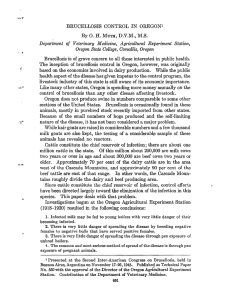

Transboundary and Emerging Diseases SHORT COMMUNICATION Isolation of Brucella abortus from a Dog and a Cat Confirms their Biological Role in Re-emergence and Dissemination of Bovine Brucellosis on Dairy Farms G. Wareth1,2, F. Melzer1, M. El-Diasty3, G. Schmoock1, E. Elbauomy4, N. Abdel-Hamid4, A. Sayour4 and H. Neubauer1 1 2 3 4 Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut, Federal Research Institute for Animal Health, Institute of Bacterial Infections and Zoonoses, Jena, Germany Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Benha University, Moshtohor, Egypt Animal Health Research Institute-Mansoura Provincial Laboratory, Mansoura, Egypt Animal Health Research Institute, Giza, Egypt Keywords: Brucella abortus; Bovine brucellosis; dogs; cats; re-emerging; spillover; Egypt Correspondence: G. Wareth. Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut, Federal Research Institute for Animal Health, Institute of Bacterial Infections and Zoonoses, Naumburger Str. 96a, 07743 Jena, Germany. Tel.: +4915779564050; Fax: +4936418042228; E-mail: gamalwareth@hotmail.com Summary Brucellosis is highly contagious bacterial zoonoses affecting a wide range of domesticated and wild animals. In this study, Brucella (B.) abortus bv 1 was identified in uterine discharge of apparently healthy bitch and queen with open pyometra housed on a cattle farm. This study highlights the role of dogs and cats as symptomatic carriers and reservoirs for Brucella. To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first report of feline infection with B. abortus bv 1 globally. These pet animals may contaminate the environment and infect both livestock and humans. Surveillance and control programmes of brucellosis have to include eradication of the disease in dogs, cats and companion animals. Received for publication February 16, 2016 doi:10.1111/tbed.12535 Background Brucellosis is an incapacitating zoonosis in humans and an economically disastrous disease in farm animals caused by Brucella spp. Bovine brucellosis is a worldwide-occurring zoonosis affecting cows, buffaloes and wildlife species. The causative agent is mainly Brucella (B.) abortus. Even though it has been eradicated from farm animals in many countries, in politically instable areas infection is re-emerging in livestock and consequently in humans (Corbel, 1997; Russo et al., 2009). In Egypt, brucellosis is prevalent nationwide in all farm animal species and in the environment. B. melitensis biovare (bv) 3 and less frequently B. abortus bv 1 are the predominate isolates which have been isolated from livestock, Nile catfish and from carrier hosts, for example rats (Wareth et al., 2014) and dogs (Hosein et al., 2001). The transmission of brucellae from wildlife to farm animals has been proven and spillover from livestock to wildlife has occurred (Godfroid, 2002; Truong et al., 2011, 2013). The role of pet animals on farms as reservoir has not been carefully studied in Egypt, yet. This study aimed to identify Brucella spp. in a seropositive bitch and a queen housed on an infected dairy cattle farm and to elucidate their potential role in maintaining the infection. Materials and Methods A dairy cattle farm with a total number of 500 Holstein cows and heifers located in Damietta governorate at the north costal region of Egypt had a history of brucellosis. The male animals in the farm were kept in a separate section for meat production. The farm suffered from brucellosis and the prevalence of brucellosis before control measures was around 7%. Following the current control programmes adopted by the General Organization for Veterinary Services (GOVS), all positive bovines were culled or slaughtered. Briefly, all cows, heifers and bulls were tested by rose bengal test (RBT) and serum © 2016 Blackwell Verlag GmbH • Transboundary and Emerging Diseases. 64 (2017) e27–e30 e27 First B. abortus from Dog and Cat in Egypt G. Wareth et al. agglutination test (SAT) followed by complement fixation test (CFT) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as confirmatory tests. Blood samples and samples of uterine discharge from dams, foetal tissues and stomach content from all aborted fetuses were cultured. B. abortus bv 1 was isolated from aborted cows. The farm was released from quarantine after three successive negative results in serology with 1-month intervals. Then, several cases of abortion were observed on the farm and brucellosis reemerged again. Two queens including one with open pyometra and one bitch that had aborted yet were housed on the farm and were in close contact with cattle and the automatic milking facility (Fig. 1). Blood samples collected from the bitch and the queen with open pyometra gave strong positive reactions using standard agglutination test. Samples of uterine discharge collected from the seropositive bitch and queen as well as from aborted cows were cultivated. Brucella identification and biotyping were performed based on colonial morphology, microscopic appearance, biochemical tests, CO2 requirement, H2S production, growth in the presence of the dyes thionine and fuchsine, agglutination with monospecific antisera and phage lysis (Alton et al., 1988). Following heat inactivation of bacteria at 80° for 2 h, DNA was extracted with the High Pure PCR template preparation kit (Roche Applied Sciences; Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The AMOS-PCR (B. abortus, B. melitensis, B. ovis and B. suis-PCR) was used (Bricker and Halling, 1994). Genotyping analysis of isolates using multiple locus of variable number tandem repeats analysis (MLVA-16) was performed (Le Fleche et al., 2006). Results and Discussion Fig. 1. Two cats drinking milk inside the automatic milking room of the infected farm. Bovine brucellosis, caused mainly by the bacterium B. abortus, is an economically important zoonosis due to abortions in cattle. It also affects other hosts including buffalo, bison and wildlife. In this study, one strain of Brucella was isolated from a bitch and a queen with open pyometra, respectively. The molecular and bacteriological examination identified the bacterium as B. abortus bv 1. As shown in Fig. 2, B. abortus isolates from the bitch and queen (ID: 15RB7429 and 15RB7430) have the same genotype as strains recovered from a cow of the same farm (ID: 15RB7432) and from cattle of the same region (ID: 14RB5309, 14RB5311and 14RB5312). Two isolates of Trueperella spp. were also recovered from the bitch and cat (data not shown). These opportunistic bacteria might have Fig. 2. Neighbour-joining analysis for the MLVA-16 profiles of Brucella abortus strains isolated from a bitch and a cat compared with isolates recovered from cattle in Egypt. Panel 1 includes eight minisatellite markers and Panel 2 is composed of eight microsatellite markers. The corresponding cells contain numbers of tandem repeats. e28 © 2016 Blackwell Verlag GmbH • Transboundary and Emerging Diseases. 64 (2017) e27–e30 First B. abortus from Dog and Cat in Egypt G. Wareth et al. been the cause of abortion and open pyometra seen in the bitch and queen, respectively (Ribeiro et al., 2015). A rapidly increasing population of housed and stray dogs and cats in Egypt has caused concern regarding transmission of zoonotic diseases. Dogs are the preliminary and natural host species for B. canis (Greene and Carmichael, 2013). B. canis is one of the most important bacterial infections causing abortion in the bitches, but it is uncommon in queens (Pretzer, 2008). Dogs can be infected also by B. suis, B. melitensis and B. abortus. The clinical signs of brucellosis in dogs range from asymptomatic course to abortion (Hollett, 2006; Ramamoorthy et al., 2011). Transmission of B. abortus from cattle to dogs has been suspected due to positive RBT (Cadmus et al., 2011) or Bruce-ladder PCR results (Truong et al., 2011). There has been an early attempt for isolation of B. abortus from dogs (Salem et al., 1974; Prior, 1976). On the other hand, cats can be experimentally infected with B. canis producing a transient bacteraemia. Infected cats do not shed brucellae and they are relatively resistant when challenged by the oral route (Tolari et al., 1982). DNA amplification of B. abortus in samples from wild felids kept at a zoo in Brazil was reported (Almeida et al., 2013). It is worth to mention that there is little information regarding feline brucellosis available in the literature at all. However, an outbreak of human brucellosis due to B. suis bv 5 was traced back to a pet cat in an urban setting (Repina et al., 1993). Isolation of B. abortus from the bitch and queen indicates the potential role of dogs and cats in the transmission and spillover of brucellosis to livestock and humans. Dogs and cats are not reported to be a major source of brucellosis for humans and farm animals, but they can play a significant role for the persistence of infection within a herd. Consequently, close contact with infected pets or with their secretions is a risk factor for diseases in livestock and humans. This study represents, to our knowledge, the first isolation and identification of B. abortus in dogs and cats in Egypt. Furthermore, this is the first report of feline infection with B. abortus. The bitch and queen in this study may have been infected by feeding of contaminated meat, aborted foetuses and/or drinking of contaminated milk. Most species of genus Brucella spp. are primarily associated with certain hosts. However, interspecies infections can also occur, particularly when they are kept in close contact. This study also highlights the gaps and drawbacks in the control and surveillance programmes of brucellosis which ignore the role of household and stray dogs and cats in brucellosis control. Our results suggested that B. abortus can be transferred to dogs and cats from cattle either directly or indirectly. B. abortus bv 1 is the second predominant Brucella spp. in cattle in Egypt. It can circulate in both housed or free-ranging dogs and cats representing a potential reservoir of infection for wildlife. These animals may also play a role in the spillover of brucellae from wildlife to farm animals. Control measures have to be implemented taking into account not only stray dogs and cats but also companion animals. Conclusion This study is the first to report the isolation and identification of B. abortus bv 1 from dogs in Egypt and from cats globally. We hypothesize that the bitch and queen served as intermediate reservoirs. The lack of awareness for the role of these animals in the infective cycle of cattle brucellosis may have caused the re-emergence of brucellosis in an otherwise well-kept dairy farm having biosecurity and biosafety measures in place. Conflict of interests This manuscript has not been simultaneously submitted for publication in another journal and been approved by all co-authors. The authors declare that they do not have any conflict of interest. References Almeida, A., C. Silva, L. Pitchenin, M. Dahroug, G. da Silva, V. Sousa, R. de Souza, L. Nakazato, and V. Dutra, 2013: Brucella abortus and Brucella canis in captive wild felids in Brazil. Int. Zoo Yearb. 47, 204–207. Alton, G. G., L. M. Jones, R. D. Angus, and J. M. Verger, 1988: Techniques for the Brucellosis Laboratory, pp. 17–62. Instituttional de la Recherche Agronomique, Paris. Bricker, B. J., and S. M. Halling, 1994: Differentiation of Brucella abortus bv. 1, 2, and 4, Brucella melitensis, Brucella ovis, and Brucella suis bv. 1 by PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32, 2660–2666. Cadmus, S. I., H. K. Adesokan, O. O. Ajala, W. O. Odetokun, L. L. Perrett, and J. A. Stack, 2011: Seroprevalence of Brucella abortus and B. canis in household dogs in southwestern Nigeria: a preliminary report. J. S. Afr. Vet. Assoc. 82, 56–57. Corbel, M. J., 1997: Brucellosis: an overview. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 3, 213–221. Godfroid, J., 2002: Brucellosis in wildlife. Rev. Sci. Tech. 21, 277– 286. Greene, C. E., and L. E. Carmichael, 2013: Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat, 3rd edn. Available at http://www.vet.unicen. edu.ar/html/Areas/Documentos/Enfermedades Infecciosas/ 2013/Libros/Greene – Infectious diseases to the Dog and Cat 3rd Ed/40 Canine Brucellosis.pdf (accessed January 15, 2015). Hollett, R. B., 2006: Canine brucellosis: outbreaks and compliance. Theriogenology 66, 575–587. Hosein, H., Y. Sohair, M. Enany, and M. Gabal, 2001: The role of some Brucella carriers (stray dogs and cats) in maintenance of Brucella infection. Beni-Suef Vet. Med. J. XI, 521–529. © 2016 Blackwell Verlag GmbH • Transboundary and Emerging Diseases. 64 (2017) e27–e30 e29 First B. abortus from Dog and Cat in Egypt G. Wareth et al. Le Fleche, P., I. Jacques, M. Grayon, S. Al Dahouk, P. Bouchon, F. Denoeud, K. Nockler, H. Neubauer, L. A. Guilloteau, and G. Vergnaud, 2006: Evaluation and selection of tandem repeat loci for a Brucella MLVA typing assay. BMC Microbiol. 6, 9. Pretzer, S. D., 2008: Bacterial and protozoal causes of pregnancy loss in the bitch and queen. Theriogenology 70, 320–326. Prior, M. G., 1976: Isolation of Brucella abortus from two dogs in contact with bovine brucellosis. Can. J. Comp. Med. 40, 117–118. Ramamoorthy, S., M. Woldemeskel, A. Ligett, R. Snider, R. Cobb, and S. Rajeev, 2011: Brucella suis infection in dogs, Georgia, USA. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 17, 2386–2387. Repina, L. P., A. I. Nikulina, and I. A. Kosilov, 1993: [A case of human infection with brucellosis from a cat]. Zh. Mikrobiol. Epidemiol. Immunobiol. 4, 66–68. Ribeiro, M. G., R. M. Risseti, C. A. Bolanos, K. A. Caffaro, A. C. de Morais, G. H. Lara, T. O. Zamprogna, A. C. Paes, F. J. Listoni, and M. M. Franco, 2015: Trueperella pyogenes multispecies infections in domestic animals: a retrospective study of 144 cases (2002 to 2012). Vet. Q. 35, 82–87. e30 Russo, G., P. Pasquali, R. Nenova, T. Alexandrov, S. Ralchev, V. Vullo, G. Rezza, and T. Kantardjiev, 2009: Reemergence of human and animal brucellosis, bulgaria. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 15, 314–316. Salem, A., O. Hamed, and A. Abdel-Karim, 1974: Studies on some Brucella carriers in Egypt. Assiut Vet. Med. J. 1, 180–187. Tolari, F., R. Farina, M. Arispici, and R. Orsi, 1982: Brucellosis in the cat. Experimental infection with Brucella canis. Ann. Sclavo 24, 577–585. Truong, L. Q., J. T. Kim, B. I. Yoon, M. Her, S. C. Jung, and T. W. Hahn, 2011: Epidemiological survey for Brucella in wildlife and stray dogs, a cat and rodents captured on farms. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 73, 1597–1601. Truong, Q. L., T. W. Seo, B. I. Yoon, H. C. Kim, J. H. Han, and T. W. Hahn, 2013: Prevalence of swine viral and bacterial pathogens in rodents and stray cats captured around pig farms in Korea. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 75, 1647–1650. Wareth, G., A. Hikal, M. Refai, F. Melzer, U. Roesler, and H. Neubauer, 2014: Animal brucellosis in Egypt. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries 8, 1365–1373. © 2016 Blackwell Verlag GmbH • Transboundary and Emerging Diseases. 64 (2017) e27–e30