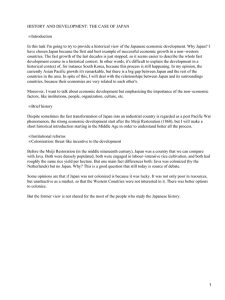

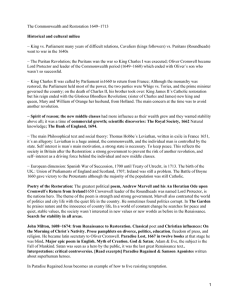

TECHNICAL ARTICLE Ecological restoration-based education in the Colombian Amazon: toward a new society–nature relationship Natasha V. Garzón1, Carlos H. Rodríguez León2, Eliane Ceccon3 , Daniel R. Pérez4,5 Caquetá Department, in the Colombian Amazon, has a historical context of deforestation, education of poor quality, land tenure conflicts, and social violence. Thus, there is an urgent need to restore not only the ecosystem, but also the social fabric and the society–nature relationship. This article describes the process, impacts, obstacles, and lessons learned from a program of ecological restoration-based education for local communities. During 2017, a group of 15 local people were selected and trained in ecological restoration to become, as we called them, “local scientists” (LS). After this educative process, these LS, together with researchers from social sciences and biology, developed an ecological restoration education program aimed to local peasants. The bioregional current of environmental education and significant learning theory were the educative theoretical frameworks used. The pedagogical contents were grouped into five main themes: (1) soils, (2) farm planning, (3) river basins, (4) monitoring, and (5) social organization. During 2018, between 8 and 70 peasants per community participated in the program. The last phase, carried out in 2019, consisted of the propagation of native forest species and outplantings by the program participants, to restore the landscape connectivity in a region considered to be high priority. Peasants built 71 nursery gardens on their farms with their own labor. They produced 400,000 seedlings of 21 native forest species, which were further planted on 277 farms over 550 ha. The implications of the pedagogical process of the program, the advances in restoration of degraded forests, and changes in society–nature relationships are discussed. Key words: Caquetá, environmental education, non-formal education, participative process, significant learning theory, United Nations Decade on Ecosystem Restoration Implications for Practice • Ecological restoration can be a pathway toward ecologi- cal literacy and teaching people to reinhabit their territories, even when affected by social conflicts. • Upon receiving an appropriate educational program, local groups of peasants can be empowered and become restoration knowledge multipliers. • The use of different educational tools and activities can facilitate the assimilation of new ideas and promote environmental paradigm shifts. Introduction Colombia is one of the most biodiverse countries in the world (Gonzalez-Salazar et al. 2017). However, much of this biodiversity is being lost by the extensive deforestation and habitat fragmentation mainly due to agricultural expansion, cattle raising, and illegal crops (Etter et al. 2006; Armenteras et al. 2011; Aguilar et al. 2015; Gonzalez-Salazar et al. 2017; Clerici et al. 2018). The Caquetá Department, with an area of 8,896,500 ha, is the third largest department of Colombia, and it shows the highest rate of deforestation, around 52,563 ha/year between 2000 and 2017 (IDEAM 2018). Deforestation in Caquetá began under the socioeconomic models developed during the process of colonization (Niño September 2020 Restoration Ecology Vol. 28, No. 5, pp. 1053–1060 Arcila et al. 2000). In this region, there have been three main stages of human settlement: indigenous occupation for 22,000 years or more, agrarian colonization since 1900, and new colonization and urbanization since 1950 (Niño Arcila et al. 2000). Prehispanic indigenous culture had a relationship with nature that was not defined by dependence on extractive production models for economic markets. However, the agrarian colonization by the Spanish people changed this model toward a strong utilitarian conception of nature, and led to a Author contributions: NVG, CHRL coordinated field applications; DRP, EC wrote and edited the manuscript. 1 Natasha Valentina Garzón, Instituto Amazónico de Investigaciones Científicas SINCHI, CP 180001, Florencia, Caquetá, Colombia 2 Carlos Hernando Rodríguez León, Instituto Amazónico de Investigaciones Científicas SINCHI, CP 180001, Florencia, Caquetá, Colombia 3 Eliane Ceccon, Centro de Investigaciones Multidisciplinarias, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Av. Universidad Circuito II s/n, Col. Chamilpa CP 62210, Cuernavaca, Morelos, Mexico 4 Laboratory of Rehabilitation and Ecological Restoration of Arid and Semiarid Ecosystems (LARREA), National University of Comahue, CP 8300 Neuquén, Argentina 5 Address correspondence to D. R. Pérez, email danielrneuquen@gmail.com © 2020 Society for Ecological Restoration doi: 10.1111/rec.13216 Supporting information at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/rec.13216/suppinfo 1053 period of massive deforestation and the introduction of livestock, distorting the sustainability of the territory. After 1950, with the increase of global and local demand, there were new waves of timber extraction and deforestation for meat and milk production (Niño Arcila et al. 2000). Later, Caquetá became one of the epicenters of conflicts among armed groups known as “guerrillas” and disputes over illegal coca crops added to existing conflicts (Murcia et al. 2013; Clerici et al. 2018). In this complex socioecological context, at present there is an urgent need to restore not only the degraded ecosystems, but also the social fabric and the relationship between society and nature. Like several other places in Latin America and the Caribbean, Caquetá currently has a high density of rural population living in biodiversity hotspots in need of ecological restoration (Aguilar et al. 2015), and in many regions without basic access to education programs (UNESCO 2013). In tropical regions, Janzen (1988) was one of the first to point out the need to generate links between restoration and education: “It is critical that diverse and imaginative education programs be taught within the restoring of wild land, and local people be intellectually involved in the restoration and management process […].” However, in most cases, formal education is not accessible to local communities in tropical regions. Even when formal education does exist, programs or curricula are frequently not connected to the regional socioecological context, teachers do not usually have adequate training for rural contexts, and educative materials are no contextualized (UNESCO 2013; Pérez et al. 2017). Across Latin America, several institutions have joined efforts to develop social, institutional, or organizational skills to influence public policies and decision-makers, generate international networks, and help people develop “soft” skills, such as leadership, project management, or entrepreneurship (Bloomfield et al. 2018; Meli et al. 2019). However, greater efforts are required to effectively meet the educational demands of rural communities of this region. For this reason, it is valuable that the strategy of the United Nations Decade on Ecosystem Restoration 2021–2031 (UN 2020) has included, as a goal, the generation of diverse ways of children and adult education in benefits of ecological restoration. The document literally claims that: “It is critical that diverse and imaginative education programs be taught within the restoring of wild land, and local people be intellectually involved in the restoration and management process […].” Ecological restoration-based education is considered a fundamental tool for the success of restoration in the long term and in the reestablishment of the relationship between society and nature (McCann 2011; Pérez et al. 2019). In this study, we describe a program of ecological restoration-based education for local communities implemented in Caquetá Department in 2017–2019, to contribute to the process of social and ecological restoration after the historical degradation of the tropical forests (SINCHI 2013). The goals of the project were: (1) to provide opportunities to share knowledge about ecology, biodiversity, and restoration among local peasants and researchers; (2) to contribute to peasants’ active participation in ecological restoration based on theoretical and practical knowledge; and (3) to install and maintain restoration plots on farms in the region. We present 1054 the methodologies used to achieve the above-mentioned objectives and discuss their scope over the 2 years of their implementation. Methods Study Area The project is located in Caquetá Department, in the AndeanAmazon piedmont of Colombia, specifically in the municipalities of Florencia, Morelia, Belén de los Andaquíes, and San José de Fragua, between 1 210 –1 480 N and 75 300 –76 040 W (Fig. 1). According to the Köppen (1936) classification, the climate is equatorial superhumid (Afi), with an average annual rainfall of 3,235 mm and an average temperature of 25.1 C (Murad & Pearse 2018). There are three main units in the landscape: mountains, rolling hills (hereafter “lomerío”), and floodplains, considered of high priority for restoration (Fig. 1). The current predominant land use is cattle grazing. Cattle feed mainly on exotic grasses (Brachiaria spp.), but as the soils are nutrient-poor, there is a progressive reduction of grass productivity, resulting in decreasing livestock yields over time (Becerra-Ordoñez et al. 2014). Education Theoretical Framework Ecological restoration-based education (hereafter RBE) refers to ecological restoration efforts that are intentionally designed to include an educational purpose. Like ecological restoration, RBE is a process that occurs over a lifetime and includes both ecological and social components (McCann 2011; Pérez et al. 2019). The educational format (social and institutional context in which the educational process is implemented) was “non-formal education” for adults (Pérez et al. 2019). The selection of educational contents was based on the current of environmental education (EE) defined as “bioregionalism” (Sauvé 2005). This current proposes the development of contents with the main goal of reconnecting regional nature with local cultures, allowing residents to reinhabit environments (McGinnis 2005) and promoting a sense of belonging and relationship with a place (Hensley 2013). This EE perspective is also known as “pedagogy of place” or “place-based environmental education” (Orr 1992). The teaching-learning framework used in the project was “significant learning” (Ausubel et al. 1978). From this educative conception, the simple presentation of facts or concepts is not enough to generate learning. Rather, education requires problematic situations, potentially significant educational materials, and intrinsic motivation (Valerio 2012). This may allow the restructuring of intuitive theories based on everyday experience (Vosniadou 2007). In this context, the educative activities were planned to promote: (1) critical thinking (students analyze and evaluate), (2) creative thinking (students imagine and create), and (3) practical thinking (students solve problems and make decisions) (Fink 2003). The design of the “significant learning” program followed the Fink (2003) proposal, which has the advantage of being easy to Restoration Ecology September 2020 1526100x, 2020, 5, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/rec.13216 by Universidad Nacional Colombia, Wiley Online Library on [14/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License Restoration and education in Colombian Amazon Figure 1 Location of Caquetá Department in Colombia. Areas with different levels of ecological restoration priority, determined by previous studies of SINCHI Institute are indicated with different colors. Credit: SINCHI Institute. replicate step by step (Supplement S1). Fink’s proposal pays attention to “situational factors”—the specific contexts of teaching/learning, nature of the subject, and characteristics of the learners and the teachers. These situational factors are fundamental in educative planning, because effective communication is critical for significant learning. In fact, the educative process requires the generation of shared meanings and the acquisition of new knowledge constructed from the needs, aspirations, and motivations of the participants. Particularly, as we work with adult peasants, who have extensive experience and knowledge, it is important to achieve a dialogue that allows them to question and criticize culturally inherited rationalities that cause environmental degradation (Leff 2010). Figure 2 Scheme of implementation sequence of ecological restoration-based education program and general organization of the educative process (vertical line). In the lower line of blocks some principal goals are noted. September 2020 Restoration Ecology 1055 1526100x, 2020, 5, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/rec.13216 by Universidad Nacional Colombia, Wiley Online Library on [14/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License Restoration and education in Colombian Amazon Table 1 Basic contents of pedagogical materials used in the ecological restoration-based education program and first page of each unit. First Page of the Pedagogical Material Pedagogical Unit Contents The socioecological importance of soil. Soil as a living system, formation and ecological functions, dynamics of degradation, soil conservation and restoration. Ecological restoration as tool for farm planning. Farms as a unit of planning, incentives and motivations, for decisions, implications for the landscape, ecosystems and restoration. How do we restore our river basins? Characteristics, composition, and ecological functions of riparian forests in Caquetá, flood and rainfall pulses, riparian floristic communities, ecological services. Participatory monitoring. Citizen science, decision-making, restoration objectives and goals, variables, indicators, information capture. Social organization and community strengthening. The meaning of community, typology of social organizations, community participation in restoration ecology projects, common goods. For this reason, the strategy was for a group of local people to act as the mediators of the educative process, or education multipliers. Here, we refer to these people as “local scientists” (hereafter, LS). The LS were local people with technical experience in rural activities and peasants with deep understanding of the local environmental and productive problems. The selection of LS was made by the SINCHI Institute staff, based on snowball sampling (Naderifar et al. 2017). This qualitative methodology consists in the selection of a first person with the desired profile, 1056 who offers a new contact during an interview. Following each new interview, a new participant is integrated until completing the desired total number. A team of 15 LS was assembled, with the goal of educational continuity over the time. The educative process was called the “school of local scientists” (hereafter, SLS). The role of LS in the conceptual structure of the project is illustrated in Figure 2. In the context of SLS, the education program was organized by the LS, SINCHI researchers, and pedagogy specialists, who defined and produced the educational Restoration Ecology September 2020 1526100x, 2020, 5, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/rec.13216 by Universidad Nacional Colombia, Wiley Online Library on [14/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License Restoration and education in Colombian Amazon Table 2 Species produced in nursery gardens of the ecological restoration-based education program, classified by tree species and topography in which it is found. Topography = rolling hills or “lomerío” (L), mountain (M), floodplain (F). Topography Scientific Name Common Name (Spanish) L M F Cedrelinga cateniformis (Ducke) Ducke Minquartia guianensis Aubl. Clarisia racemosa Ruiz & Pav. Myrcia splendens (Sw.) DC. Euterpe precatoria Mart. Guarea grandiflora Decne. ex Steud. Piptocoma discolor (Kunth) Pruski Zygia longifolia (Humb. & Bonpl. ex Willd.) Britton & Rose Aspidosperma spruceanum Benth. ex Müll. Arg. Eschweilera coriacea (DC.) S.A. Mori Brosimum rubescens Taub. Inga nobilis Willd. Parkia multijuga Benth. Lacmellea speciosa Woodson Vismia baccifera (L.) Triana & Planch. Simarouba amara Aubl. Trichanthera gigantea (Bonpl.) Nees Iriartea deltoidea Ruiz & Pav. Socratea exorrhiza (Mart.) H. Wendl. Oenocarpus bataua Mart. Couma macrocarpa Barb. Rodr. Achapo Ahumado Arracacho Arrayán Asaí Bilibil Boca de indio Carbón Costillo Fono Granadillo Guacharaco Guarango Kinde Laurel Marfil Nacedero Palma Bombona Palma Cachuda Palma Milpes Perillo x x x x x goals, pedagogical units with printed materials, and activities (Table 1). The pedagogical units included contents that were considered necessary to establish future ecological restoration goals, and for the comprehension of technical and organizational options (Supplement S1, Fig. 2). represented 1 ha of farmland and others represented money for economic transactions. Using monetary and yield values previously established for each activity, a group of participants chose the alternatives for the available areas. For practical thinking, activities such as seed collection, seedling production, outplantings, and field visits were implemented (Fig. S1). These practical activities were oriented to design different restoration strategies such as forest enrichment, riparian ecosystem restoration, silvopastoral, or agroforestry systems (“productive restoration” sensu Ceccon 2013) that could serve as models to share with other groups. At each meeting, the peasants shared their reflections about the prior educative session. The evaluation of learning was focused at the group level, not individuals. Their ideas before and after each meeting and results of practical activities were recorded by observers from the SINCHI Institute and are presented below. Results Beginning the Educative Process With the Peasants In 2017, SLS developed the ecological restoration-based education program with five pedagogical units supported by printed material on the topic to be addressed: (1) soils; (2) farm planning, (3) river basins, (4) monitoring, and (5) social organization (Table 1). LS with collaboration of researchers and technicians of SINCHI implemented the program in 23 rural localities. The number of participants in each educational meeting ranged between 7 and 70 (Table S1). Each unit of the educative program was implemented in a specific meeting in each locality, over the course of 2018 (five meetings per locality over the year). In addition to reflections about the printed pedagogical materials, critical thinking was promoted with the game “How much do we know about the soil?” (CSIC 2015). In this activity, a group of peasants roll a dice, whose resulting number leads to a box with questions. According to the answer, the group moves forward or backward in the boxes. Each answer was discussed among peasants, LS, and researchers. For creative thinking, another game, called “make decisions and plan your farm” was used (adapted from Viera 2006). The game consisted of a set of cards with 12 land use alternatives, including several forest restoration strategies. Other cards September 2020 Restoration Ecology x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x New Ideas in Developing During the meetings, the previous and new ideas were systematized and recorded in five categories by LS and SINCHI researchers (Table S2) as follows: (1) Change of previous ideas: Peasants’ previous ideas were that water and soil were “inexhaustible resources.” They also agreed that they did not know anything about river basins and their importance for soil and water conservation. They also recognized that they could not understand the complexity of the native forest and were unaware of the possibility of losing soil productivity permanently. After the 1057 1526100x, 2020, 5, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/rec.13216 by Universidad Nacional Colombia, Wiley Online Library on [14/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License Restoration and education in Colombian Amazon Figure 3 Local leaders (“local scientists”) working with peasants in the ecological restoration-based program. (A) Sharing knowledge about species among peasants; (B) recognizing fruit and seeds of some species; (C) making a herbarium; (D) group of local peasants and local scientists in educative meeting. course, they affirmed that in the future, local communities will be able to detect erosive processes and make better decisions to avoid them. (2) Ideas that require more deep analysis and complementary training: In contents about planning and ecological restoration, generalized previous ideas were that native forest could not offer enough income to assure an acceptable quality of life. Based on this reasoning, people 55–60 years old would generally be willing to sell their farms and move to the town. There was also a consensus among different working groups that younger people preferred to sell their farms to buy cheaper lands in the jungle, where the soil has higher nutrient contents, rather than improving management practices to enhance the soil quality and increase their crop yields. Peasants also mentioned that no productive system could compete with the high annual profitability of coca crops. After the educative work on economic evaluation of alternative farm management, peasants recognized that the high profitability of coca crops or cattle grazing only lasts for a short time, because they degrade soils and quickly reduce their productivity. Peasants found profitability possibilities in agroforestry and agroecological systems using their traditional ecological knowledge and government technical assistance for the implementation. In fact, they 1058 selected some native species for this purpose (see Tables 1 and S3). The project offered a first opportunity for ecological and economic planning of farms, although more educational work is required. The management is based on a learning process to improve long-term outcomes. However, in Caquetá alternative management is just beginning. Ecological restoration is a new idea in the region and has not yet been fully embraced by peasants. After the pedagogical unit, they concluded that at present, without governmental subsidies they would not be able to invest in ecological restoration. (3) Ideas considered valuable but that could be applied only in the future: Peasants stated that they had never heard about the issue of monitoring. After the educative meeting, they expressed that the experience was interesting and proposed several indicators for monitoring forest enrichment, riparian ecosystem restoration, agroforestry systems, and silvopastoral systems (Table S4). This issue was not considered for immediate application in restorative interventions, but useful for the future. (4) New procedural knowledge: This is the knowledge exercised in the performance of some task (Guzman 2009). In the project several tasks were learned. Seed collection and seedling production were carried out in 2019 (Fig. S1). Nursery gardens were installed on 71 farms of program Restoration Ecology September 2020 1526100x, 2020, 5, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/rec.13216 by Universidad Nacional Colombia, Wiley Online Library on [14/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License Restoration and education in Colombian Amazon participants with their own labor, 21 native forest species were propagated, and 400,000 seedlings were produced (Table 2). In 2019, with technical and financial support from the LS, peasants established restoration plots in 277 farms over 550 ha (Fig. S2). Restorative interventions were considered “living classrooms” for the project to acquire practical knowledge in the future. (5) Attitudes about social organization: These are ideas about feelings, values, motivations, and beliefs (Hungerford & Volk 1990). The peasants agreed that there was a schism between the education system and the ecological and social needs of the community. Peasants considered that the future role of the LS is to keep working together with peasants and promoting their participation in decision-making spaces, such as in the territorial councils. The relationship between peasants and LS established between 2017 and 2019 has been strong enough to support continuity of educative process through the present (2020); hopefully, this will continue in the future. Discussion The process of ecological restoration-based education allowed: (1) the collective recognition of erroneous and degrading land management practices, (2) a knowledge dialogue leading to the recovery of local traditional ecological knowledge, and (3) establishment of new land management possibilities. Ecological restoration-based education also provided learning at two levels: (1) a group of educative multipliers (LS) and (2) local peasants. LS were educators, but they were also essentially peers of the peasants with additional training and experience in socioecological issues. On the other hand, LS gained access to new knowledge, not only from pedagogical materials but through sharing experiences with peasants. In this sense, we can consider this educative process of “reciprocal teaching.” The pedagogical materials were catalyst mediators for the interaction between peasants and LS, and are now permanently available for use in the communities. Restored plots are now places that promote new meetings, consolidate established networks, and promote new knowledge. Due to the short duration of the process described in this article; it is not yet clear whether there has been a lasting conceptual change in the local land use models. According to McCann (2011), time is an important variable in the educative and restorative process. If over time restoration makes sense for local people and constitutes a better model of their relationship with nature, they will be more likely to change their land use practices (McGinnis 2005). This is not a quick task or merely the acquisition of a “catalog” of good practices, but a continuous and progressive learning process working toward the resolution of socioecological conflicts. This is an endless process that must be maintained through social organization. Thus, the challenge in Caquetá is just beginning (Fig. 3). Rather than centering on a number of hectares of forest to be recovered as a solution for degradation or benchmark for success; the project in Caquetá has focused on changing the utilitarian and extractivist relationship with nature that was established by the September 2020 Restoration Ecology historical context of the region. For this goal, the main strategy was RBE and the strengthening of local capacities for future sustainability. RBE, as shown in this article, offers to expand environmental learning for all ages, the opportunity to build new links with nature, to establish new social relationships, and simultaneously contribute to peace, social justice, and ecosystem restoration. Acknowledgments We thank the Alma Foundation, which accompanied the design and implementation of the pedagogical strategy during the years 2017 and 2018. We also thank J. Valero, D. Sierra, D. Rondon, and A. Lopez for their helpful work in developing the pedagogical materials and modules and to all the peasants who are part of the school of LS. D.R.P. thanks the research project 04-U021, and members of the Laboratory of Rehabilitation and Restoration of Arid and Semi-Arid Ecosystems (LARREA) of the National University of Comahue (Argentina) for various contributions and opinions on this article. E.C. is thankful for the support of PAPIIT-UNAM IN300119. We also thank P. Meli for the valuable comments. LITERATURE CITED Aguilar M, Sierra J, Ramírez W, Vargas O, Calle Z, Vargas W, Murcia C, Aronson J, Barrera Cataño JI (2015) Toward a post-conflict Colombia: restoring to the future. Restoration Ecology 23:4–6 Armenteras D, Rodríguez N, Retana J, Morales M (2011) Understanding deforestation in montane and lowland forests of the Colombian Andes. Regional Environmental Change 11:693–705 Ausubel D, Novak J, Hanesian H (1978) Educational psychology: a cognitive view. 2nd edition. Holt, Rinehart & Winston, New York http://files.eric. ed.gov/fulltext/ED247712.pdf (accessed 23 Oct 2019) Becerra-Ordoñez LC, Bernal-Perilla LT, Rodríguez-Pérez W (2014) Evaluación del nivel de degradación de suelo y pastura en tres geoformas de Florencia-Caquetá. Momentos de Ciencia 11:83–88 http://www.udla.edu. co/revistas/index.php/momentos-de-ciencia/article/view/484 (accessed 23 Oct 2019) Bloomfield G, Bucht K, Martínez-Hernández JC, Ramírez-Soto AF, SheseñaHernández I, Lucio-Palacio CR, Ruelas Inzunza E (2018) Capacity building to advance the United Nations sustainable development goals: an overview of tools and approaches related to sustainable land management. Journal of Sustainable Forestry 37:157–177 Ceccon E (2013) Restauración en bosques tropicales: fundamentos ecológicos, prácticos y sociales. CRIM UNAM – Díaz de Santos, México ISBN 978-84-9969-615-7 Clerici N, Salazar C, Pardo-Díaz C, Jiggins CD, Richardson JE, Linares M (2018) Peace in Colombia is a critical moment for Neotropical connectivity and conservation: save the northern Andes–Amazon biodiversity bridge. Conservation Letters 12: 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12594 Colmenares A (2012) Investigación-acción participativa: una metodología integradora del conocimiento y la acción. Voces y Silencios: Revista Latinoamericana de Educación 3:112–115 CSIC (2015) El juego del Suelo. http://www.suelos2015.es/materiales/juego/ juego-del-suelo (accessed 23 Oct 2019) Etter A, McAlpine C, Wilson K, Phinn S, Possingham H (2006) Regional patterns of agricultural land use and deforestation in Colombia. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 114:369–386 Fink LD (2003) A self-directed guide to designing courses for significant learning instructional development program. University of Oklahoma, Norman. 1059 1526100x, 2020, 5, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/rec.13216 by Universidad Nacional Colombia, Wiley Online Library on [14/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License Restoration and education in Colombian Amazon Gonzalez-Salazar MA, Venturini M, Poganietz WR, Finkenrath M, Leal M (2017) Combining an accelerated deployment of bioenergy and land use strategies: review and insights for a post-conflict scenario in Colombia. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 73:159–177 Guzman G (2009) What is practical knowledge. Journal of Knowledge Management 4:86–98 Hensley N (2013) Curriculum as bioregional text: place, experience, and sustainability. Journal of Sustainability Education 5:1–9 Hungerford HR, Volk TL (1990) Changing learner behavior through environmental education. The Journal of Environmental Education 21:8–21 IDEAM (2018) Tasa anual de deforestación en Colombia (1990–2017). http://www. ideam.gov.co/documents/11769/648879/4.03+D+Tasa+deforestacion+Dptos. xlsx/304987a5-cdec-49ff-9e26-2062f4e22acf (accessed 23 Oct 2019) Janzen DH (1988) Tropical ecological and biocultural restoration. Science, New Series 239:243–244 Köppen W (1936) Das geographische system der klimate. Handbuch der klimatologie. Verlag Gebrüder Borntraeger, Berlin, Germany Leff E (2010) Latin American environmental thought: a heritage of knowledge for sustainability. ISEE, Publicación Ocasional 9:1–16 www.cep.unt.edu/ papers/leff-eng.pdf (accessed 4 Sept 2019) McGinnis MV (2005) Bioregionalism. Taylor & Francis e-Library and Routledge, New York McCann E (2011) Restoration based education: teach the children well. Pages 315–334. In: Egan D, Hjerpe EE, Abrams J (eds), Human dimensions of ecological restoration. Island Press, Washington D.C. Meli P, Schweizer D, Brancalion PHS, Murcia C, Guariguata MR (2019) Multidimensional training among Latin America’s restoration professionals. Restoration Ecology 27:477–484 Murad C, Pearse J (2018) Landsat study of deforestation in the Amazon region of Colombia: departments of Caquetá and Putumayo. Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment 1:161–171 Murcia C, Kattan GH, Andrade-Pérez GI (2013) Conserving biodiversity in a complex biological and social setting: the case of Colombia. Pages 86–96. In: Sodhi NS, Gibson L, Raven PH (eds) Conservation biology: voices from the tropics. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Hoboken, New Jersey. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118679838.ch11 Naderifar M, Goli H, Ghaljaie F (2017) Snowball sampling: a purposeful method of sampling in qualitative research. Strides in Development of Medical Education 14: 1–3. https://doi.org/10.5812/sdme.67670 Niño Arcila O, González Leon G, Gutierrez Rey F, Rodriguez Salazar A (2000) Caquetá. construcción de un territorio amazónico en el siglo XX. Instituto de investigaciones Científicas – SINCHI y Tercer Mundo, Bogotá ISBN 958-968781-4 Orr DW (1992) Ecological literacy: education and the transition to a postmodern world. Albany: Suny Press, State University of New York Pérez DR, González FM, Rodriguez Araujo ME, Paredes DA, Farinaccio FM, Chrobak R, Meinardi E (2017) Ecological restoration based on environmental education in arid regions of the Patagonia. Pages 4–54. In: Ceccon E, Pérez DR (Coords.). Mazzini V (ed) Beyond restoration ecology: social perspectives in Latin America and the Caribbean Pérez DR, González F, Rodríguez Araujo ME, Paredes D, Meinardi E (2019) Restoration of society-nature relationship based on education: a model and progress in Patagonian drylands. Ecological Restoration 37: 182–191 Sauvé L (2005) Currents in environmental education: mapping a complex and evolving pedagogical field. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education 10:11–34 SINCHI (2013) Restauración de áreas degradadas por implementación de sistemas productivos agropecuarios en el Caquetá-Colombia-convenio 060. Instituto de Investigaciones Amazónicas SINCHI. Caquetá. Colombia, Florencia UN (2020) United Nations. Strategy of the United Nations Decade on Ecosystem Restoration. www.decaderestoration.org (accessed 20 Apr 2020) UNESCO (2013) Situación educativa de América Latina y el Caribe: Hacia la educación de calidad para todos al 2015. Oficina de Santiago Oficina Regional de Educación para América Latina y el Caribe, Santiago, Chile Valerio K (2012) Intrinsic motivation in the classroom. Journal of Student Engagement: Education Matters 2:30–35 Viera M (2006) Aplicación de un juego de rol y un modelo multiagentes como propuesta para el estudio del cambio de cobertura de la tierra en la zona de colonización del Guaviare (Amazonia colombiana). (Tesis de pregrado en Ecología). Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá, Colombia Vosniadou S (2007) Conceptual change and education. Human Development 50: 47–54 Coordinating Editor: Stephen Murphy Received: 22 April, 2020; First decision: 15 May, 2020; Revised: 21 May, 2020; Accepted: 29 May, 2020 1060 Supporting Information The following information may be found in the online version of this article: Supplement S1. Educative methodological design of the ecological restoration. Restoration Ecology September 2020 1526100x, 2020, 5, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/rec.13216 by Universidad Nacional Colombia, Wiley Online Library on [14/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License Restoration and education in Colombian Amazon