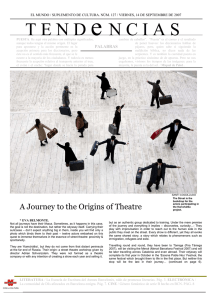

Meiji Gakuin University Tokyo March 2016 ‘Revisiting Greek Tragedy on the Modern Stage The Example of Tadashi Suzuki’ *** Good evening, everyone. It is a pleasure and an honor to speak here, at Meiji Gakuin University, today. Before I start, I would like to express my warmest thanks to Professor Nakajima and to Professor Daido; Very special thanks to the Ambassador of Greece in Japan, Mr. Loukas Karatsolis and all the Embassy staff for making this lecture possible. My gratitude extends to the Japan Foundation for granting me the unique opportunity to spend some time on site to research contemporary Japanese theatre. Last but not least, thank you each and everyone of you for sparing the time to listen to some of my thoughts on ancient Greek tragedy and its reception internationally. *** So I am going to start my lecture by stating what is perhaps obvious to most: that in the ever-revised crisis of civilization, it is becoming imperative to regain our autonomy of feeling. I believe that contact with the ultimate archetypes of the human condition, embedded in the ancient Greek plays, can safeguard such autonomy. Nietzsche had long ago claimed that without myth every culture forfeits its healthy, creative natural power: ‘only a horizon encompassed by myths locks an entire movement of culture into a unity’ (Nietzsche 1999: 23). Fundamental and primordial, old myths occasion a cataclysmic cancellation of most dividing lines and lend themselves to guilt-free ownership. Particularly with respect to tragedy, the classical works’ relevance in our ferociously mediatized times keeps resurfacing whenever a 1 new production comes to contemporize what is fundamentally timeless. Internationally, avant-garde directors’ innovative versions for the most part serve to perpetuate the ancient plays’ established value. Not only do they guarantee their longevity; they provide a continuous –if posthumous—acknowledgment of merit and relevance. On their part, classical works have repeatedly astonished us with their resilience, bouncing back each time, after a ‘ferocious’ directorial ‘attack’ has been launched. Ιndeed, through such readings, as Linda Hutcheon argues, ‘stories do get retold in different ways in new material and cultural environments; like genes, they adapt to those new environments by virtue of mutation—in their “offspring” or their adaptations. And the fittest do more than survive; they flourish’ (2006: 32). Erika Fischer-Lichte has drawn attention to the distance of the ancient texts, which any staging should bring to the light and insists that revivals are actually unable to access the past because [it] is ‘lost and gone forever. What remains are only fragments – play texts torn out of their original contexts – which cannot convey their original meaning’ (2005: 234). One of the purposes of staging the Greek texts is to remind ourselves of this distance, find ways of coping with it individually and insert fragments of these texts into the context of our contemporary reflections, life and culture. Evidently, directors need to search for ways to expose the remoteness of the classical work and celebrate the formal gap that separates us from the time of its birth. In this way, they can startle us with new insights, as a rule uncomfortably placed between the past of the work’s conception and the present of its reception. Seen in this light, the term ‘requotation,’ employed by the acclaimed Japanese director Tadashi Suzuki, to suggest that the original story has been “rearranged and transformed” (Neely 1987: 515), would perhaps be an apt alternative to adaptation, engaging, as it does, both past and present. 2 Why exactly do we ‘latch on to a theatrical world of dystopia which relentlessly confronts us with the spilling of kindred blood and the breaking of just about any taboo imaginable within the human realm?’ (Revermann 2008: 104). As a genre, ancient Greek tragedy is simultaneously foreign and familiar, featuring an enticing complementarily that is rare. In point of fact, Greek tragedy’s humanistic perspective provides an intellectual sort of homecoming. One might argue that the key to the viewing of Aeschylus’, Sophocles’ and Euripides’ plays as a cultural bridge lies in the understanding, acceptance, and use of a contradiction: tragedy is both a cultural product and a universal property. In a global community, it soothes our anguish of unrootedness. By turning politics and religion into dramatic conflict, it forces us to consider our own position in society and also come to terms with our mortality. While the ubiquity of hyphenated forms threatens to undermine or displace emphasis on story and intelligible linguistic codification, the Greek plays and the myths they encompass can function as anchors of identity—encapsulating ‘underlying, inarticulate assumptions about the world and human existence’ (Baeten 1996: 25). For the most part, in the analysis of tragedy, the literary author’s assumed intentions will remain uncharted. While the dramatic canon grants us the comfort of re-understanding fundamentals and reconsidering absolutes from afar–thus sparing ourselves the pain that ensues from instant identification with violent or atrocious emotions—the practice of adaptation seems to legitimize directorial choices that would remain mostly unacceptable in mainstream theatre. No longer will directors treat Greek tragedy’s linguistic, structural and contextual limitations as a sacrosanct given; on the contrary, most will tamper with the form with a desire for appropriation, which in itself betrays a sense of entitlement over tradition and the interpretation 3 thereof.1 As Umberto Eco had suggested, since the past cannot be destroyed, because ‘its destruction leads to silence,’ it must be revisited: ‘but with irony, not innocently’ (Eco 1984: 67). Still, many radical productions of Greek tragedy have consistently manifested an ambivalent attitude towards the classics, their means of reframing the source (original) text resounding a broader disquiet regarding the treatment of the ‘great narratives.’ Their wavering shelters some of the insecurities that Roland Barthes had been suggesting in his 1979 discussion of Greek drama: [W]e never manage to free ourselves from a dilemma: are the Greek plays to be performed as of their own time or as of ours? Should we reconstruct or transpose? Emphasize resemblances or differences? (Barthes 1979: 59) A classic, tells us Italo Calvino, is a work which persists as background noise, even when a present that is totally incompatible with it holds sway (Calvino (1985) 2000: 8). No less firmly, George Steiner attributes the classic’s integral authority to the quality that allows it to ‘absorb without loss of identity the millennial incursions upon it, the accretions to it, of commentary, of translations, of enacted variations’ (Steiner 1984: 296-7). Simply retelling the story that Euripides or Sophocles have already given us, with no consideration of the factors that can still render it relevant today is no longer a viable artistic endeavour; every time such ‘ghost productions’ open, the vital text falls into deep slumber and eventually dies, having aged inexorably in the first few minutes. Much of modern theatre’s inability to arouse any genuine reactions in today’s disillusioned audiences could be partly attributed to the fallacy of recreating–or slavishly aping–the imagined conditions of an era no longer 1 See more of this in Sidiropoulou 2014 and 2015 4 applicable or interesting to us. What French semiologist Patrice Pavis terms ‘archaeological reconstruction’ has long ceased to be the ‘representational ideal of a classical work’ (2013: 207), since it ignores the unique circumstances of the audience at the point of reception and thus results in an echo–rather than a distillation–of the original story. In fact, as Fischer-Lichte argues, ‘whatever we think we know about the past is a kind of reinvention-a construction, a fantasy’ (Fischer-Lichte in Hall, Macintosh and Wrigley 2004: 352). Essentially, the strains that corrode revisionist stagings have a lot to do with critics’ and spectators’ opposing sets of expectations of fidelity: on the one hand, a faithfulness to the original work, a conservative attitude, and on the other, a furtive, unacknowledged desire to be surprised by the product. Fully aware of this paradox, directors like Suzuki–whose eclectic style is a ritualistic, almost religious reflection of a world that has been torn to pieces and put back together in new forms— turn to tragedy not as ‘simply a thing of the past, an archaeological relic [but as something] totally projected into the future,’ [something] ‘inevitable’ (Castelluci in Laera 2013: 185). Suzuki’s revisionist interpretations of Greek tragedy ever since the 1970s have carried within them the paradox of a conflicting desire/ to remember and to change, to revive and to bury. Ιn his own words: ‘I don’t do a reading of the script. The best action is to create a whirlpool of new material creation out of the old’ (qtd in Carruthers and Takahashi 2004: 152-153). Suzuki’s art testifies to the conviction that this “rootedness” of Greek drama, combined with its “otherness”, has turned it into an ideal shortcut, a liberating format which helps the artist, and the political activist, to circumvent, legitimately and with playful ease, centuries of cultural baggage’ (Revermann 2008: 108). In this sense, ‘the mythical, dysfunctional, conflicted world’ of the Greeks has established itself as one of the ‘most important cultural and 5 aesthetic prisms through which the real, dysfunctional, conflicted world of the late twentieth- and early twenty-first centuries has refracted its own image’ (Hall in Hall, Macintosh and Wrigley 2004: 2). *** All over the world, in the work of avant-garde artists involved in staging tragedy (Katie Mitchell, Ivo van Hove, Romeo Castelluci, Frank Castorf, Jan Fabre and Τheodoros Terzopoulos, among many others), the dialogue between the original text and its re-writing has kept alive the fascinating battle for authorship and parenthood of the adaptation. At the heart of the process of revision, recontextualizing an established myth by means of ‘proximation’ (Sanders 2006: 21) is a mechanism of bringing home to the audience its essential yet uncompromisingly remote elements. In the Greek plays, such is, for example, the presence of a Chorus and of the Olympian gods. Using strong metaphors and timely cultural reference, directors rethink fundamental archaic notions such as hubris, nemesis, suffering and catharsis. Being the ‘closest “other” there can possibly be’ (Revermann 2008: 110), placed as it is in a kind of ‘public domain,’ Greek tragedy has become an ideal place for Tadashi Suzuki, based in Toga, Japan, to vent off his social, political and ideological discontent. His stage metaphors imaginatively substitute for tragedy’s elements of alterity, while the synthetic ambiguity of his mise-en-scène accommodates both the distance and the timelessness of the ancient text, avoiding the dangers that belie such conjunction. For the Japanese director, staging tragedy’s constitutional ‘strangeness’ in the end also means returning to his own tradition’s performance forms, such as Noh, Kabuki and Bunraku, in order to confront elements as alienating as the tragic Chorus, the heightened language, the stylized movement 6 and the use of masks. This dialogue between different methods and traditions is also present in another celebrated Japanese artist, Yukio Ninagawa, whose 1978 Medea was done in the Kabuki tradition, with an all-male cast. Such revisiting suggests a desire to ‘recapture the energy of the primitive theatre’ (McDonald 1992: 29). Suzuki’s stage versions of Euripides are set in thoroughly changed environments, always of noted cultural significance, yet also of an archetypical nature, and are replete with emotional resonance. In the acclaimed production of Trojan Women (1974), the action takes place in a cemetery, among the ruins of a warwrecked city. Wishing to put forth to his audience a deathly milieu recalling the Hiroshima atrocity, Suzuki opts for perhaps the most symbolic of all sites. Fundamentally, reinterpreting Greek tragedy for him comes from the need to ‘exorcise the emotional wounds of his childhood’, but is also an attempt to process the social and political transformations of Japanese history, traditions and identity (Allain 2002: 20). Suzuki’s work, however, has always managed to transcend national barriers, providing powerful humanistic commentaries. Trojan Women —an expressionistic, almost ‘plotless treatise against the horrors of war, where narrative tension is replaced by emotional anxiety’ (Allain 2002: 153)— reverberates with imagery from the holocaust: an old woman survivor, assumed to have lost husband and children in the war, roams the destroyed city, carrying a sack which contains several household objects mixing the old and the modern (characteristically, a teapot, an empty can, ‘Priam’s shoe’). The function of a bag containing the last cherished possessions that a war victim can hold to, feels particularly poignant, and its use on stage gradually transforms into a resonant, emotionally charged metaphor for family and home. As Carruthers relates, Suzuki’s motifs have sources in his memories as a child growing up during the war, attuned to the ‘shriek of the bombs, their sizzling 7 missiles in the harbor’ (Carruthers 2004: 153). More than anything, he remembers the women trying to protect their children. In a most visceral scene, Andromache’s son, Astyanax, portrayed on stage as a ‘white muslin doll with long arms’ is metaphorically slain by the soldiers, ‘its arm cut off, and hurled at the grandmother for burial’ (McDonald 1992: 37). Thus, in more than one way, Greek drama has become a significant site for working out these antinomies of nostalgia for a past, which is unrecoverable (Hardwick in Martindale and Thomas 2006: 211). Through the specific depiction of Japan and its post-war identity crisis, Suzuki ‘symbolized the general, without making it banal’ (Allain 2002: 154). As the director intimates: I do not think any other work has so successfully expressed one aspect of universal man. Nor is this just because war itself remains a present reality for us. The fundamental drama of our time is anxiety in the face of impending disaster. (Qtd in Allain 2002:154) Years later, in 1995, using another striking metaphor, Suzuki situates his version of Euripides’ Electra, Electra, Waiting for Orestes in a psychiatric clinic; one is instantly struck with the bizarre appearance of five wheel-chaired men in shorts–the Chorus–who circle the stage, moaning and howling, virtually justifying the director’s conviction that ‘all the world’s is a hospital, and all men and women merely inmates.’ The metaphor of a wheelchair reveals not ‘a physical dependency on something outside of ourselves, but rather a psychological dependency that occurs within ourselves’, in the director’s own words (qtd in Cooper 2012). Specifically for the production at the Delphi Stadium in Greece, Suzuki used zebra-crossing walkways that intersected ‘at the navel of the world’. These suggested both a modern traffic intersection and an abode of the dead, for the black and white strips of cloth he used were Japanese funeral awnings. Such flexible playing spaces, allowed architectural 8 structures and set designs to frame and accentuate actor rhythms and proxemics (Carruthers in Mitter and Shevtsova 2005: 168), besides bearing symbolic resonances of universal plight. For Suzuki, tragedy’s expansive inner space houses the perennial extremities of the human condition and addresses current disquiet. For one thing, his subtle treatment of politics finds in tragedy fertile ground on which to grow. His first version of the Bacchae (1978) was set up as a metatheatrical gest of revenge, which had the inmates of a prison reenact Euripides’ play/ and impersonate the oppressed Bacchantes, who come in direct confrontation with the state ruler Pentheus. Ιronically, however, the performance ends in the way in which it began, with King Pentheus returning on stage in an allegorical resurrection of the oppressor’s power; a visual statement echoing Suzuki’s profound disillusionment and pragmatic awareness. In his own words, ‘a nightmarish vision but a brutal fact repeated ever since the beginning of political history –a moment of festive liberation cruelly crushed down by the despot’ (qtd in McDonald 1992: 61). By virtue of its play-within-a-play frame, the production clearly makes a shocking use of the Chorus idea. Indeed, as an ‘uninvited guest’ (Laera 2013: 132), the Chorus has often stretched the limits of directorial interpretation to phenomenal extremes. Sometimes, as is the case with Suzuki’s production, its central position serves to highlight a more political and socially driven perspective. Challenging the authority of the Greek plays, a revamped Chorus carries the tension of a ‘body’ that is simultaneously foreign (an archaic convention) and public (representing the humanistic and democratic ideals of community). In daring to put out in the open the big, unresolved issues that continue to trouble people and societies, Suzuki finds in the Greeks a forum for easing or settling mental and psychological unrest and simultaneously ‘mourns and celebrates’ Japan’s 9 loss of innocence (McDonald 1992: 39). A cultural mélange and a bringing together of different temporalities is a recurrent motif: contemporary popular songs interrupt the past, mass culture intruding into the rituals of the ancient world. Intense preoccupation with the effects of consumerism also allows him to intersperse his performances with several popular art tokens, such as the cylindrical red-and-white Marlboro ashcans in his Bacchae. Such patterns of defamiliarization force us to look beyond the expected for a meaningful connection between text and sub-text. In the second treatment of the Bacchae (first performed in Milwaukee, US, in 1981), the dialogue between Japanese and American actors strikes a fundamentally ‘strange’ chord, while in Clytemnestra (1983), based on the tragedies that relate to myth of the House of Atreus, the actor performing Orestes is the sole Western figure on stage. The action takes place in Orestes’ mind; after the son murders the mother, she comes back as a Ghost who kills him while he is committing incest with his sister, Electra. In this performance, which essentially deals with family conflict and the battle of sexes, the eclectic costuming heightens the clash between tradition and modernity: the play opens with the trial scene from Eumenides, in which Apollo and Athena–both performed by male actors–are in traditional Japanese attire, while Orestes enters the stage in a T-shirt and shorts. Electra is scantily dressed in a slip, so that the siblings’ vulnerability becomes even more pronounced and the discrepancy between the ancient and the modern–both the traditional and its rejection–more manifest (McDonald 1992: 47). In addition, Clytemnestra’s white-faced avenging ghost mixes vestment elements from the Noh tradition with Japanese folklore. Once again, Suzuki instills elements of his native tradition into the equally heightened form of Greek tragedy: aesthetic stylization and a concern for the other-than human forces that guide humans’ lives meet in the ritual form of both tragedy and the Japanese Noh. Indeed, 10 as Allain aptly relates, ‘resurrected by Suzuki, Greek protagonists walked alongside the ghosts of noh’ (2002: 153). Some Conclusions In analysing contemporary performance of Greek tragedy, the following observation becomes clear: in order to be able to do justice to the director and the production, one must always take into account the time, place and specifics of reception. In other words, interpretations that felt irrelevant to one specific audience were enthusiastically received by another, seemingly serving the spectators’ particular socio-cultural circumstances. Therefore, the question of the ‘right’ or wrong ‘production’ and the ethics of directing should, if anything, be addressed in terms of context, which ultimately ‘conditions meaning’ (Hutcheon 2006: 145). Evidently, striking ideas and visual imagination can only work if they originate in the artist’s deeper connection to the world. It is this connection that holds the material together and breathes life into it. In examining innovative stagings of the Greeks, we are stunned at Suzuki’s cultural scope, Romeo Castelluci’s transcendental scenography, Robert Wilson’s ever-expanding colour palette, Ariane Mnouchkine’s exotic figures or Katie Mitchell’s mediascapes, to name but a few of the most radical directors worldwide. We are grateful for the beauty and the visual insights they provide for the old plays. This is when form deepens, magnifies and amplifies the original work, building worlds that transform the writer’s imagination into a moving sensory experience. No doubt, such encounters are fuelled by a burning desire to understand, to express, to connect. Fischer-Lichte has described the revised hierarchical structure between text and performance in ‘directors’ theatre’ in terms of Nietzche’s understanding of 11 ‘dismemberment,’ a kind of sparagmos, relating to a process of tearing apart the original text, in order for the performance to take shape (2005: 233-234). Within the postmodern freedom and tyranny of choice, one often notices a tendency to overcompensate meaning with form: On occasion, in their relentless pursuit of imagery and metaphor, experimental artists may become oblivious to whatever threatens their work’s deliberate, if hazy, abstraction, verging on cultural appropriation and or a-historicity. In such context-free performances, the desire to revive the universal elements of the story seems detached from any social or political discourse. But theatre cannot really claim absolution from memory or history. Given that the social, civil, and religious import of the Greek plays harbours a strong emotive value –the very texture of drama being intertwined in their cultural specificity— depoliticizing them by means of aesthetic filters divests them of a perspective at once historical and timeless, a reproach that many conceptualists have been systematically charged with. It also diminishes their ability to move; a fixation on perceptual frames without an underlying discursive exploration causes an obliteration of dramaturgical specificity, an erasure of metaphysical viewpoint; in effect, an undermining of experience as a critical re-evaluation of memory (Sidiropoulou 2014: 60). At the same time, one should also consider whether a form as open as that of tragedy could ever be made to fit the dicta of small-case circumstance. Greek director Theodoros Terzopoulos’ condemnation of the current directorial trend/ to bend tragedy’s structure and stature in order to create ‘plausible’ characters is worth noting. His conviction that ancient theatre cannot be turned into chamber drama/ is grounded on an awareness of tragedy as an ‘open form’: 12 [Tragedy] has several levels, which are extremely dense. We can only interpret few of them, but the greater part remains unexplored, adjusting itself to new social, political and human conditions. We can adjust the timelessness of wars, modernise it, transfer it to human situation, to the city, and other contemporary matters, such as the environment, to the issues of love and death, even to cloning; but we can never transcend certain principles that have to do with selfconcentration, the grand stature, the grand energy . . . because we can never whisper those issues by adapting them to the new circumstances. (Qtd in Karali 2008) Suzuki’s long-time collaborator and co-founder of SITI Company in the U.S., director Anne Bogart, thinks of plays as ‘little pockets of memory.’ She makes special reference to the Greek texts, describing how a director can use a play about hubris as a ‘chance to bring that question into the world and see how it looks at the time you’re doing it.’ Moreover, she understands artists’ fascination with revisiting old works to be part of the need to reclaim something that has been lost, ‘the sense that theatre has this function of bringing these universal questions through time.’ The attempt to globalize the local and temporalize the universal has been an instrumental force behind Suzuki’s theatre, an ability to construct powerful modern equivalents that will correspond to the heightened style of the classical work. In closing: It is no surprise that the lofty, enduring stature of tragedy, with its larger-than-life characters and the representation of forces beyond human comprehension has in one way or another become a viable medium for artists to comment on the absence of grandeur and heroics today. Essentially, as Suzuki argues, ‘theatre provides no relief. It makes us see. There is no way out because we no longer 13 have ideals strong enough.’ In rethinking the tragic spirit, revised forms can act as a kind of umbilical cord that can nourish the relationship between past and present. While in any directorial production of Greek tragedy it is still useful to ‘distinguish between deconstruction and provocation’ (Pavis 2013: 233), the question becomes how setting, time period, language, character portrayal and action can tune into new rhythms and be defined by new concepts, whose power to revise, update and render meaningful does not originate in the desire to merely shock, nor in a complacent attitude towards reception; concepts, which are constantly put into trial in order to both safeguard and further stretch the boundaries of interpretation when confronting a classic. In reality, as Tadashi Suzuki’s performances of tragedy have demonstrated, the Greeks are there to remind us that any new reading is ultimately both an opportunity and a gift. Thank you. 14 Works Cited Allain, Paul. The Art of Stillness. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002. Baeten, Elizabeth M. The Magic Mirror: Myth’s Abiding Power. Albany: State U of New York P., 1996. Barthes, Roland. ‘Putting on the Greeks.’ Critical Essays. Trans. Richard Howard. Evanston: Northwestern UP, 1979. Bogart, Anne. A Director Prepares: Seven Essays on Art in Theatre. New York: Routledge, 2001. Calvino, Italo. Why Read the Classics? (trans. Martin McLaughlin). New York: Vintage, 2000. Carruthers, Ian and Takahashi, Yasunari. The Theatre of Suzuki Tadashi. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2004. Cooper, Neil. ‘Tadashi Suzuki’s New Play Sets a Greek Myth in an Asylum’ The Herald August 10, 2012. Eco, Umberto. Postscript to the Name of the Rose. San Diego, CA: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1984. Fischer-Lichte, Erika. Theatre, Sacrifice, Ritual. Exploring forms of political theatre. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2005. Hutcheon, Linda. A Theory of Adaptation. New York: Routledge, 2006. Hall, Edith, Fiona Macintosh and Amanda Wrigley, eds. Dionysus Since 69. Greek Tragedy at the Dawn of the Third Millennium. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004. Hutcheon, Linda. A Theory of Adaptation. London and New York: Routledge, 2006. Laera, Margherita. Reaching Athens: Community, Democracy and Other Mythologies in Adaptations of Greek Tragedy. Frankfurt am Mein: Peter Lang, 2013. Martindale, Charles and Richard F., Thomas, eds. Classics and the Uses of Reception. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2006. Mitter, Shomit and Maria Shevtsova, eds. Fifty Key Theatre Directors. London: Routledge, 2005. Neely, Kevin. ‘Clytemnestra by Tadashi Suzuki’, Theatre Journal 39 (1987): 514516. Nietzsche, Friedrich. Birth of Tragedy and Other Writings. Trans. Ronald Speirs. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1999. 15 Pavis, Patrice. Contemporary Mise en Scene. Staging Theatre Today (trans. J. Anderson). London and New York: 2013. Revermann, Martin. “The Appeal of Dystopia: Latching onto Greek Drama in the Twentieth Century.” Arion, Third Series 16.1 (2008): 97-118. Print. Sanders, Julie. Adaptation and Appropriation. The New Critical Idiom. London and New York: Routledge, 2006. Sidiropoulou, Avra. ‘Mise-en-Scène as Adaptation’, Critical Stages 12, 2015. URL: http://www.critical-stages.org/12/mise-en-scene-as-adaptation/ (accessed 5 January 2016) ---. ‘Adaptation, Recontextualization and Metaphor. Auteur Directors and the Staging of Greek Tragedy’, Adaptation. Oxford Journals 8 (2014): 31-49. Steiner, George. Antigones. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989. Terzopoulos, Theodoros. Interview by Antigoni Karali. “Tragedy Needs Stature” [“Θέλει παράστημα η τραγωδία”]. Ethnos 29 June 2008. 16 17