factors responsible for the presence and distribution of

Anuncio

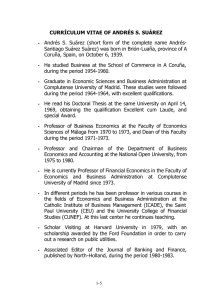

Ardeola 54(2), 2007, 205-215 FACTORS RESPONSIBLE FOR THE PRESENCE AND DISTRIBUTION OF BLACK-BELLIED SANDGROUSE PTEROCLES ORIENTALIS IN THE NATURE PARK “VALE DO GUADIANA” Ana Cristina CARDOSO* 1, Ana Sofia POEIRAS** and Carlos CARRAPATO*** SUMMARY.—Factors responsible for the presence and distribution of black bellied sandgrouse Pterocles orientalis in the Natura Park “Vale do Guadiana”. Aims: Identify factors that are responsible for the presence and distribution of black-bellied sandgrouse in the nature park of ‘Vale do Guadiana’ so that management actions can be undertaken. Localization: Southern Portugal. Methods: Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric tests and Bailey’s tests was used to analyse the preferences among biotopes, while logistic regression analysis was utilized to obtain an explanation model for species distributions during breeding and non-breeding seasons. Variables considered in the analysis included presence or absence of cattle; ground vegetation coverage, height and vertical density; tree density; bush coverage; slope exposition; stone coverage and number of stones; wind direction; habitat; soil capacity; distance to roads, drinking places and villages; and altitude. Results: The results of biotope selection indicated that sandgrouses preferred fields of leguminous plants during both breeding and non-breeding periods and tillage during the breeding period. Montado and fallows older than two years were avoided during the non-breeding season. Cereal fields were used according to their availability. Besides not significantly, fallows were highly used. For the explanation model, six variables that explain the species distribution during the breeding season were selected: cattle presence, stony ground and distance to secondary roads had a positive effect, while vegetation cover, stone cover and distance to the drinking places had a negative effect. During the non-breeding period, the model was not adjusted to validation sample. Conclusions: It was found that the most important biotopes are leguminous cultivations and fallows with extensive pastures. Grazing can have either a positive or a negative effect on these fields, depending on cattle density. Besides the number of small dams, drinking places are still a limiting factor for this species. Dispersion of settlements and roads is also negative to sandgrouse distribution. Finally conservation implications, namely management actions such as an enlargement of leguminous fields, cattle grazing control and modifications of Territory Management Plans, are discussed. Key words: habitat selection; logistic regression; management actions; Pterocles orientalis; seasonal variation. RESUMEN.—Factores responsables de la presencia y distribución de la ganga ortega Pterocles orientalis en el Parque Natural “Vale do Guadiana”. * Parque Natural do Vale do Guadiana, Apartado 45, 7750-352 Mértola, Portugal. ** Bairro do Bacelo, Rua dos Altos, nº 6, 7000-693 Évora, Portugal. *** Parque Natural do Vale do Guadiana, Apartado 45, 7750-352 Mértola, Portugal. 1 Corresponding author: mertolaana@gmail.com 206 CARDOSO, A. C., POEIRAS, A. S. and CARRAPATO, C. Objetivos: Identificar los factores que son los responsables de la presencia y distribución de la ganga ortega Pterocles orientalis en el Parque Natural “Vale do Guadiana” para que las acciones de manejo y conservación puedan ser adoptadas. Localización: Sur de Portugal. Métodos: Pruebas no paramétricas de Kruskal-Wallis y de Bailey se utilizaron para analizar las preferencias entre biotopos, mientras que regresiones logísticas lo fueron para obtener modelos que explicaran la distribución de la especie durante el periodo reproductor y durante el resto del año. Las variables que se incluyeron en los análisis fueron: presencia de ganado vacuno, cobertura vegetal, altura y densidad vertical, densidad del arbolado, cobertura arbustiva, pendiente, cobertura de rocas y su número, dirección del viento, hábitat, capacidad del suelo, distancias a carreteras, bebederos y pueblos, y la altitud. Resultados: Se muestra que las gangas ortega seleccionan campos de leguminosas durante todo el año y campos labrados durante el periodo reproductor. Montado y barbechos de más de dos años son evitados durante el periodo no reproductor, mientras que los campos con cereales eran utilizados de acuerdo a su disponibilidad. A pesar de ser un resultado no significativo, los barbechos eran altamente utilizados. En el modelo explicativo fueron seis las variables que explicaban la distribución de la especie durante el periodo reproductor: presencia de ganado vacuno, presencia de rocas, y la distancia a carreteras secundarias tenían un efecto positivo, mientras que la cobertura vegetal, la cobertura de rocas y la distancia a bebederos tenían un efecto negativo. Durante el periodo no reproductor, el modelo final no fue adecuado. Conclusiones: El trabajo muestra que el biotopo más importante para esta especie y en el área de estudio fueron los campos de leguminosas y los barbechos con extensos pastos. La presencia de ganado puede ser tanto positiva o negativa, dependiendo de la densidad de cabezas vacunas. A pesar del bajo número de zonas con agua, los bebederos son un factor limitante para esta especie. La fragmentación del hábitat y las carreteras actúan de forma negativa. Finalmente, se discute las implicaciones en la conservación de la especie que tendrían el aumento de los campos de leguminosas, el control del tamaño del ganado vacuno y las modificaciones en los planes de manejo del territorio. Palabras clave: selección de hábitat; regresión logística; acciones de manejo, Pterocles orientalis; variación estacional. INTRODUCTION Steppe-land birds are one of the most endangered groups of species in the world, especially in developed countries (Bota et al., 2005). The black-bellied sandgrouse Pterocles orientalis is a steppe-land species whose distribution in Europe is limited mainly to Turkey and the Iberian Peninsula (Cramp and Simmons, 1983; Tucker and Heath, 1994; De Juana, 1999). Major changes in EU Common Agriculture Policy have occurred in the last few decades, causing significant alterations in agricultural and grassland habitats (Tucker and Evans, 1997; Donald et al., 2001). The black-bellied sandgrouse European population has suffered a clear decline in the last thirty years mainly Ardeola 54(2), 2007, 205-215 due to changes in agricultural practices and the loss of habitat (Tucker and Heath, 1994). There are no more than 300 individuals in Portugal - a reason why the bird has an unfavourable status ‘Endangered’ in Portugal (Almeida et al., 2005). The European population is classified as ‘Vulnerable’, and it is listed as SPEC 3 – a species whose global populations are not concentrated in Europe, but which has an unfavourable status in Europe (Tucker and Heath, 1994). In Portugal, the main threat to steppe-land birds is the abandonment of traditional farming and replacement by intensive agriculture or forestation (Moreira et al., 2004; Silva et al., 2004; Pinto et al., 2005). In southern Portugal since the launch of wheat campaign, agriculture has been supported by European Union BLACK-BELLIED SANDGROUSE IN THE NATURE PARK “VALE DO GUADIANA” subsidies. Actually, abandonment of land due to the soil depletion and forestation, which is also funded by the European Union, can be negative to steppe-land birds. The objective of this study was to collect information on the ecology of the black-bellied sandgrouse that could be used to support management measures in a nature park. In particular, there was a focus on evaluating habitat use and understanding the role of habitat characteristics in determining the sandgrouse distribution in the nature park of ‘Vale do Guadiana’. MATERIAL AND METHODS Study area The study took place in an area of 24000 ha in the nature park of ‘Vale do Guadiana’ (total area: 70000 ha; 37º42’ N 07º39’ W). The park is also a Special Protection Area under Birds Directive CE/79/409. The region is under Mediterranean influence, with hot summers and cold and rainy winters. Average annual rainfall is 455 mm. The area is crossed by the Guadiana River and includes hills and plains, cultivated areas, fallows and cereal fields, scrubland and open woodland. Cereal cultivation follows traditionally a cycle of 3 9 years: wheat (1st year), oats or barley (2nd year) and fallow (3rd to 9th years). Older fallows are occupied by shrubs, mostly cistus, Cistus ladanifer. Data collection The population of black-bellied sandgrouse living in the nature park has been previously estimated at ca. 80 individuals (Cardoso and Carrapato, 2002). Because of the species’ secretive habits, small population size and mostly open landscape, it was decided to survey all the open areas to identify presence points of 207 the species. Fieldwork was carried out between April 2002 and March 2003. During the non-breeding period (October May), the study area was intensively surveyed for two days once a month. The whole study area was visited by car and by foot. Each flock or isolated bird detected at the ground was defined as a presence point. Drinking places and flying birds were not considered in the analysis. During the breeding period (June - September), observation of black-bellied sandgrouse was difficult because the birds stayed in couples, choosing and occupying breeding places. With the purpose of finding breeding and feeding areas, observation points were selected near drinking places, where departure and arrival directions of the birds could be recorded and their point of origin and destination estimated. Later, these areas were explored more intensively by foot. During this season, field work lasted for four consecutive mornings each month due to hot temperatures. The main biotopes were mapped at different periods: spring - summer and autumn - winter (Table 1). Absence points were marked on the corners of a 1 x 1 Km UTM system map. These were later visited in the field and took the same variables rather than the presence points. The same number of observations for presences and absences were used: 50 for the breeding period and 45 for the non-breeding-period. Nineteen variables were included in the initial logistic regression model (Table 2). Biotope composition was determined using a 1 000-m buffer and Table 1 shows the classification. Coordinates of measuring points were taken with an error rate of 3-12 meters using a GPS. A 50 cm x 50 cm square area was used to measure vegetation and stone coverage and number. Vegetation vertical density was measured by using a vegetation profile board (a 100 cm x 32 cm plate, with black and white stripes of 12.5-cm width; adapted from Hays et al., 1981). These variables were measured in 5 replicates: one in the centre and 4 located 10 meters away from the centre in different directions. Inclination was Ardeola 54(2), 2007, 205-215 208 CARDOSO, A. C., POEIRAS, A. S. and CARRAPATO, C. TABLE 1 Main types of biotopes in the study area. [Principales biotopos en el área de estudio.] Biotope Code Description Tillage Leguminous cultivations TILL LEGU Cereal fields Brushwood CERE BRUS Montados MON Fallows FALL Old-fallows FALO Naked soil, mostly without vegetation Cultivation of: chickpea, yellow-lupin, common vetch, hairy vetch and subterranean clover. Fields of wheat, oats or barley Bushy ground occupied by: cistus Cistus ladanifer, sargasso Cistus monspeliensis, rock-rose Cistus crispus, Cistus salvifolius, french lavander Lavandula stoechas or dwarf furze Genista triacanthos. Very open woodland of holm-oak Quercus rotundifolia, also used as pasture or for cereal cultivation Cereal fallows with one or two years, with herbaceous coverage and some stony areas; usually used as pastures Cereal fallows with more than two years, usually colonized by some bushes measured as described in Hays et al. (1981). Soil capacity was classified from 1 (good quality) to 6 (poor quality) according to soil capability maps for agricultural use. Distances were calculated with the help of aerial photographs and Spatial Analyst of ArcView 3.1. Statistical analysis Habitat selection was analysed by comparing the use of each biotope with its availability in the study area. Biotope use was defined as the percentage of presences in each biotope. Biotope availability was defined as the percentage occupied by each type of habitat in the study area. Whether sandgrouse were using habitats according to their availability was tested with Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test (Zar, 1996). Positive and negative selections were analysed with Ivlev’s Electivity Index (Jacobs, 1974) and their significance was tested using Bailey’s tests (Cherry, 1996). Ardeola 54(2), 2007, 205-215 A univariate analysis was performed for each of the nineteen variables, by measuring their association with the response variable, according to the results of Wald and G (maximum likelihood ratio) tests (Hosmer and Lemeshow, 1989). In multivariate analysis, variables were ranked according to the results of the statistical tests used previously. Then a forward stepwise elimination process was applied, in which all variables with a P > 0.05 in the Wald test and those where the odds ratio estimation (95 % confidence) included value 1 were removed from the model (Hosmer and Lemeshow, 1989). To assess the fit of the model, we used the Pearson chi-square and classification table (Hosmer and Lemeshow, 1989). RESULTS Habitat selection: biotope types Habitat use of sandgrouse differed significantly from random (χ2 = 9.49; P < 0.001). BLACK-BELLIED SANDGROUSE IN THE NATURE PARK “VALE DO GUADIANA” 209 TABLE 2 Variables that entered in the initial logistic regression model to analysing the presence/absence of blackbellied sandgrouse. [Variables que se utilizaron en la regresión logística para analizar la presencia/ausencia de gangas ortega.] Variable Code Description of the variable Units Wind direction Cattle Vegetation height Vegetation coverage Vertical density Tree density Coverage of shrubs Inclination Slope exposure Stone coverage Number of stones Distance to the villages WIND CATT VEGH VEGC VEGP TREN SHRC INCL SLEX STOC STON DVIL Wind direction at the time of observation Cattle presence or absence Vegetation height Vegetation coverage Vegetation cover at different heights Number of trees within a 50 m radius Proportion of shrubs within a 50 meters radius Ground inclination Exposure to the sun Proportion of ground covered with stones Number of stones Distance to the nearest village (settlement with more than 100 inhabitants) Distance to the nearest rural agglomerates (settlement with less than 100 inhabitants) Distance to the nearest monte - small group of rural houses that belongs to the same family; typical structure of Alentejo Distance to the nearest drinking place Distance to the nearest main road – national roads Distance to the nearest secondary road, asphalted (municipal roads) or not asphalted Soil capacity to agriculture and forest 1–4 0/1 M m2 % Distance to rural agglomerates DRAG Distance to montes DMON Distance to drinking places Distance to main roads Distance to secondary roads DRNK ROAM ROAS Soil Capacity SOIL During the breeding period, sandgrouse preferred leguminous cultivations and tillage (Table 3). Crops and fallow were apparently used according to their availability. Fallow was the most used biotope, and it was also the most easily available (Fig. 1). Old fallows were used only during the breeding period (Table 3 and Fig. 1). The observations at this habitat type were made at artificial feeding places developed by hunters to attract partridges and pigeons during this period. Usually these spots have an area of 20 x 50 sq. m. The land is ploughed and a large amount of seeds (mainly wheat, oats and bar- 0-1 0-45º 1-4 m2 m m m m m m 1-6 ley) is spread. A nest of black-bellied sandgrouse was found close to one of these spots. During non-breeding period, only leguminous cultivated areas were chosen (Table 3). Habitat selection: habitat variables Table 4 shows the results of the univariate analysis, for the variables with P-value less than 0.05 in the Wald test. All the variables with significant P-values in the univariate analysis were included in the initial logistic regression model. While assessArdeola 54(2), 2007, 205-215 210 CARDOSO, A. C., POEIRAS, A. S. and CARRAPATO, C. TABLE 3 Habitat selection analysis using Ivlev and Bailey tests. Ns: non significant result; (+) positive selection; (-) negative selection (CERE: cereal fields; LEGU: leguminous cultivation; TILL: tillage; MONT: montado; FALL: fallow; FALO: old-fallow). [Analysis de selección de hábitat usando las pruebas de Bailey e Ivlev. Ns: resultado no significativo; (+) selección positiva; (-) selección negativa.] Breeding period Non-breeding period Biotope Ivlev Bailey Selection Ivlev Bailey Selection CERE LEGU TILL MONT FALL FALO 0.219 0.872 0.652 -1 0.045 - 0.237 [0.041; 0.297] [0.051; 0.319] [0.027; 0.252] [- ; 0.086] [0.234; 0.586] [0.062; 0.340] ns + + ns ns - 0.027 0.922 0.544 -1 0.358 -1 [0.018; 0.273] [0.105; 0.452] [5x10-5-; 0.181] [- ; 0.104] [0.37; 0.761] [- ; 0.104] ns + ns ns - FIG. 1.—Availability versus use of different biotopes by sandgrouses (CERE – cereal fields; LEGU- leguminous cultivation; TILL - tillage; MON - montados ; FALL- fallow ; FALO - old fallows). [Disponibilidad frente a uso de diferentes biotopos por la ganga ortega en Portugal.] ing the linearity of the variables, the square root transformation of variable STOC was included in the model (Table 5). The final model is adjusted effectively to the data and to the validation sample during the breeding period (Table 6). During the nonbreeding period, the model is adjusted to the data but not to validation sample. In fact, this season is longer than the other one and land use suffers a lot of transformation. The heteroArdeola 54(2), 2007, 205-215 geneity of this period can explain the inadaptability of the model. DISCUSSION Habitat selection: biotope types At the nature park though the leguminous cultivations are rare, they are of major impor- 211 BLACK-BELLIED SANDGROUSE IN THE NATURE PARK “VALE DO GUADIANA” TABLE 4 Variables with significant differences (P < 0.05) in the univariate analysis (VEGC – vegetation cover; STON - number of stones; DRNK - distance to drinking places; ROAS - distance to secondary roads; DRAG -distance to rural agglomerates; SLEX - slope exposure; LEGU - leguminous cultivation; CATT - cattle; VEGH - vegetation heigh; BRUS - brushwood; TREN - tree density; FALL - fallow; STOC - stone cover; TILL - tillage; DVIL - distance to the villages; INCL - inclination; SHRC - coverage of shrubs; SOIL - soil capacity). [Variables con diferencias significativas (P < 0.05) en los análisis univariantes (véase texto).] Breeding period Non-breeding period Variables P G-test Relationship with the response variable P G-test Relationship with the response variable VEGC STON DRNK sqrtROAS logDRAG SLEX LEGU CATT VEGH BRUS TREN FALL STOC TILL logDVIL INCL SHRC SOIL < 0.001 < 0.001 < 0.001 < 0.001 < 0.001 0.004 0.003 0.010 0.013 0.014 0.016 0.030 0.031 50.24 27.50 18.97 18.62 15.48 13.18 8.64 6.63 6.11 5.99 5.80 4.71 4.66 + + + + + + + - < 0.001 0.001 < 0.001 0.038 0.009 24.50 11.78 32.50 4.29 6.79 + + + < 0.001 13.00 + 0.076 0.002 0.003 3.15 9.88 8.84 - 0.001 0.001 0.016 0.024 0.030 0.029 11.99 10.11 5.76 5.07 4.70 4.78 + + + - tance to sandgrouse in both periods. In Spain, besides Extremadura, black-bellied sandgrouse does not use or select leguminous fields (Suárez et al., 1999a). From a reading of works of different authors (Martínez, 1994; Barros et al.,1996; Suárez et al., 1999a; Moreira et al., 2004; Silva et al., 2004), it is understood that leguminous fields are not quite equal and in the majority of the cases the authors do not classify them; they can be either alfalfa or broccoli fields, which can be used by little bustard Tetrax tetrax, but not by sandgrouses. Moreover, stomach contents of the sandgrouse show that leguminous plants were very important (Suárez et al. 1999b). This preference is probably explained by their high nutritive value and digestibility (Jarrigue, 1981; Abreu et al., 2000). The use of tillage during breeding season may be related with reproduction, because this type of ground coverage can provide better camouflage for adults and chicks (Barros et al., 1996). In fact, some nests were found in this biotope (pers. obs.). Ardeola 54(2), 2007, 205-215 212 CARDOSO, A. C., POEIRAS, A. S. and CARRAPATO, C. TABLE 5 Coefficients and P-value of different variables in the logistic regression model for habitat selection of black-bellied sandgrouse in the breeding and non-breeding periods. [Coeficientes y valores de probabilidad para las diferentes variables introducidas en la regresión logística para caracterizar la selección de hábitat de la ganga ortega en el periodo reproductor o no.] Breeding period Variable Constant CATT VEGC Sqrt STOC STON ROAS DRNK TREN STOC G-test Non-breeding period Coefficient P 2.076 4.801 -0.083 -0.712 1,293 0.004 -0.002 0.254 0.015 0.014 0.053 2.351 0.058 0.070 75.617 Coefficient P -0.204 0.009 -0.003 -0.340 -0.244 67.949 0.013 0.055 0.024 TABLE 6 Classification rates of correct presences (CP), correct absences (CA) and overall correct classification ((CP+CA)/CT), considering a cut-off point of 0.5. [Tasas de clasificación como presencia correcta (CP), ausencia correcta (CA) y clasificación correcta general ((CP+CA)/CT), considerando un punto de corte de 0,5.] Breeding period Classification rates CP CA CT χ2 Pearson Model sample Validation sample 0.97 0.91 0.94 21.69 (d = 63) 0.93 1 0.96 6.63 (d = 23) Crops were used in two different periods: after sowing during non-breeding season and stubble during breeding season. During both periods, birds can easily find seeds to feed on (Barros et al., 1996). This is very important to the diet of these birds as Suárez et al. (1999b) have reported. We also observed them eating Ardeola 54(2), 2007, 205-215 Non-breeding period Model sample Validation sample 0.94 0.94 0.94 20.95 (d = 58) 0.69 0.88 0.78 39.94 (d = 22) soft leaves from sprouts at newly sown fields. The annual agriculture cycle dynamic is important to these birds once they can find easily seeds during late autumn and summer when availability of seeds from natural vegetation is low. Fallow land was also frequently used (Fig. 1). This can be explained by the presence of BLACK-BELLIED SANDGROUSE IN THE NATURE PARK “VALE DO GUADIANA” grazed low vegetation that promotes an efficient vigil (Barros et al., 1996) and easier progress in the field. Fallow presents the highest floristic diversity (unpub. data), and so more opportunities to feed on different kind of seeds. Otherwise, there is a predominance of pioneer species producing abundant seeds (Fenner, 1985). This is especially relevant in cultivated areas that are characterized by their structural simplicity and by the poverty of natural vegetation due to agriculture (Martínez, 1994). Montado was never used by sandgrouse. In fact, wooded or forested habitats have reduced use or are of no use to sandgrouse (Barros et al., 1996; Suárez et al., 1999a) - a fact that could be related to lack of visibility. Ferns and Hinsley (1995) verified that the amount of ground not visible to drinking sandgrouse surrounding each water hole was the most important factor influencing the birds’ choice. The trees in the montados may have a similar effect by hiding potential predators. Habitat selection: habitat variables Vegetation coverage seems to be a very important component in the habitat selection by black-bellied sandgrouse, mainly during the breeding season, due to its influence on one of the basic requirements of this species - visibility (Ferns and Hinsley, 1995). On the other hand, cattle presence is an important factor as it influences vegetation coverage. Nevertheless, overgrazing can be unfavourable to this species as happens in Extremadura, Spain (Suárez et al., 1999c). According to the logistic regression model applied, sandgrouse prefer areas with reduced stone coverage but it is positively related with stone number. It is believed that such an amount of stones is related to the soil capacity. In the majority of the study area, the layer of fertile soil is very thin and stony. This type of agricultural soil needs long fallows, and this is the biotope that sandgrouse mostly used. On the 213 other hand, stony ground can provide good camouflage for adults and chicks. The model has only chosen one of the disturbance factors. During the breeding season, sandgrouse avoided secondary roads. This negative relation was also reported by Rocha (pers. obs.) between great bustards Otis tarda and both secondary and main roads. Silva et al. (2004) found that the little bustard avoids the proximity of roads and inhabited houses. Univariate analyses also indicated that sandgrouse avoided the vicinity of villages, rural agglomerates and montes in different seasons (Table 4). Besides the number of small dams (majority less than 4000 m2) used by cattle in study area, the model revealed drinking place distribution as a limiting factor. In fact, this species needs to drink regularly. Parental expenditure is greatest during breeding period. The role of males as water carriers increased their energy expenditure and decreased their time available for foraging (Hinsley and Ferns, 1994). Distances between feeding areas, brood and drinking places and flight time are determinant to the energy budget (Hinsley and Ferns, 1994); hence, a good net of water holes is a determinant for the presence of species. The most important drinking places in the present study area were a dam (2000 m2) in the middle of the study area in a pine forestation of c. 6/7 years growth, and a part of the Chança dam (a Spanish dam of more than 9 Km2) near one reproduction area (Cardoso and Carrapato, 2002). Conservation and management implications In conclusion, agricultural environment seems to provide suitable biotopes for sandgrouse as was reported by other authors (Barros et al., 1996; Suárez et al., 1999a). It has been shown that the most important biotopes are leguminous cultivations and fallows with extensive pastures. It is suggested that the nature park should promote agricultural mosaic and especially increase Ardeola 54(2), 2007, 205-215 214 CARDOSO, A. C., POEIRAS, A. S. and CARRAPATO, C. the relative proportion of these two biotopes. Nowadays, agriculture subsidies for forestation and wheat cultivation are higher than those for leguminous or for extensive pastures (fallow). The nature park must develop appropriate mechanisms to reverse these facts. Extensive pasture has an important role in controlling vegetation and giving economic advantage to fallows. In a certain way, it can delay agriculture intensification or abandonment if sheep market value does not fall. Even sheep production, for example, for making cheese, could be of negative conservation interest in the short term. Increase of production will be followed by the implementation of irrigated cultures, such as sorghum, and it will be of negative value to sandgrouse and other steppe-land birds. Cattle density is the determinant factor in achieving proper habitat availability for sandgrouse. This can be attained by implementing a Good Practice Agriculture Code adaptable to the soil poverty of this region. Finally, Territory Management Plans must take into account the results of disturbance factors. It is the opinion of the authors that the existence of large concentrated settlements is more favourable to sandgrouse than several dispersed small agglomerations of houses. This fact will also contribute to reducing the need for roads. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.—We thank Prof. Teresa Batista and Doctor José Carlos Brito for their valuable help in GIS and statistics analysis, respectively. We also thank Célia Medeiros and Teresa Silva for help in collecting field data. This study was supported logistically and co-funded by Instituto da Conservação da Natureza and FAUNATRANS - INTERREG project. BIBLIOGRAPHY ABREU, J. M., BRUNO-SOARES, A. M. and CALOURO, F., 2000. Intake and nutritive value of mediterranean forages and diets, 20 years of experiArdeola 54(2), 2007, 205-215 mental data. Instituto Superior de Agronomia, Universidade Técnica de Lisboa. Laboratório Químico Agrícola Rebelo da Silva. Lisboa. ALMEIDA, J., (coord), CATRY, P., ENCARNAÇÃO, V., FRANCO C., GRANADEIRO J. P.; LOPES R., MOREIRA F., OLIVEIRA P., ONOFRE N., PACHECO C., PINTO M., PITTA GROZ M. J., RAMOS J. and SILVA L. 2005. Pterocles orientalis Cortiçol-de-barriga-preta. In: M. J. Cabral, J. Almeida, P. R. Almeida, T. Dellinger, N. Ferrand de Almeida, M. E. Oliveira, J. M. Palmeirim, A. I. Queiroz, L. Rogado and S. Reis (Eds.): Livro Vermelho dos Vertebrados de Portugal, pp. 321 - 322. Instituto da Conservação da Natureza. Lisboa. BARROS, C., BORBÓN, M. N. and DE JUANA, E., 1996. Selección de Hábitat del Alcaraván (Burhinus oedicnemus), la Ganga (Pterocles alchata) y la Ortega (Pterocles orientalis) en pastizales y cultivos de La Serena (Badajoz, España). In: J. Fernández Gutiérrez and J. Sanz-Zuasti (Eds.): Conservación de las Aves Estepárias y su Hábitat, pp. 221 - 228. Junta de Castilla y León, Valladolid. B OTA , J., M O R A L E S , M. B., M A Ñ O S A , S. and CAMPRODON, J., 2005. Ecology and Conservation of Steppe-land birds. Lynx Ediciones and Centre Tecnològic Florestal de Catalunya, Barcelona. CARDOSO, A. C. and CARRAPATO C., 2002. Breves Notas sobre o Cortiçol-de-barriga-preta Pterocles orientalis no Parque Natural do Vale do Guadiana. Airo, 2: 113-116. CHERRY, S., 1996. A comparison of confidence interval methods for habitat use-availability studies. Journal of Wildlife Management, 60: 653658. DONALD, P. F., GREEN, R. E. and HEATH, M. F., 2001. Agricultural intensification and the collapse of Europe’s farmland bird populations. Proceedings of the Royal Society London, B 268: 25-29. FENNER, M., 1995. Seed ecology. Chapman and Hall. London. FERNS, P. N. and HINSLEY, S. A., 1995. Importance of topography in the selection of drinking sites by sandgrouse. Functional Ecology, 9: 371375. HAYS, R. L., SUMMERS, C. and SEITZ, W. 1981. Estimating wildlife habitat variables. U.S.D.I. Fish and Wildlife Service. FWOS/OBS-81/47. BLACK-BELLIED SANDGROUSE IN THE NATURE PARK “VALE DO GUADIANA” HINSLEY, S. A. and FERNS, P. N., 1994. Time and energy budgets of breeding males and females in sandgrouse Pterocles species. Ibis, 136: 261-270. HOSMER, D. W. and LEMESHOW, S., 1989. Applied Logistic Regression. John Wiley and Sons, New York. JACOBS, J., 1974. Quantitative Measurement of Food Selection - A Modification of the Forage Ratio and Ivlev’s Electivity Index. Oecologia, 96: 413417. JARRIGUE, R., 1981. Alimentación de los ruminates. Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique, Mundi-Prensa, Madrid. MARTÍNEZ, C., 1994. Habitat selection by the little bustard Tetrax tetrax in cultivated areas of central Spain. Biological Conservation, 67: 125-128. MOREIRA F., MORGADO, R. and ARTHUR, S., 2004. Great bustard Otis tarda habitat selection in relation to agricultural use in southern Portugal. Wildlife Biology, 10: 4. PINTO, M., ROCHA, P. and MOREIRA, F., 2005. Longter m trends in g reat bustard (Otis tarda) populations in Portugal suggest concentration in single high quality area. Biological Conservation, 124: 415-423. SILVA, J. P., PINTO, M. and PALMEIRIM, J. M., 2004. Managing landscapes for the little bustard Tetrax tetrax: lessons from the study of winter habitat selection. Biological Conservation, 117: 521-528. SUÁREZ, F., HERRANZ, J., MARTÍNEZ, C., MANRIQUE, J., ASTRAIN, C., ETXEBERRIA, A., CURCO, A., ESTRADA, J. and YANES, M. 1999a. Utilización y selección de hábitat de las gangas ibérica y ortega en la península ibérica. In: J. Herranz, and F. Suárez: La Ganga Ibérica (Pterocles alchata) y la Ganga Ortega (Pterocles orientalis) en España, pp. 127-156. Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, Organismo Autónomo Parques Nacionales. SUÁREZ, F., HERVÁS, I., LEVASSOR, C. and CASADO, M. A. 1999b. La alimentación de la ganga ibérica y la ganga ortega. En: J. Herranz and F. Suárez: La Ganga Ibérica (Pterocles alchata) y la Ganga Ortega (Pterocles orientalis) en España, 215 pp. 215-229. Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, Organismo Autónomo Parques Nacionales. SUÁREZ, F., OÑATE, J. J. and HERRANZ, J. 1999c. Estado y problemática de conservación de las gangas ibérica y ortega en España. En: J. Herranz and F. Suárez: La Ganga Ibérica (Pterocles alchata) y la Ganga Ortega (Pterocles orientalis) en España, pp. 273-302. Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, Organismo Autónomo Parques Nacionales. TUCKER, G. M. and EVANS, M. I. 1997. Habitats for birds in Europe: a Conservation Strategy for the Wider Environment. BirdLife Conservation Series No.6, Cambridge, UK, BirdLife International. TUCKER, G. M. and HEATH, M. F., (Eds), 1994. Birds in Europe: Their Conservation Status. BirdLife Conservation Series No. 3. Cambridge, UK: BirdLife International. ZAR, J. H. 1984. Biostatical Analysis. Prentice-Hall. New Jersey. [Recibido: 20-12-06] [Aceptado: 28-09-07] Ana Cristina Cardoso is a biologist, pos/graduated on Management and Environmental Politics who have been working on Nature Park, studying the ecology of black-bellied sandgrouse populations, also coordinate the national census of black-bellied sandgrouse and pin-tailed sandgrouse, is also co-author of Portuguese steppe-land birds Action Plan. At present is doing her master thesis on incentive measures for conservation of steppeland species. Ana Sofia Poeiras is licensed on Environment Sciences, and did this work to obtain the degree of licentiate. Actually, is working with GIS at several institutions. Carlos Carrapato is a nature vigilant and photographer, helping several biologists in the field work, mainly with steppe-land species. Developed and tried several methods to capture sandgrouses, and spending a lot of time studying their behaviour at drinking places. Ardeola 54(2), 2007, 205-215