walter benjamin selected writings volume-1

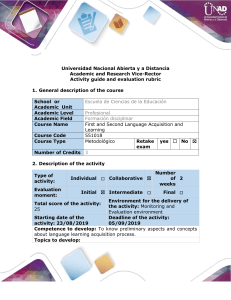

Anuncio