The Knight Saints. Keywords: Knight Saints, Military Saints, Warrior

Anuncio

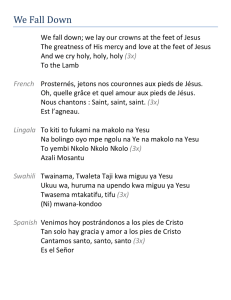

THE KNIGHT SAINTS Theme: The Knight Saints. Keywords: Knight Saints, Military Saints, Warrior Saints, Christian Saints, Miles Christi, Equites Christi, Bellator Domini. Summary: This theme comprises all the saints that, mounted on a horse, belong to a military order. They are usually represented vanquishing their enemy or fighting against the personification of evil or a monstrous creature. Generally, this iconography represents the eternal fight of good versus evil, where the knight expertly holding the reins of his horse symbolizes spiritual power, although in the case of Saint Martin of Tours it symbolizes charity since he is usually represented ripping his mantle in half to share it with a beggar. Attributes and types of representation: The knight saint appears in works of art dressed as a warrior or a soldier with his cloak waving in the air. He is usually armed with a spear that he uses to attack his enemy. Furthermore, he usually has a sword, a dagger and a shield. At the hooves of the horse, represented in a dynamic attitude either in a trot or in a curvet, the vanquished enemy is located in human, animal, or monstrous form. It is difficult to identify all the different knight saints since they have no other symbols that would make them identifiable. Primary sources: In the Old Testament there are many references to the horse, which has to be led to overcome evil, just like the knight saints do: • Deuteronomy 17:16: The king, moreover, must not acquire great numbers of horses for himself or make the people return to Egypt to get more of them, for the Lord has told you, “You are not to go back that way again.” • Proverbs 21: 31: The horse is made ready for the day of battle, but victory rests with the Lord. • Jeremiah 8: 6: I have listened attentively, but they do not say what is right. No one repents of his wickedness, saying, “What have I done?” Each pursues his own course like a horse charging into battle. • Psalms 32: 9: Do not be like the horse or the mule, which have no understanding but must be controlled by bit and bridle or they will not come to you. • Psalms 33: 17: A horse is a vain hope for deliverance; despite all its great strength it cannot save. Even though there are very few iconographical variants between the knight saints, each one of them has its own legend that gives meaning to his representation1. The ideal knight saint is assimilated into the medieval knight. In the Pontifical of Guillaume Durand, from the second half of the 13th century one can read: “Señor muy santo, Padre todopoderoso… Tú que has permitido sobre la tierra el empleo de la espada para reprimir la malicia de los malos y defender la justicia; que, para la protección del pueblo, has querido instituir la orden de la caballería… haz, disponiendo su corazón hacia el bien, que este servidor tuyo no use nunca este acero ni otro alguno 1 See for each case Reau (1997), part 2, vols. 3-5, Vorágine (1982), 2 vols., Revilla (1990), Roig (1991), Tradigo (2004), Carmona Muela (2003), Duchet-Suchaux, G. y Pastoureau, M. (1996). para perjudicar injustamente a nadie; sino que se sirva de él para siempre con objeto de defender la Justicia y el Derecho”2. Other sources, non-written sources: The knight as vanquisher of evil is present in many legends from Antiquity where it is usually related to scenes of war and the hunt. In Western Europe, the horse, also connected with impetuous strength, was soon associated with members of higher social status as the symbol of power. In addition, the capacity of the nobleman to overpower his enemies while on horseback conferred him a high degree of moral superiority. That is why the stories of heroes are always connected with knights that mounted on a horse have more possibilities of achieving heroic deeds. Furthermore, when evil is represented, it is usually in the form of a dragon since it is the symbol of the dark powers and the obstacle that needs to be overcome. Geographical and chronological framework: The presence of knight saints can be confirmed from an early date in Christian art. In ivory, textiles and other sumptuary arts, equestrian figures were represented. At first they made reference to heroes from Antiquity like Alexander the Great, but later on they adopted a Christian symbolism making the knight saint that conquers evil the allegory of the victory of Christianity over Paganism. In the Eastern Church, many saints were represented with military insignias since many of them were supposed to have been members of the military such as Saint Acacius, Saint Adrian, Saint George, Saint Menas, Saint Mercury, Saint Sisinius, Saint Theodore, Saint Theophulius, Saint Victor, and Saint Zenon. Some of these Eastern saints were also venerated in the West, like Saint George, but others came directly from Western Europe, such as Saint Martin of Tours (although he presents an iconographical variant when he shares his cloak with a beggar, an act that symbolizes charity, rather than fighting evil). Another Western saint is Saint James, more commonly found in medieval Spain. These military saints were especially venerated in Byzantium, where their iconography was set. Some of the most important saints were Saint Theodore and Saint Demetrius from Thessalonica, who usually are represented killing a pagan king with a spear. Saint Demetrius became the patron saint of the Crusaders and as such his cult spread very rapidly. Within the Byzantine sphere of influence, the Copts in Egypt were very devoted to these military saints whose iconography was already firmly established in the 6th and 7th centuries, an iconography that was based on the image of Roman emperors. This iconography could be found in mural paintings, in stone stelae, metalwork, woodwork, ivory, textiles or manuscript illumination.3 For the Coptic community the horse was a symbol of good and owning a horse was a good premonition, an almost impossible deed since the Muslims prohibited the Copts the ownership of horses4. The military saints of the Eastern Church were characterized by their iconographical similarities, something that hinders the individual identification of the saints. For example, the Russian saints Boris and Gleb are represented like Saints Demetrius and George. 2 3 4 Revilla (1990), p. 71. The mural painting of the monastery of Bawit is very important in this respect since it shows the spiritual combat between Saint Sinisius killing the half naked female devil Alabasdria with a spear, while the background is full of animals and hybrids that symbolized the temptations that the saint had to overcome: Zibawi (2003), p. 78. In many textiles from the Valley of the Nile there are many horseback riders that in some cases appear in hunting scenes, in other cases they appear fighting Persian warriors, and in other cases a hero from Antiquity would appear like Alexander the Great, and yet in other cases haloed saints appear vanquishing evil and end up crowned after they defeat it in their spiritual fight: Rutchowscaya (1990), p. 142-143, L’Art copte en Egypte (2000), p. 172. Cannuyer (2000), p. 66. The most popular knight saint in the Western church was Saint George whose cult spread all over Europe as a consequence of the Crusades. Saint George became the patron of the Christian knights and soldiers since he represented the best example of milites Christi. Among the apocryphal stories of this saint, the most famous one was his battle against a dragon to save a princess. This story became the basis for the most widespread iconography of the saint, where he appears on a horse fighting the dragon and the princess watches on the side the confrontation. He was named patron of the Kingdom of Aragon, where he was widely represented in the Catalan - Aragonese art of the Late Middle Ages. Nevertheless, examples of this iconography can be found all over Europe in different media and techniques that show the diffusion of his cult. Saint James the Moor-Slayer appears for the first time as the conqueror of the infidel in the battle of Clavijo in the tympanum of the south transept of the Cathedral of Saint James in Compostela (first third of the 13th century) and it was not until 1326 that he would be represented with the same iconography in the B Tomb of the above mentioned cathedral. From this moment on, this iconography became one of the most common typologies for Saint James in Spain and Latin America. The images of the knight saints have been represented throughout all the artistic periods up until today with very peculiar examples but with very few iconographical changes. Artistic media and techniques: The different knight saints can be found in all the different artistic media and techniques related not only to the sumptuary arts, such as ivory, metalwork, stained-glass, ceramics, textiles, manuscript illumination, but also in sculpture, woodwork, mural painting and oil painting. In Byzantium, in addition to the sumptuary arts, the many icons that have survived allow us to study the development of this iconography. Precedents, transformations, and projection: The artistic representation of the knight was born in the East, where already in the 7th century B.C. horse riders armed with bows or spears appeared in war and hunting scenes5 following the Zoroastrian principles of the battle between good and evil. This imagery was later extended during the reign of Alexander the Great to Hellenistic Greece,6 where the diffusion of the equestrian figure of Alexander the Great became the standard imperial iconography of the triumphant emperor -adventus-.7 This iconography became the model of the knight-saints especially in Byzantium and in Coptic Egypt, a model that later on would be expanded to Western Christianity. In Egypt, due to Sassanian and Byzantine influences, the equestrian military saints were highly venerated8; nevertheless, it would be important to point out that there is an autochthonous antecedent in Egyptian mythology in the figure of Horus defeating Seth, his envious uncle with whom he fights to avenge the death of his father Osiris. The typical image to represent this scene can be seen in a sculpture from the Louvre Museum, dated to the mid-4th century, where the god with the body of a human and the head of a falcon, dressed as a 5 6 7 8 The “Assyrian Calvary” from the palace of Assurbanipal in Niniveh (Louvre Museum), or the frieze of the “lion hunt” from the same place (British Museum, London). Many funerary votive sculptures of Thracian origin have been preserved from the 2nd century B.C. with horseback riders hunting: Bianchi Bandinelli (1970), figs. 286-290. Besides the imperial monumental equestrian sculptures, it is important to emphasize the diffusion of this iconographical model through sumptuary objects such as the “Kertch plate”, made in Constantinople and dated to the 4th century A.C. (Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg) or the “Barberini ivory” from the mid-6th century (Louvre Museum). See the examples of equestrian saints in Zibawi (2003), pp. 78, 183, 184, 216. Fore more details about the origin of this topic in Egypt, see: Rutschowscaya (1990), pp. 140-141. Roman soldier and mounted on a horse with a spear, faces the chthonic god of brute force and the uncontrollable personified in the form of a crocodile, a figure who in the afterlife was in charge of tearing the souls that did not pass the judgment of Osiris9. Following the equestrian figures of Iranian art, this motif obtained a different meaning since it signified the symbolic image of glory characterizing the knight saint as an ancient triumphant hero. Typology and related themes: The knight saints symbolize the spirit that dominates over matter and they evoke the triumph of a militant Christianity, where the signs of violence are mitigated by the altruistic aim of their actions. In this respect, the same symbolism can be attached to the Christian knights than to the ones in Iranian art, the Greek heroes such as Alexander the Great or the triumphant entrance of the emperors. The parade of the blessed knight saints that move towards the divinity is a re-enactment of real active knights. The knight saints are also represented on foot, armed and with military costumes in Eastern art -the Harbaville Tryptich (Louvre Museum)- and in Western art -Saint George and the princess in Jaume Huguet's painting (Museo Nacional de Arte de Cataluña). Images: - Saint Sisinio kills the she-devil Albasdria, 6th and 7th centuries, Coptic art, drawing made by J. Clédart following a mural painting, Bawit Monastery (Egypt). - Knight Saint, 9th-10th century, textile from the Valley of the Nile, linen and wool, 33x34 cm., number inv, 2481A.2 (D),140 (coll. tissus coptes), 8 (number Cat. Cent chefs-d'oeuvre), Museo Departamental de Antigüedades de Seine-Maritime, Rouen (France). - Saint Theodore the Anatolian, 10th century, Coptic art, manuscript illumination, 33,4x26 cm., M. 613, Pierpont Morgan Library, New York (USA). - Saint Theodore the Anatolian, 11th century, Coptic art, fresco, Convent of Saint Anthony (Egypt). - Saint George, 14th century, Novgorod workshop, panel painting, Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg (Russia). - Saint Boris and Gleb, 1st half 14th century, panel painting, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow (Russia). - Pere Joan, Saint George, ca. 1420, stone, Palacio de la Generalitat, Barcelona (Spain). - Bernat Martorell, Saint George and the dragon, ca. 1430, panel painting, Art Institute, Chicago (USA). - Paolo Uccello, Saint George and the dragon, 1460, panel painting, National Gallery, London (United Kingdom). - Saint James the Moorslayer at the battle of Clavijo, 1st third of the 13th century, stone, tympanum at 9 Bourguet (1967), p. 78 y pp. 95-96. This image has been related to that of the triumphant emperors. It is important to take into consideration the artistic representations of the pharaohs on horseback cannot be found until the Ptolemaic period, because in Egypt horses were reserved for soldiers while the pharaohs and other dignitaries used the chariot. the south transept, Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela (Spain). - Saint James the Moorslayer, 1326, manuscript illumination, Tumbo B, cathedral of Santiago de Compostela (Spain). - Saint James the Morrslayer, ca. 1515, wood, Saint Martin altarpece, Church of James Apostle, Medina del Campo, Valladolid (Spain). - Simone Martini, Saint Martin sharing his cape with a beggar, 1317-1319, fresco, Chapel of Saint Martin, Lower Church of Saint Francis, Asisi (Italy). - Gonçal Peris, Saint Martin of Torres Altarpiece, 314x260 cm. Panel painting, Museo de Bellas Artes, Valencia (Spain) Bibliography: L’art copte en Égypte, 2000 ans de christianisme (2000): Institut du Monde Arabe, Paris BIANCHI BANDINELLI, R. (1970): Roma. Fin del Arte Antiguo, El Universo de las Formas, Aguilar, Madrid BOURGUET, P. (1967): l’Art Copte. L’Art Dans le Monde, Albin Michel, Paris CANNUYER, C. (2000): L’Égypte copte. Les chrétiens du Nil. Institut du Monde Arabe, Gallimard, Paris CARMONA MUELA, J. (2003): Iconografía de los santos, Istmo, Madrid CORTÉS ARRESE, M.A. (1993): “La imagen de San Jorge en el arte bizantino” en Oriente y Occidente en la Edad Media. Influjos bizantinos en la cultura occidental, Actas de las VIII Jornadas sobre Bizancio, Instituto de Ciencias de la Antigüedad, Vitoria, pp. 247-260 DELEHAYE, H. (1909): Les légendes grecques des Saintes militaires, Paris DUCHET-SUCHAUX, G. y PASTOUREAU, M. (1996): Guía iconográfica de la Biblia y los santos, Alianza, Madrid RÉAU, L. (1997): Iconografía del Arte Cristiano. Iconografía de los santos. Part II, Vols. 2, 4, 5, El Serbal, Barcelona REVILLA, F. (1990): Diccionario de iconografía, Cátedra, Madrid RUTSCHOWSCAYA, M.H. (1990): Tissus coptes, Adam Biro, Paris RODRÍGUEZ PEINADO, L. (1993): “Las representaciones ecuestres de los tejidos coptos. Evolución de un tema iconográfico a propósito de dos tejidos del Museo Nacional de Artes Decorativas”, Cuadernos de Arte e Iconografía, pp. 225-230, Madrid ROIG, J.F. (1991): Iconografía de los santos, Omega, Barcelona TRADIGO, A. (2004): Iconos y santos de Oriente, Electa, Barcelona VORÁGINE, S. de la (1982): La leyenda dorada, 2 vols., Alianza, Madrid WITTKOWER, R. (2006): La alegoría y la migración de los símbolos, Siruela, Madrid ZIBAWI, M. (2003): Images de l’Égypte chrétienne. Iconologie copte. Picard, Paris Author and e-mail address: Laura Rodríguez Peinado, lrpeinado@ghis.ucm.es