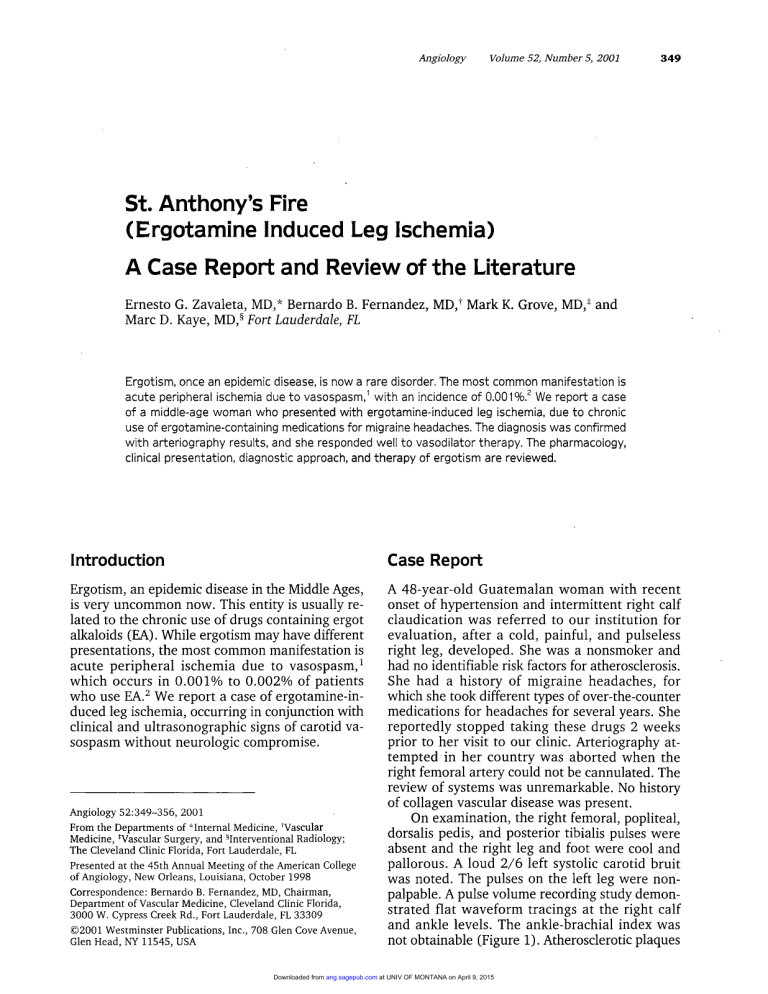

349 St. Anthony’s Fire (Ergotamine Induced Leg Ischemia) A Case Report and Review of the Literature Zavaleta, MD,* Bernardo B. Fernandez, MD,† Mark K. Grove, MD,‡ and Kaye, MD,§ Fort Lauderdale, FL Ernesto G. Marc D. Ergotism, once an epidemic disease, is now a rare disorder. The most common manifestation is acute peripheral ischemia due to vasospasm, 2 We report a case 1with an incidence of 0.001%. of a middle-age woman who presented with ergotamine-induced leg ischemia, due to chronic use of ergotamine-containing medications for migraine headaches. The diagnosis was confirmed with arteriography results, and she responded well to vasodilator therapy. The pharmacology, clinical presentation, diagnostic approach, and therapy of ergotism are reviewed. Introduction Case Report epidemic disease in the Middle Ages, This entity is usually related to the chronic use of drugs containing ergot alkaloids (EA). While ergotism may have different presentations, the most common manifestation is1 acute peripheral ischemia due to vasospasm, which occurs in 0.001% to 0.002% of patients who use EA.2 We report a case of ergotamine-induced leg ischemia, occurring in conjunction with clinical and ultrasonographic signs of carotid vasospasm without neurologic compromise. A Ergotism, is very an uncommon now. Angiology 52:349-356, 20011 From the Departments of *Internal Medicine, 1 Vascular Medicine, ’Vascular Surgery, and ~Interventional Radiology; The Cleveland Clinic Florida, Fort Lauderdale, FL Presented at the 45th Annual Meeting of the American of Angiology, New Orleans, Louisiana, October 1998 College Bernardo B. Fernandez, MD, Chairman, Department of Vascular Medicine, Cleveland Clinic Florida, 3000 W. Cypress Creek Rd., Fort Lauderdale, FL 33309 ©2001 Westminster Publications, Inc., 708 Glen Cove Avenue, Glen Head, NY 11545, USA Correspondence: 48-year-old Guatemalan woman with recent of hypertension and intermittent right calf onset claudication was evaluation, after referred a to our institution for cold, painful, and pulseless right leg, developed. She was a nonsmoker and had no identifiable risk factors for atherosclerosis. She had a history of migraine headaches, for which she took different types of over-the-counter medications for headaches for several years. She reportedly stopped taking these drugs 2 weeks prior to her visit to our clinic. Arteriography attempted in her country was aborted when the right femoral artery could not be cannulated. The review of systems was unremarkable. No history of collagen vascular disease was present. On examination, the right femoral, popliteal, dorsalis pedis, and posterior tibialis pulses were absent and the right leg and foot were cool and pallorous. A loud 2/6 left systolic carotid bruit was noted. The pulses on the left leg were nonpalpable. A pulse volume recording study demonstrated flat waveform tracings at the right calf and ankle levels. The ankle-brachial index was not obtainable (Figure 1). Atherosclerotic plaques Downloaded from ang.sagepub.com at UNIV OF MONTANA on April 9, 2015 350 Figure 1. Pulse volume recording results showing flat waveforms in the right calf and ankle. The ankle/brachial index was unobtainable since no pressure could be measured in the right ankle. during duplex ultrasound imaging right iliac, common femoral, and superficial femoral arteries. A duplex ultrasound of the were not seen of the carotid arteries demonstrated increased velocities consistent with bilateral 60% to 79% stenosis. No discreet plaques were discerned at the bifurcation. Westergreen sedimentation rate and complete blood cell counts were normal, raising the suspicion of ergotamine abuse. This was confirmed when the patient admitted that some of the medications that she took for her migraine headaches contained ergotamine derivatives and caffeine. Hypercoagulable studies and antinuclear antigen profile were also normal. Arteriography was performed via the contralateral femoral artery. Initial films of the right lower extremity demonstrated severe stenosis of the superficial femoral artery and small collateral vessels from the profunda femoris artery (Figure 2A). The tibial vessels could not be identified (Figure 2B). Following the initial runoff, 100 Ag nitroglycerin was injected intraarterially into the right femoral artery. Repeat arteriography was performed 5 minutes following the injection of nitroglycerin and showed marked improvement of the stenosis in the common femoral, superficial femoral, deep femoral, and popliteal arteries (Figure 3A). The tibial vessels were seen, and three-vessel runoff to the foot was seen (Figure 3B). The patient was admitted to the hospital for further treatment. She received intravenous ni- troprusside for 48 hours in conjunction with heparin infusion, oral calcium channel blocker (nifedipine), and alpha blocker (prazosin) that resulted in prompt return of pedal pulses and resolution of symptoms. Results of the physical examination following therapy were normal, and the carotid bruit disappeared. Follow-up pulse volume recording and the ankle brachial-index were normal (Figure 4). Serum ergotamine levels measured on admission to the hospital were undetectable. Discussion The first references to ergot alkaloid intoxication due to ergot-tainted rye is found on an Assyrian Downloaded from ang.sagepub.com at UNIV OF MONTANA on April 9, 2015 351 Figure 2. A. Initial runoff of the arterial circulation on the right thigh, revealing severe stenosis of the superficial femoral artery and multiple small collateral vessels from the profunda femoris artery. B. The tibial vessels were not seen during the initial runoff of the right leg. Few small collateral vessels are present. 3. A. After intraarterial injection of nitroglycerin, the spasm in the superficial femoral marked shows improvement. The small collateral vessels from the profunda femoris artery are artery no longer visible. B. Following injection of nitroglycerin, the tibioperoneal vessels are now visible. Figure Downloaded from ang.sagepub.com at UNIV OF MONTANA on April 9, 2015 352 Figure volume Follow-up pulse recording after 4. with vasodilator The waveforms and therapy. the ankle/brachial index show marked improvement. treatment dating from 600 BC. In the Middle Ages, epidemics of &dquo;gangrenous ergotism&dquo; were common in Europe due to ingestion of rye contaminated with the ergot fungus Claviceps purpurea. Claudication and painful burning of the affected tablet limb occurred in less advanced cases. The disease called Holy Fire or St. Anthony’s fire, the latter being in honor of the saint at whose shrine re- was said to be obtained.’ The frequency of epidemics declined after the relationship with the contaminated rye was recognized. lief was Pharmacology Ergot alkaloids can be divided in three categories: amino-acid alkaloids (ergotamine), amine alkaloids (ergonovine), and dihydrogenated amino acid alkaloids.3The first oxytocic properties, two groups have direct can cause vasoconstriction, central emetic effect. Ergotamine, in particular, increases peristalsis of the gastrointestinal tract. 3,4 Those in the first group are also alpha-adrenergic blocking agents and can cause vasodilatation by inhibition of norepinephrine-induced vasoconstriction. 4,5 Dihydroergotamine is and have a synthesized by hydrogenation of the alkaloids. This modification increases the alpha-adrenergic blocking effect and decreases the vasoconstrictor and emetic effects.5 The major pharmacologic effects of EA include smooth muscle stimulation (most evident as vasoconstriction and uterine contraction), central sympatholytic activity, and peripheral alpha- adrenergic blockade.66 Ergot-containing products interact with multiple receptors, such as norepinephrine, epinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin receptors. They cause vasoconstriction by stimulating alphaadrenergic and 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) receptors, which is responsible for the development of ischemic side effects.5 While ergot alkaloids are poorly absorbed orally (less than 2%), the concentration required to produce appropriate pharmacologic effects is very low. Absorption via the rectum has been shown to be more complete. 4,7 Contrasting with a rapid clearance of the administered drug from the plasma, a protracted effect of the EA in the vasculature has been documented and this appears to be a characteristic property of EA.’-11These Downloaded from ang.sagepub.com at UNIV OF MONTANA on April 9, 2015 353 findings suggest that an extremely slow dissociation from the receptor sites and/or the presence of active metabolites may account for the proof action of these compounds in longed duration the periphery.88 Ergot alkaloids and their metabolites are primarily metabolized in the liver ( > 90%) and are excreted in the feces via biliary elimination. Only a small fraction of these drugs is excreted through the renal system.’ Several drugs with hepatic metabolism have been reported to increase the potential for ergotism associated with ischemic complications. The use of macrolide antibiotics, oral contraceptives, and ampicillin has been associated with cases of ergotism. 12-14 Beta blockers can increase the risk of severe peripheral ischemia with concomitant EA administration due to inhibition of beta-2 receptor-mediated vasodilatation.l5 Smoking has also been reported to increase the incidence/likelihood of ergot-induced peripheral ischemia. 12 Ergotamine-Induced Vasoconstriction Ergotism is a rare disorder that may be associated with the use of ergot derivatives either at therapeutic doses (iatrogenic) or with chronic abuse. The incidence of ergotism is estimated to be 0.001%-0.002% in patients using ergotamine preparations for migraine headaches, for postparturition hemorrhage, or in combination with heparin for deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis.22 Ischemic manifestations can occur in any part of the circulatory system. Symptoms secondary to arterial spasm and ischemia induced by ergotamine have been reported in the brachial,4,15-17 radial, 15 iliac,18~19 femoral, 6,12,15,18,20 coronary, 21,22 renal,23 popliteal, 6,18 mesenteric,24 retinal,6and carotid arteries.25,26 Ergotamine intoxication can be principally observed in three conditions: (a) acute intoxica(b) acute intoxi- tion via an allergic mechanism; cation via the use of high doses of ergot derivatives ; or (c) chronic intoxication after prolonged therapy at therapeutic doses, 1,17 the latter being the presentation. ergotism may be manifested by nausea, vomiting (due to dopaminergic stimulation on the emetic center), diarrhea, thirst, paresthesias, confusion, rapid and weak pulse, unconsciousness, convulsions (&dquo;convulsive ergotism&dquo;), most common Acute sudden death. 3,6,7 In chronic intoxication, ischemia of the extremities is the most common form of presentation. In a review of controlled clinical trials in the use of ergotamine for and even migraine, Meyler found that more than two thirds of serious side effects attributable to ergotamine were caused by vasoconstriction.’ The remainder were caused by fibrosis (cardiac valves, anorectal ulcers, retroperitoneal or pulmonary fibrosis). As previously mentioned, the biologic effects of the EA can persist for days following adminis- tration,8°9 but the plasma levels will be detected only for a short time after dosing. This dissociation between plasma concentrations of the parent drug and the observed biologic effects of EA make the diagnosis of ergotism more difficult. The physician must therefore base the diagnosis on the history of migraine and EA intake, the clinical findings, and a high index of suspicion. In our review of the literature of reported cases of vascular insufficiency secondary to ergotism, a pattern of EA use could be identified. Most patients were chronic users of EA for migraine therapy who increased the intake of these drugs due to worsening of migraine attacks before developing classical symptoms of vascular insufficiency. It is likely that most of these patients had subclinical ergotism that became symptomatic when they increased EA intake, exacerbating the vasospasm. Diagnosis high index of suspicion and a history of possible chronic use (and possible abuse) of EA are necessary to make the diagnosis. Physical findings compatible with arterial ischemia in a young patient with history of migraines and no risk factors for atherosclerosis should raise the possibility of ergotism. The differential diagnosis of ischemic limbs includes atherosclerosis, vasculitis, Buerger’s disease, thromboembolic events, aneurysms, and drug-induced vasospasm (Table I). Pulse volume recording (PVR) and anklebrachial index (ABI) are helpful tests that may help confirm the diagnosis of ischemia, but will not help to identify the cause. In contrast, duplex ultrasound and plethysmography are noninvasive imaging tests that can be used to help identify the causes of ischemia. The lack of atherosclerotic plaques in a patient with ultrasonographic evidence of occlusive disease increases the suspicion for vasospasm due A Downloaded from ang.sagepub.com at UNIV OF MONTANA on April 9, 2015 354 to vasculitis or ergotism. These two conditions be differentiated with results of specific labo- can ratory tests. Arteriography, the gold standard test for the diagnosis of vasospasm, can be therapeutic in patients with EA-induced ischemia. If relief of va- sospasm is obtained with the use of intraarterial vasodilators in a patient with antecedent EA intake, the diagnosis of ergotism-induced ischemia is corroborated. Three angiographic findings can be present: (1) arterial spasm, usually bilateral and symmetric with abrupt or smooth areas of narrowing; (2) collateral vessels, which may disappear following withdrawal of the medication; and (3) thrombi formation, the latter being rarely reported. 18 In one unusual case, the angiogram showed Table I. Differential ischemic limbs. diagnosis of pseudoaneurysms. 27 Why collateral vessels do not prevent vasospasm is unknown, but as suggested by Enge et al, this can be due to a difference between the composition of the muscular layers of the vessels.l6 It has been proposed that vessel sensitivity to EA may predispose some patients to ergotism.28 Similar factors may also explain why vasospasm develops in different arteries in different patients. Subclinical Ergotism The vasospasm induced by EA may, in the early stages of this condition, be largely asymptomatic. In some cases, the patients had symptoms of vascular insufficiency for years before the diagnosis was made. 4,16 Bongard et al reported four patients with ergotamine-induced vasospasm who had moderate symptoms for weeks before the onset of acute ischemia .30 Diege-Petersen et al reported subclinical ergotism (ergotamine-induced physiologic vascular changes without clinical symptoms) in 30 patients taking ergotamine daily for more than 1 year. When ankle blood pressures were measured with strain-gauge plethysmography, all patients had abnormal low foot systolic blood pressures or values in the lower range of normal. 31 Other authors have reported the effect of ergotamine in the vascular system. 21,27,32 The toearm systolic blood pressure gradients were decreased at 24 hours in 10 patients receiving ergotamine suppositories within therapeutic doses. ergotamine produced coronary vapatients with recurrent angina pectoris at rest. Four of these patients had ECG changes compatible with myocardial ischemia. Acute myocardial infarction secondary to the use of ergotamine, probably caused by severe Intravenous sospasm in nine of 10 coronary vasospasm, has been reported,22 and exacerbation of angina in patients with coronary 6 artery disease is not uncommon.6 Several risk factors for ergotamine intoxication have been reported, including sepsis, febrile Downloaded from ang.sagepub.com at UNIV OF MONTANA on April 9, 2015 355 malnutrition, avitaminosis, coronary heart disease, hepatic disease, renal insufficiency, thyrotoxicosis, hypertension, pregnancy, peripheral vascular disease, and smoking. 4,18 states, Therapy The first therapeutic measure is discontinuation of the EA; however, the vasospasm may be prolonged for up to a week following withdrawal of these agents .30 The use of heparin and antiplatelet agents is also recommended as prophylaxis to prevent secondary thrombosis related to stasis. While there are no clinical trials showing the benefits of oral or intravenous vasodilator therapy in patients with ergotamine-induced vasospasm, these medications have been used extensively to treat the ischemic complications and appear to be the most effective therapy. Vasodilator therapy should be continued for few days, since the vasospasm usually recurs.29 There are reports of some refractory cases. Since ergotamine is tightly bound to alpha receptors, the vasospasm due to these compounds may not respond to vasodilators.6Intravenous or intraarterial nitroprusside, 22,26,33 nitroglycerin,34 nifedipine,35 and prostaglandins36 have been used. The latter have been reported to be effective in refractory cases of ergotism.23 Oral medications such as captopril, prazosin, and nifedipine have been tried successfully. In our patient, we used a combination of all these medications because of the severity and duration of symptoms. Sympathetic blockade has been attempted when vasodilator therapy has failed, but the efficacy is controversial. 16 Other forms of therapy include hyperbaric oxygen, mechanical intraarterial vasodilatation, 37 and epidural spinal cord stimulation.38 The patient described in this report had signs and symptoms of chronic ischemia of both lower extremities related to the use of ergotamine. Furthermore, the carotid duplex ultrasound on admission showed significant stenosis from vasospasm correlating the clinical findings of carotid bruits, which disappeared after therapy was initiated. It is remarkable that the patient used oral ergotamine products intermittently for her migraine attacks in therapeutic doses, and that her symptoms persisted for 2 weeks after she stopped taking these medications. Conclusion Ergotamine-induced ischemia, although rare, should still be considered in the differential diagnosis of ischemic limbs, especially in younger patients with a history of headaches that present with symptoms of progressive ischemia. A history of ergotamine use should always be obtained, including dosages, frequency, and when the last time these medications were used. In most of the Latin American countries, ergotamine-containing medications can be purchased without a prescription. Finally, a high index of suspicion is required to make the diagnosis of this rare condition. Acknowledgment To Mr. Robert Cravero from the photography de- partment at Cleveland Clinic Florida for preparing the pictures and photographs for this manuscript. REFERENCES 1. Ancalmo N, Ochsner J: Peripheral ischemia secondary to ergotamine intoxication. Arch Surg 109:832- 834, 1974. 2. Teasdale D, Cuschieri R: Severe reversible arterial spasm with ergotamine. Br J Clin Pract 49:214, 1995. Paraskevopoulos J, 3. Goodman RL, Gilman JB (eds): The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, 9th ed. New York: McGrawHill, 1995, pp 491-493. Hemingway D: Ergot poisoning with multisystem involvement. Milit Med 10:257-260, 1965. 5. Silberstein S: The Pharmacology of ergotamine and dihydroergotamine. Headache 37(suppl1):S15-S25, 1997. 4. 6. Merhoff G, Porter J: Ergot intoxication: Historical review and description of unusual clinical manifestations. Ann Surg 180:773, 1974. 7. Meyler W: Side effects of ergotamine: Cephalalgia 16:5-10, 1996. Review. 8. Muller-Schweinitzer E, Rosenthaler J: Dihydro-ergotamine : Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and mechanism of venoconstrictor action in beagle dogs. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 9:686-693, 1987. 9. Ibraheem J, Paalzow L,Tfelt-Hansen P: Kinetics of ergotamine after intravenous and intramuscular administration to migraine sufferers. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 23:235-240, 1982. Downloaded from ang.sagepub.com at UNIV OF MONTANA on April 9, 2015 356 10. Tfelt-Hansen P: The effect of ergotamine on the arterial system in man. Acta Pharmacol Toxicol (Copenh) 59(suppl 3) :1-30, 1986. 30. 11. Muller-Schweinitzer E: In vitro studies on the duration of action of dihydroergotamine. Int J Clin Pharmacol 18:88-91, 1980. Faberger S, Jorulf H, Sanderg C: Ergotism, arteriospastic disease and recovery, studied angiographically. Acta Med Scand 182:769-772, 1967. 13. Fukui S, Coggia M, Goeau-Brissonniere O: Acute upper extremity ischemia during concomitant use of ergotamine tartrate and ampicillin. Ann Vasc Surg 12. 14. 11:420-424, 1997. Hayton A: Precipitation of acetyloendomycin. 29. 31. Curry R, Yalamanchili R: Recurrent ergotism: A case report. J Fam Pract 6:769-773, 1978. Bongard O, Bounameaux H: Severe iatrogenic ergotism : Incidence and clinical importance. VASA 20:153-156, 1991. Diege-Petersen H, Lassen N, Tonnensen K, et al: Subclinical ergotism. Lancet 2:65-66, 1977. 32. Tfelt-Hansen P, Eickhoff J, Olesen J: The effect of single dose ergotamine tartrate on peripheral arteries in migraine patients: Methodological aspects and time effect curve. Acta Pharmacol Toxicol 47:151-156, 1980. 33. Wells K, Steed D, ergotism by 69:42-50, 1969. acute NZ Med J tri- C, Joubert P, Buys A: Severe peripheral ischemia during concomitant use of beta-blockers and ergot alkaloids. Br Med J 289:288-289, 1984. 15. Venter Zajko A, et al: Recognition and of arterial insufficiency from cafergot. J Vasc Surg 4:8-15, 1986. 34. Hussun B, Metz P, Rasmusen J: Nitroglycerin infusion for ergotism. Lancet 2:794-795, 1979. treatment Enge I, Sivertssen E: to therapeutic doses of ergotamine 1965. tartrate. Am Heart J 70:665-670, 35. Kermerer V, Daghen F, Pais S: Successful treatment of ergotism with nifedipine. Am J Roentgenol 143:333-334, 1984. M, Gimenez A, Sieyro F, et al: Intoxicacion ergotaminica. Dos casos de ischemia periferica. Angiologia (Spain) 4:148-152, 1991. 18. Bagby R, Cooper R: Angiography in ergotism. Report Piquemal R, Emmerich J, Guilmot J, et al: Successful treatment of ergotism with iloprost: A case report. Angiology 49:493-497, 1998. 37. Shifrin E, Olschwang D, Perel A, et al: Reversal of ergotamine-induced arteriospasm by mechanical in- 16. Ergotism due 36. 17. Cairols of and review of the literature. Am J Radium Ther Nucl Med 116:179-186, traarterial dilatation. Lancet 13:1278-1279, 1980. two cases Roentgenol 1972. 19. Pader E: Leriche syndrome in a patient with prolonged and continuous use of ergot derivatives. Vasc Dis 4:380-388, 1967. 38. Lepantalo M, Rosenberg P, Pohjola J, et al: Epidural spinal cord stimulation in the treatment of limb threatening vasospasm—report of a case with a fiveyear follow-up. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 11:368370, 1996. Phillips M, Vacek J: St. Anthony’s Fire: A medieval disease in modern times: Case history. Angiology 40:929-932, 1989. 20. Weaver R, 21. Montz R, Hanrath P, et al: Non-invasive method for recognition of coronary artery spasm: 201 thallium sequential scintigraphy of the myocardium after ergotamine provocation. Dtsch Wochenschr 105:509-515, 1980. Mathey D, 22. Goldfisher J: Acute myocardial infarction secondary to ergot therapy. New Engl J Med 262:860, 1960. 23. Fedotin M, Hartman C: Ergotamine poisoning prorenal arterial spasm. New ducing 283:518-520, 1970. 24. Greene F, Ariyan S, Stansel ripheral Surgery 25. Ritcher tion of 1973. vascular ischemia 81:176-179, 1977. Engl J Med H: Mesenteric and pe- secondary to ergotism. A, Banker V: Carotid ergotism. A complicamigraine therapy. Radiology 106:339-340, 26. Lazarides M, Karageorgiou C, Tsiara S, et al: Severe by ergotism. J Cardiovasc Surg facial ischemia caused 33:383-385, 1992. 27. Tarnower A, Alguire P: Ergotism masquerading as teritis. Postgrad Med J 85:103-108, 1989. ar- 28. Tfelt-Hansen P, Olesen J. Arterial response to ergotamine tartrate in abusing and nonabusing migraine patients. Acta Pharmacol Toxicol 48:69-72, 1981. Downloaded from ang.sagepub.com at UNIV OF MONTANA on April 9, 2015