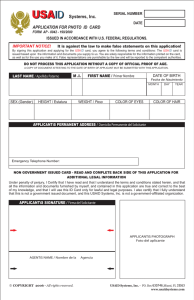

United States Agency for International Development

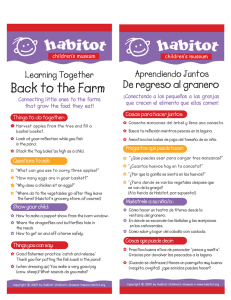

Anuncio