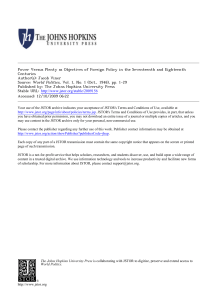

Psychological Analysis and Literary Form: A Study of the Doubles in Dostoevsky Author(s): Lawrence Kohlberg Source: Daedalus , Spring, 1963, Vol. 92, No. 2, Perspectives on the Novel (Spring, 1963), pp. 345-362 Published by: The MIT Press on behalf of American Academy of Arts & Sciences Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20026782 JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms American Academy of Arts & Sciences and The MIT Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Daedalus This content downloaded from 186.55.26.0 on Fri, 12 May 2023 00:24:45 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms LAWRENCE KOHLBERG Psychological Analysis and Literary Form: A Study of the Doubles in Dostoevsky Psychology is a knife that cuts both ways. ?The Brothers Karamazov Illness, delirium, amnesia, but why were you haunted by just those delusions and not by any others? ?Crime and Punishment To the psychologist looking at contemporary literature, there is a rather paradoxical discrepancy between the impact of psychoanaly sis upon creative and upon critical writing. While it is almost im possible to find a serious modern novel or drama which would not be profoundly different without the existence of psychoanalytic con cepts, this can hardly be said for modern literary criticism. A major factor in the impact of psychoanalytic ideas upon crea tive writing is the ability of psychoanalysis to breathe new life into old myths and literary forms. This invigorating effect springs in large part from the psychoanalytic balance of concern for inward forces and outward action, each revealing something otherwise mysterious about the person. In contrast, die introspectionism of the Jamesian psychological novel leads to an essential meaningless ness of action, while the Hemingway or "new wave" behaviorism is a complete denial of the meaning of the internal. The revivifying effect of psychoanalysis upon old literary forms is most clearly apparent in tragedy, which the Freudian world-view makes meaningful for a scientifically oriented and morally relativistic culture. Faithful to necessities apparent in its early Athenian form, 345 This content downloaded from 186.55.26.0 on Fri, 12 May 2023 00:24:45 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms LAWRENCE KOHLBERG tragedy requires a crime to be committed which is both willed and unwilled; both free and foreordained, a fated act for which the actor is yet responsible. As tragic crime is foreordained but willed, so tragic punishment is both doom and self-discovery of evil. In Athenian tragedy, the fated aspects of crime and punishment were the result of cruel but moral external forces. In the modern "psycho analytic" form of tragedy, the fated aspects of crime and punishment are the products of uncontrolled and unconscious internal forces. The crime is the fated result of immutable instinctual impulses; the inevitable doom which follows the crime is the result of unconscious and inescapable needs for punishment. Other "scientific" world views, such as the sociological determinism embodied in Dreiser's American Tragedy, provide a sense of the inevitability of crime and punishment. This inevitability, however, is the product of purely external and amoral forces, and cannot be combined with the willed self-discovery and repentance characteristic of classic tragedy. In contrast with its revolutionary impact upon creative writing, psychoanalysis seems of only minor importance to modern literary criticism. The common awareness of psychological sickness and symbol in a literary work is believed to detract, rather than add to, understanding and appreciation of the work. Critics who feel that this awareness can be used constructively, such as Burke, Guerard, Hyman, Kazin, Trilling, and Wilson use psychoanalysis primarily as myth, as one element or world-view among many which sensitize the reader of a work of art to its meaning. The construction and "proof" of a detailed psychoanalytic interpretation seems out of place in such literary criticism. Critical articles in the professional psychiatric journals present a striking contrast. In these, the literary meaning of the work of art is not considered as central to the analytic task. In contrast with the critical use of psychoanalysis as sensitizing "myth," the professional psychoanalyst attempts to use psychoanalytic theory to provide a comprehensive and true explanation of why a given writer wrote just what he did. He brings to literature the habits of the clinic which require that a decision or diagnosis be made, and the habits of a scientist which require that a hypothesis be judged, not as in spiring, but as true or false. Of all writers, none has elicited more of this case-study approach than Dostoevsky, that archetype of the psychopathological genius. Some of these studies, diagnosing Dostoevsky on the basis of bio graphical data, as if he were a case to be committed to a hospital or 346 This content downloaded from 186.55.26.0 on Fri, 12 May 2023 00:24:45 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms The Doubles in Dostoevsky a course of therapy, have come to such conclusions as, "Dostoevsky was an epileptic, schizophrene, paranoid type, complicated by hysterical overlay."1 Other studies focus upon Dostoevsky's uncon scious conflicts as projected into his novels. The classic example of this type of study is Freud's essay on Dostoevsky,2 in which he views Dostoevsky as preoccupied by parricidal impulses and resultant guilt, a conflict projected into Dmitri and Ivan Karamazov. Still other studies focus upon the analysis of a specific character in a novel as if he were a real person, coming to such conclusions as that "Raskolnikov was an autistic personality with traces of the manic depressive"3 or that "Raskolnikov's murder was a result of efforts to appease unconscious guilt due to an incestuous attachment to his sister."4 Both academic psychologist and humanist question this sort of study. In the first place, it is impossible to know whether these in terpretations are true. The characters are not real people, the bio graphical data on the author is inadequate, and a novel is not a psychological projective-test response by an author. Even if the case data were adequate, one could not achieve scientific certainty in the interpretation of a single case. Few would disagree with Kris5 that "It would seem as well demonstrated as any conclusion in the social sciences that the struggle against incestuous impulses, dependency, guilt, and aggression has remained a recurrent topic of Western literature from Sophocles to Proust." The ubiquity of certain themes in myth and hterature, though undeniable, does not, however, con tribute to certainty of interpretation of any individual case. The second reservation is an even more crucial one. What dif ference does it make to the intelligent reader's understanding of a novel to know that Dostoevsky had parricidal impulses or was an epileptic schizophrene? Even Freud seems to agree with this caveat, since he begins his essay on Dostoevsky as follows: Four facets may be distinguished in the rich personality of Dostoevsky ?the creative artist, the neurotic, the moralist and the sinner. How is one to find one's way in this bewildering complexity? The creative artist is least doubtful. The Brothers Karamazov is the most magnificent novel ever written. . . . Before the problem of the creative artist, analysis must, alas, lay down its arms. Freud would feel that his analysis of Dostoevsky helps explain the power of Dostoevsky's novel in that "It can scarcely be owing to chance that three of the masterpieces of all hterature Oedipus Rex, Hamlet, and The Brothers Karamazov should all deal with the same 347 This content downloaded from 186.55.26.0 on Fri, 12 May 2023 00:24:45 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms LAWRENCE KOHLBERG subject, parricide." In Freud's view, "parricide is the principal and primal crime of humanity as well as of the individual, and the main source of the sense of guilt"; and in some sense the power of The Brothers Karamazov hes in its confrontation of the reader with his own guilt-laden impulses in a situation in which identification with the hero is at a sufficient distance to allow "catharsis through pity and fear." Even if one granted this interpretation, it hardly explains the difference between murder in Dostoevsky and murder in Mickey Spillane. The present paper is an effort to show that psychoanalysis need not entirely "lay down its arms" before Dostoevsky, the creative artist; it will use a psychological analysis to clarify two literary prob lems important in the appreciation and understanding of Dostoev sky's novels: the first, his use of Doubles; the second, his particular and unique moral ideology. In recent years, literary critics have come to believe that an understanding of Dostoevsky's use of Doubles is the key to an under standing of the structure of his novels, a key which radically revises early critical views of Dostoevsky's novels as "badly constructed and unwieldly." An example of such a recent structural or "technique" interpretation of the Doubles is Beebe's analysis of Crime and Pun ishment: If we approach Crime and Punishment with a knowledge of Dosto evsky's character and method of writing, we are likely to be surprised at the disciplined skill the structure of the novel reveals. It meets the test of unity in action; all the parts contribute to the whole and the parts may be fully understood only when the whole is known. One of the ways in which Dostoevsky unified his novel is through his technique of "doubles." The dual nature of his heroes is, of course, a commonplace of criticism. Because his protagonists are usually split personalities, the psychological and philosophical drama in a Dostoevsky novel is expressed in terms of a conflict between opposite poles of sensibility and intelhgence, self-sacrifice and self-assertion, God-Man and Man-God, or sometimes "good" and "bad." To dramatize this conflict, Dostoevsky often gives his characters several alter-egos or doubles, each projecting one of the extremes of the split personality. Even when the hero is not present in the scene, he may represent the center of interest because the characters present, represent different facets of his personality. According to most interpretations of Crime and Punishment, the struggle within Raskolnikov becomes physical external action as he wavers between Svidrigailov, epitome of self-willed evil, and Sonia, epitome of self-sacrifice and spiritual goodness.* * J. M. Beebe, "The Three Motives of Raskolnikov," in E. Wasiolek ( edi tor), Crime and Punishment and the Critics (San Francisco: Wadeworth, 1961). This content downloaded from 186.55.26.0 on Fri, 12 May 2023 00:24:45 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms The Doubles in Dostoevsky Dostoevsky's Doubles, however, are not mere portrayals of ties between stereotyped representatives of good and evil to be found throughout good and bad fiction. They obviously contain much personal symbolic meaning and are intended to have a psychopatho logical basis. They not only express ideological values and require ments of plot but enact or express murders of kin, rapes of little girls, spider fantasies, mutilation themes, epileptic attacks, suicide, necro philia and hallucinations, and were viewed by Dostoevsky himself as forms of psychopathology. The Raw Youth says: "What then pre cisely is the 'double'? The 'double,' at any rate according to a medi cal work by an expert which I read for the purpose is nothing but the first stage in some serious mental derangement which may lead to a bad conclusion, a dualism between f eeling and willing." Not only does Dostoevsky view his Doubles as "psychopathologi cal," but his preoccupation with Doubles precedes the ideological and structural use he was to make of them in his later novels. This preoccupation on a purely psychological level is expressed in Dosto evsky's second novel, written before his Siberian exile and entided The Double, a novel which he said "contained a great deal of myself." The hero of this novel, Golyadkin, is one of Dostoevsky's typical, socially isolated petty officials desperately striving to maintain some appearance of respectability in spite of poverty, social incompetence, and deep feehngs of inferiority. He awakes in a clouded state, on the verge of a breakdown, believing that something is being got up against him by his colleagues at the office, that there is a conspiracy afloat, that his reputation has been blackened and that his enemies are trying to ruin him. After consulting his doctor he decides to attend a ball that eve ning given by his former patron ("who has been a father to him") in honor of his daughter. Golyadkin has not been invited and is under a cloud because of some unspecified recent behavior. He is refused admission by the footman, but enters the house surreptitiously and lurks in the corridor. Suddenly in contradiction to his usual self effacement, some mysterious brazen impulse "projects" him into the ballroom and leads him to insist on dancing with the daughter. He is ignominiously thrown out on the street. He then wanders about the streets and contemplates suicide by drowning. He has an uncanny feeling that there is someone near, and in terror recognizes the presence of a Double, a figure exactly hke himself, who accompanies him home. 349 This content downloaded from 186.55.26.0 on Fri, 12 May 2023 00:24:45 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms LAWRENCE KOHLBERG The next day, he finds the Double ensconced at a desk at his office, as if he had always worked there, ingratiating himself with his colleagues and superiors, and ridiculing Golyadkin. All of this Golyadkin II's misconduct is blamed on Golyadkin I, while Golyad kin II gets credit for all of Golyadkin I's efforts. Golyadkin views the Double as an indecent, shameless, malevolent toady but never theless attempts to be friendly with him and is insulted and humili ated for his pains. After agonies of humiliation, rage, fear, and suspicion, Golyadkin believes a solution awaits him. He believes he has received a note from the daughter of his patron asking him to elope with her and arranging a rendezvous. He awaits her at the appointed time in hiding outside her house, just as he had in the episode preceding the emergence of the Double. His Double trots out and hustles him into the house where a crowd is gathered, staring at him. He is suddenly surrounded by an "infinite procession of Golyadkins noisily bursting in at every door of the room." He is carried away to the lunatic asylum by his own cruel doctor while the Double hangs on to the carriage door and pokes his head in the window. In this tale, Dostoevsky's use of the Double theme of Hoffman and Gogol does not achieve any grand artistic purpose, but it does offer a compelling picture of psychopathology. Accordingly, we shall attempt to settle the purely diagnostic questions about the Double phenomena it presents before considering the literary meanings of the Double themes. The only serious treatment of The Double from a psychopatho logical view is provided in a monograph written in the early twenties by Otto Rank, Freud's "most gifted follower."6 Rank pro claims the novel to be a classic portrayal of a paranoid state. There are indeed strong resemblances between the phenomena presented in The Double and familiar psychiatric phenomena of paranoid states. Paranoid delusions or hallucinations of persecutory figures emerge from feelings of shame and pathologically low self-esteem. These delusions are presumed to be the result of the defence mechanism of "disowning projection." Shameful impulses and tend encies toward self-accusation are denied as belonging to the self and are projected upon external imagined enemies. Obviously Dostoev sky intended Golyadkin II to be a hallucination representing the assertive, shameless impulses which first "propelled" Golyadkin I into his patron's ballroom, since the novel ends with the double propelling him again into the same ballroom. Golyadkin I's sense of 350 This content downloaded from 186.55.26.0 on Fri, 12 May 2023 00:24:45 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms The Doubles in Dostoevsky low esteem, his feehng that he is being intrigued against, his life in a world in which he makes and receives veiled threats and innuen does, are indeed striking portrayals of the paranoid attitude. It also seems likely that The Double may have expressed one of Dostoevsky's states at the time of the writing of the novel, a state of feeling humiliated and "persecuted" in connection with the outbreak of previously unsuspected or unacknowledged qualities in his own personality. Just previous to writing The Double, the success of Poor Folk had completely turned his head and transformed him from a shy, sensitive, aloof romantic to someone capable of writing such statements as the following to his brother: Well brother, I believe my fame is just now in its fullest flower. Everybody looks on me as a wonder of the world. If I but open my mouth the air resounds with what Dostoevsky said, what Dostoevsky means to do. . . . Bielinky declares Turgenev has quite lost his heart to me. ... All the Minnas, Claras, Mariannas, etc., have got amazingly pretty, but cost a lot of money.7 The reaction of his acquaintances to this sort of bombast was to nickname Dostoevsky "the literary pimple." Indeed, The Double commences with Golyadkin saying: "A fine thing if something un toward had happened today and a strange pimple had come up." Presumably his double was the "literary pimple" which erupted that day from within Golyadkin's personality. In spite of these considerations, The Double is not the portrayal of a genuine psychiatric phenomenon of paranoia, as Dostoevsky himself may have believed. While the feelings of persecution and the disowning of part of the self portrayed in The Double have psychiatric parallels in paranoid states, the experience of a hallu cinatory duplicate of the self is not explained by, or consistent with, a paranoid psychosis. The typical paranoid concept is one of a spot less self being unjustly blamed and tortured by evil others. In con trast, Dostoevsky's hallucinatory or semi-hallucinatory Doubles per secute their creators by asserting their identity with them, and usually their creators are aware that the Double is their "other self." Stavrogin says of his hallucinations (in the suppressed chapter of The Possessed): It shows different faces and characters yet it is always the same. I know it is different aspects of myself splitting themselves off yet it wants to be an independent devil so an independent devil it must be. Such self-awareness is quite ahen to the paranoid state. If the 351 This content downloaded from 186.55.26.0 on Fri, 12 May 2023 00:24:45 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms LAWRENCE KOHLBERG paranoid persecutors were to be experienced as duplicates of the self, the defensive function of the hallucinations would break down, since they would no longer protect the self against the awareness that it is the possessor of shameful impulses. Another "popular-psychiatry" concept often used by literary critics, the "split personality," is equally inadequate as an accurate interpretation of the Double phenomenon. This concept is suggested by Versilov in The Raw Youth who says: I am really split in two mentally, and I am horribly afraid of it. It is just as though one's second self were standing beside one; one is sensible and rational oneself, but the other self is compelled to do something per fecdy senseless and sometimes very funny; and suddenly you notice you are longing to do that amusing thing, goodness knows why. I once knew a doctor who suddenly began whistling in church, at his father's funeral. These divided selves of Dostoevsky do not, however, correspond to psychiatric notions of the "split personality." The most common psychiatric conception of the "split personality" refers to the hysteri cal phenomenon of multiple personalities, the Three Faces of Eve; each living a Jekyll and Hyde existence in independence of one another. Unlike such multiple personalities, the "selves" within any of Dostoevsky's figures are simultaneously aware of one another. These "split selves" have equally httle to do with schizophrenia, in the sense in which this has been misleadingly mistranslated as "split personality." Dostoevsky's consciously "split" characters do present classical symptoms of the obsessive-compulsive character, however. The "split" is not a separation of selves, it is an obsessive balancing or undoing of one idea or force with its opposite. Most character istically, a sacred idea compulsively arouses a degrading idea; the sacredness of the father's funeral compels the impulse to whist?e. The hero of Notes from Underground says, "At the very moment when I am most capable of feeling every refinement of all that is good and beautiful it would, as though by design, happen to me not only to feel, but to do, such ugly things." Not only impulse and counter-impulse, but belief and disbelief are opposed and simultaneously felt in a compulsion neurosis. Ac cording to Ivan's devil, "Some can contemplate such depths of belief and disbelief at the same moment that sometimes it really seems as if they are within a hairbreadth of being turned upside down." Psychoanalysts view these obsessional oppositions as represent ing conflicts derived from a battie of wills in early childhood, center 352 This content downloaded from 186.55.26.0 on Fri, 12 May 2023 00:24:45 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms The Doubles in Dostoevsky ing around training conflicts. According to Erikson s Childhood and Society, this conflict is between autonomy and shame or doubt. Shame, Erikson says, "is an emotion insufficientiy studied because in our culture it is so early and easily absorbed by guilt. Shame sup poses that one is completely exposed and conscious of being looked at, i.e. self-conscious. It is essentially rage turned against the self." The "Underground" man tells us: With an intense acute pang I was stabbed to the heart by the thought that ten years, twenty years, forty years would pass and even in forty years I would remember with loathing and humiliation those filthiest, most ludicrous, and awful moments of my life. No one could have gone out of his way to degrade himself more shamelessly, and I fully realized it, fully, and yet I went on. In the self-abasers, feelings of shame are responded to by further self-abasement, since such self-lowering debases and denies the others before whom shame is felt. Fyodor Karamazov says, "I feel when I meet people that I am lower than all and that they all take me for a buffoon, so I say let me play the buffoon for you are, every one of you, lower than I." The psychoanalytic notion of the obsessional character focused on a conflict between autonomy and shame helps us understand a very puzzling aspect of the literary structure of Notes from Under ground. The book is composed of two quite different parts: the first an ideological discussion, the second a presentation of some ex cursions in self-degradation. The ideological portion is an assertion of the need for free will, rational or irrational, against the rational determinism of Western scientific thought. The other half of the work is the expression of the "shame-humiliation syndrome." Some unity in these two parts of the book is provided by the emotional congruity of a personality type in whom the desperate need for freedom from domination or control is hnked to the cycle of shame and denial of others. This analysis of Dostoevsky's "split personalities" as related to obsessional ambivalence and shame does not direcdy aid us in un derstanding his Doubles. There is, however, a very direct psychiatric parallel to the kind of hallucination described in The Double. This parallel is the "autoscopic syndrome," a syndrome with no relation ship to paranoid states. A typical case is that of Mrs. A: Mrs. A returned home from her husband's funeral and when she opened the door to her bedroom, she immediately became aware of the presence of somebody else in the room. In the twilight she noticed a lady 353 This content downloaded from 186.55.26.0 on Fri, 12 May 2023 00:24:45 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms LAWRENCE KOHLBERG in front of her. Under the light she noticed that the stranger wore an exact replica of her own coat, hat, and veil. Mrs. A was neither surprised nor afraid and began to undress. The lady in black did exactly the same. Only then looking into the strangers face, did Mrs. A become aware that it was she herself, as if in a mirror, that it was her 'double,' her 'second self looking at her. She felt it was more alive and warm than she was her self. Feeling tired and weary, she lay down on her bed. As soon as she closed her eyes, the apparition disappeared. She felt stronger and when she opened her eyes, the apparition was not visible. Since that evening she had been visited almost daily by her 'astral body,' as she called it, mostly at dusk when she was alone. Of the double she says, 'In a detached intellectual way I am fully aware that my double is only a hallucination. Yet I see it; I hear it; I feel it with my senses. Emotionally I feel it as a living part of myself. It is me split and divided. It is all so confusing.'8 Almost everything Mrs. A says is echoed by one or another of Dostoevsky's Double-haunted figures. The physical details of the appearance of Dostoevsky's hallucinatory Double are very close to those described by autoscopic patients. Ivan's satanic Double has frozen in his trip through space, and is underdressed in summer clothes, though it is winter; autoscopic Doubles are typically cold, often described as bringing "a breeze of cold air." As in autoscopic experiences, Dostoevsky's Doubles appear at dusk or night, typically when the subject is alone in his bedroom. Like them, Dostoevsky's Doubles tend to be colorless, to be described in shades of grey. Surprisingly, the likelihood of Dostoevsky's having experienced the autoscopic syndrome has not been mentioned in the extensive psychological literature on Dostoevsky. Nevertheless, there is good reason to believe that he actually had these experiences. While the autoscopic syndrome is rare, it is often linked with severe epilepsy of the sort known to have affected Dostoevsky. The syndrome is extremely puzzling since it is found associated with a variety of con ditions, usually organic (epilepsy, parietal brain damage, and severe migraine) but occasionally purely emotional (schizoid personality, depressions). There is reason to beheve that an unusual number of writers have experienced autoscopic hallucinations. Maupassant definitely had hallucinations of a duplicate self in the middle stages of his syphilitic or paretic psychosis,9 hallucinations quite faithfully de scribed in Le Horla. Some writers without organic pathology defi nitely experienced the autoscopic syndrome, including Hoffman, de Musset, Richter and probably Poe.10 The phenomenon represents a projection of the body-image into space, or a loss of bodily coordi nates of the body image. The variations in reported emotional re 354 This content downloaded from 186.55.26.0 on Fri, 12 May 2023 00:24:45 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms The Doubles in Dostoevsky actions to autoscopic hallucinations are striking: sometimes satisfac tion, sometimes sadness, sometimes dread, sometimes indifference. There does not seem to be a single emotional meaning or genesis common to all cases of the autoscopic syndrome. While the psychi atric label provides a basis for understanding Dostoevsky's preoccu pation with Doubles, it does not seem to specify their meaning to him or to his novels. To cast further light on this problem, we must consider the variety of Doubles in Dostoevsky's other novels. We may best begin with some findings from a statistical study of Dostoevsky's char acters. Our study made use of a method called "Q technique,"11 de signed to bring some objectivity of inference into the analysis of the single case. Both Dostoevsky and his characters were rated on a large number of traits, both psychoanalytic and ideological. The results were factor analyzed to define types of character in relation to Dostoevsky's own personality. Undoubtedly this effort to control statistically the psychology which "cuts both ways" would cause its subject to repeat in anguish the famous statement in Notes from Underground about "hfe in the Crystal Palace": All human actions will then be tabulated according to these laws, mathematically, hke tables of logarithms. But man still is man and not the key of a piano and even if it were proved to him by science and mathe matics that he were nothing but a piano key, even then he would not be come reasonable but would purposely do something perverse simply to gain his point; if necessary, he will contrive destruction and chaos and sufferings and launch a curse upon the world. If you say all this, too, can be calculated and tabulated?chaos, darkness, and curses, so that the mere possibility of calculating it all beforehand would stop it all, and mathematical reason would reassert itself?then man would purposely go mad in order to be rid of reason and gain his point! The "chaos, darkness, suffering and curses" of Dostoevsky's char acters proved quite amenable to tabulation and defined very stable, clearcut types in the factor analysis. These types were the same (i.e., characters were divided into the same groups) whether psy choanalytic or ideological traits were used as the basis for type formation.12 The types which resulted are not hkely to make the conventional literary critic "defy mathematical reason," since they are not very different from those familiar in the Dostoevsky criticism. These types are defined by the entries in Table 1. As one reads down the table for a given type, the presence of a number indicates that this 355 This content downloaded from 186.55.26.0 on Fri, 12 May 2023 00:24:45 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms LAWRENCE KOHLBERG Table 1 Six Character-Type Factors Defined by the Loading of 34 Characters Upon Them Characters: Types: I II III IV VWill VI Bad Christ Self- Fern- Mur- Doubles Figures Abasers mines dere 1. Dostoevsky himself 43 28 31 Brothers Karamazov: 2. Fyodor (father) 70 3. Dmitri 58 4. Ivan 51 5. Alyosha 81 6. Smerdyakov 40 7. Grushenka 63 35 8. Katerina I. 70 9. Snegirov 74 10. Zossima (monk) 73 11. The Devil 74 The Idiot: 12. Myshkin 76 13. Rogozhin 65 14. Aglaia 72 15. Ippolit 54 45 16. Nastasya 45 Underground Notes: 17. Narrator 45 The Possessed: 18. Stavrogin 41 55 19. PyotrV. 58 20. Kirrilov 59 46 21. Shatov 71 22. Lisa D. 46 45 23. Stepan V. (father of P.) 64 The Double: 24. Golyadkin I 69 19 25. Golyadkin II 71 Crime and Punishment: 26. Katerina Marm. 52 51 27. Svidrigailov 61 28. Sonia 63 29. Dounia (sister) 40 45 30. Raskolnikov 54 31. Marmeladov 75 Psychiatric Types: 32. Paranoid 40 33. Hysteric 53 30 34. Psychopath 69 356 This content downloaded from 186.55.26.0 on Fri, 12 May 2023 00:24:45 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms The Doubles in Dostoevsky character is a representative of that type. The size of the number is an index of the "goodness" or purity of the character as a representa tive of the given type. The types defined in Table 1 are useful in sketching out the meaning of Dostoevsky's Doubles. The most unique of Dostoevsky's Doubles are hallucinations (Golyadkin II in The Double and the devils in The Possessed and The Brothers Karamazov). These hallu cinations persecute their flesh and blood counterparts by insisting on the fundamental identity of the two. These hallucinatory Doubles are all our Type I "bad Doubles," and they are imagined by our Type V "will murderers." Raters assigned high scores to Type I characters on the traits: "A mysterious and sinister affinity to another character," "Is a Double who is an intellectual inferior, a caricature of his alter-ego," "Is a persecuting Double." Type V characters tended to be rated high on the complementary traits, e.g., "Is perse cuted by a Double." A second type of Double is defined by the figures of Smerdyakov in The Brothers Karamazov and Pyotr Verkhovensky in The Pos sessed. These flesh and blood characters were distinct from the hallucinatory Doubles on the psychoanalytic traits but not the ideological. They are "psychopathic" figures who carry out murders wished for by the "paranoids" Ivan and Stavrogin, and are mysteri ous "half-brothers" to them. Still a third type of Double is represented by the Christ-figures of our Type II. These Christ-figures, with the exception of Sonia in Crime and Punishment, have alter-egos among our Type VI im pulsives. These relations, hke those last mentioned, are described in a terminology of "brother" and "sister," real or spiritual. Prince Myshkin has a mysterious affinity to Rogozhin and to Nastasya in The Idiot, both an attraction and a feehng of a hnkage of fate. Alyosha Karamazov is, in a somewhat similar sense, an alter-ego to his brother Dmitri who enacts sexual and aggressive impulses which Alyosha somehow shares. Dmitri tells him: I want to tell you now about the insects to whom God gave sensual lust. I am that insect, brother, and all we Karamazovs are such insects, and, angel as you are, that insect lives in you, too, and will stir up a tempest in your blood. Like Myshkin, Alyosha knows his impulsive Double will attempt murder, dreads it, but is strangely paralyzed or passive about pre venting it. In some sense, Type VI, the impulsives, seem to repre sent or enact the impulses of Type II, the Christ-figures, just as 357 This content downloaded from 186.55.26.0 on Fri, 12 May 2023 00:24:45 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms LAWRENCE KOHLBERG Type I figures enact the impulses of Type V, the "paranoid" will murderers. The relationship between Types I and V is exphcit and consciously intended by Dostoevsky, while the relationship between Type II and VI is much more cloudy and undefined. Our statistically derived map shows many clear-cut and recur ring aspects to Dostoevsky's Doubles. These are not the result of the requirements of structure of a particular book since they are repeated from novel to novel. They are also not explained, however, by mere knowledge that Dostoevsky may have experienced the auto scopic phenomenon. The autoscopic Doubles are assigned a definite evil personality constant from book to book and are in some mysteri ous way part of a world including good-and-evil, flesh-and-blood alter-egos. To enrich our notion of the meaning of these facts in relation to the autoscopic syndrome, we may turn to Otto Rank's discussion of "The Double as Immortal Self" in his last book, Beyond Psychology. No better example of the fact that "psychology is a knife which cuts both ways" can be provided than Rank's two writings on the Double. His first treatment is an orthodox psychoanalytic interpretation; his second written thirty years later is part of his own effort to form a theory which is "Beyond Psychology," i.e., beyond psychoanalysis. Rank's last discussion of literary Doubles is based on his postula tion of a universal striving for immortality or rebirth in man's non instinctual but irrational will. This striving is especially strong in the artist type, says Rank in Art and the Artist, since the urge to create is essentially the urge to immortalize the self. While the average individual takes himself as given, the artist (and the neu rotic who is essentially an artist manqu?) cannot. The artist is con tinually striving to remold his ego in terms of self-created ideals, in order to perpetuate or immortalize himself. This perpetually re created or reborn self is projected and justified in the art work. In Beyond Psychology, Rank also postulates the immortalizing tendency as underlying social ideologies and forms of social organi zation, through which the individual attains collective immortality. Rank believes that one point at which the individual, self-immortaliz ing needs of the artist intersect with collective ideologies is in the literary use of the Double. This literary use parallels genuine folk beliefs in many primitive cultures, as well as mythological themes. In these primitive cultures there is an equation of the individual's soul when alive, his ghost after death, and his actual shadow. This shadow-soul survives the individual's death, and may sometimes 358 This content downloaded from 186.55.26.0 on Fri, 12 May 2023 00:24:45 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms The Doubles in Dostoevsky leave the body in sleep, etc. There may, however, be some differ ences in appearance and character between the actual self and the ghostly Double. Rank points out that in modern hterature, the Double is usually a symbol of a character's past, his evil tendencies and his death rather than of future immortality, as in naive folk-beliefs. A typical example is E. T. A. Hoffman's Story of the Lost Reflection, in which the hero sells his mirror reflection (his "immortal soul") to a devil figure. This reflection takes on a life of its own and persecutes its former owner until the victim attempts to kill it and so kills himself. (Wilde's Picture of Dorian Grey presents a similar theme.) Rank explains the modern negative attitude toward the Double as due to modern man's over-rationalistic alienation from life and death and from his own fundamentally irrational will. Rank sees folk-beliefs and myths of the Double as related to the wide-spread mythology of twins. A common theme of myth is that of twins who have creative powers and who found cities and cul tures (e.g., Romulus and Remus). Often in these myths, one twin is killed by the other, or is killed in his place. Rank interprets this as indicating a concept of the twins as Doubles, one of whom becomes immortal and creative through the death of his mortal counterpart. According to Rank, primitive cultures see Doubles and twins as duplicate selves necessary for immortality, just as patriarchal cul tures see the son as a duphcate of the father, necessary for immor tality. Rank apphes these suggestive ideas to Dostoevsky's Doubles in only a vague, brief and superficial fashion. Their importance, how ever, is suggested by the clinical literature on the autoscopic syn drome.13 A number of the cases reported are like those of Mrs. A, cases in which the Double first appears immediately after the death of a significant person. In some sense the Double seems to be a sub stitute or resurrection of the lost person. In other cases, the Double represents, not a "resurrected self" but the self as dead. De Musset, just after walking through a cemetery, saw a hallucination of "a mysterious stranger which he recognized with terror as himself, twenty years older, with features ravaged by debauchery, eyes aghast with fear." A clinical case is reported of a woman in great anxiety, about to enter the hospital for surgical completion of a mis carriage, who was suddenly confronted by a realistic vision of her self lying in a coffin. This was the first appearance of a recurring mirror-like hallucination of a Double.14 359 This content downloaded from 186.55.26.0 on Fri, 12 May 2023 00:24:45 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms LAWRENCE KOHLBERG Our discussion suggests a close connection between Double or autoscopic experiences and epilepsy on the one hand, and concern about death and immortality on the other. Dostoevsky's extreme concern with death and immortality was expressed both in ideologi cal and in symptomatic behavior. On the ideological level, he wrote: "Without a superior idea, there cannot exist either the individual or the nation. But here on earth we have only one superior idea?the immortality of the soul because all other superior ideas have their source in this idea."15 On the symptomatic level, his fear of death was associated with his epileptic attacks. An attack was triggered off by passing a chance funeral procession. The association of death and epilepsy led him to fears of being buried alive, of being closed in for eternity. He would leave notes that he should not be buried for five days after an attack. His own Siberian sentence he viewed as a living burial after his near execution: "It is difficult to express how much I have suffered. These four years I look upon as a time of living burial. I was put in a coffin."16 These feelings suggest that he feared not only death, but his own ghosdy immortality in the face of his apparent death to the world. Dostoevsky told his friends that his epileptic attacks were asso ciated not only with fear of death and ghostly immortality, but with the joyful experiences of eternal hfe described by his epileptic fig ures Myshkin and Kirrilov. The association we would expect between epilepsy, experiences of immortality, and the Double phenomenon is found in the grouping of these traits in Dostoevsky's characters. A number of both the Type II good Doubles (Myshkin, Kirrilov, Alyosha) and the Type I bad Doubles (Smerdyakov) have epileptic or epileptic like seizures, while none of the other characters are portrayed as epileptic. In the good Doubles epilepsy is connected with a high rating on the trait, "Joyful experience in which eternal life is col lapsed into an instant." All the Type I good Doubles are rated high on the trait, "Lives for and believes in positive immortality." Of Alyosha, Dostoevsky says: "As soon as he reflected seriously, he was convinced of the existence of God and immortality and in stinctively said to himself: 'I want to hve for immortality and I will accept no compromise.' " If Dostoevsky's Type II good Doubles express his ideas, concerns and experiences of positive immortality, his Type I bad Doubles express his ideas and experience of negative immortality, of living 360 This content downloaded from 186.55.26.0 on Fri, 12 May 2023 00:24:45 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms The Doubles in Dostoevsky burial. Svidrigailov says: "We always imagine eternity as something beyond our conception, something vast. But why must it be vast? Instead of all that, what if it is one little room, like a bathhouse in the country, black and grimey and spiders in every corner, and that's all eternity is?" Dostoevsky intended this to be a reflection of his Siberian 'liv ing burial" and wrote of Crime and Punishment, "My Dead House was really most interesting. And here again shall be a picture of a hell, of the same kind as that 'Turkish Bath in the Prison' ( a chapter in the House of the Dead on the horrors of a multitude of naked, filthy bodies closely packed together in the prisoners' weekly steam bath)."17 Svidrigailov in Crime and Punishment and Stavrogin in The Possessed are flesh and blood characters who are sinister alter-egos to others. Both also experience hallucinations which are directly said to represent the ghosts or resurrections of dead or murdered per sons. In the passage on eternity just mentioned, Svidrigailov dis cussed his hallucinations of his dead wife Marfa (whom he has mis treated and probably murdered) and of a servant whom he drove to suicide. These hallucinations are not only experienced but believed in by Svidrigailov, who says, "I agree that ghosts only appear to the sick, but that only proves they are unable to appear except to the sick, not that they don't exist." Stavrogin also has two related sets of hallucinations (described in the suppressed chapter of The Possessed). One is of the devil, the other is of the twelve-year-old girl whom he seduced and led to suicide. At first sight, hallucinatory Doubles in the novels would seem to be one thing, and flesh and blood alter-egos another. The line of thinking we have pursued suggests, however, that the "living" bad Doubles may have a meaning similar to that of the "hallucinatory" bad Doubles. As in the case of Mrs. A, the Double is both a resur rection of a dead person and is the self. editor's note: Dr. Kohlberg plans an expanded version of this article which will be published in the book based on this issue. His longer article will consider more fully the relationship of the Dostoevskyan Doubles?in Crime and Punishment, The Possessed, The Idiot, and The Brothers Karamazov? both to literary structures and to the moral ideologies they convey. It will involve more directly psychoanalytic interpretations as well as a fuller 361 This content downloaded from 186.55.26.0 on Fri, 12 May 2023 00:24:45 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms LAWRENCE KOHLBERG statistical treatment. The preliminary findings are striking. The hallucina tory devil appears to be, according to Dr. Kohlberg's factor analysis, a resurrection of the murdered father. Psychoanalytically, the hallucinatory Doubles represent evil masculine sexuality, expressed in the defilement of young girls, while the "twin Doubles" represent a masculine identification on "an unnatural homosexual rather than on an unnatural heterosexual base." The "good Doubles" are Christ figures, whose major identification is with the shame and suffering of women, which they share but for which they feel guilty. These psychoanalytic meanings appear to clarify the sequences of appearances of the Doubles, as well as Dostoevsky's ideology of vicarious guilt and suffering. References 1. P. C. Squires, "Fyodor Dostoevsky, A Psychopathographical Sketch" in Psy choanalytic Review, 24 (1937), pp. 365-388. 2. Sigmund Freud, "Dostoevsky and Parricide" in Collected Papers, Vol. V (London: Hogarth, 1950). 3. Smith and Isotoff, "Dostoevsky: the Abnormal from Within" in Psycho analytic Review, 22 (1935), pp. 385-403. 4. Edna C. Florance, "The Neurosis of Raskolnikov; A Study in Incest and Murder" in Archives of Criminal Psychodynamics, 1 (1955), pp. 344-396. 5. E. Kris, Psychoanalytic Exploration in Art (New York: International Uni versity Press, 1952), Chapter 1. This chapter provides a good summary of recent psychoanalytic "ego-psychology" approaches to literature. 6. Otto Rank, "Der Doppelg?nger" (Vienna: Internationale Psychoanalytische Verlag, 1925). Translated into French as "Don Juan, une ?tude sur le double" (Paris, 1932). 7. The Letters of Fyodor Dostoevsky (New York: Horizon, 1961). 8. N. Lukianowicz, "Autoscopic Phenomena" in Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry, 80 (1958), p. 199. This article is perhaps the best summary of clinical data on this phenomena, along with Reference 10. 9. S. Coleman, "The Phantom Double, Its Psychological Significance" in British Journal of Medical Psychology, 14 (1934), pp. 254-273. 10. J. Todd and K. Dewhurst, "The Double: Its Psychopathology and Psycho physiology" in Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases, 122 (1955), pp. 47-56. 11. W. Stephenson, Q Technique: The Study of Behavior (Chicago: Univer sity of Chicago Press, 1953). 12. The detailed methods and results of this study will be reported in a pro fessional psychological journal. 13. Lukianowicz, op. cit. 14. Todd and Dewhurst, op. cit. 15. Diary of a Writer (New York: Braziller, 1954). 16. The Letters of Fyodor Dostoevsky. 17. Loc. cit 362 This content downloaded from 186.55.26.0 on Fri, 12 May 2023 00:24:45 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms