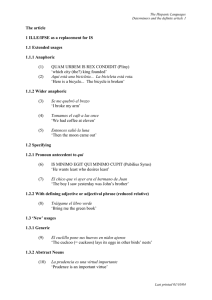

REVISITING SUBJECTIFICATION AND INTERSUBJECTIFICATION Elizabeth Closs Traugott

Anuncio