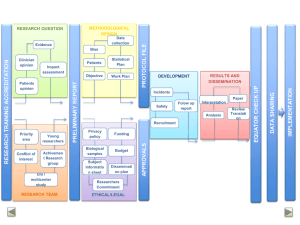

Physical Therapy Interventions for Parkinson Disease Robyn Gisbert and Margaret Schenkman PHYS THER. Published online November 25, 2014 doi: 10.2522/ptj.20130334 The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, can be found online at: http://ptjournal.apta.org/content/early/2014/11/25/ptj.20130334 E-mail alerts Sign up here to receive free e-mail alerts Online First articles are published online before they appear in a regular issue of Physical Therapy (PTJ). PTJ publishes 2 types of Online First articles: Author manuscripts: PDF versions of manuscripts that have been peer-reviewed and accepted for publication but have not yet been copyedited or typeset. This allows PTJ readers almost immediate access to accepted papers. Page proofs: edited and typeset versions of articles that incorporate any author corrections and replace the original author manuscript. Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by Alan Daniel on November 29, 2014 Running Head: Physical Therapy Interventions for Parkinson Disease <LEAP> Linking Evidence And Practice Physical Therapy Interventions for Parkinson Disease Robyn Gisbert, Margaret Schenkman R. Gisbert, PT, DPT, Physical Therapy Program, School of Medicine, University of Colorado, 13121 E 17th Ave, Mail Stop C244, Aurora, CO 80045 (USA). Address all correspondence to Dr Gisbert at: robyn.gisbert@ucdenver.edu. M. Schenkman, PT, PhD, FAPTA, Physical Therapy Program, University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Denver, Colorado. [Gisbert R, Schenkman M. Physical therapy interventions for Parkinson disease. Phys Ther. 2015;95:xxx–xxx]. ©2014 American Physical Therapy Association Publish ahead of print xxxx Accepted: November 13, 2014 Submitted: July 19, 2013 Acknowledgments Dr Schenkman provided concept/idea/research design. Both authors provided writing. DOI:10.2522/ptj.20130334 Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by Alan Daniel on November 29, 2014 1 Abstract <LEAP> highlights the findings and application of Cochrane reviews and other evidence pertinent to the practice of physical therapy. The Cochrane Library is a respected source of reliable evidence related to health care. Cochrane systematic reviews explore the evidence for and against the effectiveness of appropriate interventions – medications, surgery, education, nutrition, exercise – and the evidence for and against the use of diagnostic tests for specific conditions. Cochrane reviews are designed to facilitate the decisions of clinicians, patients, and others in health care by providing a careful review and interpretation of research studies published in the scientific literature. Each article in this PTJ series summarizes a Cochrane review or other scientific evidence on a single topic and presents clinical scenarios based on real patients or programs to illustrate how the results of the review can be used to directly inform clinical decisions. This article focuses on an adult patient with relatively early Parkinson’s disease. Can physiotherapy intervention strategies improve his physical functioning, and help him to reach his goal of engaging in an exercise program to prevent decline related to progressive PD. Background /Introduction Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a multifaceted neurodegenerative disorder affecting both motor and non-motor function. 1,2,3 PD is considered a disorder of the basal ganglia, because of its effect on the transmission of signals from the basal ganglia (BG) to the thalamus for roles in voluntary movement (including initiation, execution, and termination), cognition, and emotion. One of the major consequences of PD is degeneration of the substantia nigra of the midbrain which is the trigger for the abnormal signaling from the BG. The cardinal signs are tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia, and postural instability. Other motor symptoms include difficulty with motor planning and dual task performance.3 In addition, this disorder leads to a wide range of non-motor symptoms that could potentially affect the individual’s quality of life and also his or her participation in exercise. Approximately 1% of Americans over the age of 60, and an estimated 4% of the oldest Americans, are now diagnosed with PD. This prevalence is anticipated to double by 2030. 4 The mean age of initial diagnosis is around 60, 5 although a type of young onset PD can occur and diagnosis also can occur in late life. In most cases, there is no known cause of the disorder (i.e., it is idiopathic). People with PD often are categorized by Hoehn and Yahr (H&Y) stages (from 1-5) with Stage 1 indicating only minor symptoms and Stage 5 indicating the person is completely disabled and typically is confined to a bed. 6 Presentation of symptoms varies among individuals. Although there is a spectrum of presentation, two specific subtypes of have been identified with distinct clinical features and with different implications for prognosis. Specifically, PD is differentiated into two forms: tremor-predominant and postural instability and gait difficulty (PIGD). 7,8 The mainstay of intervention for people with PD of all stages is medical management including pharmacological options in early stages and surgical options (e.g., Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by Alan Daniel on November 29, 2014 2 deep brain stimulation, DBS) in later stages.1 Common pharmaceutical approaches include dopamine replacement, dopamine agonists, inhibitors of dopamine metabolism, and anticholinergic agents. In the past 15 years, a number of investigations have demonstrated positive outcomes from physical rehabilitation for people in early and midstages of PD. 9,10,11 Some of the intervention approaches are framed around improvements of direct consequences of PD (e.g., difficulty with dual task performance), others focus on sequelae (e.g., strength, flexibility, aerobic conditioning), and some are more global, addressing a variety of underlying impairments.6,12,13 Over the past decade, a number of reviews and systematic reviews have consistently suggested physical intervention is beneficial for people with PD.9,10,11,12 However, most of the reviewed studies were relatively small, and not of strong methodological quality. Given the burgeoning number and increasing quality of more recent studies, Tomlinson et al conducted a systematic review of the literature up to December 2010, published in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2012. 14 This review was conducted as a follow up to the Cochrane review published in 2001 and only included trials that compared physiotherapy interventions to either placebo or no intervention. A total of 33 trials were selected for review with 37 comparisons. Of these 33 trials, 29 compared physiotherapy intervention to no intervention and 4 to placebo intervention. A total of 1518 participants were included. They were of any duration of PD, any age, any drug therapy and any duration of physical therapy treatment. The trials were categorized as follows: general physical therapy (5), exercise (12), treadmill (7), cueing (7), dance (2), and martial arts (4). The number of treatment hours varied widely across studies (4.5 to 72), as did the number of weeks (2 to 52). Information was not provided regarding whether home programs were included in the protocols. Not all interventions were delivered by a physiotherapist. Tomlinson et al14 concluded that the risk of bias of included trials has improved since the 2001 Cochrane review; however improvement still is needed in both implementation and reporting. For example, the size of the studies is larger (about 50 participants compared with 25 in 2001). However, only 7/33 studies used the United Kingdom Brain Bank Criteria, which is the standard for diagnosing PD. Assessors were blinded in only 64% of the studies, and compliance was reported in only a third of the studies. Follow-up was short-term (usually about 3 months). A large number of outcome measures were used across these studies, including self-report and performance-based measures. Many of the measures related to balance, gait, and falls, although measures also were included of overall symptoms, quality of life, and disability. Of the measures included in the studies, there was sufficient data for a meta-analysis of 18 outcomes. Take-Home Message Based on their review, the authors concluded that significant short-term benefits are obtained with physiotherapy intervention on the following outcome measures: Twoand six-minute walk tests, walking velocity, step length, Timed Up and Go test (TUG), Functional Reach (FR) test, Berg Balance Scale (BBS), and Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale, UPDRS (Total, ADL, and Motor scores) (Tab. 1). Of these only the Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by Alan Daniel on November 29, 2014 3 improvements seen for walking velocity, BBS, and UPDRS scores were judged to be at levels of clinical importance. Post-intervention between group differences were small but judged by the review authors to be clinically meaningful. The authors compared improvements obtained by different intervention approaches and concluded they were small, supporting the notion that any of the interventions can lead to relatively comparable outcomes on these key measures. However, they cautioned that these were indirect comparisons; direct comparisons between intervention approaches are needed. Improvements also were demonstrated for other walking outcomes such as cadence and stride length. However these differences were not judged to be clinically meaningful. Nor was there a significant difference between the data from those receiving physiotherapy interventions and those in the control groups for falls or patient-rated quality of life. Case # XX: Applying evidence to a patient with early stage Parkinson’s disease Can physical therapy intervention help this patient? Mr. Jennings, a 54 year-old financial planner currently in H&Y Stage 2, was diagnosed with PD four years ago. His symptoms began seven years ago with weakness and tremor on his left side. He had not received prior physical therapy for PD. Medications and supplements included: pramipexole, selegiline and amantadine, CoQ10, a multivitamin and omega 3 fish oil. He had no significant comorbid conditions. His goal was to engage in a therapeutic exercise program to prevent decline related to PD. Mr. Jennings denied falls but reported feeling stiff, moving slowly, and being concerned about balance and walking, particularly in crowded environments. The physical therapy evaluation included measures of function and assessment of underlying impairments that could limit current or future abilities with balance and gait. A number of these measures were reported in the Cochrane Review including the Timed Up and Go, Functional Reach, and six- minute walk tests. Additional measures of balance and gait included the Five Times Sit to Stand test (FTSST) and the Functional Gait Assessment (FGA). 15 His score of 25/30 on the FGA indicated a mild fall risk. He was able to ascend and descend a full flight of stairs without use of a railing, indicating good lower extremity strength. This was further confirmed by his ability to perform the FTSST in 10 seconds and without use of hands. On clinical examination, cardinal signs of PD were evident, including resting tremor observable in his left hand, bradykinesia (limbs and whole body movements), and mild rigidity (limbs and trunk) that increased when he performed a cognitive dual task during passive range of motion. Mr. Jennings’ sitting posture was characterized by a posterior pelvic tilt and he stood with mild thoracic kyphosis. Both postures were somewhat flexible, suggesting potential for remediation. Functional Axial Rotation (FAR) was measured. This test quantifies the combined movements of multiple spinal regions, when a seated subject turns as far as possible without unweighting the pelvis. FAR was asymmetric and limited to 103° right and 97° left. This contrasts with data from 18 men ages 40-59 for whom FAR (mean, SD) was 117.9° (14.2) (Schenkman, unpublished). Lastly, Mr. Jennings had a PDQ-39 Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by Alan Daniel on November 29, 2014 4 Questionnaire summary index score of 5.1, indicating mild impact of PD on his quality of life. 16 How did the physical therapist apply the results of the Cochrane Review to Mr. Jennings? Mr. Jennings’ physical therapist posed the following question: Will a physical therapy program (compared with no treatment) improve physical functioning of a 54 year old man with Hoehn and Yahr Stage 2 of PD? Findings from the Cochrane systematic review completed by Tomlinson and colleagues were applied using the PICO (Patient, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) approach as follows: Patient. The review included people with PD who were in H&Y stages of 1-4 (mean stage of 2.4), mean age of 67, and six years post diagnosis. Mr. Jennings was in Stage 2, was younger than the mean (age 54), and had been diagnosed for four years. Thus Mr. Jennings fit into the overall criteria, but was younger and had the diagnosis for less time than the mean of the people in the studies reported. Intervention. The studies reported in the review included interventions categorized as general physical therapy, exercise, treadmill, cueing, dance, and martial arts (Tab. 1). The strategies chosen for Mr. Jennings, based on his individual impairments and his goal of preventing decline associated with aging and PD, were most similar to those categorized as general physical therapy and exercise. Specifically, his intervention included progressive resistive exercises (PREs), aerobic conditioning, balance reeducation and flexibility training using the axial mobility program. 17 In contrast to most of the studies, much of his plan of care was implemented with a home exercise program. With regard to dose, Mr. Jennings was seen for six physical therapy sessions (45-60 minutes each) over eight weeks, consistent with the lowest doses reported. To encourage adherence to home exercise, the patient and therapist stayed in contact through email. The patient submitted exercise logs, asked questions, and received feedback and encouragement. Comparison and alternate approaches. The review compared physical therapy intervention strategies to placebo control or no intervention. Mr. Jennings had not been exercising. Based on the review, it appeared that a variety of physical therapy approaches could benefit Mr. Jennings. Decisions regarding which specific elements to include among the various intervention possibilities were determined by Mr. Jennings’ specific underlying impairments coupled with his preferences. For Mr. Jennings, it was deemed important to improve his axial mobility. He had limitations in FAR and reported stiffness as a concern. Furthermore, one of his goals was to prevent declines in flexibility and function while aging with PD. Thus axial mobility was a significant component of his exercise program. Mr. Jennings was offered dance as an option for treatment, however he was not interested. He had home exercise equipment (i.e., treadmill and weight machines) and expressed a desire to learn how to exercise with his home gym equipment. It is difficult to make direct comparisons to the studies reviewed, as they varied widely, both in terms of dose and timing of the interventions. Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by Alan Daniel on November 29, 2014 5 Outcomes. The review concluded that all interventions, including the general physiotherapy interventions and exercise trials, demonstrated small, short-term beneficial changes for people with PD for gait, balance, and/or functional mobility measures. Some of the outcome measures used with Mr. Jennings were consistent with those reported in the review. How well do the outcomes of the intervention provided to Mr. Jennings match those suggested by the systematic review? The interventions provided for Mr. Jennings were most similar to those in the general physiotherapy and exercise trials. Tomlinson et al. reported significant improvements in FR with data from the exercise and cuing groups and in the TUG with data from the exercise, cuing, dance and martial arts groups. This participant’s improvements in balance, as evidenced by the FR and TUG tests, were at the high end of the changes reported by Tomlinson et al. Only limited data are available for the MCID of measures in PD and predominantly are from one study to date. The data reported may be from much more impaired individuals as the changes noted (e.g., 9 cm in forward FR, 11 sec for TUG) and would be improbable for Mr. Jennings, given his baseline status. Mr. Jennings’ six minute walk change score met the criteria of 50 m as the MCID reported for a variety of individuals with a variety of cardiopulmonary diagnoses. 18 Insert Table 2 about here. Three outcomes were chosen that were not included in the review: FAR, FTSST and FGA. FAR was considered important, given this patient’s limited axial mobility compared with age comparable individuals and given the known relationship between FAR and balance. 19 FTSST was chosen because of its ability to predict fall risk and as a proxy for lower extremity strength. FGA was used rather than the BBS. The latter would have been too easy for this patient and the FGA includes tasks such as walking backwards, head turns while walking, and ambulating on stairs, all of which were particularly relevant for this individual. Change in FAR was not reported in the systematic review, however it is noteworthy that the change in FAR (20°) was at the high end of improvement reported by Schenkman et al. 20 No comparison data were found for the other two outcomes. Can you apply the results of the systematic review to your own patients? Based on the PICO analysis, the results of the Cochrane review can be applied to patients such as Mr. Jennings. Clinicians should, however, consider a number of limitations to the data. First, the outcomes related to gait and balance but not to overall ability to function. This is important because improvements of gait do not necessarily lead to improvements in basic activities of daily living such as dressing and hygiene and to overall household activities such as cooking, cleaning, and managing laundry. Second, only short-term outcomes were examined. Yet PD is a progressive condition, hence shortterm benefits are important, but may be of true benefit only if the patient develops the skills and strategies for long-term adherence to appropriate exercise and activity.22 In this Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by Alan Daniel on November 29, 2014 6 regard, data are needed regarding the best strategies to assist patients to develop appropriate activity and long-term exercise habits. Additional limitations include: 1) no evidence was provided regarding specificity of intervention approaches; 2) evidence was insufficient to determine the most appropriate dose (intensity, frequency); 3) physiotherapy interventions were compared to no intervention or to placebo control ; 4) constraints of third-party payers may preclude a sufficient number of supervised sessions, hence consideration should be given to a combination of supervised and home programs to achieve the desired goals, although data are lacking regarding safety and the optimal balance between supervised and home components of a combined intervention. Further, evidence is not yet available to determine the best intervention strategies, based on subgroups of the disease (tremor predominate from PIGD form) or H&Y stages of PD. And finally, many patients have substantial co-morbid conditions that should be taken into account when designing the plan of care, both because of safety implications and because they can contribute to deficits of movement and function. Lastly, it is worth noting that across studies within the review, a high number of outcomes were used, and that these varied between studies. This is indicative of the lack of consistency that investigators are using to identify the impact of PD on health, function and quality of life. What can be advised based on the results of this systematic review? Findings from this systematic review demonstrate that people with PD achieve greater short-term improvements in gait and balance with physiotherapy intervention than do those individuals who receive placebo control or no physiotherapy intervention. Because PD is a progressive condition, short-term benefits are important, but may be of true benefit only if the patient develops the skills and strategies for long-term adherence to appropriate exercise and activity.25 Furthermore, these findings were obtained with a range of intervention approaches including general physical intervention, exercise, cueing, treadmill training, dance and martial arts. Hence clinicians can consider any of a range of intervention approaches when working with people, especially in early and mid-stages of PD and can take into account patient preferences. This finding is important given that people with PD likely need to develop long-term exercise habits to sustain benefits. Individuals are most likely to adhere to an exercise regimen if they are doing something they enjoy. Furthermore, some individuals may be more likely to develop sustained exercise habits if they can vary their approach. At the same time, clinicians are cautioned to consider the impairments that are most limiting to their patients when recommending which intervention approaches to use. Several large scale randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were published since this Cochrane review, comparing interventions to one another. 21,22,23,24 These studies illustrate specificity of training. For example, aerobic training improves cardiovascular function; resistance training improves muscle strength. This is important to consider, given that patients’ problems are multi-faceted and there is no single presentation of PD across patients. Additionally, considerable recent attention focuses on the possibility that Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by Alan Daniel on November 29, 2014 7 exercise of sufficient intensity may be neuroprotective, 25 suggesting that intensity may be critical. Lastly, attention also has turned to the importance of overall physical activity in addition to prescribed exercise for managing health of people with PD. 26 Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by Alan Daniel on November 29, 2014 8 Table 1. Key results from the 2012 Cochrane review The review included 33 randomized, controlled trials with a total of 1518 participants; H&Y 2.4 ; the number of participants in each trial ranged from 6-153. Search included trials published up to the end of December 2010. Risk of Bias: Of the reported upon criteria1 for risk of bias in the studies 44% were low, 46% unclear and 10% high. The most frequent areas of high risk were in randomization and withdrawals. General physical therapy (5 trials; 5 compared to no intervention, 0 to placebo control) Participants: n=197; mean age 65; 70% male; H&Y 2.3; 4 years since diagnosis Intervention: Approach: movement strategies, exercise, hands on treatment, education and advice for gait, balance transfers, posture and fitness; Duration: 5 weeks to 12 months; Session length not provided Exercise (12 trials; 10 compared to no intervention, 2 to placebo control) Participants: n=635; mean age 67; 63% male; H&Y 2.4; 6 years since diagnosis Intervention: Approach: strength, balance, walking, falls prevention, neuromuscular facilitation, resistance and aerobic training, education, and relaxation; Duration: 3-24 weeks; Session length: 30 min to 2 hrs Treadmill (7 trials; 5 compared to no intervention, 2 to placebo control) Participants: n =179; mean age 67; 68% male; H&Y 2.4; 5 years since diagnosis Intervention: Approach: walking on treadmill with adjustment of speed and incline; Duration: 4-8 weeks; Session length: 30-60 min Cueing (7 trials; 7 compared to no intervention, 0 to placebo control) Participants: n=303; mean age 68; 60% male; H&Y 2.5; 7 years since diagnosis Intervention: Approach: audio, visual, and sensory feedback (six applied to gait; one applied to sit to stand transfer); Duration: 2-8 weeks; Session length: 20 min to 2 hrs. Dance (2 trials; 2 compared to no intervention, 0 to placebo control) Participants: n=635; mean age 69; 64% male; H&Y 2.3; 7 years since diagnosis Intervention: Approach: Trained instructor for tango, waltz, or foxtrot; Duration: 12-13 weeks; Session length of 1 hr Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by Alan Daniel on November 29, 2014 9 Martial arts (4 trials; 4 compared to no intervention, 0 to placebo control) Participants: n=143; mean age 66; 72% male; H&Y 2.1; 7 years since diagnosis Intervention: Approach: Tai Chi (3); Quigong (1); Duration: 12-24 weeks; Session length: 1 hr A number of outcomes were reported in the various studies. Of those that were included, the following showed significant improvements with physiotherapy intervention as compared to placebo control or no intervention: Gait outcomes Two or six minute walk: mean difference = 16.4 m; 95% CI 1.90 to 30.90 Approach: exercise, dance , martial arts ; Trials= 4; Participants: n=172 Ten or 20 m-walk: mean difference = .40 sec; 95% CI 0.00 to 0.80 Approach: exercise, treadmill; Trials= 4; Participants: n=169 Velocity: mean difference = 0.05 m/sec; 95% CI 0.02 to 0.07 Approach: general physiotherapy, exercise, treadmill, cuing, dance , martial arts ; Trials= 11; Participants: n=529 Step length: mean difference = 3 cm; 95% CI 0.00 to 0.06 Approach: general physiotherapy ,exercise, treadmill, cuing; Trials= 3; Participants: n=239 Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by Alan Daniel on November 29, 2014 10 Clinician-rated disability Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) Total; mean difference = -4.46 points; 95% CI -7.16 to – 1.75 Approach: general physiotherapy, treadmill; Trials= 2; Participants: n=105 ADL: mean difference = -1.36 points; 95% CI -2.41 to -0.30 Approach: general physiotherapy, treadmill, dance; Trials= 4; Participants: n=157 Motor: mean difference = -4.09 points; 95% CI -5.59 to -2.59 Approach: general physiotherapy, exercise, treadmill, cuing, dance , martial arts ; Trials= 9; Participants: n=431 The following outcomes did not show any difference with physiotherapy intervention as compared to placebo control or no intervention: Gait outcomes Cadence (steps/min) : mean difference = -1.72 steps/min; CI -4.01 to 0.58 Approach: general physiotherapy , exercise, treadmill, cuing; Trials= 6; Participants: n=327 Stride length (m) : mean difference = 0.03 m; CI -2.78 to 7.57 Approach: general physiotherapy ,exercise, treadmill, cuing, dance, martial arts; Trials= 5; Participants: n=202 Freezing of Gait Questionnaire : mean difference = -1.19; CI -0.02 to 0.09 Approach: exercise , cuing, dance ; Trials= 3; Participants: n=246 Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by Alan Daniel on November 29, 2014 11 Functional Mobility and Balance Outcomes Activity of Balance Scale : mean difference = 2.4 points; CI -2.78 to 7.57 Approach: general physiotherapy , cuing; Trials= 3; Participants: n=66 Falls Efficacy Scale: mean difference = 2.4 points; CI 4.76 to 0.94 Approach: exercise , cuing; Trials= 4; Participants: n=353 Patient-rated quality of Life Parkinson’s Disease Questionarre-39( PDQ-39) : mean difference =-0.35 points; CI -2.66 to 1.96 Approach: general physiotherapy, exercise, dance, cuing, martial arts; Trials= 6; Participants: n=387 No trial reported data on adverse events 1 Not every study reported on every criterion. Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by Alan Daniel on November 29, 2014 12 Table 2. Outcomes from the intervention for Mr. Jennings Outcome measure Functional Reach Test Baseline 35.56 cm Discharge (8 weeks) 38.10 cm Change 2.54 cm Timed Up and Go Test Six Minute Walk Test Five Times Sit to Stand Test Functional Axial Rotation (degrees) Functional Gait Assessment (30 total) 10 sec 500 m 10 sec 100° 25 8 sec 650 m 10 sec 120° 27 -2.0 sec 150 m 0 20° 2 Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by Alan Daniel on November 29, 2014 13 REFERENCES 1. Samii A, Nutt JG, Ransom, BR. Parkinson’s disease. The Lancet 2004;363:1783-1793 2. Jankovic J. Parkinson’s disease: clinical features and diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2008; 79:368-376 3. Schenkman ML, Bowman JP, Gisbert RL, Butler RB. Clinical Neuroscience for Rehabilitation. Chapter 18. Pearson, Boston, MA, 2013 4. Dorsey ER, Constantinescu R, Thompson JP, et al. Projected number of people with Parkinson disease in the most populous nations, 2005 through 2030. Neurology 2007; 68:384-386 5. Hely MA, Morris JGL, Traficante R, Reid WG, O’Sullivan DJ, Williamson PM. The Sydney multicentre study of Parkinson’s disease: progression and mortality at 10 years. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;67:300-307. 6. Schenkman M. Current concepts in rehabilitation of people with Parkinson disease. In: McCulloch K, ed. Home Study Course, Alexandria, VA, American Physical Therapy Association, 2011 7. Jankovic J, McDermott M, Carter J, et al. Variable expression of Parkinson’s disease: a baseline analysis of the DATATOP cohort. Neurology. 1990;40:1529-1534. 8 Thengnatt MA, Jankovic J. Parkinson Disease Subtypes. JAMA Neurol. Available online: 10 FEB-2014 DOI information: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.6233 9. Goodwin VA, Richards SH, Taylor RS, Taylor AH, Campbell JL. The effectiveness of exercise interventions for people with Parkinson's disease: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Mov Disord 2008;23:631-40. 10. Keus SH, Bloem BR, Hendriks EJ, Bredero-Cohen AB, Munneke M. Evidence-based analysis of physical therapy in Parkinson's disease with recommendations for practice and research. Mov Disord 2007;22:451-60; quiz 600. 11. Kwakkel G, de Goede CJ, van Wegen EE. Impact of physical therapy for Parkinson's disease: a critical review of the literature. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 2007;13 Suppl 3:S478-87. 12. Morris ME, Martin CL, Schenkman M. Striding out with Parkinson disease: evidence based physical therapy for gait disorders. Phys Ther 2010;90:280-288. 13. Duncan RP, Earhart GM. Randomized controlled trial of community-based dancing to modify disease progression in Parkinson disease. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2012;26:132-43. 14. Tomlinson CL, Patel S, Meek C, Clarke CE, Stowe R, Shah L, et al. Physiotherapy versus placebo or no intervention in Parkinson's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;8:CD002817. 15. Wrisley DM, Kumar NA. Functional Gait Assessment: Concurrent , Discriminative, and Predictive Validity in Community Dwelling Adults. Phys Ther 2010; 90: 761-773 Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by Alan Daniel on November 29, 2014 14 16. Jenkinson C, Fitzpatrick R, Peto V, Greenhall R. The Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39): development and validation of a Parkinson’s disease summary index score. Age and Ageing, 1997; 26: 353-357. 17. Axial Schenkman M, Keysor J, Chandler J, et al. Axial Mobility Exercise Program: An Exercise Program to Improve Functional Ability. Fourth Edition, Durham, NC: Claude D Pepper Older Americans Independence Center, Duke University; 2004. 18. Schenkman M, Ellis T, Christiansen C, et al. Profile of Functional Limitations and Task Performance among People with Early and Mid-Stage Parkinson Disease. Phys Ther 2011;91:1339-1354. 19. Schenkman M, Morey M, Kuchibhatla M. Spinal flexibility and balance control among community-dwelling adults with and without Parkinson's disease. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M441-M445. 20. Schenkman M, Cutson TM, Kuchibhatla M, et al. A randomized controlled exercise trial in patients with Parkinson's disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:1207-1216. 21. Corcos DM, Robichaud JA, David FJ, et al. A two-year randomized controlled trial of progressive resistance exercise for Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord, 2013. 22. Li F, Harmer P, Fitzgerald K, et al. Tai chi and postural stability in patients with Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med, 2012;366:511-9. 23. Shulman LM, Katzel LI, Ivey FM, et al. Randomized clinical trial of 3 types of physical exercise for patients with Parkinson’s disease. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70(2):183-90 24. Schenkman M, Hall DA, Barón A, Schwartz RS, Mettler P, Kohrt WM Exercise for People in Early and Mid-Stages of Parkinson’s Disease: A 16-month Randomized Controlled Trial. Physical Therapy, 2012;92:1395-1410 25. Moore CG, Schenkman M, Kohrt WK, Delitto A, Hall DA Corcos D. Study in Parkinson Disease of Exercise (SPARX): Translating high-intensity exercise from animals to humans. Contemporary Clinical Trials. available online: 14-JUN-2013 DOI information: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.06.002 26. Ellis T, Schenkman M. The Benefits of Exercise and Physical Activity in Patients with Parkinson Disease. Focus on Parkinson's Disease, 2013 Amsterdam, In press Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by Alan Daniel on November 29, 2014 15 Physical Therapy Interventions for Parkinson Disease Robyn Gisbert and Margaret Schenkman PHYS THER. Published online November 25, 2014 doi: 10.2522/ptj.20130334 http://ptjournal.apta.org/subscriptions/ Subscription Information Permissions and Reprints http://ptjournal.apta.org/site/misc/terms.xhtml Information for Authors http://ptjournal.apta.org/site/misc/ifora.xhtml Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by Alan Daniel on November 29, 2014