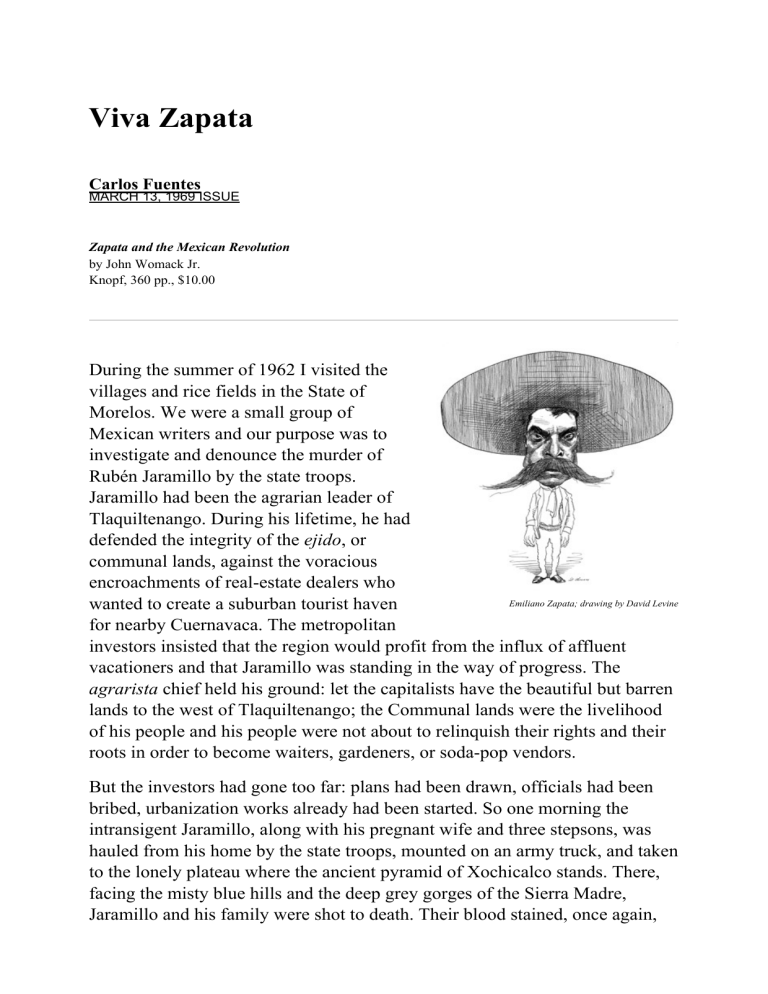

Viva Zapata Carlos Fuentes MARCH 13, 1969 ISSUE Zapata and the Mexican Revolution by John Womack Jr. Knopf, 360 pp., $10.00 During the summer of 1962 I visited the villages and rice fields in the State of Morelos. We were a small group of Mexican writers and our purpose was to investigate and denounce the murder of Rubén Jaramillo by the state troops. Jaramillo had been the agrarian leader of Tlaquiltenango. During his lifetime, he had defended the integrity of the ejido, or communal lands, against the voracious encroachments of real-estate dealers who Emiliano Zapata; drawing by David Levine wanted to create a suburban tourist haven for nearby Cuernavaca. The metropolitan investors insisted that the region would profit from the influx of affluent vacationers and that Jaramillo was standing in the way of progress. The agrarista chief held his ground: let the capitalists have the beautiful but barren lands to the west of Tlaquiltenango; the Communal lands were the livelihood of his people and his people were not about to relinquish their rights and their roots in order to become waiters, gardeners, or soda-pop vendors. But the investors had gone too far: plans had been drawn, officials had been bribed, urbanization works already had been started. So one morning the intransigent Jaramillo, along with his pregnant wife and three stepsons, was hauled from his home by the state troops, mounted on an army truck, and taken to the lonely plateau where the ancient pyramid of Xochicalco stands. There, facing the misty blue hills and the deep grey gorges of the Sierra Madre, Jaramillo and his family were shot to death. Their blood stained, once again, the carved frieze of the plumed serpent that devours its own tail around the base of the Toltec temple. PUBLICIDAD Jaramillo’s secretary received us in a simple brick hut. He was a bald, middleaged man with a big curly moustache and the face and hands of a smooth brown Buddha. He was indistinguishable from the campesinos around him, except for two details that marked him as a literate man: he wore, in the hot, vibrant night, a black waistcoat, and a gold-plated ballpoint pen conspicuously stuck out of his shirt pocket. He was gentle and proud, sad and firm in his speech and manner. Yes, he had been warned by the state officials to lay off. He knew who was responsible: a well-known and virtually untouchable Mexico City financier, in collusion with the Governor of Morelos, who, by the way, had been involved in the killing of Emiliano Zapata forty-three years before. We all knew that the only man finally responsible for the actions of the Mexican army was the President of the Republic. Yes, he would probably have to flee and go into hiding. The real-estate people would probably win this time. We did not try to hide our outrage; he remained serene. He looked at us, at our city clothes, at our dove-blue Renault parked near the tropical veranda full of hammocks and flower pots. “No coman ansias,” he murmured with wry sympathy,… This is exclusive content for subscribers only – subscribe at this low introductory rate for immediate access! SUBSCRIBE FOR $1 AN ISSUE Unlock this article, and thousands more from our complete 55+ year archive, by subscribing at the low introductory rate of just $1 an issue — that’s 10 digital issues plus six months of full archive access plus the NYR App for just $10. If you are already a subscriber, please be sure you are logged in to your nybooks.com account. © 1963-2019 NYREV, Inc. All rights reserved.