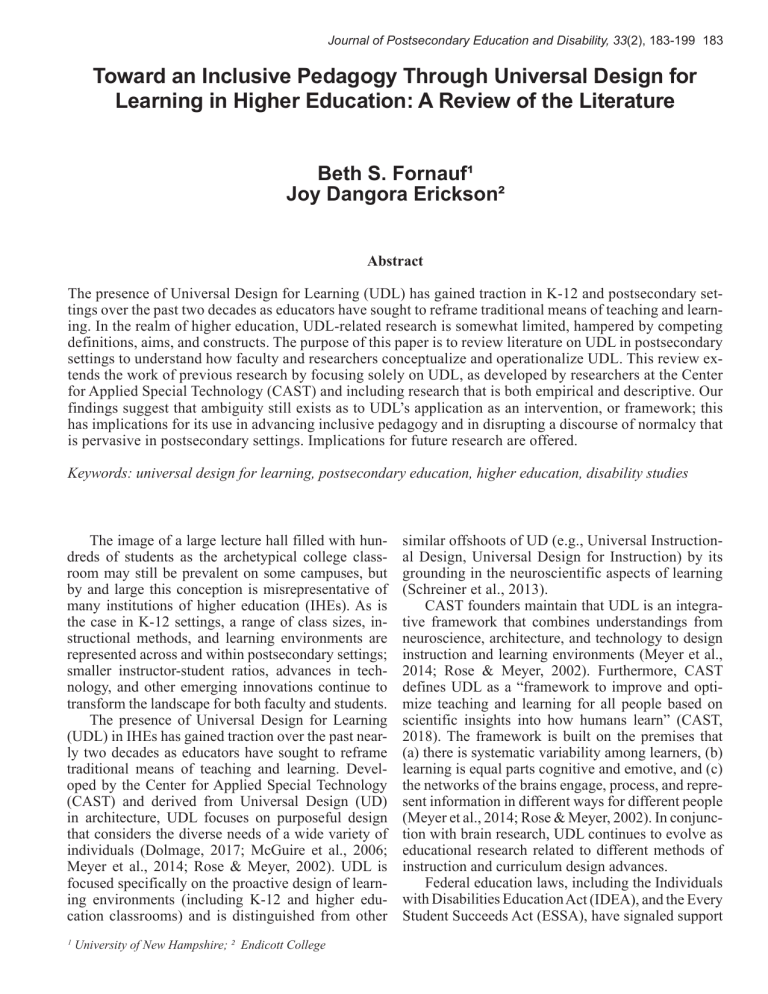

Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 33(2), 183-199 183 Toward an Inclusive Pedagogy Through Universal Design for Learning in Higher Education: A Review of the Literature Beth S. Fornauf, University of New Hampshire, Joy Dangora Erickson, Endicott College Beth S. Fornauf¹ Joy Dangora Erickson² Abstract The of Universal Design Design for Learning has gained traction K-12 and postsecondary settings over the past two setThepresence presence of Universal for (UDL) Learning (UDL) has ingained traction in K-12 and postsecondary decades as educators to reframe traditional means of teaching and learning. In the realm of higher education, tings over the pasthave two sought decades as educators have sought to reframe traditional means of teaching and learnUDL-related is somewhat limited, hampered by competing definitions, aims, and constructs. purpose of paper is to ing. In theresearch realm of higher education, UDL-related research is somewhat limited, The hampered bythis competing review literature on UDL in postsecondary settings to understand how faculty and researchers conceptualize and operationalize definitions, aims, and constructs. The purpose of this paper is to review literature on UDL in postsecondary UDL. This review ex- tends the work of previous by focusing solely on UDL, developed by researchers at the Centerexfor settings to understand how faculty and research researchers conceptualize andasoperationalize UDL. This review Applied Special Technology (CAST) and including research that is both empirical and descriptive. Our findings suggest that tends the work of previous research by focusing solely on UDL, as developed by researchers at the Center ambiguity still exists as toTechnology UDL’s application as an intervention, or framework; hasisimplications for its use in advancing inclusive for Applied Special (CAST) and including researchthisthat both empirical and descriptive. Our pedagogy and in disrupting a discourse of normalcy that is pervasive in postsecondary settings. Implications for future research are findings suggest that ambiguity still exists as to UDL’s application as an intervention, or framework; this offered. has implications for its use in advancing inclusive pedagogy and in disrupting a discourse of normalcy that is pervasive in postsecondary settings. Implications for future research are offered. Keywords: universal design for learning, postsecondary education, higher education, disability studies The image of a large halllecture filled with hundreds students The image oflecture a large hall filled of with hunas the archetypical college may still be prevalent on dreds of students as classroom the archetypical college classsome campuses, but by and large this conception is room may still be prevalent on some campuses, but misrepresentative of many institutionsisofmisrepresentative higher education (IHEs). by and large this conception of As is the case in K-12 settings, a range of class sizes, many institutions of higher education (IHEs). As is instructional methods, and learning environments are the case in K-12 settings, a range of class sizes, inrepresented across and within postsecondary settings; smaller structional methods, and learning environments are instructor-student ratios, advances in technology, and other represented across and within postsecondary settings; emerging innovations continue to transform the landscape for smaller instructor-student ratios, advances in techboth faculty and students. The presence of Universal Design for nology, and other emerging innovations continue to Learning (UDL) in IHEs has gained traction over the past nearly transform the landscape for both faculty and students. two decades as educators have sought to reframe traditional The presence of Universal Design for Learning means of teaching and learning. Developed by the Center for (UDL) in IHEs has gained traction over the past nearApplied Special Technology (CAST) and derived from Universal ly two decades as educators have sought to reframe Design (UD) in architecture, UDL focuses on purposeful design traditional means of teaching and learning. Develthat considers the diverse needs of a wide variety of individuals oped by 2017; the Center Applied Special (Dolmage, McGuirefor et al., 2006; Meyer et al.,Technology 2014; Rose (CAST) and derived from Universal Design (UD) & Meyer, 2002). UDL is focused specifically on the proactive in architecture, UDL focuses on purposeful design design of learning environments (including K-12 and higher that considers the and diverse needs of from a wide education classrooms) is distinguished othervariety of individuals (Dolmage, 2017; McGuire et al., 2006; Meyer et al., 2014; Rose & Meyer, 2002). UDL is focused specifically on the proactive design of learning environments (including K-12 and higher education classrooms) and is distinguished from other 1 University of New Hampshire; 2 Endicott College similar offshoots of UDof (e.g., InstructionalInstructionDesign, similar offshoots UDUniversal (e.g., Universal Universal Design for Instruction) by itsfor grounding in the by its al Design, Universal Design Instruction) neuroscientific aspects of learning (Schreiner et al., of 2013). CAST grounding in the neuroscientific aspects learning founders maintain that UDL is an integrative framework that (Schreiner et al., 2013). combines understandings from neuroscience, architecture, and CAST founders maintain that UDL is an integratechnology to design instruction and learning environments tive framework that combines understandings from (Meyer et al., 2014; Rose & Meyer, 2002). Furthermore, CAST neuroscience, architecture, and technology to design defines UDL as a “framework to improve and optimize teaching instruction and learning environments (Meyer et al., and learning for all people based on scientific insights into how 2014; Rose & Meyer, 2002). Furthermore, CAST humans learn” (CAST, 2018). The framework is built on the defines UDL as a “framework to improve and optipremises that (a) there is systematic variability among learners, mize teaching and learning for all people based on (b) learning is equal parts cognitive and emotive, and (c) the scientific insights into how humans learn” (CAST, networks of the brains engage, process, and represent 2018). The framework is built on the premises that information in different ways for different people (Meyer et al., (a) there is systematic variability among learners, (b) 2014; Rose & Meyer, 2002). In conjunction with brain research, learning is equal parts cognitive and emotive, and (c) UDL continues to evolve as educational research related to the networks brainsand engage, process, repredifferent methodsof of the instruction curriculum designand advances. sent information in different ways for different people Federal education laws, including the Individuals with Disabilities (Meyer et 2014;and Rose & Meyer, 2002). In conjuncEducation Actal., (IDEA), the Every Student Succeeds Act tion with research, (ESSA), havebrain signaled support UDL continues to evolve as educational research related to different methods of instruction and curriculum design advances. Federal education laws, including the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), and the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), have signaled support 184 Fornauf & Erickson; Inclusive Pedagogy (McGuire et al., 2006). A primary the review by for in elementary and secondary schools. The 1997 ary settings (McGuire et al., 2006).reason A primary reason forUDL UDL in elementary and secondary schools. The settings and colleagues is centered on UDI rather on UDLon reauthorization of IDEA pushed the boundaries of educational the review by Roberts and colleagues is than centered 1997 reauthorization of IDEA pushed the boundaries Roberts may very well be that the use of UDL outside of K-12 settings access, requiring that students with labeled disabilities be of educational access, requiring that students with la- UDI rather than on UDL may very well be that the at that Recently however, appears educated in the least restrictive environment the greatest useespecially of UDLlimited outside oftime. K-12 settings was itespecialbeled disabilities be educated in thetoleast restrictive was that UDL has been more widely accepted as a relevant extent possible, and provided with assistive technology. This law environment to the greatest extent possible, and pro- ly limited at that time. Recently however, it appears designing experiences represented (theoreticaltechnology. if not practical) union between special framework that UDLforhas been postsecondary more widelylearning accepted as a relevided witha assistive This law represented and/or environments (UDL on Campus, n.d.). As such, UDL has and general education (Hehir, 2009). According to CAST a (theoretical if not practical) union between special vant framework for designing postsecondary learning become a more familiar term across educational age spans researchers, IDEA effectively opened the door for a UDL experiences and/or environments (UDL on Campus, and general education (Hehir, 2009). According to also with a multitude of theoretical and practical interpretations. approach in K-12 classrooms; however, UDL has undergone CAST researchers, IDEA effectively opened the door n.d.). As such, UDL has also become a more familiar much theoretical revision since that time (Meyer et al., 2014). An Nevertheless, Roberts and colleagues’ 2011 re- view detailed for a UDL approach in K-12 classrooms; however, term across educational age spans with a multitude of several noteworthy findings. First, the authors found very little unintended consequence of linking UDL with policies related to UDL has undergone much theoretical revision since theoretical and practical interpretations. research that explored the effectiveness of UD models on student students with labeled disabilities is the conflation of UDL and that time (Meyer et al., 2014). Nevertheless, Roberts and colleagues’ 2011 reoutcomes (GPA, retention rates, etc.). In addition, these authors special education. UDL is often misinterpreted as a special An unintended consequence of linking UDL view detailed several noteworthy findings. First, the education initiative, or a framework only for students with labeled emphasized that empirical work exploring UD in higher education with policies related to students with labeled disabilauthors found very little research that explored the efwould benefit from more quantitative and mixed methods disabilities. The 2015 passage of ESSA may have somewhat ities is the conflation of UDL and special education. approaches. fectivenessThe of authors UD models on student outcomes (GPA, expressed concern that three-fourths of assuaged this confusion—for the first time, UDL as a practice UDL is often misinterpreted as a special education retention rates, etc.). In addition, thesemethods, authorswhich emthe pieces in their re- view employed qualitative was endorsed by federal general education legislation (Gravel, initiative, or a framework only for students with laphasized that empirical work exploring UD in higher 2017). While UDL’s founding organization, CAST, has historical substantially limited the generalizability of their findings. Since the beled disabilities. 2015 UDL passage ofonESSA educationof would fromthere more quantitative Roberts benefit et al.’s review have been four and connections with specialThe education, focuses learnermay publication have somewhat this confusion—for the subsequent mixed methods approaches. The authors expressed reviews of UDL-related literature. While some of variability rather than assuaged disability. Furthermore, the UDL framework first time, UDL as a practice was endorsed by fedconcern that three-fourths of the pieces in their rethese have incorporated UDL applications in higher education, can be applied to settings outside the confines of K-12 education, eral general education legislation (Gravel, 2017). view employed qualitative methods, which substannone have concentrated solely on postsecondary settings. as evidenced by its definition in the 2008 reauthorization of the WhileEducation UDL’sOpportunity foundingAct. organization, CAST, tially limited thevaried generalizability of their these have in focus, examining UDLfindings. in PK-12 Higher This extension of UDL intohas Rather, historical connections withinspecial education, Since the of Roberts etoral.’s (Ok publication et al., 2017), Universal Design UDL review as an higher education will be explored this paper. Despite theUDL environments focuses on learner variability ratherinitiatives, than disability. there haveintervention been four(Capp, subsequent reviews of UDL-reeducational 2017; Rao et al., 2014), and UDL prevalence of UDL in statewide educational federal Furthermore, thepreservice UDL framework can becoursework applied to aslated literature.framework While some of these have Each incorpoan educational (Al-Azawei et al., 2016). of legislation, and even teacher education settings the confines ofperiences K-12 education, as these ratedreviews UDLmakes applications in highertoeducation, a distinct contribution the literature.none (Scott et al.,outside 2017), research on the exof UDL by both and Capp (2017), Rao and col- leagues implementation educators at multiple is limited (Gravel, Analyses evidenced bybyits definition in thelevels 2008 reauthorizahave concentrated solely on and postsecondary settings. highlight outcomes of UDL as an intervention; 2017). In the of higher education, UDL-related Act. research is (2014) tion of therealm Higher Education Opportunity Rather, thesethehave varied in focus, examiningboth UDL the generally positive effects UDL at not only limited, but ambiguous—hampered by competing This extension of UDL into higher education note in PK-12 environments (Okof et al.,implementation 2017), Universal educational Capp’s meta-analysis is theoretically definitions and interpretations. While guidelines for prevalence various will be explored in this paper. Despite the Design or UDL levels. as an educational intervention (Capp, situated within an inclusive education framework and examines implementation exist (CAST, 2018), many UDL scholars are of UDL in statewide educational initiatives, federal 2017; Rao et al., 2014), and UDL as an educational the outcomes of(Al-Azawei UDL implementation empirical studies reluctant to identify definitions or criteria. UDL iseducation intended legislation, andstrict even preservice teacher framework et al., in2016). Each of these between 2013 and 2016 (N=18). Rao et al. captured somewhat neither as a program, nor as something to implement with fidelity. coursework (Scott et al., 2017), research on the ex- reviews makes a distinct contribution to the aliterature. sense the terrain of Universal Design, the Thus, there are of UDL; a sense, its at broader periences ofmultiple UDL interpretations Analyses byofboth and Capp (2017), and examining Rao and colimplementation byin educators efficacy of multiple models of UD (e.g., Universal Design for dynamic and flexible nature can also be interpreted as its multiple levels is limited (Gravel, 2017). In the realm leagues (2014) highlight the outcomes of UDL as an Universal Design, UDL) across primary, greatest source of elusiveness. Despite this ambiguity, intervention; bothInstructional note the generally positive effects of higher education, UDL-related researchUDL is has not Instruction, secondary, and higher educational settings. The authors included had successful forays into higher education, both in research and levels. only limited, but ambiguous—hampered by compet- of UDL implementation at various educational empirical research in their (N=14), with the goalwithof in practice. A 2011 literature review synthesized empirical work in only meta-analysis is review theoretically situated ing definitions and interpretations. While guidelines Capp’s understanding how researchers are employing different models postsecondary education related to UDL; however, included for implementation exist (CAST, 2018), many UDL in an inclusive education framework and examines UD as an intervention. Al-Azawei and colleagues’ (2016) publications drew on other UD models as well (Roberts et al., outcomes of UDL implementation in empirical scholars are reluctant to identify strict definitions or ofthe aimed to pick up where Rao et al. (2014) left off; however, 2011). Universal De- sign for Instruction (UDI) was once criteria. UDL is intended neither as a program, nor review studies between 2013 and 2016 (N=18). Rao et al. they analyzed only those empirical studies that utilized the UDL considered the version of UD most applicable to higher as something to implement with fidelity. Thus, there captured a somewhat broader sense of the terrain of framework (CAST, 2018; Rose & education, as it was specifically developed for use in are multiple interpretations of UDL; in a sense, its Universal Design, examining the efficacy of multiple postsecondary dynamic and flexible nature can also be interpreted as its greatest source of elusiveness. Despite this ambiguity, UDL has had successful forays into higher education, both in research and in practice. A 2011 literature review synthesized empirical work in postsecondary education related to UDL; however, included publications drew on other UD models as well (Roberts et al., 2011). Universal Design for Instruction (UDI) was once considered the version of UD most applicable to higher education, as it was specifically developed for use in postsecond- models of UD (e.g., Universal Design for Instruction, Universal Instructional Design, UDL) across primary, secondary, and higher educational settings. The authors included only empirical research in their review (N=14), with the goal of understanding how researchers are employing different models of UD as an intervention. Al-Azawei and colleagues’ (2016) review aimed to pick up where Rao et al. (2014) left off; however, they analyzed only those empirical studies that utilized the UDL framework (CAST, 2018; Rose & Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 33(2) 185 Meyer, The The authors of this review while the consciously shifted their interpretations of disabilityof away from consciously shifted their interpretations disability Meyer,2002). 2002). authors of thisconcluded review that concluded literature suggested that UDL holds promise as a pedagogical deficits to disablingdeficits environments (Gravel, Edwards, away from individual to disabling environthat while the literature suggested that UDL holds individual framework grade spans andframework formats (online, hybrid,grade etc.), Buttimer, & Rose, 2015; Meyer etButtimer, al., 2014), which is somewhat ments (Gravel, Edwards, & Rose, 2015; promise across as a pedagogical across the ways in which researchers interpret and comply with UDL consistent with a DSE framework. DSE supports the notion that spans and formats (online, hybrid, etc.), the ways in Meyer et al., 2014), which is somewhat consistent principles remain ambiguous. No clear about the validity with framework. certain types ofDSE bodily (cognitive, behavioral, with a DSE supports the notion that which researchers interpret andanswers comply with UDL individuals of UDL as a framework were realized. This review is distinctly linguistic, etc.) impairments are disabled by inhospitable principles remain ambiguous. No clear answers about individuals with certain types of bodily (cognitive, different from prior re- views for several reasons. While our aim is environments and social systems that privilege able bodies, often behavioral, linguistic, etc.) impairments are disabled the validity of UDL as a framework were realized. to gain a sense of the scope of Universal Design research in in discrimination or exclusion (Gabel, 2005). Likewise in by inhospitable environments and social systems that This review is distinctly different from prior re- resulting higher education like Roberts and colleagues (2011), we have K-12 settings, the expectation is that students with disabilities views for several reasons. While our aim is to gain privilege able bodies, often resulting in discriminaelected to look beyond empirical work that emphasizes outcomes should somehow be normalized; the teacher’s role is to a sense of the scope of Universal Design research in tion or exclusion (Gabel, 2005). Likewise in K-12 and seeks validity. We are interested in the application of UDL remediate students with individual education programs (IEPs) in higher education like Roberts and colleagues (2011), settings, the expectation is that students with disabilthat advances and sustains inclusive pedagogy as an end in order to make them more like their “typical” peers. Ironically, this we have elected to look beyond empirical work that ities should somehow be normalized; the teacher’s itself. By analyzing empirical and descriptive pieces, we hope to often happens by removing these students from the classroom emphasizes outcomes and seeks validity. We are in- role is to remediate students with individual educagain a clearer understanding of the various ways researchers in and attempting to raise them to a “normally” performing level terested in the application of UDL that advances and tion programs (IEPs) in order to make them more like higher education are operationalizing and conceptualizing UDL. before readmitting them in the general class- room (Hehir, 2002; sustains inclusive pedagogy as an end in itself. By their “typical” peers. Ironically, this often happens Due to its continued iteration and development in the years since Taylor, 1988). The UDL framework can disrupt the narrative of analyzing and todescriptive we hope achieving by removing these the (Taylor, classroom its inception, empirical we have elected focus solely pieces, on the UDL readiness as astudents gateway tofrom inclusion 1988),and as to gain a clearer understanding of the various ways attempting to raise them to a “normally” performing framework (CAST, 2018; Meyer et al., 2014; Rose & Meyer, it recognizes learner variability as an educational norm, and researchers in higher education operationalizlevel the before themasinthethe general class2002) to the exclusion of other UD models.are Additionally, because rejects “myth readmitting of the normal child” central, organizing ing specifically and conceptualizing UDL. Due to educational its continued feature room of (Hehir, Taylor, 1988). UDL has been ad- dressed in higher schools2002; (Baglieri, Bejoian et al., 2011, p. 2124). Yet iteration and development in the years since its inThe UDL framework can disrupt theUDL narrative policy and practice, it has demonstrated its sustainability in an due to its complicated history and development, continuesof ception, we have elected to focus solely on the UDL achieving readiness as a gateway to inclusion educational climate that is constantly in flux. The questions to be positioned in research, as this paper will illustrate,(Taylor, as a framework (CAST, 2018; Meyer et al., 2014; Rose & 1988),for asdealing it recognizes learner variability as anofeduguiding this review are as follows: solution with disability or difference. A number Meyer, 2002) to the exclusion of other UD models. descriptive cational and norm, and rejects the included “myth inofthis thereview normal empirical publications Additionally, because UDL specifically has been ad- begin child” as thetheir central, of schools by framing piecesorganizing as a responsefeature to increased diversity dressed in higher educational policy and practice, it in(Baglieri, Bejoian et al., 2011, 2124). Yet due to IHEs, which, while admirable, runs thep.risk of positioning has demonstrated its sustainability in an educational non-dominant its complicated history and development, UDL con(non-white, disabled, etc.) groups of students as homogeneous, and (2) deviants in need of climate that is constantly in flux. The questions guid- (1) tinues to be positioned in research, asassimilating this papertowill heteronormative typicality higher ing this review are as follows: illustrate, as astandards solutionthat fordefine dealing within disability or education. ThisA paper critically the suitability of framing difference. number ofquestions descriptive and empirical as an intervention for improving out- comes for certain 1. In what ways is the UDL framework opera- UDL publications included in this review begin by framgroups of students in the increasingly diverse realm of ing their pieces as a response to increased diversity tionalized in postsecondary contexts? education. we argue thatthe UDL is aof poin IHEs, which, whileInstead, admirable, runs risk 2. In what ways is UDL conceptualized as a postsecondary process-based framework for inclusive pedagogy that moves etc.) framework for inclusive pedagogy in higher sitioning non-dominant (non-white, disabled, compensatory measures support groupsassimilationist of students and as (1) homogeneous, andof(2) devieducation, attending to notions of disability, “beyond view to advancing inclusive forms of pedagogy to meet antsa in need of assimilating to heteronormative stanability, and variability in theory and practice? with learner diversity in non-discriminatory and socially just ways” dards that define typicality in higher education. (Liasidou, p.127). In otherquestions words, rather This2014, paper critically thethan suitability of Conceptual Framework conceptualizing inclusion in higher education accommodating framing UDL as an intervention for asimproving outstudents with disabilities, UDL as inclusive pedagogy takes up The conceptual framework for this review attends to the ways UDL functions The conceptual framework for this review attends comes for certain groups of students in the increasto support inclusive pedagogy in higher education. Yet the concept of task of transforming teaching and learning at the to the ways UDL functions to support inclusive ped- the ingly diverse realm of postsecondary education. inclusivity always brings with it a myriad of complexities of placement, postsecondary level for all students. This is a task made more agogy in Yet the concept incluInstead, we argue that UDL is a process-based framebelonging, andhigher the rights education. of individuals with disabilities. As alludedof to in the complex by the fact that many faculty are content experts with introduction, UDL hasbrings deep connections special education, and is sivity always with it with a myriad of complexities work for inclusive pedagogy that moves “beyond aslimited pedagogical experience, other than their own as a student sometimes viewed as a special education initiative. Yet theoretically, UDL of placement, belonging, and the rights of individuals similationist and compensatory measures of support appears to be more closely aligned with Disability Studies in Education (DSE). (McGuire with disabilities. As alluded to in the introduction, UDL has deep connections with special education, and is sometimes viewed as a special education initiative. Yet theoretically, UDL appears to be more closely aligned with Disability Studies in Education (DSE). DSE is concerned with problems and issues in education related to exclusion and/or oppression of individuals with disabilities. DSE conceptualizes disability as a social, political, and cultural construct that plays out in complex ways in educational settings (Cosier & Ashby, 2016). UDL scholars have DSE is concerned with problems and issues in education related to exclusion and/or oppression of individuals with disabilities. DSE conceptualizes disability as a social, political, and cultural construct that plays out in complex ways in educational set- tings (Cosier & Ashby, 2016). UDL scholars have with a view to advancing inclusive forms of pedagogy to meet learner diversity in non-discriminatory and socially just ways” (Liasidou, 2014, p.127). In other words, rather than conceptualizing inclusion in higher education as accommodating students with disabilities, UDL as inclusive pedagogy takes up the task of transforming teaching and learning at the postsecondary level for all students. This is a task made more complex by the fact that many faculty are content experts with limited pedagogical experience, other than their own as a student (McGuire 186 Fornauf & Erickson; Inclusive Pedagogy et al., 2006). Thus, a further goal of this paper is to propose avenues for future research. This will be explored further in the discussion. context; pieces that incorporated UDL as content within a course (for example, teaching pre-service teachers about UDL) were excluded (e.g., Pearson, 2015). Methods Criteria for Locating and Selecting Publications In order locate to high-quality publications, wepublications, conducted a we In toorder locate high-quality search of the Education In- formationResources Center (ERIC) conducted a searchResources of the Education Indatabase using the following key database terms: “Universal for formation Center (ERIC) using Design the followLearning” “UDL,” combined with Design either “higher ing keyorterms: “Universal for education” Learning”or or “postsecondary education.” This initial search yielded 247 “UDL,” combined with either “higher education” or articles. The abstracts of these articles were read and applied the “postsecondary education.” This initial search yieldfollowing for inclusion in this review: ed 247criteria articles. The abstracts of these articles were read and applied the following criteria for inclusion in this review: Analysis The resultant set of 38set publications spanned the years 2006 to The resultant of 38 publications spanned the 2018 included empirical studies and descriptive yearsand2006 to 2018 andresearch included empirical research articles. the articles, eachAfter one was loggedthe intoartia studiesAfter andreading descriptive articles. reading spreadsheet in which recorded theaabstract, purpose, cles, each one waswelogged into spreadsheet in which research questions, methods, data sources, and findings. The we recorded the abstract, purpose, research questions, first author coded each article to identify those that dealt with methods, data sources, and findings. The first author operationalizing UDL, and that explored its coded each article tothose identify those that dealt with conceptualization. Upon reviewing first author’s provided its operationalizing UDL, and the those that explored definitions specific to theUpon operationalization conceptualization. reviewing and theconceptualization first author’s of UDL, the second author also coded each article. The authors provided definitions specific to the operationalization were in agreement on 82% of the articles, and discrepancies and conceptualization of UDL, the second author also were resolved together; several articles could be interpreted as coded each article. The authors were in agreement on involving both the operationalization and conceptualization of 82% of the articles, and discrepancies were resolved UDL (e.g., Black et al., 2014; Hutson & Downs, 2015). In these together; several articles could be interpreted as incases, the authors revisited the publication’s stated purpose and volving both the operationalization and conceptualwhen explicitly identified by the authors, the research questions. ization of UDL (e.g., Black et al., 2014; Hutson & Definitions of operationalize and conceptualize were consulted to Downs, 2015). In these cases, the authors revisited determine which category most clearly aligned with the article’s the publication’s stated purpose and when explicitstated purposes. A list of articles in this review, organized by ly identified by the authors, the research questions. category, is provided in Table 1. Definitions of operationalize and conceptualize were consulted to determine which category most clearly aligned with the article’s stated purposes. A list of articles in this review, organized by category, is provided in Table 1. 1. Articles must be published in a peer reviewed journal. 2. Articles must be published between 2002 and 2018. The 2002 date reflects the publication of Teaching Every Student in the Digital Age: Universal Design for Learning (Rose & Meyer, 2002), which introduced principles of UDL. 3. Publications must explicitly address our research questions; thus, they need to explore how UDL is operationalized and/or conceptualized in a postsecondary setting. a. Operationalize refers to publications that explore the process of drawing on and imFindings plementing UDL in some aspect of pedagogy, coursework, or operations (e.g., all of the in this review by Almost all publications of the publications in began this review Disability Services Office). Publications Almost began by addressing UDL in relationstudent to increasing in this group asked questions about the addressing UDL in relation to increasing student diversity, broadly defined, in higherWhile educaprocess and/or outcomes of designing a diversity, broadly defined, in higher education. tion. pieces While explicitly many pieces explicitly linked UDL course, system, or learning task within the many linked UDL to the teaching and to the teaching and learning of students with disabilcontext of the UDL framework. learning of students with disabilities, others framed UDL b. Conceptualize refers to publications that ities, others framed UDL as a way to address the a way the needs ofofa students, diverse population needs oftoa address diverse population including draw on UDL theory to consider ways to as of students, including variability in age, and backgrounds, improve teaching and learning in higher variability in age, social and culturalsocial backgrounds, and learning preferences. We will and learning preferences. We will review findings education. These pieces explored ques- cultural this section, onhas howbeen in thisfindings section,infocusing firstfocusing on howfirst UDL tions about how faculty and students review operationalized, and then on its conceptualization in consider the possibilities of UDL in a UDL has been operationalized, and then on its higher educationinsettings. postsecondary setting, including how fac- conceptualization higher education settings. ulty might take up UDL in the interest of Operationalizing UDL improving their pedagogy. the firstthe research what ways is UDLways first question: researchInquestion: Inthe what 4. Publications must focus specifically on Uni- RecallRecall operationalized in postsecondary contexts? A total of is the UDL framework operationalized in postsecversal Design for Learning. Articles that fo- framework articles contexts? in this re- view operationalizing ondary A attended total ofto 27 articles inUDL this recused on other UD models (e.g., Universal 27 principles through some type of implementation in instruction, Design for Instruction) to the exclusion of view attended to operationalizing UDL principles assessment, or design. emerged from analysis of through some UDL were not reviewed. typeTwo ofthemes implementation in instruc(a) use ofor UDL in 5. Publications must display evidence of draw- these tion,articles: assessment, design. Two themes emerged ing on UDL principles in a postsecondary from analysis of these articles: (a) use of UDL in Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 33(2) 187 response to atospecific problem, and (b) achieving philosophical response a specific problem, and (b) achieving “buy-in” from faculty, stakeholders, and studentsstakeholders, in order to move philosophical “buy-in” from faculty, forward with scaling UDL across the institution. recentscaling study of and students in order to move forwardA with UDL implementation across six IHEs in the US (Moore et al., UDL across the institution. 2018)Aprovides a model that can be used as a heuristic for recent study of UDL implementation across six understanding in this subgroup the literature. IHEs in the the USthemes (Moore et al., 2018)ofprovides a model Moore and colleagues aimed to identify similarities and that can be used as a heuristic for understanding the differences in implementation strategies, and to use this themes in this subgroup of the literature. Moore and information to inform the scaling of UDL research and practice. colleagues aimed to identify similarities and differThrough interviews with faculty across selected IHEs, the authors ences in implementation strategies, and to use this found that UDL was often addressed most systematically in information to inform the scaling of UDL research response to a particular problem or line of inquiry, such as and practice. Through interviews with faculty across inequity or student attrition, which parallels theme (a) in our reselected IHEs, the authors found that UDL was often view. This targeted use of UDL to address a particular problem addressed most systematically in response to a parmay have been the result of greater “buy-in” from certain ticular problem or line of inquiry, such as inequity or administrative areas or departments concerned with that issue, student attrition,to which parallels in ourdata, rewhich corresponds theme (b). Drawingtheme on their(a) collected view. This targeted use of UDL to address a particular Moore et al. developed a four-phase model to help identify the problem mayarchave been the result of greater “buy-in” developmental of UDL implementation in higher education: fromoften certain administrative areas or departments small, individual-level implementation; traces of growthconcerned with that issue, which corresponds through the department level; securing of funding; andto theme (b). Drawing on their collected data, Moore et al.We deinstitutional implementation and adoption of UDL as policy. veloped a four-phase model to help identify the will refer to this model and examples from the review literaturedeto velopmental arc of UDL: UDLResponding implementation in higher illustrate the two themes. to Problems. Looking education: small, several often individual-level implementaacross these studies, publications did in fact frame UDL tion; tracessolution of growth through the department level; as a potential to a problem or issue in higher education. securing of funding; andininstitutional implementation In many cases, the “problem” need of attention was the success (or lack thereof) of students withWe labeled For and adoption of UDL as policy. willdisabilities. refer to this example, someexamples studies examined aspects of equity and access model and from the review literature to ilinlustrate college or coursework. In other cases, instructors theuniversity two themes. identified common challengesto within their courses or UDL: Responding Problems. Looking across departments. Moore and colleagues (2018) noted that in some these studies, several publications did in fact frame IHEs, on UDL is at a faculty level, where UDLthe asemphasis a potential solution to a problem or concerns issue in tend to reflect those of individual faculty members and a higher education. In many cases, the “problem” in commitment to studentswas and promising pedagogy. At a thereof) systems need of attention the success (or lack (university) level,with there labeled tends to be interest in addressing larger of students disabilities. For example, issues such as student attrition, racial tension, or access to some studies examined aspects of equity and access disability-related Several studies found attending to in college or services. university coursework. Inthat other cases, faculty’s instructional practices might enable access to learning instructors identified common challenges within their for a variety of diverse students, including those with disabilities, courses or departments. Moore and colleagues (2018) and facilitate inclusive classrooms (Bernacchio et al., 2007; noted that in some IHEs, the emphasis on UDL is at Gradel & Edson, 2010; Heelan et al., 2015). Similarly, one study a faculty level, where concerns tend to reflect those assessed faculty perceptions of UDL, and subsequently of individual faculty members and a commitment to designed a professional learning program aimed at creating an students and promising pedagogy. At a systems (university) level, there tends to be interest in addressing larger issues such as student attrition, racial tension, or access to disability-related services. Several studies found that attending to faculty’s instructional practices might enable access to learning for a variety of diverse students, including those with disabilities, and facilitate inclusive classrooms (Bernacchio et al., 2007; Gradel & Edson, 2010; Heelan et al., 2015). Similarly, one study assessed faculty perceptions of UDL, and subsequently designed a professional learning program aimed at creating an inclusive climate specifically geared toward inclusive climate specifically gearedstudents towardwith students disabilities (Izzo et al., 2008). studiesThese suggest that use of with disabilities (Izzo et These al., 2008). studies sugUDL principles may mitigate faculty concern about teaching gest that use of UDL principles may mitigate faculty students labeled disabilities, who may be perceived as concernwith about teaching students with labeled disabilhaving fundamentally different learning needs. True to UDL’s ities, who may be perceived as having fundamentally emphasis student learning, differentonlearning needs. several publications focused on postsecondary students’ perceptions of UDL implementation. True to UDL’s emphasis on student learning, Dean et al. (2017) zeroed in on the student outcomes of several publications focused on postsecondary stuperceived learning (e.g., whether students were positively dents’ perceptions of UDL implementation. Dean engaged) and actual learning (knowledge gains). The faculty et al. (2017) zeroed in on the student outcomes of researchers investigated the impact of using multiple forms of perceived learning (e.g., whether students were posrepresentation in a large lecture course. These resources itively engaged) and actual learning (knowledge including PowerPoint slides, lecture notes, an audience response gains). The faculty researchers investigated the imsystem, and an online learning app. Notably, the problems under pact of using multiple forms of representation in a investigation (lack of engagement and limited opportunities to large lecture course. These resources including Powlearn in large lecture) are environmental and curricular; the erPoint lecture notes, audience response authors do slides, not situate problems withinan students. In general, system, and an online learning app. Notably, research that examined student perspectives tended to focusthe problems under investigation ofmight engagement more on systemic or curricular barriers (lack that UDL address, and limited opportunities todeficits learnininlearning large ascribed lecture)to rather than attempting to overcome are environmental and curricular; the authors disability. Two studies looked at student perspectives on do not situate problems students. instruction before and within after a UDL intervention with members of In general, research examined student perthe faculty (Davies et al., 2013; that Schelly et al., 2011). Researchers spectives to focus more on systemic or cursaw a shift intended student perceptions about how their instructors ricularinformation barriers and thatattempted UDL might address, ratherthem. than shared to engage and assess attempting to overcome deficits learning ascribed These researchers attempted to measureinUDL effectiveness to disability. at student through students’Two eyes studies and offer looked an interesting glimpseperspecinto the perceived impactbefore of evenand a small amount (semester’s tives on positive instruction after a UDL intervenworth) of faculty professional on(Davies student outcomes. tion with members of thelearning faculty et al., 2013; Several in this Researchers subgroup took up theawork Schellypublications et al., 2011). saw shiftof in stuconnecting UDL with student empowerment, dent perceptions about wellness, how their instructorsand shared identity development in college classes. Nielsen (2013) examined information and attempted to engage and assess how UDLThese might be integrated into a composition course forUDL them. researchers attempted to measure first-year college students to foster positive identity development effectiveness through students’ eyes and offer an in(knowing as a learner) engagement. The author terestingoneself glimpse into theandperceived positive impact focused on highlighting UDL as aworth) useful framework of evenspecifically a small amount (semester’s of faculty for design for all students, not only those who might struggle in a professional learning on student outcomes. composition course. This piece highlights instructors can up Several publications in this how subgroup took proactively address variability in the classroom, an approach the work of connecting UDL with student wellness, consistent with the principles of UDL. In addition, student empowerment, and identity development in college empowerment was highlighted across content areas in one study classes. Nielsen (2013) examined how UDL might be exploring UDL as a means to minimize the barrier of student integrated into a composition course for first-year colstress, and foster an inclusive climate (Miller & Lang, 2016), and lege students to foster positive identity development another to increase student-centered learning and engagement (knowing oneself as a learner) and engagement. The author focused specifically on highlighting UDL as a useful framework for design for all students, not only those who might struggle in a composition course. This piece highlights how instructors can proactively address variability in the classroom, an approach consistent with the principles of UDL. In addition, student empowerment was highlighted across content areas in one study exploring UDL as a means to minimize the barrier of student stress, and foster an inclusive climate (Miller & Lang, 2016), and another to increase student-centered learning and engagement 188 Fornauf & Erickson; Inclusive Pedagogy (Kumar, 2011). Again, this is approached by proactiveby design (Kumar, 2011). Again, this is approached proacand training, not only training, in pedagogy, in identifying and tivefaculty design and faculty notbut only in pedagogy, removing barriers to learning (Meyer et al., 2014). Because UDL but in identifying and removing barriers to learning is(Meyer defined as a pedagogical framework, it is increasingly being et al., 2014). used Because in teacher education programs,asboth to prepare teachers for UDL is defined a pedagogical framediverse classrooms, and as a set of promising instructional work, it is increasingly being used in teacher educapractice (Pearson, 2015). Studies focused on the use and tion programs, both to prepare teachers for diverse introduction of UDL in teacher education also highlighted its use classrooms, and as a set of promising instructional in online or hybrid course formats. While the use of faculty practice (Pearson, 2015). Studies focused on the use modeling as a way to introduce UDL was employed in one study and introduction of UDL in teacher education also (Evans et al., 2010), the focus of these pieces tended to be on highlighted its use in online or hybrid course formats. how well preservice teachers understood UDL after not only While the use of faculty modeling as a way to introlearning about it, but participating in UDL-designed courses duce UDL was employed in one study (Evans et al., (Evmenova, 2018; Scott et al., 2015). While results indicate that 2010), the focus of these pieces tended to be on how preservice teachers were generally able to recognize and apply well preservice teachers understood UDL after not UDL principles, we must note two important points. First, only learning about it, tended but participating in special UDL-departicipants in these studies to be preservice signed courses (Evmenova, 2018; Scott et al., 2015). education teachers, highlighting again the connection between While results indicate that preservice teachers were UDL and special education. Second, we were unable to locate generally able tothe recognize UDL princistudies that explored use of UDLand with apply preservice teachers in ples, we must note two important points. First, particclinical placements, indicating a possible gap in research. ipants in these studies tended to be preservice Investigating UDL as a vehicle for improving on- line or special education teachers, highlighting again theaconnection technology-enhanced postsecondary courses was popular between UDL and special education. topic in this subgroup. While UDL neither requires Second, the use of we were unable to locate that explored the use of technology nor relies solelystudies on it to enhance pedagogy, UDL with preservice in the clinical implementation is certainly teachers facilitated by use ofplacements, electronic indicating a possible gap inaccessible research.educational media, assistive technology, and materials (Meyer et al., 2014). recent emphasize Investigating UDL asSeveral a vehicle forarticles improving onthese between UDL and technology, particularly ascourses a tool line links or technology-enhanced postsecondary for designing engaging courses or communication was a popular topiconline in this subgroup. While UDL neiplatforms (Basham al., 2010; Lohmann et al., ther requires theet use of technology nor2018). reliesOthers solely explored increasing accessibility of online courses (Scott & on it to enhance pedagogy, implementation is certainTemple, 2017) or by tutorials Hoover, 2015), and de-assisly facilitated the (Webb use of& electronic media, creasing attrition in these courses (Tobin, 2014). Despite the tive technology, and accessible educational materials prevalence online coursework, barriers within them continue to (Meyer etof al., 2014). Several recent articles emphaarise, and instructors must attend to the preferences of students. size these links between UDL and technology, particFor example, a case by Rao and Tannersonline (2011) examined ularly as a tool forstudy designing engaging courses not only the design of courses using UDL to mitigate these2010; or communication platforms (Basham et al., problems, butet also evaluated elements of UDLincreasing design Lohmann al., 2018).which Others explored were perceived as most useful by students. The authors found accessibility of online courses (Scott & Temple, that interaction among students and instructors increased 2017) or tutorials (Webb & Hoover, 2015), and deengagement, and that providing options for expression of creasing attrition in these courses (Tobin, 2014). Delearning also yielded positive perceptions. Rao and Tanner’s spite the prevalence of online coursework, barriers piece is an important one, as it highlights the fact that merely within them continue to arise, and instructors must using technology does not mean UDL is being employed attend to the preferences of students. For example, a case study by Rao and Tanners (2011) examined not only the design of courses using UDL to mitigate these problems, but also evaluated which elements of UDL design were perceived as most useful by students. The authors found that interaction among students and instructors increased engagement, and that providing options for expression of learning also yielded positive perceptions. Rao and Tanner’s piece is an important one, as it highlights the fact that merely using technology does not mean UDL is being em- rather, UDL should UDL be used to intentionally ployed; rather, should be usedandtoproactively intentionally design courses that facilitate learning for variability in and proactively design courses that thatallows facilitate learning expression, representation, and engagement. On arepresentasomewhat that allows for variability in expression, larger scale, UDL implementation has been explored at a tion, and engagement. macro-level, across academic departments. Several studies took On a somewhat larger scale, UDL implementation up the problematic nature of how disability is typically handled on has been explored at a macro-level, across academic campus – that it is a problem with which to deal. For ex- ample, a departments. Several studies took up the problematic study by Beck et al. (2014) looked at how a Disability Services nature of how disability is typically handled on camoffice on a large college campus could align its offerings within a pus – that it is a problem with which to deal. For exUDL framework. The authors found that the office, although ample, a study by Beck et al. (2014) looked at how a aimed at facilitating learning and accommodations for students Disability Services office on a large college campus with disabilities, in fact created a number of physical and modal could align its offerings within a UDL framework. The barriers through their practices. They urged not only a practical authors found that the office, although aimed at facilichange, but a philosophical, reflective, and continuous tating learning andmodel, accommodations forfrom students with consideration of their and ways to move intervention disabilities, in factto created number physical and on behalf of students intentionala support of of faculty and system modal barriers through their practices. They urged design. A study by Fovet et al. (2014), analyzed the outcomes of notextended only aeffort practical change, but philosophical, an to implement UDL on a a college campus. reflective, and continuous consideration of their Faculty indicated that the process included a number of model, and ways to move fromconcerns, intervention onresources, behalf and of stressors, including budgetary depleted students toabout intentional support of faculty andthe system assumptions an increase in workload. However, design. A found studythat byincreased Fovet etcollaboration al. (2014),among analyzed researchers staff the outcomes of an extended effort to implement UDL on eased some of these stressors, and that faculty appreciated the a college campus. Faculty An indicated thatof the process sense of ownership in redesign. assessment the College included Transition, a numberAccess of stressors, including budgetary Supporting and Retention program (College STAR) founddepleted similarly positive resultsand regarding faculty and staff concerns, resources, assumptions about collaboration (Hutson & Downs, 2015). These an increaseandinownership workload. However, the researchers pieces the development of a shift in mindsetstaff of teaching foundsuggest that increased collaboration among eased and learning in higher education, toward problematizing some of these stressors, and that faculty appreciated traditional disability. Rather than thinking ways to the senseviews of of ownership in redesign. An about assessment “deal withCollege disability,” Supporting proactive approaches to inclusive design are of the Transition, Access and fostered through UDL implementation at a systemic level. Using Retention program (College STAR) found similarly UDL to address specific problems and actand as astaff “catalyst for positive results regarding faculty collaborachange” was referred to by one of Moore et al.’s participants as a tion and ownership (Hutson & Downs, 2015). These “Trojan horse” (p. 42). Trojan horses refer to specific issues that pieces suggest the development of a shift in mindset might open theand doorlearning for UDL asina solution. Such issues, toward whether of teaching higher education, systemic issues related to equity and inclusion, or more discrete problematizing traditional views of disability. Rathpedagogical concerns of faculty (e.g., engagement), were evident er than thinking about ways to “deal with disability,” across this subgroup of literature. Whether employed as a proactive approaches to inclusive design are fostered macro-level administrative solution or only within a sole through UDL implementation at a systemic level. instructor’s classroom, these articles indicate the prevalence of Using UDL to address specific problems and act UDL as a potential way to address a range of challenges in as a “catalyst for change” was referred to by one of higher education settings. Moving Forward: UDL Buy-In. Several Moore et al.’s participants as a “Trojan horse” (p. 42). publications focus on moving UDL implementation Trojan horses refer to specific issues that might open the door for UDL as a solution. Such issues, whether systemic issues related to equity and inclusion, or more discrete pedagogical concerns of faculty (e.g., engagement), were evident across this subgroup of literature. Whether employed as a macro-level administrative solution or only within a sole instructor’s classroom, these articles indicate the prevalence of UDL as a potential way to address a range of challenges in higher education settings. Moving Forward: UDL Buy-In. Several publications focus on moving UDL implementation for- Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 33(2) 189 forward in some which typically involves some type ofsome ward in someway, way, which typically involves scaling of UDL implementation. Moore and colleagues (2018), type of scaling of UDL implementation. Moore and while laying out suggestions for levels and processes involved in colleagues (2018), while laying out suggestions for scalability, make an important point that is particularly relevant to levels and processes involved in scalability, make an articles described here: “scaling up at its most fundamental level important point that is particularly relevant to articles may be conceived winning the minds of an described here:as“scaling uphearts at itsand most fundamental ever-expanding group of individuals and providing the support level may be conceived as winning the hearts and structures necessary to sustain them” (p. 49). These publications minds of an ever-expanding group of individuals and recognize the necessity of some degree of philosophical buy-in providing the support structures necessary to sustain on the part of faculty, students, and other stakeholders to them” (p. 49). These publications recognize the nerecognize learner variability as the norm. In other words, cessity of some degree of philosophical buy-in on because UDL is not a program, it cannot be treated like a the part of faculty, students, and other stakeholders checklist of strategies focused only on getting learners to access to recognize learner variability as the norm. In other the curriculum. While it is conceivable that one could “do UDL,” words, because UDL is not a program, it cannot be by implementing multiple means of engagement, representation, treated like a checklist of strategies focused only on and action of expression into classroom practice, this approach getting learners tothat access the curriculum. While it is lacks the intentionality is characteristic of UDL, the conceivable that one could “do UDL,” by implementconnection with an instructional goal, and the focus on student ing multiple meanscontext of engagement, variability in a particular (Lowrey et al., representation, 2017). Several and action of expression classroom practice, this studies examined how studentsinto might buy in to UDL, as approach lacks the intentionality that is characterisexperienced through participation in a course where it was tic of UDL,bythe connection with an instructional goal, implemented faculty. Kumar and Wideman (2014) examined and the focus on student variability in a particular implementation in a first-year undergraduate course, and student context (Lowrey et al.,positive. 2017).Students appreciated the perceptions were generally Several studies howand students flexibility in course design examined and assignments felt that it might buy in to toUDL, as experienced participation contributed their learning and higher through grades than they would in aotherwise course had. where it was implemented faculty. have Faculty reported that taking theby time to consider means of presentation gave them an Kumarmultiple and Wideman (2014) examined implementaappreciation for other ways of learning that would address tion in a first-year undergraduate course, and student learner variability. Likewise, Smith (2012) found that both faculty perceptions were generally positive. Students apand studentsthe reported higher levels of engagement during a preciated flexibility in course design and assignUDL-framed and the relationship wastosomewhat ments andcourse, felt that it contributed their learning reciprocal; in other words, higher student engagement fostered and higher grades than they would have otherwise more engagement on the part of the instructor to link practice had. Faculty reported that taking the time to conwith multiple meansmeans of motivation. Buy-in from both faculty andan sider multiple of presentation gave them students may suggest opportunities for scaling UDL that would appreciation for other ways of learning that would facilitate within a program or institution. As noted in addresssustainability learner variability. Likewise, Smith (2012) the previous section, instructors often draw on UDL in designing found that both faculty and students reported higher online courses to increase both access and engagement. Two levels of engagement during a UDL-framed course, publications, while focused on design of such courses, employed and the relationship was somewhat reciprocal; in a UDL mindset not only as a means, but as a socially just end. other words, higher student engagement fostered This is an important shift. Rogers-Shaw et al. (2018) described more engagement on the part of the instructor to link their process of redesigning the syllabus, assessments, and practice with multiple means of motivation. Buy-in communication, and offering choices in their course for adult from both faculty and students may suggest opporlearners that not only tunities for scaling UDL that would facilitate sustainability within a program or institution. As noted in the previous section, instructors often draw on UDL in designing online courses to increase both access and engagement. Two publications, while focused on design of such courses, employed a UDL mindset not only as a means, but as a socially just end. This is an important shift. Rogers-Shaw et al. (2018) described their process of redesigning the syllabus, assessments, and communication, and offering choices in their course for adult learners that not only increase butbut alsoalso urged them them to reflect on their own increaseaccess, access, urged to reflect on their assumptions as they applied UDL principles. Likewise, Morra and own assumptions as they applied UDL principles. Reynolds (2010) acknowledged similar(2010) shifts in acknowledged their design of Likewise, Morra and Reynolds technology-enhanced courses, noting that practical shifts must similar shifts in their design of technology-enhanced be accompanied by philosophical changes in beliefs courses, noting that practical shifts must be about accompalearning. then, they argue, will UDL facilitate inclusion nied byOnly philosophical changes in truly beliefs about learnof students who have traditionally been marginalized on college ing. Only then, they argue, will UDL truly facilitate campuses. This subgroup of literature suggests that UDL is inclusion of students who have traditionally been being operationalized in a variety of ways, in response to a range marginalized on college campuses. of challenges, and is doing so with varying degrees of support This subgroup of literature suggests that UDL across postsecondary settings. While findings of this group of is being operationalized in a variety of ways, in reliterature reflect a spectrum of reasons for implementing UDL, it sponse to a range of challenges, and is doing so with is important to highlight the presence of the common thread also varying degrees of support across postsecondary setnoted by Moore and colleagues (2018): human buy-in – from tings. While findings of this group of literature reflect faculty, students, and stake- holders across the system – will a spectrum of reasons for implementing UDL, it is ultimately determine not only the scale of implementation, but its important to highlight the presence of the common success and sustainability. thread also noted by Moore and colleagues (2018): human buy-in – from faculty, students, and stakeholders across the system – will ultimately determine not only the scale of implementation, but its success and sustainability. Conceptualizing UDL Our second researchresearch question sought to understand in Our second question sought the to ways underwhich researchers in higher education standfaculty the and ways in which faculty and conceptualize researchers UDL. This subgroup of literature includes conceptual, in higher education conceptualize UDL. This subdescriptive, and empirical pieces. Overall, across articles, group of literature includes conceptual,these descriptive, researchers conceptualize UDL as a framework for inclusive and empirical pieces. Overall, across these articles, pedagogy or instructional design, UDL often leveraging technological researchers conceptualize as a framework for innovations meet the needs a diverse student population, inclusive topedagogy or of instructional design, often including those technological with labeled disabilities. Several publications leveraging innovations to meet the examined philosophical underpinnings of UDL, either including to disrupt needs of a diverse student population, the discourse of normalcy that tends to undergird instructional those with labeled disabilities. and pedagogical practices in higher education (Liasidou, 2014) Several publications examined philosophical un-or to conceptualize how the framework might address issues of derpinnings of UDL, either to disrupt the discourse inequity or exclusion in higher education. While issues of of normalcy that tends to undergird instructional and pedagogy, design, and equity were incorporated into studies pedagogical practices in higher education (Liasidou, addressed by the first research question, these pieces are 2014) or to conceptualize how the framework might distinct in that they are not focused on practical implementation of address issues of inequity or exclusion in higher edUDL. Rather, publications in this group focus on either faculty or ucation. While issues of pedagogy, design, and eqstudent perceptions and understanding of UDL in postsecondary uity were incorporated into studies addressed by the settings. Some of this work appears to be situated within a critical first research question, these pieces are distinct in that or social model of disability. The social model was they are not focused on practical implementation of conceptualized by Oliver (2013) as an alternative to the dominant UDL. model, Rather,which publications in this focusdeficit. on eimedical defines disability as group an individual ther faculty or student perceptions and understanding Social models situate the dominant view of disability as one of UDL settings. created by in thepostsecondary economic and social forces that render certain of as this work and appears to be situated within a typesSome of bodies deficient subsequently less critical or social model of disability. The social model was conceptualized by Oliver (2013) as an alternative to the dominant medical model, which defines disability as an individual deficit. Social models situate the dominant view of disability as one created by the economic and social forces that render certain types of bodies as deficient and subsequently less de- 190 Fornauf & Erickson; Inclusive Pedagogy students doesdoes not gonot far enough support to them. These desirable (Baglieri, 2019). Versions of the of social disabled students go far toenough support sirable (Baglieri, 2019). Versions themodel socialhave model disabled positive perceptions of UDL may require a been by educational scholars whoscholars have problematized them. suggest These that studies suggest that positive perceptions haveexplored been explored by educational who have studies shift in mindset in order to facilitate buy-in and sustainability. the narrow understanding of individual disability in educational problematized the narrow understanding of individu- of UDL may require a shift in mindset in orderInto words, buy-in negative and viewssustainability. toward students with disabilities or settings and attempted to deepen settings the impactand of reframing facilitate In other words, al disability in educational attempted to other those requiring accommodations can act as a barrier for teaching and learning within a more social framework (Baglieri, deepen the impact of reframing teaching and learn- negative views toward students with disabilities or successful implementation of UDL. As with literature 2019; Linton, 1998). That said, viewing disability solely as 2019; a ing within a more social framework (Baglieri, those requiring accommodations can act asona barrier operationalizing UDL, these attitudes tend be a key component of social phenomenon, and denying the experiences of disabled Linton, 1998). That said, viewing disability solely as for successful implementation of UDL. As with literUDL as a positive force in higher education. The individuals is also problematic; Some researchers have a social phenomenon, and denying the experiences conceptualizing ature on operationalizing UDL, these attitudes tend suggested that UDL must be careful to acknowledge the reality of remaining pieces we will discuss focused on the “why” behind of disabled individuals is also problematic; Some re- be a key component of conceptualizing UDL as a disability and the disablement process, without erasing disability UDL. These pieces, while conceptualizing UDL as a broad searchers have suggested that UDL must be careful to positive force in higher education. solution to poor learning outcomes in higher education, make the as a positive element of identity (Dolmage, 2015). The role of acknowledge the reality of disability and the disableThe remaining pieces we will discuss focused case for embracing UDL in a variety of ways. While several of support services for students with identified disabilities ment process, without erasing disability as a positive on the “why” behind UDL. These pieces, while conthese focused on facets of instructional design (Vininsky & Saxe, complicates execution of a social model, as several of these element of identity (Dolmage, 2015). ceptualizing UDL as a broad solution to poor learn2016; Williams et al., 2013) and neuroscience (Schreiner et al., pieces explore. Liasidou (2014), for example argues that such The role of support services for students with idening outcomes in higher education, make the case for services, which often serve to ensure that students are receiving 2013), others emphasized student learning as the conceptual tified disabilities complicates execution of a social focus embracing UDL in a variety of ways. While severof UDL. One of the earliest publications was a conceptual reasonable accommodations serve to further marginalize and model, as several of these pieces explore. Liasidou al of these focused on afacets design piece that essentially offered primerof forinstructional faculty on how to stigmatize disabled students. Accommodations often involve (2014), for example argues that such services, which (Vininsky & Saxe, 2016; Williams et al., 2013) and retrofitting assignments or assessment, and do not consider the incorporate UDL into assessment (Ofiesh et al., 2006). often serve to ensure that students are receiving reaneuroscience (Schreiner et al., 2013), others emexperience of the disabled individual at the outset. This function, Suggestions included backward design, so that instructors sonable accommodations serve to further marginalize phasized learning theintended conceptual focus theystudent were teaching whatas they to assess, andof a she argues, upholds the discourse of normalcy requiring students ensured and stigmatize disabled students. Accommodations UDL. One of the earliest publications was a conceplist of ways to make assessments themselves accessible through to self-disclose potentially stigmatizing information that often involve retrofitting assignments assessment, tual piece essentially a primer faculty visual design that of images and text,offered clear language, andfor layout. In perpetuates the myth of disability as a deficit in or need of and do not consider the experience of the disabled on how to incorporate UDL into assessment (Ofiesh addition, this piece, along with a seminal piece by CAST remediation so that one can become normal. This finding was individual at and the Mole outset. This function, she argues, et al., 2006). included backward design, DavidSuggestions Rose and colleagues, focuses on student echoed by Fovet (2013), whose qualitative study found co-founder upholds the discourse of normalcy requiring so that(Rose instructors ensured were teaching what learning et al., 2006). Thesethey publications get at the crux of that UDL offered faculty a common language with whichstudents to to self-disclose potentially stigmatizing information theyUDL intended to assess, list of ways to make aswhy is markedly differentand fromaaccommodations: UDL theory approach a diverse student body, not solely as a vehicle for that perpetuates the myth of disability as a deficit sessments themselves accessible a more transformative approach through to creatingvisual deservice delivery or accommodations related to disability. Thus, in proposes instructional environments that promote learning, over these offer a model for conceptualizing UDL normal. beyond needtwo of pieces remediation so that one can become sign of images and text, clear language, and layout. traditionally associated with piece by Disability Services or even in response to a and “problem,” This finding was echoed by Fovet Moleand (2013), individualistic In addition,approaches this piece, along with a seminal of disability. David Furthermore, update of Rose andfoinstead it as astudy way tofound transform higher education a remediation whoseconsider qualitative that UDL offeredinto facCAST co-founder Roseanand colleagues, 2008) piece published in 2015 highlights the more and equitable space. studies attempted to ulty inclusive a common language withSeveral which to approach a colleagues’ cuses on (2006, student learning (Rose et al., 2006). These changes made not only to course designs, but to UDL theory at understand perceptions of UDL, and beliefs about disability or diverse student body, not solely as a vehicle for ser- publications get at the crux of why UDL is markedlarge (Gravel et al., 2015). The iterative nature of UDL suggests related accommodations. For example, Black et al. (2014) vice delivery or accommodations related to disability. ly different from accommodations: UDL theory proneither implementation nor conceptualization is a identified teaching practices UDLfor at aconceptuuniversity, that poses a more transformative approachoftoUDL creating Thus, these two piecesconsistent offer a with model event, but rather a process of continuing reflection and and also explored faculty attitudes toward students with instructional environments that promote learning, alizing UDL beyond Disability Services or even in static refinement as the landscape of postsecondary education disabilities. They found that faculty with limited or some training response to a “problem,” and instead consider it as a over individualistic approaches traditionally associto develop and change. inway UDLto had no significant effecteducation on the frequency incorporating ated with remediation of disability. Furthermore, an transform higher into aofmore inclu- continues UDL principles, but those with more experience tended to update of Rose and colleagues’ (2006, 2008) piece sive and equitable space. incorporate UDLstudies more consistently. exploring student Several attemptedStudies to understand percep- published in 2015 highlights the changes made not perceptions had slightly different findings. While a study from tions of UDL, and beliefs about disability or related only to course d esigns, but to UDL theory at large Belgium indicated that consistent application of UDL may actually accommodations. For example, Black et al. (2014) (Gravel et al., 2015). The iterative nature of UDL create barriers for students without disabilities (Griful-Freixenet et identified teaching practices consistent with UDL at a suggests that neither implementation nor conceptual., 2017), a study by Black et al. (2015) highlight- ed UDL’s university, and also explored faculty attitudes toward alization of UDL is a static event, but rather a proapplicability for a variety of students, emphasizing that simply students with disabilities. They found that faculty cess of continuing reflection and refinement as the adding accommodations for with limited or some training in UDL had no signif- landscape of postsecondary education continues to icant effect on the frequency of incorporating UDL develop and change. principles, but those with more experience tended to incorporate UDL more consistently. Studies explorDiscussion ing student perceptions had slightly different findings. includedincluded here represent diverse field of research on While a study from Belgium indicated that consis- The pieces The pieces here arepresent a diverse field of UDL higher tent application of UDL may actually create barriers the of implementation research on and the conceptualization implementation and inconceptualeducation. UDL’s iterative nature suggests a willingness on the for students without disabilities (Griful-Freixenet et ization of UDL in higher education. UDL’s iterative part of those who take it up to create and sustain inclusive al., 2017), a study by Black et al. (2015) highlight- nature suggests a willingness on the part of those who andcreate in someand casessustain to acknowledge established ed UDL’s applicability for a variety of students, em- environments, take it up to inclusive environphasizing that simply adding accommodations for ments, and in some cases to acknowledge established Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 33(2) 191 norms ability and access within higher education. many normsof of ability and access within higher While education. cases be made forcan the employment of the UDL,employment either as a of Whilecanmany cases be made for response to challenges or as anto end in and of itself, UDL, either as a response challenges or astheanliterature end in discussed here suggests that UDL is interpreted many as that a and of itself, the literature discussed herebysuggests framework and by others as an intervention. In addition, its use UDL is interpreted by many as a framework and by as a wayas to facilitate inclusive pedagogy and disrupt others an intervention. In addition, its usetheas a way normative center of education, while evident in theory (e.g., to facilitate inclusive pedagogy and disrupt the normaBaglieri, Valle et al., 2011; Meyer et al., 2014), has yet to be tive center of education, while evident in theory (e.g., consistently explored in UDL literature. UDL provides the opportunity to foreground disability in designing UDL provides the opportunity to foreground disabilcurriculum and pedagogy. In other words, UDL can compel ity in designing curriculum and pedagogy. In other faculty to consider a “systematic negotiation needs across any words, UDL can compel faculty to ofconsider a “sysassembly of student differences” as they design their courses tematic negotiation of needs across any assembly of and instructional materialsas (Mitchell et al., 2014, 309). student differences” they design theirp. courses and Unpacking the history of Universal Design in higher education, instructional materials (Mitchell et al., 2014, p. 309). Dolmage (2017) also emphasized this active part of UDL: the Unpacking the history of Universal Design in higher design process. education, Dolmage (2017) also emphasized this acBaglieri, Valle et al., 2011; Meyer et al., 2014), has yet tive part of UDL: the design process. to be consistently explored in UDL literature. This dimension suggests that UDthat is a way to Thisactive active dimension suggests UDtoisplan, a way foresee, to imagine the future. The "Universal" of UD also UDL: Intervention or Framework? to plan, to foresee, to imagine the future. The suggests that disability something that that is always a part ofis In many across the two subgroups of literature UDLof Inpublications many publications across the two subgroups "Universal" of UDisalso suggests disability our worldview.that Thus, UD a is part successful, is hopeful was depicted UDL as a response to a particular problem ortoline of literature was depicted as a response a particsomething iswhen always of ourit worldview. and realistic – allowing teachers to structure space and inquiry. Recognizing in some cases such an approachthat may in ular problem orthat line of inquiry. Recognizing Thus, when UD is successful, it is hopeful and repedagogy in the broadest possible manner, Universal result in wider buyin from faculty and administration, or a more some cases such an approach may result in wider buyalistic – allowing teachers to structure space and Design is not in about it ispossible about building – building cohesive agenda for change (Moore et al., 2018), in from faculty and administration, or apotential more cohepedagogy thebuildings, broadest manner, Unicommunity, building better pedagogy, building opportunities drawbacks also exist. UDL’s use as an intervention to ameliorate sive agenda for change (Moore et al., 2018), potentiala versal Design is not about buildings, it is about for agency. It is a way to move. (p. 118) problem may further productive of UDL, as drawbacks alsocomplicate exist. UDL’s use use as an intervention building – building community, building better interventions are traditionally done to students instructors, proor to to ameliorate a problem may further by complicate pedagogy, building opportunities for agency. It is curriculum faculty; the emphasis remains onare the traditionally teacher rather ductive by use of UDL, as interventions a way to move. (p. 118) than the learner, which by getsinstructors, away from theor purpose and aims ofby done to students to curriculum UDL. Another possible drawback of framing in response to Conceptualizing UDL as a response to problems caused by the faculty; the emphasis remains on studies the teacher rather Conceptualizing UDL as a response to problems the problem of struggling students with disabilities, is that the students isof inherently it focuses only than the learner, which gets away from the purpose presence caused of bycertain the presence certainlimiting; students is inhernotion that there is some internal deficit in the students that UDL particular groups students. The on promise of UDL groups in higherof and aims of UDL. Another possible drawback of on ently limiting; it offocuses only particular can fix is perpetuated; issues of design are neglected. This is in its possibility; the process allows us to imagine framing studies in response to the problem of strug- education students. The promise of UDL in higher education not is concern was echoed by CAST researchers in 2015. Revisiting only making access universal, but learning as well. Positioning gling students with disabilities, is that the notion that in its possibility; the process allows us to imagine not Rose et al.’s (2006) work specific to UDL in higher education, a process-based framework rather than an intervention there is some internal deficit in the students that UDL UDL onlyasmaking access universal, but learning as well. Gravel and colleagues (2015) recognized that the previous piece allows us to acknowledge disabling environments and center the can fix is perpetuated; issues of design are neglected. Positioning UDL as a process-based framework had still situated problems with learning partially in the learn- er experiences of students with disabilities in our design. This concern was echoed by CAST researchers lived rather than an intervention allows us to acknowledge and partially in the environment; they amended this view in their Furthermore, IHEs can incorporate variation not only in perceived in 2015. Revisiting Rose et al.’s (2006) work specific disabling environments and center the lived expericonclusion. Stating their discomfort with emphasizing problems ability, but in language, race, gender, etc., without assuming the to UDL in higher education, Gravel and colleagues ences of students with disabilities in our design. Furwithin individuals, Gravel et al. asserted that “It is our learning default position of a heteronormative, able-bodied individual as (2015) recognized that the previous piece had still thermore, IHEs can incorporate variation only in environments, first and foremost, that are disabled. Addressing the the standard toward which a UDL intervention couldnot remediate situated problems with learning partially in the learnperceived ability, but in language, race, gender, etc., disabilities in the learning environment…will make courses that are students. er and partially in the amended without assuming the default position of a heteronorbetter not just for students with environment; disabilities, but forthey all students”(p. this view inframing their disability conclusion. Stating their mative, able-bodied individual as the standard toward 99). This shift in suggests a move awaydiscomfrom a fort with emphasizing problems within individuals, which a UDL intervention could remediate students. deficit-based perspective and illustrates the continually evolving Gravel et al. asserted that “It is our learning environunderstandings of UDL. We agree with Gravel et al. and others ments, first&and thatthat areUDL disabled. Address- Disrupting the Discourse of Normalcy (e.g., Waitoller Kingforemost, Thorius, 2016) theory and ing thecan disabilities learning environment…will Publications in both the operationalizing and conresearch and should in do the more to challenge existing notions of Publications in both the operationalizing and conceptualizing make areeducational better notcontexts. just for We students with strands ceptualizing addressshift theraised philosophical ability andcourses normalcythat across highlight address strands the philosophical by Moore andshift disabilities, but chapter for allhere students”(p. 99). This Gravel et al.’s (2015) because it focuses on the shift colleagues (2018) that winning the hearts and minds raised by Moore andmentioned colleagues (2018) that mentioned in framing disabilityand suggests a moveUDL. away from a of process of conceptualizing operationalizing Furthermore, faculty. Implementation an institution cannot be a winning the hearts andwithin minds of faculty. Implementawedeficit-based concur with scholars Disability and Studies in Education perspective illustrates the(Dolmage, contin- practical project and in order to be will require tion within analone, institution cannot beeffective a practical project 2017; Mitchell et al., 2014) who argue thatof UDL. We agree some ability, disability, andrequire variability. ually evolving understandings alone,reconceptualization and in order toofbe effective will some concepts, it seems, are murkier in higher education than with Gravel et al. and others (e.g., Waitoller & King These reconceptualization of ability, disability, and variabilin K-12, where notions of ability and disability are highly normed Thorius, 2016) that UDL theory and research can and ity. These concepts, it seems, are murkier in highregulated (for better worse)where and often discussed a should do more to challenge existing notions of abili- and er education than inorK-12, notions of as ability result of special education. Still,normed winning hearts and minds does ty and normalcy across educational contexts. and disability are highly and regulated (for seem to go far enough to yield a philosophical shift that We highlight Gravel et al.’s (2015) chapter here not better or worse) and often discussed as a result of truly disrupt a discourse of normalcy and result in because it focuses on the process of conceptualizing would special education. and operationalizing UDL. Furthermore, we concur Still, winning hearts and minds does not seem to with scholars Disability Studies in Education (Dol- go far enough to yield a philosophical shift that would mage, 2017; Mitchell et al., 2014) who argue that truly disrupt a discourse of normalcy and result in in- 192 Fornauf & Erickson; Inclusive Pedagogy well asas a need to examine outcomes of UDL, focusing solely on inclusive ForFor example, Beck Beck and colleagues (2014) well a need to examine outcomes of UDL, focusclusivepedagogy. pedagogy. example, and colleagues the effects of UDL as an intervention compromise its intention as considered that, as faculty areas in positions of power within IHEs, (2014) considered that, faculty are in positions of ing solely on the effects of UDL as an intervention framework. Because UDL theory consistent with elements of attending to their re-conceptualizations who isre-conceptualnormal and able acompromise its intention as ais framework. power within IHEs, attending tooftheir the social model of disability, further empirical search linking isizations critical; normalizing discourse is easily internalized by both Because UDL theory is consistentre-with elements of who is normal and able is critical; normalthe fields of disability studies and UDL in higher education is faculty and students. As a result, critical elements need to be izing discourse is easily internalized by both faculty of the social model of disability, further empirical reThe prevalence of ability as the central axis of embedded into theAs process of UDLcritical adoptionelements (Liasidou, 2014). search linking the fields of disability studies and UDL and students. a result, need to warranted. Some scholars have suggested that UDL must actively dismantle teaching and learning within postsecondary settings must be be embedded into the process of UDL adoption (Li- in higher education is warranted. The prevalence ability-centric practices that permeate formal education (Waitoller critically examined and disrupted, and UDL offers a practical asidou, 2014). Some scholars have suggested that of ability as the central axis of teaching and learn& King Thorius, 2016). In higher education, such practices are so approach for taking up this work. Furthermore, the perspectives UDL must actively dismantle ability-centric practic- ing within postsecondary settings must be critically of scholars and students with disabilities need greater deeply ingrained into institutions based on perceived levels of es that permeate formal education (Waitoller & King representation examined and disrupted, and UDL offers a practical in order to understand how and if UDL can ability that it is taken-for-granted as normal. Instead of simply Thorius, 2016). In higher education, such practices approach for taking up this work. Furthermore, the trying to remove barriers to learning for certain students (such as operate as a framework that acknowledges disability as an are so deeply ingrained into institutions based on per- perspectives of scholars and students with disabilithose with disabilities), the existence of the barriers must first be agentive and positive aspect of identity (Dolmage, 2015). In ceived levels of ability that it is taken-for-granted as addition, ties need greater representation in order to understand the research presented here suggests room for growth questioned, and the sources of their existence identified normal. Instead of simply trying to remove barriers how and if UDL can operate as a framework that ac(Waitoller & King Thorius, 2016). There is limited evidence from in the scope of UDL practice. Much of the work has been done to learning for certain students (such as those with within knowledges disability as of aneducation agentiveatand positive asdepartments or colleges the postsecondary articles in this review that UDL in higher education is being disabilities), the existence of the barriers must first be pect of identity (Dolmage, 2015). level. This is unsurprising, given that faculty in education likely conceptualized as an avenue for inclusive pedagogy that questioned, and the sources of theirabilities existence identi- have In addition, the with research presented here sugthe most experience both pedagogy and student considers educating students with diverse as a justifiable fied (Waitoller & King Thorius, 2016). gests room for growth in the scope of UDL practice. variability. That said, there is a great opportunity for UDL end, student variability at the outset of course design, and There isasset. limited evidence fromsurprising, articlesasinUDL this research Much of the work has been done those within departments in other disciplines, particularly which may have disability as an This is not altogether review that UDL in higher education is being conor colleges of education at the postsecondary level. historically prioritized content. Lastly, the interpretation of UDL in research in general is still at an emerging stage with regard to ceptualized as an avenue for inclusive pedagogy that This is unsurprising, given that faculty in education higher education here is further limited by instructional methods both K-12 teachers and university faculty. Yet the variety of UDL considers educating students diverse likely have theAnd most experience with both pedagoenvironments. yet learning happens in so many settings research illustrated here suggests thatwith there is growing abilities interest in and as a justifiable student in variability at the outset ingy and education: student variability. That said, thereoperational is a great higher in meetings, at events, through transforming accessend, and pedagogy postsecondary settings, of course design, disabilityofas an asset. This is systems. opportunity for UDL research in otherat adisciplines, More research needs to be conducted systems and in disrupting limitedand interpretations inclusion that rely In other words, might may we go have from simply adopting prithe not altogether surprising, as UDL research in gener- level. particularly thosehow which historically solely on accommodations. It seems appropriate to consider framework to intentionally grounding our core beliefs in UDL al isanstill at anpedagogy emerging with oritized content. regard to both UDL what inclusive mightstage look like within courses, theoryLastly, and practice - as instructors, programs, programs, and departments, and howfaculty. faculty might on the interpretation of UDL department, in higher and eduK-12 teachers and university Yet draw the variety institutions? UDL should not be limited to the classroom, its elements the UDL framework to designsuggests an intentional methof UDLofresearch illustrated here that there cation here is further limited by instructional and is dependent onAnd those yet wholearning embrace it,happens extendingin it approach that continues with an ever-changing ods and environments. is growing interest to inevolve transforming access andstudent ped- sustainability broader socialin realm to increase inclusive body, andin new developments insettings, research. and in disrupting into so the many settings higher education: in pedagogies meetings, in at agogy postsecondary formalthrough and informal ways. events, operational systems. More research limited interpretations of inclusion that rely solely both on accommodations. It seems appropriate to consider what an inclusive pedagogy might look like within courses, programs, and departments, and how faculty might draw on elements of the UDL framework to design an intentional approach that continues to evolve with an ever-changing student body, and new developments in research. Implications ThereThere are several importantimportant implicationsimplications here for furtherhere for are several research. First, because UDL has been clearly defined through further research. First, because UDL has been clearwork from CAST, researchers drawing on CAST’s framework ly defined through work from CAST, researchers should take on careCAST’s to be consistent in descriptions UDL care to drawing framework shouldoftake concepts, principles, and guidelines. Such consistency would be consistent in descriptions of UDL concepts, prinserve to demonstrate the many ways UDL might be used across ciples, and guidelines. Such consistency would serve a number of different contexts, and further emphasize that UDL to demonstrate the many ways UDL might be used can be adapted to meet the needs of highly variable student across a number of different contexts, and further empopulations. This means staying true to an emphasis on phasize that UDL can be adapted to meet the needs of variability and inclusiveness, rather than disability and highly variable student populations. This means stayintervention. While, in the climate of accountability, there is a ing true to an emphasis on variability and inclusivetemptation as ness, rather than disability and intervention. While, in the climate of accountability, there is a temptation as needs to be conducted at a systems level. In other words, how might we go from simply adopting the UDL framework to intentionally grounding our core beliefs in UDL theory and practice - as instructors, programs, department, and institutions? UDL should not be limited to the classroom, and its sustainability is dependent on those who embrace it, extending it into the broader social realm to increase inclusive pedagogies in both formal and informal ways. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 33(2) 193 References Al-Azawei, A., Serenelli, F., & Lundqvist, K. 2016). Universal design for learning (UDL): A content analysis of peer-reviewed journal papers from 2012 to 2015. Journal of the Scholarship of eaching and Learning, 16(3), 39–56. Baglieri, S., Bejoian, L. M., Broderick, A. A., Connor, D. J., & Valle, J. (2011). [Re]claiming inclusive education. Teachers College Record, 113, 2122-2154. Baglieri, S. (2017). Disability studies and the inclusive classroom: Critical practices for creating least restrictive attitudes. Routledge. Baglieri, S., Valle, J. W., Connor, D. J., & Gallagher, D. J. (2011). Disability studies in education: The need for a plurality of perspectives on disability. Remedial and Special Education, 32, 267-278. Basham, J. D., Lowrey, K. A., & deNoyelles, A. (2010). Computer mediated communication in the universal design for learning framework for preparation of special education teachers. Journal of Special Education Technology, 25(2), 31–44. Beck, T., Diaz del Castillo, P., Fovet, F., Mole, H., & Noga, B. (2014). Applying universal design to disability service provision: Outcome analysis of a universal design (UD) audit. Journal of Postsecondary Education And Disability, 27, 209-222. Bernacchio, C., Ross, F., Washburn, K. R., Whitney, J., & Wood, D. R. (2007). Faculty collaboration to improve equity, access, and inclusion in higher education. Equity & Excellence in Education, 40, 56–66. Black, R. D., Weinberg, L. A., & Brodwin, M. G. (2014). Universal design for instruction and learning: A pilot study of faculty instructional methods and attitudes related to students with disabilities in higher education. Exceptionality Education International, 24, 48-64. Black, R. D., Weinberg, L. A., & Brodwin, M. G. (2015). Universal design for learning and instruction: Perspectives of students with disabilities in higher education. Exceptionality Education International, 25(2), 1-16. Capp, M. J. (2017). The effectiveness of universal design for learning: A meta-analysis of literature between 2013 and 2016. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 21, 791–807. CAST (2018). Universal design for learning guidelines version 2.2. Retrieved from http://udlguidelines.cast.org Cosier, M., & Ashby, C. E. (2016). Disability studies and the “work” of educators. In M. Cosier, & C. E. Ashby (Eds.), Enacting change from within: Disability studies meets teaching and teacher education (pp. 1-20). Peter Lang. Davies, P. L., Schelly, C. L., & Spooner, C. L. (2013). Measuring the effectiveness of universal design for learning intervention in postsecondary education. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 26, 195–220. Dean, T., Lee-Post, A., & Hapke, H. (2017). Universal design for learning in teaching large lecture classes. Journal of Marketing Education, 39(1), 5-16. Dolmage, J. (2015). Universal design: Places to start. Disability Studies Quarterly, 35(2). Dolmage, J. (2017). Academic ableism: Disability and higher education. University of Michigan Press. Evans, C., Williams, J. B., King, L., & Metcalf, D. (2010). Modeling, guided instruction, and application of UDL in a rural special education teacher preparation program. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 29(4), 41–48. Evmenova, A. (2018). Preparing teachers to use universal design for learning to support diverse learners. Journal of Online Learning Research, 4, 147–171. Fovet, F., Jarrett, T., Mole, H., & Syncox, D. (2014). Like fire to water: Building bridging collaborations between disability service providers and course instructors to create user friendly and resource efficient UDL implementation material. Collected Essays on Learning and Teaching, 7(1), 68-75. Fovet, F., & Mole, H. (2013). UDL--From disabilities office to mainstream class: How the tools of a minority address the aspirations of the student body at large. Collected Essays on Learning and Teaching, 6, 121–126. Gabel, S. L. (Ed.). (2005). Disability studies in education: Readings in theory and method. Peter Lang. Gradel, K., & Edson, A. J. (2010). Putting universal design for learning on the higher ed agenda. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 38, 111–121. Gravel, J. W. (2017). A disciplined application of universal design for learning (UDL): Supporting teachers to apply UDL in ways that promote disciplinary thinking in English language arts (ELA) among diverse learners. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Harvard Graduate School of Education. Gravel, J. W., Edwards, L. A., Buttimer, C. J., & Rose, D. H. (2015). Universal design for learning in postsecondary education: Reflections on principles and their application. In S. E. Burgstahler (Ed.) Universal design in higher education: From principles to practice (2nd ed.), (pp. 81-100). Harvard Education Press. 194 Fornauf & Erickson; Inclusive Pedagogy Griful-Freixenet, J., Struyven, K., Verstichele, M., & Andries, C. (2017). Higher education students with disabilities speaking out: perceived barriers and opportunities of the universal design for learning framework. Disability & Society, 32, 1627-1649. Heelan, A., Halligan, P., & Quirke, M. (2015). Universal design for learning and its application to clinical placements in health science courses (practice brief). Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 28, 469–479. Hehir, T. (2002). Eliminating ableism in education. Harvard Educational Review, 72(1), 1–32. Hehir, T. (2009). Policy foundations of universal design for learning. In D. T. Gordon, J. W. Gravel & L. A. Schifter (Eds.), A policy reader in universal design for learning (pp. 35-45). Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press. Hutson, B., & Downs, H. (2015). The college STAR faculty learning community: Promoting learning for all students through faculty collaboration. Journal of Faculty Development, 29(1), 25-32. Izzo, M. V., Murray, A., & Novak, J. (2008). The faculty perspective on universal design for learning. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 21, 60-72. Kumar, K. (2011). A learner-centered mock conference model for undergraduate teaching. Collected Essays on Learning and Teaching, 420-24. Kumar, K. L., & Wideman, M. (2014). Accessible by design: Applying UDL principles in a first year undergraduate course. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 44, 125-147. Liasidou, A. (2014). Critical disability studies and socially just change in higher education. British Journal of Special Education, 41, 120-135. Linton, S. (1998). Claiming disability: Knowledge and identity. NYU Press. Lohmann, M. J., Boothe, K. A., Hathcote, A. R., & Turpin, A. (2018). Engaging graduate students in the online learning environment: A universal design for learning (UDL) approach to teacher preparation. Networks: An Online Journal for Teacher Research, 20(2). Lowrey, K. A., Hollingshead, A., & Howery, K. (2017). A closer look: Examining teachers' language around UDL, inclusive classrooms, and intellectual disability. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 55, 15-24. McGuire, J. M., Scott, S. S., & Shaw, S. F. (2006). Universal design and its applications in educational environments. Remedial and special education, 27, 166-175. Meyer, A., Rose, D. H., & Gordon, D. T. (2014). Universal design for learning: Theory and practice. CAST Professional Publishing. Miller, D. K., & Lang, P. L. (2016). Using the universal design for learning approach in science laboratories to minimize student stress. Journal of Chemical Education, 93, 1823-1828. Mitchell, D., Snyder, S., & Ware, L. (2014). "[Every] child left behind": Curricular cripistemologies and the crip/queer art of failure. Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies, 8, 295-314. Moore, E. J., Smith, F. G., Hollingshead, A., & Wojcik, B. (2018). Voices from the field: Implementing and scaling-up universal design for learning in teacher preparation programs. Journal of Special Education Technology, 33, 40-53. Morra, T., & Reynolds, J. (2010). Universal design for learning: Application for technology-enhanced learning. Inquiry, 15, 43-51. Nielsen, D. (2013). Universal design in first-year composition--Why do we need it, how can we do it? CEA Forum, 42(2), 3-29. Ofiesh, N. S., Rojas, C. M., & Ward, R. A. (2006). Universal design and the assessment of student learning in higher education: Promoting thoughtful assessment. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 19, 173-181. Ok, M. W., Rao, K., Bryant, B. R., & McDougall, D. (2017). Universal design for learning in pre-k to grade 12 classrooms: A systematic review of research. Exceptionality, 25, 116–138. Oliver, M. (2013). The social model of disability: Thirty years on. Disability & Society, 28, 1024-1026. Pearson, M. (2015). Modeling universal design for learning techniques to support multicultural education for pre-service secondary educators. Multicultural Education, 22(3/4), 27-34. Rao, K., Ok, M. W., & Bryant, B. R. (2014). A review of research on universal design educational models. Remedial and Special Education, 35, 153–166. Rao, K., & Tanners, A. (2011). Curb cuts in cyberspace: Universal instructional design for online courses. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 24, 211-229. Roberts, K. D., Park, H. J., Brown, S., & Cook, B. (2011). Universal design for instruction in postsecondary education: A systematic review of empirically based articles. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 24, 5-15. Rogers-Shaw, C., Carr-Chellman, D. J., & Choi, J. (2018). Universal design for learning: Guidelines for accessible online instruction. Adult Learning, 29, 20–31. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 33(2) 195 Rose, D. H., Harbour, W. S., Johnston, C. S., Daley, S. G., & Abarbanell, L. (2006). Universal design for learning in postsecondary education: Reflections on principles & and their application. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 19, 135–151. Rose, D. H., Harbour, W. S., Johnston, C. S., Daley, S. G., & Abarbanell, L. (2008). Universal design for learning in postsecondary education: Reflections on principles & and their application. In S. Burgstahler & R. Cory (Eds.), Universal design in higher education: From principles to practice (pp. 45-59). Harvard Education Press. Rose, D. H., & Meyer, A. (2002). Teaching every student in the digital age: Universal design for learning. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Schelly, C. L., Davies, P. L., & Spooner, C. L. (2011). Student perceptions of faculty implementation of universal design for learning. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 24, 17-30. Schreiner, M. B., Rothenberger, C. D., & Sholtz, A. J. (2013). Using brain research to drive college teaching: Innovations in universal course design. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 24(3), 29-50. Scott, L., & Temple, P. (2017). A conceptual framework for building UDL in a special education distance education course. Journal of Educators Online, 14(1). Scott, L. A., Temple, P., & Marshall, D. (2015). UDL in online college coursework: Insights of infusion and educator preparedness. Online Learning, 19(5), 99-119. Scott, L. A., Thoma, C. A., Puglia, L., Temple, P., & D'Aguilar, A. (2017). Implementing a UDL framework: A study of current personnel preparation practices. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 55, 25-36. Smith, F. G. (2012). Analyzing a college course that adheres to the universal design for learning (UDL) framework. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 12(3), 31-61. Taylor, S. J. (1988). Caught in the continuum: A critical analysis of the principle of the least restrictive environment. Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps, 13, 41-53. Tobin, T. J. (2014). Increase online student retention with universal design for learning. Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 15(3), 13–24 UDL on Campus. (n.d.). Retrieved from www.udloncampus.org. Vininsky, H., & Saxe, A. (2016). The best of both worlds: A proposal for hybrid teacher education. McGill Journal of Education, 51, 1187-1196. Waitoller, F. R., & King Thorius, K. A. (2016). Cross-pollinating culturally sustaining pedagogy and universal design for learning: Toward an inclusive pedagogy that accounts for dis/ability. Harvard Educational Review, 86, 366-389. Webb, K. K., & Hoover, J. (2015). Universal design for learning (UDL) in the academic library: A methodology for mapping multiple means of representation in library tutorials. College & Research Libraries, 76, 537–553. Williams, J., Rice, R., Lauren, B., Morrison, S., Van Winkle, K., & Elliott, T. (2013). Problem-based universal design for learning in technical communication and rhetoric instruction. Journal of Problem Based Learning in Higher Education, 1, 247-261. About the Authors Beth Beth S. Fornauf received areceived B.A. from Villanova and an S. Fornauf a B.A. University, from VillanoM.Ed. from the University of New Hampshire. She recently va University, and an M.Ed. from the University of received her Ph.D. in curriculum and instruction/teacher New Hampshire. She recently received her Ph.D. in education from the University of New Hampshire and is currently curriculum and instruction/teacher education from an assistant professor of special education at Plymouth State the University of New Hampshire and is currently an University. teaching of experience working as both an assistant Her professor special includes education at Plymouth elementary classroom teacher and special educator. In addition, State University. Her teaching experience includes she has worked in educator preparation as a doctoral research working as both an elementary classroom teacher and fellow and instructor. Her research interests include disability special educator. In addition, she has worked in edstudies and Universal Design for Learning within the teacher ucator preparation as a doctoral research fellow and education curriculum. She can be reached by email at: instructor. Her research interests include disability basfornauf@gmail.com. studies and Universal Design for Learning within the teacher education curriculum. She can be reached by email at: basfornauf@gmail.com. Joy Dangora Erickson received her received B.A. and M.S. Joy Dangora Erickson herdegrees B.A. inand education from Purdue University and her Ph.D. in curriculum M.S. degrees in education from Purdue University and (literacy and language concentration) the andinstruction her Ph.D. in curriculum and instructionfrom (literacy University of New Hampshire. Her experience includes working and language concentration) from the University of as an elementary generalist and reading includes specialist for a New Hampshire. Her experience working as combined 11 years. Joy is currently an assistant professor of an elementary generalist and reading specialist for a education at Endicott College. Her research interests include combined 11 years. Joy is currently an assistant proearly childhood reading motivation and engagement, early fessor of education at Endicott College. Her research childhood education for citizenship, and critical literacy. She can interests include early childhood reading motivation be reached by email at: jdangor1@yahoo.com. and engagement, early childhood education for citizenship, and critical literacy. She can be reached by email at: jdangor1@yahoo.com. 196 Fornauf & Erickson; Inclusive Pedagogy Table 1 Articles Exploring UDL in Postsecondary Education, Purpose, and Category, n=38 Publication Ofiesh, Rojas, & Ward (2006) Purpose Category Conceptualizing To present recommendations from the field of universal design as they apply to assessment of students at the postsecondary level Rose, Harbour, Johnston, Daley, To clarify the differences between applying uni- Conceptualizing & Abarbanell (2006) versal design in built vs. learning environment (both the theory and techniques), and to illustrate the principles of UDL Operationalizing Bernachhio, Ross, Washburn, To study process and results of engaging in a Whitney, & Wood (2007) critical friends group that models reflective practice in establishing and maintaining access and inclusion in classes Izzo, Murray, & Novak (2008) The study and development of training materials Operationalizing to improve the quality of postsecondary education for students with disabilities Basham, Lowrey, & deNoyelles To explore an instructional design that used UDL Operationalizing (2010) to proactively plan for computer-mediated communication as a means of student engagement, representation, and expression through reflection on key issues in special education Operationalizing Evans, Williams, King, & Metcalf To provide examples of how they integrate and (2010) model UDL in courses in assessment, classroom management, and instructional planning, and how preservice teachers demonstrate their knowledge of UDL in assignments with students in K-12 settings. Gradel & Edson (2010) To identify beginning strategies and models for Operationalizing implementation of UDL in higher education, while also addressing challenges Morra & Reynolds (2010) To explore how UDL principles and options in- Operationalizing fluence technology-enhanced (hybrid and online) courses Operationalizing Kumar (2011) To describe implementation of a mock conference model of instruction aligned with UDL and learner centered instruction Operationalizing Rao & Tanners (2011) To examine how guidelines of two UD models can be considered during the instructional design process and applied in an online course, and to determine which elements of these models were most valued by and useful to students enrolled in the online course. Schelly, Davies, & Spooner To measure the effectiveness of instructor train- Operationalizing (2011) ing in UDL (as indicated by student perceptions) Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 33(2) 197 Publication Purpose To examine the reflective practice of one faculty member as she applied the UDL framework to her graduate class Davies, Schelly, & Spooner To compare student survey data about an inter(2013) vention group of instructors who received UDL training to student survey data from a control group of instructors who did not receive UDL training. This study features a revised and expanded survey instrument Fovet & Mole (2013) To offer a “methodological snapshot” of an IHE’s process of UDL implementation, and consider the outcomes observed beyond the parameters of disability services (incorporating observations from faculty, administrators and students) Nielson (2013) To analyze the process and complications of incorporating UDL into a first-year composition course to foster independent student identity Schreiner, Rothenberger, & To summarize research in neuroscience, cogniScholtz (2013) tive psychology, and education as related to universal design and to provide ideas for improving college teaching Williams, Rice, Lauren, Morrison, To reimagine both pedagogical and physical Van Winkle, & Elliott (2013) space of the traditional classroom by linking UDL and theories of problem-based learning Beck, Diaz del Castillo, Fovet, To explore the impact of UD implementation for Mole, & Noga (2014) Disability Service providers’ users Black, Weinberg, & Brodwin To determine if faculty were incorporating UDI/ (2014) UDL into their instruction, and faculty attitudes toward students with disabilities Fovet, Jarrett, Mole, & Syncox To highlight how implementation of UDL re(2014) quires increased collaboration among staff, including disability service providers, equity and diversity services, and teaching and learning support Kumar & Wideman (2014) To understand the impact of integrating UDL principles into a postsecondary course Liasidou (2014) To highlight the ways a social justice discourse needs to be incorporated into debates about widening participation in higher education on the grounds of disability. Emphasis on UDL as a vehicle for socially just change in higher education Tobin (2014) To offer strategies to create and convert courses to online format to increase access and engagement Black, Weinberg, & Brodwin To evaluate perspectives of university students (2015) with disabilities on teaching methods that benefited their learning to evaluate whether these align with UDL or UDI Smith (2012) Category Operationalizing Operationalizing Conceptualizing Operationalizing Conceptualizing Conceptualizing Operationalizing Conceptualizing Operationalizing Operationalizing Conceptualizing Operationalizing Conceptualizing 198 Fornauf & Erickson; Inclusive Pedagogy Publication Purpose Heelan, Halligan, & Quirke (2015) Scott, L. A., Temple, P., & Marshall, D. (2015) To provide examples and potential for UDL in Operationalizing health sciences Operationalizing To examine perceptions of special education teachers enrolled in online courses as to whether courses were aligned with UDL principles, and whether the course design improved the teachers’ preparation To describe changes occur in use and knowledge Operationalizing of UDL principles among the faculty who participate in faculty learning communities Operationalizing To examine effectiveness of a biology tutorial available by research librarians, drawing on UDL - for students w disabilities To provide an introduction to some of the specif- Operationalizing ic mental health issues that students may face in a science lab context and to draw on UDL application in the lab to reduce student stress To develop and propose an inclusive and acces- Conceptualizing sible blended teacher education program guided by the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework. To address these pedagogical issues of large lec- Operationalizing ture courses by creating a learning environment that builds on the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles with the goal of providing diverse learners with options in representation, engagement, and expression Conceptualizing To explore whether or not the needs of the students with disabilities, taught within the traditional higher education model, are addressed effectively by the UDL principles. Conceptualizing To determine what is currently being done to prepare educators to implement a UDL framework, the extent to which a UDL framework is being incorporated into preservice courses in higher education, and how a UDL framework is being used to improve postschool outcomes for youth with ID. To present ideas for consideration when design- Operationalizing ing online courses (particularly those in special education) for preservice teachers Operationalizing To extend previous research and explore how experiencing UDL firsthand in a graduate online course might help educators, including in-service general and special education teachers, learn about UDL framework and plan for its practical implementation Hutson & Downs (2015) Webb & Hoover (2015) Miller & Lang (2016) Vininsky & Saxe (2016) Dean, Lee-Post, & Hapke (2017) Griful-Freixenet, Struyven, Verstichele, & Andries (2017) Scott, Thoma, Puglia, Temple, & D’Aguilar (2017) Scott & Temple (2017) Evmenova (2018) Category Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 33(2) 199 Publication Purpose Lohmann, Boothe, Hathcote, & Turpin (2018) Operationalizing To explore the impact of implementing UDL to increase engagement with preservice teachers in online format To explore how UDL may improve teaching and Operationalizing learning in teacher education and to develop a model for implementation in IHEs Operationalizing To explain the history and philosophy of UDL, as well as practical application in building accessibility for all in online courses Moore, Smith, Hollingshead, & Wojcik (2018) Rogers-Shaw, Carr-Chellman, & Choi (2018) Category