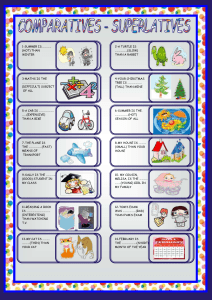

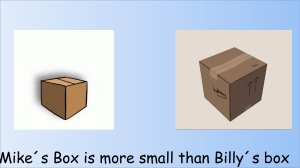

C l i n i c a l E v a l u a t i o n o f th e F e l i n e N e u ro l o g i c P a t i e n t Amanda R. Taylor, DVM a, *, Sharon C. Kerwin, DVM, MS b KEYWORDS Seizures Myelopathy Encephalopathy Cat KEY POINTS Efficient, gentle, and safe handling of cats can result in complete neurologic evaluations and accurate neuroanatomic localizations. The clinic environment should facilitate the examination by providing a quiet and secure environment for the cat. When direct examination of a cat is not possible, the practitioner should fully use indirect methods of examination and video recordings of cat behavior or clinical signs. Direct examination of a cat should proceed in a logical order, where the most useful tests are performed early on in the examination. Video content accompanies this article at http://www.vetsmall.theclinics.com. INTRODUCTION Animals with neurologic disease can be challenging for any practitioner. This task may seem even more daunting when the patient is a cat. As a result, veterinarians’ level of stress in dealing with these patients and the emotional environment they create for their patients, themselves, their staff, and clients can set up failure or success. A few accommodations in preparation for cat examinations and adaptations in the neurologic evaluation can result in a successful visit that is defined by low stress, accurate neuroanatomic localization, and appropriate diagnostic plan. The preparation of the clinic, staff, and doctors involves developing an understanding of the unique qualities of feline behavior and altering the environment, handling, and examination accordingly. Cats with neurologic disease may present additional obstacles due to the relative lack of tolerance for the length of and restraint in classic veterinary neurologic evaluations. The authors have nothing to disclose. a Department of Clinical Sciences, Auburn University College of Veterinary Medicine, Auburn, AL 36849, USA; b Department of Small Animal Clinical Sciences, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA * Corresponding author. E-mail address: art0022@auburn.edu Vet Clin Small Anim 48 (2018) 1–10 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cvsm.2017.08.001 0195-5616/18/ª 2017 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. vetsmall.theclinics.com 2 Taylor & Kerwin In the authors’ experience, examination of the neurologic cat has key differences, such as limiting repetition, using tests that are reliable, and focusing the examination on what is most likely to yield results that determine a neuroanatomic localization. The authors’ practical steps to preparing for the examination and the indirect and direct components of the examination in the cat are discussed. GOALS OF THE EXAMINATION 1. Provide an environment and handling techniques that promote a low-stress interaction 2. Using indirect techniques whenever possible 3. Acquiring information from the cat using minimal handling and restraint 4. Localizing the neuroanatomic lesion PREPARATION STRATEGIES The Nature of the Cat The inherent nature of feline patients is that of a solitary hunter that fights as a last resort if flight from a confrontation is unsuccessful or not possible. Veterinarians are in control of many factors in the veterinary clinic that could result in a cat identifying a need to run or confront. These include noise level, odors, quick movements, presence of other species such as dogs, the brightness of a room, brusque or aggressive handling, and agitated handlers. Even when the best prevention strategies are used, cats may still display behavior that indicates they are threatened.1,2 Clinic Admission Although a trip in the car can be a joyous occasion for a dog that could result in a trip to a lake or dog park, cats are unlikely to be in a car at any time other than when they visit a veterinarian. They are not conditioned to being placed in a carrier and transported. By the time cats arrive at a veterinarian’s office, they may already be in some state of stress from the car ride to the clinic. The additional stimuli of a visit to the hospital from the noises, smells, and other elements encountered in the lobby of a clinic can be of further threat to a cat. To limit the negative factors that can detract from the visit, several steps should be taken: 1. Discuss with clients that all cats must be in their own carrier at the hospital and cannot be removed from the carrier until they are moved to the examination room. 2. Allow more time for appointments where the chief complaint is consistent with neurologic disease. 3. Provide a separate waiting area and entrance for cats when possible. 4. Guide the client and cat into an examination room as quickly as possible if a separate waiting area is not available. 5. Maintain 1 or 2 examination rooms that are for feline patients only. 6. Control the light, odor, and noise in the room by providing soft light, synthetic feline facial pheromone analogue, and keep the doors closed. 7. Provide equipment in the examination room to make the cat more comfortable, such as a thick towel on the examination table, catnip, laser pointers, cat treats, and toys.1–6 Recognition of Feline Behavior A well-trained veterinary team can recognize when a cat is fearful or combative and can change an approach when these signs are first identified, rather than reacting after Feline Neurologic Patient a cat has acted in a defensive and aggressive manner. Experienced cat handlers carefully observe a cat’s facial expression, tail movement, and body posture. When cats identify a threat, they may display mydriasis, whiskers flattened toward the face, wide opening of the eyes, and a general tightening of the muscles of facial expression. The ears change from their normal erect posture to a rostral tilt and to a gradual flattening. The tail may begin to twitch or flick back and forth. A stressed cat has postures, such as arching of the back, bringing the head down toward the ground, and pulling the feet close to the body. Identification of any of these changes in the cat should cause an examiner or handler to either change tactics in handling or take a break in interaction. If a cat does not display warning signs or if these signs are not recognized, more aggressive behavior from the cat can result. This includes further arching of the back, narrowing of the pupils, and finally vocalization, striking out with the front feet, or attempting to bite the veterinarian or handler. When any of these signs is recognized, the cat should be allowed a respite from the examination or the examination should be concluded.1,2 Client Education Cat owners are often astute and in tune with their pets. Some of the tests performed during neurologic examination can appear strange or even scary to a client, not to mention the negative reactions these tests may elicit from the cat. The authors have been most successful in performing feline examinations for neurologic disease when explaining what will occur to clients prior to performing an examination. The authors explain to the clients that if a cat indicates that the examination is too stressful, the examination will cease and observing the patient will be continued. Open communication with clients prior to examination creates a partnership between client and veterinarian that facilitates the other aspects of a cat’s treatment and diagnostics. INDIRECT PATIENT EVALUATION STRATEGIES During neurologic examination of a dog, an examiner may repeat tests multiple times and come back to the same test more than once, but cats are often less tolerant of this technique in examination. The order of the examination listed herein is how the authors proceed unless, as they begin to evaluate the case, a cat becomes intolerant of the examination. Should this occur, the order of the examination is changed to prioritize the most helpful tests or a break is taken; for example, cats presenting for seizures indicate they will not tolerate much examination after indirect evaluation. In this case, the authors initially limit the examination to evaluation of cranial nerves followed by postural reactions. If these initial tests were tolerated, other elements of the examination could be completed. The authors attempt to move through the examination with efficiency and safety. If there is an abnormality that needs to be reassessed and the cat is tolerating examination, this portion of the examination is revisited after other tests are complete. Video Recording Any cat presenting for a possible neurologic disease should undergo a neurologic examination, but there are some that do not tolerate nor participate. In these cases, it is necessary to base diagnostic and therapeutic plans on historical findings, indirect observations, and, when available, video of the cat in the home environment. One of the most helpful ways to supplement the information gained from the history is to ask owners to video record their observations. Because many clients own smart phones with this capability, this is a practical request. The client can record video before the appointment, or if the examination is unsuccessful the client can send video to 3 4 Taylor & Kerwin the veterinarian at a later time. Even in the most tolerant cats, the changes or problems observed by the client may not be displayed at the clinic. In these cases, video of the cat at home may allow a veterinarian to see the cause of a client’s concern. Primary veterinarians seeking consultation with a neurologist or other specialist for assistance with a case can also use video from the client or from the examination in the clinic. Mentation Key history questions can enable a veterinarian to learn what a cat’s mentation is like at home. These include open-ended questions, such as: How does your cat’s temperament now compare to 6 months ago? What does your cat enjoy the most in life? and How does your cat normally interact with you and/or your family/spouse/significant other? Once a cat has been taken to an examination area, the front of the cage should be opened to allow the cat to exit if it is willing. Alternatively, the top of the carrier can be removed and the cat can explore its surroundings. The history of the cat is discussed while the cat is left alone to allow it time to feel comfortable to exit the carrier. It may take quite some time for the cat to decide to exit the carrier, up to 10 minutes in the authors’ experience. In some cases, the cat does not participate in this way. The cat can be gently lifted from the carrier (once the lid has been removed) and placed on the floor away from the carrier to observe its interactions with the environment. Forcing a cat from its carrier by pulling it through the door of the carrier can result in abnormal behavior and unnecessary stress for the patient and is therefore discouraged.1,2 Posture Posture is concurrently assessed with gait and mentation. Common abnormal postures seen include head tilts and turns, ventroflexion of the neck and plantigrade stance (Fig. 1). The cat must be carefully observed to determine whether it has low head carriage secondary to fear or weakness. A weak cat does not move the head often and the nose of the cat may point ventrally, whereas a fearful cat pulls the head in toward the body and the nose is pointed away from the tail with the nose pointed forward. Plantigrade stance can be difficult to determine in a cat that is uncomfortable in the clinic and is walking carefully around the room or choosing not to walk. Nervous or scared cats tend to have all 4 feet lowered and pulled in close to the body. Gait Challenges with gait evaluation arise when a cat is fearful, because these cats stay as low to the ground as possible when walking or crouch in one place and are reluctant to Fig. 1. Cats displaying common abnormal postures: head tilt (A), head turn (B), and concurrent ventroflexion of the neck with plantigrade stance (C). Feline Neurologic Patient move. Gait should always be evaluated on a surface with good traction in a room that is closed off to ensure the cat’s safety. In cats with abnormal gait, the femoral pulses should always be evaluated if the pelvic limbs are affected (generally done prior to neurologic examination) and an orthopedic examination performed (generally after neurologic examination because direct orthopedic examination may hinder appropriate neuroanatomic localization due to lack of patient compliance with extensive examination). The following questions should be run through when evaluating the gait to determine if there is a neurologic cause of abnormal gait: 1. Is the cat off-balance (ataxic)? Cats may display proprioceptive (crossing over of the limbs or scuffing of the dorsal surface of the paws), vestibular (circling or falling), or cerebellar ataxia (hypermetria and intention tremors). 2. Does the cat appear weak in a limb (plantigrade or palmigrade stance)? 3. Is there lameness associated with the gait (off-loading of weight seen as a short stride in a limb, head bob, or hike of a hip dorsally when walking)? 4. What is the length of the steps the cat is taking (long strides with a delay in forward movement can indicate proprioceptive deficits; short strides can indicate lameness or a lower motor neuron lesion)? 5. Can you hear scuffing of the dorsal aspect of the paws when you listen to the gait (this is most often an indication of proprioceptive deficits)? Several techniques can be used to encourage ambulation in the cat in a gentle manner. 1. Laser pointers a. A cat’s attraction to the light of a laser can cause a previously reluctant cat to follow the light on the floor. b. Following a laser pointer may cause a previously unobserved intention tremor to be elicited. 2. Carrier a. A cat may think the carrier is a safe place to hide from the examiner. b. Place the carrier at the opposite end of the room from the cat on the ground, the cat may walk to it. c. Some cats follow a person carrying the carrier across the room. 3. Step stool a. A step stool less than two feet tall can cause a cat to move. b. Place the cat on top of the stool. c. Most cats jump down and walk away from the stool. d. If a cat is unwilling to jump down, place a hand over the dorsum or behind it and gently nudge it forward. DIRECT PATIENT EVALUATION STRATEGIES Handling and Restraint A cat cannot be forced into undergoing an examination if the goals are to get accurate results and not harm the cat. The more a cat is made to participate when displaying signs of stress, the more likely a negative or aggressive response is elicited from the cat, resulting in an end to the examination, harm to the cat, or harm to the examiner or handler. Rough handling, such as loudly verbally scolding, scruffing, or muzzling the cat, is likely to result in undesired responses from the cat. Physical contact with a cat during the examination should proceed quietly and slowly, always with the first approach to the cat over the back of the head or the neck and never with a quick approach to the cat’s face. 5 6 Taylor & Kerwin The authors have spent considerable time in investment on the education of their staff in appropriate handling techniques. Implementation of a team approach is the basis for a successful neurologic examination being completed. Acceptable restraint techniques include the use of sturdy Elizabethan collars (the authors prefer reusable collars that snap into place), thick towels, and patience for the cat (Fig. 2). If a cat does not tolerate examination, an indirect approach consisting of observation is recommended. Prioritization of Examination The order of an examination can be changed and prioritized based on observations made during the indirect examination. If a cat displays signs that direct handling will not be tolerated for long, as discussed previously, the examination can be prioritized by first determining whether or not the gait of the cat is abnormal. Although this method is not failsafe, it can ensure that the most information is gained prior to having to end the examination. Cranial Nerves Frightened or stressed cats may not have normal responses to cranial nerve testing, regardless of whether they have neurologic deficits, resulting in false-negative examinations (Table 1).7–12 Therefore, the authors usually test cranial nerves prior to other direct neurologic assessment. A cotton-tipped applicator may be used instead of a finger to perform many of the cranial nerve tests in the cat. All the tests may be performed while a cat is wearing a sturdy Elizabethan collar, should that be necessary for patient and examiner safety. An assessment of facial symmetry is made prior to performing any of the tests discussed later. When possible, the authors recommend performing assessment without touching the cat, because facial expression may change drastically in response to human touch. In the authors’ experience, menace is more reliably assessed when a cat is minimally stressed; therefore, menace is the first direct cranial nerve reflex performed. One eye is covered while the other is assessed as tolerated by the patient. If a cat does not initially respond to a menacing gesture, a gentle tap at the medial and lateral canthus of the eye (which also serves as the palpebral test) may cause a cat to respond to menace testing appropriately. Normal cats often incompletely close their Fig. 2. Profile (A) and front view (B) of a cat restrained in a reusable Elizabethan collar for examination. Performance of hopping testing in cat with Elizabethan collar (C). Feline Neurologic Patient Table 1 Cranial nerve tests Cranial Nerve Test Afferent Arm Efferent Arm Menace CN II CN VII Pupillary light reflex CN II CN III Palpebral reflex CN V CN VII Sensation, face CN V CN VII Gag CN IX CN X Physiologic nystagmus Vestibular apparatus CNs III and VI Abbreviation: CN, cranial nerve. eyes in response to this test. Although a canine patient’s reliable interest in cotton balls allows for visual tracking, most cats seem to be less interested in cotton ball testing and the authors have not found this reliable for assessment of vision. Palpebral reflex is assessed after menace by gently tapping the medial and lateral canthus of each eye to elicit a blink, often with a cotton-tipped applicator for the safety of the examiner. Physiologic nystagmus can be more difficult to elicit and assess in a cat by turning the head from side to side. In cats of calm temperament, it is most helpful for an examiner to pick up a cat, and, with it facing the examiner, the examiner twists his/her body from side to side at the waist, moving the cat with him/her and observing its eyes for movement (Video 1). The cat’s eyes should quickly move in the direction the examiner is turning. An evaluation for positional strabismus is performed by swiftly lifting the head and checking the globes for lack of central position of the iris. Facial sensation is assessed by touching either side of the maxilla, mandible, temporal region, and medial nasal mucosa. The cat should respond by blinking or consciously responding to the sensation with turning the head or body away from the stimulus, vocalization, or other responses. Assessment of a cat’s gag reflex can be performed directly by touching the caudal pharyngeal wall with a finger, generally the index finger. In patients where it is not believed this will be tolerated, pressure can be externally placed on/rub the pharyngeal region and patient observed for swallowing and licking. Pupillary light reflex is assessed by shining a strong light in 1 pupil and observing both irises for constriction. Fearful cats may have pupils that are mydriatic at rest and less responsive to pupillary light reflex assessment due to increased sympathetic tone; however, direct and indirect responses should still be present. Postural Reactions The authors’ evaluation of postural reactions begins with utilization of the same step stool that was discussed previously regarding gait evaluation. When a cat jumps down from the stool, if there are deficits in the proprioceptive system, the cat may stumble when it lands. When performing postural reaction testing in dogs, the authors almost always start with knuckling, followed by hopping and other tests, such as wheelbarrowing. In the cat, however, the authors typically perform 1 or 2 methods of postural reaction testing: hopping (most reliable) or tactile placing where the patient is brought to the edge of the table and allowed to place 1 paw at a time on the surface of the table. Knuckling is typically not performed because the reaction in most cats is withdrawal of the limb and inability for an examiner to place the dorsal surface of the paw on the ground. Although some examiners may find knuckling to be a helpful test 7 8 Taylor & Kerwin by observing whether the cat places its paw on the surface normally, the authors find that the cat examined may become agitated by having its feet touched repetitively during knuckling. Segmental Reflexes In a classic neurologic examination of a companion animal, the patient is restrained in lateral recumbency to perform segmental reflexes (Table 2).7–12 This technique is often unsuccessful in the cat. To keep a cat in lateral recumbency, the necessary degree of restraint can result in the cat no longer tolerating examination. Therefore, the authors recommend segmental reflexes should be performed with the cat either standing or in extremely tolerant cats on their back in the lap of the examiner. The initial assessment is limited to the flexor withdrawal reflexes of all limbs and patellar reflexes because the authors have found the other reflexes to be unreliable in performance and interpretation. After these initial segmental reflex tests, cutaneous trunci and perineal reflex are assessed in the standing cat. Other reflexes are assessed in some cases, such as cranial tibial, gastrocnemius, triceps, extensor carpi, and biceps reflexes. For example, a cat with monoparesis of a pelvic limb might have all the pelvic limb reflexes assessed. Nociception Testing Nociception testing is only performed in cats with absent voluntary motor function.7–12 If voluntary motor function is present, the degree of dysfunction of the spinal cord or nerves is not severe enough to result in loss of sensation and, therefore, does not warrant nociception testing. The interdigital webbing of the affected limb is tested for superficial nociception by compression with fingers (first) or hemostat forceps (second if no response to digital pressure). The cat is observed for a conscious response to the stimulus, such as turning of the head, vocalization, or attempts to bite. If superficial nociception is absent, deep nociception is tested by cross-clamping a digit of the affected limb with hemostat forceps. Hyperesthesia Detection and Palpation While the cat is standing, gentle palpation is performed to detect head pain and paraspinal discomfort. Gentle pressure is placed on head using the thumb and middle finger in the temporal region, as if picking up a 6-pack. Palpation of the paraspinal Table 2 Segmental reflexes Reflex Spinal Cord Segments Flexor withdrawal, thoracic limb C6–T2 Biceps C6–8 Triceps C7–T2 Extensor carpi radialis C7–T1 Flexor withdrawal, pelvic limb L4–S2 Patellar L4–L6 Gastrocnemius L6–S2 Cranial tibial L6–L7 Cutaneous trunci C8–T1 (efferent), T3–L3 Perineal S1–S3 Feline Neurologic Patient musculature is performed with mild pressure placed with the index and middle finger of the dominant hand on the epaxial muscles on dorsal midline proceeding from caudal to cranial. The cervical region is slowly put through a range of motion to detect for resistance or painful reactions from the cat. If initial gentle palpation does not elicit a response, firm pressure is applied and the tests repeated. Although cessation of panting can be a reliable sign of pain in the dog, cats have other indications. Observed changes include flattening of the ears, lowering of the head, or a sudden contraction of the epaxial muscles tested. Typical responses, such as vocalization, turning of the head, and other behaviors, may also be seen. SUMMARY Efficient, gentle, and safe handling of cats can result in complete neurologic evaluations and accurate neuroanatomic localizations. The clinic environment should facilitate the examination by providing a quiet and secure environment for the cat. When direct examination of a cat is not possible, the practitioner should fully use indirect methods of examination and video recordings of cat behavior or clinical signs. Direct examination of a cat should proceed in a logical order where the most useful tests are performed early on in an examination. Should a cat become intolerant of examination, the practitioner should conclude the handling of the cat. SUPPLEMENTARY DATA Supplementary data related to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.cvsm.2017.08.001. REFERENCES 1. Rodan I, Sundahl E, Carney H, et al. AAFP and ISFM feline-friendly handling guidelines. J Feline Med Surg 2011;13(5):364–75. 2. Rodan I, Heath S. Feline behavioral health and welfare. St. Louis (MO): Elsevier Health Sciences; 2015. 3. Kronen PW, Ludders JW, Erb HN, et al. A synthetic fraction of feline facial pheromones calms but does not reduce struggling in cats before venous catheterization. Vet Anaesth Analg 2006;33(4):258–65. 4. Pereira JS, Fragoso S, Beck A, et al. Improving the feline veterinary consultation: the usefulness of Feliway spray in reducing cats’ stress. J Feline Med Surg 2016; 18(12):959–64. 5. Frank D, Beauchamp G, Palestrini C. Systematic review of the use of pheromones for treatment of undesirable behavior in cats and dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2010;236(12):1308–16. 6. Gunn-Moore DA, Cameron ME. A pilot study using synthetic feline facial pheromone for the management of feline idiopathic cystitis. J Feline Med Surg 2004; 6(3):133–8. 7. De Lahunta A, Glass EN, Kent M. Veterinary neuroanatomy and clinical neurology. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2014. 8. Dewey CW, da Costa RC. Practical guide to canine and feline neurology. John Wiley & Sons; 2015. 9. Garosi L. Neurological lameness in the cat: common causes and clinical approach. J Feline Med Surg 2012;14(1):85–93. 10. Lorenz MD, Coates J, Kent M. Handbook of veterinary neurology. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2010. 9 10 Taylor & Kerwin 11. Fingeroth JM, Thomas WB, editors. Advances in intervertebral disc disease in dogs and cats. John Wiley & Sons; 2015. 12. Garosi L. Neurological examination of the cat: how to get started. J Feline Med Surg 2009;11:340–8.