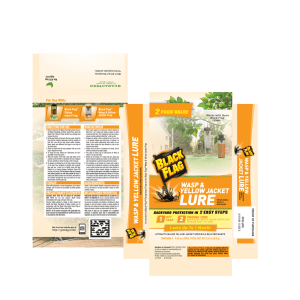

Stopping runaway IT projects Yukika Awazu Credit Administrator, UFJ Bank Limited, Chicago, Illinois (yukika_awazu@ufjbank.co.jp) Kevin C. Desouza Doctoral candidate, Department of Information & Decision Sciences, University of Illinois at Chicago (kdesou1@uic.edu) J. Roberto Evaristo Assistant Professor of Information & Decision Sciences, University of Illinois at Chicago (evaristo@uic.edu) A great number of IT projects seem to take on lives of their own, gobbling up valuable resources without ever reaching their objectives. But they can be tamed. Once managers understand the key reasons why projects become runaways, they can learn to analyze the early signs of escalation and decide whether, when, and how to pull the plug. Project management will never become an exact science, but the guidelines provided here can at least help move it into the realm of a disciplined art. Business Horizons 47/1 January-February 2004 (73-80) S ometimes, organizational success hinges on the efficient and effective management of projects— endeavors in which, according to Turner (1993), “human, material and financial resources are organized in a novel way, to undertake a unique scope of work, for a given specification, within constraints of cost and time, so as to achieve beneficial changes defined by quantitative and qualitative objectives.” Today we witness a great number of projects that seem to take on lives of their own, continuing to absorb valuable resources without ever reaching their objectives—in other words, runaway projects. The majority of information technology projects seem to fall into this category. Johnson (1995) cites various studies estimating that about 30 to 65 percent of software development projects become runaways. After surveying more than 8,000 IT projects, the Standish Group (1994) reported that 30 percent of them were canceled before attaining their objectives due to poor project management practices. The average canceled project in the United States is about a year behind schedule and at 200 percent of its estimated budget by the time it gets the axe. According to Jones (1994), efforts on canceled projects can make up as much as 15 percent of total US software expenditures, which amounted to as much as $14 billion in 1993. KPMG (1995) cites several key reasons for runaway projects: objectives not fully specified; bad planning and estimating; implementing new technology; inadequate or no project management methods; insufficient senior staff on the team; and poor performance by hardware or software suppliers. With such dreary statistics, any effort to understand and curtail the phenomenon of runaway projects is bound to be of interest to both executives and business academics. Like all projects, those involving IT begin with a definite goal. Resources are organized systematically and temporally to attain that goal, and a budget details the extent and scope of resources to be used. However, IT projects have peculiarities that tend to blow project management problems out of proportion. First, IT projects are riskier; 73 Y. Awazu et al. / Stopping runaway IT projects their unfinished products may have no value at all, whereas, say, a half-paved road is still usable and better than a non-paved one. Second, the field of IT has yet to mature. Firms must contend with a constant barrage of new IT products, tools, and technologies, and the management of these technologies is not even close to being a science. Managers who complain about being stretched too thin are nonetheless expected to manage projects that are charting new areas using tools still being developed and tested. Third, IT projects face much more pressure than traditional ones because they are still viewed by many as cost centers. They get bare minimum budgets compared to other organizational endeavors, with little room for slack or redundancy in design. Fourth, IT projects are not specific to a department or group; more often than not, they affect multiple departments and involve multiple stakeholders. Compromising on individual agendas to attain a global goal is not an easy task. At various times during a project, management must evaluate its health. Whenever the current resource usage exceeds the budgeted amount, the project is starting to “run away.” Rational interventions, such as halting the project or modifying requirements and resources to meet the budget, should prevent it from continuing on this disastrous course. But instead of such espoused rational behavior, the theory in use by many managers is to allow it to continue—as Brockner (1992) calls it, an “escalation of commitment.” Underscoring the above, we also have to account for bounded rationality. As Simon (1996) notes, at any given point a manager will not be able to examine all the relevant information for making a decision on a particular situation. So he is forced to “satisfice”—to obtain an outcome that is “good enough,” though perhaps not the best, based on past experience and the limited information he possesses or is able to process. For the most part, researchers have applied these various theories to the examination of runaway IT projects. But although “espoused theories” of the phenomenon have been developed, little if any work has been undertaken to articulate “theories of use.” In our opinion, this serves little practical purpose for managers who want to prevent and curtail escalating projects. So we propose an interactive, two-phase intervention set for software projects. Using a grounded theory research approach, we have developed this model through discussions with practitioners in ten software engineering organizations. We cannot guarantee its absolute generalizability, but preliminary feedback from practitioners attests to its suitability and applicability. In managing a project, the two most critical resources— time and cost—must be monitored throughout its life cycle (see Figure 1). At any point during the project, if the time to completion or the expected future expenses exceed that of the budget, its manager must contemplate the decision: “Do I let the project continue?” Runaway projects can be studied in two phases: pre- and post-escalation. Pre-escalation is when the project is still on the planned course but certain factors are swaying it toward failure; post-escalation is when the project has already COST Much research, especially in the behavioral sciences, has tried to explain why individuals commit to a failing course of action, even in the face of negative feedback. The three most salient explanations are as follows. First, Festinger’s theory of cognitive dissonance holds that decision makers intuitively focus on information that supports their point of view, due to the need for selfFigure 1 justification. Hence, project managers are less Life cycle of IT projects—three types of escalating projects likely to solicit or pay attention to negative information on a project’s status. Second, prospect theory maintains that individuals are risk-seeking Runaway Budgeted when choosing between two losing options but Runaway project: cost project: risk-averse when choosing between winning Time + Cost Cost options. Therefore, project managers faced with the choices of terminating a failed project or escalating commitment are more likely to escalate. Runaway Finally, according to agency theory, which deals project: with the relationship between the one who deleTime gates work (the principal) and the one who performs the work (the agent), agents will choose to execute decisions that maximize their own selfinterest at the expense of the principal due to Budgeted time information asymmetry. Hence, project managers are less likely to cancel escalating projects because it is not in their best interests, even though it is beneficial to the overall organization. TIME 74 Business Horizons 47/1 January-February 2004 (73-80) Y. Awazu et al. / Stopping runaway IT projects consumed resources in excess of the budget and the project manager continues to commit resources to it. There are two types of interventions managers can use in dealing with runaway projects: proactive and reactive. As Agre (1982) notes, a problem is not a problem until it is identified. Therefore, the first step—the proactive step—in On average, the project manager’s daily “information intake” is around 250 e-mail messages coupled with two dozen voicemails. improving project management is to identify potential issues that could compromise the ability to keep a project on time and within budget. Clearly, if an issue is identified before it becomes a real problem, a runaway situation stands a better chance of being averted. Once the project has begun to run away, its managers are forced to react to reality. It is important here to study the issues involved in pulling the plug on these runaways. Put another way, the first issue to contend with is: Why is it difficult to identify the signs of an impending runaway project? The second is: Why is it difficult to react rationally and terminate the project? Why is it hard to see the signs of a runaway project? A nything left unchecked that can run amok and contribute to project failure is a “sign” in this context. The list of potential signs is large. Most critical, though, we have to understand the reasons why the signs of a runaway may not be routinely identified in time. We were able to distill three major reasons: attention deficit, information overload, and managerial overconfidence. Attention deficit In the current age of multitasking, we seldom find project managers devoted to a single endeavor. On average, they tend to handle four or five concurrently running projects, with varying complexities and requirements. Hence, each project gets only a slice of their attention. As one project manager of a mid-sized software consulting firm in Chicago noted: Business Horizons 47/1 January-February 2004 (73-80) With the recent downsizing…those of us who are left have to carry much higher loads in terms of projects. Hence I am time starved,…as a result of which, I do not give each project enough attention. A manager who cannot attend all the meetings cannot take an integral part in project efforts. Thus, IT project managers often delegate most of the responsibility of “managing the project” to a senior business analyst or software engineer. But these individuals are too caught up in the development phases and micro details of the project to pay attention to such macro variables as Gantt charts and costs. Moreover, they are not trained well enough in project management methods to catch abnormalities and identify signs of potential failure. The lack of due attention leads to bounded rationality—the inability to identify potential issues. Information overload All the managers we interviewed admitted to falling prey to the information overload syndrome. With the rate of advancement in computing and its ubiquitous nature, managers are now bombarded with more information, and on a much more frequent basis, than ever before. Take the case of a project manager for a consulting firm based in Austin, Texas. On average, his daily “information intake” is around 250 e-mail messages coupled with two dozen voicemails, most of which have to do with the projects he is responsible for. In conjunction with executing his daily tasks at the company, he seldom gets through all the information bytes he receives during the day. So, like most managers, he employs a filtering tool that sifts through his inbox and sorts messages based on relevance and source. Thus, many messages related to a project either go unread or experience delays in being read. In fact, those from the “front-line” members of a project team are attended to last, since a manager’s first responsibility is to his fellow project managers and his supervisor. Messages from the front lines are often the first indicators that a project is in trouble. By ignoring them or delaying attending to them, the manager falls victim to the overload syndrome, making his project more vulnerable to becoming a runaway. Managers in overload situations are likely to act under conditions of bounded rationality and be forced to ignore important signals for issue detection. To compound the problem, their cognitive dissonance may lead them to ignore even those signals that do pass through the information overload gate. The overconfidence trap We have all been guilty of overestimating our abilities, heuristics, intuitions, and gut feelings. As one manager explained: 75 Y. Awazu et al. / Stopping runaway IT projects I have been at this organization for over ten years and have managed [well] over 100 projects…I think no project plan can account for my experience in running projects.…Which should I rely on, an Excel sheet or my [gut] feelings to call the shots?…Computer tools are meant to aid me in my decision, not overturn or force me into a decision. Most managers admit that one reason they fail to detect and process signals about impending project failures is an innate chauvinism about their abilities. Hammond, Keeney, and Raiffa (1998) refer to this as the “overconfidence trap.” Prietula and Simon (1989) point out that instead of following rules and procedures, experts are more inclined to rely on heuristics for task execution. Similarly, managers seldom follow through with all necessary analyses and protocols at each stage of a project evaluation; they are more likely to base their judgments of the project’s health by relying on their intuition. As with cognitive dissonance, this often leads them to ignore facts that convincingly indicate a project in trouble. Why is it hard to react to an identified sign? A fter the telltale signs have been identified, they may or may not lead to a full-fledged runaway problem. When they do, there are still plenty of reasons why managers do not act on them. Moreover, even issues that do not become full-fledged problems still need corrective action. The key reasons for not reacting rationally to signs are conforming evidence, the status quo, sunk costs, power battles, and, surprisingly, harmony. Conforming evidence The conforming evidence trap is a variant of the cognitive dissonance theory, or the need for self-justification, in which conflicting information is given little attention or ignored altogether. Our results attest to the saliency of this trap in preventing the plug from being pulled on a runaway project. The tendency to “hear only what you want to hear” is the pivotal governing cause. Though no one willingly admits to falling victim to this trap, we deduced its prominence through our discussions with project managers and by evaluating secondary evidence. One manager remarked that the reason he did not stop a certain project earlier was because he was presented with a statement that showed the team was on target. But when we viewed the statement, it was clear to us that the manager had not seen it in total—the project summary had a series of footnotes from a senior software engineer notifying the manager of the need to shell out an additional $50,000 for unplanned expenses. Of course, another issue 76 here is information asymmetry: the subordinate may not have wanted to display problems prominently because of the consequences, so he passed the buck to the principal, who was already operating under conditions of bounded rationality and cognitive dissonance. Maintaining the status quo Decision makers have strong biases toward making judgments that meet the status quo. Going against it means opening themselves to criticism and risking damage to their egos. They rationalize their decisions to meet common norms because it is a much safer route. Thus, managers opt to let projects run away rather than admit they have made a mistake. Not surprisingly, in firms where the notion of failing in an assignment was heavily frowned upon, managers were less likely to admit their fault. We also saw evidence for the “mum” effect, in which the team members of a runaway project were reluctant to blow the whistle on the project manager and speak out. A key reason for this is the current uncertainty in the IT marketplace. One software engineer reported: If the economy were in better shape, many of us would have left…as half of the projects we work on are viewed down on.…If I speak out, I’ll be on the street. Both project managers and team members are thus guilty of maintaining the status quo and allowing projects to run away from them. There are other related issues, such as the difficulty of admitting to a mistake because of the stigma such an event carries in a firm. Delaying the problem, or at least hoping it will go away or be inherited by someone else, is a valid strategy under that premise. There is also the likelihood that certain managers may engage in post hoc changes to the project’s assumptions or original conditions. It is well known that updates to project tracking software are often made late or not at all. Hence, one can manipulate the “portrayed reality” of a project by the information entered into the project management software. The problems shown at the time of updating can be (fictitiously) alleviated by changing the original numbers, a practice occasionally conducted to delay drawing attention to an ailing project. A final consideration is annual merit reviews, which decide bonuses, promotions, and tenure. We found that a project manager is more likely to keep spending on a runaway project in the last quarter of the year, rather than let his current year’s review be affected. Thus, keeping up with the status quo can be summed up as the continued support of a project until its resources run dry due to the procrastination of dealing with reality. In all of the above cases, cognitive dissonance plays an extremely important role in explaining the resulting escalation of commitment. Business Horizons 47/1 January-February 2004 (73-80) Y. Awazu et al. / Stopping runaway IT projects Sunk costs A common belief among project managers, even in the face of mounting losses, is, “We’ve already invested in it so let’s follow through on it.” However, runaway projects, regardless of continued investment, are never going to become profitable. Because many managers are evaluated on the percentage of projects they complete, they see project termination as a big negative. In support of previous research on this sunk costs trap, we found that decision makers are less likely to continue on a failed project if they are given alternative projects in which to invest. But in reality, such flexibility is seldom granted to project A common belief among project managers, even in the face of mounting losses, is, “We’ve already invested in it, so let’s follow through on it.” managers. They are allotted a fixed budget, and the movement of funds between projects is much easier said than done. Hence, a project manager may rationalize his continued commitment to a failed action until his pot of resources runs dry. This also extends the time for having to face the reality of failure. Power battles When two or more decision makers of equal power and status run into conflict, their desire is to protect their agendas at all costs. Hence, project management can turn into a power battle. Analyses and decisions are seldom made in the project’s interests; they are made to protect the egos of the decision makers. What transpires is a finger-pointing, head-butting game. One manager sends his analysis to his counterpart, who seldom pays any attention to the details of it, instead sending it back with his own analysis, and so on. Each one feels that the other’s analysis is based on ego rather than on hard facts. This constant moving of documents continues until someone intervenes in the project or the resources run dry. Harmony The trite opposite of the power battle trap is when project members like or respect their peers and try not to hurt their feelings by telling them they are following the wrong course of action and must quit. An outcome of falling into such a trap is that the project leaders conduct a series Business Horizons 47/1 January-February 2004 (73-80) of harmonious meetings in which everyone is nice to each other, thereby reinforcing bad decisions. It also leads to a variant of the bystander effect, in which one waits for one’s peer to bring up the thought of axing the project and/or take charge of its termination. One manager put it well: “I was waiting for Jack to call the shot. He’s a year senior to me and I respect his judgment on such matters.” Managerial interventions S o what can managers do to keep from falling victim to these difficulties, both when identifying issues and when making decisions on an identified problem? We present a set of recommendations that can help alleviate some of these concerns and reduce the occurrence of runaway projects. 1. Create checks and controls. A critical problem in issue identification is that incentives for detecting issues are not clearly stated. In fact, managers may actually receive disincentives to identify issues because the problems they unearth could point toward decisions that would harm their standing in the organization, or others’ perceptions of their competence. Therefore, the project team must create formalized checks and controls that de-personalize issue identification and eliminate the risk of “shooting the messenger.” Without the potential of becoming a scapegoat, a manager has more incentive to identify issues before they get out of control. Having checks and balances is beneficial for another reason: As one moves up the ranks, rewards and compensations are not based on the activities one completes but on how profitable one’s sector or department has been. Thus, it is in the best interest of senior managers and vice presidents to keep close tabs on their project managers and prevent runaways. 2. Do not let project managers become overburdened. Contrary to popular wisdom, IT advancements generally make the job of project management harder rather than easier. We sympathize with project managers who have to manage more than three projects concurrently. Moreover, most of these managers are administrators in some role— department heads, product development specialists, even vice presidents. Having to handle administrative tasks as well as project tasks makes it impossible for them to get out of the attention deficit trap. Companies can take some of the load off of project managers by delegating their more general tasks to the HR or department managers and allowing them to focus exclusively on their project endeavors. Another option is to hire and train more employees in project management methods. These 77 Y. Awazu et al. / Stopping runaway IT projects individuals can then be called upon to lead projects as warranted by organizational endeavors. 3. Manage overload and attention. To manage the information overload syndrome, one has to either increase information stream resources or deal with lower volumes of information. Most managers are starved for the right information at the right time to conduct actions. But getting it to them can be difficult; nor does it ensure that the right decision will be executed. Each project should have a designated “information manager” whose task would be to assimilate information and data from various entities in the project and make it presentable in a form that is actionable. The information manager could be a human, or it could be a machine— sort of like a car dashboard, which shows the car’s vital signs at a glance. Project managers can then act on the right information at appropriate time intervals. 4. Mitigate overconfidence and the bias for conforming evidence. Alleviating these two traps calls for a change in managerial behavior. We recommend Ann Langley’s 1995 article, “Between ‘Paralysis by Analysis' and ‘Extinction by Instinct”; it does an excellent job of highlighting how overreliance on heuristics and instincts can be devastating while being overly cautious serves little value. We would add only one more intervention: Again, have checks and balances. Project managers are often let loose on their own to run the show, which can be a double-edged sword. It may promote ease in decision making through the decentralization of authority. But an executive who has, say, 10 or 15 project managers reporting to him may be detached from the daily operations of each project, which prevents him from being an effective leader of his constituent project managers. The lack of supervision will lead to issues of overconfidence and conforming evidence going unchecked. A firm can also mitigate the conforming evidence trap by having another pair of eyes examine project details, logs, and performance. 5. Formalize channels of dissonant information. Today we have formalized and institutionalized searches for information that clearly supports projects, hence creating a rosy picture. The counterweight to this is the concurrent institutionalization of the search for negative pieces of information. The fact that both are institutionalized again creates the acceptance of issue identification, even when that affects a firm or an individual negatively. Project managers should be challenged to search for negative or dissonant information in their assignments. Moreover, employees that provide such information should be rewarded rather than shunned or penalized. 78 6. Listen to the whistles. One sure way to prevent a project manger from going along with the status quo and falling into the sunk costs trap is to encourage whistle-blowing. Rather than having a negative connotation, whistle-blowing is a means to bring necessary attention to a failing project. We like to think of it as an “SOS” (“Save Our Souls”) signal. Each Setting up a captain and a cocaptain at the outset prevents power struggles and encourages each of them to serve as a check and balance for the other. member of the project team needs to be able to use such a signal to bring attention to an impending catastrophe and save the project. An SOS signal is good only if people take notice, so a reward system must encourage saving resources by stopping runaways. Moreover, project managers need to be rewarded for the money they save when resources are reallocated. 7. Stimulate harmonious battles. The notion of “harmonious battles” may seem like an oxymoron, but it merits attention. A project should be headed by a single individual. Having two or more leaders with equal power and control of resources creates a fertile environment for runaways. If a project needs the expertise of two project managers of the same caliber, a clear decision needs to be made at the outset as to which has responsibility over the project’s fate. This is like commanding an aircraft. Even though both the pilot and the co-pilot are individuals of significant experience who respect each other, the pilot is in charge of the flight. This is not to say that at some time in the near future, when the two of them serve on a different flight mission, their roles may be switched. Setting up a captain and a co-captain at the outset prevents power struggles and encourages each of them to serve as a check and balance for the other. The learning factor A lthough the first line of defense will always be the implementation of better issue detection mechanisms, a close second is to promote learning on how to deal with runaway projects as they happen. Here we propose a set of behaviors that in the long run will Business Horizons 47/1 January-February 2004 (73-80) Y. Awazu et al. / Stopping runaway IT projects reinforce the learning of skills that improve project managers’ ability to deal with problems. 1. Make post hoc changes impossible. This may be as simple as fixing/freezing the system in which the original forecasts were created. The larger view to this is the need to create a careful control system that can point out when changes in the actual processes start to override those that were predicted or budgeted. The European Space Agency (ESA) created a project management software program that is deeply connected to its billing system. An outsourcer can only bill for a milestone that has been completed and marked as such in the software. Changes to a project can be made, but they require consequent changes in the legal contracts. Only then will they be depicted in the billing system. This gives managers an opportunity to improve their problem-solving skills by getting immediate feedback on which actions are best and what is the most likely course of action to bear fruit over the long run. 2. Decrease the perceived cost of mistakes. Certain organizations understand that the secret of great creativity is the accepted cost of making mistakes. This is the case with 3M, where the organizational culture fosters innovation. The development of the Post-It Note has drawn much attention for the chain events that led to the successful product. Conversely, a firm in which mistakes are frowned upon or punished will tend to have members who are afraid of getting caught “erring” and who stay with the chosen course of action, even if it is a much worse option in the long run. 3. Improve the ease of information sharing. An obvious problem is that although parts of the IT firm, particularly line programmers, may already know that their component of the project will be delayed, the project manager may not be aware of the ripple effect on other components. Part of the reason for such a shortcoming is that information is not necessarily or easily shared. The solution is to enforce a good knowledge management tool that documents such milestones and reasons for delays. In fact, ESA’s Web-based solution (efis.esa.int) is also a knowledge management tool rolled into its project management and invoicing systems. Managers anywhere in the firm are able to understand why a certain project is late or over budget because of the requirement that all information be documented for bills to be paid. In fact, outsourcers have direct access to parts of the system to keep all their information up-to-date. Besides technology mechanisms, people-based mechanisms such as the steering of informal networks are also beneficial for informa- Business Horizons 47/1 January-February 2004 (73-80) tion sharing. As Desouza (2003) reports, a lot of knowledge and information travels through the grapevine, so the use of coffee rooms and game rooms has become popular for fostering the exchange of information and tacit knowledge. These could also be valuable avenues to disseminate lessons learned about runaway projects. P roject management will never be an exact science. Our intention here is to provide guidelines that can at least help move it into the realm of a disciplined art. All of the interventions discussed here could be applied in the proactive or reactive phase of a project. Ideally, if applied proactively, they can alleviate the need for being reactive. Two interventions, however, deserve special attention in the proactive stage. First is managing the information load problem. The information explosion is not expected to level off or slow down. Hence, firms must realize that managing information about, from, and in projects needs to be undertaken systematically. Second is sending out SOS signals. Drawing on its traditional meaning, an SOS signal is valuable only if souls can be saved before death. Acting on it after a calamity or catastrophe has occurred and damage is complete is obviously of little value. At best, the firm can conduct a postmortem to learn project management lessons for the future. ❍ References and selected bibliography Agre, Gene P. 1982. The concept of problem. Educational Studies 13/2 (Summer): 121-142. Brockner, Joel. 1992. The escalation of commitment to a failing course of action: Toward theoretical progress. Academy of Management Review 17/1 (January): 39-61. Desouza, Kevin C. 2003. Facilitating tacit knowledge exchange, Communications of the ACM 46/6 (June): 85-88. Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. 1989. Agency theory: An assessment and review. Academy of Management Review 14/1 (January): 57-74. Festinger, Leon. 1957. A theory of cognitive dissonance. Evanston, IL: Row Peterson. Garland, Howard. 1990. Throwing good money after bad: The effect of sunk costs on the decision to escalate commitment to an ongoing project. Journal of Applied Psychology 75/6 (December): 728-731. Hammond, John S., Ralph L. Keeney, and Howard Raiffa. 1998. The hidden traps in decision making. Harvard Business Review 76/5 (September-October): 47-58. Harrison, Paul D., and Adrian Harrell. 1993. Impact of “adverse selection” on managers’ project evaluation decisions. Academy of Management Journal 36/3 (June): 635-643. Johnson, Jim. 1995. CHAOS: The dollar drain of IT project failures. Application Development Trends 2/1 (January): 41-47. Jones, Capers. 1994. Assessment and control of software risks. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Yourdon Press. Kahneman, Daniel, and Amos Tversky. 1979. Prospect theory: An analysis of decisions under risk. Econometrica 47/2 (March): 263-291. 79 Y. Awazu et al. / Stopping runaway IT projects ———. 1982. The psychology of preferences. Scientific American 246/1: 160-173. Keil, Mark. 1995. Pulling the plug: Software project management and the problem of project escalation. MIS Quarterly 19/4 (December): 421-447. ———, Paul E. Cule, Kalle Lyytinen, and Roy C. Schmidt. 1998. A framework for identifying software project risks. Communications of the ACM 41/11 (November): 76-83. Keil, Mark, and Joan Mann. 1997. The nature and extent of IT project escalation: Results from a survey of IS audit and control professionals. IS Audit & Control Journal 1: 40-48. ———, and Arun Rai. 2000. Why software projects escalate: An empirical analysis and test of four theoretical models. MIS Quarterly 24/4 (December): 631-664. Keil, Mark, and Ramiro Montealegre. 2000. Cutting your losses: Extricating your organization when a big project goes awry. Sloan Management Review 41/3 (Spring): 55-68. KPMG. 1995. Runaway projects—cause and effect. Software World 26/3: 3-5. Langley, Ann. 1995. Between “paralysis by analysis” and “extinction by instinct.” Sloan Management Review 36/3 (Spring): 63-76. Neumann, Michael, and Rajiv Sabherwal. 1996. Determinants of commitment to information systems development: A longitudinal investigation. MIS Quarterly 20/1: 23-54. 80 Nonaka, Ikujiro, and Hirotaka Takeuchi. 1995. The knowledgecreating company. New York: Oxford University Press. Prietula, Michael J., and Herbert A. Simon. 1989. The experts in your midst. Harvard Business Review 67/1 (January-February): 120-124. Simon, Herbert. 1996. The sciences of the artificial. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Smith, H. Jeff, Mark Keil, and Gordon Depledge. 2001. Keeping mum as the project goes under: Toward an explanatory model. Journal of Management Information Systems 18/2 (Fall): 189-227. Standish Group. 1994. Charting the seas of information technology. Dennis, MA: The Standish Group. Staw, Barry M., and Jerry Ross. 1978. Commitment to a policy decision: A multi-theoretical perspective. Administrative Science Quarterly 23 (March): 40-64. Turner, J. Rodney. 1993. The handbook of project-based management. New York: McGraw-Hill. Whyte, Glen. 1986. Escalating commitment to a course of action: A reinterpretation. Academy of Management Review 11/2 (April): 311-321. ———. 1991. Decision failures: Why they occur and how to prevent them. Academy of Management Executive 5/3: 23-31. Business Horizons 47/1 January-February 2004 (73-80)