pax romana - Universidad de Granada

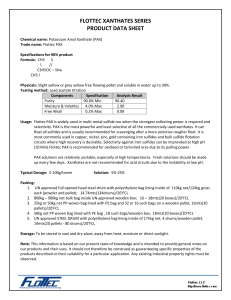

Anuncio

PAX ROMANA MUÑOZ, Francisco A. Pax (stem pac-) is the Latin feminine noun from which the English word “peace” is derived. The Latin word comes from the Indo-European root pak-/pag-, which meant “fasten, fix” (as in the setting up of a post to mark a land boundary) and to settle by convention, to reach an agreement between two parties”. Pax has numerous meanings: the reaching of agreement between two parties; pact; agreement; peace; respect for others; quality of life; friendship; peaceful time; peace in death; mental tranquility; calmness; equity; civil safety and security; god; and the imperturbability of the gods. It is a term used by nearly all the great Roman writers, all of whom use the term pax for various practices engaged in by Roman society through which conflicts were regulated in a peaceful manner. The Roman people's ideas of peace were influenced by their experience in the early years of the Republic, through the relations established with other people of the Italian peninsula and the Mediterranean basin, and, in particular, with the Greek tradition that put them in contact with different theories and practices used in the regulation and management of relationships between conflicting groups. Quality of Life and Well-Being Pax in its sense of quality of life could be expressed by a greeting. It is a person's intrinsic quality that is shared with his or her fellows, and its presence is reinforced through an expressive ritual, in which people wish each other good health, well-being, and personal, family, and agreement. Through pax it is possible to achieve well-being and to save personal and social energy when suffering injury or when destruction of the land or cities occurs. Pax helps define the relationship between people by means of expressions which give it a sincere human, affective meaning, and it is reinforced through relations with other virtues like love and friendship. Pax is often depicted as a feminine virtue, and the goddess Pax is intimately tied to the idea of reproduction of life (maternity, education, domestic work). The relation of pax with the gods is a clue to its pervasiveness in Roman activities, both private and public. The gods themselves must possess a serene everlasting life with profound peace, detached from worldly matters, to guide humans in achieving good conduct. Prayer is necessary; through it, the gods are begged to intercede in the attainment of desired peacefulness. To this end, the role of the goddess Pax is assisted by the other gods. Likewise, the Roman people's interest in peace is reflected in many Latin aphorisms, such as Nihil tam populare quam pacem (Nothing is a popular as peace). Peace is pleasant and desired by all; it means unity, tranquility, and dignity for the res publica (the state). Pax is supported by all the different social groups that see its immediate benefits or that are affected by war (e.g., farmers, tradesmen, women). Facing Violence Throughout the Republic and the Empire, pax as intended to strengthen the political regime and social harmony between the state and its citizens, the assemblies, and the Senate. Good rulers were supposed to promote a pax guaranteed by the state and the laws and to avoid civil war or wars with foreign nations. The emperor Augustus was an outstanding example: He succeeded in pacifying (defeating, negotiating, and reaching agreements with) all his internal adversaries and external enemies. The Pax Romana he attained meant a breakthrough in the conception of the Roman state. With it, conquests were consolidated and the promotion of further wars was significantly curtailed. Because the emperor was its direct promoter, his relationship with pax was a sign of his power; when granted an official character, pax became a matter of public interest for the whole state. The expression pax ac bello is used frequently in Roman literature, where it defines the dialectical relationship between war and peace. The Roman state, the Senate, the social institutions, the people, all yearned for lasting peace, despite the fact that they did occasionally benefit from war. In countless texts, pax appears in connection with the army as an executive institution of war and at the same time as an institution seeding peace. War is something at once possible and desired. In the event that peace breaks down, war must therefore be “just” (bellum iustum). This explains the abundant coins minted during the Roman Empire on which Pax appeared on the reverse, with the emperor on the obverse. Although their wide circulation makes their monetary function clear, they also performed other functions, both political (e.g., strengthening the coiner's authority) and ideological. Thus we find Pax represented by a woman with various attributes- such as a spear, a caduceus (a rod of Mercury), a cist (a wooden box used in rituals)- standing over a sphere with a cornucopia (horn of plenty) or an olive branch, or identified with Justice. Other symbols include a temple and a handshake. The appearance on coins of expressions such a pax aeterna, pax et libertas, pax orbis terrarum and pax aeterna indicates the widespread ideological use of such coinages. International Relations Roman imperialism was based on the industry of war, which made possible conquests and the keeping of law and order, while at the same time allowing for the laborious process of negotiation an peace. War was the means for attaining wealth, slaves, land, and taxes in order for the Empire to operate successfully, and feverish diplomatic activity was undertaken to minimize problems and to foster contact and exchange. Army generals sought to achieve their war aims as expeditiously as possible, perhaps only to reach victory- Victoria was a form of negative pax because it guaranteed the end of war- attain glory, and be able to distribute the booty among their soldiers. With pax, soldiers were less likely to become victims of the struggle, and peasants (often forced into conscription, a form of involuntary servitude) were less likely to see their land ravished and impoverished, a situation that led to complete slavery form the debs contracted. It is clear what pax meant for the victorious elite, the emperors and the generals, who enjoyed the attainment of their aims (wealth, power), but for the vanquished and conquered communities, subjected to a foreign and violent power, pax was the means to an end: no more violence, or at least less violence, even though in the negotiation process their collective strengths and identity were at stake. That may be the reason for Seneca's assertion that, “To seek the return of peace is good for the victorious and necessary for the defeated …. Let a lasting peace grow among all peoples …. Let all iron be visible in the ploughshare and hidden in the swords”. For these reasons, the term pax resonates with its associations to other words with far-reaching temporal and spatial connotations: universa, longa, aeterna, diutura, perpetua, constans, semipterna, futura; pax thus became a guarantee for the living conditions of ensuing generations. These expressions broaden the scope of the term pax, its meaning taking on special senses when combined with nouns such as otium, tranquilitas, and concordia, all of which make up a lexical field encompassing a broad realm where pax is at work: personal, domestic, local, peninsular, provincial, and imperial. Bibliography: • MELKO, Matthew, and WEIGEL, Richard D. Peace in the Ancient World. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 1981. • MUÑOZ, Francisco A. and MOLINA RUEDA, Beatriz eds. “La Paz Romana”. In Cosmovisiones de paz en el Mediterráneo antiguo y medieval , pp. 191-228. Granada: Editorial Universidad de Granada, 1998. • SORDI, Marta. “Pax Romana”. In La Pace nel mondo antico, pp. 127-145. Milan: Vita e Pensiero, 1985. • WENGST, Klaus. Pax Romana and the Peace of Jesus Christ . Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1987. • ZAMPAGLIONE, Gerardo. The idea of Peace in antiquity. Translated by DUNN, Richard. Notre Dame, Ind.: University of Notre Dame Press, 1973. Si citas el texto, cita la fuente: MUÑOZ, Francisco A. “Pax Romana”. En: The Oxford International Encyclopedia of Peace. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press (USA), 2010. Pp. 350-352.