178–93. Sarkar, Tanika and Urvashi Butalia (eds) (1995) Women and the Hindu Right, New Delhi: Kali for Women. Scalway, Helen (2001) ‘The Contemporary Flâneuse—Exploring Strategies for the Drifter in a Feminine Mode’, The Journal of Psychogeography and Urban Research, Vol. 1, No. 1, http://www.psychogeography.co.uk/contemporaryflaneuse.html, accessed June 2002. Sennet, Richard (1994) Flesh and Stone: The Body and the City in Western Civilization, New York, London: WW Norton & Company. Shah, Svati P. (2006) ‘Producing The Spectacle of Kamathipura: The Politics of Red Light Visibility in Mumbai’, Cultural Dynamics, Vol. 18, No. 3, pp. 269–92. Soja, Edward (1989) Postmodern Geographies: The Reassertion of Space in Critical Social Theory, London: Verso. Spain, Daphne (1992) Gendered Space, Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press. Srivastava, Rahul, Pankaj Joshi, and Vyjayanthi Rao (2004) ‘Habitat Heritage and Diversity’, unpublished report for UNESCO, Mumbai: PUKAR. Sunder Rajan, Rajeshwari (1993) ‘The Subject of Sati’ in T. Niranjana, P. Sudhir and V. Dhareshwar (eds.) Interrogating Modernity: Culture and Colonialism in India, Calcutta: Seagull, pp. 291–318. Tharu, Susie and K. Lalitha (1991) Women Writing in India, Vols. 1 and 2, New Delhi: Oxford University Press. Tharu, Susie and Tejaswini Niranjana (1999) ‘Problems in a Contemporary Theory of Gender’ in Nivedita Menon (ed.) Gender and Politics in India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, pp. 494–525. Thornham, Sue (2007) Women, Feminism and Media, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. Tindall, Gillian, (1992) City of Gold: The Biography of Bombay, New Delhi: Penguin Books. Vaid, Sudesh, and Kumkum Sangari (1996) ‘Institutions, Beliefs, Ideologies: Widow Immolation in Contemporary Rajasthan’ in Kumari Jayawardena and Malathi De Alwis (eds.) Embodied Violence: Communalising Women’s Sexuality in South Asia. London: Zed Books, pp. 267–68. Vance, Carole S. (1984) ‘Pleasure and Danger: Towards a Politics of Sexuality’ in Carole S. Vance (ed.) Pleasure and Danger: Exploring Female Sexuality, Boston: Routledge & Kegan Paul, pp. 1–28. Varma, Pavan K. (1998) The Great Indian Middle-class, New Delhi: Penguin. Varma, Rashmi (2004) ‘Provincializing the City: from Bombay to Mumbai’, Social Text, Vol. 22, No. 4, pp. 65–89. Varshney, Ashutosh (2002) Ethnic Conflict and Civic Life: Hindus and Muslims in India, New Delhi: Oxford University Press. Verdery, Katherine (1993) ‘Whither ‘Nation’ and ‘Nationalism’?’, Daedalus, Vol. 122, No. 2, pp. 37–46. Viswanath, Kalpana and Surabhi Tandon Mehrotra (2007) ‘Shall We Go Out? Women’s Safety in Public Spaces in Delhi’, Review of Women’s Studies, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 42, No. 17, pp. 1542–48. Vora, Rajendra and Suhas Palshikar (2003) ‘Politics of Locality, Community, and Marginalization’ in Sujata Patel and Jim Masselos (eds.) Bombay and Mumbai: The City in Transition, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, pp. 161–82. Walby, Sylvia (1992) ‘Woman and Nation’, International Journal of Women and Sociology, Vol. 33, No. 12, pp. 81–100. Walkowitz, Judith (1992) City of Dreadful Delight: Narratives of Sexual Danger in Late-Victorian London, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Walkowitz, Judith (1980) Prostitution and Victorian Society: Women, Class and the State, New York: Cambridge University Press. Wilson, Elizabeth (1991) The Sphinx in the City: Urban Life, the Control of Disorder and Women, Berkeley: University of California Press. Wilson, Elizabeth (2001) ‘The Invisible Flâneur’ in The Contradictions of Culture: Cities, Culture, Women. London: Sage, pp. 72–94. Wolff, Janet (1985) ‘The Invisible Flâneuse: Women and the Literature of Modernity’, Theory, Culture and Society, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 37–46. Woolf, Virginia (2001) ‘Street Haunting: A London Adventure’ in Mary Evans (ed.) Feminism: Critical Concepts in Literary and Cultural Studies. London: Routledge, pp. 17–26. Young, Iris Marion (1990) ‘Throwing like a Girl’ in Throwing like a Girl and Other Essays in Feminist Philosophy and Social Theory, Bloomington: Indiana University Press. Yuval-Davis, N. (1997) Gender and Nation, London: Sage Publications. Yuval-Davis, N. and Floya Anthias (eds.) (1989) Woman-Nation-State, London: Macmillan. Acknowledgements This book is something of a dream come true for all three of us. And as is with many realized dreams, it would not have been possible without the support, encouragement and advice of innumerable people. The Gender and Space research project which forms the basis of our book was conducted under the aegis of Partners for Urban Knowledge Action and Research (PUKAR), a research collective formed in 2001, which gave many of us an exciting space for discussion about the city and facilitated many collaborations. It is thanks in no small measure to PUKAR that the three of us met and connected. Arjun Appadurai, President of PUKAR, was a source of encouragement particularly in the writing of the project proposal. Carol Breckenridge was a great sounding board and inspired us with her immense enthusiasm for new ideas and zest for life. We would like to thank fellow-associates of PUKAR, past and present: Rahul Srivastava (who was Director of PUKAR during the first two years of our project), Shekhar Krishnan, Abhay Sardesai, Quaid Doongerwala, Pankaj Joshi, Himanshu Burte, Paromita Vohra, Nikhil Anand and Vyjayanthi Rao for discussions in the early stages of the project. Special thanks are also due to Anita Patil-Deshmukh, Director of PUKAR, and PUKAR Advisors Sheela Patel, Rama Bijapurkar and Kalpana Sharma for offering encouragement and advice at different stages of our work. At different times, Anupamaa Joshi, Bharat Gangurde, Freeda Miranda, Ishwar Solanki, and Narayan Patkar offered invaluable infrastructural and administrative support at PUKAR. The Indo-Dutch Programme for Alternatives in Development funded the Gender and Space project with an incredibly generous grant, that was equally generously administered. We would like to thank IDPAD, especially, Dr Sanchita Datta, who offered timely advice and support. A book like ours was bound to incur many intellectual debts along the way. Friends and colleagues who engaged with our ideas and collaborated on different aspects of the project for which we are grateful include: Bishakha Datta, Lakshmi Lingam, Nandita Gandhi, Nandita Shah and Shilpa Gupta. We discussed our work at various stages with many critical interlocuters: Aheli Chowdhury, Alex Mitchell, Amrita Shah, Anita Kushwaha, Anju Saigal, Anupama Rao, Ari Anand, Arvind Adarkar, Celine D’Cruz, Chayanika Shah, Dennis Ong, Devika Mahadevan, Diya Mehra, Flavia Agnes, Fleur D’Souza, Gauri Patwardhan, Geeta Seshu, George Jose, Georgina Maddox, Hasina Khan, Jasmeen Patheja, Jateen Lad, Jonathan Shapiro Anjaria, Kalpana Viswanath, Kamal Lala, Lysa John, Madhusree Datta, Maithreyi Krishnaraj, Malini Chib, Manjula Padmanabhan, Mary John, Meena Gopal, Mouleshri Vyas, Mustansir Dalvi, Nandita Godbole, Nathan Tabor, Neela Dabir, Neera Adarkar, Neera Desai, Nirupa Bangar, Nitya Raman, Noorjehan Safia Niaz, Poulomi Basu, Qudsiya Contractor, Radhika Bordia, Rukmini Barua, Sandhya Sawant, Sandhya Srinivasan, Seemanthini Dhuru, Shalini Mahajan, Sharda Ugra, Shimul Javeri, Shireen Gandhy, Smita Dalvi, Sonal Shukla, Sonya Gill, Sujata Khandekar, Surabhi Tandon Malhotra, Tarini Bedi, Tejaswini Niranjana, Ujvala Rajadhyaksha, Uma Asher and Vandana Khare. We would like to thank them for their thoughtful and reflective inputs. We had stimulating informal conversations, individually and collectively, with many others including: Aditya Pant, Ajay Noronha, Amit S. Rai, Anjali Arondekar, Anjali Monteiro, Asef Bayat, Brinda Bose, Carole S. Vance, Caroline Andrew, Caroline Osella, Champaka T.R., Chirodeep Chaudhuri, Dana Lam, Geeta Misra, Gunalan Nadarajan, Humeira Iqtidar, Irina Aristarkhova, Jackie Dugard, Janaki Abraham, Jagruti Gala, Jeroo Mulla, K.P. Jayasankar, K.V. Nagesh, Kamran Asdar Ali, Kaumudi Marathe, Lalita Fernandes, Lavanya Ramakrishnan, Linda Peake, Malavika Kasturi, Malathi de Alvis, Margaret Tan, Marina de Regt, Martina Rieker, Mary Woods, Michael Dwyer, Mukta Sharangpani, Nandita Bhavnani, Neela Saldanha, Nihal Perera, Nina Martyris, Nivedita Menon, Pramada Menon, P. Niranjana, Nishant Shah, Purnima Mookerjee, Rachel Dwyer, Radhika Chandiramani, Ramola TalwarBadam, Roopal Mehta, Reena Patel, Roxanne Varzi, Rukmani Vishwanath, Samita Sen, Sandya Hewamanne, Shaziya Khan, Shoba Ghosh, Shohini Ghosh, Sujata Patel, Sunalini Kumar, Supriya Mandrekar-Fadra, Surabhi Sharma, Svati Shah, Urmimala Sarkar, and Vinod Pavarala. Various organizations including Point of View, Aawaazi-Niswaan, the Women’s Research and Action Group (WRAG), the Association for Women’s Rights in Development (AWID) and the International Symposium on Electronic Art (ISEA) enabled us to explore our ideas through their networks. We would particularly like to thank DCOOP and the Centre for Media and Cultural Studies at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, our home bases, for providing us with resources we could draw on in moments of need. A number of people gave us an opportunity to publish our work and share it with a wider audience. We thank: Ajay Naik, Anu Kumar, the Art India team, C. Rammanohar Reddy, Dina Vakil, Geeta Seshu, Kaiwan Mehta, Leela Kasturi, Madhavi Desai, Mahesh Gavaskar, Maithreyi Krishnaraj, Melissa Butcher, Oishik Sirkar, Pankaj Joshi, Rukmini Datta, Selvaraj Velutham, Sharmila Joshi and Sujata Patel. Our pedagogic activities were critical to the development of our ideas. We would like to thank the students of the following Mumbai colleges: St. Xavier’s College, Sir J.J. College of Architecture, Sir J.J. College of Applied Art, SIES College, L.S. Raheja College of Arts, and the Habitat school at TISS. We also thank students at the Periyar College of Technology for Women at Thanjavur, the Central University of Hyderabad and the National University of Singapore for participating in workshops. We would like to particularly thank Amita Bhide, Anuja Ghosalkar, Fleur D’Souza, Jyotsna Pathare, Mustansir Dalvi, S. Mitbaukar, Sam Tareporevala, Santosh Kshirsagar, Steven Lobo, Vinay Saynekar and Vinita Bhatia. Many energetic young people worked with the Gender and Space project in various capacities. We would like to acknowledge the contributions of: Abhinandita Mathur, Anupama Jayaraman, Ateya Khorakiwala, Buvana Murali, Devika Narayan, Divya Padmanabhan, Girisha Keswani, Huma Khan, Karan Arora, Lakshmi Kutty, Mokshada Patil, Neelam Ayare, Nicola D’Souza, Nidhi Mahajan, Priyanka Shah, Rachana Agarwal, Radhika Menon, Rasika Dugal, Roseanne Lobo, Roshani Jadhav, Shriti Khandelwal, Sonal Makhija, Suresh Sawant and Uma Joshi. This is a long list but not nearly long enough. There were many other people who contributed to our research and ideas and we would like to thank all of them. Abhay Sardesai, Manesh Patel and Quaid Doongerwala have been at various times willing and not-so-willing readers of the manuscript. Their often critical comments (why did you ask if you didn’t want to know?) have honed both the book’s arguments and our ability to accept constructive criticism. If this book is our baby, then Rahul Srivastava has been its generous and brilliant midwife. He has engaged with our work, held our hands through various crises and as with the best of midwives, reminded us that we could do it. If this book is more accessible to the general reader, it is due in no small measure to the efforts of our editor Jerry Pinto for reminding us that ‘most people do not want to know that the adjective of shadow is tenebrous’. As with the best of editors he has been both friend (this writing is brilliant) and adversary (this is an ugly academic word)! We would also like to express our gratitude to Ravi Singh at Penguin India for readily agreeing to publish this book and for supporting it through the time it took us to put it together. We thank our editor at Penguin, R. Sivapriya, for gently leading us through the publication process; and Anupama Ramakrishnan and all others at Penguin for their efficient editorial support. Individually— Shilpa Phadke: I thank Shama and Suhas Phadke for nurturing my dreams and for being the kind of parents who taught me to calculate risk rather than avoid it. Shanta and Sharad Sardesai for their unstinting encouragement; Sidharth Phadke for sibling camaraderie and generosity in supplying difficult-to-find books; Gokben Yamandag and Manasi Borkar for sisterly affection and support; Malavika Kasturi for her never-say-die attitude and for sharing the holiday where the ideas of this project were born; Amit Rai for tea, sympathy and intellectual camaraderie; and Rahul Srivastava for a sustaining friendship in complicated times. Abhay Sardesai’s shared delight in the intellectual quest makes me a better scholar—thank you for the long challenging conversations, for hand-holding and most of all for knowing what this book meant and reminding me when I forgot. Aradhana, my already feisty daughter was born only months before the publication of this book. Her birth has only made this book and its vision that much more significant to me. Sameera Khan: I thank Roshnak and Irfan Khan for always being there for me and generously supporting all my initiatives big and small; Hansa and Suryakant Patel for their constant encouragement; Manesh Patel for gently cheering me on and always being ‘the wind beneath my wings’; Shahid, Ruhaina, Urmi, Vinayak and Shalaka for showing a keen interest in all I do and write; Mohini, Bharati, Fatima Bi, Madhuri, Asha, Neelam, Rehana, Mary and Taiyab for their much valued domestic and child-care help at different points of time; and finally Imaane and Atiya, my dearest daughters, who have shared most intimately my journey with the Gender and Space project and this book. They have often competed with the project and the computer for their mother’s attention but both have also made this book more personally meaningful. If my girls and their friends can enjoy more access to the city as a right, without worrying about their safety or reputation, then the ideas that have emerged from this project would truly be significant. Without the patient love and sustenance of all these people, as well as many other friends, I could never have participated in this project or book, least of all made it to the finishing line. Shilpa Ranade: I thank Ujjwala and Rajendra Ranade for being proud and encouraging parents, irrespective of what I do; Mariam and Ismail Doongerwala for their support and understanding; Rahul Ranade, the ever-concerned sibling for being the first person to take me seriously and also for his sharp editing of parts of the book; Jigna Desai, my comrade-in-arms as we grew together into a feminist consciousness; Sanjay Chikermane for his enjoyable company and discussions over the late-night drink; Ari Anand, Madhusudhan Chalasani and Tzu-I Chung for their unstinting belief in my abilities; and Quaid Doongerwala for being there, in his multiple roles as supportive colleague, intellectual sounding board and indulgent partner. I would also like to take this opportunity to recall the memory of my dear teacher Kurula Varkey, who brought home to me through example, those rare values of passion, rigour and honest-togoodness idealism. Finally, we would like to thank each other for this wonderful introduction to the intellectual and emotional pleasures of collaboration. We have learnt a great deal from each other both professionally, from our varied disciplinary perspectives and, personally from our different ways of seeing the world. We began as colleagues with a shared vision and an ability to speak to each other; we’ve ended up as friends who are going to feel quite bereft now that our impassioned and engaged meetings to think, write, talk (and eat) together are over. The Gender and Space project and this book have been a large part of our lives for more than half a decade. For many of these years, the process of research and writing consumed us. We hope we have been able to convey some of our passion with expanding women’s access to public space in the city in this book. Shilpa Phadke, Sameera Khan and Shilpa Ranade October 2010 Mumbai PENGUIN BOOKS UK | Canada | Ireland | Australia New Zealand | India | South Africa Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com. This collection published 2011 Copyright © Shilpa Phadke, Sameera Khan and Shilpa Ranade, 2011 The moral right of the author has been asserted ISBN: 978-0-143-41595-4 This digital edition published in 2012. e-ISBN: 978-8-184-75296-0 For sale in South Asia only This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.