Literatura inglesa V: Study guide

Anuncio

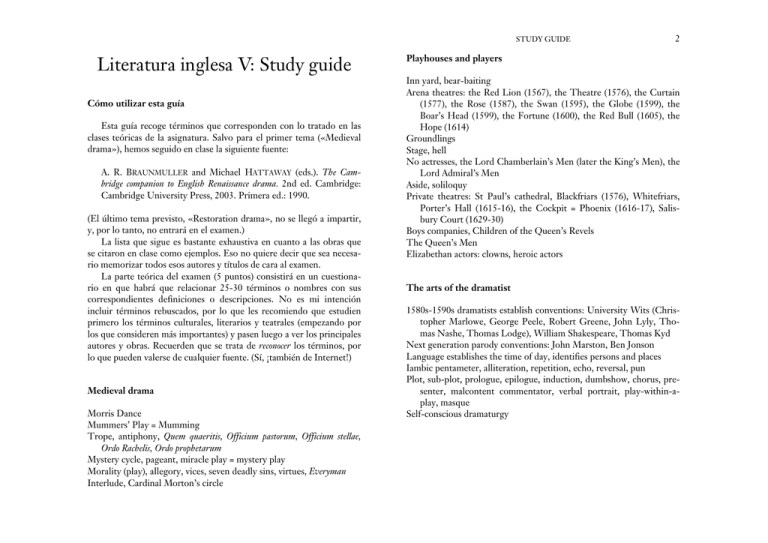

STUDY GUIDE Literatura inglesa V: Study guide Cómo utilizar esta guía Esta guía recoge términos que corresponden con lo tratado en las clases teóricas de la asignatura. Salvo para el primer tema («Medieval drama»), hemos seguido en clase la siguiente fuente: A. R. BRAUNMULLER and Michael HATTAWAY (eds.). The Cambridge companion to English Renaissance drama. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. Primera ed.: 1990. (El último tema previsto, «Restoration drama», no se llegó a impartir, y, por lo tanto, no entrará en el examen.) La lista que sigue es bastante exhaustiva en cuanto a las obras que se citaron en clase como ejemplos. Eso no quiere decir que sea necesario memorizar todos esos autores y títulos de cara al examen. La parte teórica del examen (5 puntos) consistirá en un cuestionario en que habrá que relacionar 25-30 términos o nombres con sus correspondientes definiciones o descripciones. No es mi intención incluir términos rebuscados, por lo que les recomiendo que estudien primero los términos culturales, literarios y teatrales (empezando por los que consideren más importantes) y pasen luego a ver los principales autores y obras. Recuerden que se trata de reconocer los términos, por lo que pueden valerse de cualquier fuente. (Sí, ¡también de Internet!) Medieval drama Morris Dance Mummers’ Play = Mumming Trope, antiphony, Quem quaeritis, Officium pastorum, Officium stellae, Ordo Rachelis, Ordo prophetarum Mystery cycle, pageant, miracle play = mystery play Morality (play), allegory, vices, seven deadly sins, virtues, Everyman Interlude, Cardinal Morton’s circle 2 Playhouses and players Inn yard, bear-baiting Arena theatres: the Red Lion (1567), the Theatre (1576), the Curtain (1577), the Rose (1587), the Swan (1595), the Globe (1599), the Boar’s Head (1599), the Fortune (1600), the Red Bull (1605), the Hope (1614) Groundlings Stage, hell No actresses, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men (later the King’s Men), the Lord Admiral’s Men Aside, soliloquy Private theatres: St Paul’s cathedral, Blackfriars (1576), Whitefriars, Porter’s Hall (1615-16), the Cockpit = Phoenix (1616-17), Salisbury Court (1629-30) Boys companies, Children of the Queen’s Revels The Queen’s Men Elizabethan actors: clowns, heroic actors The arts of the dramatist 1580s-1590s dramatists establish conventions: University Wits (Christopher Marlowe, George Peele, Robert Greene, John Lyly, Thomas Nashe, Thomas Lodge), William Shakespeare, Thomas Kyd Next generation parody conventions: John Marston, Ben Jonson Language establishes the time of day, identifies persons and places Iambic pentameter, alliteration, repetition, echo, reversal, pun Plot, sub-plot, prologue, epilogue, induction, dumbshow, chorus, presenter, malcontent commentator, verbal portrait, play-within-aplay, masque Self-conscious dramaturgy 3 LITERATURA INGLESA V STUDY GUIDE 4 Drama and society Romance and the heroic play Social mobility, sumptuary laws, educational revolution (more university-educated males without access to honour or office), geographical mobility, economic individualism The court, centre of patronage (reward) and court of law (punishment), corruption, revenge tragedy The city, knaves and fools Woman, domestic drama, shrew, witch, whore Romance, heroic play Sir Clyomon and Sir Clamydes (1570) Early-Elizabethan dramatic romance retains medieval conventions: characters directly announce their identity to the audience, motives are openly asserted, expository speeches are delivered, the audience is frankly acknowledged Idealized aristocratic life, vagueness (adequate at court) evades censorship Popular romance (remote heroes), court romance (oblique application to real persons of the time) Marlowe’s Tamburlaine (1587), blank verse Plays about popular heroes: George in Greene’s George a Greene the Pinner of Wakefield (1590), Talbot and Joan of Arc in Shakespeare’s Henry VI, part I, and Jack Cade in part II Plays with London as subject: Thomas Dekker’s The Shoemaker’s Holiday (1599) Burlesque: Thomas Heywood’s The Four Prentices of London (1594), Francis Beaumont’s The Knight of the Burning Pestle (1608) Private and occasional drama Private drama differs from public drama: no willing suspension of disbelief, no real dialogue between characters (they address the chief spectator), and no clear division between ‘spectator’ and ‘participant’ (masquers take dancing partners out of the audience) Court, ‘offering to the prince’ genre, George Peele’s The Arraignment of Paris (1581-84), royal progress, masque, Ben Jonson, Inigo Jones, masque and antimasque Inns of court, universities, Christmas princes, royal visits, ‘saltings’ (parodies of academic disputations) Aristocratic houses Political drama Historical play = political play Censorship, Master of the Revels Patronage Chronicle play: nationalism, warlike monarchism, anticlericalism, fear of Catholic invasion and plotting Dramatized reigns of kings who got deposed: Marlowe’s Edward II, the anonymous Woodstock, Shakespeare’s Richard II After Essex rebellion (1601), no more celebratory national history; no longer battles, but dissolute courts Revenge tragedy = tragedy of blood ‘Elect Nation’ plays, Puritans, John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs Pastiche, burlesque, tragicomedy Pastiche, John Marston’s Antonio and Mellida, Antonio’s Revenge (15991600) Burlesque, Francis Beaumont’s The Knight of the Burning Pestle (1608) Tragicomedy, Giambattista Guarini, satire Marston’s The Malcontent Beaumont and Fletcher’s Philaster (1609), A King and No King (1611) Shakespeare’s Cymbeline Webster’s The Devil’s Law Case Middleton and Rowley’s A Fair Quarrel 5 LITERATURA INGLESA V Comedy Shakespearean comedy = romantic comedy, Jonsonian comedy = satiric comedy, farce, romance Three phases: exposition and beginning of the action, complication of incidents, anastrophe or resolution Interlude, Heywood’s The Four P.P. Academic comedy: Plautus and Terence, Gammer Gurton’s Needle, Nicholas Udall’s Ralph Roister Doister Eclectic comedy: John Lyly’s Endymion (1587-88), George Chapman’s Gentleman Usher (1606), John Fletcher’s The Wild Goose Chase (1621), Rule a Wife and Have a Wife (1624) Comedies that adopt plots from Plautus and Terence but heighten romance and satire: Shakespeare’s Comedy of Errors (1590-93), George Chapman’s All Fools (1599-1601) Nocturnal comedy: Henry Porter’s Two Angry Women of Abington (1598), the anonymous Merry Devil of Edmonton (1600-1604) Citizen comedy = Jacobean city comedy (“critical and satiric design, urban settings, exclusion of material appropriate to romance, fairytale, sentimental legend or patriotic chronicle”), Ben Jonson’s Everyman in his Humour (1601), The Alchemist (1610), The Staple of News (1626), John Marston’s The Dutch Courtesan (1603-1605), Thomas Middleton’s A Chaste Maid in Cheapside (1613), Philip Massinger’s The City Madam (1632) Shakespeare’s seventeenth-century comedies introduce uncertainty (comedy, an inadequate representation of human experience): Troilus and Cressida, All’s Well That Ends Well, Measure for Measure Tragedy Aristotle: “tragedies must represent a complete, serious, and important action that rouses and then purges (by catharsis) fear and pity in the spectators, with a central character who moves from happiness to misery through some frailty or error (hamartia)” STUDY GUIDE 6 Nietzsche: tragedy is the battle “between Apollo (the god of civilization, rationality, daylight) and Dionysius (the god of frenzy, passion, midnight)” Hegel: in tragedy “a heroic individual becomes trapped between the conflicting demands of two godheads, between two sets of values that are each imperative and mutually exclusive” De casibus tragedy = fall of princes tragedy Domestic tragedy The revenger, the malcontent, the Machiavel (cf. Machiavelli’s The Prince) Revenge tragedy, Seneca, closet drama, Thomas Kyd’s Spanish Tragedy (1582-92), Shakespeare’s Hamlet (1601), Cyril Tourneur’s (?) The Revenger’s Tragedy (1607) Theodicy (“the inquiry into the nature of evil and the means by which it enters Creation”), Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus, blank verse, Shakespeare’s Othello (1603-1604), John Webster’s The Duchess of Malfi (1612-13) Caroline drama Cavalier drama Marriage and woman’s place, the responsibilities of class, James Shirley’s Hyde Park (1632), Philip Massinger’s The Picture (1629) Tragedies: Shirley’s The Traitor (1631), John Ford’s ’Tis Pity She’s a Whore (1633) Theatre discusses its own function: Massinger’s The Roman Actor (1626), Ford’s The Lover’s Melancholy (1628), Richard Brome’s The Antipodes (1640) City comedy (Jonson was influential but his own Caroline plays were unpopular): Shackerley Marmion’s Holland’s Leaguer (1631), Brome’s The Weeding of Covent Garden (1632), William Davenant’s The Wits (1634), Jonson’s The New Inn (1629) Neoplatonism, Thomas Killigrew’s The Parson’s Wedding (1637)