Clinical Exp Neuroim - 2023 - Murai - The Japanese clinical guidelines 2022 for myasthenia gravis and Lambert Eaton

Anuncio

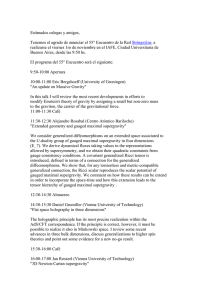

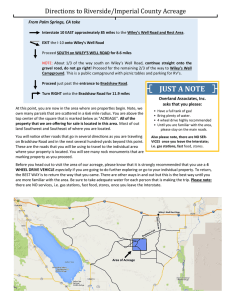

Received: 25 December 2022 Accepted: 25 December 2022 DOI: 10.1111/cen3.12739 INVITED REVIEW The Japanese clinical guidelines 2022 for myasthenia gravis and Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome Hiroyuki Murai 1 Tomihiro Imai 4 Kimiaki Utsugisawa 2 | | Akiyuki Uzawa 5 | | Masakatsu Motomura 3 Shigeaki Suzuki | 6 1 Department of Neurology, School of Medicine, International University of Health and Welfare, Narita, Japan Abstract The revised Japanese clinical guidelines for myasthenia gravis (MG) and Lambert– 2 Department of Neurology, Hanamaki General Hospital, Hanamaki, Japan Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS) were published in 2022. The notable points in 3 these guidelines (GLs) are as follows: (i) these are the first Japanese GLs to include a Faculty of Engineering, Department of Engineering, Medical Engineering Course, Nagasaki Institute of Applied Science, Nagasaki, Japan 4 Department of Neurology, National Hospital Organization Hakone National Hospital, Odawara, Japan 5 Department of Neurology, Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University, Chiba, Japan description of LEMS; (ii) diagnostic criteria of MG are revised to lessen the incidence of false negative patients; (iii) MG is divided into six clinical subtypes; (iv) a high-dose oral steroid regimen with escalation and de-escalation schedule is not recommended by the GLs; (v) the GLs promote the early fast-acting treatment strategy initially proposed in the previous GLs; (vi) refractory MG is defined; (vii) the use of molecular targeted drugs is included; (viii) diagnostic criteria of LEMS are proposed; and 6 Department of Neurology, Keio University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan (ix) treatment algorithms for both MG and LEMS are presented. These new GLs are expected to improve the patients' quality of life and will serve to bridge the present Correspondence Hiroyuki Murai, MD, PhD, Department of Neurology, International University of Health and Welfare, 852 Hatakeda, Narita 286-8520 Japan. Email: murai@iuhw.ac.jp era with the molecular targeted treatment eras. KEYWORDS guidelines, Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome, molecular targeted treatment, myasthenia gravis, refractory, steroids Funding information JSPS KAKENHI, Grant/Award Number: 17K09780; Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Grant/Award Number: 20FC1030 1 | epidemiological survey,5 there are estimated to be approximately I N T RO DU CT I O N 30 000 patients with MG in Japan, with an estimated prevalence rate Myasthenia gravis (MG) is a common neurological autoimmune dis- of 23.1 in 100 000, which has more than doubled from the previous ease. Patients with MG produce autoantibodies targeting molecules in survey held in 2006.6 the receptor The treatment of MG is currently undergoing drastic change. (AChR),1 muscle-specific receptor tyrosine kinase (MuSK)2,3 and low- neuromuscular junctions, including acetylcholine Since the 1970s, and the discovery that MG is an autoimmune dis- density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 4.4 According to a 2018 ease, high doses of oral steroids have been widely used in its treatment. During this era, patients with generalized MG routinely Japanese Committee of Clinical Guidelines for MG consists of the following members present in Appendix. received both thymectomy and high doses of oral steroids, in an escalating and de-escalating manner. Thanks to the use of corticosteroids This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License, which permits use and distribution in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, the use is non-commercial and no modifications or adaptations are made. © 2023 The Authors. Clinical and Experimental Neuroimmunology published by John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd on behalf of Japanese Society for Neuroimmunology. Clin Exp Neuroimmunol. 2023;14:19–27. wileyonlinelibrary.com/journal/cen3 19 MURAI ET AL. TABLE 1 TABLE 2 Diagnostic criteria for myasthenia gravis A. Symptoms Clinical subtypes of MG (O/g-ELTMuN Classification) Ocular (1) Blepharoptosis OMG Generalized AChR‐Ab positive (2) Eye movement disorder g‐EOMG g‐LOMG (3) Facial muscle weakness g‐TAMG (4) Dysarthria AChR‐Ab negative (5) Dysphagia g‐MuSKMG g‐SNMG (6) Mastication disorder (7) Cervical muscle weakness (8) Limb muscle weakness (9) Respiratory disorder Note: These symptoms exhibit easy fatigability and diurnal fluctuations Abbreviations: Ab, antibody; AChR, acetylcholine receptor; g-EOMG, generalized early-onset myasthenia gravis; g-LOMG, generalized lateonset myasthenia gravis; g-MuSKMG, generalized MuSK antibody-positive myasthenia gravis; g-SNMG, generalized seronegative myasthenia gravis; g-TAMG, generalized thymoma-associated MG; MG, myasthenia gravis; OMG, ocular myasthenia gravis. B. Pathogenic autoantibodies (1) Anti-acetylcholine receptor antibody-positive The new clinical GLs were published in May 2022, and include (2) Anti-muscle-specific receptor tyrosine kinase antibody-positive descriptions of clinical guidance for MG and Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS).11 These are the first clinical GLs for LEMS in C. Neuromuscular junction disorders (1) Positive on eyelid easy fatigability test Japan. In the present review article, we introduce the essence of these (2) Positive on ice pack test revised GLs for MG/LEMS. (3) Positive on edrophonium chloride (Tensilon) test (4) Positive on repetitive stimulation test (5) Jitter increase on single fiber electromyography test D. Supportive diagnostic finding 2 | D I A G N O S TI C C R I T E R I A O F M G The diagnostic criteria of MG have been revised (Table 1). The previ- History of improvement by plasmapheresis ous criteria were set along with the previous 2014 clinical GLs, includ- E. Determination ing the description of MuSK antibodies and an eyelid fatigability Definite: Diagnosis of MG made if either of the below is true: test12 or ice pack test12–15 These were added to avoid reporting of 1. One or more items from A is true and any item of B is true. false negative patients. However, even with these descriptions, some 2. One or more items from A is true and any item of C is true and other diseases can be ruled out. patients with MG are not being diagnosed properly. This is because Probable: One or more items from A is true and D is true and other diseases can be ruled out. tests are negative, which can result in patients who are not diagnosed Abbreviation: MG, myasthenia gravis. diagnosing MG is often difficult if both the AChR and MuSK antibody with MG not subsequently receiving correct treatment. Therefore, implementation of plasmapheresis as a therapeutic diagnosis might be considered when other diseases are well differentiated and clinical symptoms strongly suggest MG. Consequently, we attempted to elim- and other immunotherapy, the mortality rate markedly decreased inate “false negative” patients using these new criteria. between 1940 and 2000.7 In the first decade of the 21st century, calcineurin inhibitors, such as tacrolimus and cyclosporine, have been approved as exclusive immunosuppressants in Japan. In addition, 3 | CLINICAL SUBTYPES OF MG intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIg) have been widely used since 2011. The clinical guidelines (GLs) for MG were published in 2014, MG was classified into six clinical subtypes (O/g-ELTMuN Classifica- and proposed new treatment targets and an early fast-acting treat- tion; Table 2). These subtypes emerged from the data of JAMG-R using ment strategy (EFT).8,9 The 2014 GLs largely changed the therapeutic two-step cluster analysis and assessing treatment responses.16,17 This approach to MG in Japan. According to the recent Japan MG Registry classification agrees with the classification proposed by Gilhus study (JAMG-R) 2021, increased EFT introduction resulted in a higher et al.,18,19 with the only difference being that their classification con- 10 percentage of patients achieving their treatment target. sists of seven subtypes, including LRP4-associated MG. LRP4 anti- In 2017, the use of eculizumab was approved in Japan. This was bodies are occasionally detected in other neurological diseases, such as the first molecular-targeted treatment for MG, and it enabled a new amyotrophic lateral sclerosis,20 and the positivity rate among double treatment option for refractory generalized MG. Therefore, a revision seronegative MG markedly differs in each report.21 We considered of the clinical GLs for MG has been due that updates and organizes these facts and concluded that the data are still too immature to regard the treatment options. LRP4-associated MG as an independent phenotype. 17591961, 2023, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/cen3.12739 by Cochrane Mexico, Wiley Online Library on [20/04/2024]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 20 The six subtypes are: (i) ocular MG (OMG); (ii) generalized early- MG symptoms, it often led to long-term administration of mid-level or onset MG (g-EOMG); (iii) generalized late-onset MG (g-LOMG); higher doses of steroids in many patients, and steroid-related adverse (iv) generalized thymoma-associated MG (g-TAMG); (v) generalized reactions and impaired QOL became common.22–24 We hereby MuSK antibody-positive MG (g-MuSKMG); and (vi) generalized declare that a high-dose oral steroid regimen is not recommended any seronegative MG (g-SNMG). OMG includes all forms of ocular MG longer. Given the various treatment options available today, we no regardless of auto-antibody status or thymus histology. g-EOMG is longer must rely on this obsolete strategy. AChR-positive generalized MG without thymoma, whose onset age is Since 2010, the multicenter cross-sectional survey (JAMG-R) has <50 years. g-LOMG is AChR-positive generalized MG without thy- taken place, and has repeatedly obtained detailed clinical informa- moma, whose onset age is ≥50 years. g-TAMG is thymoma-associated tion of patients with MG throughout Japan.10 Notably, many MG that includes all ages. g-MuSKMG is a generalized MG with posi- patients suffer not only impaired QOL because of persistent symp- tive MuSK antibodies. g-SNMG is a generalized MG without AChR or toms or insufficiently reduced oral steroids, but also social disad- MuSK antibodies; LRP4-positive generalized MG is classified in this vantages. Approximately one-third of patients with MG have final group. experienced unemployment or a decrease in income.25 Physicians are often unable to realize patient dissatisfaction with their symptoms and disease state,26 and as complete remission is difficult to 4 | FUNDAMENTAL PHILOSOPHY TO TREAT MG achieve, high QOL-related patient satisfaction should be attained as rapidly as possible. The treatment goal of MG was set to MM-5 mg.24,27 The interna- 4.1 | Recommendations tional consensus guidance defined the treatment goal as “Minimal Manifestation Status or better with no more than grade 1 Common • Full remission is difficult in cases of adult-onset MG, so treatment Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) medication side strategies should consider that treatment might be prolonged, and effects”28 CTCAE grade 1 medication side-effects refer to asymptomatic aim for maintaining health-related quality of life (QOL) and mental or only mild symptoms, and intervention is not indicated. Considering health. that PSL of >5 mg might cause certain symptoms, this treatment goal of • The first goal in MG treatment is minimal manifestations the international consensus guidance is almost equivalent to MM-5 mg. (MM) with oral prednisolone (PSL) of ≤5 mg/day (MM-5 mg), and Refractory MG has been defined in the present GLs. According to treatment strategies should strive to attain this level as rapidly as the data of JAMG-R, refractory MG accounted for 21% of all patients possible. with MG.10 Mantegazza et al. described refractory MG as: (i) failure to • The increase in the rate of patients who achieve the MM-5 mg goal plateaus at 5 years, so rapid treatment is essential. respond adequately to conventional therapies; (ii) inability to reduce immunosuppressive therapy without clinical relapse or a need for • Neither the maximum dose of PSL nor the duration of taking the ongoing rescue therapy, such as IVIg or plasma exchange; (iii) severe mid-level or higher dose of PSL predict the achievement of or intolerable adverse effects from immunosuppressive therapy; MM-5 mg. (iv) comorbid conditions that restrict the use of conventional thera- • Early fast-acting treatment is effective in early achievement of MM-5 mg. • A high-dose oral steroid regimen with an escalation and deescalation schedule is not recommended, because this often results pies; and (v) frequent myasthenic crises even while on therapy.29 The basic concept between these two is similar. Refractory MG should be treated with molecular targeted therapies that are newly developed or under development. in various side-effects and lowered QOL, and does not relate to complete remission or early MM-5 mg. • Refractory MG is a state in which “treatment with multiple oral immunotherapies” or a “combination of oral immunotherapies and 5 | EARLY FAST-ACTING TREATMENT FO R M G repeated fast-acting treatment” are carried out for a certain period that “does not result in sufficient improvement” or in which “con- 5.1 | Recommendations tinuation of treatment is difficult because of side-effects or treatment burden.” • Immunotherapy is always the primary method of treating generalized MG, whereas cholinesterase inhibitors serve a supplementary role. • In the EFT strategy, fast-acting treatment (FT) should be actively carried out to attain both prompt improvement of the symptoms and reduction of steroid dose. • FT incorporates plasmapheresis, IVIg, intravenous methylpredniso- In the 1980s, the main treatment method became administration of high-dose oral steroids (1 mg/kg or 50–60 mg/day), which lone (IVMP) or a combination of these. IVMP should be used skillfully. decreased the prevalence of fatalities as well as improved life expec- • Compared with the conventional treatment depending on oral ste- tancy.7,22 High-dose oral steroids were often administered in an esca- roids, EFT has a higher achievement rate for MM-5 mg, the treat- lating and de-escalating manner. Although this treatment did improve ment goal. 17591961, 2023, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/cen3.12739 by Cochrane Mexico, Wiley Online Library on [20/04/2024]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 21 MURAI ET AL. MURAI ET AL. • During EFT, the oral steroid dose should be kept low from the early stage of the disease and in early combination with the calcineurin treatment. In addition to these side-effects, steroid use itself relates to decreased QOL in patients with MG.24 inhibitor. Therefore, the present GLs do not recommended the use of high- • The case in which frequent FT is required for a long time period dose oral steroids, and the use of ≤5 mg is recommended in ocular MG. In generalized MG, a recommended dose is ≤10 mg and 20 mg at corresponds to refractory MG. the most in severe cases. Non-steroidal immunosuppressants and In generalized MG, FT should be used not only to avoid exacerbation of the symptoms, but also to reduce the medication (mainly oral other immunological treatments are encouraged to suppress the dose of steroids. steroids) or as a maintenance therapy.23,30,31 Were it not for EFT, doses of oral steroids tend to remain high and achievement of MM5 mg becomes difficult. EFT is a treatment strategy whereby low-dose steroids (PSL 7 | NO N - S T E R O I D A L IMMUNOSUPPRESSANTS FOR MG ≤10 mg/day) combined with calcineurin inhibitor are administered from the beginning, and FT is used appropriately thereafter to improve any residual symptoms. 23 7.1 | Recommendations FT incorporates plasmapheresis, IVIg, IVMP or a combination of these. IVMP should be used with caution, because it might cause initial exacerbation. To avoid this condition, it is recommended to administer IVMP just after plasmapheresis or IVIg with reduced dose and reduced days. Methylprednisolone at 500 mg/day for 1 or 2 days is suitable as an initial attempt. Utsugisawa et al. compared the time to first achieve MM-5 mg • The non-steroidal immunosuppressants available in Japan are two kinds of calcineurin inhibitors: cyclosporine and tacrolimus. • Calcineurin inhibitors combined with steroids are expected to improve muscle power and lower steroid doses. • Drug concentration should be checked and attention paid to sideeffects when using calcineurin inhibitors. from 6 to 120 months after starting immunotherapy between EFT and non-EFT patients, and found that achievement of MM-5 mg was Cyclosporine and tacrolimus are the only non-steroidal immuno- more frequent and earlier in the EFT group.30 The recent JAMG-R suppressants available in Japan. Azathioprine was permitted for use in data showed that approximately 40% of all patients with MG received patients with generalized MG in 2022, but is still not commonly used EFT, and those experiencing MM-5 mg increased from 53% in 2015 in Japan. The calcineurin inhibitors, cyclosporine and tacrolimus, have 10 to 65% in 2021. Thus, EFT has been proved to be an exceedingly powerful tool to achieve the treatment goal. both been shown to be effective against MG.33,34 In the early 2000s, calcineurin inhibitors were combined with oral steroid therapy several months after treatment initiation if it was assessed that steroids had been ineffective. It is now recommended that calcineurin inhibitors 6 ORAL STEROIDS FOR MG | should be started soon after the initiation of steroids or simultaneously with steroids. 6.1 | Recommendations • Oral steroids are widely accepted as a standard treatment for MG, although no randomized controlled trial has been completed. • Treatment with oral steroids is generally initiated early in the dis- 8 | INTRAVENOUS METHYLPREDNISOLONE TREATMENT FO R M G ease course and continued over a long period. • There is a responder and poor-responder status to oral steroids. 8.1 | Recommendations • Low-dose oral steroid therapy from the early stage facilitates the achievement of the treatment goal. • High-dose steroid therapy with an escalation and de-escalation schedule requires a long time before taking effect, and adverse reactions due to long-term therapy become a problematic issue. • IVMP is efficacious against generalized MG; however, this must be used with caution and ingenuity, because initial exacerbation might occur. • Intermittent treatment with IVMP improves MG symptoms, while reducing the dose of oral steroids and steroid-related adverse The efficacy of prednisone on MG was first reported in 1970.32 reactions. From then onward, the use of high-dose oral steroids had been a • Initial exacerbation of symptoms caused by IVMP might be miti- mainstream of MG treatment. However, steroids caused various gated by performing the treatment immediately after IVIg or adverse reactions or side-effects, such as susceptibility to infection, plasmapheresis. peptic ulcer, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, femur head necrosis, osteoporosis, psychosis, insomnia, thrombogenesis, cataract, IVMP shows an early reaction and is highly efficacious in treating glaucoma, cushingoid appearance, acne, skin atrophy, erythema and MG, with only mild long-term side-effects.35,36 One drawback is an myopathy. Occasionally, the disadvantages exceed the benefits of the initial exacerbation, but this usually lasts for only 2–5 days. If this 17591961, 2023, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/cen3.12739 by Cochrane Mexico, Wiley Online Library on [20/04/2024]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 22 initial exacerbation is manageable, IVMP is a very simple and effective exacerbation (especially in crises), before thymectomy or when other measure to treat MG, and is frequently used to treat ocular MG.37 treatments are insufficiently effective. One proposed approach to treating generalized MG is an EFT of combined plasmapheresis and IVMP to rapidly improve symptoms.23,30 9 | I N T RA V E N O U S I M M U N O G L O B U LI N TREATMENT FOR MG 9.1 Recommendations | • IVIg is effective for treating moderate-to-serious cases of 11 | M O L E C U L A R T A R G E T E D D R U G (ECULIZUMAB) FOR MG 11.1 | Recommendations MG. Efficacy in mild cases or ocular MG is unclear. • IVIg treatment improves exacerbated MG symptoms at approxi- • Eculizumab is effective against AChR antibody-positive MG and mately the same level of efficacy as plasmapheresis. There is no should be used only when MG symptoms are uncontrollable with evidence of long-term effects. IVIg or plasmapheresis treatment. • The standard therapy regimen is 0.4 g/kg/day for five continuous • Vaccination against Neisseria meningitidis should be carried out days. The speed of infusion should comply with package insert >2 weeks before the initiation of eculizumab, because immunoge- instructions. nicity against this bacteria weakens during eculizumab treatment. • IVIg treatment increases blood viscosity, so dosage quantities and infusion speed should be adjusted appropriately based on the over- Eculizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that binds to all condition of the patient if concomitant cardiovascular or cere- human terminal complement protein C5. This inhibits cleavage of C5 brovascular conditions are present. to C5a and C5b, and prevents formation of the membrane attack • IVIg treatment is more useful than plasmapheresis for elderly patients or patients with unstable circulatory dynamics. • IVIg can be administered in outpatient clinics. complex. Eculizumab was first approved for treating paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria and then for treating atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Eculizumab is now approved for generalized MG and neuromyelitis optica therapy. IVIg treatment is widely used for autoimmune neuromuscular dis- The REGAIN study showed the efficacy of eculizumab treatment eases. Many details of the mechanism of action of IVIg against MG on generalized MG.39 The MG activities of daily living score reduced remain unknown, but it is hypothesized to be caused by inhibition by 4.7 points in the eculizumab group and 2.8 points in the placebo of the complement cascade and competition with autoantibodies group. Long-term efficacy and safety were shown in REGAIN and its in the postsynaptic membrane of the neuromuscular junction. 38 open label extension study.40 Improvements in clinical symptoms Compared with plasmapheresis, IVIg therapy requires less special were maintained through 3 year-treatment and there were no cases expertise and experience on the part of the practitioner and offers of meningococcal infection. Eculizumab is ineffective for patients with greater safety, as this does not entail transient post-therapy rare C5 mutations, which accounts for 3.5% of the Japanese exacerbation. population.41 10 12 | T H YM E C TOM Y F O R NON-THYMOMATOUS MG PLASMAPHERESIS FOR MG | 10.1 | Recommendations 12.1 | Recommendations • Plasmapheresis is effective for treating MG. • As long-term efficacy of plasmapheresis treatment is not proven, it should be combined with immunotherapy, such as IVMP. • Simple plasma exchange, double filtration plasmapheresis and immunoadsorption plasmapheresis can all be carried out against MG, and all have equivalent effects. • Plasma exchange is recommended for treating anti-MuSK • Thymectomies might be effective and could be considered for non-thymomatous patients with early onset MG (onset <50 years years) in cases that show positive AChR antibodies and thymic hyperplasia in the early stages of the disease. • Thymectomy is not considered first-line treatment for nonthymomatous LOMG. antibody-positive MG. Until publication of the MGTX study in 2016 and 2019,42,43 there Plasmapheresis is carried out to temporarily improve clinical had been no precise analysis of thymectomy outcomes for non- symptoms by removing causative substances, such as AChR and thymomatous MG. The MGTX study reported that the Quantitative MuSK antibodies, from the circulating plasma. Plasmapheresis is indi- MG score was lower in the thymectomy + steroid group than that in cated for MG when symptoms become worse, during acute the steroid-only group (6.15 vs 8.99, respectively, over the 3-year 17591961, 2023, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/cen3.12739 by Cochrane Mexico, Wiley Online Library on [20/04/2024]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 23 MURAI ET AL. MURAI ET AL. F I G U R E 1 Treatment algorithm for myasthenia gravis. AChEI, acetylcholinesterase inhibitor; CNI, calcineurin inhibitor; EFT, early fast-acting treatment; FT, fast-acting treatment; g-EOMG, generalized early-onset myasthenia gravis; g-LOMG, generalized late-onset myasthenia gravis; gMuSKMG, generalized MuSK antibody-positive myasthenia gravis; g-SNMG, generalized seronegative myasthenia gravis; g-TAMG, generalized thymoma-associated myasthenia gravis; IAPP, immunoadsorption plasmapheresis; IVIg, intravenous immunoglobulin; IVMP, intravenous methylprednisolone; OMG, ocular myasthenia gravis; PLEX, plasma exchange; PSL, prednisolone observation period).42 The Quantitative MG score reduction was 2.84 points. The MGTX study was the first ever evidence-rich research cover- TABLE 3 syndrome Diagnostic criteria for Lambert–Eaton myasthenic A. Symptoms ing thymectomy for non-thymomatous MG, and it proved the efficacy (1) Weakness of proximal extremities of thymectomy on patients with EOMG. However, it also proved that (2) Decreased tendon reflexes the effect is modest and that the surgery could not bring patients to remission. Given the various treatment options available recently, this level of reduction might be achieved with EFTs and several of the (3) Autonomic symptoms B. Abnormalities on repetitive stimulation test drugs that target newly identified mechanisms. Therefore, thymec- (1) Decreased amplitude of initial compound muscle action potential tomy should be considered as one of the options for patients with (2) Decrement ≥10% at low frequency (2 5 Hz) non-thymomatous MG. (3) Increment ≥60% after maximum voluntary contraction for 10 s or at high frequency (20 50 Hz) C. Pathogenic autoantibodies 13 | T RE A T M E N T A L G O R I T H M F O R M G In the present GLs, a treatment algorithm was proposed according to the six clinical subtypes (Figure 1). In OMG, cholinesterase inhibitor and topical naphazoline eye drops are initially used, and can be followed by a low dose of PSL if necessary. PSL should be administered at a dose of ≤5 mg/day. Thymectomy should be carried out if thymoma exists. If these treatments are insufficient, IVMP should be carried out and repeated as required. Calcineurin inhibitors could be added to the treatment. P/Q-type voltage-gated calcium channel (P/Q-type VGCC) antibody D. Determination Diagnosis of LEMS made if either of the below is true: 1. Two or more items including (1) from A are true and all three items of B are true. 2. Two or more items including (1) from A are true and two or more items including (3) from B are true and C is positive Abbreviations: LEMS, Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome; P/Q-type VGCC, P/Q-type voltage-gated calcium channel. In generalized MG, the treatment should be started with a low dose of PSL with calcineurin inhibitor and cholinesterase inhibitor. Generally, the PSL dose should be kept to <10 mg/day and should not produce insufficient results, EFT should be introduced. FT is repeated exceed 20 mg/day. Thymectomy is mandatory for g-TAMG, but until MM-5 mg is achieved. If FT is required frequently, such as three optional for g-EOMG. There is no indication of thymectomy for times or more per year, the case is certified as refractory and the use g-LOMG, g-MuSKMG or g-SNMG. If the aforementioned treatments of molecular targeted drugs is taken into consideration. 17591961, 2023, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/cen3.12739 by Cochrane Mexico, Wiley Online Library on [20/04/2024]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 24 F I G U R E 2 Treatment algorithm for Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS). 3,4-DAP, 3,4-diaminopyridine; AZA, azathioprine; IVIg, intravenous immunoglobulin; PLEX, plasma exchange; PSL, prednisolone; SCLC, small cell lung cancer 14 | DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA OF LEMS completed to detect small cell lung cancer. Even if the result is negative, these examinations should be repeated every 3–6 months for at These are the first GLs for LEMS, and the diagnostic criteria of LEMS least 2 years.46 are proposed herein (Table 3). The measurement of P/Q-type voltage- If muscle weakness is severe, immunotherapy should be carried gated calcium channel antibody levels is now commercially available out based on treating MG. IVIg and plasmapheresis are selected in the in Japan. However, measuring these antibody levels is not mandatory acute phase, and steroids and immunosuppressants are used for long- in diagnosing LEMS, and electrophysiology surpasses immunological term treatment. However, as these treatments are not approved in findings in LEMS diagnosis. Japan, they remain off label. LEMS is a paraneoplastic neurological syndrome in which a malignant tumor, mostly small-cell lung cancer, is present in >50% of cases. In >90% of LEMS patients, antibodies against P/Q-type voltage-gated 16 | C O N CL U S I O N S calcium channel, which are located at nerve terminals, are detected. The prevalence of LEMS in Japan was estimated to be 0.27 per Eight years have passed since the previous clinical GLs were pub- 100 000.44 Core symptoms of LEMS are weakness of proximal extremi- lished. The 2014 GLs set the patient QOL as a central issue and ties, decreased tendon reflexes and autonomic symptoms. Cases sought to ensure this was nourished as much as possible. This spirit accompanied by small cell lung cancer have more severe muscle weak- has been maintained with the 2022 GLs. The treatment scene of MG ness. Differential diagnosis of LEMS should be given even in patients is drastically changing, with many novel molecular targeted drugs on with mild weakness or cerebellar ataxia because of a condition called trial. It is expected that the new GLs will value the QOL of patients “paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration with LEMS.” Recently, along and will connect the present treatment regimens to the developing with the increased use of immune checkpoint inhibitors, LEMS cases molecular targeted treatment era. have been drawing attention as immune-related adverse events. ACKNOWLEDG MENTS This review includes a study supported (in part) by a Health and 15 | TREATMENT ALGORITHM FOR LEMS Labor Sciences Research Grant on Rare and Intractable Diseases (Validation of Evidence-based Diagnosis and Guidelines, and Figure 2 shows the treatment algorithm for LEMS.45 Although the Impact on Quality of Life in Patients with Neuroimmunological algorithm indicates that treating commences with 3,4-diaminopyridine Diseases) from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan (3,4-DAP), it is not yet available in Japan. A clinical trial is now in pro- (Grant number: 20FC1030), and by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant number: gress. Once LEMS diagnosis has been made, vigorous examinations, 17K09780). We thank Mike Herbert, PhD, from Edanz Group such as computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, tumor (https://en-author-services.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of marker expression, and positron emission tomography, should be this manuscript. 17591961, 2023, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/cen3.12739 by Cochrane Mexico, Wiley Online Library on [20/04/2024]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 25 MURAI ET AL. MURAI ET AL. CONF LICT OF IN TE RE ST H. Murai has served as a consultant for Alexion, argenx, UCB and Roche, and has received speaker honoraria from the Japan Blood Products Organization and Chugai Pharmaceutical, and research support from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan. H. Murai is Editor-in-Chief of Clinical and Experimental Neuroimmunology. K. Utsugisawa has served as a paid consultant for UCB Pharma, argenx, Janssen Pharma, Viela Bio, Chugai Pharma, Hanall BioPharma and Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, and has received speaker honoraria from argenx, Alexion Pharmaceuticals and the Japan Blood Products Organization. M. Motomura has served as a consultant for Alexion, argenx, UCB and Dydo, and received research support from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan. A. Uzawa has received honoraria from Alexion Pharmaceuticals and argenx. S. Suzuki received personal fees from Alexion Pharmaceuticals, the Japan Blood Products Organization and Asahi Kasei Medical. T. Imai has no conflict of interest to declare. DIS CLOSUR ES OF E THICAL STATEMENTS Approval of the research protocol: N/A. Informed Consent: N/A. Registry and the Registration No. of the study/trial: N/A. Animal Studies: N/A. ORCID Hiroyuki Murai https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1612-1440 RE FE R ENC E S 1. Drachman DB. Myasthenia gravis. N Engl J Med. 1994;330: 1797–810. 2. Hoch W, McConville J, Helms S, Newsom-Davis J, Melms A, Vincent A. Auto-antibodies to the receptor tyrosine kinase MuSK in patients with myasthenia gravis without acetylcholine receptor antibodies. Nat Med. 2001;7:365–8. 3. Shiraishi H, Motomura M, Yoshimura T, Fukudome T, Fukuda T, Nakao Y, et al. Acetylcholine receptors loss and postsynaptic damage in MuSK antibody-positive myasthenia gravis. Ann Neurol. 2005;57: 289–93. 4. Higuchi O, Hamuro J, Motomura M, Yamanashi Y. Autoantibodies to low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 4 in myasthenia gravis. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:418–22. 5. Yoshikawa H, Adachi Y, Nakamura Y, Kuriyama N, Murai H, Nomura Y, et al. Two-step nationwide epidemiological survey of myasthenia gravis in Japan 2018. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0274161. 6. Murai H, Yamashita N, Watanabe M, Nomura Y, Motomura M, Yoshikawa H, et al. Characteristics of myasthenia gravis according to onset-age: Japanese nationwide survey. J Neurol Sci. 2011;305:97–102. 7. Grob D, Brunner N, Namba T, Pagala M. Lifetime course of myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve. 2008;37:141–9. 8. Murai H. Japanese clinical guidelines for myasthenia gravis: putting into practice. Clin Exp Neuroimmunol. 2015;6:21–31. 9. Japanese Committee of Clinical Guidelines for MG. Japanese clinical guidelines 2014 for MG [In Japanese]. Nankodo, Tokyo; 2014. 10. Suzuki S, Masuda M, Uzawa A, et al. Japan MG registry: chronological surveys over 10 years. Clin Exp Neuroimmunol. 2023;14:5–12. 11. Japanese Committee of Clinical Guidelines for MG/LEMS. Japanese clinical guidelines 2022 for MG and LEMS [In Japanese]. Nankodo, Tokyo; 2022. 12. Mittal MK, Barohn RJ, Pasnoor M, McVey A, Herbelin L, Whittaker T, et al. Ocular myasthenia gravis in an academic neuro-ophthalmology clinic: clinical features and therapeutic response. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis. 2011;13:46–52. 13. Golnik KC, Pena R, Lee AG, Eggenberger ER. An ice test for the diagnosis of myasthenia gravis. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:1282–6. 14. Jacobson DM. The "ice pack test" for diagnosing myasthenia gravis. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:622–3. 15. Chatzistefanou KI, Kouris T, Iliakis E, Piaditis G, Tagaris G, Katsikeris N, et al. The ice pack test in the differential diagnosis of myasthenic diplopia. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:2236–43. 16. Akaishi T, Suzuki Y, Imai T, Tsuda E, Minami N, Nagane Y, et al. Response to treatment of myasthenia gravis according to clinical subtype. BMC Neurol. 2016;16:225. 17. Akaishi T, Yamaguchi T, Suzuki Y, Nagane Y, Suzuki S, Murai H, et al. Insights into the classification of myasthenia gravis. PLoS One. 2014; 9:e106757. 18. Gilhus NE, Verschuuren JJ. Myasthenia gravis: subgroup classification and therapeutic strategies. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:1023–36. 19. Gilhus NE, Skeie GO, Romi F, Lazaridis K, Zisimopoulou P, Tzartos S. Myasthenia gravis - autoantibody characteristics and their implications for therapy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12:259–68. 20. Tzartos JS, Zisimopoulou P, Rentzos M, Karandreas N, Zouvelou V, Evangelakou P, et al. LRP4 antibodies in serum and CSF from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2014;1:80–7. 21. Bacchi S, Kramer P, Chalk C. Autoantibodies to low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 4 in double seronegative myasthenia gravis: a systematic review. Can J Neurol Sci. 2018;45:62–7. 22. Gilhus NE. Autoimmune myasthenia gravis. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9:351–8. 23. Nagane Y, Suzuki S, Suzuki N, Utsugisawa K. Early aggressive treatment strategy against myasthenia gravis. Eur Neurol. 2011;65:16–22. 24. Masuda M, Utsugisawa K, Suzuki S, Nagane Y, Kabasawa C, Suzuki Y, et al. The MG-QOL15 Japanese version: validation and associations with clinical factors. Muscle Nerve. 2012;46:166–73. 25. Nagane Y, Murai H, Imai T, Yamamoto D, Tsuda E, Minami N, et al. Social disadvantages associated with myasthenia gravis and its treatment: a multicentre cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2017;7: e013278. 26. Burns TM. History of outcome measures for myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve. 2010;42:5–13. 27. Utsugisawa K, Suzuki S, Nagane Y, Masuda M, Murai H, Imai T, et al. Health-related quality of life and treatment targets in myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve. 2014;50:493–500. 28. Sanders DB, Wolfe GI, Benatar M, Evoli A, Gilhus NE, Illa I, et al. International consensus guidance for management of myasthenia gravis: executive summary. Neurology. 2016;87:419–25. 29. Mantegazza R, Antozzi C. When myasthenia gravis is deemed refractory: clinical signposts and treatment strategies. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2018;11:1756285617749134. 30. Utsugisawa K, Nagane Y, Akaishi T, Suzuki Y, Imai T, Tsuda E, et al. Early fast-acting treatment strategy against generalized myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve. 2017;55:794–801. 31. Murai H, Utsugisawa K, Nagane Y, Suzuki S, Imai T, Motomura M. Rationale for the clinical guidelines for myasthenia gravis in Japan. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2018;1413:35–40. 32. Warmolts JR, Engel WK, Whitaker JN. Alternate-dy prednisone in a patient with myasthenia gravis. Lancet. 1970;2:1198–9. 33. Yoshikawa H, Kiuchi T, Saida T, Takamori M. Randomised, doubleblind, placebo-controlled study of tacrolimus in myasthenia gravis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82:970–7. 34. Tindall RS, Rollins JA, Phillips JT, Greenlee RG, Wells L, Belendiuk G. Preliminary results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of cyclosporine in myasthenia gravis. N Engl J Med. 1987;316: 719–24. 17591961, 2023, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/cen3.12739 by Cochrane Mexico, Wiley Online Library on [20/04/2024]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 26 35. Lindberg C, Andersen O, Lefvert AK. Treatment of myasthenia gravis with methylprednisolone pulse: a double blind study. Acta Neurol Scand. 1998;97:370–3. 36. Schneider-Gold C, Gajdos P, Toyka KV, Hohlfeld RR. Corticosteroids for myasthenia gravis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;2005:Cd002828. 37. Ozawa Y, Uzawa A, Kanai T, Oda F, Yasuda M, Kawaguchi N, et al. Efficacy of high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone therapy for ocular myasthenia gravis. J Neurol Sci. 2019;402:12–5. 38. Dalakas MC. Intravenous immunoglobulin in autoimmune neuromuscular diseases. JAMA. 2004;291:2367–75. 39. Howard JF Jr, Utsugisawa K, Benatar M, Murai H, Barohn RJ, Illa I, et al. Safety and efficacy of eculizumab in anti-acetylcholine receptor antibody-positive refractory generalised myasthenia gravis (REGAIN): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre study. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16:976–86. 40. Muppidi S, Utsugisawa K, Benatar M, Utsugisawa K, Benatar M, Murai H, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of eculizumab in generalized myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve. 2019;60:14–24. 41. Nishimura J, Yamamoto M, Hayashi S, Ohyashiki K, Ando K, Brodsky AL, et al. Genetic variants in C5 and poor response to eculizumab. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:632–9. 42. Wolfe GI, Kaminski HJ, Aban IB, Minisman G, Kuo HC, Marx A, et al. Randomized trial of thymectomy in myasthenia gravis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:511–22. 43. Wolfe GI, Kaminski HJ, Aban IB, Minisman G, Kuo HC, Marx A, et al. Long-term effect of thymectomy plus prednisone versus prednisone alone in patients with non-thymomatous myasthenia gravis: 2-year extension of the MGTX randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18:259–68. 44. Yoshikawa H, Adachi Y, Nakamura Y, Kuriyama N, Murai H, Nomura Y, et al. Nationwide survey of Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome in Japan. BMJ Neurology Open. 2022;4:e000291. 45. Kitanosono H, Shiraishi H, Motomura M. P/Q type calcium channel antibody and Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome [in Japanese]. Brain Nerve. 2018;70:341–55. 46. Titulaer MJ, Lang B, Verschuuren JJ. Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome: from clinical characteristics to therapeutic strategies. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:1098–107. How to cite this article: Murai H, Utsugisawa K, Motomura M, Imai T, Uzawa A, Suzuki S. The Japanese clinical guidelines 2022 for myasthenia gravis and Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome. Clin Exp Neuroimmunol. 2023;14(1):19–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/cen3.12739 APPENDIX A Japanese Committee of Clinical Guidelines for MG consists of the following members. Chairperson: Hiroyuki Murai; Co-chairperson: Kimiaki Utsugisawa, Masakatsu Motomura; Committee members: Keiko Ishigaki, Tomihiro Imai, Akiyuki Uzawa, Meinoshin Okumura, Naoki Kawaguchi, Shingo Konno, Shigeaki Suzuki, Yasushi Suzuki, Masanori Takahashi, Shunya Nakane, Yoshiko Nomura, Naoya Minami, Hiroaki Yoshikawa; Collaborators: Takashi Irioka, Kazuo Iwasa, Makoto Samukawa, Hirokazu Shiraishi, Yuriko Nagane, Ichiro Yabe, Daisuke Yamamoto; Systematic reviewers: Tetsuya Kanai, Takashi Kanzaki, Tomoya Kubota, Takatoshi Sato, Keiko Toyooka; Member from outside the committee: Takeo Nakayama; Advisors: Akio Suzumura, Masaharu Takamori. The authors wrote this review on behalf of all the members. 17591961, 2023, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/cen3.12739 by Cochrane Mexico, Wiley Online Library on [20/04/2024]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 27 MURAI ET AL.