Eficacia de la Retroalimentación Formativa para Mejorar

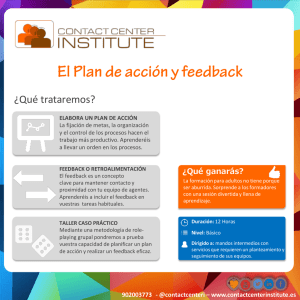

Anuncio