Risk Score for Intracranial Hemorrhage in Patients With

Anuncio

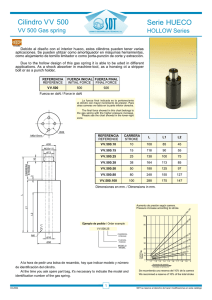

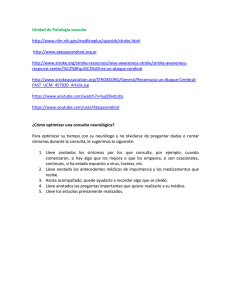

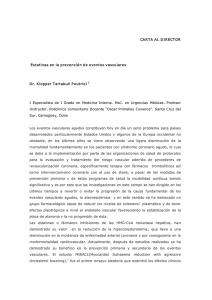

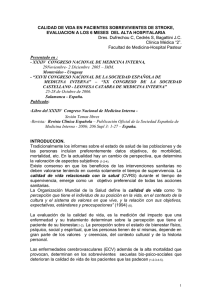

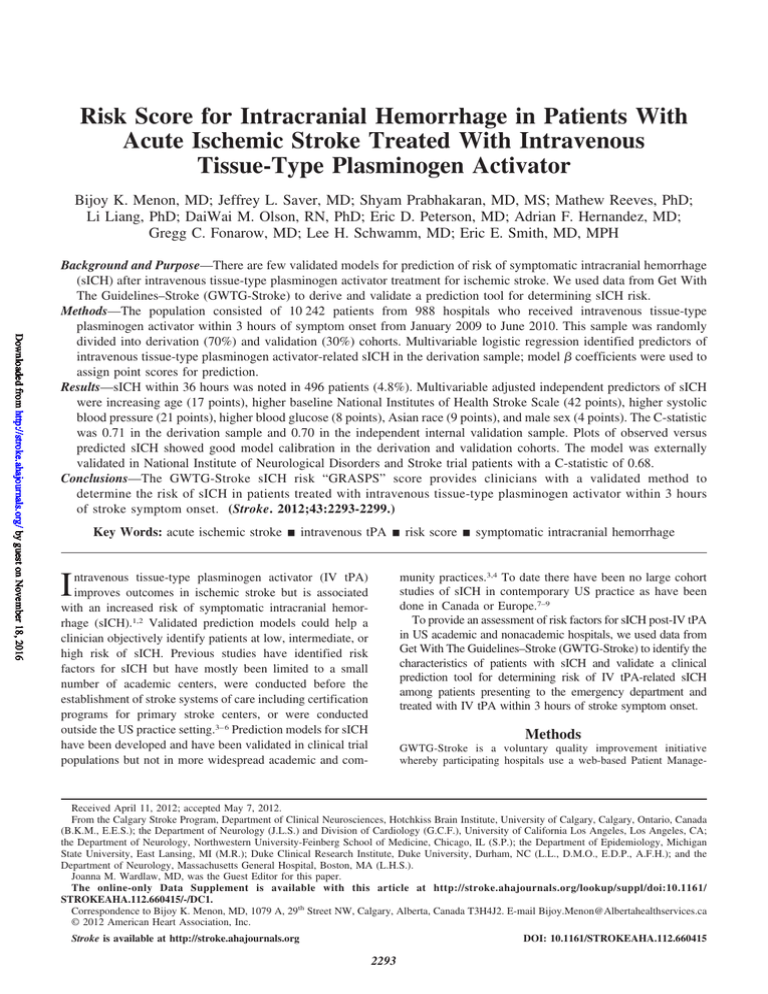

Risk Score for Intracranial Hemorrhage in Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke Treated With Intravenous Tissue-Type Plasminogen Activator Bijoy K. Menon, MD; Jeffrey L. Saver, MD; Shyam Prabhakaran, MD, MS; Mathew Reeves, PhD; Li Liang, PhD; DaiWai M. Olson, RN, PhD; Eric D. Peterson, MD; Adrian F. Hernandez, MD; Gregg C. Fonarow, MD; Lee H. Schwamm, MD; Eric E. Smith, MD, MPH Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on November 18, 2016 Background and Purpose—There are few validated models for prediction of risk of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage (sICH) after intravenous tissue-type plasminogen activator treatment for ischemic stroke. We used data from Get With The Guidelines–Stroke (GWTG-Stroke) to derive and validate a prediction tool for determining sICH risk. Methods—The population consisted of 10 242 patients from 988 hospitals who received intravenous tissue-type plasminogen activator within 3 hours of symptom onset from January 2009 to June 2010. This sample was randomly divided into derivation (70%) and validation (30%) cohorts. Multivariable logistic regression identified predictors of intravenous tissue-type plasminogen activator-related sICH in the derivation sample; model  coefficients were used to assign point scores for prediction. Results—sICH within 36 hours was noted in 496 patients (4.8%). Multivariable adjusted independent predictors of sICH were increasing age (17 points), higher baseline National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (42 points), higher systolic blood pressure (21 points), higher blood glucose (8 points), Asian race (9 points), and male sex (4 points). The C-statistic was 0.71 in the derivation sample and 0.70 in the independent internal validation sample. Plots of observed versus predicted sICH showed good model calibration in the derivation and validation cohorts. The model was externally validated in National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke trial patients with a C-statistic of 0.68. Conclusions—The GWTG-Stroke sICH risk “GRASPS” score provides clinicians with a validated method to determine the risk of sICH in patients treated with intravenous tissue-type plasminogen activator within 3 hours of stroke symptom onset. (Stroke. 2012;43:2293-2299.) Key Words: acute ischemic stroke 䡲 intravenous tPA 䡲 risk score 䡲 symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage I ntravenous tissue-type plasminogen activator (IV tPA) improves outcomes in ischemic stroke but is associated with an increased risk of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage (sICH).1,2 Validated prediction models could help a clinician objectively identify patients at low, intermediate, or high risk of sICH. Previous studies have identified risk factors for sICH but have mostly been limited to a small number of academic centers, were conducted before the establishment of stroke systems of care including certification programs for primary stroke centers, or were conducted outside the US practice setting.3– 6 Prediction models for sICH have been developed and have been validated in clinical trial populations but not in more widespread academic and com- munity practices.3,4 To date there have been no large cohort studies of sICH in contemporary US practice as have been done in Canada or Europe.7–9 To provide an assessment of risk factors for sICH post-IV tPA in US academic and nonacademic hospitals, we used data from Get With The Guidelines–Stroke (GWTG-Stroke) to identify the characteristics of patients with sICH and validate a clinical prediction tool for determining risk of IV tPA-related sICH among patients presenting to the emergency department and treated with IV tPA within 3 hours of stroke symptom onset. Methods GWTG-Stroke is a voluntary quality improvement initiative whereby participating hospitals use a web-based Patient Manage- Received April 11, 2012; accepted May 7, 2012. From the Calgary Stroke Program, Department of Clinical Neurosciences, Hotchkiss Brain Institute, University of Calgary, Calgary, Ontario, Canada (B.K.M., E.E.S.); the Department of Neurology (J.L.S.) and Division of Cardiology (G.C.F.), University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA; the Department of Neurology, Northwestern University-Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL (S.P.); the Department of Epidemiology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI (M.R.); Duke Clinical Research Institute, Duke University, Durham, NC (L.L., D.M.O., E.D.P., A.F.H.); and the Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (L.H.S.). Joanna M. Wardlaw, MD, was the Guest Editor for this paper. The online-only Data Supplement is available with this article at http://stroke.ahajournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1161/ STROKEAHA.112.660415/-/DC1. Correspondence to Bijoy K. Menon, MD, 1079 A, 29th Street NW, Calgary, Alberta, Canada T3H4J2. E-mail Bijoy.Menon@Albertahealthservices.ca © 2012 American Heart Association, Inc. Stroke is available at http://stroke.ahajournals.org DOI: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.660415 2293 2294 Stroke September 2012 ment Tool (Outcomes Sciences Inc, Cambridge, MA) to collect clinical data, access decision support, and provide real-time online reporting of performance on quality-of-care measures. Details of the program have been described previously.10 Information is abstracted from the medical record and uploaded to the database with automated checks for data validity. Post-IV tPA sICH is defined as neurological worsening within 36 hours of tPA administration that is attributed to ICH verified by CT or MRI, as documented in the chart by the treating physician. This definition is based on the criteria for sICH in the 1995 National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) trial.1 Participating institutions are required to comply with local regulatory and privacy guidelines and to submit the GWTG protocol for review and approval by their local Institutional Review Board. Because data are used primarily at the local site for quality improvement, sites are granted a waiver of informed consent under the common rule. The Duke Clinical Research Institute served as the data analysis center and had local Institutional Review Board approval to conduct the study. Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on November 18, 2016 Study Population We included patient admissions from January 1, 2009. to June 30, 2010. During this time there were 13 481 patients with ischemic stroke who presented to the emergency department within 3 hours and were treated with IV tPA. By design, we did not include 3171 patients treated with IV tPA after 3 hours, 568 patients treated with IV tPA for in-hospital acute ischemic stroke, and 243 patients treated with tPA with unknown time from stroke symptom onset. Among the 13 481 patients presenting directly to the emergency department who were treated within 3 hours, a total of 3239 (24%) were excluded for the following reasons: (1) investigational or experimental protocol for thrombolysis (n⫽117 [0.9%]); (2) transfer in from a different hospital (n⫽732 [5.4%]); (3) transfer out to another hospital within 2 days thus precluding information on the presence or absence of sICH within 36 hours (n⫽268 [2%]); (4) missing information on discharge outcome (n⫽71 [0.5%]); (5) missing National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score (a critical covariate, n⫽1342 [9.9%]); (6) international normalized ratio ⬎1.7 (above the cutoff recommended by the US Food and Drug Administration drug labeling, n⫽73 [0.5%]); and (7) treatment with intra-arterial therapies (n⫽552 [4.1%]). Additionally, data from 13 hospitals providing 84 patients (0.6%) were excluded because ⬍75% of the data submitted from these hospitals were complete, raising questions regarding the accuracy of the data. The final study population of 10 242 patients was randomly divided into derivation (70%) and validation (30%) cohorts (online-only Data Supplement Figure I). The randomly selected derivation cohort and validation cohort were well matched with respect to candidate predictor variables and outcome (data not shown). Candidate Predictor Variables Potential predictor variables were determined based on prior knowledge, causal relevance, and availability of data in the Patient Management Tool. A complete list of candidate variables is available as an online-only Data Supplement. Statistical Analysis The rates of sICH were reported in each group for categorical variables. The sICH rates were compared across the groups using Pearson 2 test for categorical variables and Cochran-MantelHaenszel test using row-mean score statistic for the continuous variables. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to identify independent predictors of sICH performed in the derivation sample (70%). Within-hospital clustering was accounted for using a generalized estimating equation approach with exchangeable working correlation matrix. Continuous covariates were evaluated for appropriateness of the linearity assumption using plots displaying the relationship of each variable with the log odds of sICH. When appropriate, knots were determined to create splines (variables that were modeled equivalent to piece-linear continuous variables). Age, door-to-needle time, and international normalized ratio were included as continuous variables because of a linear relationship with log odds of sICH throughout their range. Baseline NIHSS, systolic blood pressure, heart rate, and blood glucose showed ceiling effects and thus were truncated. The remaining continuous variables were modeled as splines with nonsignificant splints removed from the reduced model. In addition, we tested for interactions between (1) warfarin use on admission and international normalized ratio; and (2) past medical history of diabetes mellitus and prior stroke/transient ischemic attack. The reduced model included only important predictors chosen based on statistical significance in the multivariable model and clinical relevance. The discriminatory ability of the model was assessed using the C-statistic, which represents the probability that the model would correctly predict that the risk was higher for a patient who had sICH versus a patient who did not. Calibration of the model was assessed by Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic and by the plots comparing predicted versus observed probability of sICH. The reduced model was then validated by assessing model performance, that is, discrimination and calibration in the validation cohort (30%). The selected reduced model was refit using the whole sample to develop a risk score by assigning a weighted integer to each independent predictor based on the predictor’s  coefficient. For each patient, the weighted integers were summed to obtain a total risk score with a range of 0 to 101 points. Continuous variables included in the reduced final model were categorized into appropriate clinically relevant categories and the categories were used to derive the risk score. This risk score was then assessed for discrimination with C-statistic and calibration by comparing predicted versus observed sICH rates. The model was also externally validated in IV tPA-treated patients from the 1995 NINDS trial (n⫽309 after excluding 2 patients with missing glucose values). All probability values are 2-sided with P⬍0.05 considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SAS software (Version 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Results The final study population consisted of 10 242 patients from 988 hospitals. Mean age was 69.9⫾14.7 years, median baseline NIHSS was 11 (interquartile range, 7–18), and median time from stroke symptom onset to IV tPA treatment was 135 minutes (interquartile range, 110 –160 minutes). Patients were treated at hospitals with median bed size 375 (interquartile range, 270 –558), most patients were treated in teaching hospitals (55.5%), and 34.5% patients were treated in hospitals administering ⱕ6 IV tPA cases a year. sICH within 36 hours was noted in 496 (4.8%) patients. Patients with sICH, compared with patients without sICH, were older (mean age, 75.3 versus 69.6 years; P⬍0.0001), had higher initial stroke severity (median NIHSS, 17 versus 11; P⬍0.0001), higher systolic blood pressure (median, 159 mm Hg versus 154 mm Hg; P⬍0.0001), and higher blood glucose values (median, 126 mg/dL versus 118 mg/dL; P⬍0.0001). Risk of sICH according to sex, medical comorbidities, and medication use is shown in Table 1. The “in-hospital” mortality rate was 175 of 487 (35.9%) in patients with sICH and 629 of 9604 (6.5%) in those without sICH after excluding 151 patients transferred to other acute care hospitals. Multivariable modeling in the derivation sample identified increasing age, higher baseline NIHSS, higher systolic blood pressure, higher blood glucose, Asian race, and male sex as independent predictors of IV tPA-related sICH. C-statistic in the derivation sample was 0.71 (95% CI, 0.68 – 0.73) and the Hosmer-Lemeshow test probability value was 0.78. In the independent validation sample, the C-statistic was 0.70 (95% Menon et al Risk Score for sICH With IV tPA Table 1. Rate of IV tPA-Related Symptomatic Intracranial Hemorrhage According to Patient and Hospital Characteristics (Nⴝ10 242) Characteristic Category No. Percent ICH After IV tPA P Value ⱕ60 61–70 71–80 ⬎80 Male Female 0–5 6–10 11–15 16–20 ⬎20 Missing Other Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander White Asian American Indian or Alaska Native Black or African American Hispanic ⱖ180 150–179 120–149 ⬍120 ⱖ150 100–149 ⬍100 ⱕ1.1 1.1–1.7 ⬎1.7 ⱕ1.7 Yes No Yes No 2762 2061 2522 2897 5203 5035 1875 2876 2146 1803 1542 313 50 21 7539 236 26 1391 664 2054 4009 3372 807 2388 6172 1682 8700 1542 748 9494 805 9346 4352 5822 2.6 4 5.6 7 5 4.7 2.2 2.7 4.6 7.5 9.3 6.6 2 9.5 4.9 10.6 0 3.7 4.5 6.5 5.2 3.9 2.7 5.9 4.9 3.1 4.6 6.0 4.6 4.9 6.3 4.7 5.9 4.1 ⬍0.001 Atrial fibrillation Yes No 2114 7232 6.9 4.3 ⬍0.001 Previous stroke/TIA Yes No 2444 6902 4.7 5 0.623 CAD Yes No 2747 6599 6 4.4 0.002 Diabetes mellitus Yes No 2478 6868 5.4 4.7 0.163 Hypertension Yes No 7398 1948 5.4 2.9 ⬍0.001 Smoker Yes No 1898 7448 2.9 5.4 ⬍0.001 Dyslipidemia Yes No 3945 5401 5.4 4.5 0.041 Heart failure Yes No 806 8540 6.9 4.7 0.005 Hospital type Nonacademic Academic Missing 3790 5679 773 5 4.7 5.1 0.46 Age, y Sex NIHSS Race Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on November 18, 2016 Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg Blood glucose, mg/dL INR Serum creatinine, mg/dl Anticoagulant before admission Antiplatelet drug before admission 0.41 ⬍0.001 ⱕ0.001 ⬍0.001 ⬍0.001 0.018 0.694 0.04 ⬍0.001 IV tPA indicates intravenous tissue-type plasminogen activator; ICH, intracranial hemorrhage; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; INR, international normalized ratio; TIA, transient ischemic attack; CAD, coronary artery disease. 2295 2296 Stroke September 2012 Table 2. Refitted Multivariate Model Using the Entire Study Sample (nⴝ10 242) OR Lower 95% CI of OR Upper 95% CI of OR P Value NIHSS per 1 unit up to maximum 20 1.09 1.08 1.12 ⬍0.001 Age per 10 y 1.26 1.17 1.35 ⬍0.001 Systolic BP per 10 mm Hg up to maximum 180 1.12 1.07 1.17 ⬍0.001 Blood glucose per 10 mg/dL up to maximum 150 1.06 1.02 1.11 0.003 Variable Female versus male 0.71 0.59 0.87 0.001 Asian versus non-Asian 2.12 1.28 3.50 0.004 C-statistic 0.71 and Hosmer-Lemeshow test P value 0.48. NIHSS indicates National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; BP, blood pressure. Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on November 18, 2016 CI, 0.67– 0.74) and the Hosmer-Lemeshow test probability value was 0.18. Because good validation was demonstrated, the model was then refitted using the whole study sample; the C-statistic was 0.71 and the Hosmer-Lemeshow test probability value was 0.48. Model results are presented in Table 2. Secondary analyses show no interaction among warfarin use, increased international normalized ratio, and the risk of sICH (P⫽0.42). No statistical interaction was observed between history of diabetes mellitus and history of prior stroke in predicting risk of sICH (P⫽0.49). Risk Score A risk score was created by assigning a weighted integer to each of the 6 independent predictors (Table 2) based on the predictor’s  coefficient and summing them to obtain a total risk score with a range of 45 to 101 points (Figure 1). The risk score demonstrated good discrimination (C-statistic 0.70) and good calibration from a plot of predicted versus observed sICH (P⫽0.35 for Hosmer-Lemeshow test). There was good correlation between predicted and observed risk of sICH across a wide range of predicted risk in the derivation and validation cohorts (Figure 2A). Likewise, a plot of observed versus predicted sICH in the validation cohort showed strong correlation (Figure 2B). The C-statistic for the model in the NINDS trial patients was 0.68 (Figure 3). Discussion In this study, we identified risk factors for sICH after IV tPA and used this information to derive and validate a risk score for predicting risk of symptomatic ICH. This “GRASPS” clinical risk score has 6 predictor variables: Glucose at presentation, Race (Asian), Age, Sex (male), systolic blood Figure 1. Risk score for symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage after IV tPA. IV tPA indicates intravenous tissue-type plasminogen activator. Menon et al Risk Score for sICH With IV tPA 2297 Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on November 18, 2016 Figure 2. A, Calibration of the prediction tool in the derivation and validation samples according to observed versus predicted rate of sICH post-IV tPA in 6 prespecified risk categories. B, Plot of observed versus predicted rate of sICH in the independent validation sample (n⫽3071) according to decile of predicted risk. sICH indicates symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage; IV tPA, intravenous tissue-type plasminogen activator. Pressure at presentation, and Severity of stroke at presentation (NIHSS). This clinical risk prediction tool (www. strokeassociation.org/GWTGsICHcalculator) uses clinical variables readily available at the time of presentation with acute ischemic stroke. The c-statistic of 0.71 indicates good discriminatory ability in predicting sICH in patients who present within 3 hours of stroke symptom onset and are treated with IV tPA. The score also has good calibration indicating how closely the predicted risk agrees with the actual risk of sICH. Other risk scores for post IV tPA sICH have been published. The Hemorrhage After Thrombolysis (HAT) score Figure 3. Observed versus predicted rate of sICH according to quartile of predicted risk in the NINDS IV tPA data set, n⫽309. sICH indicates symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage; NINDS, National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; IV tPA, intravenous tissue-type plasminogen activator. includes stroke severity at presentation (NIHSS), presence of hyperglycemia or diabetes, and hypodensity on baseline CT.3 The c-statistic for the validation cohort was 0.74, similar to ours. The HAT score has also been externally validated in clinical trial populations but not always with the same discriminatory ability: the C-statistic was 0.72 in a subsequent validation using data from the Combined Lysis of Thrombus in Brain Ischemia Using Transcranial Ultrasound and Systemic tPA (CLOTBUST) and Transcranial Ultrasound in Clinical Sonothrombolysis (TUCSON) studies but only 0.61 in the Stroke-Acute Ischemic NXY Treatment (SAINT)-I and SAINT-II trials.3,11,12 The Multicenter Recombinant Tissue Plasminogen Activator Stroke Survey Group developed a 4-point risk score that included age ⬎60 years, NIHSS ⬎10, glucose ⬎8.325 mmol/L, and platelet count ⬍150 000/mm3.4 This score had a C-statistic of 0.69 in their data set and 0.61 in subsequent validation in the SAINT-I and SAINT-II trials.4,11 Both of these studies derived the risk scores from relatively small cohorts and did not report on calibration.3,4 The C-statistic is dependent on case mix, disease severity, and prevalence of risk factors in the cohort. Model discrimination should therefore be better when the cohort is large and representative rather than highly selected, like in a clinical trial. Calibration should also be reported as a measure of model performance.13 Our model calibration and discrimination were good and validated well externally in data from the NINDS trial. Additional studies will be needed to determine the external validity of our risk score and to compare our risk score with previously published scores. 2298 Stroke September 2012 Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on November 18, 2016 Our study confirms known associations with higher stroke severity, higher blood glucose, and higher blood pressure.3,9,14 –16 Our results, however, suggest that there is increasing risk with increasing systolic blood pressure even when the systolic blood pressure is ⬍185 mm Hg. A limitation of our study is that only initial blood pressure and glucose were recorded without longitudinal assessments. Therefore, we are unable to determine the extent to which acute treatment of elevated blood pressure or glucose might have mitigated the risk of subsequent tPA-related sICH. Ours is the first study to report on male sex and Asian race as independent predictors of IV tPA-related sICH, although they account for a relatively small amount of variation in sICH risk. It is important to note that the increased risk of ICH associated with male sex and Asian race is modest and does not appear sufficient to justify withholding IV tPA from an otherwise eligible patient. We failed to find an association between IV tPA-related sICH and elevated international normalized ratio or warfarin use in contrast to 2 previous single-center studies17,18 but consistent with findings from the Registry of the Canadian Stroke Network.19 We also failed to find an association between sICH and the combination of previous stroke and diabetes, which was an exclusion criterion in the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study (ECASS) III study.2 We failed to find an association between prestroke antiplatelet drug use and sICH in patients receiving IV tPA within 3 hours. In an analysis of data from the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study (SITS-MOST) registry,9 prestroke aspirin use was associated with an increased risk of sICH using the SITS-MOST definition of ICH but not when using the definition of ICH used in the NINDS trial.1 However, we did not have data on the number, type or dose of agent, and cannot exclude an increased risk in patients on combined aspirin and clopidogrel as has been suggested in some studies.5,20 Our study has some limitations. Patients and hospitals may not be entirely representative because hospital participation in GWTG-Stroke is voluntary. Nonetheless, the demographics of the GWTG-Stroke patient population are quite similar to the overall demographics of all US patients with stroke.10 We used a definition of sICH based on the 1995 NINDS trial definition that attributes clinical worsening to ICH documented on CT or MRI based on the investigator’s judgment. This definition is different from the ECASS II definition in which clinical deterioration is defined as a 4-point increase in NIHSS or the SITS-MOST definition in which, in addition, only parenchymal hemorrhages Type 2 can be considered symptomatic.8,21 We are not able to test our prediction score predicting sICH by these other definitions because we do not have information on hemorrhage type or posthemorrhage NIHSS. sICH events were determined by the treating physicians and not centrally reviewed; however, the very large difference in mortality between patients with and without sICH suggests that the sICH events were clinically relevant. Our risk score performed nearly as well in the NINDS trial in which the sICH events were prospectively recorded and centrally reviewed. Neuroimaging data were not available in the database. We were, however, able to predict the risk of IV tPA-related sICH with similar discrimination as risk scores that rely on neuroimaging findings.3 We chose to analyze data from patients treated ⬍3 hours after symptom onset, consistent with current US Food and Drug Administration labeling for IV tPA for acute ischemic stroke and therefore cannot be certain whether the same risk factors for sICH are relevant to patients treated beyond 3 hours. We also cannot be certain that the same risk factors predict in-hospital stroke, because patients with in-hospital stroke were excluded. Finally, we excluded 11.1% of patients because of missing information that could have introduced some selection bias. In summary, the “GRASPS score” is a well-validated, evidence-based determination of the risk of sICH in patients treated with IV tPA within 3 hours of stroke symptom onset that provides clinicians, patients, and families an objective understanding of the risks involved with this treatment. The score should not be used to infer which patients would derive the most or least benefit from IV tPA because neither the “GRASPS score” nor its components have been shown to modify the effect of IV tPA treatment. The score could be used to facilitate quality improvement by allowing hospitals to determine whether their rate of sICH exceeds the expected rate predicted by the score. Calculation of the score can be facilitated by use of applications on handheld devices or by a score calculator accessed on the Internet. An application for calculating the score for individuals or groups of patients is available on the web-based patient management tool for GWTG-Stroke (www.strokeassociation.org/GWTGsICHcalculator) enabling hospitals to calculate predicted risk for groups of patients. Sources of Funding The American Heart Association and the American Stroke Association fund Get With the Guidelines–Stroke. The program is also supported in part by unrestricted educational grants to the American Heart Association by Pfizer, Inc, New York, NY, and the MerckSchering Plough Partnership (North Wales, PA), who did not participate in the design, analysis, article preparation, or approval. Disclosures Dr Schwamm is a member of the Steering Committee for the Desmoteplase in Acute Ischemic Stroke Trial (DIAS)-3 trial funded by Lundbeck and is employed by Massachusetts General Hospital, which has received IV tPA from Genentech as part of a National Institutes of Health-sponsored clinical trial. References 1. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rtPA Stroke Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1581–1587. 2. Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, Brozman M, Davalos A, Guidetti D, et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1317–1329. 3. Lou M, Safdar A, Mehdiratta M, Kumar S, Schlaug G, Caplan L, et al. The HAT score: a simple grading scale for predicting hemorrhage after thrombolysis. Neurology. 2008;71:1417–1423. 4. Cucchiara B, Tanne D, Levine SR, Demchuk AM, Kasner S. A risk score to predict intracranial hemorrhage after recombinant tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;17: 331–333. 5. Cucchiara B, Kasner SE, Tanne D, Levine SR, Demchuk A, Messe SR, et al. Factors associated with intracerebral hemorrhage after thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke: pooled analysis of placebo data from the Menon et al 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on November 18, 2016 11. 12. 13. 14. Stroke-Acute Ischemic NXY Treatment (SAINT) I and SAINT II trials. Stroke. 2009;40:3067–3072. Demchuk AM, Morgenstern LB, Krieger DW, Linda Chi T, Hu W, Wein TH, et al. Serum glucose level and diabetes predict tissue plasminogen activator-related intracerebral hemorrhage in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 1999;30:34 –39. Nadeau JO, Shi S, Fang J, Kapral MK, Richards JA, Silver FL, et al. tPA use for stroke in the registry of the Canadian Stroke Network. Can J Neurol Sci. 2005;32:433– 439. Wahlgren N, Ahmed N, Davalos A, Ford GA, Grond M, Hacke W, et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase for acute ischaemic stroke in the Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis in Stroke-Monitoring Study (SITS-MOST): an observational study. Lancet. 2007;369:275–282. Wahlgren N, Ahmed N, Eriksson N, Aichner F, Bluhmki E, Davalos A, et al. Multivariable analysis of outcome predictors and adjustment of main outcome results to baseline data profile in randomized controlled trials: Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis in Stroke-Monitoring Study (SITS-MOST). Stroke. 2008;39:3316 –3322. Reeves MJ, Fonarow GC, Smith EE, Pan W, Olson D, Hernandez AF, et al. Representativeness of the Get With The Guidelines–Stroke registry: comparison of patient and hospital characteristics among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2012;43:44 – 49. Cucchiara B, Kasner S, Tanne D, Levine S, Demchuk A, Messe S, et al. Validation assessment of risk scores to predict postthrombolysis intracerebral haemorrhage. Int J Stroke. 2011;6:109 –111. Tsivgoulis G, Saqqur M, Barreto A, Demchuk AM, Ribo M, Rubiera M, et al. Validity of hat score for predicting symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage in acute stroke patients with proximal occlusions: data from randomized trials of sonothrombolysis. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;31:471–476. Cook NR. Use and misuse of the receiver operating characteristic curve in risk prediction. Circulation. 2007;115:928 –935. Sylaja PN, Cote R, Buchan AM, Hill MD. Thrombolysis in patients older than 80 years with acute ischaemic stroke: Canadian alteplase 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. Risk Score for sICH With IV tPA 2299 for stroke effectiveness study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006; 77:826 – 829. Tsivgoulis G, Frey JL, Flaster M, Sharma VK, Lao AY, Hoover SL, et al. Pre-tissue plasminogen activator blood pressure levels and risk of symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2009;40:3631–3634. Ahmed N, Wahlgren N, Brainin M, Castillo J, Ford GA, Kaste M, et al. Relationship of blood pressure, antihypertensive therapy, and outcome in ischemic stroke treated with intravenous thrombolysis: Retrospective analysis from Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis in StrokeInternational Stroke Thrombolysis Register (SITS-ISTR). Stroke. 2009; 40:2442–2449. Prabhakaran S, Rivolta J, Vieira JR, Rincon F, Stillman J, Marshall RS. Symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage among eligible warfarin-treated patients receiving intravenous tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:559 –563. Seet RC, Zhang Y, Moore SA, Wijdicks EF, Rabinstein AA. Subtherapeutic international normalized ratio in warfarin-treated patients increases the risk for symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage after intravenous thrombolysis. Stroke. 2011;42:2333–2335. Vergouwen MD, Casaubon LK, Swartz RH, Fang J, Stamplecoski M, Kapral MK. Subtherapeutic warfarin is not associated with increased hemorrhage rates in ischemic strokes treated with tissue plasminogen activator. Stroke. 2011;42:1041–1045. Hermann A, Dzialowski I, Koch R, Gahn G. Combined anti-platelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel: risk factor for thrombolysis-related intracerebral hemorrhage in acute ischemic stroke? J Neurol Sci. 2009; 284:155–157. Hacke W, Kaste M, Fieschi C, von Kummer R, Davalos A, Meier D, et al. Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial of thrombolytic therapy with intravenous alteplase in acute ischaemic stroke (ECASS II). Second European-Australasian Acute Stroke Study investigators. Lancet. 1998;352:1245–1251. Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on November 18, 2016 Risk Score for Intracranial Hemorrhage in Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke Treated With Intravenous Tissue-Type Plasminogen Activator Bijoy K. Menon, Jeffrey L. Saver, Shyam Prabhakaran, Mathew Reeves, Li Liang, DaiWai M. Olson, Eric D. Peterson, Adrian F. Hernandez, Gregg C. Fonarow, Lee H. Schwamm and Eric E. Smith Stroke. 2012;43:2293-2299; originally published online July 17, 2012; doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.660415 Stroke is published by the American Heart Association, 7272 Greenville Avenue, Dallas, TX 75231 Copyright © 2012 American Heart Association, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0039-2499. Online ISSN: 1524-4628 The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is located on the World Wide Web at: http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/43/9/2293 Data Supplement (unedited) at: http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/suppl/2012/07/17/STROKEAHA.112.660415.DC1.html http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/suppl/2013/10/02/STROKEAHA.112.660415.DC2.html http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/suppl/2016/04/10/STROKEAHA.112.660415.DC3.html Permissions: Requests for permissions to reproduce figures, tables, or portions of articles originally published in Stroke can be obtained via RightsLink, a service of the Copyright Clearance Center, not the Editorial Office. Once the online version of the published article for which permission is being requested is located, click Request Permissions in the middle column of the Web page under Services. Further information about this process is available in the Permissions and Rights Question and Answer document. Reprints: Information about reprints can be found online at: http://www.lww.com/reprints Subscriptions: Information about subscribing to Stroke is online at: http://stroke.ahajournals.org//subscriptions/ Supplemental Material Risk Score for Intracranial Hemorrhage in Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke Treated With Intravenous t-PA. Candidate Predictor Variables: Patient specific variables included demographics (age, gender, race, baseline stroke severity by NIHSS), past medical history (prior stroke/TIA, CAD, prior MI, prosthetic heart valve, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation, smoking, dyslipidemia, heart failure, COPD/asthma, peripheral vascular disease, renal insufficiency, on dialysis), laboratory parameters including blood glucose, Creatinine and INR, vital signs including systolic blood pressure and heart rate on admission, interval times and prior medications. Hospital level variables included number of beds, geographic region, teaching status and number of acute ischemic strokes admitted and administered IV t-PA per year. Less than 5% of data were missing for most candidate variables except blood glucose (21%). Based on prior studies suggesting that hyperglycemia is a risk factor for sICH, we retained serum glucose in the models and imputed missing values to the median value for diabetics or non-diabetics, depending on whether the patient had a history of diabetes. Otherwise, for categorical variables missing data were imputed to the most common category, and for continuous variables to the median value. We performed a sensitivity analysis and re-ran the final prediction model in patients with complete information that met all study inclusion criteria. This study sample has 7938 (77.5%) patients, and there are 366 sICH after IV tPA in this sample (4.61%). The model c statistic was the same in patients with complete information (c statistic 0.71, Hosmer-Lemeshow test p value=0.25) compared to the c statistic in the overall model including all patients (c statistic 0.71, Hosmer-Lemeshow test p value=0.48), showing that the prediction score works similarly well in patients with complete information. Supplemental Figure 1:Study population criteria 1286531 patients from 1563 hospitals (1 April 2003 to 30 June 2010) 443,969 ischemic stroke patients (1 January 2009 to 30 June 2010 13481 ischemic stroke patients who presenting to the ED within 3 hours and were treated with IV t-PA Final Study Population (N=10242) Records entered prior to 1 January 2009 (prior to requirement for complete laboratory information to be entered) (N=842562) Not included: 1) Non ischemic strokes (N=175780) 2) Did not receive IV tPA (N=250726) 3) Unknown time of stroke onset (N=243) 4) Onset to needle time>3 hours (N=3171) 5) In hospital stroke (N=568) Additional Exclusions: 1) Investigational or experimental protocol for thrombolysis (n=117) 2) Transfer-in from a different hospital (n=732) 3) Transfer-out to another hospital within 2 days thus precluding information on the presence or absence of sICH within 36 hours (n=268) 4) Treatment with intra-arterial therapies (n=552) 5) INR >1.7 (above the cut-off recommended by the U.S. F.D.A. drug labeling, n=73) 6) Missing information (11.1%): a) Missing discharge outcome (n=71) b) Missing NIH stroke scale score (a critical covariate, n=1342) c) Patients from hospitals with <75% data completion (n=84 from 13 hospitals) Abstract 33 Abstract 組織型プラスミノゲン活性化因子の静脈内投与を受けた急性 期虚血性脳卒中患者における頭蓋内出血のリスクスコア Risk Score for Intracranial Hemorrhage in Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke Treated With Intravenous Tissue-Type Plasminogen Activator Bijoy K. Menon, MD1; Jeffrey L. Saver, MD2; Shyam Prabhakaran, MD, MS4; Mathew Reeves, PhD5; Li Liang, PhD6; DaiWai M. Olson, RN, PhD6; Eric D. Peterson, MD6; Adrian F. Hernandez, MD6; Gregg C. Fonarow, MD3; Lee H. Schwamm, MD7; Eric E. Smith, MD, MPH1 1 Calgary Stroke Program, Department of Clinical Neurosciences, Hotchkiss Brain Institute, University of Calgary, Calgary, Ontario, Canada; Department of Neurology and 3 Division of Cardiology , University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA; 4 Department of Neurology, Northwestern University-Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL; 5 Department of Epidemiology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI; 6 Duke Clinical Research Institute, Duke University, Durham, NC; 7 Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA. 2 背景および目的:虚血性脳卒中のため組織型プラスミノ ゲン活性化因子の静脈内投与を受けた後の症候性頭蓋内 出血( sICH )のリスクを予測する検証済みモデルはほとん どない。我々は Get With The Guidelines-Stroke( GWTGStroke )研究のデータを使用して,sICH のリスクを決定す るための予測方法を導き出し,検証を行った。 方法:対象集団は,2009 年 1 月から 2010 年 6 月までに 発症から 3 時間以内に組織型プラスミノゲン活性化因子の 静脈内投与を受けた 988 病院の 10,242 例の患者で構成さ れた。この対象集団を,導出( derivation )コホート( 70%) と検証( validation )コホート( 30%)に無作為に分けた。多 変量ロジスティック回帰分析の結果,導出コホートにおけ る組織型プラスミノゲン活性化因子の静脈内投与関連の sICH の予測因子が同定された。予測のポイントスコアの 割り当てにはモデルの B 係数を使用した。 結果:36 時間以内の sICH が 496 例の患者( 4.8%)に認め られた。多変量補正後の sICH の独立予測因子は,年齢が 高いこと( 17 ポイント) ,ベースラインの米国国立衛生研 究所脳卒中スケール( NIHSS )が高いこと( 42 ポイント) , 収縮期血圧が高いこと (21 ポイント) ,血糖値が高いこと (8 ポイント) ,アジア人であること( 9 ポイント) ,男性であ ること( 4 ポイント)であった。C 統計量は,導出コホート では 0.71,独立した内部検証コホートでは 0.70 であった。 実際の sICH と予測された sICH のプロットから,導出コ ホートと検証コホートにおいてモデルの良好な計測結果が 示された。国立神経疾患・脳卒中研究所( NINDS )試験患 者を対象に我々のモデルの外部検証を行ったところ,C 統 計量は 0.68 であった。 結論:GWTG-Stroke 研究に基づいた sICH リスク 「GRASPS」 スコアは,脳卒中の発症から 3 時間以内に組織型プラスミ ノゲン活性化因子の静脈内投与を受けた患者の sICH リス クを決定する検証済みの方法を臨床医に提供する。 Stroke 2012; 43: 2293-2299 12 10 表2 8 実際のsICHの 6 リスク(%) 4 試験対象全体を用いて再適合させた多変量モデル (n = 10,242) 変数 NIHSS (1 単位ごと,最大 20) 年齢(10 歳ごと) OR 1.09 OR の下側 OR の上側 95% CI 95% CI 1.08 1.12 p値 < 0.001 1.26 1.17 1.35 < 0.001 収縮期 BP 1.12 (10 mm Hg ごと,最大 180) 1.07 1.17 < 0.001 血糖値 (10 mg/dL ごと,最大 150) 1.06 1.02 1.11 0.003 女性対男性 0.71 0.59 0.87 0.001 アジア人対非アジア人 2.12 1.28 3.50 0.004 C 統計量 0.71,Hosmer-Lemeshow 検定の p 値 0.48。 NIHSS:米国国立衛生研究所脳卒中スケール(National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale),BP:血圧。 2 0 1(2%) 2(3.5%) 3(5.8%) 4(10.2%) 4つのリスクカテゴリーにおける予測されたsICHのリスクカテゴリー(%) ■NINDS IV tPAデータセットの検証コホートn=309[C統計量0.68] NINDS IV tPA データセット( n = 309 )を用いて予測リ スクの四分位群別にみた sICH の実際の発生率と予測発生 率の比較。 図3 sICH:症候性頭蓋内出血,NINDS:国立神経疾患・脳卒 中研究所,IV tPA:組織型プラスミノゲン活性化因子の静 脈内投与。 Puntuación de riesgo de hemorragia intracraneal en pacientes con ictus isquémico agudo tratados con activador de plasminógeno de tipo tisular intravenoso Bijoy K. Menon, MD; Jeffrey L. Saver, MD; Shyam Prabhakaran, MD, MS; Mathew Reeves, PhD; Li Liang, PhD; DaiWai M. Olson, RN, PhD; Eric D. Peterson, MD; Adrian F. Hernandez, MD; Gregg C. Fonarow, MD; Lee H. Schwamm, MD; Eric E. Smith, MD, MPH Antecedentes y objetivo—Existen pocos modelos validados para la predicción del riesgo de hemorragia intracraneal sintomática (HICs) después del tratamiento del ictus isquémico con activador de plasminógeno de tipo tisular intravenoso. Hemos utilizado los datos de Get With the Guidelines–Stroke (GWTG-Stroke) para elaborar a partir de ellos y validar un instrumento de predicción para la determinación del riesgo de HICs. Métodos—La población la formaron 10.242 pacientes de 988 hospitales que recibieron tratamiento con activador de plasminógeno de tipo tisular intravenoso en un plazo de 3 horas desde el inicio de los síntomas, entre enero de 2009 y junio de 2010. Esta muestra se dividió aleatoriamente en una cohorte de elaboración del instrumento (70%) y una cohorte de validación (30%). La regresión logística multivariada identificó factores predictivos de las HICs asociada al uso de plasminógeno de tipo tisular intravenoso en la muestra de elaboración; se utilizaron coeficientes β para asignar puntuaciones de predicción. Resultados—Se observó una HICs en un plazo de 36 horas en 496 pacientes (4,8%). Los factores predictivos de la HICs independientes en el modelo multivariado ajustado fueron la edad creciente (17 puntos), el valor basal de la escala National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (42 puntos), la presión arterial sistólica más alta (21 puntos), la glucemia más alta (8 puntos), la raza asiática (9 puntos) y el sexo masculino (4 puntos). El valor del estadístico C fue de 0,71 en la muestra de elaboración y de 0,70 en la muestra de validación interna independiente. Los gráficos de las HICs observadas frente a las esperadas mostraron un buen calibrado del modelo en las cohortes de elaboración y de validación. El modelo fue validado externamente en pacientes del ensayo del National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke con un valor del estadístico C de 0,68. Conclusiones—La puntuación de riesgo GWTG-Stroke sICH “GRASPS” proporciona al clínico un método validado para determinar el riesgo de HICs en pacientes tratados con activador de plasminógeno de tipo tisular intravenoso en un plazo de 3 horas tras el inicio de los síntomas de ictus. (Traducido del inglés: Risk Score for Intracranial Hemorrhage in Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke Treated With Intravenous Tissue-Type Plasminogen Activator. Stroke. 2012;43:2293-2299.) Palabras clave: acute ischemic stroke n intravenous tPA n risk score n symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage E l activador de plasminógeno de tipo tisular intravenoso (tPA i.v.) mejora los resultados clínicos en el ictus isquémico, pero se asocia a un aumento del riesgo de hemorragia intracraneal sintomática (HICs)1,2. Los modelos de predicción validados podrían facilitar al clínico la identificación objetiva de pacientes de riesgo bajo, intermedio o alto de HICs. En estudios previos se han identificado factores de riesgo para la HICs pero en su mayoría estos estudios se han limitado a un número reducido de centros, se llevaron a cabo antes del establecimiento de los sistemas de asistencia de ictus que incluyen programas de certificación para centros especializados en ictus, o se han realizado fuera del contexto Recibido el 11 de abril de 2012; aceptado el 7 de mayo de 2012. Calgary Stroke Program, Department of Clinical Neurosciences, Hotchkiss Brain Institute, University of Calgary, Calgary, Ontario, Canadá (B.K.M., E.E.S.); Department of Neurology (J.L.S.) and Division of Cardiology (G.C.F.), University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA; Department of Neurology, Northwestern University-Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL (S.P.); Department of Epidemiology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI (M.R.); Duke Clinical Research Institute, Duke University, Durham, NC (L.L., D.M.O., E.D.P., A.F.H.); y Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (L.H.S.). Joanna M. Wardlaw, MD, fue la Editora Invitada para este artículo. El suplemento de datos de este artículo, disponible solamente online, puede consultarse en http://stroke.ahajournals.org/lookup/suppl/ doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.660415/-/DC1. Remitir la correspondencia a Bijoy K. Menon, MD, 1079 A, 29th Street NW, Calgary, Alberta, Canadá T3H4J2. Correo electrónico Bijoy.Menon@ Albertahealthservices.ca © 2012 American Heart Association, Inc. Puede accederse a Stroke en http://stroke.ahajournals.org 122 DOI: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.660415 Menon y cols. Puntuación de riesgo de hemorragia intracraneal en pacientes con ictus isquémico agudo 123 de asistencia médica de EEUU3–6. Se han elaborado modelos de predicción de las HICs que han sido validados en poblaciones de ensayos clínicos pero no en un ámbito académico y de asistencia médica de carácter más amplio3,4. Hasta la fecha no se han realizado estudios de cohorte amplios sobre la HICs en la práctica médica actual de EEUU, como los que se han hecho en Canadá o Europa7–9. Con objeto de llevar a cabo una evaluación de los factores de riesgo para la HICs después del tratamiento con tPA i.v. en hospitales académicos y no académicos de EEUU, hemos utilizado los datos de Get With the Guidelines–Stroke (GWTG-Stroke) para identificar las características de los pacientes con HICs y para validar un instrumento de predicción clínica para la determinación del riesgo de HICs asociada al tPA i.v. en pacientes que acuden al servicio de urgencias y son tratados con tPA i.v. en un plazo de 3 horas tras el inicio de los síntomas. Métodos La GWTG-Stroke es una iniciativa de mejora de calidad de carácter voluntario en la que los hospitales participantes utilizan a través de Internet un Patient Management Tool (Outcomes Sciences Inc, Cambridge, MA, EEUU) para la recogida de los datos clínicos, para acceder a medios de ayuda a la decisión y para notificar online en tiempo real el resultado de las medidas de valoración de la calidad de la asistencia. Anteriormente se ha publicado una descripción detallada del programa10. La información se extrae a partir de las historias clínicas y se introduce en la base de datos con verificaciones automáticas de la validez de los datos. La HICs post-tPA i.v. se define como un agravamiento neurológico en las 36 horas siguientes a la adminstración de tPA, que se atribuye a una HIC verificada mediante TC o RM, según lo documentado en la historia clínica por el médico encargado del tratamiento. Esta definición se basa en los criterios de HICs del ensayo del National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) de 19951. Los centros participantes tienen que cumplir las regulaciones locales y las directrices de privacidad y deben presentar el protocolo de la GWTG a su consejo de revisión interno local para su examen y aprobación. Dado que los datos se emplean fundamentalmente en el centro local para la mejora de la calidad, los centros están exentos de la exigencia de consentimiento informado según la normativa ordinaria. El Duke Clinical Research Institute actuó como centro de análisis de datos y dispuso de la aprobación del consejo de revisión interno local para la realización del estudio. Población en estudio Incluimos los ingresos de pacientes entre el 1 de enero de 2009 y el 30 de junio de 2010. Durante este tiempo hubo 13.481 pacientes con ictus isquémico que fueron atendidos en el servicio de urgencias en un plazo de 3 horas y tratados con tPA i.v. Dado el diseño del estudio, no incluimos a 3.171 pacientes tratados con tPA i.v. después de las 3 primeras horas, a 568 pacientes tratados con tPA i.v. por un ictus isquémico agudo sufrido en el hospital y a 243 pacientes tratados con tPA después de transcurrido un intervalo de tiempo desconocido tras el inicio de los síntomas de ictus. De los 13.481 pacientes que acudieron directamente al servicio de urgencias y que fueron tratados en un plazo de 3 horas, un total de 3.239 (24%) fueron excluidos por las siguientes razones: (1) protocolo de investigación o experimental para la trombolisis (n = 117 [0,9%]); (2) traslado procedente de otro hospital (n = 732 [5,4%]); (3) traslado a otro hospital antes de los 2 días, lo cual impedía obtener información sobre la presencia o ausencia de HICs en las primeras 36 horas (n = 268 [2%]); (4) falta de información sobre la evolución clínica en el momento del alta (n = 71 [0,5%]); (5) falta de información sobre la puntuación de la escala National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) (una covariable crucial, n = 1.342 [9,9%]); (6) ratio normalizada internacional > 1,7 (superior al valor de corte recomendado por el prospecto del fármaco aprobado por la Food and Drug Administration de EEUU, n = 73 [0,5%]); y (7) tratamiento con terapias intraarteriales (n = 552 [4,1%]). Además, se excluyeron los datos de 13 hospitales que aportaron 84 pacientes (0,6%) debido a que estaban completos < 75% de los datos que presentaron estos hospitales, lo cual planteaba dudas acerca de la exactitud de la información aportada. La población final en estudio de 10.242 pacientes se dividió aleatoriamente en una cohorte de elaboración (70%) y una cohorte de validación (30%) (Suplemento de Datos Online, Figura I). La cohorte de elaboración y la cohorte de validación establecidas de forma aleatoria estaban bien igualadas en cuanto a las diversas variables predictivas candidatas y en cuanto a los resultados obtenidos (datos no presentados). Variables predictivas candidatas Las posibles variables predictivas candidatas se determinaron en función de los conocimientos previos, la relevancia causal y la disponibilidad de datos en el Patient Management Tool. Puede consultarse la relación completa de las variables candidatas en el Suplemento de Datos Online. Análisis estadístico Se determinaron las tasas de HICs en cada grupo para las variables discretas. Las tasas de HICs de los diversos grupos se compararon con la prueba de χ2 de Pearson para las variables discretas y con la prueba de Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel, utilizando el estadístico de puntuación media de fila, para las variables continuas. Se utilizó un análisis de regresión logística multivariado para identificar factores predictivos independientes para la HICs en la muestra de elaboración (70%). Se tuvo en cuenta el agrupamiento dentro del mismo hospital para el uso de un método de ecuación de estimación generalizada con una matriz de correlación operativa intercambiable. Se evaluó si las covariables continuas eran apropiadas en cuanto al supuesto de linealidad con el empleo de gráficos que mostraban la relación de cada variable con el valor de log odds de la HICs. En los casos apropiados, se determinaron los nudos para crear splines (variables que se introdujeron en el modelo de manera equivalente a variables continuas con fragmentos lineales). La edad, el tiempo puerta-aguja y la ratio normalizada internacional se incluyeron como variables continuas, dada la relación lineal existente con el valor de log odds de la HICs en todo su rango de valores. El valor basal de la NIHSS, la presión arterial sistólica, la frecuencia cardiaca y la glucemia mostraron un efecto techo, y por tanto se truncaron. Las demás variables continuas se introdujeron 124 Stroke Noviembre 2012 Tabla 1. Tasa de hemorragias intracraneales sintomáticas asociadas al tPA i.v. según las características del paciente y el hospital (N=10.242) Característica Categoría Edad, años Número Porcentaje de HIC después de tPA i.v. Valor de p 60 61–70 71–80 80 Sexo Varones Mujeres NIHSS 0–5 6–10 11–15 16–20 20 Raza No disponible Otras Nativos de Hawai/islas del Pacífico Blancos Asiáticos Nativos indios norteamericanos o de Alaska Negros o afroamericanos Hispanos Presión arterial sistólica, mmHg 180 150–179 120–149 120 Glucemia, mg/dL 150 100–149 100 INR 1,1 1,1–1,7 Creatinina sérica, mg/dL 1,7 1,7 Anticoagulante antes de ingreso Sí No Antiagregante plaquetario antes de ingreso Sí No 2.762 2.061 2.522 2.897 5.203 5.035 1.875 2.876 2.146 1.803 1.542 313 50 21 7.539 236 26 1.391 664 2.054 4.009 3.372 807 2.388 6.172 1.682 8.700 1.542 748 9.494 805 9.346 4.352 5.822 2,6 4 5,6 7 5 4,7 2,2 2,7 4,6 7,5 9,3 6,6 2 9,5 4,9 10,6 0 3,7 4,5 6,5 5,2 3,9 2,7 5,9 4,9 3,1 4,6 6,0 4,6 4,9 6,3 4,7 5,9 4,1 Fibrilación auricular Sí No 2.114 7.232 6,9 4,3 0,001 Ictus/AIT previo Sí No 2.444 6.902 4,7 5 0,623 EC Sí No 2.747 6.599 6 4,4 0,002 Diabetes mellitus Sí No 2.478 6.868 5,4 4,7 0,163 Hipertensión Sí No 7.398 1.948 5,4 2,9 0,001 Fumador Sí No 1.898 7.448 2,9 5,4 0,001 Dislipidemia Sí No 3.945 5.401 5,4 4,5 0,041 Insuficiencia cardiaca Sí No 806 8.540 6,9 4,7 0,005 No académico Académico No disponible 3.790 5.679 773 5 4,7 5,1 0,46 Tipo de hospital 0,001 0,41 0,001 0,001 0,001 0,001 0,018 0,694 0,04 0,001 tPA i.v. indica activador de plasminógeno de tipo tisular intravenoso; HIC, hemorragia intracraneal; NIHSS National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; INR, ratio normalizada internacional; AIT, ataque isquémico transitorio; EC, enfermedad coronaria. Menon y cols. Puntuación de riesgo de hemorragia intracraneal en pacientes con ictus isquémico agudo 125 Tabla 2. Modelo multivariado reajustado, que utiliza la totalidad de la muestra del estudio (n=10.242) Variable Límite inferior Límite superior del IC del 95% del IC del 95% Valor OR de la OR de la OR de p NIHSS por 1 unidad hasta un máximo de 20 1,09 1,08 1,12 0,001 Edad por 10 años 1,26 1,17 1,35 0,001 PA sistólica por 10 mmHg hasta un máximo de 180 1,12 1,07 1,17 0,001 Glucemia por 10 mg/dL hasta un máximo de 150 1,06 1,02 1,11 0,003 Mujeres frente a varones 0,71 0,59 0,87 0,001 Asiáticos frente a no asiáticos 2,12 1,28 3,50 0,004 Estadístico C 0,71 y valor de p en la prueba de Hosmer-Lemeshow 0,48. NIHSS indica National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; PA, presión arterial. en el modelo como splines, eliminando los splints no significativos del modelo reducido. Por otra parte, se evaluaron las interacciones entre (1) uso de warfarina al ingreso y ratio normalizada internacional; y (2) antecedentes previos de diabetes mellitus e ictus/ataque isquémico transitorio previo. El modelo reducido incluyó solamente los factores predictivos importantes elegidos en función de su significación estadística en el modelo multivariado y de su relevancia clínica. La capacidad discriminativa del modelo se evaluó con el estadístico C, que corresponde a la probabilidad de que el modelo pudiera predecir correctamente que el riesgo era mayor para un paciente con HICs en comparación con un paciente sin este trastorno. El calibrado del modelo se evaluó mediante el estadístico de Hosmer-Lemeshow y mediante los gráficos de comparación de la probabilidad esperada frente a la probabilidad observada de HICs. El modelo reducido se validó evaluando su rendimiento, es decir, la discriminación y el calibrado en la cohorte de validación (30%). El modelo reducido elegido se volvió a ajustar con el empleo de la muestra completa, para desarrollar una puntuación de riesgo mediante la asignación de un entero ponderado a cada factor predictivo independiente, basándose en el coeficiente β del factor predictivo. Para cada paciente, se sumaron los enteros ponderados para obtener una puntuación de riesgo total, con valores de entre 0 y 101 puntos. Las variables continuas incluidas en el modelo final reducido se clasificaron en categorías clínicamente relevantes y apropiadas, y esas categorías se utilizaron para la elaboración de la puntuación de riesgo. Esta puntuación de riesgo se evaluó entonces para determinar su capacidad de discriminación con Figura 1. Puntuación de riesgo para la hemorragia intracraneal sintomática después del tratamiento con tPA i.v. tPA i.v. indica activador de plasminógeno de tipo tisular intravenoso. 126 Stroke Noviembre 2012 A B el estadístico C y su calibrado mediante la comparación de las tasas de HICs esperadas con las observadas. También se validó el modelo externamente en pacientes tratados con tPA i.v. del ensayo de 1995 del NINDS (n=309 después de excluir a 2 pacientes con valores de glucosa no disponibles). Todos los valores de probabilidad son bilaterales y se considera estadísticamente significativo un valor de p < 0,05. Los análisis se realizaron con el programa SAS, versión 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, EEUU). Figura 3. Tasa de HICs observada frente a la esperada según el cuartil del riesgo predicho en el conjunto de datos de tPA i.v. del NINDS, n=309. HICs indica hemorragia intracraneal sintomática; NINDS, National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; tPA i.v., activador de plasminógeno de tipo tisular intravenoso. Figura 2. A, Calibrado del instrumento de predicción en las muestras de elaboración y de validación, según la tasa de HICs post-tPA observada frente a la esperada en 6 categorías de riesgo preespecificadas. B, Gráfico de la tasa de HICs observada frente a la esperada en la muestra independiente de validación (n=3.071) según el decil del riesgo esperado. HICs indica hemorragia intracraneal sintomática; tPA i.v., activador de plasminógeno de tipo tisular intravenoso. Resultados La población final en estudio la formaron 10.242 pacientes de 988 hospitales. La media de edad fue de 69,9±14,7 años, la mediana de la NIHSS basal fue de 11 (rango intercuartiles, 7–18) y la mediana de tiempo entre el inicio de los síntomas de ictus y el tratamiento con tPA i.v. fue de 135 minutos (rango intercuartiles, 110–160 minutos). Los pacientes fueron tratados en hospitales con una mediana de número de camas de 375 (rango intercuartiles, 270–558); la mayoría de los pacientes fueron tratados en hospitales docentes (55,5%), y un 34,5% de los pacientes fueron tratados en hospitales que tenían ≤6 casos de uso de tPA i.v. al año. Se observó una HICs en un plazo de 36 horas en 496 (4,8%) pacientes. Los pacientes con HICs, en comparación con los pacientes sin HICs, fueron de mayor edad (media de edad, 75,3 frente a 69,6 años; p < 0,0001), presentaron una mayor gravedad del ictus inicial (mediana NIHSS, 17 frente a 11; p < 0,0001), una presión arterial sistólica superior (mediana, 159 mmHg frente a 154 mmHg; p < 0,0001), y unos niveles de glucemia más elevados (mediana, 126 mg/dL frente a 118 mg/dL; p < 0,0001). En la Tabla 1 se presenta el riesgo de HICs según el sexo, las comorbilidades médicas y el uso de medicación. La tasa de mortalidad “en el hospital” fue de 175 de 487 (35,9%) en los pacientes con HICs y de 629 de 9.604 (6,5%) en los pacientes sin HICs, tras excluir a 151 pacientes trasladados a otros hospitales de asistencia aguda. El modelo multivariado realizado en la muestra de elaboración identificó la edad creciente, la NIHSS basal más alta, la presión arterial sistólica superior, la glucemia más Menon y cols. Puntuación de riesgo de hemorragia intracraneal en pacientes con ictus isquémico agudo 127 elevada, la raza asiática y el sexo masculino como factores predictivos independientes de la HIC asociada al tPA i.v.. El valor del estadístico C en la muestra de elaboración fue de 0,71 (IC del 95%, 0,68–0,73) y el valor de probabilidad de la prueba de Hosmer-Lemeshow fue de 0,78. En la muestra de validación independiente, el valor del estadístico C fue de 0,70 (IC del 95%, 0,67– 0,74) y el valor de probabilidad de la prueba de Hosmer-Lemeshow fue de 0,18. Dado que se demostró una buena validación, se volvió a ajustar el modelo con el empleo de la muestra de estudio total; el estadístico C fue de 0,71 y el valor de probabilidad de la prueba de Hosmer-Lemeshow fue de 0,48. Los resultados del modelo se presentan en la Tabla 2. Los análisis secundarios no mostraron interacción alguna entre el uso de warfarina, el aumento de la ratio normalizada internacional y el riesgo de HICs (p = 0,42). No se observaron interacciones estadísticas entre los antecedentes de diabetes mellitus y los antecedentes de un ictus previo en cuanto a la predicción del riesgo de HICs (p = 0,49). Puntuación de riesgo Se elaboró una puntuación de riesgo mediante la asignación de un entero ponderado a cada uno de los 6 factores predictivos independientes (Tabla 2) basándose en el coeficiente β del factor predictivo y sumándolos para obtener una puntuación de riesgo total, con un rango de 45 a 101 puntos (Figura 1). La puntuación de riesgo demostró una buena discriminación (estadístico C 0,70) y un buen calibrado a partir de un gráfico del valor esperado frente al valor observado de las HICs (p = 0,35 para la prueba de Hosmer-Lemeshow). Hubo una buena correlación entre el riesgo de HICs esperado y el observado dentro de una amplia gama de valores de riesgo esperado en las cohortes de elaboración y de validación (Figura 2A). De igual manera, un gráfico de las HICs observadas frente a las esperadas en la cohorte de validación mostró una correlación intensa (Figura 2B). El valor del estadístico C para el modelo en los pacientes del ensayo NINDS fue de 0,68 (Figura 3). Discusión En este estudio, identificamos factores de riesgo para la HICs tras el tratamiento con tPA i.v. y utilizamos esta información para elaborar y validar una puntuación de riesgo para la predicción del riesgo de HIC sintomática. Esta puntuación de riesgo clínica “GRASPS”(por sus siglas en inglés) incluye 6 variables predictivas: glucosa en el momento de presentación, raza (asiática), edad, sexo (masculino), presión arterial sistólica en el momento de la presentación inicial y gravedad del ictus (escala NIHSS) en el momento de la presentación inicial. Este instrumento de predicción del riesgo clínico (www.strokeassociation.org/GWTGsICHcalculator) utiliza variables clínicas fácilmente accesibles en el momento de la presentación inicial de un paciente con un ictus isquémico agudo. El estadístico C de 0,71 indica una buena capacidad de discriminación para predecir las HICs en los pacientes que acuden en un plazo de 3 horas tras el inicio de los síntomas de ictus y son tratados con tPA i.v. La puntuación tiene también un buen calibrado, que indica el grado de coincidencia del riesgo esperado con el riesgo real de HICs. Se han publicado otras puntuaciones de riesgo para la HICs post-tPA i.v. La puntuación Hemorrhage After Thrombolysis (HAT) incluye la gravedad del ictus (escala NIHSS) en el momento de la presentación inicial, la presencia de hiperglucemia o diabetes y la hipodensidad en la TC basal3. El estadístico C para la cohorte de validación fue de 0,74, similar al nuestro. La puntuación HAT ha sido validada también externamente en poblaciones de ensayos clínicos pero no siempre con la misma capacidad de discriminación: el estadístico C fue de 0,72 en una validación posterior realizada con los datos de los estudios Combined Lysis of Thrombus in Brain Ischemia Using Transcranial Ultrasound and Systemic tPA (CLOTBUST) y Transcranial Ultrasound in Clinical Sonothrombolysis (TUCSON) pero solo de 0,61 en la de los ensayos Stroke-Acute Ischemic NXY Treatment (SAINT)-I y SAINT-II3,11,12. El Multicenter Recombinant Tissue Plasminogen Activator Stroke Survey Group desarrolló una puntuación de riesgo de 4 puntos que incluía la edad > 60 años, la puntuación NIHSS > 10, la glucosa > 8,325 mmol/L y el recuento de plaquetas < 150.000/mm3 4. Esta puntuación tuvo un valor del estadístico C de 0,69 en su conjunto de datos y de 0,61 en una validación posterior en los ensayos SAINT-I y SAINT-II 4,11. Ambos estudios establecieron las puntuaciones de riesgo a partir de cohortes relativamente pequeñas y no presentaron el calibrado3,4. El estadístico C depende de la combinación de casos, la gravedad de la enfermedad y la prevalencia de los factores de riesgo que haya en la cohorte. Por consiguiente, la discriminación del modelo debe ser mejor cuando la cohorte es amplia y representativa, en comparación con lo que ocurre cuando se emplea una cohorte muy seleccionada, como la de un ensayo clínico. Debe presentarse el calibrado como medida del rendimiento que proporciona el modelo13. En nuestro modelo, el calibrado y la discriminación fueron buenos y se validaron bien externamente mediante los datos del ensayos NINDS. Serán necesarios nuevos estudios para determinar la validez externa de nuestra puntuación de riesgo y para comparar nuestra puntuación con las publicadas anteriormente. Nuestro estudio confirma las asociaciones conocidas con la mayor gravedad del ictus, la glucemia más alta y el valor superior de la presión arterial3,9,14–16. Sin embargo, nuestros resultados sugieren que hay un riesgo creciente con el aumento de la presión arterial sistólica a pesar de que esta sea < 185 mmHg. Una limitación de nuestro estudio es que tan solo se registró la presión arterial y la glucosa en la situación inicial, sin determinaciones longitudinales posteriores. Por consiguiente, no pudimos determinar el grado en el que el tratamiento agudo de la presión arterial o la glucosa elevadas podría haber atenuado el riesgo de una posterior HICs asociada al tPA. Este es el primer estudio que indica que el sexo masculino y la raza asiática son factores predictivos independientes de las HICs asociadas al tPA i.v., aunque su efecto explica una cantidad relativamente pequeña de la variación en el riesgo de HICs. Es importante señalar que el aumento del riesgo de HIC asociado al sexo masculino y a la raza asiática es modesto y no parece suficiente para justificar que no se emplee el tPA i.v. en un paciente que por lo demás sea considerado elegible. 128 Noviembre 2298 Stroke Stroke September2012 2012 No asociación entre las HICs asociadas Ourobservamos study confirms knownalguna associations with higher stroke al tPA i.v. y la elevación de la ratio normalizada internacional severity, higher blood glucose, and higher blood presosure. el uso a diferencia los 2 estudios 3,9,14de –16 warfarina, Our results, however, de suggest that thereprevios is in17,18 pero observarealizados cada uno en un solo centro creasing risk with increasing systolic bloodnuestra pressure even ción conblood los resultados del Registry of Hg. the Canadian whenconcuerda the systolic pressure is 185 mm A limita19 . Tampoco asociación Stroke tion ofNetwork our study is that observamos only initial una blood pressureentre and la HICs y la combinación de ictus previo y diabetes, que fue glucose were recorded without longitudinal assessments. un criterio de en to el determine estudio European Cooperative Therefore, weexclusión are unable the extent to which Acute Stroke Study (ECASS) III2. No hubo asociación entre el empleo de fármacos antiagregantes plaquetarios antes del ictus y la HICs en los pacientes tratados con tPA i.v. en un plazo de 3 horas. En un análisis de los datos del registro European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study (SITS-MOST)9, el empleo de ácido acetilsalicílico antes del ictus se asoció a un aumento del riesgo de HICs aplicando la definición de HIC del SITSMOST, pero no al utilizar la definición de HICs empleada en el ensayo NINDS1. Sin embargo, no dispusimos de datos sobre el número, tipo o dosis del fármaco, y no podemos descartar un aumento del riesgo en pacientes que reciben un tratamiento combinado de ácido acetilsalicílico y clopidogrel, tal como han sugerido algunos estudios5,20. Nuestro estudio tiene ciertas limitaciones. Es posible que los pacientes y los hospitales no sean totalmente representativos, ya que la participación de los hospitales en la GWTG-Stroke es voluntaria. No obstante, las características demográficas de la población de pacientes de la GWTG-Stroke son muy similares a las características demográficas globales del conjunto de pacientes con ictus de EEUU10. Utilizamos una definición de la HICs basada en la que se empleó en el ensayo del NINDS de 1995, que atribuye el agravamiento clínico a la HIC documentada en la TC o la RM según el criterio del investigador. Esta definición difiere de la del ECASS II, en la que el deterioro clínico se define como un aumento de 4 puntos en la escala NIHSS, o de la definición del SITS-MOST, en la que, además, solamente pueden considerarse sintomáticas las hemorragias parenquimatosas de tipo 28,21. No podemos poner a prueba nuestra puntuación predictiva aplicándola a la predicción de la HICs según estas otras definiciones, ya que no disponemos de información sobre el tipo de hemorragia ni sobre la NIHSS posterior a la hemorragia. Los episodios de HICs los determinaron los médicos encargados del tratamiento y no fueron objeto de una revisión centralizada; sin embargo, la diferencia de mortalidad muy grande observada entre los pacientes con y sin HICs sugiere que los episodios de HICs fueron clínicamente relevantes. Nuestra puntuación de riesgo tuvo un rendimiento casi igual de bueno en el ensayo NINDS, en el que los episodios de HICs se registraron prospectivamente y fueron revisados de forma centralizada. En la base de datos no se dispuso de información sobre los resultados de las técnicas de neuroimagen. Sin embargo, sí pudimos predecir el riesgo de HICs asociada al tPA i.v. con una discriminación similar a la que proporcionan las puntuaciones de riesgo que se basan en los signos de neuroimagen3. Optamos por analizar los datos de los pacientes tratados menos de 3 horas después del inicio de los síntomas, en consonancia con lo indicado en el prospecto actual aprobado por la Food and Drug Administration de EEUU para el tPA i.v. en el ictus isquémico agudo, y por tanto no podemos estar seguros de si estos mismos factores de riesgo para la HICs se dan también en los pacientes tratados después de las 3 primeras horas. Tampoco estar seguros de que tPA-related sICH with similar podemos discrimination as risk scores estos mismos factores de riesgo pueden predecir el ictus el that rely on neuroimaging findings.3 We chose to analyze en data hospital, ya que se excluyó a los pacientes que habían presenfrom patients treated 3 hours after symptom onset, consistadowith el ictus estando hospitalizados. último, excluimos al tent current US Food and Drug Por Administration labeling 11,1% de los pacientes por una falta de información que podría for IV tPA for acute ischemic stroke and therefore cannot be haber introducido un cierto sesgo de selección. certain whether the same risk factors for sICH are relevant to En resumen, la “puntuación GRASPS” es un método basapatients treated beyond 3 hours. We also cannot be certain do en la evidencia y bien validado para determinar el riesgo that the same risk factors predict in-hospital stroke, because de HICs en pacientes que reciben tratamiento con tPA i.v. en un plazo de 3 horas tras el inicio de los síntomas de ictus, y proporciona a clínicos, pacientes y familiares una información objetiva sobre los riesgos que comporta este tratamiento. La puntuación no debe usarse para inferir qué pacientes podrían obtener un mayor o menor beneficio con el uso de tPA i.v. ya que no se ha demostrado que la “puntuación GRASPS” ni sus componentes modifiquen el efecto del tratamiento con tPA i.v. La puntuación podría emplearse para facilitar una mejora de la calidad al permitir a los hospitales determinar si su tasa de HICs supera a la tasa esperada que predice la puntuación. El cálculo de la puntuación puede verse facilitado con el uso de aplicaciones para dispositivos móviles o con un instrumento que la calcule y al que pueda accederse a través de Internet. Puede utilizarse una aplicación para el cálculo de la puntuación en individuos o grupos de pacientes a la que puede accederse como Patient Management Tool en la web de GWTG-Stroke (www.strokeassociation.org/GWTGsICHcalculator); esta aplicación permite a los hospitales calcular el riesgo esperado en grupos de pacientes. Fuentes de financiación El fondo Get With the Guidelines–Stroke de la American Heart Association y la American Stroke Association. El programa cuenta también con financiación parcial mediante subvenciones de estudio no condicionadas concedidas a la American Heart Association por Pfizer, Inc, Nueva York, NY, y la Merck-Schering Plough Partnership (North Wales, PA), que no intervinieron en el diseño, análisis, preparación del artículo ni aprobación de éste. Declaraciones El Dr. Schwamm forma parte del comité de dirección del ensayo Desmoteplase in Acute Ischemic Stroke Trial (DIAS)-3, financiado por Lundbeck, y trabaja en el Massachusetts General Hospital, que ha recibido tPA i.v. por parte de Genentech como parte de un ensayo clínico patrocinado por los National Institutes of Health. Bibliografía 1. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rtPA Stroke Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1581–1587. 2. Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, Brozman M, Davalos A, Guidetti D, et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1317–1329. 3. Lou M, Safdar A, Mehdiratta M, Kumar S, Schlaug G, Caplan L, et al. The HAT score: a simple grading scale for predicting hemorrhage after thrombolysis. Neurology. 2008;71:1417–1423. 4. Cucchiara B, Tanne D, Levine SR, Demchuk AM, Kasner S. A risk score to predict intracranial hemorrhage after recombinant tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;17: 331–333. 5. Cucchiara B, Kasner SE, Tanne D, Levine SR, Demchuk A, Messe SR, et al. Factors associated with intracerebral hemorrhage after thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke: pooled analysis of placebo data from the Menon y cols. Puntuación de riesgo de hemorragia intracraneal en pacientes con ictus isquémico agudo 129 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. Stroke-Acute Ischemic NXY Treatment (SAINT) I and SAINT II trials. Stroke. 2009;40:3067–3072. Demchuk AM, Morgenstern LB, Krieger DW, Linda Chi T, Hu W, Wein TH, et al. Serum glucose level and diabetes predict tissue plasminogen activator-related intracerebral hemorrhage in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 1999;30:34 –39. Nadeau JO, Shi S, Fang J, Kapral MK, Richards JA, Silver FL, et al. tPA use for stroke in the registry of the Canadian Stroke Network. Can J Neurol Sci. 2005;32:433– 439. Wahlgren N, Ahmed N, Davalos A, Ford GA, Grond M, Hacke W, et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase for acute ischaemic stroke in the Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis in Stroke-Monitoring Study (SITS-MOST): an observational study. Lancet. 2007;369:275–282. Wahlgren N, Ahmed N, Eriksson N, Aichner F, Bluhmki E, Davalos A, et al. Multivariable analysis of outcome predictors and adjustment of main outcome results to baseline data profile in randomized controlled trials: Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis in Stroke-Monitoring Study (SITS-MOST). Stroke. 2008;39:3316 –3322. Reeves MJ, Fonarow GC, Smith EE, Pan W, Olson D, Hernandez AF, et al. Representativeness of the Get With The Guidelines–Stroke registry: comparison of patient and hospital characteristics among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2012;43:44 – 49. Cucchiara B, Kasner S, Tanne D, Levine S, Demchuk A, Messe S, et al. Validation assessment of risk scores to predict postthrombolysis intracerebral haemorrhage. Int J Stroke. 2011;6:109 –111. Tsivgoulis G, Saqqur M, Barreto A, Demchuk AM, Ribo M, Rubiera M, et al. Validity of hat score for predicting symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage in acute stroke patients with proximal occlusions: data from randomized trials of sonothrombolysis. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;31:471–476. Cook NR. Use and misuse of the receiver operating characteristic curve in risk prediction. Circulation. 2007;115:928 –935. Sylaja PN, Cote R, Buchan AM, Hill MD. Thrombolysis in patients older than 80 years with acute ischaemic stroke: Canadian alteplase 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. for stroke effectiveness study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006; 77:826 – 829. Tsivgoulis G, Frey JL, Flaster M, Sharma VK, Lao AY, Hoover SL, et al. Pre-tissue plasminogen activator blood pressure levels and risk of symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2009;40:3631–3634. Ahmed N, Wahlgren N, Brainin M, Castillo J, Ford GA, Kaste M, et al. Relationship of blood pressure, antihypertensive therapy, and outcome in ischemic stroke treated with intravenous thrombolysis: Retrospective analysis from Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis in StrokeInternational Stroke Thrombolysis Register (SITS-ISTR). Stroke. 2009; 40:2442–2449. Prabhakaran S, Rivolta J, Vieira JR, Rincon F, Stillman J, Marshall RS. Symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage among eligible warfarin-treated patients receiving intravenous tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:559 –563. Seet RC, Zhang Y, Moore SA, Wijdicks EF, Rabinstein AA. Subtherapeutic international normalized ratio in warfarin-treated patients increases the risk for symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage after intravenous thrombolysis. Stroke. 2011;42:2333–2335. Vergouwen MD, Casaubon LK, Swartz RH, Fang J, Stamplecoski M, Kapral MK. Subtherapeutic warfarin is not associated with increased hemorrhage rates in ischemic strokes treated with tissue plasminogen activator. Stroke. 2011;42:1041–1045. Hermann A, Dzialowski I, Koch R, Gahn G. Combined anti-platelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel: risk factor for thrombolysis-related intracerebral hemorrhage in acute ischemic stroke? J Neurol Sci. 2009; 284:155–157. Hacke W, Kaste M, Fieschi C, von Kummer R, Davalos A, Meier D, et al. Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial of thrombolytic therapy with intravenous alteplase in acute ischaemic stroke (ECASS II). Second European-Australasian Acute Stroke Study investigators. Lancet. 1998;352:1245–1251. Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by Springer Healthcare on September 13, 2012