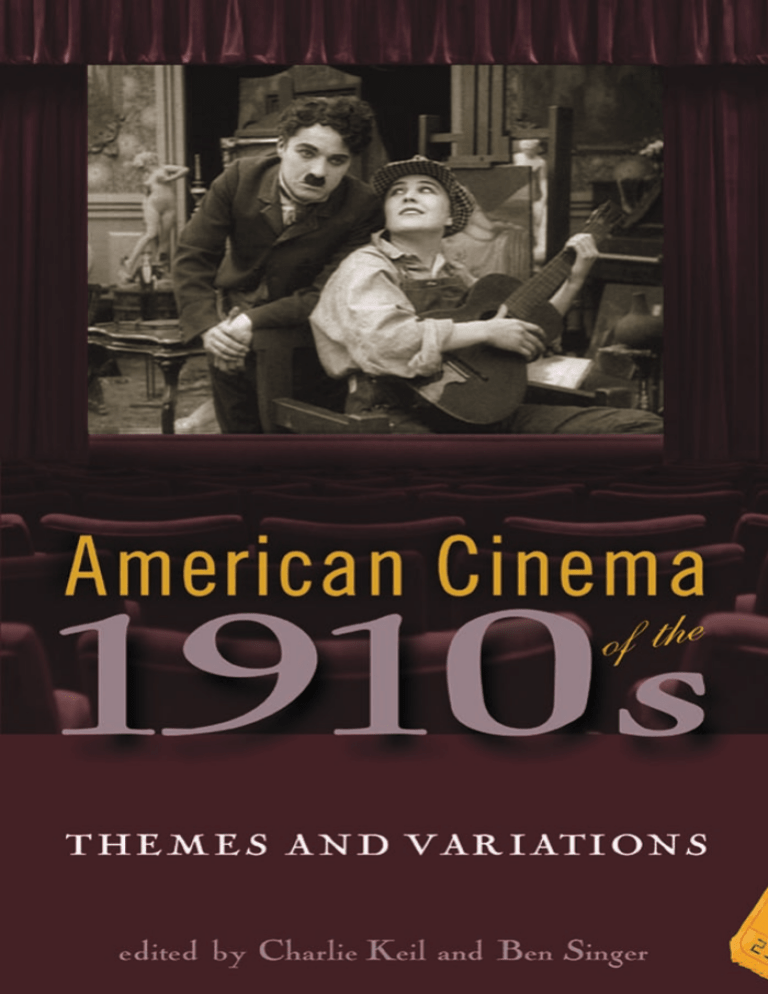

American Cinema Of The 1910s Themes And Variations The Screen Decades Series

Anuncio