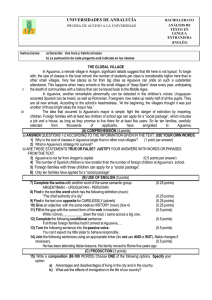

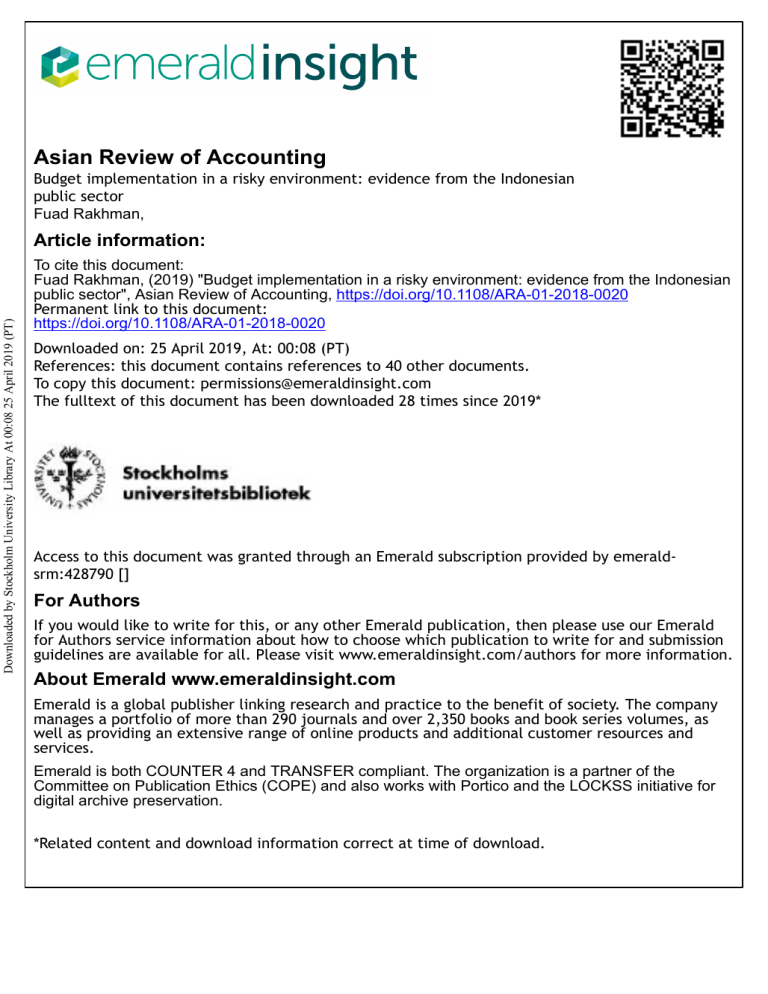

Asian Review of Accounting Budget implementation in a risky environment: evidence from the Indonesian public sector Fuad Rakhman, Downloaded by Stockholm University Library At 00:08 25 April 2019 (PT) Article information: To cite this document: Fuad Rakhman, (2019) "Budget implementation in a risky environment: evidence from the Indonesian public sector", Asian Review of Accounting, https://doi.org/10.1108/ARA-01-2018-0020 Permanent link to this document: https://doi.org/10.1108/ARA-01-2018-0020 Downloaded on: 25 April 2019, At: 00:08 (PT) References: this document contains references to 40 other documents. To copy this document: permissions@emeraldinsight.com The fulltext of this document has been downloaded 28 times since 2019* Access to this document was granted through an Emerald subscription provided by emeraldsrm:428790 [] For Authors If you would like to write for this, or any other Emerald publication, then please use our Emerald for Authors service information about how to choose which publication to write for and submission guidelines are available for all. Please visit www.emeraldinsight.com/authors for more information. About Emerald www.emeraldinsight.com Emerald is a global publisher linking research and practice to the benefit of society. The company manages a portfolio of more than 290 journals and over 2,350 books and book series volumes, as well as providing an extensive range of online products and additional customer resources and services. Emerald is both COUNTER 4 and TRANSFER compliant. The organization is a partner of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) and also works with Portico and the LOCKSS initiative for digital archive preservation. *Related content and download information correct at time of download. The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at: www.emeraldinsight.com/1321-7348.htm Budget implementation in a risky environment: evidence from the Indonesian public sector Budget implementation in a risky environment Fuad Rakhman Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia Received 24 January 2018 Revised 9 June 2018 30 December 2018 Accepted 2 March 2019 Downloaded by Stockholm University Library At 00:08 25 April 2019 (PT) Abstract Purpose – The purpose of this paper is to investigate factors affecting budget implementation among local governments in Indonesia, where rules are relatively strict and risks of facing corruption charges are high. Design/methodology/approach – This study employs regression analyses using a sample of 1,151 local government-years. Findings – This study finds that the level of budget implementation is affected by the leadership factors (i.e. mayors’ term, tenure and age) and the proportion of capital expenditures. The level of budget implementation is relatively lower when the mayor is in the second term, is in the early years of the five-year tenure and is over 60 years old. Higher proportion of capital expenditures also reduces the level of budget implementation. Originality/value – This study contributes to the literature by presenting empirical evidence as to what factors explain the variations in the level of budget implementation among local governments especially under strict rules and a risky environment. Keywords Local government, Budget implementation Paper type Research paper 1. Introduction Budget implementation or budget execution is an important mechanism of the budgeting process (Hackbart and Ramsey, 1999). Budget implementation among governmental institutions is a major concern for central governments (Albulescu and Goyeau, 2014; Oliewo, 2015; Paliova and Lybek, 2014) as government spending usually accounts for a significant proportion of economic activities. However, most studies focus on budget preparation while not enough attention paid to budget implementation (McCaffery and Mutty, 1999). This study explores the determinants of the level of budget implementation among local governments in Indonesia, where rules on budget implementation are made very strict and risks of governmental leaders facing corruption charges are relatively high. Agency theory assumes that managers are risk and effort averse (Baiman, 1990; Jensen and Meckling, 1976). Under a strict and risky environment, risk- and effort-averse managers often opt to act cautiously in executing strategies, leading to slower budget implementation and poor strategy execution, especially when the increased risks are not associated with greater rewards as is common in governmental institutions. Evidence suggests that managers who take on risks without being adequately compensated for these risks will suffer poor performance (Sheehan, 2010). Poor budget implementation by mayors of local governments potentially impedes the development of the local governments in particular and has negative impacts on the economy of the country in general. Despite the critical impacts of budget implementation on national economies, studies investigating the factors affecting budget implementation among governmental institutions The author would like to thank two anonymous reviewers and the editor, the participants of the 2016 European Accounting Association annual meeting in Maastricht, the Netherland and of the research workshop at the Department of Accounting, UGM for comments. The author thanks the Faculty of Economics and Business, UGM for the research grant. Asian Review of Accounting © Emerald Publishing Limited 1321-7348 DOI 10.1108/ARA-01-2018-0020 Downloaded by Stockholm University Library At 00:08 25 April 2019 (PT) ARA remain scarce. An examination of budget implementation in the context of Indonesian local governments is important for the following reasons. First, Indonesia provides a unique setting where rules on budget implementation by local governments are arranged in a relatively strict manner to minimize the possibility of corruption. For example, existing rules require that any governmental project or procurement involving funds of at least 200m rupiahs (around $15,385, with $1 ¼ Rp13,000) be completed through bidding instead of a direct appointment. If the project fails to attract more than one bidder, the bidding process has to be restarted over again. Many believe that such rules have become a source of slow and frustrating budget implementation among governmental institutions[1]. Second, with the strong efforts by the Corruption Eradication Commission in Indonesia to track down corruption among governmental officials, implementing budgets through program executions becomes riskier for governmental executives. As of early 2014, in the course of the 10 years since the era of the direct election of governmental leaders (presidents, governors and mayors) began, 318 governmental leaders (including governors and mayors) had been charged with being suspects of corruption ( Jawa Pos, 2014). Interestingly, some of them were charged merely because they did not follow the correct procedures instead of the intention to steal public money. This statistic creates concerns and leads to overly cautious behavior on the part of mayors to minimize the possibility of facing corruption charges, resulting in slow and weak budget implementation[2]. In 2015, for example, by the end of June, the budget realization among provincial and local governments only reached 25.9 and 24.6 percent, respectively (Republika, 2015), indicating slow program implementation at the national level[3]. Even though each local government is required to prepare a balanced budget, this study shows that on average local governments only spent 90 percent of the overall budget (and only 83 percent of the capital budget), leaving a large chunk of the remaining funds unused by the end of year. In light of the relatively strict environment and under a higher risk associated with implementing budgets, it is interesting to explore what factors would affect the extent of budget implementation among local governments in Indonesia. This study mainly examines whether managerial factors (i.e. mayors’ ages, tenure, term and gender) affect budget implementation. This study finds that budget implementation is higher: when mayors are still reelection eligible, the closer to the election year and when mayors’ age is below 60 (i.e. a typical retirement age). This study controls for institutional factors and for the budget composition. This study further reveals that budget implementation is negatively associated with the size of the government, the status of a local government as a city (metropolitan area) and the proportion of capital expenditures out of the total budget. This study contributes to the literature by presenting empirical evidence as to what factors explain the variations in the level of budget implementation among local governments especially under strict rules and a risky environment. This study differs from other studies examining the issue of budget implementation in Indonesia at the subnational level by employing an empirical/archival approach. Some other studies have examined this issue using a descriptive (e.g. Putra et al., 2011) and a survey approach (such as Harryanto et al., 2014). This study sheds some light on the causes of low budget implementation, and some alternatives to improve the implementation of local governments’ budgets, and thus help the country maintain and support its economic growth. For example, one policy implication is that since the Indonesian central government has been very concerned about low budget implementation among local governments, more monitoring by the central government may be needed. The findings of this study suggest that monitoring should be more emphasized on mayors in the second term whose motivation is relatively low. The finding is consistent with Antia et al. (2010) stating that a shorter decision horizon is associated with greater agency costs. The research findings potentially provide constituents with the knowledge on the characteristics of governmental leaders who would better promote the development of their local government, through better program implementation. The public tendency is to reelect Downloaded by Stockholm University Library At 00:08 25 April 2019 (PT) a mayor, who performed well the first time around, to serve a second term. However, this study shows that budget implementation is usually weaker when mayors serve a second term, most probably because they are legally banned from running for a third term, and this lowers their incentive to implement programs. Further, there have been disagreements in the public discourse in Indonesia as to whether an age limit (both upper and lower) is necessary for governmental leadership positions. This study provides support for setting an upper age limit for candidates running for mayors, as the local governments whose mayors are over 60 years old tend to have relatively poor program implementation (e.g. due to higher risk aversion), as reflected by their lower budget realization. This is consistent with Roger and Suarez (1983) that risk aversion is increasing with age. 2. Institutional setting and hypotheses development The level of a budget implementation in governmental institutions is a concern for many countries. For example, budget absorption has been a big issue in many African countries (e.g. Oliewo, 2015). In the European Union, many studies have been conducted to address the absorption of the structural and cohesion funds in the EU (Albulescu and Goyeau, 2014; Paliova and Lybek, 2014). In Indonesia, slow budget implementation has been a concern since the application of the new budgeting systems where local governments cannot use funds for activities or projects other than those which were approved in the budget. 2.1 Public budgeting and budget implementation in Indonesia Indonesia currently has 34 provinces (each led by a governor). Under the provinces, there are over 500 regencies (kabupaten) and cities (kota), which are led by mayors[4]. Every single local government has to go through the budgeting process annually. The process of preparing a budget for the next fiscal year usually starts in early June and is initiated by the executive branch, who sets general guidelines for the budget preparation. The budgeting process is relatively participative, in that the various agencies propose their budgets to be discussed and negotiated with mayors. The budget is expected to be ready, and made formal and binding, by the end of December with the approval of the local parliament. As soon as the budget becomes effective, throughout the fiscal year, the central government monitors the implementation of the budget by all governmental sectors, including local governments. Periodically, local governments submit reports on the realization of their budget to the Ministry of Finance. Since 2003, the Indonesian Government has adopted performance-based budgeting systems, which is a prominent reform around the world (Andrews, 2003, 2004). The new budgeting system is designed to improve the efficiency, effectiveness and control of public expenditures by linking the funding to the key performance indicators. One of the consequences of this adoption is that at the end of the year, unabsorbed funds cannot be used for activities or programs beyond those already outlined in the budget. Instead, the unabsorbed funds will be recognized as “excess funds” and roll over into the next fiscal period and may be used as an additional source of financing. Crain and O’Roark (2004) provided evidence that performance-based budgeting reduces state spending per capita by at least 2 percent. Previously, the government implemented a “use it or lose it” policy. Under this policy, there were huge incentives to spend funds especially near the fiscal year’s end to avoid fund expirations and to reduce the probability of the central government cutting their budget in the following fiscal year (Fichtner and Michel, 2016). On the one hand, the “use it or lose it” policy improves budget realization. On the other hand, however, it potentially creates irresponsible behavior by the local governments and agencies near the end of the fiscal year, as they would spend any remaining funds on items or projects that would benefit neither the institutions nor the people. Thus, local governments spend a huge amount of money just for the sake of avoiding fund expiration and face zero opportunity costs, hurting the local Budget implementation in a risky environment Downloaded by Stockholm University Library At 00:08 25 April 2019 (PT) ARA governments’ budget efficiency. Liebman and Mahoney (2017) documented evidence that year-end spending sprees among US governmental agencies (where the “use it or lose it” policy applied) is associated with lower quality projects. The central government has an interest in making sure that the limited resources appropriated in the budgets are utilized in the most effective and efficient way. With the approval of the parliament, the central government abolished the “use it or lose it” policy in 2003 and let unabsorbed funds to roll over into the next period. However, a persistent problem in the budget realization is that local governments are usually slow in implementing their programs in the first semester of the fiscal year. The central government has observed that most of the time, large proportions of the available funds are spent near the end of the fiscal year. Unfortunately, by the end of the fiscal year, under the new system, most local governments are not able to absorb the entire funds appropriated in the budget for many reasons. A report by the Indonesian National Development Planning Body identified several factors causing the slow and low implementation of governments’ budgets. One factor is related to the bureaucracy. When budget users failed to show the supporting documents for accountability purposes, the Ministry of Finance froze the budget account until they submitted all the necessary documents, which might take them some time to furnish. Another factor is related to capital expenditures, which can involve a lengthy tender process. When such projects involve building infrastructure which requires the purchase and clearance of land, the process can be slowed down due to disputes between the local government and the owners of the land (usually concerning land prices), creating unnecessary delays to the projects’ initiation and completion. Another alleged source of slow and weak budget implementation is the country’s war against corruption. Indonesia established the Corruption Eradication Commission in 2002 to minimize corruption especially in governmental institutions. The definition of corruption in Indonesia is very broad that many governmental leaders were charged with corruption even in the absence of the intention to steal public money; some of them failed to follow the proper procedures correctly, and then corruption cases were built against them when there were state losses involved. This introduces more risks associated with budget implementation among mayors of local governments, and the increased risks have been blamed for the weaker budget implementation in the country. 2.2 Hypotheses development The agency theory assumes that the interest of principals and agents are not necessarily aligned (Eisenhardt, 1989; Jensen and Meckling, 1976). The issue of conflict of interest arises from the assumption that agents are opportunistic and effort averse (Baiman, 1990). Other critical issues in the agency theory are performance measurement and incentive systems (Lambert, 2001, 2006). In light of the agency theory, if mayors perceive reelection as rewards for exerting costly efforts, it is predicted that mayors will behave differently when they are still eligible for reelection and when they are not. More specifically, when term limit binds and mayors are legally banned to run for reelection, the incentives are taken away from the equation, effectively reducing their motivation to exert efforts and to act in the best interest of the principal. In this case, agents are more likely to commit political shirking (Lott, 1990). Further, agency theory assumes that agents are risk averse ( Jensen and Meckling, 1976). In the context of Indonesian local governments where implementing budgets are associated with risks (e.g. of facing corruption charges and project failures), the effect of eliminating rewards on the level of mayors’ efforts is expected to be more profound. When agents face greater risks without being reasonably compensated, the performance would decline (Sheehan, 2010). 2.2.1 Horizon problem. Studies have found that managers nearing the end of their service (i.e. resignation or retirement) suffer from horizon problems. Managers do not have Downloaded by Stockholm University Library At 00:08 25 April 2019 (PT) strong enough incentives to invest in projects whose outcome will materialize beyond their service horizon. For example, managers with a shorter horizon tend to avoid projects with a longer payback period (Antia et al., 2010). Managers in their final year in office reduce R&D spending to maximize profits, while R&D expenditure is necessary to maintain firms’ longterm growth (Cheng, 2004; Dechow and Sloan, 1991; Murphy, 1999). In the governmental setting, Alt et al. (2011) documented that US states with reelection eligible governors enjoy higher economic growth compared to those whose governors already reach the end of term limit and are legally banned from running for reelection. In their first terms, mayors have a strong desire to implement programs more extensively as they perceive that implementing programs is an “investment” that will improve their chances of getting reelected. This is because governmental leaders eligible for reelection care about reputation buildings (Besley and Case, 1995). Mayors in their second term, however, are not likely to be reelected and thus have lower incentives to implement programs in the budget. Thus, the weak budget implementation could be attributed more to a lack of incentives rather than a lack of capacity to implement programs by the leadership teams. It is expected that budget implementation is weaker when mayors are in their second term than in the first term: H1. The level of budget implementation is higher under first-term mayors than that under second-term mayors. 2.2.2 Political budget cycles. Mayors observe reelection as a reward for their performance in implementing programs. The literature on political budget cycles (Rogoff, 1990) suggests that politicians become more opportunistic as elections draw nearer and take actions that would increase their chances of getting reelected. Klein and Sakurai (2015) found that first-term mayors in Brazil reduce revenues from taxes and switch operational expenditure into capital expenditures in the last year before elections. During the five-year tenure of a mayor’s first term, it is expected that budget implementation is higher in the years nearing the election (Years 4 and 5) compared to the early years during the five-year tenure (Years 1–3): H2. The level of budget implementation is higher when closer to the election year. 2.2.3 Upper Echelon theory. The upper echelon theory (Hambrick and Mason, 1984) suggests that the strategies and outcomes of an organization reflect the characteristics and backgrounds of its top managers such as age, experience, education and socioeconomic backgrounds, and financial positions. In other words, leadership effectiveness, as reflected by organizational performance, is influenced by the characteristics of the top managers. Extant studies confirm that top managers do matter when it comes to strategy implementation and organizational performance (Chaganti and Sambharya, 1987; Díaz-Fernández et al., 2015; Norburn and Birley, 1988). The theory, for example, predicts that firms with younger managers are inclined to take risky strategies and enjoy greater growth than those with older ones. In light of this theory, in the context of local government, younger mayors are less risk averse and are more likely to implement their programs intensively and thus improve the budget realization of their local governments. It is expected that the mayors’ age is negatively associated with the level of budget implementation: H3. The level of budget implementation is negatively associated with the age of the mayor. 3. Methods 3.1 Research model This study examines the determinants of budget implementation among local governments in Indonesia. Several managerial factors that potentially affect budget implementation Budget implementation in a risky environment Downloaded by Stockholm University Library At 00:08 25 April 2019 (PT) ARA are identified. The managerial factors incorporate the characteristics and details of mayors such as their term, tenure, gender and age. The model also incorporates institutional factors such as local governments’ size, their geographic location and their status as a regency or a city (e.g. metropolitan area). Finally, the model includes the budget composition, which is measured as the proportion of capital expenditures out of the total budget. The central government commonly uses the level of budget realization as a measure of budget implementation, with the assumption that a higher budget realization indicates that more programs are being implemented. Even though budget realization reflects the amount of input (efforts) rather than output (results) of budget implementation, it is a critical indicator for the central government in Indonesia to use to evaluate the effectiveness of local governments. Accordingly, this study uses budget realization as a proxy for budget implementation. The model is presented as follows: Realizationit ¼ m0 þm1 TERM it þm2 TENRit þm3 GN DRit þm4 AGE it þm5 SI Z E it þm6 CAPEX it þm7 J AV Ai þm8 M ETROi þFixed ef f ect þe; (1) where Realizationit is the budget realization ratio as measured by the actual spending divided by the total budget of local government i at year t[5]; TERMit a dummy variable set to 1 if the mayor of a local government i in year t serves a second term, and 0 otherwise; TENRit a dummy variable set to 1 if the mayor of a local government i in year t is in the fourth or fifth year of his/her tenure, and 0 otherwise; GNDRit a dummy variable set to 1 if the mayor of a local government i in year t is a male, and 0 if a female; AGEit a dummy variable set to 1 if the age of the mayor of a local government i in year t is 60 years or older, and 0 otherwise[6]; SIZEit a natural log of the total assets of a local government i in year t; CAPEXit the capital expenditure ratio as measured by the amount of the capital expenditure budget divided by the total budget of a local government i in year t; JAVAi a dummy variable set to 1 if the local government i is situated in the islands of Java or Bali, and 0 otherwise; METROi a dummy variable set to 1 if the local government is located in a metropolitan area; Fixed effect the year fixed effect; and e the error term. I control for gender as gender affects managers’ risk preference (Khan and Vieito, 2013) and potentially affects organizational performance. The model also control for institutional factors such as the size of the institution (Aggarwal et al., 2012; McClelland et al., 2012), whether the local government is located in a metropolitan area where people are more politically active (Rosenstone and Hansen, 1993) and more involved in government’s decision making (Yang and Callahan, 2007), the proportion of its capital expenditure budget with respect to its total budget, and the geographic location whether it is situated in Java or Bali[7] as regions in these islands are known to be relatively more developed than others. Additionally, the model incorporates the year fixed effect to control for countrywide effects as the budget implementation of local governments was likely to move together across years. For example, when the economy was sluggish in a certain year, it is expected that in general the budget implementation would decline in all local governments. 3.2 Sample and data The sample of this study includes local governments from all the provinces in Indonesia[8]. This study uses financial reports released by the local governments during the periods from 2008 through 2011, during which the central government was still under the same president to control for possible variations in budget realization between presidents. The financial reports provide financial data (e.g. total budget, actual spending, total assets and capital expenditures) and institutional data (e.g. the size and location of governments, whether the local government is located in a metropolitan area). The names of mayors are mentioned on Downloaded by Stockholm University Library At 00:08 25 April 2019 (PT) the signing page of the financial reports, while the rest of mayors’ details (e.g. age, term, tenure and gender) were manually collected from various sources and websites. Local governments are required to submit financial reports on an annual basis containing a balance sheet, a budget and realization report, a cash flow statement and notes relevant to the statements. The Supreme Audit Board audits the reports and delivers an audit opinion on each individual report. The audit opinions accompanying the financial reports are diverse, ranging from unqualified to disclaimer. To increase the reliability of the financial data for this study, this study excludes observations whose financial reports received an adverse opinion or a disclaimer from the Supreme Audit Board. Thus, this study includes only those reports receiving unqualified and qualified opinions, which presumably have more reliable and accurate accounting information. The elimination of reports with an adverse or a disclaimer of opinion reduces the sample size by 496 observations. Observations with incomplete information and those with extreme and questionable values are excluded, resulting in a sample size of 1,151 local government-years. The sample selection procedure is described in Table I. Table II presents the distribution of the total budget realization and capital budget realization by year. The table shows that the capital budget realization is always lower than the total budget realization. This implies that lower budget realization is relatively more associated with the capital budget instead of the operational budget. The mean (median) capital budget realization is 82.9 percent (85 percent) during the four-year periods. The lowest capital budget realization occurred in the year 2011 with the overall average being 78.8 percent, while the highest was in 2009 with an average of 88.6 percent. The table further shows that budget realization was the lowest in 2008 where the mean (median) realization was only 89.03 percent (90 percent). In the other three years, the average budget realization was relatively similar at around 90 percent. The highest budget realization in the sample was 99 percent. Budget implementation in a risky environment 4. Results and discussions 4.1 Descriptive analysis This study uses 1,151 local government-years as the sample from the 2008 through 2011 fiscal years. Table III shows the descriptive statistics of the variables examined in this study. The average (median) budget realization during the period was 90.13 percent (91.46 percent). Initial number of observations Financial reports with an adverse opinion or disclaimer Observations with insufficient information Observations with extreme values Final sample size Year n Mean Total budget realization Min. Med. Max. 1,760 (496) (85) (28) 1,151 SD Mean Capital budget realization Min. Med. Max. Table I. Sample selection procedure SD 2008 260 0.890 0.53 0.90 0.99 0.068 0.859 0.48 0.89 0.99 0.110 2009 267 0.907 0.60 0.92 0.99 0.062 0.886 0.45 0.92 0.99 0.103 2010 298 0.903 0.68 0.91 0.99 0.052 0.795 0.44 0.81 0.98 0.112 2011 326 0.903 0.63 0.91 0.98 0.051 0.788 0.42 0.80 0.99 0.113 All 1,151 0.901 0.53 0.91 0.99 0.058 0.829 0.42 0.85 0.99 0.117 Notes: Total budget ¼ operational budget + capital budget. The total budget realization is then the weighted average realization of the operational budget and the capital budget Table II. Total budget and capital budget realization by year Downloaded by Stockholm University Library At 00:08 25 April 2019 (PT) ARA Table III. Descriptive statistics of the variables Variables n Mean Min. Q1 Med. Q3 Max. SD TREAL (%) 1,151 90.13 52.84 87.88 91.46 94.02 99.07 5.80 TERM 1,151 0.38 0 0 0 1.00 1.00 0.49 TENR (years) 1,151 2.81 1.00 2.00 3.00 4.00 5.00 1.42 AGE (years) 1,151 51.35 30.00 46.00 52.00 57.00 75.00 8.14 GNDR 1,151 0.97 0 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 0.17 CAPEX (%) 1,151 24.30 5.35 16.98 22.89 29.60 61.07 9.64 SIZE (billion rupiahs) 1,151 2,004 12 1,056 1,512 2,193 36,556 2,293 JAVA 1,151 0.35 0 0 0 1.00 1.00 0.48 CITY 1,151 0.22 0 0 0 0 1.00 0.41 Notes: TREAL ¼ the total budget realization ratio as measured by the total actual spending divided by the total budget of local government i at year t. TERM ¼ a dummy variable set to 1 if the mayor of the local government i in year t serves in the second term, and 0 otherwise. TENR ¼ a dummy variable set to 1 if the mayor of the local government i in year t is in the fourth or fifth year in his/her tenure, and 0 otherwise. GNDR ¼ a dummy variable set to 1 if the mayor of the local government i in year t is a male, and 0 if a female. AGE ¼ a dummy variable set to 1 if the age of the mayor of the local government i in year t is 60 years or older, and 0 otherwise. CAPEX ¼ the capital expenditure ratio as measured by the amount of the capital expenditure budget divided by the total budget of local government i in year t. JAVA ¼ a dummy variable set to 1 if the local government i is situated in Java or Bali, and 0 otherwise. CITY ¼ a dummy variable set to 1 if the local government is in a metropolitan area (kota), and 0 if it is a regency (kabupaten) This means that on average, every year the local governments failed to absorb nearly 10 percent of the funds in their budget. The lowest budget realization in the sample is 52.84 percent, while the largest is 99.07 percent. Around 62 percent (38 percent) of the financial reports in the sample were signed by mayors serving in their first (second) term. The average (median) age of the mayors is 51.35 years (52 years), with the youngest mayor being only 30 years old, and the oldest 75 years old. The vast majority (97 percent) of observations has a male mayor. The average (median) proportion of capital expenditures with respect to the total budget is 24.30 percent (22.89 percent), ranging from the smallest proportion of 5.35 percent to the largest proportion of 61.07 percent. The average total assets in the sample are 2 trillion rupiahs (or $148m, $1 ¼ Rp13,500), with the smallest having 12bn and the largest 36.6 trillion rupiah. Around 35 percent of the local governments in the sample are situated in Java or Bali, and 22 percent are in metropolitan areas. 4.2 Correlation analysis Table IV presents the Pearson’s correlation coefficients among variables used in this study. The coefficients in the table suggest that there is no multicollinearity issue. The strongest correlation seems to be between CAPEX and JAVA (r ¼ −0.532), indicating that the capital Variables Table IV. Correlations analysis REAL TERM TENR GNDR AGE CAPEX SIZE REAL 1 −0.046 0.033 −0.018 −0.079** −0.384** 0.022 TERM 1 −0.025 0.023 0.103** −0.058 0.090** TENR 1 0.05 0.044 0.134** 0.004 GNDR 1 0.024 0.091** −0.105** AGE 1 0.070* 0.044 CAPEX 1 −0.207** SIZE 1 JAVA CITY Notes: *,**Correlation is significant at 5 and 1 percent levels, respectively JAVA CITY 0.189** 0.088** −0.068* −0.190** 0 −0.532** 0.366** 1 −0.111** 0.054 −0.025 0.007 0.060* −0.032 0.045 0.013 1 Downloaded by Stockholm University Library At 00:08 25 April 2019 (PT) budget proportion is relatively higher in local governments outside the island of Java. This is consistent with the governmental policy created in 2008 to promote acceleration of development in less developed regions. Therefore, local governments outside the island of Java would allocate a higher percentage of funds on capital expenditures. The second largest correlation is between CAPEX and REAL (r ¼ −0.384), showing that the local governments with the higher level of capital expenditures have relatively lower program implementation. The next strongest correlation is between JAVA and SIZE, indicating that local governments situated in the island of Java tend to be larger (i.e. have more assets). Budget implementation in a risky environment 4.3 Regression results Table V presents the results of two separate regression analyses exploring the determinants of local governments’ budget implementation when the dependent variable is: the total budget implementation (TREAL) and the capital budget implementation (CREAL). The table shows that the variable TERM reduces budget implementation. This basically means that budget implementation is generally weaker when mayors are serving their second term than when serving a first term. The variable tenure (TENR) increases budget implementation, indicating that during the five-year tenure in a single term, budget implementation improves when the mayors are in their fourth and fifth years, compared to that in their first three years. Dependent variable Variables Constant TERM TENR GNDR AGE CAPEX SIZE JAVA CITY F-statistics Adjusted R2 (%) n Notes: Model: Exp. signs − + ? − − ? ? ? TREAL CREAL 1.024*** −0.050* 0.089*** 0.017 −0.055** −0.465*** −0.056** 0.021 −0.099*** 32.1 22.90 1,151 0.983*** −0.047* 0.051* 0.005 −0.060** −0.109*** −0.036 −0.107*** −0.006 18.2 14.10 1,151 Realizationit ¼ m0 þ m1 TERM it þm2 TEN Rit þ m3 GNDRit þ m4 AGE it þ m5 SI Z E it þm6 CAPEX it þ m7 J AV Ai þ m8 CI TY i þ Fixed ef f ect þ e: TREALit ¼ the budget realization ratio as measured by the actual total spending divided by the total budget of the local government i at year t. CREALit ¼ capital budget realization ratio as measured by the actual capital expenditure divided by the total capital expenditure budget of the local government i at year t. TERM ¼ a dummy variable set to 1 if the mayor of the local government i in year t serves in the second term, and 0 otherwise. TENR ¼ a dummy variable set to 1 if the mayor of the local government i in year t is in the fourth or fifth year in his/her tenure, and 0 otherwise. GNDR ¼ a dummy variable set to 1 if the mayor of the local government i in year t is a male, and 0 if a female. AGE ¼ a dummy variable set to 1 if the age of the mayor of the local government i in year t is more than 60 years old, and 0 otherwise. SIZE ¼ a natural log of the total assets of the local government i in year t. CAPEX ¼ the capital expenditure ratio as measured by the amount of the capital expenditure budget divided by the total budget of the local government i in year t. JAVA ¼ a dummy variable set to 1 if the local government i is situated in Java or Bali islands, and 0 otherwise. CITY ¼ a dummy variable set to 1 if the local government is a metropolitan area (city), and 0 if it is a regency (kabupaten). The result on the year fixed effect is not reported for brevity. *,**,***Significant at the 10, 5 and 1 percent levels, respectively Table V. Regression results Downloaded by Stockholm University Library At 00:08 25 April 2019 (PT) ARA This might be interpreted as the mayors speeding up their program implementation as elections draw nearer to increase the chances of them getting reelected. The results further show that the mayors’ age (AGE) negatively affects budget implementation. More specifically, this study finds that budget implementation is significantly weaker when a mayor who is older than 60 years controls the local government[9]. Research suggests that young managers are more willing to take risky strategies (Hambrick and Mason, 1984) than older managers. This finding is consistent with the view that older managers are more risk averse and conservative. Since implementing programs especially those associated with capital expenditures in local governments are risky (e.g. risk of project failures, risk of facing corruption charges), mayors who are older than 60 are relatively more reluctant to implement planned programs, thus reducing budget realization. The results in Table V further suggest that a high proportion of capital expenditures (CAPEX) in the budget is a major source of low budget implementation. On average, a 1-percent increase in capital expenditures in the budget will reduce total budget realization (TREAL) by 0.46 percent in that year, and the result is significant at the 1 percent level. The size of the government (SIZE) is negatively associated with budget implementation. The larger the amount of total assets that a local government has, the weaker the budget implementation is. Further, budget implementation tends to be weaker among local government in metropolitan areas. Since cities (metropolitan areas) are relatively more developed, there is relatively less room for program implementation, especially those associated with infrastructure. Further, implementing programs in larger local governments is more complicated and time consuming than in smaller governments. Additionally, the results show that the capital budget implementation (CREAL) is significantly affected by the geographical location of the local governments. This study finds that when the regencies or cities are located in Java or Bali, the capital budget realization is lower. This implies that implementing programs associated with a capital budget (such as building new roads) in highly populated Java/Bali is more complex and might be constrained by the availability of land than in regencies or cities outside these two islands. 4.4 Additional analysis The results in Table V show that the mayors’ ages are a significant determinant of the local governments’ budget implementation. The results suggest that budget implementation is weaker when a mayor who is older than 60 leads a local government. As an additional analysis, Table VI presents the budget implementation by the mayors’ age groups. The table shows that total budget realization is consistently above 90 percent for age groups I through III where the mayors’ ages are 60 years or below. However, for age group IV (61–65 years), the average budget realization significantly declines to 86.5 percent. Further, for the mayors in age group V (above 65 years old), the budget realization gets even worse, down to an average of 85.3 percent. A similar pattern is observed for the capital budget realization where age 60 seems to be the critical turning point for the realization level. Age group Mayors’ age (years) Table VI. Average budget realization by mayors’ age Total Number of observations 1,151 Total budget realization 0.901 Capital budget realization 0.829 Note: ***Significant at 1 percent level I o41 II 41–50 III 51–60 IV 61–65 V W65 χ2 value 113 0.901 0.816 386 0.907 0.832 502 0.901 0.836 125 0.865 0.812 25 0.853 0.766 299.3*** 331.5*** Downloaded by Stockholm University Library At 00:08 25 April 2019 (PT) 5. Conclusions and limitations 5.1 Conclusions This study explores the determinants of budget implementation among local governments in Indonesia. This study investigates if managerial factors affect the level of local governments’ budget implementation by controlling for institutional factors and the budget composition. With respect to managerial factors, this study finds that budget implementation is weaker when mayors serve the second term, increasing the agency costs (Antia et al., 2010). Due to the election laws on governmental leaderships, mayors serving their second term are not eligible for reelection ( for a third term) regardless of their performance. This apparently reduces the incentives for a mayor to implement programs when the mayor is serving his/her second term, which apparently hurt the budget implementation. Further, during mayors’ five-year tenure, the budget implementation tends to be weaker in the first three years than in the last two years of the term of their service, consistent with the political budget cycle (Rogoff, 1990). The higher budget implementation in the fourth/fifth years could be due to the approaching reelection time. Mayors have strong incentives to implement programs in the years close to the campaign periods to boost their reputation, and thus improve their budget implementation (Shi and Svensson, 2006). This study also finds that budget implementation is affected by mayors’ age. Specifically, budget implementation is significantly weaker when a mayor over 60 years old leads the local government. This is consistent with the view that managers in or nearing their retirement age are more conservative and risk averse (Roger and Suarez, 1983), which hinder organizational long-term performance (Hambrick and Mason, 1984). This study does not find any association between the gender of the mayors and the level of budget implementation. With respect to the budget composition, this study finds that the amount of the capital expenditures as a proportion of the total budget is negatively associated with the budget implementation. The higher the proportion of capital expenditures is, the weaker the budget implementation is. Implementing programs associated with capital expenditures definitely need more efforts (e.g. through a lengthy bidding process) and is exposed to higher risks (e.g. the risk of the project’s failure, the risk of facing corruption charges) compared to implementing programs associated with routine activities using operational budgets. It is expected that budget implementation would be low when a local government allocate more resources to its capital expenditure programs. This study finds that the proportion of the capital expenditure budget is the most significant factor among all the variables in the model, which hinder the local government in achieving its maximum budget implementation. For institutional factors, this study finds that budget implementation is negatively associated with the size of the local government (proxied by its total assets). The larger the government’s size, the weaker the budget implementation. Budget implementation tends to be weaker in metropolitan areas. However, this study does not find any association between the local government’s geographic location and the budget implementation. 5.2 Limitations and further research This study uses budget realization as a proxy for budget implementation. Weaker budget implementation could be caused by two contrasting reasons: ineffective program implementation where mayors fail to implement programs or efficient program implementation where mayors use less fund to implement their programs: both will result in lower budget realization at the end of the fiscal year. This study assumes that low budget realization reflects the former, instead of the latter reason due to the fact that the central government is generally not happy with low budget realization among local governments. However, there must be to some extent some efficient local governments that Budget implementation in a risky environment Downloaded by Stockholm University Library At 00:08 25 April 2019 (PT) ARA are successful in implementing programs with less financial resources, leading to lower budget realization. Therefore, a limitation of this study is the inability to trace the origin of low realizations that leaves some funds unused. This is especially because the local governments’ current financial and performance reporting systems fail to provide information to help identify whether low budget realization is actually associated with a favorable, or an unfavorable variance. Another limitation is that this study does not incorporate factors such as government policies, economic conditions and political matters, which vary across local governments and potentially affect the budget implementation behavior. Further studies could incorporate other possible determinants of budget implementation not yet incorporated into the model. One possible determinant would be the presence of corruption charges in the years leading to the budget period. If a mayor of a local government is forced to steps down due to a corruption charge, the succeeding mayor is expected to be more conservative in implementing the government’s programs, lowering budget realization. Another determinant would be the risk preferences of the governmental leaders. A more conservative mayor is expected to be more cautious in spending the government’s funds especially those associated with capital expenditures, potentially weakening budget implementation. Notes 1. Another example of strict rules would be that in many governmental institutions, a person traveling paid for by the government has to submit ticket invoices, the boarding passes and a signature on an official travel document of the counter parties she/he visits, all to confirm that the travel actually happens and all costs are accounted for. 2. To relieve fears among governmental leaders, in early 2015, President Joko Widodo told the Attorney General to avoid criminalizing governmental leaders of corruption when the cause was administrative, rather than the intention to steal public money. 3. On August 24, 2015, President Joko Widodo gathered all the governors and mayors together to express his concerns regarding the low level of budget realization among the provincial and local governments and that it hampered the economic growth. The governors and mayors were urged to step up spending by implementing their programs using the appropriated funds in the local governments’ budgets. 4. In Indonesia, a regency is a local government area under a province and is led by a mayor, with a population ranging from tens of thousands to millions of people. A city is a local government (usually in metropolitan areas) characterized by having a higher population both in number and density, being more industrialized, and having better infrastructure compared to a regency. Since 2005, virtually all the mayors of regencies and cities have been elected directly by the people. Only mayors in the capital city areas of Jakarta are selected by the governor. 5. The calculation of budget realization follows the formula suggested by the Ministry of Finance in Rule No. 249/PMK.02/2011. 6. The age cut off in this model is set at 60 to reflect the retirement age. In Indonesia, the retirement age for governmental officers varies depending on the institution, ranging from 55 for those in military institutions to 65 in higher education institutions. 7. Java is an island in Indonesia where the capital city ( Jakarta) is located and is significantly more developed than other islands. Until recently, national development had been too focused on Java, leaving wide economic and infrastructure gaps between Java and the other islands. The island covers an area of less than seven percent of the country’s total land area, but it is occupied by more than half of the total population. This study also includes Bali in the category of relatively developed islands. 8. Due to the central government’s efforts to promote regional growth, the number of local governments kept increasing. As of mid-2015, there were 514 local governments (416 regencies (kapubaten) and 98 cities (kota)) in the 34 different provinces in Indonesia. 9. The variable AGE is significant at the 5 percent level when the partition is at 60 years old. However, the significance level improves to 1 percent when the partition is changed to 65 years old. For a further analysis, see Table VI. Downloaded by Stockholm University Library At 00:08 25 April 2019 (PT) References Aggarwal, R.K., Evans, M.E. and Nanda, D. (2012), “Nonprofit boards: size, performance and managerial incentives”, Journal of Accounting and Economics, Vol. 53 Nos 1-2, pp. 466-487, available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2011.08.001 Albulescu, C. and Goyeau, D. (2014), “EU funds absorption rate and the economic growth”, Timisoara Journal of Economics and Business, Vol. 6 No. 20, pp. 153-170. Alt, J., Bueno de Mesquita, E. and Rose, S. (2011), “Disentangling accountability and competence in elections: evidence from US term limits”, The Journal of Politics, Vol. 73 No. 1, pp. 171-186, doi: 10.1017/s0022381610000940. Andrews, M. (2003), “Performance based budgeting reforms: progress, problems and pointers”, in Shah, A. (Ed.), Handbook on Public Sector Performance Reviews, Chapter 2, Vol. 1, World Bank, Washington, DC, pp. 2.1-2.42. Andrews, M. (2004), “Authority, acceptance, ability and performance-based budgeting reforms”, International Journal of Public Sector Management, Vol. 17 No. 4, pp. 332-344. Antia, M., Pantzalis, C. and Park, J.C. (2010), “CEO decision horizon and firm performance: an empirical investigation”, Journal of Corporate Finance, Vol. 16 No. 3, pp. 288-301, available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2010.01.005 Baiman, S. (1990), “Agency research in managerial accounting: a second look”, Accounting, Organizations and Society, Vol. 15 No. 4, pp. 341-371. Besley, T. and Case, A. (1995), “Does electoral accountability affect economic policy choices? Evidence from gubernatorial term limits”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 110 No. 3, pp. 769-798, doi: 10.2307/2946699. Chaganti, R. and Sambharya, R. (1987), “Strategic orientation and characteristics of upper management”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 8 No. 4, pp. 393-401. Cheng, S. (2004), “R&D expenditures and CEO compensation”, The Accounting Review, Vol. 79 No. 2, pp. 305-328. Crain, W.M. and O’Roark, J.B. (2004), “The impact of performance-based budgeting on state fiscal performance”, Economics of Governance, Vol. 5 No. 2, pp. 167-186, doi: 10.1007/s10101-003-0062-6. Dechow, P.M. and Sloan, R.G. (1991), “Executive incentives and the horizon problem: an empirical investigation”, Journal of Accounting and Economics, Vol. 14 No. 1, pp. 51-89, available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0167-7187(91)90058-S Díaz-Fernández, M.C., González-Rodríguez, M.R. and Simonetti, B. (2015), “Top management team’s intellectual capital and firm performance”, European Management Journal, Vol. 33 No. 5, pp. 322-331. Eisenhardt, K.M. (1989), “Agency theory: an assessment and review”, The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 14 No. 1, pp. 57-74. Fichtner, J.J. and Michel, A.N. (2016), “Curbing the surge in year-end federal government spending: reforming ‘use it or lose it’ rules – 2016 update”, Mercatus Center, George Mason University, Arlington, VA, September. Hackbart, M. and Ramsey, J. (1999), “Managing public resources: budget execution”, Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, Vol. 11 No. 2, pp. 258-275. Hambrick, D.C. and Mason, P.A. (1984), “Upper echelons: the organization as a reflection of its top managers”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 9 No. 2, pp. 193-206. Budget implementation in a risky environment ARA Harryanto, H., Kartini, K. and Haliah, H. (2014), “Budget process of local government in Indonesia”, Review of Integrative Business & Economics Research, Vol. 3 No. 2, pp. 483-501. Jawa Pos (2014), “Kepala daerah terjerat korupsi”, Jawa Pos, February 15, available at: www.jpnn.com/ news/318-kepala-daerah-terjerat-korupsi (accessed November 10, 2015). Jensen, M.C. and Meckling, W.H. (1976), “Theory of the firm: managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 3 No. 4, pp. 305-360, available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X Khan, W.A. and Vieito, J.P. (2013), “CEO gender and firm performance”, Journal of Economics and Business, Vol. 67, May-June, pp. 55-66, available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconbus.2013.01.003 Downloaded by Stockholm University Library At 00:08 25 April 2019 (PT) Klein, F.A. and Sakurai, S.N. (2015), “Term limits and political budget cycles at the local level: evidence from a young democracy”, European Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 37, pp. 21-36, available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2014.10.008 Lambert, R.A. (2001), “Contracting theory and accounting”, Journal of Accounting and Economics, Vol. 32 Nos 1-3, pp. 3-87, available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0165-4101(01)00037-4 Lambert, R.A. (2006), “Agency theory and management accounting”, in Christopher, A.G.H., Chapman, S. and Michael, D.S. (Eds), Handbooks of Management Accounting Research, Vol. 1, Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 247-268. Liebman, J.B. and Mahoney, N. (2017), “Do expiring budgets lead to wasteful year-end spending? Evidence from federal procurement”, American Economic Review, Vol. 107 No. 11, pp. 3510-3549. Lott, J.R. (1990), “Attendance rates, political shirking, and the effect of post-elective office employment”, Economic Inquiry, Vol. 28 No. 1, pp. 133-150, doi: 10.1111/j.1465-7295.1990.tb00807.x. McCaffery, J. and Mutty, J.E. (1999), “The hidden process of budgeting: execution”, Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, Vol. 11 No. 2, pp. 233-257. McClelland, P.L., Barker, V.L. III and Oh, W.-Y. (2012), “CEO career horizon and tenure: future performance implications under different contingencies”, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 65 No. 9, pp. 1387-1393, available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.09.003 Murphy, K.J. (1999), “Executive compensation”, in Ashenfelter, O. and Card, D. (Eds), Handbook of Labor Economics, Vol. 3, Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 2485-2563. Norburn, D. and Birley, S. (1988), “The top management team and corporate performance”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 9 No. 3, pp. 225-237. Oliewo, M. (2015), “Low absorption of funds makes nonsense of the budget trillions”, Business Daily, June 21, available at: www.businessdailyafrica.com/analysis/nonsense-of-the-budget-trillions/ 539548-2760040-kuxeadz/index.html (accessed November 10, 2015). Paliova, I. and Lybek, M.T. (2014), Bulgaria’s EU Funds Absorption: Maximizing the Potential!, IMF Working Paper WP/14/21. Putra, A.S., Rahman, E.A. and Farhan, Y. (2011), “Sub National Budget Index: measuring the performance of 42 Indonesia local governments in budget management process”. Republika (2015), “Serapan anggaran kurang, Mendagri surati pemda”, Republika, July 7, available at: www. republika.co.id/berita/nasional/umum/15/07/07/nr2y7v-serapan- (accessed November 10, 2015). Roger, A.M. and Suarez, A.F. (1983), “Risk aversion revisited”, The Journal of Finance, Vol. 38 No. 4, pp. 1201-1216, doi: 10.2307/2328020. Rogoff, K. (1990), “Equilibrium political budget cycles”, The American Economic Review, Vol. 80 No. 1, pp. 21-36. Rosenstone, S.J. and Hansen, J.M. (1993), Mobilization, Participation, and Democracy in America, MacMillan, New York, NY. Sheehan, T.N. (2010), “A risk-based approach to strategy execution”, The Journal of Business Strategy, Vol. 31 No. 5, pp. 25-37, available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/02756661011076291 Shi, M. and Svensson, J. (2006), “Political budget cycles: do they differ across countries and why?”, Journal of Public Economics, Vol. 90 Nos 8‐9, pp. 1367-1389, available at: http://dx.doi.org /10.1016/j.jpubeco.2005.09.009 Yang, K. and Callahan, K. (2007), “Citizen involvement efforts and bureaucratic responsiveness: participatory values, stakeholder pressures, and administrative practicality”, Public Administration Review, Vol. 67 No. 2, pp. 249-264, doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2007.00711.x. Downloaded by Stockholm University Library At 00:08 25 April 2019 (PT) Corresponding author Fuad Rakhman can be contacted at: frakhman@ugm.ac.id For instructions on how to order reprints of this article, please visit our website: www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/licensing/reprints.htm Or contact us for further details: permissions@emeraldinsight.com Budget implementation in a risky environment