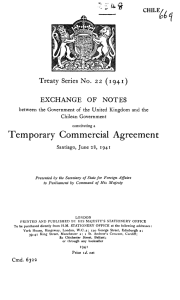

Polarization in the Chilean Party System

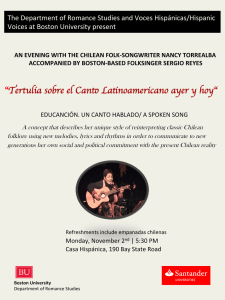

Anuncio